Analysis of the impacts of socioeconomic factors on hiring an external labor force in tilapia farming in Southern Togo

Kodjo N’Souvi, Chen Sun,*, Aklesso Egendewe-Mondzozo, Koffi Kfui Thkh,Bortey Nketi Ali-Doku

aCollege of Economics and Management, Shanghai Ocean University, 201306, Shanghai, China

bFacult′e des Sciences Economiques et de Gestion (FaSEG), Universit′e de Lom′e, P.O. Box 1515, Lom′e, Togo

cFacult′e des Sciences Economiques, Sociales et de Gestion, Universit′e de Reims Champagne-Ardenne, 51096, Reims Cedex, France

ABSTRACT

Keywords:

Tilapia

Economic returns

Hired labor force

Logit model

Return on investment

Southern Togo

1.Introduction

In many countries, humans have been exploiting water resources through fishing and aquaculture to meet their needs, mainly for food.More than 4000 years ago, the first aquaculture trial began in Africa,especially in Egypt, with the production of tilapia (FAO, 2017). With the development of fish breeding technology, tilapia has been artificially cultivated in about 85 countries around the world (FAO, 2008). Among the farmed tilapia species, Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) is one of the most popular species. The global production of tilapia was 4,200,000 tons in 2016 (FAO, 2018).

The growing importance of the demand and consumption of fish products by the population in the modern world creates a large gap between the demand and the production of fish, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. Such a situation lets a little doubt on the considerable potential for the development of tilapia farming in this area (Atanda &Fagbenro, 2017; El-Sayed, 2017; Frimpong & Anane-Taabeah, 2017;Hyuha et al., 2017; Ngugi et al., 2017). In Togo, the country highly imports fish from other countries. Natural resources such as rivers, lakes,sea and lagoons exist and local climatic conditions are favorable for aquaculture. The country has enormous potential for the development of fish farming that can reduce its external dependence on animal protein and generate employment opportunities for the rural population.Although the local and international organizations have taken the proper actions, the situation of fish farming remained unchanged. The annual consumption of animal protein in Togo is 13 kg per capita (DPA,2011), which is less than the average value in Sub-Saharan Africa (16 kg per capita) (WFC, 2004).

The demand for fish in Togo is keeping pace with the growth of the population. In 2010, the demand for fish was 47,672 tons in Togo. In the same year, domestic fish production was 27,635 tons, while the country imported 20,037 tons of fish from other countries (FAO, 2012). The annual piscatorial production is about 25,000 tons in Togo (DPA, 2011).Such a production is far from covering the national demand for fish,which represents almost 40% of animal protein consumption (Brummett et al., 2008). The country’s demand for fish is mainly covered by imported fish from other African and Asian countries. The development of fish farming can solve the problem. Therefore, the assessment of socio-economic factors is essential to increase the fish production of the country.

Very few reports have been studied on the issue of tilapia farming in Togo (Adjanke et al., 2016; Agbokousse et al., 2016). The previous studies had been focused on physico-chemical parameters for the growth of tilapia and its biological aspects. The parameters for the culture of this fish species are important from the socioeconomic point of view.Nevertheless, no study has been reported about the socioeconomic aspects of the culture of fish in Togo. Understanding of socioeconomic factors, which contribute significantly to the use of external labor force in tilapia farming in Togo, is very important in terms of economic development. Increasing the number of tilapia farms can locally increase the demand for the labor force in this sector. However, given the role of this fish in the food of Togolese and its contribution to the national economy, it is crucial to figure out the socio-economic factors that influence the Nile tilapia production. The differences in the profitability and socio-economic aspects must be involved in the decision of the tilapia farmer to adapt to the different farming systems (monoculture or polyculture), the integration of tilapia farming with other agricultural practices or the decision to hire an employee.

Therefore, this study aimed to analyze the socioeconomic factors to in fluence tilapia farmers’ decision to recruit external labor force in their farms and investigate the net farm income and the return on investment from tilapia farming in Southern Togo. This is the first report to examine the socioeconomic factors that significantly contribute to employment opportunities in tilapia farms in Southern Togo.

1.1.Empirical literature

Many people around the world find a source of income and livelihood in the fisheries and aquaculture sectors. Recent statistics indicate that people engaged in capture fisheries and aquaculture in 2016 were 40.3 and 19.3 million, respectively (FAO, 2018). The proportion of people employed in fish farming increased from 17% in 1990 to 32% in 2016. Historically, the fish farming sector had mostly used family labor.Since fish farming has been practiced commercially, either family or hired laborer, or both are used, which provide employment opportunities. The use of these distinct categories of the productive laborer in the fish farms may cause changes in socioeconomic characteristics according to regions/areas.

The study of the economic impact of the cat fish farming industry in Mississippi State (Hanson et al., 2004) revealed that 6670 jobs were directly generated through cat fish production and processing. Many cat fish farm activities in Mississippi were seasonal in nature. In the earlier 2000s, cat fish farmers in their study areas employed many seasonal laborers from Mexico and other Latin American countries because their activities required full-time employment every year from the spring to fall. The increased number of these seasonally hired workers is beneficial to both farmers and hired workers. The cat fish industry in Mississippi provided job opportunities for young people to develop their skills and pursue their careers so that they can be engineers, mechanics,skilled food scientists, technicians, trained marketers, salesman, data processors, accountants and truck drivers.

Engle (2007) studied on cat fish farming budgets in Arkansas (USA)and found that the productive labor force was provided either by family members or hired workers. According to the findings, the successful recruitment of the wage workers typically depends on the considerable size of fish farms. Such workers can be full-time workers for a certain period or part-time laborers over the whole year. In addition, farmers sometimes hire managers and seasonal helpers for other tasks.

In China, the development of tilapia farming helped local Chinese farmers to change their livelihood. There are more than 300,000 people working in tilapia farms in China. Additionally, the owners of the fish farms recruit many other people in feed and nursery (Hanson et al.,2011). Tilapia processing often absorbs extra labor and processing in major producing areas has strengthened local economic prosperity.About 12,000 farmers in Uganda work in tilapia farms, one of the important species farmed in the country. Tilapia farming provides employment opportunities. Local people gainfully employed in tilapia farms ranged from hired laborers to the pond owners (MAAIF, 2012).

Paul and Vogl (2012) studied the characteristics of performing Shrimp farming in Bangladesh. They had found most of the farmers hire wage laborers to construct ponds for shrimp and finfish cultivation in Southwest Bangladesh. They pointed out that more than four fish farmers per production cycle, on average, mostly hire laborers for heavy works, such as ponds construction and their maintenance. In addition,the larger the farm/pond area, the larger is the fish farmer’s likelihood of hiring wageworkers. Likewise, almost 100% of the farmers in Myanmar employ their own family laborer and hired casual laborer regardless of crops and farm size. However, fish farms annually generate, on average, employment for both family members, hired casual workers and hired long-term workers four times higher than that one in crop farms (Belton et al., 2017).

According to IBGE (2017), p. 1% of 3.5 million jobs that the entire fish farming value chain has created in Brazil comes from tilapia farming. Employment opportunities locally provided by tilapia farming have helped to mitigate the issues of rural emigration and rural emptiness. Tilapia farming ideally has a multiplier effect on the employment generation by entailing on average, 1 worker day to process 120 kg of tilapia, 1 worker month to produce 20 tons of tilapia feed, and 1 worker month to produce 100,000 fingerlings (Barroso et al., 2019). Tilapia farming and other industries on the tilapia value chain efficiently generate decent jobs and reliably provide livelihood opportunities to the rural population. The wages paid to workers on the tilapia value chain are higher than the national minimum wage. Many tilapia farms in the south and southeast offer other extra benefits such as salary progression and year-end bonuses to their productive employees. The tilapia processing industry has created a large labor demand resulting in more competition and more skills for the workers and then a shortage of skilled laborers in the sector.

A recent study by Roriz et al. (2017) demonstrated that more than half of tilapia farmers in Brazil hired laborers in their farms and the remaining staff consisted of family members. Their findings revealed that farms with up to three workers were predominant (81.3%). Among the farms with more than three workers, 67% of the laborer were hired.The characteristics that enable tilapia farmers in their decision to hire external labor force may be different from one farmer to another.

According to the literature reviews, the following hypotheses are formulated to finalize the objective of this study: a) we assume that the higher the tilapia farmer’s profit, the greater his hiring capacity of an external labor force. b) The more the diversity of his activity, the larger the fish farmer’s likelihood of hiring wageworkers. c). The higher the tilapia farmer education level, the greater his likelihood of employing an external labor force in his tilapia farm.

2.Materials and methods

2.1.Study area and data collection

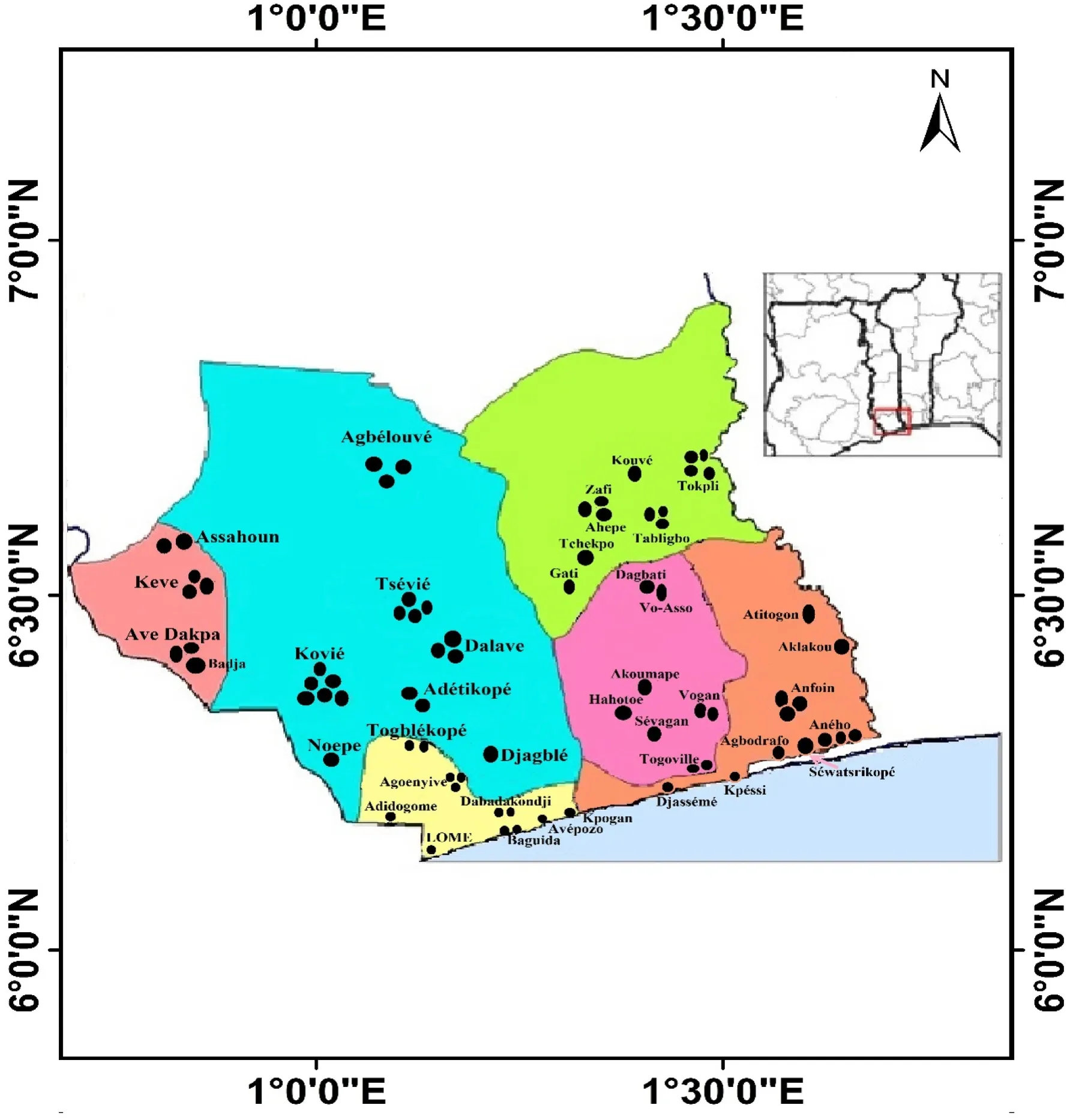

This present study was conducted on tilapia farms in Southern Togo(Fig. 1). The number of aquaculture centers is limited in the country. For instance, in 2011, fishponds were mainly abundant (92%) in the Maritime and Plateaux regions, while the water reservoirs were mostly from the northern part of the country (UEMOA, 2013). In this study, the Maritime region of Southern Togo was selected. We collected the primary data from 75 randomly selected fish farmers in Southern Togo.Structured interviews were carried out using a questionnaire-style interview to analyze the parameters for tilapia farming. The questionnaire comprised of a set of questions related to the socioeconomic status of tilapia farmers. It included a printed set of questions, either open-ended or closed-ended. The respondents were required to answer the questions based on their knowledge and experience in fish farming.A systematic random sampling technique was implemented. The interviews were conducted face-to-face in fish farms.

Fig. 1.Map of Southern Togo showing the study area 2020/4/9.

2.2.Theoretical framework and econometric model

2.2.1.The model

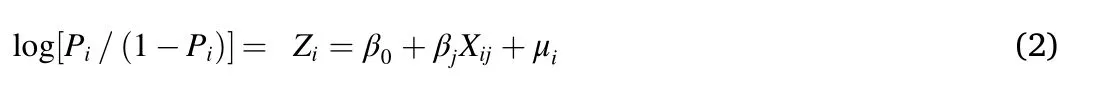

A qualitative choice model, a Logit model was used to estimate the effects of different socioeconomic factors on the probability that a tilapia farmer decides to recruit the employee. The methodology of our study is based on the empirical model used by Musaba and Namukwambi(2011). The equation of the Logit model is given as follows:

where, e represents the base of the natural logarithm, Zis an index determined by an independent variable (Xi) and Pi is the probability of making a certain decision by tilapia farmer. The equation (2) is estimated as follows:

In this equation, the expression on the left side denotes the logarithm of the probability of the representative individual’s decision to hire an external labor force in his tilapia farm. μis the error term. The βparameter of the Logit model was estimated by the Logistic estimation approach.

The coefficients of the Logit model do not provide any sign and significance of the coefficients of the explanatory variables. In this study,the change in the probability of hiring an external labor force with respect to a unit change in the explanatory variable was estimated as follows:

where, Pindicates the probability of hiring an external labor force in the farm by tilapia farmer at the mean value and k is the coefficient of the kth variable.

2.2.2.Empirical specification of the model

The dependent variable is binary with an assigned value of 1 when the tilapia farmer employs an external labor force and equal to 0 if he employs family labor force in his farm. The logistic model was used to perceive the effect of socioeconomic variables on the dependent variable, which is given as follows:

where, the dependent variable is a discrete variable defined as the value 1 when the tilapia farmer employs non-family laborers and equal to 0 otherwise. ε is the error term of the model, where Z =Xand the explanatory variables are as defined in Table 1. The decision of the tilapia farmer to employ a non-family laborer was hypothesized to depend on a specific number of socio-economic factors, such as profit,technical assistance, diversification of source of income, education level of farmer, gender, farming system, pond type, polyculture of the species,area of the water and farming experience.

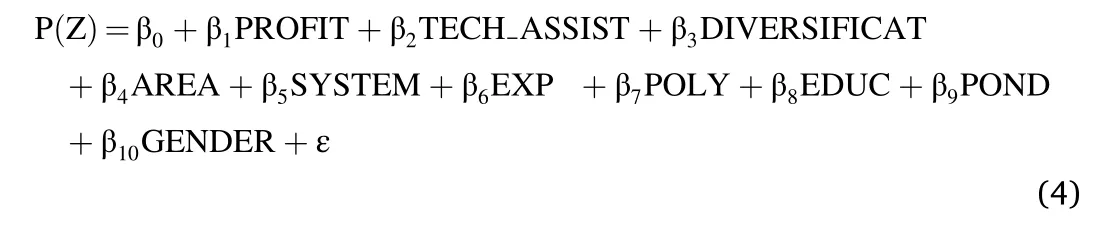

Table 1Socioeconomic characteristics of the tilapia farmers.

2.2.3.Economic returns technique

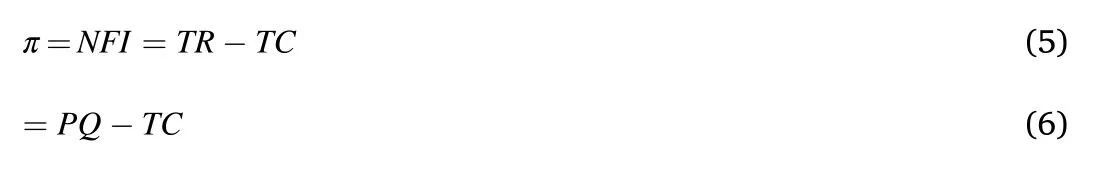

The economic return approach consists of comparing revenue to cost supported by the farmer using indicators, such as net farm income (NFI),gross margin and return on investment (ROI). NFI analysis compares total revenue to the total cost. The equation is given as follows:

where, NFI =net farm income, TR =total revenue, TC =total cost, P =tilapia unit price per Kg, and Q =total weight of tilapia in kg. For data processing, the collected data were used to make a list of the different variables for the empirical model. Epidata 3.1, Excel 2016 and Stata 16 software were used to analyze the data.

3.Results

3.1.Socioeconomic features of surveyed tilapia farmers in Southern Togo

Table 1 shows the socioeconomic characteristics of tilapia farmers in the study area. The age of the majority (65.34%) of fish farmers was 36-54 years. The average age is 40.68 years. The average size of fish farms was 0.43 ha (4300 m), while the farm size of the majority (48%)of fish farmers was between 0.1 and 0.4 ha. Furthermore, tilapia was the major species (42.67%) farmed in the monoculture system. However,most of the farmers (46.66%) preferred polyculture system i.e. tilapia integrated with other species (cat fish, shrimp and carp). Only 40% of farmers were full-time farmers. Apart from fish farming, most of the local farmers (60%) had diverse economic activities. On the other hand,the extensive culture system dominates (41%), followed by semiintensive (31%), and intensive systems (28%) respectively. In addition to family laborers used in the farms (not all of them), 44% of the farmers in the study area hired an external labor force.

The farmers had average 11 years of farming experience and almost one-third of the farmers received technical assistance from either government or NGOs. Tilapia farming was practiced in a mostly concrete pond and earthen pond, accounting for 98.67% in tanks and water reservoirs and 1.33% of the farmers use cages. The level of education of the farmers varied from 2 to 17 years (average 7.92 years). With respect to gender, the majority of the tilapia farmers in Southern Togo were men(69%).

The extensive fish culture systems are characterized by low stocking,absence of additional feed and pond fertilization to stimulate the growth of natural food in the water. Ponds used for extensive culture system are usually large and are generally earthen ponds. Production is generally lower than that of semi-intensive and intensive culture. Semi-intensive and intensive culture systems require more use of inputs, such as feeds, fertilizers, pesticides and good water management. Farmers feed the fish at least 3 times a day. Intensive and semi-intensive tilapia culture systems in Southern Togo are labor-intensive.

Despite the increasing role of women in tilapia farming in Southern Togo, women were inferior to men in terms of the ownership of the tilapia farms (Table 1). The majority of the women in tilapia farming work in post-harvest activities such as drying, smoking, processing and sale of aquatic products.

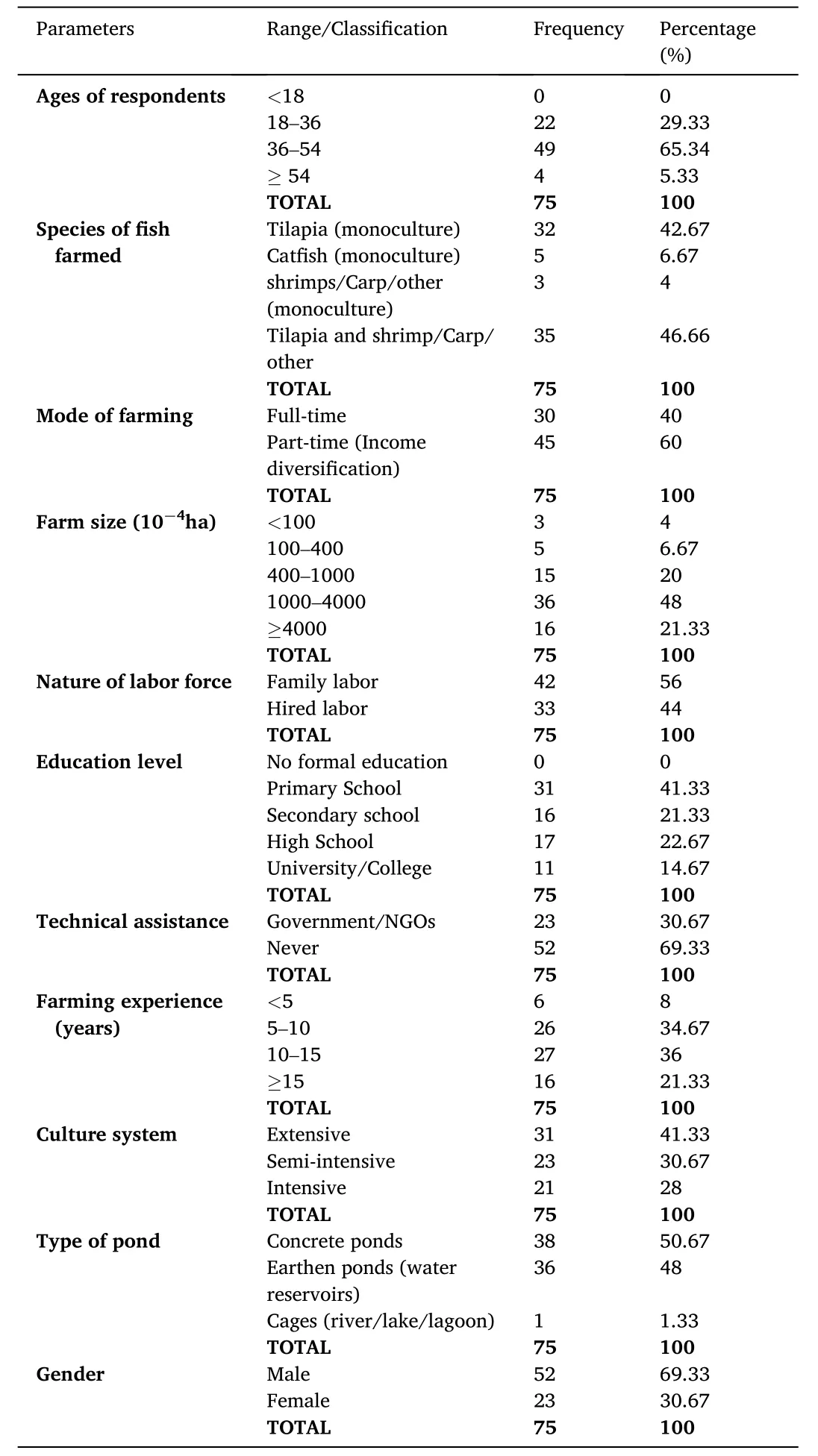

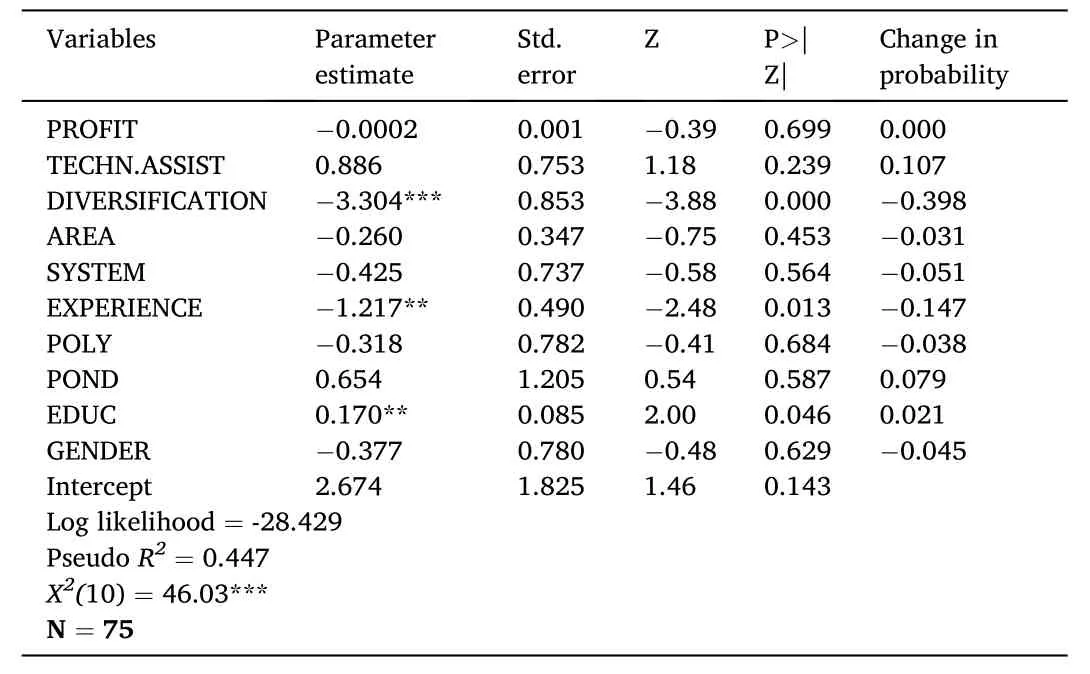

3.2.Logistic regression analysis

The results of the econometric model of our equation (4) are shown in Table 2. The Likelihood Chi-squared test ratio with a value of 46.03 (P value =0.000) showed that the Logistic model fitted to the data ascompared to the null model with no independent variable. The F-statistic was statistically significant, implying that all the explanatory variables are related to the tilapia farmer’s decision and ability to hire an external labor force. The coefficient of determination, pseudoR

indicates that 44.7% of the tilapia farmers decided to employ an external labor force by the changes in the explanatory variables.

Table 2The results for tilapia farmer’s decision to hire an external labor force.

Technical assistance, experience, polyculture and education are designated as TECHN.ASSIST, EXP, POLY and EDUC, respectively.

The logistic regression showed that three coefficients were statistically significant and the test of their significance proved it. The results showed that the probability of the tilapia farmer in Southern Togo to hire an external labor force was significantly and negatively in fluenced by “Diversification” and “Farming experience”, and positively in fluenced by “Education”.

The negative sign for the “diversification’’ implies that tilapia farmers who have no other source of income were, on average, more likely able to hire external labor force promptly. Apart from tilapia farming, a farmer who diversifies his sources of income would be 40% less likely to hire an external labor force in his farm. Our results revealed that farmers who have less experience in tilapia farming were more likely able to hire external labor force. For each year in tilapia farming experience, 14.7% of the farmers were less likely to employ an external labor force on his farm. Additionally, the findings indicated that farmers who have a high level of education were more likely able to hire external labor force. Moreover, for each additional year of education, there were 2% more likely the tilapia farmer employed an external labor force. In a word, farmers who did not diversify tilapia farming activities i.e. have no other activities for income generation, less experience in tilapia farming and high level of education were more likely able to hire external labor force.

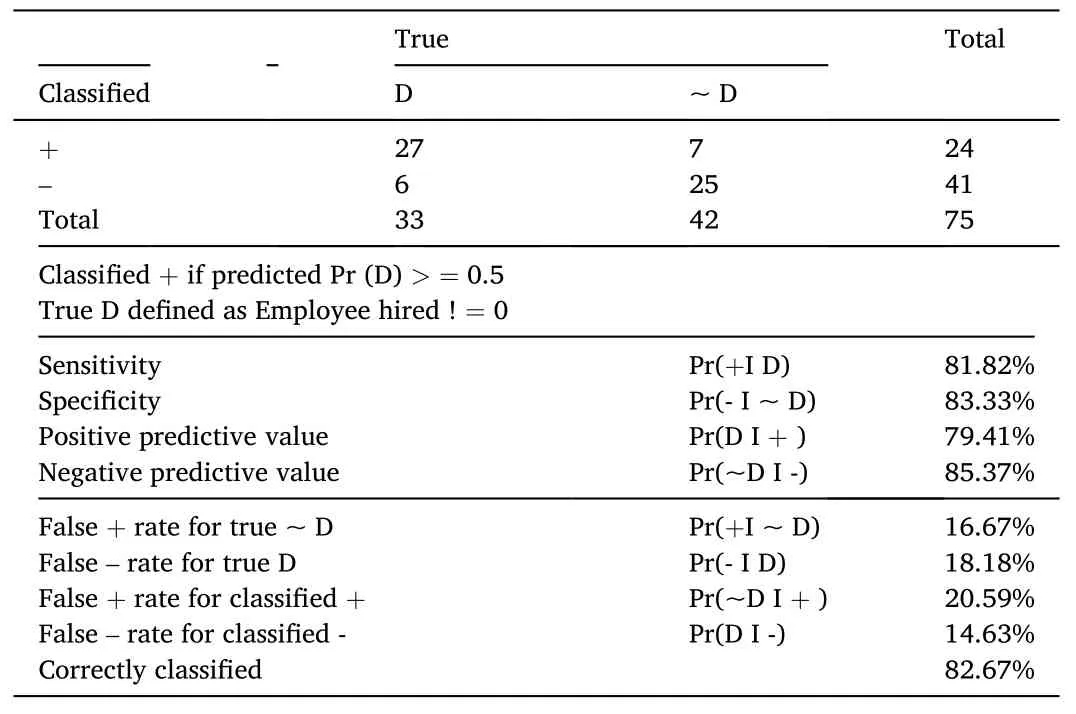

The test of goodness of thefit (Table 3) showed that our model correctly predicted 82.67% of the estimation.

Table 3Goodness of the fit of Logit estimation for employee-hired.

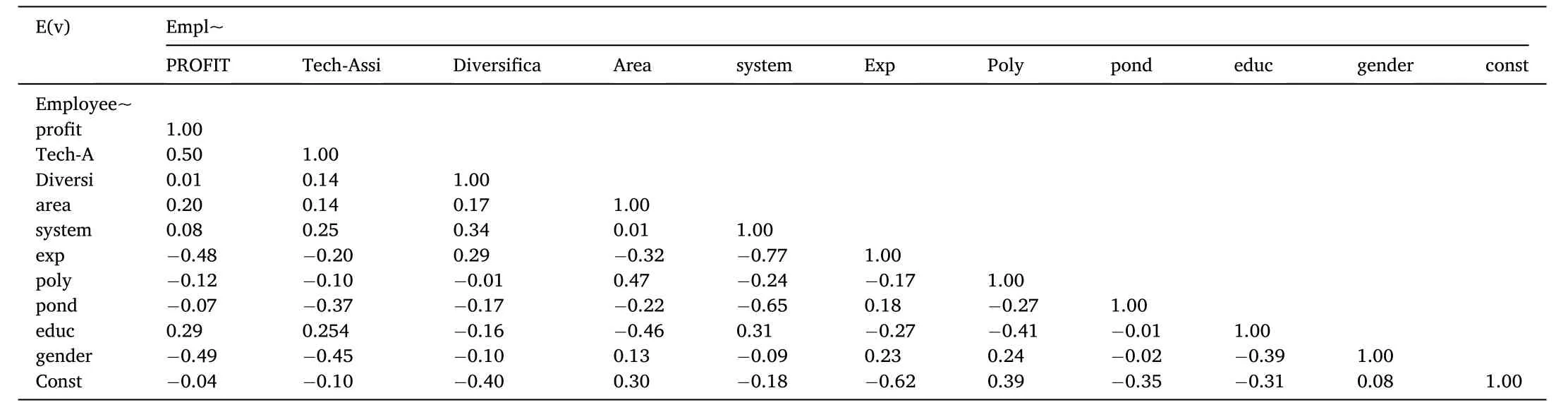

In addition, correlation analysis revealed that the explanatory variables were not significantly correlated, indicating that there is the absence of multicollinearity in the regression model (Table 4).

Table 4Correlation matrix of coefficients of Logistic model.

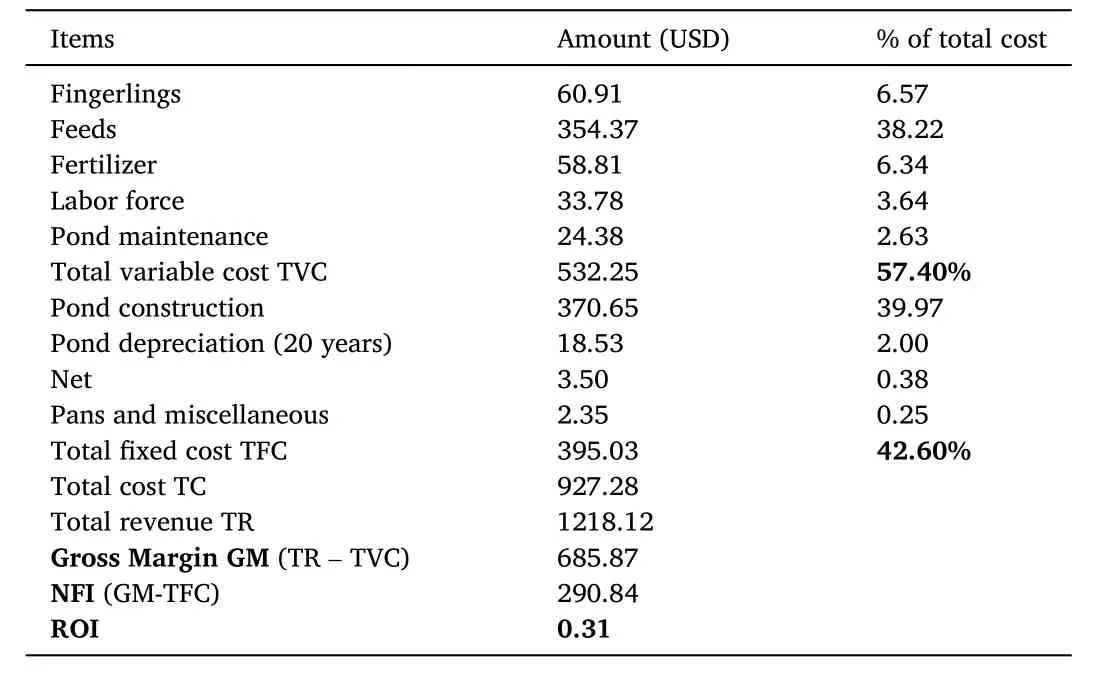

3.3.Analysis of economic returns

To determine the net farm income level, we calculated the costs and revenue of tilapia farmers. Data on the inputs, and the outputs produced by the farmers were used to assess the profitability of tilapia farming.The overall cost structure of an average tilapia farm is presented in Table 5. The results revealed that the pond construction accounted for the largest proportion (39.97%) of the total cost of tilapia production,followed by feed cost (38.22%) and fingerlings (6.57%). Organic fertilizer, labor force and pond maintenance accounted for 6.34, 3.64 and2.63%, respectively of the total production cost. According to the results, the construction of the ponds, the cost of feeds and the purchase of the fingerlings were the main operating costs of the farmers.

Table 5Cost structure of an average tilapia farm in Southern Togo.

An average of tilapia farmers generated gross revenue of USD 1218.12 with a gross margin of USD 685.87 and a net farm income of USD 290.84 per production cycle obtained between 4 and 6 months. The rate of ROI of 0.31 implied that a return of USD 0.31 was obtained during the production period in the study area for every single dollar invested in tilapia farming by the farmers.

4.Discussion

Tilapia farming is economically profitable in Southern Togo, and the socioeconomic factors, such as economic diversification, farming experience and the level of education significantly affect the farmers’ decision to hire an external labor force. Economic diversification is related to the development of integrated tilapia and crop farming operations and other income generation activities, which significantly affect the farmers’ key decision of hiring an external labor force. However, there is limited evidence about the impact of economic diversification on tilapia farmer’s decision to hire an external labor force. If the farmer has more income-generating activities, he spends less time and resources for tilapia farming and hires less labor force for his farm.

The possibility of hiring a labor force in fish farms was significantly affected by tilapia farming experience. In contrast, Amankwah et al.(2016) have reported that fish farming experience is positively correlated with the adaptation of aquaculture technologies. The adaptation of aquaculture technologies is positively associated with the labor demand in fish farming (Obiero et al., 2019). From this viewpoint, it can also be said that farming experience affects the labor demand in fish farming.The experience in tilapia farming significantly affects labor demand,which means that young farmers with less experience are more likely to recruit an external labor force for their farms in Southern Togo.

Education is a key element for better job opportunities. Generally,higher educated farmers can access information on production processes and analyze new information. Relevant components of innovative behavior are farmers’ ability to generate and implement new ideas and the involvement of the workforce in the adaptation process. Worker’s involvement is a critical factor within the definition of farmers’ innovative behavior (Cofre- Bravo et al., 2018). According to Ngoc et al.(2016), educational qualification is significantly associated with the adaptation to fish farming technology. The adaptation of such technology requires an additional use of labor force with engineers, mechanics,skilled food scientists and technicians, trained marketers and salesmen,data processors and truck drivers. Recently, Rahman and Barmon (2019)noted that the factors, such as output price, real wage, education leveland experience in fish farming affect the decision of hiring labor force in Bangladesh. However, the impacts of socio-economic factors on hired labor demand varied according to gender. In general, the likelihood of hiring both male and female laborers increases with the cultivated area in the fish farm, but the likelihood of hiring male laborers is lower than that of the female. However, educated fish farmers hire more female laborers along with male laborers because the wage of the female laborer is sometimes lower than that of the male in some countries.Besides, the additional year of education increases tilapia farmers’probability of hiring an external labor force, which indicates the positive effect of modern education on tilapia farmers’ decision of using hired labor force.

The other factors such as profit and technical assistance were not statistically significant. The reason is that the majority (nearly 70%) of fish farmers in the study area raise tilapia for a commercial purpose, but the variable ’’Profit’’ is not significantly related to the probability of hiring an external labor force. However, the relatively small sample size for this study may affect the results.

In case of economic returns, we found the value of 0.31 for the ROI in our study, which is similar to the results of Kassali et al. (2011), who found that aquaculture production was profitable with a rate of return of 61%. Ideba et al. (2013) analyzed the factors affecting fish farming and observed that fish farming in Calabar was profitable as the majority of the farmers made a gross margin of ?400,000-700,000 the equivalent of USD,1101.11- 1926.94 per annum. Tunde et al. (2015) have shown that fish farming is profitable in Oyo State, Nigeria, and ROI was 0.88.Similarly, Mkong et al. (2018) assessed the main determinants of profitability of fish breeding in Cameroon and reported a mean net profit of 1,896,443 FCFA (USD 3207.08) per production cycle of 4 months and profitability of fish farmers was in fluenced by the costs of feed,fingerlings and labor force.

5.Conclusion

This study analyzed the socioeconomic factors, which affect tilapia farmers’ decision to hire external labor force and assessed the economic returns of tilapia farming in Southern Togo.

The econometric results of the Logit model showed that the farmers who did not diversify their source of income and had less experience in tilapia farming and high level of education, were more likely able to hire external labor force. Also, the results of economic returns revealed that tilapia farming in Southern Togo is profitable, and it can generate employment opportunities by enabling the farmers to recruit external labor force.

We recommend that females need to be encouraged to participate in tilapia farming in Southern Togo since tilapia farming is dominated mainly by males in the study area. As the tilapia farmers’ decision to hire an external labor force is negatively affected by economic diversification, it is better not to diversify their economic activities. Supplementary financial investment being a necessary condition to ensure economic diversification. However, only one-third of the tilapia farmers in Southern Togo receive technical and financial assistance. By diversifying their economic activities, they allocate a part of their limiting resources to other activities, thereby lowering the likelihood of hiring an external labor force in tilapia farms. To solve the problem, local authorities can call on countries with proven aquaculture expertise and experience (e.g.China, Indonesia, Egypt) to provide technical assistance to fish farmers.Increased financial assistance from FAO for aquaculture development will also be of great importance. Finally, the government must take necessary steps to organize training or re-training workshops for tilapia farmers to increase their knowledge of pond management, which will progressively increase the likelihood of the local farmers and the employment opportunities.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Kodjo N’Souvi: Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing -original draft, Data curation, Funding acquisition. Chen Sun: Investigation, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing - review &editing, Writing - original draft, Data curation, Supervision. Aklesso Egbendewe-Mondzozo: Investigation, Conceptualization, Supervision.Koffi Kafui Tchakah: Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. Bortey Nketia Alabi-Doku: Formal analysis, Writing - original draft.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to in fluence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the tilapia farmers who participated in the questionnaire.

Aquaculture and Fisheries2021年2期

Aquaculture and Fisheries2021年2期

- Aquaculture and Fisheries的其它文章

- Editorial: Global fish passage issues

- Using Bayesian Bio-economic model to evaluate the management strategies of Ommastrephes bartramii in the Northwest Pacific Ocean

- Endosymbiotic pathogen-inhibitory gut bacteria in three Indian Major Carps under polyculture system: A step toward making a probiotics consortium

- Expression of multi-domain type III antifreeze proteins from the Antarctic eelpout (Lycodichths dearborni) in transgenic tobacco plants improves cold resistance

- A chromosome-level genome assembly of the red drum, Sciaenops ocellatus

- Loss of scleraxis leads to distinct reduction of mineralized intermuscular bone in zebra fish