Frailty significantly impairs the short term prognosis in elderly patients with heart failure

Ali Deniz, Caglar Ozmen, Ertugrul Bayram, Gulsah Seydaoglu, Ayhan Usal

1Cukurova University, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Cardiology, Adana, Turkey

2Adana Numune Education and Research Hospital, Department of Medical Oncology, Adana, Turkey

3Cukurova University Faculty of Medicine, Department of Biostatistics, Adana, Turkey

Abstract Background Frailty is a condition of elderly characterized by increased vulnerability to stressful events with high risk of adverse outcomes. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the association between frailty and adverse outcomes including death and hospitalization due to heart failure in elderly patients. Methods We included patients aged ≥ 65 years with the diagnosis of heart failure. The clinical and laboratory data, echocardiography and ECGs were recorded. Additionally, the frailty scores of the patients were evaluated according to Canadian Study of Health and Aging. All the patients were divided as frail or non-frail. The groups were compared for their characteristics and the occurrence of clinical outcomes. Results We included 86 eligible patients. The median follow-up time was four months. The mean age was 75 ± 6.5 years. Of these 86 patients, 17 (19.7%) patients encountered an event (death and/or hospitalization). Nine patients (10.4%) died during follow-up. Thirty patients (34.9%) were considered frail. Among the demographic, clinical and laboratory data, only total protein and albumin levels were found to be lower in frail patients (total protein level: 6.8 ± 0.6 g/dL in non-frails, 6.5 ± 0.9 g/dL in frails, P = 0.05; albumin level: 3.8 ± 0.4 g/dL in non-frails, 3.4 ± 0.6 g/dL in frails, P = 0.001). In multivariate analysis, frailty was found to be strongly associated with clinical outcomes in short term. Conclusions Being frail in an elderly heart failure patient is associated with death and/or hospitalization due to heart failure in short term. Therefore, frailty score should be evaluated for all elderly heart failure patients as a prognostic marker.

Keywords: Death; Frailty; Heart failure; Hospitalizations

1 Introduction

The prevalence of heart failure (HF) is rapidly increasing,and it is a common cause of hospitalization and death. Hospitalization of older patients can lead to functional deterioration resulting in disability and dependency.[1]The prognosis, risk of rehospitalization, and functional deterioration in HF are mainly evaluated by clinical, laboratory and echocardiographic parameters. The common end point of all these parameters in the elderly HF patient is frailty—a subject of interest which is becoming an increasingly high-priority topic in cardiovascular medicine due to aging. Therefore, frailty is thought to be one of the strong prognostic markers of HF. Frailty is defined as a geriatric syndrome resulting in impaired resistance to stressors (such as illness,surgery, etc.) due to a decline in physiologic reserve.[2]The degree of frailty is determined by old age, associated comorbidities, and disability.[3-5]The decline in physiologic reserve is mainly a consequence of involvement of organ systems.

Frailty is considered to be a high-risk state predictive of a range of adverse health outcomes.[6]One of the most important clinical applications of using frailty is to predict risk of morbidity and mortality of cardiovascular diseases in the elderly. Frailty and cardiovascular diseases share common biological pathways including chronic low grade inflammation.[7]Chronic inflammation results in oxidation of lipoproteins and activation of atheromatous plaques, and acitvates catabolic states especially in the skeletal muscles causing redistribution of amino acids from the musculature.[8,9]As frailty involves multisystem physiologic dysregulation, it is conceivable that chronic inflammation contributes to frailty through its detrimental effects on other physiologic organ systems, such as musculoskeletal and endocrine systems, anemia, clinical and subclinical cardio-vascular diseases, and nutritional dysregulation.[10]Therefore, there is a close association between frailty, inflamation and cardiovascular diseases.

The main objective of our study was to define cardiovascular risks, comorbidities, and frailty in patients aged ≥65 years with HF, and to evaluate the prognostic significance of frailty in these patients.

2 Methods

We included patients aged ≥ 65 years with the diagnosis of HF treated at Cukurova University Hospital, Cardiology Department. The clinical and laboratory data, echocardiography and ECGs were collected and recorded. Additionally, the frailty score of the patients was evaluated by Canadian Study of Health and Aging (CSHA) frailty scoring system.[11]Furthermore, the impact of combined comorbid conditions were quantified according to coronary artery disease (CAD)-specific index.[12]All the scoring systems were evaluated by two cardiologists and one internist separately, and the final scores were recorded upon agreement.The CSHA frailty scale is a 7-point scale of frailty with a good prognostic value depending on clinical judgement.The patients are considered to be frail if the score is ≥ 5.CAD-specific index is a valuable way of evaluation of the impact of combined comorbidity on the clinical status. In this scoring system, each separate major comorbidity (current smoker, hypertension, history of cerebro-vascular event,diabetes mellitus with complications, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral vascular disease, tumor, renal disease, metastatic cancer) has a coefficient, and final score is calculated by the sum of the coefficients. The patients are considered to be at low to moderate risk if the score is 0–3,and high risk if it is ≥ 4.

Patients were followed-up for upto six months.The clinical data, history of hospitalization and death due to progressive HF were recorded in each visit or during hospitalization.The patients without admission during study follow-up period were phone called, and the relevant data were gathered by telephone interview. The major clinical outcomes were death due to progressive HF and combined hospitalization and death due to progressive HF. All the patients enrolled in the study signed written informed consent. The patients who were not willing to participate in the study, and with insufficient clinical information were excluded. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. The study was was approved by the local ethic committee.

For each continuous variable, normality was checked by Kolmogorov Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests and by histograms. Comparisons between groups were applied using the student t test for normally distrubited data, and Mann Whitney U test was used for the data not normally distrubited. All the categorical variables were analyzed by Pearson's chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Univariate analysis was performed to assess the association between death and/or hospitalization due to progressive HF and the possible risk factors including age, sex,hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, smoking, accompanying comorbidities, echocardiographic findings, and frailty score. Logistic regression models were constructed for assessing the independent effect of frailty score on death and/or hospitalization due to progressive HF. The results were presented as odd ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals, as mean ± SD and as n (%). A P value < 0.05 was considered as significant.

3 Results

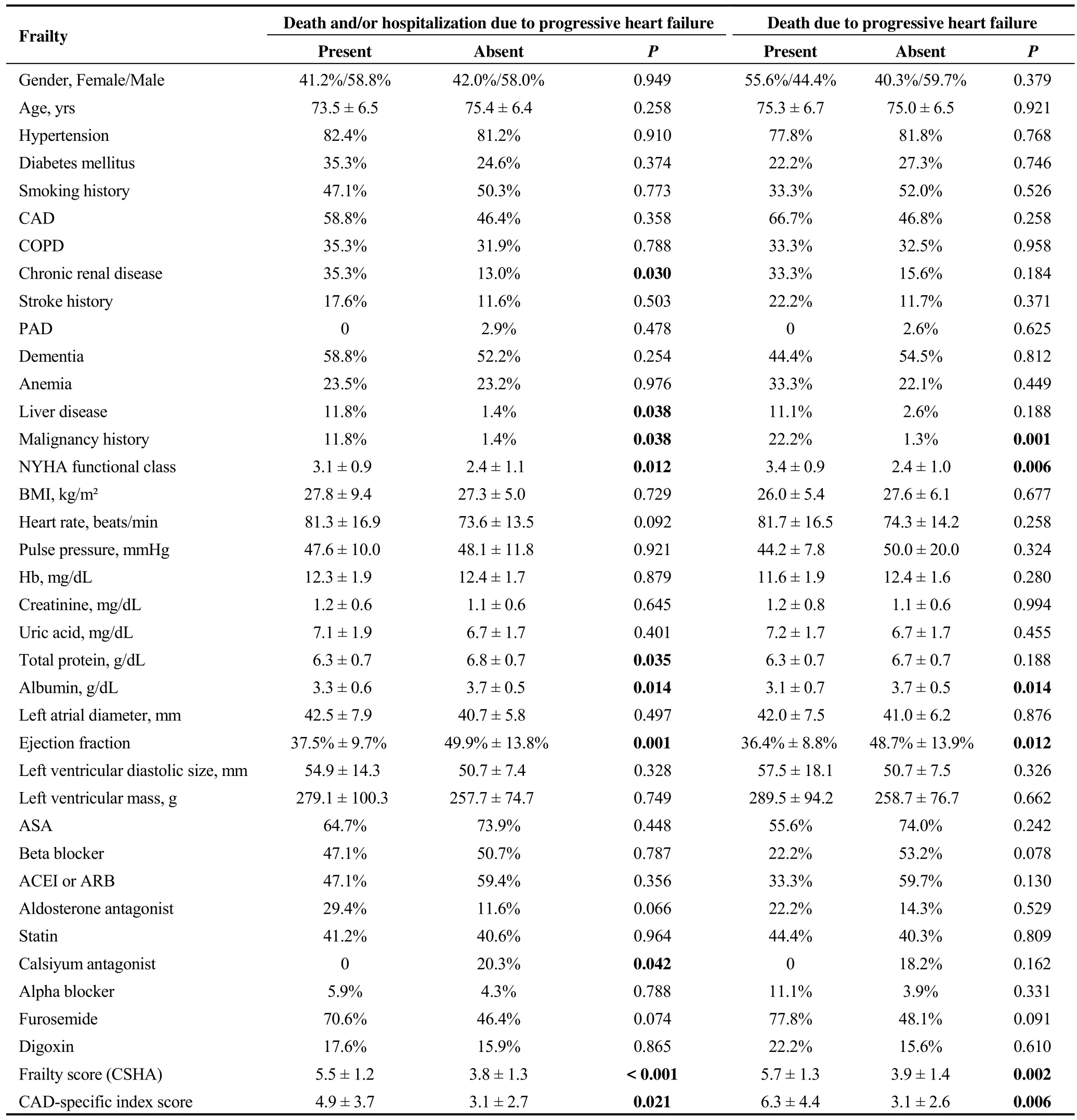

We included 86 patients aged ≥ 65 years with the diagnosis of HF. Baseline characteristics, laboratory data, echocardiographic parameters and frailty scores were compared between the groups (Table 1). The median follow-up time was four months (min: 2, max: 6 months). There was 50 male, and 36 female patients in the whole group. The mean age was 75 ± 6.5 years. Of these 86 patients, 17 (19.7%)patients encountered an event (death and combined death and/or hospitalization). Nine patients (10.4%) died during follow-up. Seven patients were hospitalized more than once.As a comorbidity, 3 patients had malignant diseases, 2 of those with malignancy died during an episode of hospitalization due to decompensation of HF. Thirty patients (34.9%)were considered frail according to CSHA frailty score.When we compared frail and non-frail patients determined according to CSHA, the groups were similar with respect to age, distribution of gender, body mass index, blood pressure,pulse pressure, heart rate, laboratory data with the exception of total protein and albumin levels. Total protein and albumin levels were found to be lower in frail patients (Total protein level: 6.8 ± 0.6 g/dL in nonfrails, 6.5 ± 0.9 g/dL in frails, P = 0.05; albumin level: 3.8 ± 0.4 g/dL in nonfrails,3.4 ± 0.6 in frails, P = 0.001). Regarding echocardiographic findings, left atrium was larger, and ejection fraction (EF)was lower in frail group, although statistically nonsignificant (left atrial diameter: 40.2 ± 6.1 mm in nonfrails, 42.8 ±6.3 mm in frails, P = 0.072; EF: 49.5% ± 13.8% in nonfrails,43.6% ± 13.6% in frails, P = 0.064). The CAD-specific index was also similar between the groups (3.13 ± 2.8 points in nonfrails, 4.13 ± 3.31 points for frails, P = 0.139).

Table 1. Comparison of the the baseline characteristics, laboratory and echocardiographic parameters and frailty scores according to the end points.

In patients reaching an endpoint, the prevelance of chronic renal disease, liver disease, malignancy, NYHA functional class, frailty score and CAD-specific index were found to be significantly higher and albumin levels, EF were found to be significantly lower than the group without death and/or hospitalization due to progressive HF (Table 1).

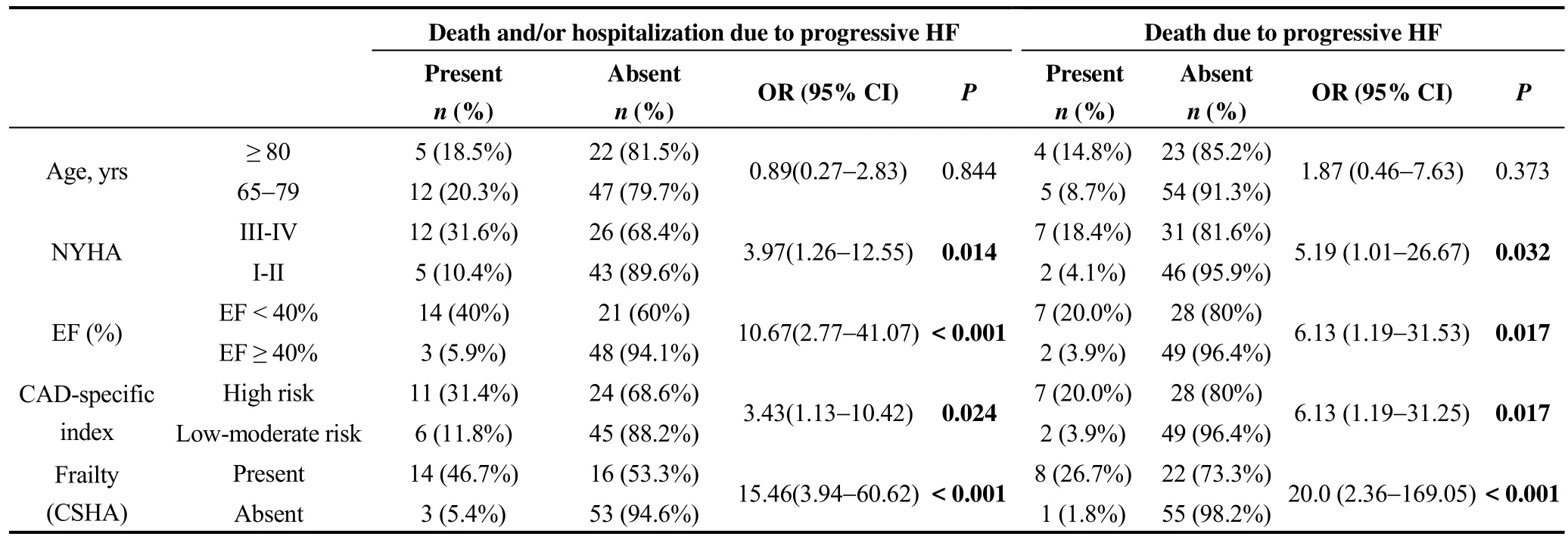

The patients who encountered an event (death and combined death and/or hospitalization due to progressive HF)were categorized and compared according to their age(65-79 and ≥ 80 years), ejection fraction (EF ≥ 40 % and EF < 40%), functional capacity [New York Heart Association (NYHA) I-II and NYHA III-IV], and frailty (score ≥ 5 and < 5) (Table-2). Reduced EF (< 40%) is associated with significantly higher risk for combined death and/or hospitalization due to progressive HF [14 (40%) vs. 3 (5.9%), P <0.001] and higher risk for death due to progressive HF [7(20%) vs. 2 (3.9%), P = 0.017). High NYHA group (III and IV) is associated with significantly higher risk for both end points [12 (31.6 %) vs. 5 (10.4 %), P = 0.014 for combined end points, 7 (18.4%) vs. 2 (4.1%), P = 0.032 for death due to HF]. Higher CAD-specific index is associated with significantly higher risk for death and/or hospitalization due to HF group [11 (31.4%) vs. 6 (11.8%), P = 0.024] and death due to HF group [7 (20%) vs. 2 (3.9%), P = 0.017]. Similar results are seen on CSHA frailty index. Higher CSHA frailty score is associated with increased death and/or hospitalization and death due to progressive HF [14 (46.7%) vs.3 (5.4%), P < 0.001 and 8 (26.7%) vs. 1 (1.8), P < 0.001](Table 2).

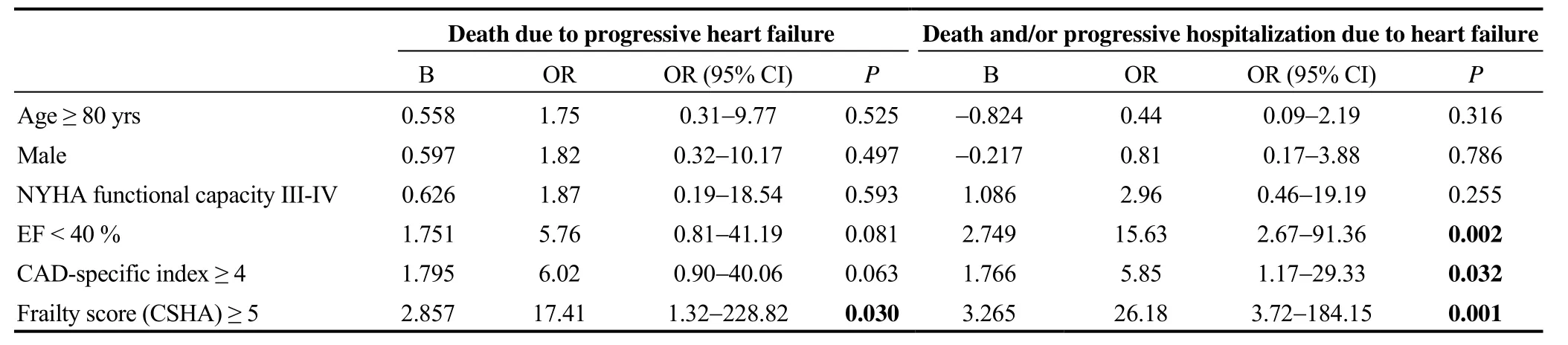

When we compared the aforementioned risk factors by multivariate analysis, CSHA frailty score ≥ 5 is significantly associated with death due to progressive HF for short term follow-up (OR = 17.41; 95% confidence interval (CI):1.32-228.82, P = 0.030). Reduced EF (< 40%) (OR = 15.63;95% CI: 2.67-91.36, P = 0.002), CAD-specific index (OR= 5.85; 95% CI: 1.17-29.33, P = 0.032) and CSHA frailty score ≥ 5 (OR = 26.18; 95% CI: 3.72-184.15, P = 0.001)are significantly associated with death and/or hospitalization due to progressive HF (Table 3).

4 Discussion

The main finding of our study is the demostration of frailty to be one of the most powerful risk predictors of death and/or hospitalization due to progressive HF. Our prospective cohort study addresses the importance of classifying elderly HF patients according to their frailty status to predict the development of important health outcomes during short term follow-up.

Along with the increase in life expectancy of the general population, the number of critically elderly ill patients increases. However, the survival of very old age group is still rather poor.[13,14]In addition, HF is characterized by a frequent instability, and until now the factors determining the rehospitalization of decompensated HF patients are not completely identified.

Table 2. Univariate analysis of major prognositic parameters in HF patients.

Table 3. Comparison of the the risk factors according to the end points by multivariate analysis.

The frailty has been defined as a clinical state of increased vulnerability from age-associated decline in physiological reserves and functions in a wide range of physiological systems.[15]The identification of frailty in patients with HF is important from the clinical point of view, as this condition exerts unfavorable effects on the course of HF. The American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology and the Society of Geriatric Cardiology have emphasized the role of frailty in cardiovascular diseases.[16]In our study, we demonstrated that reduced EF (< 40%), being NYHA III and IV and high CSHA frailty score were associated with significantly higher risk in death and/or hospitalization due to progressive HF.

All of our study population had a substantial proportion of heart failure patients which may have increased the mean frailty score in this cohort, and may influence the generalizability of our results. This study was not designed to make recommendations about routine frailty screening. Frailty is common end point for most of the chronic diseases, and also because frailty may result in chronic inflammation, hypothetically it may cause disease progression. So, it is chicken and egg paradox.

It is worth noting that in our study, high risk in CAD-specific index is associated with higher risk for death and/or hospitalization due to progressive HF and death due to progressive HF. Frailty occurs in 25%-50% of patients with cardiovascular diseases depending on the measurement scale of frailty. Besides, frail patients with cardiovascular diseases, especially those undergoing invasive methods such as PCI, are more likely to have more adverse effects than people without frailty.[17]

In many previous studies, it is found that the intensive care unit (ICU) mortality range changes from 14% to 46% and hospital mortality range changes from 28% to 48%.[13,18]Using a frailty index, one study found a strong association between increased frailty and 90-day mortality.[19]In a Canadian study, a lower index on a frailty scale was independently associated with increased survival in 610 patients followed for 12 months.[20]A recent multi-centre American study found an association between greater degree of frailty, measured with the Clinical Frailty Scale and higher risk of mortality.[21]We also showed frailty to be strongly associated with mortality and combined outcome of death and hospitalization. This finding is compatible with the evidence demonstrating the prognostic role of frailty.[22]The CSHA frailty scoring system is easy to classify frailty status, and it is adequate for clinical practice. Our findings demonstrate the feasibility of using the CSHA in the HF patient population. Also, we think that this simple-to-use clinical frailty scale should be a component risk for evaluation of elderly HF patients.

End-organ disease such as HF exacerbates frailty. It is unclear, however, if frailty itself can contribute to organ dysfunction and resultant HF. One study found that in community-dwelling individuals, moderate and severe frailty have an increased risk of incident heart failure diagnosis.[23]While there is no direct relationship between frailty and severity of HF, there is evidence that frailty is more common with acute decompensated HF as compared to those with preserved and reduced EF.[24]

In our study, we also found that high NYHA functional class (III and IV) was associated with significantly higher risk for death and/or hospitalization due to HF and death due to progressive HF. Dunbar, et al.[25]have demonstrated that HF patients with high frailty score had worse NYHA functional class indicating the high clinical severity of the condition. Therefore, it seems that a deterioration of functional capabilities and an increase in symptom severity naturally lead to increased frequency of hospitalization in HF.

The relationship between inflammation and frailty is complex since both linearly increase with advancing old age.[26]Frail participants have a higher presence of concomitant factors like disability, medical conditions that could increase the inflammatory parameters. Studies have shown that elevated cellular and molecular inflammatory mediators have inverse associations with levels of albumin.[27]In our study, we found a relation between death and/or hospitalization and low albumin level. This result may reflect the relationship between inflammation and frailty. Also, there is growing evidence suggesting that nutrition is important and a modifiable factor potentially affecting the frailty status of the older person. It is evident that nutritional interventions may potentially improve the older person’s risk profile by improving fraility status.[28]

Frailty is generally considered to be a geriatric syndrome.Individuals with chronic diseases, such as chronic kidney disease (CKD), may be at risk for premature frailty. Some studies reported a high prevalence of frailty among elderly individuals with mild to moderate CKD. They concluded that CKD may be a major contributor to the development of frailty.[29]In our study, CKD was found to be significantly higher in group with combined endpoint of death and/or hospitalization due to progressive HF.

In our study, we found an association between death and/or hospitalization and malignancy history. In the literature,prevalence of frailty and pre-frailty in older cancer patients is high.[30]Routine assessment of frailty in older cancer patients may have a role in guiding treatment. Failure to detect frailty potentially exposes older cancer patients to treatments from which they might not benefit, and indeed may be harmed.

There were some limitations in this study. Although it is a prospective study, our results came from a single center with relatively small number of patients. Therefore, a larger sample size study would allow other independent variables in the regression analysis to examine the relation between frailty and clinical outcomes. We did not have a control group from the general population of our hospital and we have no long-term survival outcome data in our study. This was not within the scope of the study. In our study, only salt restriction diet (less than 5000 mg/day) was applied and no other protein-related diet program was applied. Also, the chosen way of measuring frailty is subjective and may have a higher inter-rater variability than more objective measures of frailty. In our study, we did not provide a treatment protocol specifically for fragility. We have just applied the heart failure routine treatment algorithm.

In conclusion, high frailty score in elderly HF patients is valuable to predict major adverse outcomes, particularly death and hospitalization due to progressive HF. Future studies are required to more precisely clarify the role of frailty in prognosis of HF, and improve management of patients depending on their frailty status.

Acknowledgements

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2018年11期

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2018年11期

- Journal of Geriatric Cardiology的其它文章

- Atypical electrocardiographic manifestations of ischemia: a case of dynamic Wellens patterns

- Inoperable severe aortic valve stenosis in geriatric patients: treatment options and mortality rates

- Chemical renal artery denervation with appropriate phenol in spontaneously hypertensive rats

- Increased index of microcirculatory resistance in older patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- Prevalence of iron deficiency in patients aged 75 years or older with heart failure

- Association of invasive treatment and lower mortality of patients ≥ 80 years with acute myocardial infarction: a propensity-matched analysis