Non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome in the elderly

Pablo Díez-Villanueva, César Jiménez Méndez, Fernando Alfonso

Cardiology Department, Hospital Universitario La Princesa, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain

Keywords: Acute coronary syndrome; Myocardial infarction; The elderly

1 Introduction

Societies are ageing at an accelerated pace. This scenario is a well-known challenge for health care systems, as chronic diseases, multiple comorbidities and dependency are all entities that often converge in the elderly. Besides, there is an issue regarding a reduction in the general incidence of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) together with a delayed in the age of presentation, which, in sum, lead to an increase in both incidence and prevalence of ACS with age, especially non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). On the other hand, ageper seis one of the most important predictors of mortality but also morbidity in the setting of ACS,thus being present in most risk scores for ischemic and haemorrhagic events in this scenario.[1]

2 Management of NSTEMI in the elderly

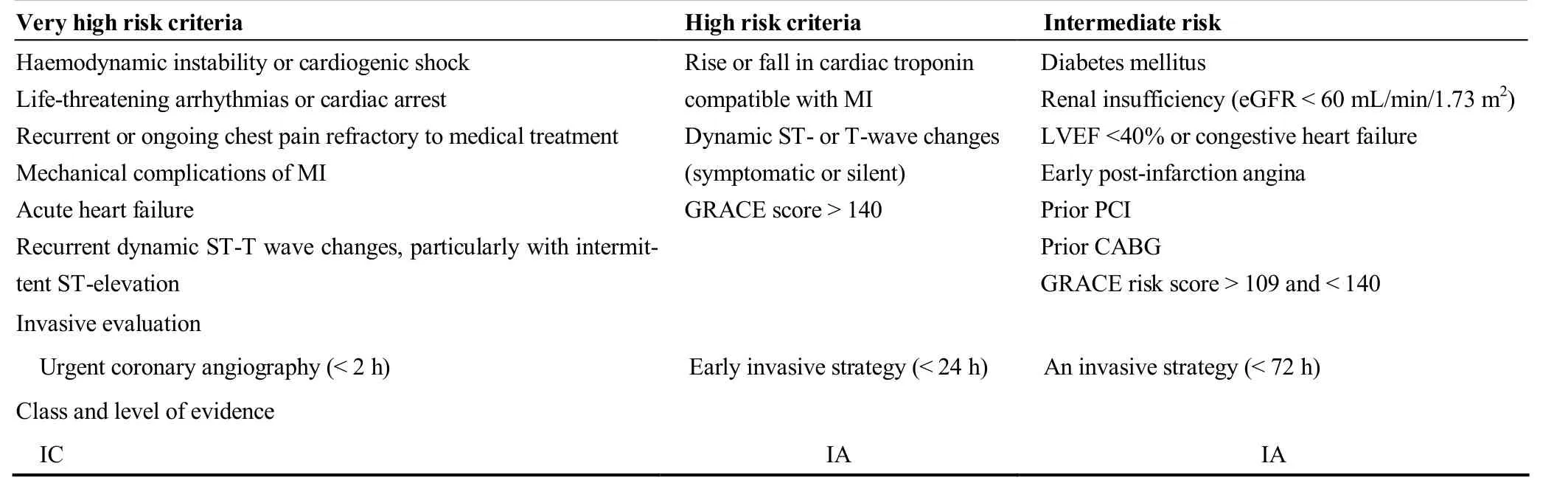

In patients with NSTEMI, the initial therapeutic objective is to stop the thrombogenic cascade by the administration of antithrombotic drugs (antiplatelets and anticoagulation),decrease myocardial oxygen demand (by decreasing heart rate, blood pressure, preload and myocardial contractility)and increase myocardial oxygen supply (by coronary vasodilation or administration of oxygen). According to current European Society of Cardiology guidelines, a prompt diagnosis is mandatory, as an early invasive strategy is recommended in most patients with NSTEMI (Table 1). High clinical suspicion is essential, especially in elderly patients,whose clinical presentation is often atypical, thus leading to a delayed diagnosis, which entails worse prognosis.[2]

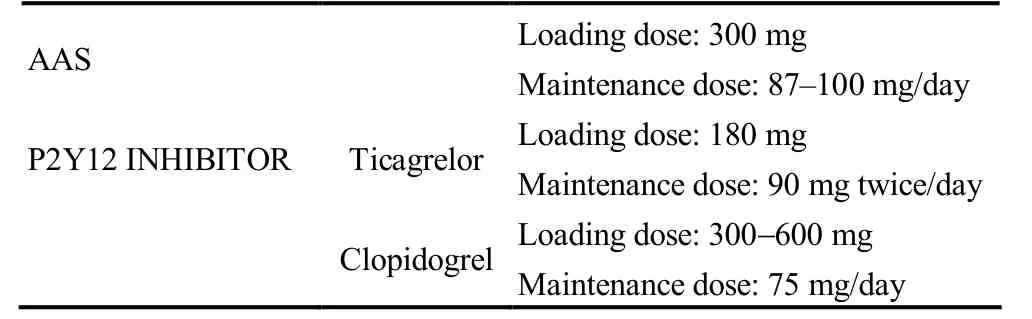

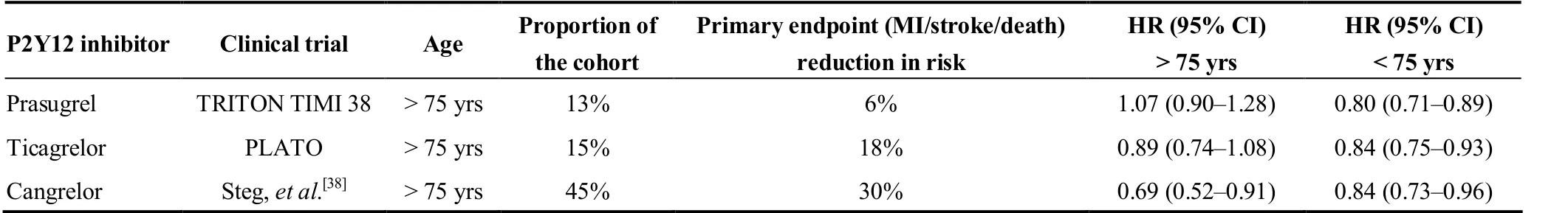

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) is recommended in all NSTEMI patients, and constitutes the cornerstone of the medical therapy.[3]This combination associates lower events at the expense of an increase in bleeding risk. Both the choice of antithrombotic agent and dosage should be individually addressed, particularly in the elderly, as ageing is associated with increased bleeding risk, which is related to physiological changes involving liver and renal impairment,drug interactions and comorbidities. Clinical guidelines recommend the use of a potent P2Y12 inhibitor—ticagrelor or prasugrel—instead of clopidogrel, unless contraindicated,in all patients with an ACS, in addition to aspirin, at the time of index event and to continue this therapy for 12 months, irrespective of treatment strategy, as shown in Table 2.[4]Nevertheless, elderly patients are often underrepresented on clinical trials (Table 3) and different registries have shown that clopidogrel is the agent most often used in the elderly, as this drug seems to be associated with a lower rate of bleeding events, showing a safer profile when compared with the more potent agents prasugrel and ticagrelor.[5]Indeed, prasugrel did not demonstrate a net clinical benefit in patients aged over 75 compared to clopidogrel, because of significantly increase in fatal and lifethreatening bleedings.[6]As a consequence, prasugrel is not recommended for patients over 75 years old in this scenario by the European Medical Agency (EMA). Half-dose prasugrel (5 mg/day) has also been compared to regular-dose clopidogrel in patients over 75 years with ACS undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI); the Elderly ACS 2 trial showed that half-dose prasugrel was not superior in reducing ischemic events in this population.[7]Recently,there has been a sizeable upward trend in the use of the reversible P2Y12 inhibitor ticagrelor in this population.[8]

In a substudy of the LONGEVO-SCA registry (Impacto de la fragiLidad y Otros síNdromes GEriátricos en el manejo y pronóstico Vital del ancianO con Síndrome Coronario Agudo sin elevación de segmento ST), 15% of 413 octogenarian patients with NSTEMI were discharged with aspirin and ticagrelor. These patients were slightly younger, with less comorbidities and with a lower profile ofischemic and haemorrhagic risk, when compared with those who received clopidogrel instead.[9]Interestingly, more than 85% of patients treated with ticagrelor had high risk criteria for haemorrhagic complications according to risk scores such as PRECISE-DAPT.[10]The incidence of bleeding at 6 months was 3.2%, lower than expected. Authors concluded that elderly patients with NSTEMI properly selected, can be safely treated with ticagrelor despite their theoretical higher haemorrhagic risk profile.[9]On the other hand, the POPular-Age trial (randomized comparison of clopidogrel versus ticagrelor or prasugrel in patients of 70 years or older with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome) results have been recently disclosed. This randomized trial showed that NSTEMI patients over 70 years old treated with clopidogrel were associated with less bleeding rates compared with those treated with a more potent P2Y12 inhibitor (such as ticagrelor or prasugrel). Ischemic events rates were similar in both groups, showing non-inferiority of clopidogrel.[11]

Table 1. Risk criteria in NSTEMI.

Table 2. Initial and maintenance doses of antiplatelet drugs as recommended in clinical guidelines.

Parenteral anticoagulation treatment is recommended in NSTEMI patients at the time of diagnosis. Fondaparinux has the most favourable efficacy-safety profile and it is recommended regardless of the management strategy. Alternatively, treatment with low molecular weight heparin or even unfractionated heparin could be considered. NSTEMI patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) merit special attention as AF is the most prevalent cardiac arrhythmia in the elderly population, and adds both ischemic and haemorrhagic risks.When oral anticoagulation is indicated, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) are preferred over warfarine/acenocumarol, excepting those with valvular AF.[12]Regarding antithrombotic and anticoagulant regimen of treatment, ESC guidelines recommend the combination of oral anticoagulation plus dual antiplatelet therapy (with clopidogrel)—also known as “triple therapy”—for at least one month after the index event in most patients unless concerns about bleeding risk prevail. After that, single antiplatelet therapy combined with oral anticoagulation should be mantained for 12 months. Those with low bleeding risk should stay on triple therapy until 3-6 months after PCI. NOACs have demonstrated in several clinical trials their benefits when combining with antiplatelet therapy in this setting. However,there is no specific clinical trials focused on the elderly population.

Table 3. Clinical trials and elderly population representation.

3 Ischemic and haemorrhagic risk in the elderly

Ischemic and haemorrhagic risk stratification in the elderly represent a clinical challenge, mainly due to the complexity of the interaction between cardiovascular risk factors,comorbidities, frailty and other geriatric syndromes. As mentioned before, age is known to be an independent risk factor for thrombotic and bleeding events in the setting of ACS.

In NSTEMI, quantitative assessment of ischaemic risk by means of scores is superior to the clinical assessment alone.Several prognosis scales have been recently developed, predicting ischemic and haemorrhagic risks either on admission or at discharge.

3.1 On admission risk scores

(1) GRACE score provides mortality risk while in hospital, at 6 months, at 1 year and at 3 years. The combined risk of death or MI at 1 year is also provided. It has been validated in the elderly population.[13]

(2) The thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI)risk score also provides risk while in hospital and is considered to be easier to use. However, its discriminative accuracy is lower.[14]

(3) The use of CRUSADE bleeding score is a IIB recommendation in order to estimate the bleeding risk in patients undergoing PCI.[2]It combines baseline patient characteristics, admission clinical variables and admission laboratory values. However, predictable values on elderly population are not as accurate as in younger NSTEMI patients.[15]

3.2 Risk scores at discharge

The PRECISE-DAPT score for bleeding risk stratification has been widely used in patients undergoing PCI.[16]A recent study has shown that most elderly patients have PRECISE-DAPT values above the cut-off point for high bleeding risk (PRECISE-DAPT score ≥ 25). No significance differences were found in the incidence of bleeding.Consequently, it could be recommended to adapt PRECISE-DAPT score and use different cut-off values for this population.[17]

4 Invasive strategy in NSTEMI

An invasive coronary angiography approach is recommended in the majority of patients with NSTEMI as stated in current ESC Guidelines.[2]This decision should be carefully made by addressing both the risks and benefits regarding this indication and the timing for myocardial revascularization. It depends on various factors such as comorbidities, clinical presentation, frailty, estimated life expectancy,etc. However, the fact is that elderly patients are less likely to be revascularized. The GRACE registry showed that coronary angiography was performed in 33% of patients over 80 years, compared with the 67% of patients under 70 years.[18]Also, a revascularization rate of 12.6% of patients over 90 years and 40.1% of patients between 70 and 89 years was observed in the CRUSADE initiative.[19]

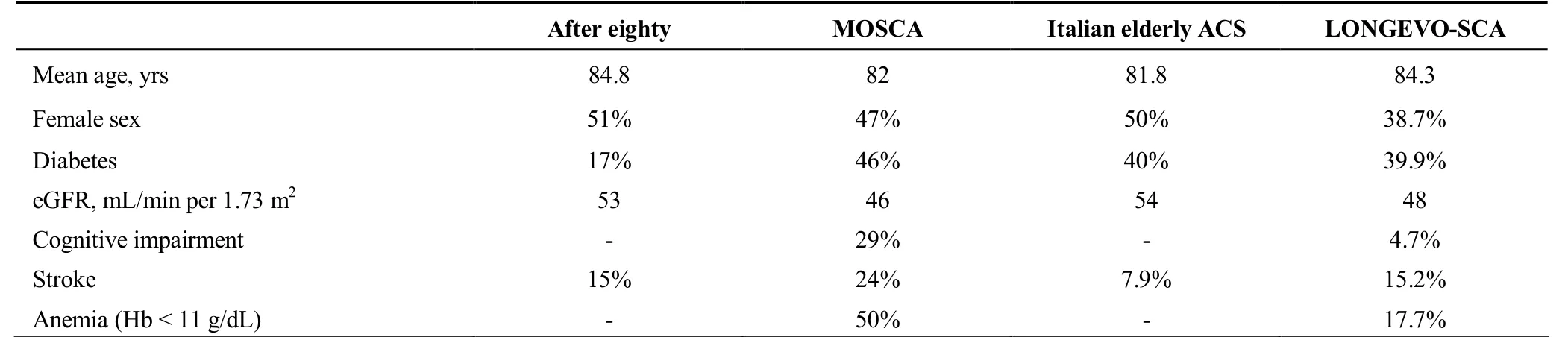

The impact of invasive treatment on elderly population has been specifically studied in some clinical trials. Table 4 provides a summary of the clinical features of the main studies discussed below. The Italian ACS Elderly Trial included 313 patients > 75 years of age with NSTEMI, randomized to early invasive strategy or a conservative approach. There were no differences in primary outcome (a composite of death, myocardial infarction, disabling stroke,and repeat hospital stay for cardiovascular causes or severe bleeding within one year). Recently, the After Eighty clinical randomized 457 patients > 80 years to invasive versus conservative strategy, there was a lower incidence of the composite endpoint of myocardial infarction, need for urgent revascularisation, stroke, and death in the invasive group. Even more recently, MOSCA-frail clinical trial included 106 patients over 70 years with high degree of comorbidity defined as peripheral artery disease, cerebral vascular disease, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease,chronic renal failure or anaemia.[20]There were no differences between a conservativevs.invasive strategy in therate of all-cause mortality, reinfarction and readmission for cardiac cause at 2.5-year follow-up. However, it has to be considered that patients included in MOSCA-FRAIL trial were noticeable more frail. Information about the role of an invasive strategy in elderly patients with NSTEMI according to frailty status is scarce. A sub-study of LONGEVOSCA registry demonstrated that the incidence of cardiac events was more common in patients managed conservatively and remained significant in non-frail patients.[21]However, this association was not relevant in frail patients(defined as ≥ 3 in the FRAIL scale).

Table 4. Impact of invasive treatment in elderly patients with NSTEMI.

Technical aspects should also be taken into account in the decision-making process regarding invasive management, especially in the elderly population. Radial approach is preferred over femoral access in coronary angiography, as it reduces the bleeding risk related with PCI. The use of new-generation drug eluting stent (DES) should be preferred over bare-metal stent (BMS) for any PCI as demonstrated on LEADERS FREE trial. This trial randomized 2466 high bleeding risk ACS patients (mostly NSTEMI)with PCI indication into drug-eluting stent use (DES-Biolimus) versus bare metal stent use (BMS). After 12 months of follow-up, DES met superiority criteria for both its primary safety endpoint of cardiac death/MI/stent thrombosis(HR = 0.48, 95% CI: 0.31-0.75;P= 0.001) and its primary efficacy endpoint of target lesion revascularization (TLR) at one year (HR = 0.41, 95% CI: 0.21-0.82;P= 0.009).[22]The SENIOR clinical trial also showed that among elderly patients who have PCI, a DES and a short duration of DAPT are better than BMS and a similar duration of DAPT with respect to the occurrence of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, stroke, and ischaemia-driven target lesion revascularisation (HR = 0.71, 95% CI: 0.52-0.94,P=0.02).[23]When assessing ischemic and haemorrhagic risk, it should also be considered patient’s previous prescriptions,such as adding a proton pump inhibitor and avoiding non-steroid antiinflamatory drugs in this setting.[24]

5 Specific geriatric conditions

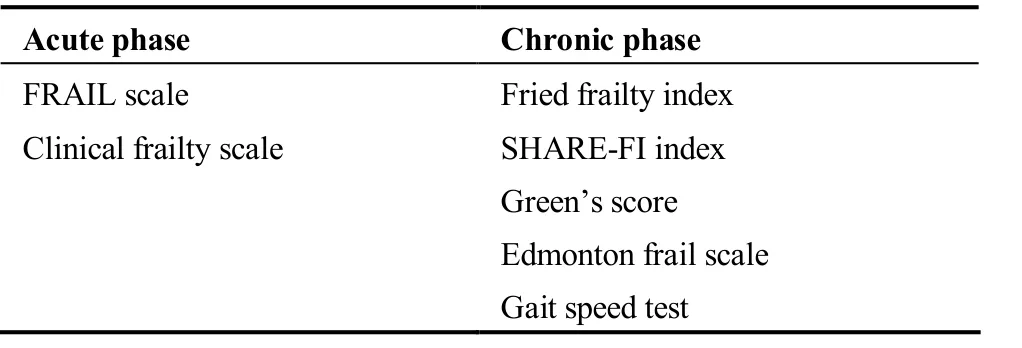

The assessment of frailty and other geriatric syndromes has been of growing interest, regarding their impact in terms of morbidity and mortality during short and long term follow up. As a consequence, different scales have been developed in order to measure them during the acute but also in the chronic phase (Table 5).

Frailty is a condition defined as a loss of biological reserve, which leads to impaired response to stressor events.[25]Frailty has become a substantial factor in assessment of several special medical situations and has been establishedas a crucial issue into clinical decision making. Furthermore,the pathophysiologic mechanism of this condition, like higher markers of thrombosis (D-dimer), endocrine unbalances, elevated inflammatory state (C-reactive protein and interleukin-6) and higher oxidative stress levels, contribute to the onset and outcome of ACS.

Table 5. Frailty scales on acute or chronic phase.

Furthermore, it has been identified as a strong independent predictor of in-hospital and 30-day mortality in elderly patients presenting with NSTEMI. Among elderly patients admitted with ACS, 10% of > 65 years and 25%-50% of >85 are considered frail. Frailty has been demonstrated to increase the all-cause mortality risk by 2.65-fold, any-type cardiovascular disease risk by 1.54-fold, major bleeding risk by 1.54-fold and hospital readmissions risk by 1.51-fold.[26]A prospective observational study of 270 elderly patients admitted for NSTEMI showed that PCI in patients with Fried score ≥ 3 was associated with a significant reduction of risk of all-cause and cardiovascular rehospitalizations without reducing all-cause mortality (median follow-up 4.4 years).[27]Finally, frailty should be considered as a therapeutic goal is one of the future hotspot of research. Treatment of frailty with general measures, as cardiac rehabilitation or deprescription, is related with less mortality and morbidity rates. It is already known that frailty is an important biological condition that should be regularly measured.Accordingly, measurement and treatment of frailty will be an essential point in our clinical practice in the present and future.

Nutrition is another condition that adversely impacts prognosis in these patients. Nutritional assessment has been recently published as an independent predictor of mortality in elderly patients with ACS. Interestingly, Tonet,et al.[28]using the Mini Nutritional Assessment-Short Form (MNASF) classified a 908 patients population into malnutrition(4% of the sample), high risk of malnutrition (31%) and no risk of malnutrition. After a follow-up of 288 days, the mortality rates were 3% in the no malnutrition group, 19%in the high-risk of malnutrition group and 31% in the malnutrition population (P< 0.001). MNA-SF score was an independent predictor of mortality (HR = 0.76, 95% CI:0.68-0.84). Some smaller studies have showed similar results underlighting the importance of incorporating MNASF score in daily practice.[29]Therefore, strategies to improve nutrition state in the elderly should be implemented.

Delirium is yet another important situation of elderly patients with NSTEMI. This is a common clinical syndrome characterized by inattention and acute cognitive dysfunction.It is a transient, acute, fluctuating and reversible syndrome. Delirium can have a widely variable presentation,and is often missed and underdiagnosed as a result. The incidence of delirium in hospitalized patients is variable,while an incidence of 20% has been reported in patients admitted to cardiac intensive care units,[30]while it has been significantly associated with longer hospitalizations as well as higher incidence of 6-month events and higher mortality in octogenarians with NSTEMI.[31]Thus, measures to prevent delirium should be included in daily clinical practice.This condition can be prevented by avoiding precipitating drugs (benzodiazepines), contributing to maintain orientation even providing clocks or calendars, ensuring adequate hydration and nutrition, aiming the use of hearing or visual aids and early mobilisation.

Contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) is an entity more prevalent in the elderly population. It is known that the risk is increased when the ratio of total contrast volume to glomerular filtration rate (in ml/min) is over 3.7. Recent myocardial revascularization guidelines recommend the assessment for the risk of contrast-induced nephropathy in all patients and an adequate pre and post hydration is recommended at the time of performing a coronary angiography. Pre-treatment with high-dose statin could be beneficial also in this setting. Previous renal impairment, which is high prevalent between aging population, is also a risk factor for CIN. In this case, using low-osmolar or iso-osmolar contrast media is recommended and hydration with as much as 1 mL/kg per hour of isotonic saline 12 hours before and after the procedure is suggested if the contrast volume is over 100 mL.[4]

6 Secondary prevention

Secondary prevention should be encouraged in all NSTEMI patients, especially older ones, regarding their higher ischemic risk. Higher rates of recurrent cardiovascular events have been reported in the older population, such as 7.2% of recurrent myocardial infarction, 6.7% of recurrent ischemic stroke in the first year and a 32% of death.[32]Those secondary measures should include therapies like β-blockers, ACE inhibitors and statins, as well as enrolment in cardiac rehabilitation programmes and lifestyle changes such as smoking cessation. Lipid-lowering therapies are an essential part of the treatment of patients after an ACS.Current guidelines recommend the use of high-dose statins.Although these recommendations are widely known for clinicians, registries have showed that only 15% of patients over 80 years discharged after an ACS receive statins. This could be associated with the evidence that statins have been previously suggested to be beneficial in primary prevention only under 75 years.[33]Moreover, the efficacy of statins with respect to secondary prevention has been challenged in elderly patients, although this evidence is controversial.[34]On the other hand, a sub-study of IMPROVE-IT trial (Improved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial) analysed the impact of intensive statin therapy across age groups in ACS patients. After 7 years, the primary endpoint (a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, unstable angina requiring rehospitalization, coronary revascularization, or nonfatal stroke)underwent an absolute risk reduction of 8.7% for patients 75 years or older (HR = 0.80; 95% CI: 0.70-0.90). The number needed to treat (NNT) was 11 in > 75 years groupvs.125 in< 75 years group. There was no difference in adverse effects rates (rhabdomyolysis, myopathy or transaminases alterations). In fact, moderate doses have been proposed to be as effective as high doses in elderly patients, regarding the fact that polypharmacy and the risk of drugs interactions are common in this population.[35]

Nonetheless, a recent study showed that although most octogenarians are already on statins before an ACS episode,many of them do not receive statins at discharge because of their high-risk profile, with significant frailty and comorbidity.[36]

Finally, enrolment in cardiac rehabilitation programmes provides substantial benefits in the elderly after an ACS.The EU-CaRE trial showed better drug adherence and functional capacity in those patients with an earlier enrolment. A trial with NSTEMI patients over 70 years randomized to cardiac rehabilitation during 1 year versus clinical follow-up showed a better cardiovascular risk factors control (OR =2.18, 95% CI: 1.36-3.50), better Mediterranean diet adherence and better functional capacity (evaluated by Short Physical Performance Battery scale, SPPB).[37]

7 Conclusions

Despite increasing evidence, management of NSTEMI elderly patients remains a challenge. It will become a priority for cardiologists in the following years. Assessment of ischemic and haemorrhagic risks is of paramount importance in all NSTEMI elderly patients. In general, elderly patients with ACS with low frailty scores should be managed as younger patients, including coronary revascularization and use of antithrombotic drugs. Specific therapies should be implemented during hospitalization, in order to prevent functional decline, increase nutritional state and avoid delirium. Early detention of frailty is mandatory.Therefore, multidisciplinary approaches are needed in order to provide the best treatment to these patients.

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2020年1期

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2020年1期

- Journal of Geriatric Cardiology的其它文章

- Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia during phase II cardiac rehabilitation in a patient with heart failure: a case report

- “One-man” bailout technique for high-speed rotational atherectomy—assisted percutaneous coronary intervention in an octogenarian

- Aspergillus infection of pacemaker in an immunocompetent host: a case report

- Is dual therapy the correct strategy in frail elderly patients with atrial fibrillation and acute coronary syndrome?

- A meta-analysis of 1-year outcomes of transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in low-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis

- Anemia in patients with high-risk acute coronary syndromes admitted to Intensive Cardiac Care Units