Anemia in patients with high-risk acute coronary syndromes admitted to Intensive Cardiac Care Units

Victòria Lorente, Jaime Aboal, Cosme Garcia, Jordi Sans-Roselló, Antonia Sambola, Rut Andrea,Carlos Tomás, Gil Bonet, David Vi?as, Nabil el Ouaddi, Santiago Montero, Javier Cantalapiedra,Margarida Pujol, Isabel Hernández, María Pérez-Rodriguez, Isaac Llaó, José C Sánchez-Salado,Miquel Gual, Albert Ariza-Solé,#; on behalf of the Grup de Treball de Cures Agudes Cardiològiques de la Societat Catalana de Cardiologia

1Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain

2Hospital Unversitari Josep Trueta, Girona, Spain

3Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol Badalona, Barcelona, Spain

4Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Instituto de Investigación Biomédica IIB Sant Pau, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB), Barcelona, Spain

5Hospital Universitari de la Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona, Spain

6Hospital Clínic i Provicial, Barcelona, Spain

7Hospital Arnau de Vilanova, Lleida, Spain

8Hospital Joan XXIII, Tarragona, Spain

Abstract Background Little information exists about the role of anemia in patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS) admitted to Intensive Cardiac Care Units (ICCU). The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of anemia and its impact on management and outcomes in this clinical setting. Methods All consecutive patients admitted to eight different ICCUs with diagnosis of non-ST segment elevation ACS(NSTEACS) were prospectively included. Anemia was defined as hemoglobin < 130 g/L in men and < 120 g/L in women. The association between anemia and mortality or readmission at six months was assessed by the Cox regression method. Results A total of 629 patients were included. Mean age was 66.6 years. A total of 197 patients (31.3%) had anemia. Coronary angiography was performed in most patients(96.2%). Patients with anemia were significantly older, with a higher prevalence of comorbidities, poorer left ventricle ejection fraction and higher GRACE score values. Patients with anemia underwent less often coronary angiography, but underwent more often intraaortic counterpulsation, non-invasive mechanical ventilation and renal replacement therapies. Both ICCU and hospital stay were significantly longer in patients with anemia. Both the incidence of mortality (HR = 3.36, 95% CI: 1.43-7.85, P = 0.001) and the incidence of mortality/readmission were significantly higher in patients with anemia (HR = 2.80, 95% CI: 2.03-3.86, P = 0.001). After adjusting for confounders, the association between anemia and mortality/readmission remained significant (P = 0.031). Conclusions Almost one of three NSTEACS patients admitted to ICCU had anemia. Most patients underwent coronary angiography. Anemia was independently associated to poorer outcomes at 6 months.

Keywords: Acute coronary syndromes; Anemia; Intensive cardiac care units; Prognosis

1 Introduction

Anemia is a common clinical condition in patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS), especially in elderly patients with comorbidities.[1]The progressive ageing of population is leading to an increase in the number of patients with ACS and anemia.[2]Importantly, patients with anemia are usually excluded from clinical trials, and information regarding their optimal management is scarce.[3]Patients with anemia are commonly managed conservatively in routine clinical practice.[4,5]In a not negligible proportion of cases, these patients are denied intensive therapies because of perception of short life expectancy and fear of complications. Little information exists about anemia in ACS patients admitted to intensive care units.[6,7]The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of anemia and its impact on management and outcomes in consecutive patients with non ST segment elevation ACS (NSTEACS)admitted to Intensive Cardiac care Units (ICCU).

2 Methods

2.1 Design and study population

This is a multicenter registry carried out in eight hospitals of Catalonia during a period of 6 months (between October 1, 2017 to March 31, 2018). This study was endorsed and coordinated by the Working Group on Acute Cardiac Care of the Catalan Society of Cardiology.

All consecutive patients admitted to the ICCUs of the participating centers with a diagnosis of NSTEACS were prospectively included. NSTEACS was defined as the presence of chest pain compatible with acute coronary syndrome with at least one of the following: (1) electrocardiographic abnormalities suggesting myocardial ischemia and(2) elevation of troponin. The only exclusion criteria was the impossibility of obtaining informed consent for participation in the registry.

2.2 Data collection

Data were prospectively collected during admission by local researchers, using specific standardized case report forms. Demographic data, baseline clinical characteristics,analytical, electrocardiographic and echocardiographic data were recorded, as well as the performance of coronary angiography. Information about in-hospital clinical course(treatments administered, requirement of invasive procedures, complications and in-hospital mortality) was also collected. The CRUSADE[8]and GRACE[9]risk scores were calculated for each patient. The hemodynamic parameters(heart rate, systolic blood pressure) and Killip class were recorded upon admission to the ICCU. Creatinin clearance was calculated by the Cockcroft-Gault formula.[10]Body surface area was calculated using the Mosteller formula.[11]Anemia at admission was defined by the World Health Organisation criteria (hemoglobin < 130 g/L in men and <120 g/L in women).[12]

Patients’ risk profile was defined by the criteria of the European Society of Cardiology.[13]Patients with very high risk were considered those who presented at least one of the following conditions: refractory angina, hemodynamic instability, cardiogenic shock, acute heart failure, ventricular arrhythmias or cardiorespiratory arrest. Likewise, high-risk patients were considered those with elevated serum troponin,diabetes mellitus or GRACE scale values > 140, without very high risk criteria.

Management of patients was done according to current recommendations. Antithrombotic treatment and coronary angiography were left to the discretion of the medical team.If coronary angiography was performed, vascular access,antithrombotic drugs and the choice of stents and other devices were lead to operator’s decision.

Clinical follow-up was carried out at six months by medical visit, review of medical records or telephone contact with the patient, family or referring physician. The main outcome measured of the study was mortality or readmission at six months of follow-up. The assignment of the cause of death was based on clinical judgment of the physician taking care of the patient at the time of death.Death was deemed cardiac when it was be due to myocardial infarction, heart failure or sudden death. The incidence of reinfarction and new coronary revascularizations were also recorded.

2.3 Statistical analysis

The analysis of normal distribution of variables was performed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Quantitative variables are expressed as mean ± SD. Non-normally distributed variables are expressed as median and interquartile range.Categorical variables are expressed as number and percentage.

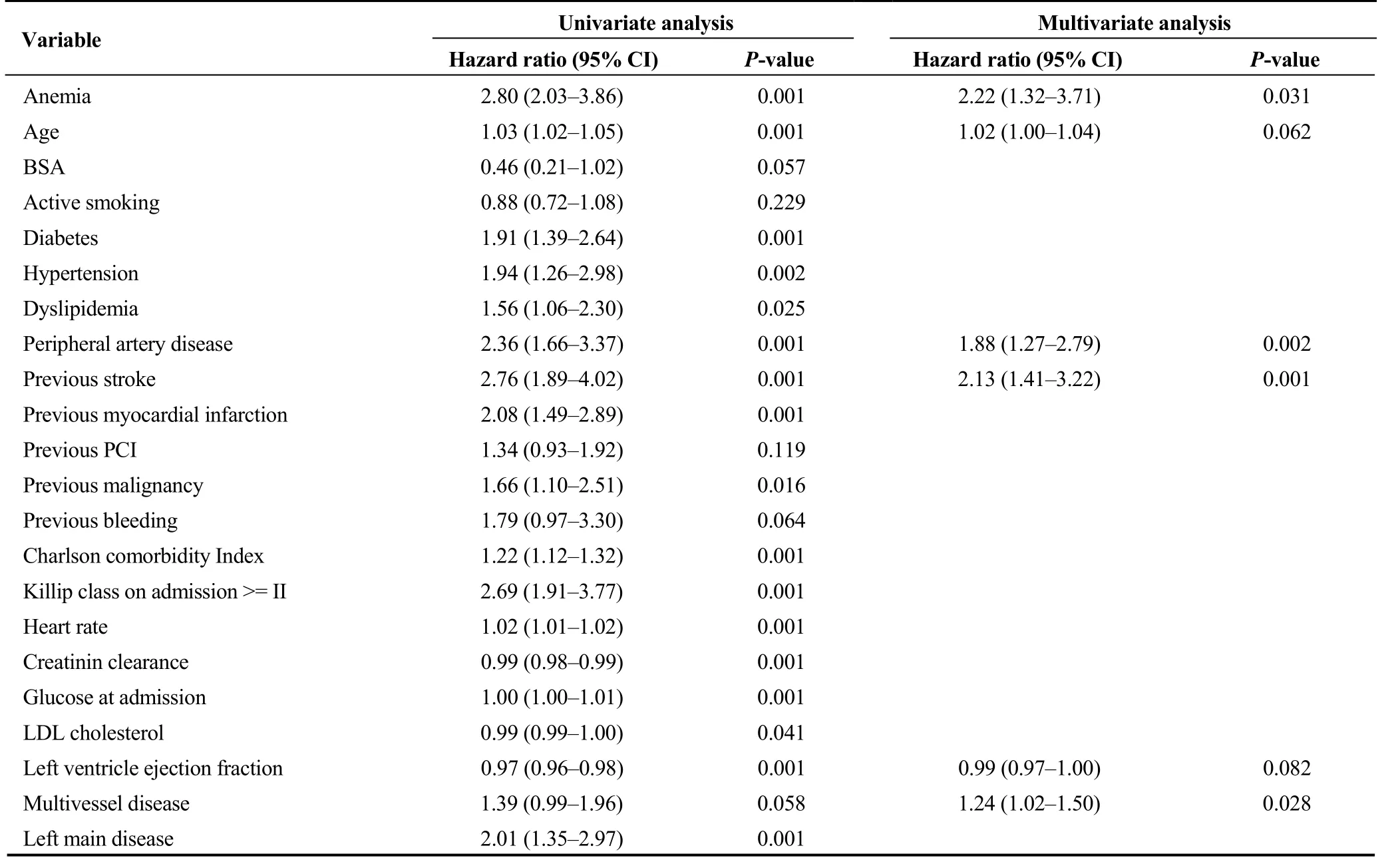

Baseline characteristics, clinical management and in-hospital clinical course were compared across if anemia was present. The association between categorical variables was analyzed with the Chi-square test, with the correction of continuity when indicated. The analysis of quantitative variables according to anemia status was performed by Student’sttest. The association between anemia and mortality or readmission at 6 months was assessed by the Cox regression method. Variables included in the multivariate analysis[14]were those with an association (P< 0.2) both with exposition (anemia) and effect (mortality or readmission at 6 months, see table), and not considered to be an intermediate variable between them.

Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan Meier curves. Statistical significance of differences was assessed by log rank test. The PASW Statistics 18 (Chicago, IL, USA)was used for all analysis.

3 Results

A total of 629 patients were included across the study period, of whom 483 (76.7%) were male. Mean age was 66.6 years.

Globally, patients from this series had a high risk profile,with a significant proportion of comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus (238/629, 37.8%), peripheral artery disease(106/629, 16.9%) or previous stroke (56/629, 8.9%). Most patients had elevated serum troponin levels (574/629,91.3%), and almost one of each five patients had signs of heart failure at admission (119/629, 18.9%). Coronary angiography during the admission was performed in the vast majority of patients (605/629, 96.2%). A total of 197 patients (31.3%) had anemia at admission.

3.1 Clinical characteristics according to anemia status

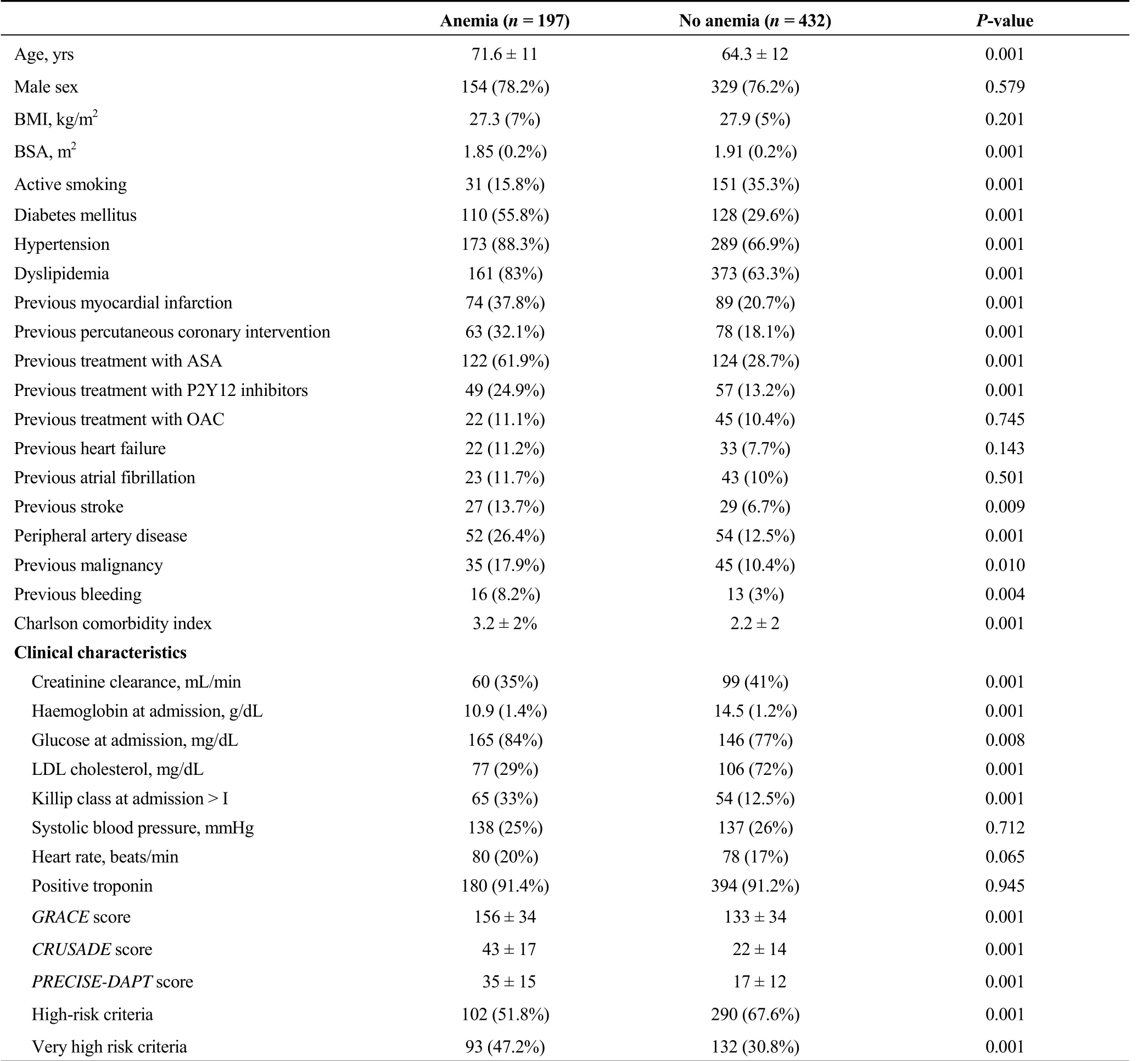

Patients with anemia were significantly older, with a higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities such as peripheral artery disease, previous stroke or previous malignancy. They also had a higher prevalence of previous myocardial infarction and higher degree of comorbidity as measured by the Charlson index (Table 1). Patientswith anemia had also poorer renal function and higher glucose levels at admission and lower levels of LDL cholesterol. These patients had higher risk criteria than the rest of patients, with a higher incidence of heart failure at admission, poorer left ventricle ejection fraction and higher GRACE, CRUSADE and PRECISE-DAPT scores values.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics according to anemia status.

3.2 In hospital clinical management and outcomes according to anemia status

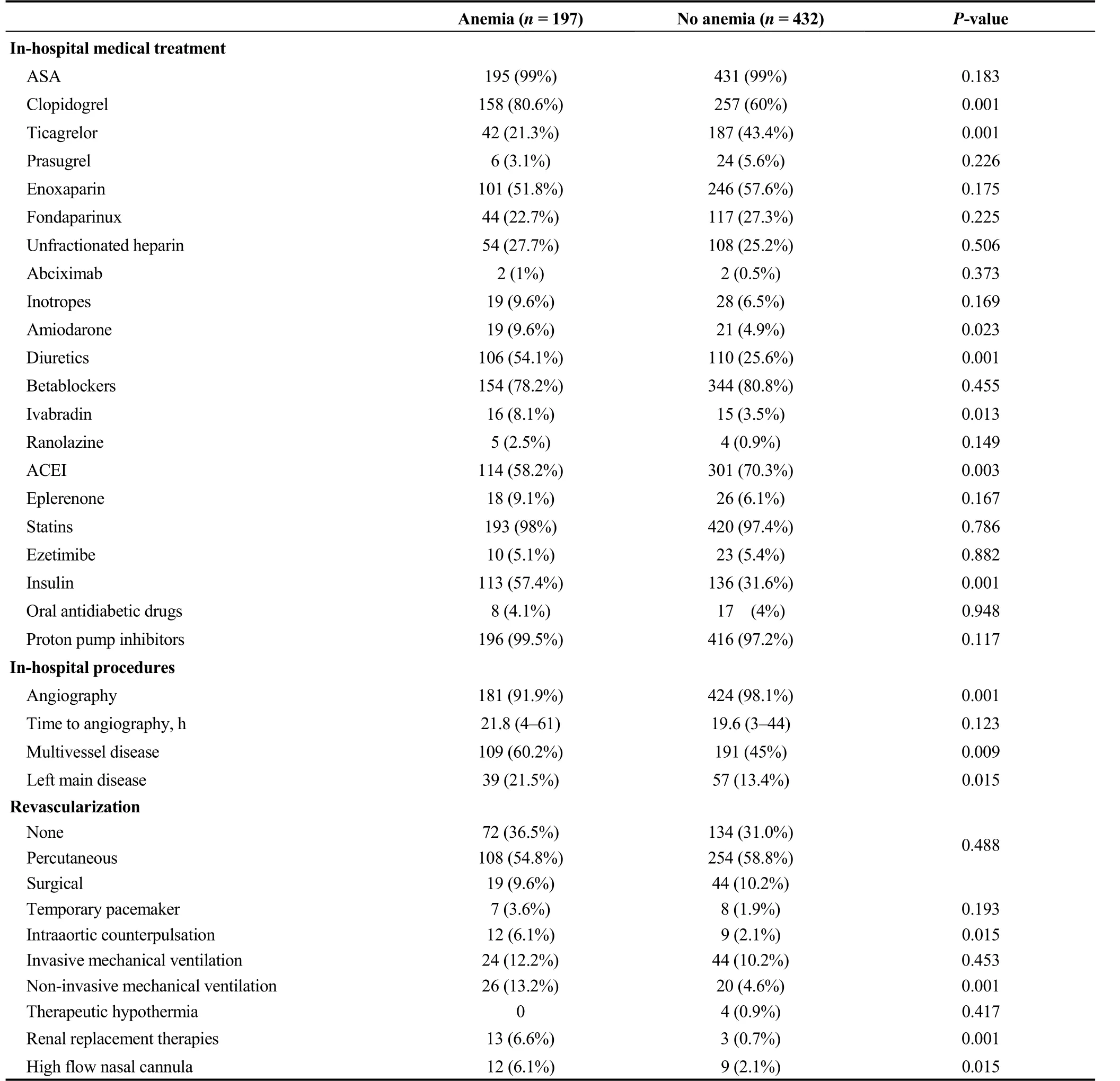

Patients with anemia underwent less often coronary angiography during the admission, with a higher proportion of multivessel disease and left main coronary stenosis, but without significant differences regarding coronary revascularization (Table 2).

Significant differences were also observed regarding in-hospital medical treatment, with a higher proportion of treatment with clopidogrel, amiodarone, diuretics and ivabradine and a lower proportion of treatment with ticagrelor and ACE inhibitors in patients with anemia. In addition,these patients underwent more often invasive in-hospitalprocedures such as intraaortic counterpulsation, non-invasive mechanical ventilation and renal replacement therapies as compared to patients without anemia.

Table 2. In-hospital management according to anemia status.

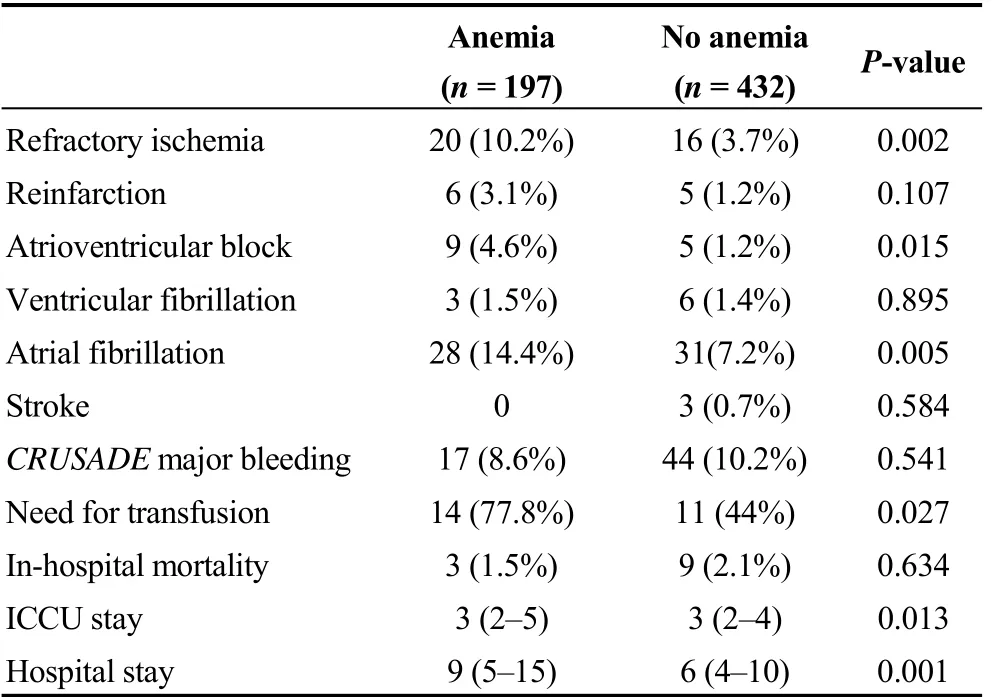

Table 3. In-hospital clinical outcomes according to anemia status.

Patients with anemia had a higher incidence of in-hospital complications such as refractory ischemia, atrioventricular block or atrial fibrillation, without differences in the rate of major bleeding or in-hospital mortality. Both ICU and in-hospital stay were significantly longer in patients with anemia (Table 3).

3.3 Post-discharge management and clinical outcomes according to anemia status

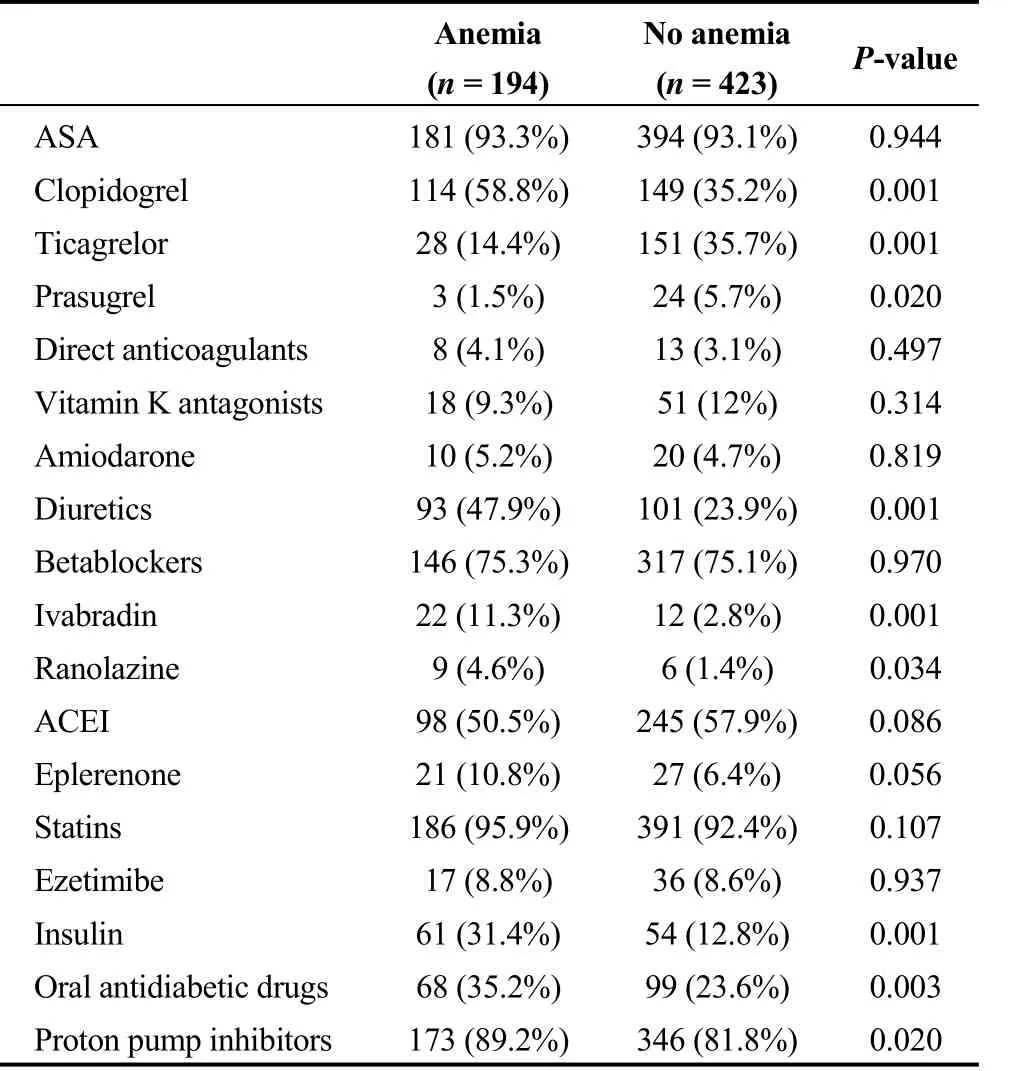

Patients with anemia were more commonly treated with clopidogrel, diuretics, ivabradine, ranolazine and proton pump inhibitors at hospital discharge (Table 4). In contrast,the rate of prescription of ticagrelor and prasugrel was significantly lower in these patients.

From 617 patients surviving at hospital discharge, data on clinical follow up was available in 586 cases (95%). Of them, 33 patients (5.6%) presented new ACS and 17 (2.9%)clinically significant bleeding at 6 months.

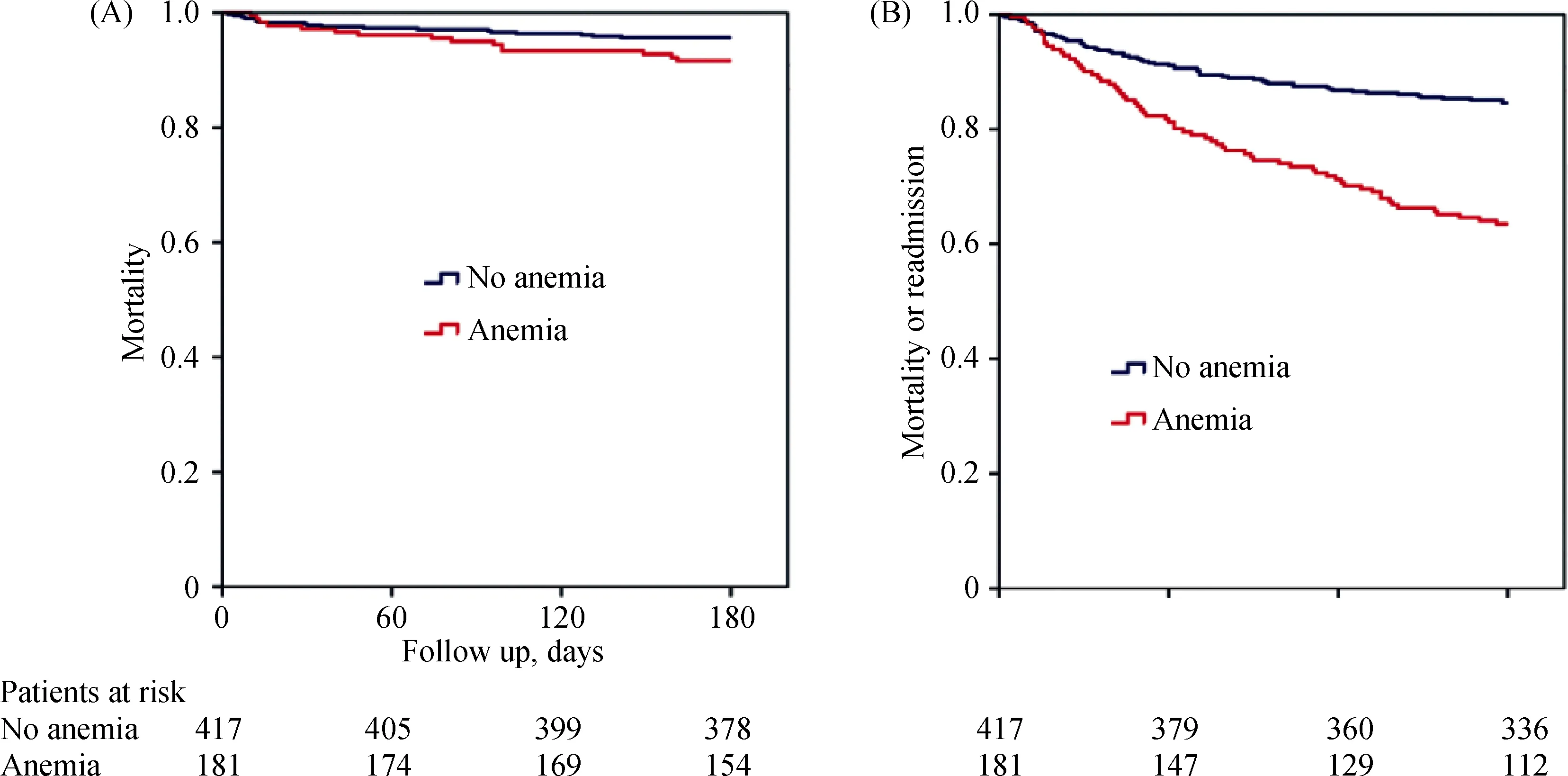

Globally, a total of 23 patients died at 6 months and 140 patients dead or were readmitted at 6 months. Both the incidence of mortality (HR = 3.36, 95% CI: 1.43-7.85,P=0.001) and the incidence of mortality or readmission were significantly higher in patients with anemia (HR = 2.80,95% CI: 2.03-3.86,P= 0.001). After adjusting for potential confounders, the association between anemia and mortality or readmission at 6 months was still significant (HR = 2.22,95% CI: 1.32-3.71,P= 0.031, Table 5). Figure 1 shows the cumulative incidence of mortality and mortality or readmission at 6 months according to anemia status.

4 Discussion

The main findings from this study are: (1) a significant proportion (31.3%) of these patients with NSTEACS had anemia at admission to ICCU; (2) patients with anemia had a significantly higher prevalence of comorbidities and higher risk criteria at admission; (3) despite the proportion was lower in patients with anemia, the vast majority of patients underwent coronary angiography during the admission (96.2%),and (4) patients with anemia had a higher incidence of mortality or readmission at 6 months, and this association was independent from potential confounders.

Anemia is a common comorbidity in ACS, and is strongly associated with poorer clinical outcomes in these patients[15-20]and also in other clinical settings.[21,22]Prevalence of anemia in patients with ACS ranges between 20%-30% in most series, and is especially higher in elderly patients with comorbidities.[23-25]In contrast, other studies including highly selected ACS patients from clinical trials[26,27]or assessing only patients treated with potent antiplatelet drugs[28]reported a significantly lower prevalence of anemia, around 10%. A not negligible proportion of patients with ACS and anemia are denied ICU admission in routine clinical practice because of a high degree of comorbidities and perception of a low life expectancy. Information aboutthe real prevalence of anemia in high-risk ACS patients admitted to critical care units is scarce. In an interesting contribution, Uscinska,et al.[6]assessed a series of 392 patients admitted to an Intensive Cardiac Care Unit between 2008-2011 (mean age, 70 ± 13.8 year). Of them, 168(42.9%) had diagnosis of ACS. The authors described a high prevalence of anemia according to WHO criteria in the whole cohort (64%), which was significantly lower in patients with ACS. Biomarkers of iron status but not anemia predicted in-hospital mortality. In another subanalysis of that series,[7]haemoglobin levels—along with age, parameters of iron status, and LVEF—were strong predictors of long-term mortality. Another small series[29]also described a high prevalence of anemia in ACS patients admitted to an ICCU. To our knowledge, no other study focused on ACS patients admitted to ICCU. Data from our study revealed that, despite being a relatively young population, almost one of each three of these high risk ACS patients admitted to ICCU had anemia at admission. This proportion is significantly lower than those observed in the series by Uscinska,et al.[6]Ours was a significantly younger homogeneous population in which we only assessed patients with NSTEACS diagnosis. On the other hand, different criteria for ICCU admission might also have contributed to the lower prevalence of anemia in our patients.

Table 4. Management at discharge according to anemia status.

Table 5. Predictors of mortality or readmission at 6 months.

Figure 1. Cumulative incidence of mortality (A) and mortality or readmission at 6 months (B) according to anemia status.

Patients with ACS and anemia are commonly managed conservatively in routine clinical practice,[4,5,23-25]with a lower likelihood of receiving potent antithrombotic drugs and undergoing coronary angiography or other intensive therapies. Therefore, little information exists about patients with high-risk ACS and anemia admitted to critical care units. In our opinion this is a crucial issue, since these patients are usually fully candidates to intensive therapies.Despite the performance of coronary angiography was less common in patients with anemia from our series, this invasive approach was selected in a high proportion of them(more than 90%). Interestingly, the performance of some ICCU procedures such as counterpulsation, non-invasive mechanical ventilation or renal replacement therapies were more common in this group, probably reflecting their higher profile of risk. In addition, a more conservative antithrombotic approach was used in patients with anemia, with a higher proportion of clopidogrel and lower of ticagrelor.Clopidogrel was the P2Y12 blocker more commonly used even in patients with normal haemoglobin values. This is also an interesting point, since recent data suggest that more antiplatelet drugs can be safely used in ACS patients with anemia with a careful assessment of ischemic and bleeding risk.[28]

Anemia was associated with a higher prevalence of comorbidities and severity of coronary disease in our patients.However, no significant differences were observed regarding the rate of revascularization according to anemia status.A potential reason for this might be the presence of more complex coronary lesions not suitable for revascularization in patients with anemia. The higher prevalence of comorbidities in patients with anemia might probably have contributed to the worse outcomes observed in these patients.However, after adjusting for potential confounders, anemia was independently associated to a higher incidence of events at follow up, as observed by Uscinska,et al.[7]In our opinion, these data support the need for a careful management and follow up in this group of complex ACS patients.

This study has some limitations, such as the moderate sample size of subgroups and the moderate number of events. It was an observational study, so we cannot rule out the presence of selection bias or residual confounding. In addition, data regarding type of anemia or iron status was not available. Finally, a longer follow up might have contributed to fully assess the association between anemia and outcomes.

Despite these limitations, in our opinion this study retrieves interesting and novel data about the real prevalence of anemia and its impact on management and prognosis of high-risk ACS patients admitted to ICCU in routine clinical practice. Improving risk stratification and outcomes in this growing group of complex patients often excluded form clinical trials might lead to important clinical and social consequences.

In conclusion, this study showed that almost one of each three patients with NSTEACS admitted to ICCU had anemia at admission. Patients with anemia had a significantly higher prevalence of comorbidities and higher risk criteria at admission, although they underwent less often coronary angiography. Anemia was independently associated to poorer outcomes in this group of high risk ACS patients undergoing a contemporary management at ICCU.

Ethics statement

All patients or their representatives signed an informed consent before being recruited for the study. Confidential information of the patients was protected according to national normative. This protocol has been approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Bellvitge University Hospital (IRB00005523).

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2020年1期

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2020年1期

- Journal of Geriatric Cardiology的其它文章

- Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia during phase II cardiac rehabilitation in a patient with heart failure: a case report

- “One-man” bailout technique for high-speed rotational atherectomy—assisted percutaneous coronary intervention in an octogenarian

- Aspergillus infection of pacemaker in an immunocompetent host: a case report

- Is dual therapy the correct strategy in frail elderly patients with atrial fibrillation and acute coronary syndrome?

- A meta-analysis of 1-year outcomes of transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in low-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis

- Prognostic factors in heart failure patients with cardiac cachexia