Efficacy of spontaneous laughter in the post-operative treatment of pain and anxiety in children: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial

Magda Ruth Pérez Cervantes, Chiharu Murata,, Volkmar Wanzke Del Angel

1 Hospital General Naval de Alta Especialidad, Mexico City, Mexico

2 Escuela Medico Naval, Mexico City, Mexico

3 Departamento de Metodología de la Investigación, Instituto Nacional de Pediatría, Mexico City, Mexico

BACKGROUND

For many years, centers have existed that provided assistance for the sick and which have been of great importance to societies. Long ago, the hospital was represented in the social imagination as a place of miraculous recovery from illness, a place where the ill and the needy could seek aid.The hospitals of New Spain were conceived as a "space of practical life which is tied to the society" (Guzmán et al.,2011). In the present day, the community is used to fewer, if any, dealings with hospitals. The role of users of the services has become passive; thus, those who are ill are considered to be patients. This view has an impact not only on the efficacy of the medical attention that is provided, but also on the quality of life of the hospitalized individuals (González and Gallardo, 2012).

Because many of the sick require prolonged and costly medical treatments, the capacity of health facilities to care for them are exceeded; this, in turn, has repercussions on the quality of the care provided, that is to say, the higher the demand, the lower the quality of the service (Guzmán et al., 2011). The World Health Organization, through the American Psychological Association, created a biopsychosocial model in which a person is thought of as a biological,psychological, and social entity, in order to optimize the quality of medical care given to the patient. This is of vital importance, as it has been proven that quality medical attention can result in earlier recovery, shorter hospital stay,and better quality of life (González and Gallardo, 2012).

The child population is no exception. Mexico is a youthful country: in 2015, 28% of the population was between 0 and 14 years of age. According to the 2014 annual report of the Hospital Infantil de México, 84.1% of this population required hospital care (INEGI, 2015).Thus, it is important to promote high-quality medical practice for this age group(INEGI, 2015).

For children, hospitalization is a contingency of life that has an impact on their perception of well-being and on the form in which they construct their reality during their stay in the hospital (Guzmán et al., 2011). It has been reported that approximately 35% of pediatric patients evidence anxiety during their stay in a hospital (Hernandez and Rabadan,2013). The child who undergoes a surgical intervention may suffer diverse psychological alterations, with 50% to 75%experiencing high levels of discomfort and stress during the hospitalization (Meisel et al., 2009).

Laughter is an expression of emotion due to various intellectual and affective elements; it is principally evinced by a series of more-or-less noisy aspirations, depending in great part on contractions of the diaphragm, which is accompanied by involuntary contractions of facial muscles and by resonance of the pharynx and soft palate (Christian et al., 2004).

More than 4,000 years ago in Imperial China, temples existed in which people gathered to laugh in order to balance their health. In India, there existed sacred temples where laughter could be practiced; some Hindu books, in discussing meditation with laughter, give assurance that an hour of laughter has effects more bene ficial to the body than four hours of yoga. In some ancient cultures, there was a figure of the "clown doctor" or "sacred clown"—a sorcerer, in distinctive dress and makeup, who exercised the therapeutic power of laughter to cure sick soldiers(Gendry, 2013).

In the middle Ages, Henri de Mondeville pointed out that cheerfulness was a de finitive tool to help patients to recuperate and that their lives should be directed toward happiness(Nasr, 2013). But, the true pioneer of laughter therapy was Rabelais who, in the XVI century, was the first doctor to apply laughter as therapy in earnest (Gendry, 2013). Battie in the 1970s, first proposed that laughter therapy be used for the mentally ill (Nasr, 2013). In 1844, Horace Wells discovered the anesthetic properties of nitrous oxide (laughing gas). Two years later, William Morton carried out the first painless surgery with nitrous oxide (Amez and Díaz, 2010).In 1964, Norman Cousins, diagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis, was treated with laughter therapy by a group of doctors; thereafter, he wrote the book, "Anatomy of an Illness as Perceived by the Patient: Re flections on Healing and Regeneration", and founded the Humor Research Task Force at UCLA Medical School (Takeda et al., 2010). In the decade of the 1970s, Dr. William Fry, a psychiatrist and the"Father of Gelotology" (science of laughter) showed that the majority of the principal physiological systems of the body are stimulated by joyous laughter.

Dr. Hunter ("Patch") Adams inspired millions by bringing diversion and joyous laughter to the hospital setting and by putting into practice the idea that "cure should be a loving human exchange, not a business transaction". In 1971, he founded the Gesundheit! Institute, a holistic medical community that provides free medical attention to this day. In 1986, Michael Christensen, director of the clowns of the Big Apple Circus of New York, was invited to give a presentation in a hospital. The result was surprising: children who were depressed and apathetic actively participated in the games. Thus was born the Clown Care Unit in the United States (Gendry, 2013).

Today, laughter therapy is used in diverse clinics and hospitals around the world as a co-adjuvant measure that favors the well-being of patients (Nasr, 2013). Laughter can lead to physiological changes in the musculoskeletal,cardiovascular, immunological, and neuroendocrine systems, all of which are associated with both short-term and long-term bene ficial effects. Various groups are studying these effects, because despite the knowledge already gained,much still remains unknown.

In 2003, Bennet et al. (2003) carried out a study of healthy women who, after having been shown humorous videos,were then evaluated for stress and immune response. It was found that the patients that had improved their mood had also improved their immune response. In 2005, Vagnoli et al. (2005) participated in a study of hospital clowns in order to reduce anxiety in children who underwent surgery, with positive results. In 2009, Middleton at al. (2009) showed signi ficant positive results in a meta-analysis that evaluated the effects of non-pharmacological interventions (hospital clowns and video games) in helping to induce anesthesia in children through the reduction of anxiety and distress.In 2010, Fernandes et al. (2010) investigated the effects of hospital clowns on the pre-operative anxiety of children scheduled for minor surgery, comparing two groups, one with intervention, the other without. The results highlighted the importance of this intervention by the clown not only for the children, but also for their parents. In 2012, Mif flin et al. (2012) recti fied the results by using the method of distraction by videos to reduce the anxiety of the children subjected to surgery. In 2013, Chang et al. (2013) carried out a study in which the psychological, immunological,and physiological effects of laughter were evaluated after the Laughing Qigong Program (LQP), a Chinese activity in which laughter is a form of meditation, had been used.They found that cortisol levels, a marker of stress, were signi ficantly lowered in those who participated in the LQP. In the same year, in order to evaluate the impact of laughter therapy on improvement of the immune system of patients with cancer, Sakai et al. (2013) measured the immunological state of patients with colorectal cancer who had undergone surgery or chemotherapy. They observed that the immunity of the patients was reduced after such cancer treatments, but that their immune state improved after laughter therapy. In a 2014 systematic review of the literature in order to determine the effect of laughter therapy on immunosuppressor hormones like oxytocin and cortisol, Michel Fari?a et al. (2014) found limited evidence and therefore called for more research in this field. In 2011, Mora-Ripoll (2011) stated that many of the existing studies contain methodological defects (such as in the lack of robustness due to ambiguity in the conceptualization of laughter (laughter vs. humor); in operation(spontaneous vs. forced laughter); and in the establishment of dosage of therapies (frequency and time)), calling for such defects to be remedied in future studies.

The objective of the current study is to determine the efficacy of laughter therapy in improving the post-operative period for children by comparing the intensity of postoperative pain among three groups: those receiving conventional treatment, those receiving conventional treatment and accompaniment without laughter, and those receiving conventional treatment and laughter therapy.

METHODS/DESIGN

Study design

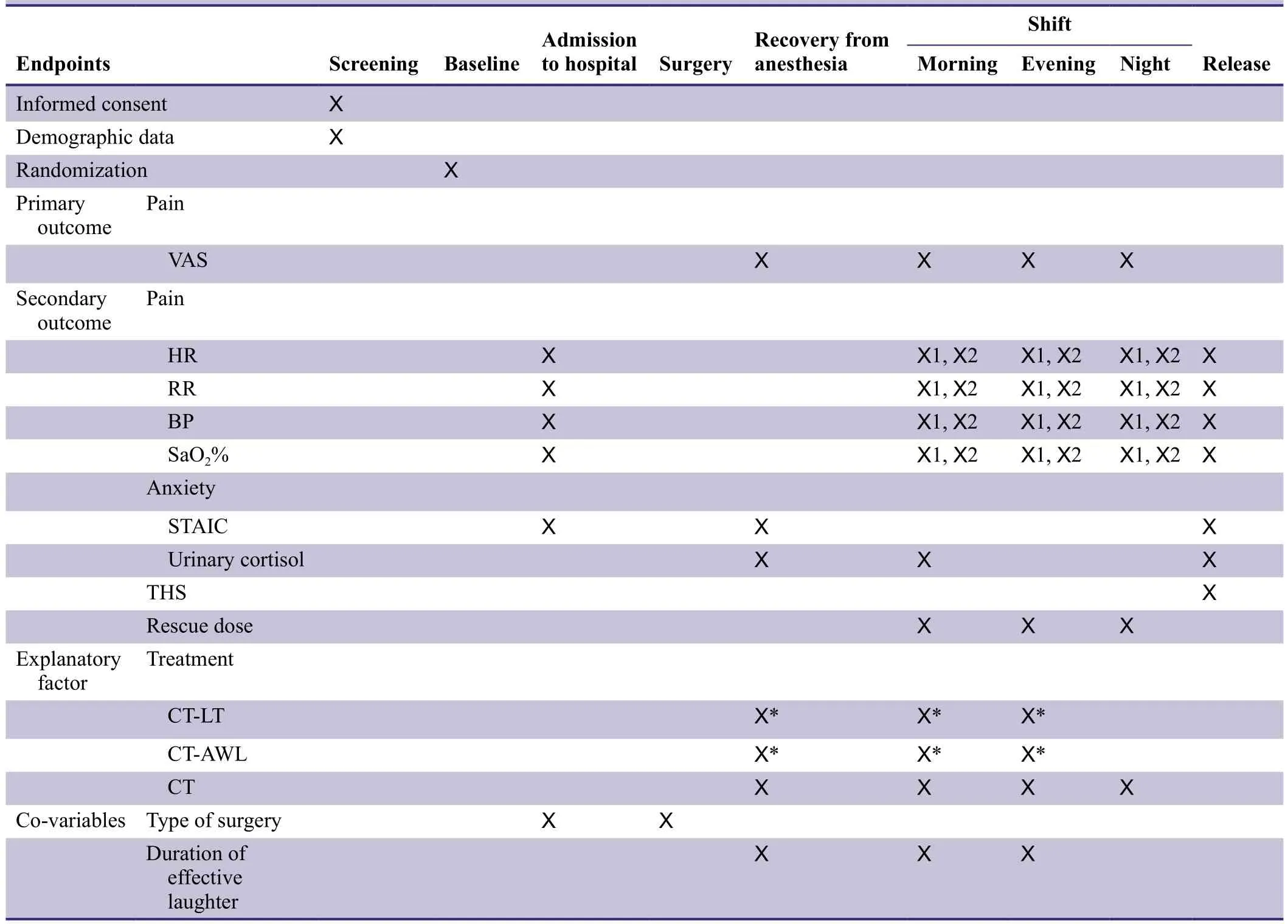

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) with three parallel arms will be carried out: CT (conventional treatment)only; CT + AWL (accompaniment without laughter); and CT + LT (laughter therapy). The treatment necessarily will be open-labelled for both the attending physician and for the patient; however, the doctor evaluating the anxiety and pain, the nursing personnel recording vital signs, and the laboratory personnel quantifying urinary cortisol levels will be blind to the assigned treatment. Included in the study are children who underwent programmed surgical intervention that showed no complication during the immediate post-operative period. After written informed consent is obtained from the parents or legal guardian(s), as well as the written assent of those children over ten years of age, the participants will be randomly assigned to one of the three groups. The interventions will be started immediately after complete recovery from anesthesia: for the CT + LT and CT + AWL groups, a 30-minute session will be provided both in the morning and in the evening until release from the hospital. For CT, pain will be managed with conventional analgesics, i.e., non-steroidal anti-in flammatory drugs(NSAIDs), at each 8-hour shift until the patient is released from the hospital (Table 1).

Study participants

Inclusion criteria

For inclusion in this study, patients must ful fill all of the following criteria: (1) pediatric patients, 6-14 years of age;(2) hospitalized for uncomplicated surgical procedures (unior bilateral hemiepiphysiodesis, removal of osteosynthesis material, osteotomy, curretage, open reduction of fractures,and minor reconstructive surgery); (3) minimum hospitalization of 48 hours; (4) written informed consent by the parents or legal guardian(s); and (5) for patients older than ten years, a letter of assent.

Exclusion criteria

Patients will be excluded from this study, if either of the following criteria is ful filled: (1) patients have endocrine pathologies, cancers, alterations of the central nervous system,or altered immune system; or (2) patients are undergoing either topical or systemic treatment with steroids. Patients that incur complications during the post-operative period will be eliminated from the study.

Table 1: Schedule of outcome assessments

Study procedure

All procedures will be carried out in the Pediatric Service of the Hospital General Naval de Alta Especialidad in Mexico City during the period from October 2015 to October 2017.Recruitment will be initiated among patients admitted to the Emergency Pediatric Service and to the Pediatric Hospital for surgery. Upon admission, evaluation according to the selection criteria will be carried out by a researcher;thereafter, during an interview, the child and the parents or legal guardian(s) will be informed of the details of the study and will be invited to participate. In the case that they accept, a written informed consent form will be obtained, as will a letter of assent, if applicable. Patients that satisfy the inclusion criteria will be randomly assigned to one of the three treatment regimens, according to the table of treatment assignment previously constructed.

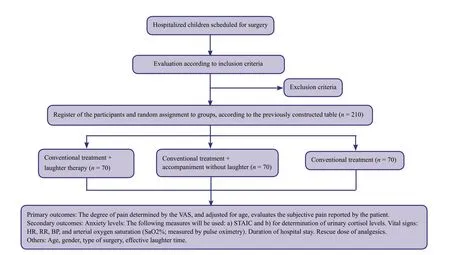

The patients in each of the three groups will be administered the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children(STAIC) to measure anxiety due to hospitalization. Pain will be evaluated by using the visual analog scale (VAS)and by monitoring of the vital signs: heart rate (HR),respiratory rate (RR), blood pressure (BP), and arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2). Comparative levels of cortisol in the urine samples from patients in the three groups will be measured. The attending surgeon for each patient will establish the time of release from the hospital, taking into account the clinical evolution of the patient, as well as the presence of post-operative complications. The data obtained will be recorded in a database created in worksheet of Microsoft Excel. See Figure 1 for a flow chart of the research procedure.

Randomization and blinding

Figure 1: Flow chart of the trial.

At the end of the evaluation of selection criteria, each patient will be consecutively assigned to a group, based on the table of randomization of treatment. In order to minimize unbalanced sample sizes among the three groups,blocks were established, the size of which is not revealed in this document. The effect of the operator carrying out the laughter therapy or the storytelling will be controlled through the use of a completely randomized block design,each operator being one block. This will be a simple blind study on the part of the evaluators of the outcomes; due to the characteristics of the treatments, it is impossible to blind either the operators (investigators) or the patients.

Interventions

CT

During the post-operative period, participants in all groups will receive conventional treatment for pain management.Medication based on NSAIDs (paracetamol, metamizol,ketorolac), as indicated by the attending surgeon, will be administered at eight-hour shifts, or in rescue doses in cases of severe pain. The time of follow-up will be a minimum of 48 hours and a maximum of 7 days. The CT group will receive no other intervention.

CT+ AWL

As a control for the effect of the experimental treatment, the second group (CT + AWL) was created. The interventions will be initiated at the time of full recovery from the anesthetics; thereafter, two interventions per day (morning and evening), each of 30-minute duration, will be administered until release from the hospital. These sessions will be carried out in the hospital's Pediatric Service by the pediatric resident on duty at the time, who will read stories and fairy tales appropriate to the age of the patients.

CT+ LT

In the CT + LT group, the interventions will be started at the time of complete recovery from the anesthetics; thereafter, two interventions per day (morning and evening),each of 30-minutes duration, will be administered until release from the hospital. These sessions will be carried out in the hospital's Pediatric Service and will be executed,in random order, by two hospital clowns (researchers) who were previously trained as such. In order to standardize the laughter therapy technique, each session will be observed by the other investigator with the end of providing feedback to the other. The sessions will consist of three phases established in the techniques of laughter therapy:1) music to establish con fidence; 2) games to promote participation by both the patients and the parents; and 3)laughter yoga to strengthen spontaneous laughter. Each session will be recorded in order to identify and monitor effective laughter.

Outcome variables and co-variables

Primary outcome variable

The degree of pain determined by the VAS, and adjusted for age, evaluates the subjective pain reported by the patient.The scale, scored 1 to 10, consists of little faces, set 1 cm apart, depicting a gradient from no pain to severe pain. This measure will be administered by the medical resident on duty at the time of recovery from anesthesia and at each 8-hour shift until release from the hospital.

Secondary outcome variables

· Anxiety levels: The following measures will be used:a) STAIC will be administered by the medical resident on duty at the time of the patient's admission to the hospital,upon recovery from the anesthetic, and before discharge from the hospital. The STAIC is a questionnaire containing 20 questions (10 positive and 10 negative), each of which is graded on a scale from 1 to 3 (none, low, high); and b) for determination of urinary cortisol levels, the nursing staff of the Pediatric Service will collect urine samples every morning during the post-operative period until release from the hospital. The samples will be analyzed in the clinical laboratory of the hospital by employing a chemoluminescence immunoassay using paramagnetic-particles (Access Cortisol Reagent).

· Vital signs: HR, RR, BP, and arterial oxygen saturation(SaO2%; measured by pulse oximetry) will be reported by nursing staff twice per shift from the patient's admission until release from the hospital.

· Duration of hospital stay: the attending surgeon will decide the time of the patient's discharge, depending on clinical improvement, management of pain, and the presence, or not, or complications. The date and time will be recorded by the investigator.

· Rescue dose of analgesics: the medical resident on duty or the attending surgeon will evaluate the necessity of administering rescue doses for each patient during the post-operative period.

Co-variables

· Age will be taken from the clinical history by the investigator

· Gender will be taken from the clinical history by the investigator

· Type of surgery

· Effective laughter time: Also known as genuine laughter, which is de fined as the expression resulting for positive emotions and associated with humor, is involuntary and contagious. Physically, contractions of the diaphragm,accompanied by repetitive syllabic vocalizations and by facial expression determined by movements of the facial muscles are observed. The resident on duty will review the videotapes of the laughter therapy sessions and will record the duration of effective laughter time for each patient.

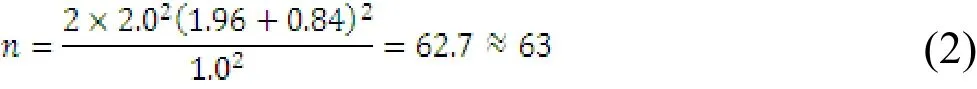

Sample size

To determine if there is a clinically important difference in the levels of pain, as determined from the VAS, between the laughter therapy group and each of the two control groups, an average effect size according to the criterion of Cohen was calculated, expecting that there would be no clinically important difference between the control groups.The sample size required was calculated by using the following formula:

where,

n: sample size

σ: standard deviation

Z1-α/2: value of corresponding to a probability of a type I error (α)

Z1-β: value of corresponding to a probability of a type II error (β)

δ: clinically relevant difference that is sought in this study It is anticipated that the values of the measure of the postoperative pain would be distributed with an average of 7.0 and a standard deviation of 2.0. Attempting to detect the difference that would correspond to 50% of the magnitude of the standard deviation, which is considered as the size of the average effect, and establishing the levels of probability of type I and type II errors as α < 0.05 and (1-β) > 0.8,respectively, the sample size calculated for each group is:

Assuming a 10% loss of data, 70 patients will be recruited for each of the three groups, giving a total of 210 patients in the study.

Statistical analysis

Prior to the estimation of the effect of the treatments on the proposed outcome variables, the distributions of the demographic, clinical, and psychological data among the three established groups will be compared. Following this comparison, the result of the analysis will be reported,without adjustment, and will be submitted to separate comparisons between the groups of outcome variables. The calculated sample size, 70 patients per group, should permit the distribution of the estimates to be compatible with the normal model based on the central limit theorem; therefore,comparison by using one-way analysis of variance will be carried out. In all the statistical analyses, the principal effect will be considered to be statistically signi ficant at a level of P < 0.05. In the procedure for the selection of variables in the construction of the statistical model, the variables whose results in the statistical test are P < 0.20 will be included;the end of the interaction will be considered signi ficant at the level of P < 0.10. Data will be analyzed by using the commercial statistical package JMP 8 (SAS Institute).

DISCUSSION

Various studies have attempted to generate evidence of the ef ficacy of laughter therapy in the search for a better prognosis for the patient. We de fine laughter therapy as the therapy that provokes laughter, the effect of this is based on the physiological reaction, organized and regulated by the limbic system and brain stem, not in the management of emotions. Previous research have studied the positive effects: reduced anxiety and stress, improved immune response, reduced in flammatory process, and increased tolerance to pain. However, many of such studies have been described as having methodological problems.

To our knowledge, there has not been an RCT to determine the effect of laughter therapy which controls the effect of the vehicle, that is, the effect of the presence of the person that implements the laughter therapy. In the current study,this potential confounding factor is controlled by establishing a control group CT + AWL. Also, in the present study,both subjective (self-reported questionnaires) and objective measurements (urinary cortisol levels) of pain will be used.As a co-variable, the effective time of the laughter will provide more robustness to this study.

Trial status

Ongoing and recruiting at the time of submission.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Author contributions

MRPC and CM conceive and design the protocols, write and revise the paper, and VWDA participate in trial design and conduction. All authors approve the final version of the paper.

Plagiarism check

This paper was screened twice using CrossCheck to verify originality before publication.

Peer review

This paper was double-blinded and stringently reviewed by international expert reviewers.

Amez AJ, Díaz PM (2010) Pain management in pediatric odontology. Rev Estomatol Herediana 20:166-171.

Bennett MP, Zeller JM, Rosenberg L, McCann J (2003) The effect of mirthful laughter on stress and natural killer cell activity. Altern Ther Health Med 9:38-45.

Chang C, Tsai G, Hsieh CJ (2013) Psychological, immunological and physiological effects of a Laughing Qigong Program (LQP)on adolescents. Complement Ther Med 21:660-668.

Christian R, Ramos J, Susanibar C, Balarezo G (2004) Laugh therapy: a new field for healthcare professionals. Rev Soc Per Med Inter 7:57-64.

Fernandes SC, Arriaga P (2010) The effects of clown intervention on worries and emotional responses in children undergoing surgery. J Health Psychol 15:405-415.

Gendry S (2013) Certi fied Laughter Yoga Teacher Workbook.American School of Laughter Yoga.

González ML, Gallardo DE (2012) Quality of medical attention: the difference between life and death. Revista digital universitaria UNAM 13:8-10.

Guzmán SV, Torres HJ, Plascencia HA, Castellanos MJ, Quintanilla MR (2011) Hospital culture and the narrative process in the sick child. Estudio sobre las culturas contemporáneas, época II. XVII:23-44.

Hernandez PE, Rabadan RJ (2013) Hospitalization, a break in the child's life. Educational attention in infantile hospitalized population. Perspectiva Educacional 52:167-181.

INEGI (2015) Mujeres y hombres en México 2014. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, México.

Meisel V, Chellew K, Ponsell E, Ferreira A, Bordas L, García BG(2009)The effect of hospital clowns on the psychological discomfort and the maladjusted behavior of boys and girls undergoing minor surgery. Psicothema 21:604-609.

Mif flin KA, Hackmann T, Chorney JM (2012) Streamed video clips to reduce anxiety in children. Anesth Analg 115:1162-1167.

Mora-Ripoll R (2011) Potential health bene fits of simulated laughter: A narrative review of the literature and recommendations for future research. Complement Ther Med 19:170-177.

Nasr SJ (2013) No laughing matter: laughter is good psychiatric medicine. A case report. Curr Psychiatr 12:20-25.

Sakai Y, Takayanagi K, Ohno M, Inose R, Fujiwara H (2013) A trial of improvement of immunity in cancer patients by laughter therapy. Jpn Hosp 32:53-59.

Takeda M, Hashimoto R, Kudo T, Okochi M, Tagami S, Morihara T, Sadick G, Tanaka T (2010) Laughter and humor as complementary and alternative medicines for dementia patients. BMC Complement Altern Med 10:28.

Vagnoli L, Caprilli S, Robiglio A, Messeri A (2005) Clown doctors as a treatment for preoperative anxiety in children: a randomized,prospective study. Pediatrics 116:563-567.

Woodbury-Fari?a MA, Antongiorgi JL (2014) Humor. Psychiatr Clin N Am 37:561-578.

Yip P, Middleton P, Cyna AM, Carlyle AV (2009) Non-pharmacological interventions for assisting the induction of anaesthesia in children. Syst Rev CD006447.

Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Trials:Nervous System Diseases2016年3期

Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Trials:Nervous System Diseases2016年3期

- Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Trials:Nervous System Diseases的其它文章

- Evaluation of cardiac autonomic status using QTc interval in patients with leprosy

- Effect of pre-incisional anterior scalp block on intraoperative opioid consumption in adult patients undergoing elective craniotomy to remove tumor: study protocol for a randomized double-blind trial

- Effects of lung protective ventilation on pulmonary function,inflammation, and oxidative stress in patients undergoing craniotomy: study protocol for a multi-center, randomized,parallel, controlled trial

- Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on white matter fibers of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder as assessed by diffusion tensor imaging: study protocol for a parallel group,controlled trial

- Migraine prevention by noninvasive electrical fastigial nucleus stimulation: a multi-center, randomized, double-blind,sham-controlled trial

- Scalp acupuncture twisting manipulation for treatment of hemiplegia after acute ischemic stroke in patients: study protocol for a randomized, parallel, controlled, single-blind trial