Evaluation of Risk Factors for Arytenoid Dislocation after Endotracheal Intubation: a Retrospective Case-control Study

Le Shen, Wu-tao Wang, Xue-rong Yu, Xiu-hua Zhang*, and Yu-guang Huang*

1Department of Anesthesiology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China

2Department of Anesthesiology, Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Medical University, Xi’an 710077, China

ARYTENOID dislocation is a rare clinical complication after endotracheal intubation.1Common symptoms of this condition include hoarseness, breathy voice, and dysphagia.2The causes include the use of laryngeal mask airway.3The incidence of this complication is estimated to be 0.1%,4yet there is no systematic study on the incidence. In addition, few studies have showed any definite or possible risk factors associated with arytenoid dislocation. To identify the potential risk factors associated with postoperative arytenoid dislocation. We conducted this retrospective matched case-control study, taking into account possible variables, such as patients’ demographic characteristics, preoperative conditions, anesthesia and surgical procedures, aiming to indentify possible risk factors for postoperative arytenoid dislocation.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients and data collection

The protocol was approved by the institutional human investigation committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH). From September 2003 to August 2013, altogether sixteen cases of postoperative arytenoid dislocation were reported in PUMCH. For each case of postoperative arytenoid dislocation, one patient matched in date and type of anesthetic and surgical procedures was chosen as the control. Medical records of all the patients and controls were reviewed.

All the patients of both groups were monitored with electrocardiography, non-invasive arterial pressure, pulse oximetry, and capnography in operating room. Recorded data of all the patients were compared, including demographics, smoking and drinking status, preoperative physical status, airway evaluation, intubation procedures, preoperative laboratory test results, anesthetic use and intensive care unit (ICU) stay. For arytenoid dislocation cases, we further analyzed the proportions of left and right arytenoid dislocation, and the outcomes of surgical repair and conservative treatment. All the arytenoid dislocation cases were examined and diagnosed by vocal cord specialists using video laryngo-stroboscopy.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages, and were compared using the Chi-squared test. Continuous variables were expressed as means±SD and compared using the Student’s unpaired t-test. To determine the predictors of arytenoid dislocation, a logistic regression model was used for multivariate analysis. All reported P-values were two-sided, and P<0.05 was considered to indicate statis- tical significance.

RESULTS

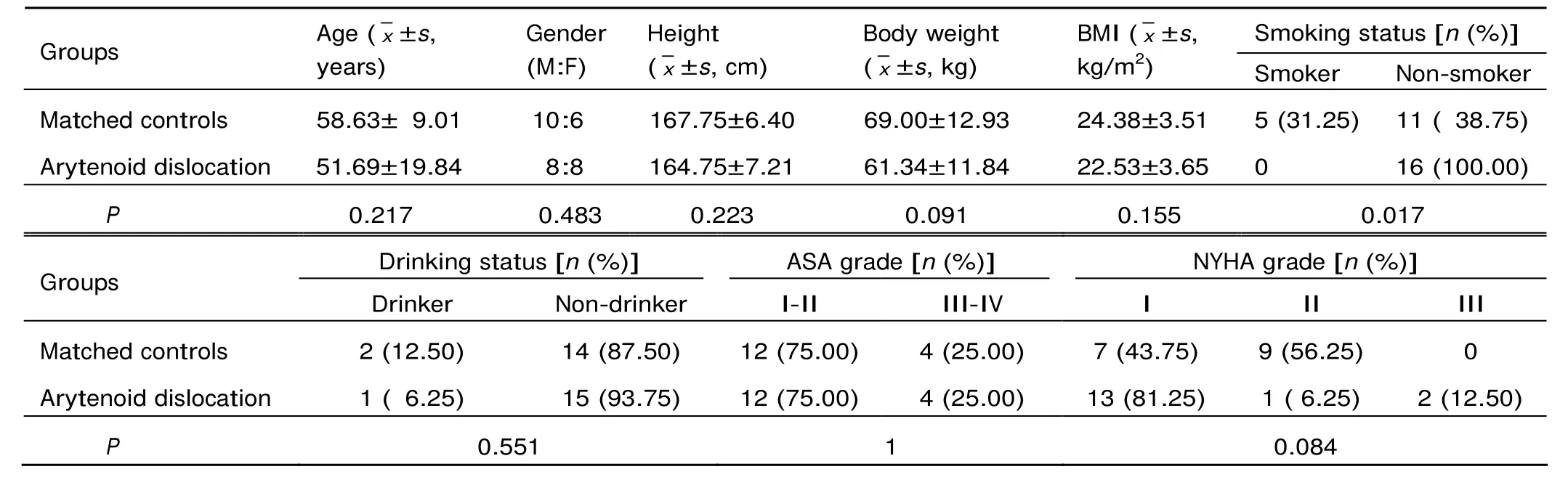

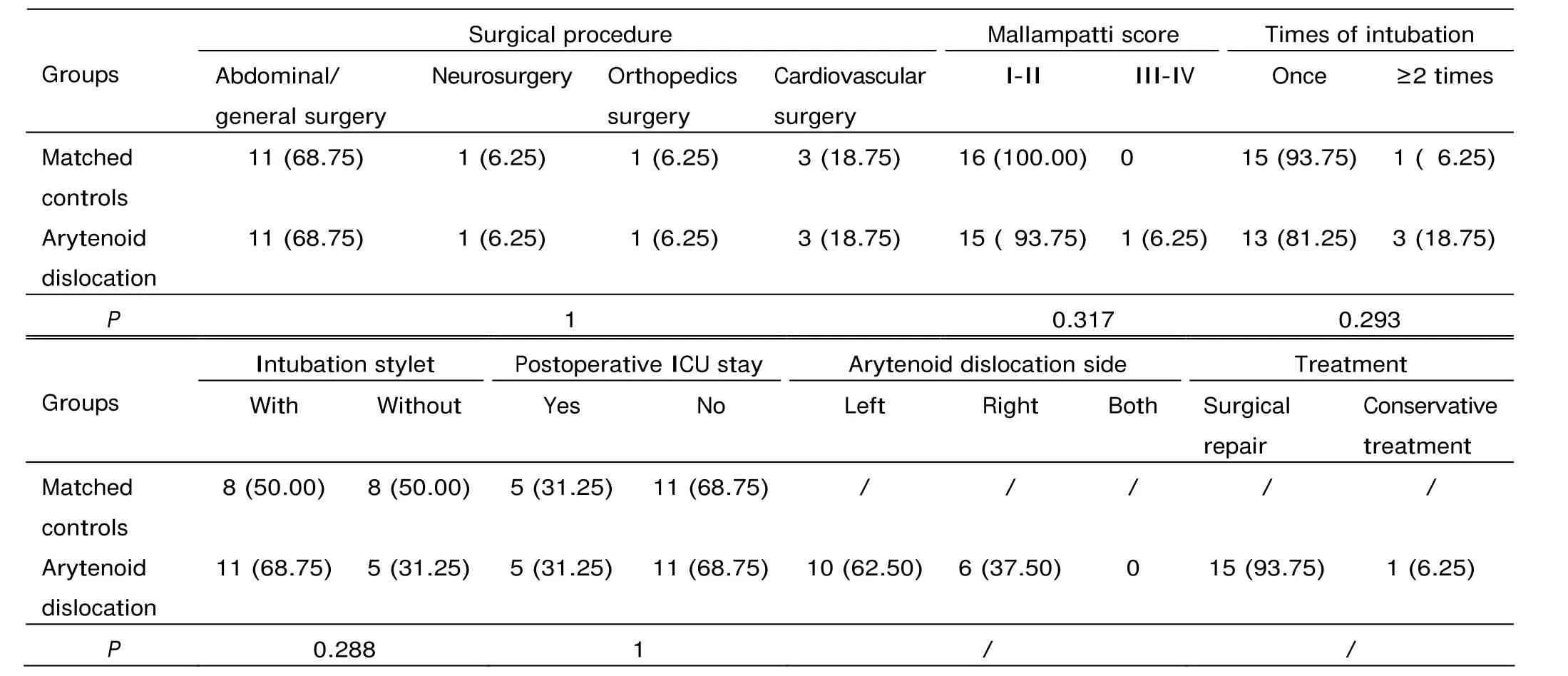

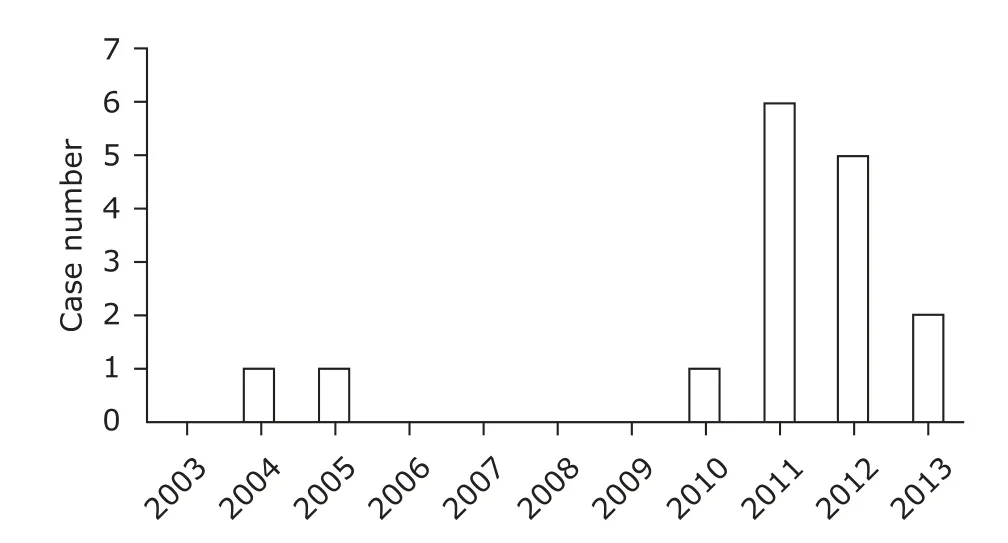

Sixteen patients demonstrating postoperative arytenoid dislocation (eight women and eight men) were included, with a mean age of 52±20 years. The arytenoid dislocations cases and the controls were matched in the demographic indexes, except for the smoking status. None of the postoperative arytenoid dislocation cases were smokers, in comparison to the existence of five smokers in the control group (P=0.017, Table 1). Ten patients (62.50%) had left arytenoid dislocation and six (37.50%) had right arytenoid dislocation (Table 2). Most postoperative arytenoid dislocation patients (15/16, 93.75%) received surgical repair, except one who recovered after conservative treatment (Table 2). Meanwhile, most postoperative arytenoid dislocation cases were reported in the years from 2011 to 2013 (13/16, 81.25%, Fig. 1).

Table 1. Demographics of arytenoid dislocation cases versus matched controls (both n=16)

Table 2. Surgical and anesthesia procedures of arytenoid dislocation cases versus matched controls [both n=16, n (%)]

Figure 1. Arytenoid dislocation cases reported from 2003 to 2013.

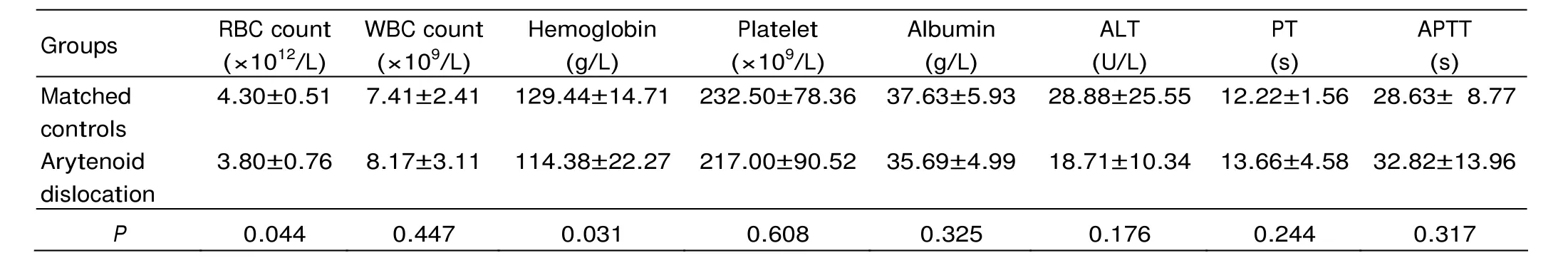

Of the laboratory test results, red blood cell (P=0.044) and hemoglobin (P=0.031) levels were significantly lower in arytenoid dislocation cases than in matched controls (Table 3). However, logistic regression analysis showed that neither non-smoking (P=0.999) nor low red blood cell/hemoglobin level (P=0.053) was an independent risk factor for postoperative arytenoid dislocation. Neither intubation procedure nor ICU stay had influence on the incidence of postoperative arytenoid dislocation.

DISCUSSION

The average number of patients who received general anesthesia with intubation at PUMCH was 20 000 to 25 000 per year. We found that arytenoid dislocation occurred at a very low rate, less than 0.01%, in patients receiving tracheal intubation over the past 10 years in our hospital. The incidence of postoperative arytenoid dislocation in our study population is similar to another retrospective survey1which found 4 cases of this complication in 13 698 intubation cases (0.029%) over a 3-year period, but extremely lower than another previous report that found one arytenoid cartilage dislocation in 1000 direct laryngoscopic intubations.4We routinely chose the tracheal tube with internal diameter of 7.5 mm for men and that with internal diameter of 7.0 mm for women, and the use of tubes with smaller diameters may reduce the risk of arytenoid dislocation after anesthesia.5

Our data showed that smokers’ proportion, red blood cell count and hemoglobin levels were significant lower inthe arytenoid dislocation group than in the control group. Smoking always induces chronic cough, expectoration and pharyngitis,6which might cause chronic inflammatory infiltration and stabilize arytenoid joint. In contrast, anemia might result in unstable or fragile arytenoid joint that is susceptible to dislocation. Our results also suggest that body weight (P=0.091) and New York Heart Association grade (P=0.084) might be factors associated with the occurrence of postoperative arytenoid dislocation, which means slimmer but stronger patients might be more susceptible. However, no statistical significance was found between the arytenoid dislocation group and the control group in terms of these two factors.

Table 3. Laboratory test results of arytenoid dislocation cases versus matched controls (both n=16, x ±s)

Most postoperative arytenoid dislocation cases in this study were reported from the year 2011 to 2013, a fact presumably attributed to two reasons. Firstly, since 2011 several types of video-assisted laryngoscopes have been applied for intubation in our hospital. These techniques could improve the view of vocal cord significantly, and thereby facilitating the procedure of intubation. Secondly, the adverse event reporting system was implemented in our hospital in the year 2010. From then on, postoperative arytenoid dislocation, on the list of adverse events, must be reported to both the Department of Anesthesiology and the Department of Medical Affairs, assuring that no case of postoperative arytenoid dislocation was missed. The reporting system raised the attention to postoperative arytenoid dislocation in anesthesiologists, and increased the officially reported incidence of this complication as a by-effect.

This study has some limitations. Patients enrolment was dependent on the medical records, primarily the discharge diagnosis of all the medical records in the past 10 years. However, not all the patients complicated with postoperative arytenoid dislocation were diagnosed before discharge, which might partially explain the low incidence of arytenoid dislocation in this study. A larger prospective study is necessary to define more precisely the incidence of this complication. The second limitation is the nature of this study being a retrospective case-control study. There is most likely some degree of selection bias, and the sample size is only 16 in either group. These limitations reduced the effectiveness of statistical analysis. Risk factors such as ICU stay7and intubation times8that previously reported as associated with postoperative hoarseness and arytenoid dislocation showed no statistical significance in this study. A multicenter study with enrolment from more hospitals may lead to more reliable results.

In conclusion, the incidence of postoperative arytenoid dislocation was lower than 0.01% in patients receiving endotracheal intubation in this study. Non-smoking and anemic patients might be susceptible to postoperative arytenoid dislocation; however, neither of the factors was an independent risk factor for postoperative arytenoid dislocation.

1. Szigeti CL, Baeuerle JJ, Mongan PD. Arytenoid dislocation with lighted stylet intubation: case report and retrospective review. Anesth Analg 1994; 78: 185-6.

2. Rubin AD, Hawkshaw MJ, Moyer CA, et al. Arytenoid cartilage dislocation: a 20-year experience. J Voice 2005; 19: 687-701.

3. Rosenberg MK, Rontal E, Rontal M, et al. Arytenoid cartilage dislocation caused by a laryngeal mask airway treated with chemical splinting. Anesth Analg 1996; 83: 1335-6.

4. Yamanaka H, Hayashi Y, Watanabe Y, et al. Prolonged hoarseness and arytenoid cartilage dislocation after tracheal intubation. Br J Anaesth 2009; 103: 452-5.

5. Mikuni I, Suzuki A, Takahata O, et al. Arytenoid cartilage dislocation caused by a double-lumen endobronchial tube. Br J Anaesth 2006; 96: 136-8.

6. Rigotti NA. Smoking cessation in patients with respiratory disease: existing treatments and future directions. Lancet Respir Med 2013; 1: 241-50.

7. Niwa Y, Nakae A, Ogawa M, et al. Arytenoid dislocation after cardiac surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2007; 51: 1397-400.

8. Tan V, Seevanayagam S. Arytenoid subluxation after a difficult intubation treated successfully with voice therapy. Anaesth Intensive Care 2009; 37: 843-6.

Chinese Medical Sciences Journal2014年4期

Chinese Medical Sciences Journal2014年4期

- Chinese Medical Sciences Journal的其它文章

- Inhibition of Xanthine Oxidase Activity by Gnaphalium Affine Extract

- Non-enhanced Low-tube-voltage High-pitch Dual-source Computed Tomography with Sinogram Affirmed Iterative Reconstruction Algorithm of the Abdomen and Pelvis

- Primary Combined Intra-articular and Extra-articular Synovial Osteochondromatosis of Shoulder: a Case Report

- Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Small Intestine: a Case Report△

- BRAF V600E Mutation as a Predictive Factor of Anti-EGFR Monoclonal Antibodies Therapeutic Effects in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: a Meta-analysis

- Multiple Myeloma Mimicking Spondyloarthritis: a Case Report