BRAF V600E Mutation as a Predictive Factor of Anti-EGFR Monoclonal Antibodies Therapeutic Effects in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: a Meta-analysis

Qi Wang, Wei-guo Hu, Qi-bin Song, and Jia Wei

Department of Oncology, Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan 430060, China

COLORECTAL cancer is one of the commonest human malignancies and the leading causes of cancer related-death in western countries, accounting for approximately 9% of all cancer incidence and mortality.1Although early diagnosis and timely operation may benefit patients and result in an almost complete healing, about 25% of newly diagnosed patients were metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC), of whom 5-year survival is approximately 11%.2Meanwhile, about up to 40%-50% of patients with surgical resection will develop metastases and die of this condition.3Despite of this harsh circumstance, the clinical applications of combination and sequential chemotherapy of irinotecan, oxaliplatin, capecitabine and fluorouracil have prolonged survival of mCRC patients drastically. However, the efficacy of chemotherapy has reached a plateau. The introduction of new active cytotoxic agents, such as irinotecan and oxaliplatin, does not improve long-term survival of mCRC patients. The recurrence rate for patients resected III/IV disease still remains at above 20%.4,5

Monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs) targeting epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) provides new options for clinical treatment. The combination of targeted biological agents with chemotherapy has increased the overall median survival of mCRC patients. Van Cutsem et al6demonstrated anti-EGFR MoAb combined with FOLFIRI could improve progression-free survival (PFS) compared with FOLFIRI alone. The meta-analysis by Zhang et al7also suggested that combination treatment of anti-EGFR MoAb and chemotherapy was associated with significantly increased response rate and longer PFS in mCRC patients. Proper use of these targeted agents can have a major impact on the patients’ prognoses.

Cetuximab and panitumumab are both MoAbs that inactivate the extracellular domain of EGFR and have been approved for the treatment of chemotherapy-resistant mCRC. These costly and toxic agents are effective in only a small percentage of patients.8,9In order to select the mCRC patients that are most likely to profit from anti-EGFR MoAbs treatment, there is a certain need to search for biologic predictive markers that will assist clinicians in making decisions.

KRAS mutation is the first established molecular marker which impedes responsiveness to anti-EGFR MoAbs treatment. Given the high negative predictive value (99%) of the KRAS mutation,10genetic testing of KRAS to screen patients who are more likely to gain clinical benefits will prevent drug toxicity and lighten the financial burden. However, only one third of patients carrying wild-type (WT) KRAS will respond to anti-EGFR MoAbs, implying that there may be other predictive markers determining clinical efficacy of anti-EGFR MoAbs for mCRC.

The members of EGFR downstream signaling pathways, including the RAS-RAF-MAPK and PI3K-PTEN-AKT signaling pathways, may be associated with resistance to anti-EGFR therapy. BRAF is the key mediator of EGFR signaling and BRAF mutations have been proved to be related with poor clinical outcomes. The best described and most studied BRAF mutation in tumors is the V600E mutation, a thymidine-to-adenine mutation which leads to substitution of valine with glutamate at codon 600.11A number of studies have explored the relation between BRAF V600E mutation and responsiveness to anti-EGFR MoAbs. Di Nicolantonio et al12reported negative interference of BRAF mutation with the clinical benefits of mCRC patients who received anti-EGFR MoAbs. None of the patients with BRAF mutation responded to targeted therapy, in contrast, all responders carried WT BRAF. In Loupakis et al13, patients with WT KRAS/WT BRAF were not associated with improvements in PFS and overall survival (OS) when they received combination therapy of anti-EGFR MoAbs and chemotherapy. A pooled analysis of the CRYSTAL and OPUS randomized clinical trials indicated that patients with WT BRAF achieved benefits in OS from addition of cetuximab to chemotherapy, although it did not reach statistical significance in objective response rate (ORR) and PFS.14Although various studies have investigated BRAF V600E and therapeutic effects of anti-EGFR MoAbs, the results still remain controversial. Therefore, we conducted this meta-analysis to pool available data, as an attempt to conclude a definite estimation of the value of BRAF V600E mutations in predicting the efficacy of anti-EGFR MoAbs in treating mCRC patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Publication search

Systematic searches in PubMed and EMBASE (up to June 4, 2013) were performed without language restriction, using the terms “metastatic rectal cancer”, “metastatic colon cancer”, “metastatic colorectal cancer”, “mCRC”, “BRAF”, “cetuximab’’, “panitumumab”, “monoclonal antibodies”, and “MoAb”. The search was limited to human studies. All eligible studies were retrieved, and their bibliographies were checked for other relevant publications. When the same patient population was used in several publications, only the latest, largest or most complete study was included in this meta-analysis.

The included studies have to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) exploring the relationship between BRAF mutation status and response to anti-EGFR MoAbs in mCRC patients; (2) reporting ORR, PFS and OS; (3) with full texts available. Exclusion criteria included: (1) reviews, tutorials and letters; (2) not case-control studies; (3) animal studies; (4) reporting insufficient data as number of cases and controls, no genotype data; (5) duplicate data.

Data extraction

From each of the eligible studies, the following data were collected: first author’s name, year of publication, amount of patients screened, study designs, study treatment protocols, response criteria, amount of patients in each BRAF mutations status, line of treatment, and outcomes (ORR, PFS and OS). The clinical endpoints were extracted separately according to BRAF mutation status if possible as well as KRAS mutation status. Data extraction was done independently by two authors of this paper. Disagreements were resolved through discussion between them. If they could not reach a conclusion, another author was consulted to resolve the divergence and a final decision would be made by majority votes.

Statistical analysis

All the statistical tests in this meta-analysis were performed with RevMan 5.4 and STATA version 10.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). The primary endpoints were ORR, PFS and OS. The association between BRAF mutations in WT KRAS patients and ORR was expressed as an odds ratio (OR), namely the ORR in mutant BRAF/WT KRAS patients divided by that in WT BRAF/WT KRAS patients. The association between BRAF mutations and PFS or OS was expressed as a hazard ratio (HR). For those trials that did not provide this information, data were extracted from published survival curves where available to estimate the values of the log HR and variance according to previously described methods.15A HR >1 indicates a deterioration in PFS and OS for mutant BRAF compared with WT BRAF.

Heterogeneity was checked using the Q-test.16,17If significant heterogeneity was found to be less than 0.10, the random-effects model instead of the fixed-effects model was used for further analysis. The amount of heterogeneity was estimated using the I2statistic,16I2>50% indicating the existence of a substantial heterogeneity, and I2<75% meaning that the heterogeneity could be accepted. A Galbraith plot was used to assess heterogeneity between studies.18Heterogeneity was also explored using logistic meta-regression analysis with the following study characteristics: ethnicity, treatment protocol (fluorouracil- based chemotherapy, capecitabine-based chemotherapy), line of treatment (first-line treatment, second- or later-line treatments). Egger’s linear regression test19was used to assess publication bias. All P values were two-tailed with a significant level at 0.05.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the included studies

After comprehensive searching, 12 articles met the inclusion criteria. However, the study reported by Laurent-Puig et al20, Sartore-Bianchi et al21and Di Nicolantonio et al12were excluded because the cases overlapped with the samples in researches by De Roock et al22. The studies by Fornaro et al23and Souglakos et al24were also excluded for using duplicative cases with Loupakis et al13and Saridaki et al25respectively.

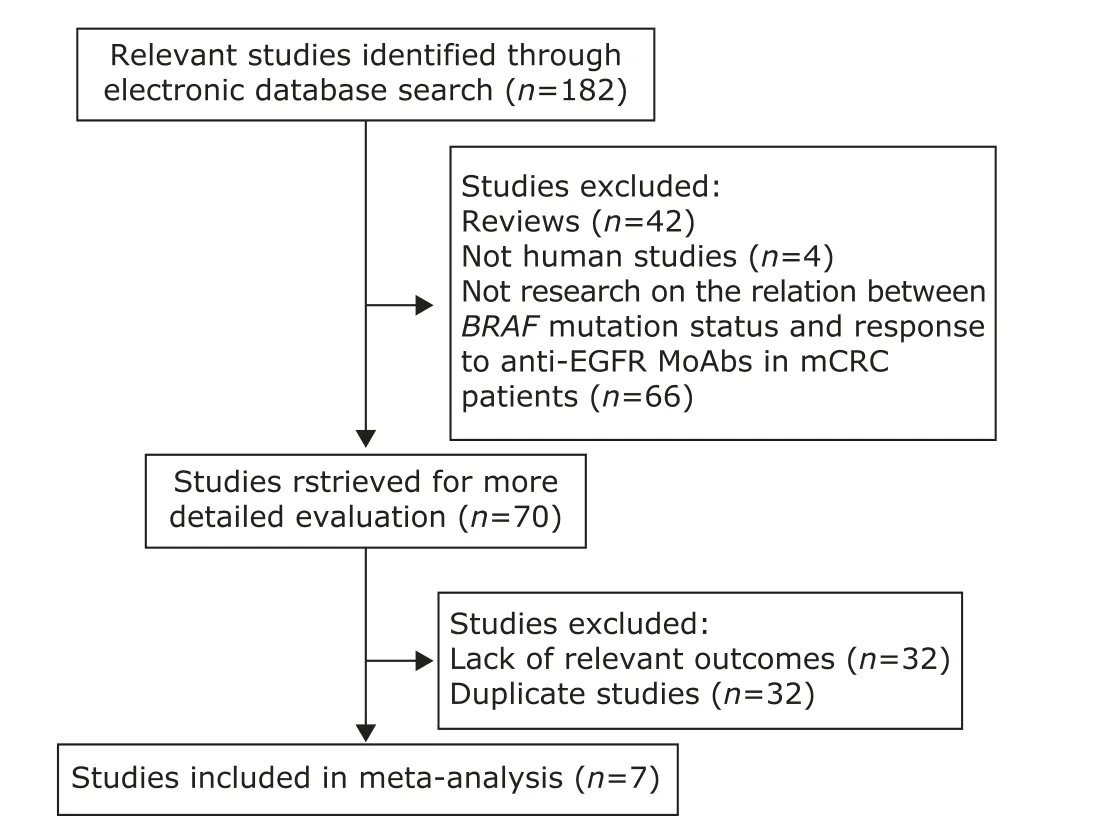

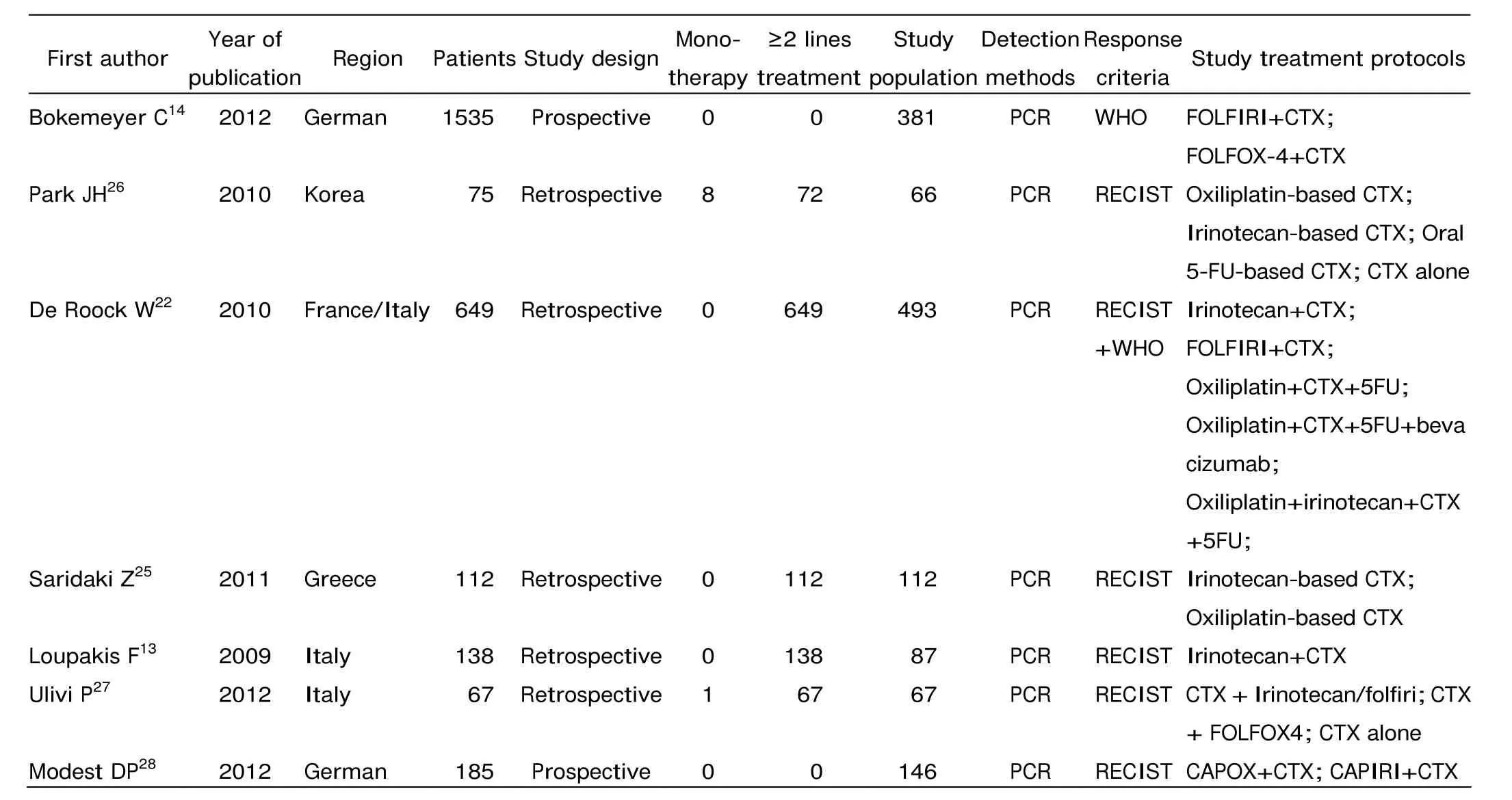

After exclusion of duplicate and irrelevant studies (Fig. 1), 7 studies13,14,22,25-28were included in this meta- analysis. Table 1 shows the primary characteristics of the 7 studies in patients treated with anti-EGFR MoAbs, 2 of which were prospective studies, the other 5 were retrospective studies. The 7 studies included a total of 1352 patients, with sample sizes ranging from 67 to 493. Most of the patients received a cetuximab-based therapy as second- or later-line therapy after chemotherapy failure. We considered the study by Park et al26as second- or later-line therapy because 96% of the patients they recruited received cetuximab-based chemotherapy as second- or later-line treatment. The detailed treatment protocols in those studies are shown in Table 1. Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumor (RECIST) or WHO criteria were used to classify tumor response in all the studies.

BRAF mutations and PFS in unselected mCRC patients

Three studies22,25,27were performed in unselected mCRC patients. BRAF mutation was associated with worse survival (HR=3.66, 95% CI=2.58-5.20). There was no significant inter-trial heterogeneity for the endpoints of PFS (I2=0%, Pheterogeneity=0.52). No publication bias was found by Egger’s test (P=0.991).

BRAF mutation and ORR in mCRC patients with WT KRAS

Information concerning ORR of WT KRAS/mutant BRAF patients was available in 5 studies13,14,22,26,28. The ORR of WT KRAS/WT BRAF mCRC patients was 48.14%, whereas the ORR of mCRC patients with WT KRAS/mutant BRAF was 20.88%. The pooled OR for ORR of WT KRAS/mutant BRAF over WT KRAS/WT BRAF was 0.27 (95% CI=0.10-0.70), with heterogeneity between studies (I2=49%, Pheterogeneity= 0.10). No publication bias was found by Egger’s test (P=0.726).

Figure 1. Flowchart illustrating the procedure of literature search and study selection. EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor; MoAb: monoclonal antibody; mCRc: metastatic colorectal cancer.

Table 1. Characteristics of the 7 included studies

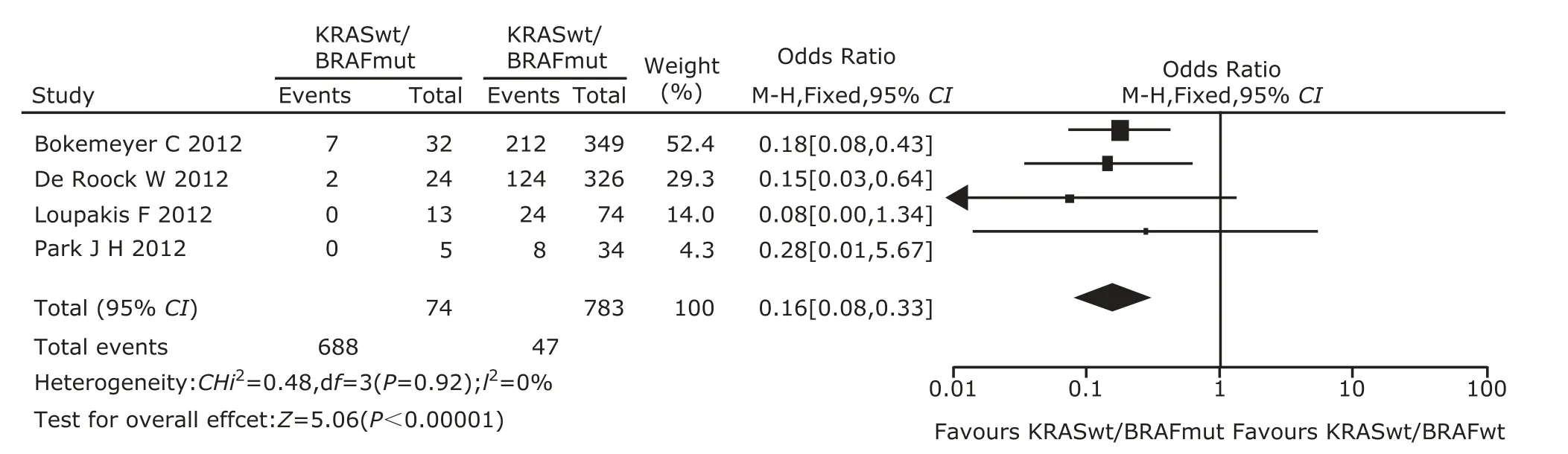

As shown by Galbraith plot, Modest DP’s study showed prominent significance in favor of WT KRAS/mutant BRAF patients and was supposed to be the main cause of heterogeneity. In the meta-regression analysis, treatment protocol (P=0.074), not ethnicity and line of treatment, contributed to heterogeneity. Modest DP et al’s was the only one study using capecitabine while others used fluorouracil. After excluding this study, a second analysis was performed. The pooled OR derived from this analysis was 0.16 (95% CI=0.08-0.33, Fig. 2), with no heterogeneity (Pheterogeneity= 0.92, I2=0%). Modest DP’s trial was a major source of he- terogeneity among the included trials of this meta-analysis.

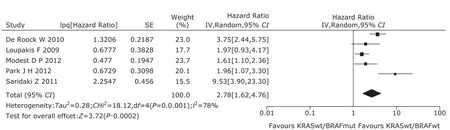

BRAF mutation and PFS in mCRC patients with WT KRAS

5 studies13,22,25,26,28provided adequate information on PFS in patients selected by KRAS mutation. Overall, among mCRC patients with WT KRAS, BRAF mutation predicted a shorter PFS (HR=2.78, 95% CI=1.62-4.76, Fig. 3), with heterogeneity among trials for the analysis. The meta- regression analysis found ethnicity (P=0.631), treatment protocol (P=0.992) and line of treatment (P=0.838) not being the causes of heterogeneity. No publication bias was detected by the Egger’s test (P=0.433).

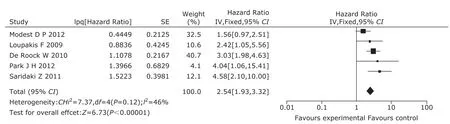

BRAF mutation and OS in mCRC patients with WT KRAS

Data for OS and BRAF mutation in mCRC patients with WT KRAS were reported in 5 studies13,22,25,26,28. BRAF mutation had negative effect on OS in patients with WT KRAS (HR=2.54, 95% CI=1.93-3.32, Fig. 4), with no significant inter-study heterogeneity. In the meta-regression analysis, line of treatment (P=0.096) and treatment protocol (P=0.093) were considered the causes of heterogeneity. Modest DP et al’s study was supposed to be the source of heterogeneity. No publication bias was found (P=0.508).

DISCUSSION

Anti-EGFR MoAbs have shown efficacy in about 10%-20% of mCRC patients. Selection of patients for targeted therapy based upon gene detection is supposed an approach to individualized treatment. The mutations of members of downstream signaling pathways have been proved to result in resistance to anti-EGFR MoAbs. The main downstream signaling pathways of EGFR, RAS/RAF/ MARK pathway, regulates vital biological activities such as cell differentiation, cell survival, cell proliferation and cell migration. Mutant KRAS was the first established molecular marker which precludes responsiveness to EGFR-targeted treatment with cetuximab and panitumumab, however, it only accounted for approximately 30%-40% of nonresponsive patients. So carrying WT KRAS does not guarantee mCRC patients’ clinical benefit from anti-EGFR MoAbs. Alterations in other downstream effectors of EGFR, such as BRAF, have been found to lead to resistance to anti-EGFR MoAbs.

Figure 2. Meta-analysis of odds ratio with 95% confidential interval for objective response rate of mutant BRAF relative to wild-type BRAF in wild-type KRAS patients after excluding Modest DP’s study.

Figure 3. The forest plot of hazard ratio with 95% confidential interval for progression-free survival of mutant BRAF to wild-type BRAF in wild-type KRAS patients.

Figure 4. The forest plot of hazard ratio with 95% confidential interval for overall survival of mutant BRAF to wild-type BRAF in wild-type KRAS patients.

The most common BRAF mutation was the V600E mutation located in the activation domain of BRAF, a transversion of thymidine to adenine resulted in the substitution of valine for glutamate at codon 600.11The BRAF V600E mutation might have additional important functions in tumors, since activating mutation of BRAF only exists in mCRC patients with WT KRAS, but not in those with KRAS mutation. Preclinical data have demonstrated that WT BRAF cells transfected with transcripts containing BRAF V600E mutation showed resistance to anti-EGFR MoAbs.12It is necessary to uncover the proper interactions between the possible predictive marker and mCRC patients’ responses to anti-EGFR MoAbs. A number of studies have indicated that BRAF mutation was associated with poor clinical outcome, but the results were contradictory and could not reach a conclusion. In this meta-analysis, we focused on the relation between BRAF mutation and the therapeutic effects of anti-EGFR MoAbs in mCRC patients.

Five retrospective studies and 2 prospective ones were included in this meta-analysis. In all the studies, a total of 1352 patients were recruited to assess the association of BRAF V600E and anti-EGFR therapeutic effects in mCRC patients. Mao et al29has described the BRAF V600E mutations and ORR in unselected mCRC patients treated with anti-EGFR MoAbs in a meta-analysis. Therefore, we described the relation between BRAF mutations and PFS in unselected mCRC treated with anti-EGFR MoAbs directly. BRAF mutation had a negative effect on PFS of mCRC patients treated with anti-EGFR MoAbs (HR=3.66, 95% CI=2.58-5.20). Particularly in patients with WT KRAS, we found that mCRC patients with BRAF mutation had worse response rate and survival than WT BRAF when they both received anti-EGFR MoAbs (OR=0.27, 95% CI=0.10-0.70; PFS, HR=2.78, 95% CI=1.62-4.76; OS, HR=2.54, 95% CI=1.93-3.32).

Several limitations of this meta-analysis need to be considered when interpreting the findings. Heterogeneity was a potential problem that may affect the interpretation of meta-analysis. In the analysis of BRAF mutation and ORR in mCRC patients with WT KRAS, the heterogeneity disappeared after excluding Modest DP et al’s study, which showed prominent significance in favor of WT KRAS/BRAF mutation patients. The result might be explained by the different chemotherapy protocols. In the 5 studies, only Modest DP’s study used capecitabine combined with cetuximab. A second analysis showed the pooled OR was 0.16 (95% CI=0.08-0.33), with no heterogeneity (Pheterogeneity=0.92, I2=0%). Significant heterogeneity existed in the analysis of BRAF mutation and PFS in mCRC patients with WT KRAS. The meta-regression analysis did not find out the sources of this heterogeneity. Patients in the same trials often received various treatment protocols and the treatment protocols that patients received in different studies were always distinct, which might be where heterogeneity emerged.

In the next place, the amount of studies included in this meta-analysis was quite small. Due to the low prevalence of BRAF mutation, there is a lack of large prospective clinical trials to validate the precise conclusion. Furthermore, it is apparent that mCRC is a heterogeneous disease involving numerous activation mutations in oncogene and inactivation mutations in tumor suppressor gene. Due to the low degree of accuracy and reproducibility of prognosis with single mutation, it is insufficient to only explore the predictive role of KRAS and BRAF point mutations in the mCRC patients treated with anti-EGFR MoAbs. The identification of mutations in other members of EGFR pathway and synergetic effect of multiple genetic mutations in the oncogenic signaling cascades might increase the prediction ability of the biomarkers. Thirdly, our result was based on unadjusted estimates, while a more precise analysis should be conducted if more detailed individual data were allowed for an adjusted estimate by other prognostic factors such as sex, age, tumor location, previous chemotherapy lines and other biomarkers. At last, there is now growing evidence that the presence of a BRAF V600E mutation identifies patients with poorer prognosis, regardless of the treatment regimen. The predictive value of BRAF V600E mutation for lack of response to anti-EGFR MoAbs need to be explored in large prospective randomized studies.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis provided evidence that BRAF V600E mutation may be related to lack of response and worse survival in WT KRAS mCRC patients treated with anti-EGFR MoAbs. BRAF mutation may be used as an additional biomarker for the selection of mCRC patients who might benefit from anti-EGFR MoAbs therapy. However, the amount of studies included in this meta-analysis was limited. These findings need to be further explored and verified in larger prospective randomized studies.

1. Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin 2013; 63:11-30.

2. Meyerhardt JA, Mayer RJ. Systemic therapy for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:476-87.

3. Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin 2008; 58:71-96.

4. Twelves C, Wong A, Nowacki MP, et al. Capecitabine as adjuvant treatment for stage III colon cancer. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:2696-704.

5. Kuebler JP, Wieand HS, O’Connell MJ, et al. Oxaliplatin combined with weekly bolus fluorouracil and leucovorin as surgical adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II and III colon cancer: results from NSABP C-07. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25:2198-204.

6. Van Cutsem E, K?hne CH, Hitre E, et al. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:1408-17.

7. Zhang L, Ma L, Zhou Q. Overall and KRAS-specific results of combined cetuximab treatment and chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis 2011; 26:1025-33.

8. Lenz HJ, Van Cutsem E, Khambata-Ford S, et al. Multicenter phase II and translational study of cetuximab in metastatic colorectal carcinoma refractory to irinotecan, oxaliplatin, and fluoropyrimidines. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24:4914-21.

9. Saltz LB, Meropol NJ, Loehrer PJ Sr, et al. Phase II trial of cetuximab in patients with refractory colorectal cancer that expresses the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22:1201-8.

10. Walther A, Johnstone E, Swanton C, et al. Genetic prognostic and predictive markers in colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2009; 9:489-99.

11. Ikenoue T, Hikiba Y, Kanai F, et al. Functional analysis of mutations within the kinase activation segment of B-Raf in human colorectal tumors. Cancer Res 2003; 63:8132-7.

12. Di Nicolantonio F, Martini M, Molinari F, et al. Wild-type BRAF is required for response to panitumumab or cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26:5705-12.

13. Loupakis F, Ruzzo A, Cremolini C, et al. KRAS codon 61, 146 and BRAF mutations predict resistance to cetuximab plus irinotecan in KRAS codon 12 and 13 wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2009; 101: 715-21.

14. Bokemeyer C, Van Cutsem E, Rougier P, et al. Addition of cetuximab to chemotherapy as first-line treatment for KRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: pooled analysis of the CRYSTAL and OPUS randomised clinical trials. Eur J Cancer 2012; 48:1466-75.

15. Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, et al. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials 2007 Jun 7 [cited 2014 Apr 1]; 8:16. Available from: http://www.trialsjournal.com/content/8/ 1/16.

16. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002; 21:1539-58.

17. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003; 327:557-60.

18. Galbraith RF. A note on graphical presentation of estimated odds ratios from several clinical trials. Stat Med 1988; 7:889-94.

19. Egger M, Davey SG, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta- analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997; 315:629-34.

20. Laurent-Puig P, Cayre A, Manceau G, et al. Analysis of PTEN, BRAF, and EGFR status in determining benefit from cetuximab therapy in wild-type KRAS metastatic colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27:5924-30.

21. Sartore-Bianchi A, Di Nicolantonio F, Nichelatti M, et al. Multi-determinants analysis of molecular alterations for predicting clinical benefit to EGFR-targeted monoclonal antibodies in colorectal cancer. PLoS One 2009 Oct 2 [cited 2014 Apr 1]; 4:e7287. Available from: http://www. plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal. pone.0007287.

22. De Roock W, Claes B, Bernasconi D, et al. Effects of KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, and PIK3CA mutations on the efficacy of cetuximab plus chemotherapy in chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: a retrospective consortium analysis. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11:753-62.

23. Fornaro L, Baldi GG, Masi G, et al. Cetuximab plus irinotecan after irinotecan failure in elderly metastatic colorectal cancer patients: clinical outcome according to KRAS and BRAF mutational status. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2011; 78:243-51.

24. Souglakos J, Philips J, Wang R, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of common mutations for treatment response and survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2009; 101:465-72.

25. Saridaki Z, Tzardi M, Papadaki C, et al. Impact of KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA mutations, PTEN, AREG, EREG expression and skin rash in ≥ 2 line cetuximab-based therapy of colorectal cancer patients. PLoS One 2011 Jan 22 [cited 2014 Apr 1]; 6:e15980. Available from: http://www.plosone. org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.001 5980.

26. Park JH, Han SW, Oh DY, et al. Analysis of KRAS, BRAF, PTEN, IGF1R, EGFR intron 1 CA status in both primary tumors and paired metastases in determining benefit from cetuximab therapy in colon cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2011; 68:1045-55.

27. Ulivi P, Capelli L, Valgiusti M, et al. Predictive role of multiple gene alterations in response to cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer: a single center study. J Transl Med 2012 May 8 [cited 2014 Apr 1]; 10:87. Available from: http://www.translational-medicine.com/ content/10/1/87.

28. Modest DP, Jung A, Moosmann N, et al. The influence of KRAS and BRAF mutations on the efficacy of cetuximab-based first-line therapy of metastatic colorectal cancer: an analysis of the AIO KRK-0104-trial. Int J Cancer 2012; 131:980-6.

29. Mao C, Liao RY, Qiu LX, et al. BRAF V600E mutation and resistance to anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Mol Biol Rep 2011; 38:2219-23.

Chinese Medical Sciences Journal2014年4期

Chinese Medical Sciences Journal2014年4期

- Chinese Medical Sciences Journal的其它文章

- Inhibition of Xanthine Oxidase Activity by Gnaphalium Affine Extract

- Evaluation of Risk Factors for Arytenoid Dislocation after Endotracheal Intubation: a Retrospective Case-control Study

- Non-enhanced Low-tube-voltage High-pitch Dual-source Computed Tomography with Sinogram Affirmed Iterative Reconstruction Algorithm of the Abdomen and Pelvis

- Primary Combined Intra-articular and Extra-articular Synovial Osteochondromatosis of Shoulder: a Case Report

- Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Small Intestine: a Case Report△

- Multiple Myeloma Mimicking Spondyloarthritis: a Case Report