Non-enhanced Low-tube-voltage High-pitch Dual-source Computed Tomography with Sinogram Affirmed Iterative Reconstruction Algorithm of the Abdomen and Pelvis

Hao Sun, Hua-dan Xue, Zheng-yu Jin, Xuan Wang, Yu Chen, Yong-lan He, Da-ming Zhang, and Liang Zhu

Department of Radiology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China

RECENT advances in computed tomography (CT) have brought larger volume coverage, better image resolution, shorter scanning time, and more accurate imaging interpretation. In the United States, the number of CT scans performed has increased from 13 million in 1990 to 62 million in 2006.1As the number of CT examinations continuously grows, the concerns about the associated radiation exposure and its potential link to the pathogenesis of cancer have been raised.2Dose reduction techniques therefore came into the focus of clinical research.3-7Several approaches have been developed to decrease the radiation dose of CT scans as well as achieving diagnostic image quality. Tube potential (peak voltage) determines incident x-ray beam energy and variation in tube potential causes a substantial change in CT radiation dose. In addition, the tube voltage affects both image noise and tissue contrast, decreased tube voltage is accompanied with a notable increase in image noise.3For helical CT scanners, higher pitch (defined as table feed per rotation) decreases the radiation dose because of a shorter exposure time. For a given collimation, a raise in table speed increases the pitch and reduces the radiation dose by 1 divided by the pitch.8Iterative reconstruction has recently been introduced into routine CT imaging. It has been demonstrated that iterative reconstruction algorithms can improve image quality and reduce radiation dose compared with the traditional filtered back-projection (FBP) approach in abdomen scan.9-13Sinogram affirmed iterative reconstruction (SAFIRE) is a recently developed raw-data- based iterative reconstruction algorithm. The SAFIRE algorithm makes multiple comparisons between the recon- structed and the measured data in the raw data domain, and iteratively corrects the images.14

Until now, most standard abdominopelvic CT scans still require a significant breath-hold time, which may not be possible for some emergent patients. For those patients, a more rapid CT examination may be necessary to obtain images that are not degraded by motion artifact. The second-generation dual-source CT (DSCT) system with two 128-slice detectors enables scanning at a high pitch. In high-pitch scanning, data are acquired in a spiral mode with a high pitch equaling a table feed of up to 46 cm/s. To the best of our knowledge, there have been only two studies investigating the effect of high-pitch CT on image quality and radiation dose of routine abdominal and pelvic CT.15,16

The purpose of the present prospective study was to investigate the image quality, radiation dose and diagnostic performance of low-tube-voltage high-pitch DSCT with SAFIRE algorithm for routine abdominal and pelvic scans, compared with the standard CT protocol.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study patients

This prospective study was conducted in patients visiting the Department of Emergency of our hospital with clinical symptoms of abdominopelvic pain from November to December 2012. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board, and written informed consent for additional abdominal and pelvic DSCT scan was obtained from each patient or patient’s family. Patients’ height and weight data were collected for the calculation of body mass index (BMI, kg/m2). For each patient, the sum of the anteroposterior and mediolateral thickness (hereinafter referred to as body thickness) was calculated at the level of the renal arteries.17Patients younger than 18 years old, pregnant, or lactating were excluded.

CT imaging protocol

All CT images were acqui red using a DSCT scanner (128-slice Somatom Definition Flash with Stellar detector; Siemens Healthcare, Forchheim, Germany). Patients underwent imaging in a cranio-caudal direction during a full inspiratory breath-hold. First, a standard non-enhanced CT scan (protocol 1) was performed with the following parameters: tube potential 120 kVp, reference tube current 210 mAs, pitch 0.9, collimation 128×0.6 mm, rotation time 0.5 s. Then, a high-pitch non-enhanced CT scanning (protocol 2) was performed with the following parameters: a semi-automated attenuation-based tube voltage selection algorithm with tube current adaption (CAREkV, Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) (tube potential 100 kVp, reference tube potential 120 kVp, indicated by the “unenhanced” icon on the user interface), reference tube current 210 mAs, pitch 3.0, collimation 128×0.6 mm, rotation time 0.28 s. The field of view (FOV) of protocol 2 was 330 mm due to the smaller detector. The scan ranges of the 2 protocols were both from the dome of the diaphragm to the pelvic floor. Automatic exposure control (Care DOSE 4D, Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) was applied for both protocols.

Image processing and analysis

The CT data were reconstructed into axial images with a slice thickness of 2 mm and an increment of 2 mm. For protocol 1, a medium smooth convolution kernel B30f was selected for FBP. For protocol 2, the kernel I30f was used for SAFIRE with the conservative strength level of “3”. The images were reviewed on the picture archiving and communication systems using a commercially available workstation (Synapse, Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).

For each patient, one radiologist with 7-year experience in interpreting abdominal CT recorded CT numbers and noise of the liver, pancreas, spleen, kidneys, abdominal aorta and psoas muscle by placing a circular region of interest (ROI) of 0.2-1.0 cm2in size at each anatomical site for protocol 1 and protocol 2 images. Attenuation was assessed from three ROIs of the liver, pancreas and spleen, two ROIs of each kidney, one ROI of the abdominal aorta and psoas muscle. CT values were averaged for each region and corresponding standard deviations were determined. Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) was calculated by dividing the mean attenuation number by the corresponding standard deviation. The overall image noise was defined by the standard deviation of the pixel values from a circular ROI with mean size of 1.0 cm2drawn in the subcutaneous fat of the anterior abdominal wall.18

Two radiologists with 10- and 25-year experience in interpreting CT images, who were blind to the acquisition of the images, evaluated the image quality of two sets of unenhanced images independently, with discordant evaluation resolved by consensus. The image quality was rated according to a five-point scale as reported previously.15High-pitch CT images with scores ≥ 3 were regarded as diagnostic, ≥ 4 as having the potential to replace standard CT images. Patients’ width of excluded abdominal organs on high-pitch CT images was measured by one radiologist as none, mild (<1 cm of the organs excluded), moderate (1-2 cm of the organs excluded), or severe (>2 cm of the organs excluded). Image readers were required to record the artifacts, such as windmill, beam hardening artifacts and motion artifacts.

Two radiologists with 7- and 10-year experience in abdominal CT interpretation respectively, who were blind to the acquisition of the images, recorded the abdominopelvic lesions detected on two unenhanced image sets in consensus.

Scan time and radiation dose

For two CT protocols, the scan ti me and dose-length product (DLP, mGy cm) were recorded from the CT scanner report. DLP is a measure of total radiation exposure for the whole series of images. The effective radiation dose in millisieverts (mSv) was estimated using the DLP and conversion coefficient κ [κ= 0.015 mSv/(mGy cm)].19

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Normality of the data was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Paired-samples t-test was used to compare CT number, noise and SNR of all organs, image quality and effective radiation dose in two CT protocols. The correlations of overall image noise and effective radiation dose with body thickness in two protocols were analyzed with a linear regression analysis. Kappa statistics were calculated to assess agreement between the image quality evaluations of protocols 1 and 2 by two radiologists. P values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

General information

64 patients were enrolled in this study, including 39 male and 25 female, with a mean age of 54±15 years (19-80 years). The mean height, weight, BMI and body thickness were 166.4±7.9 cm (150.0-183.0 cm), 68.3±13.7 kg (42.0-110.0 kg), 24.5±3.9 kg/m2(16.6-35.2 kg/m2), 55.2± 6.6 cm (39.7-73.4 cm), respectively.

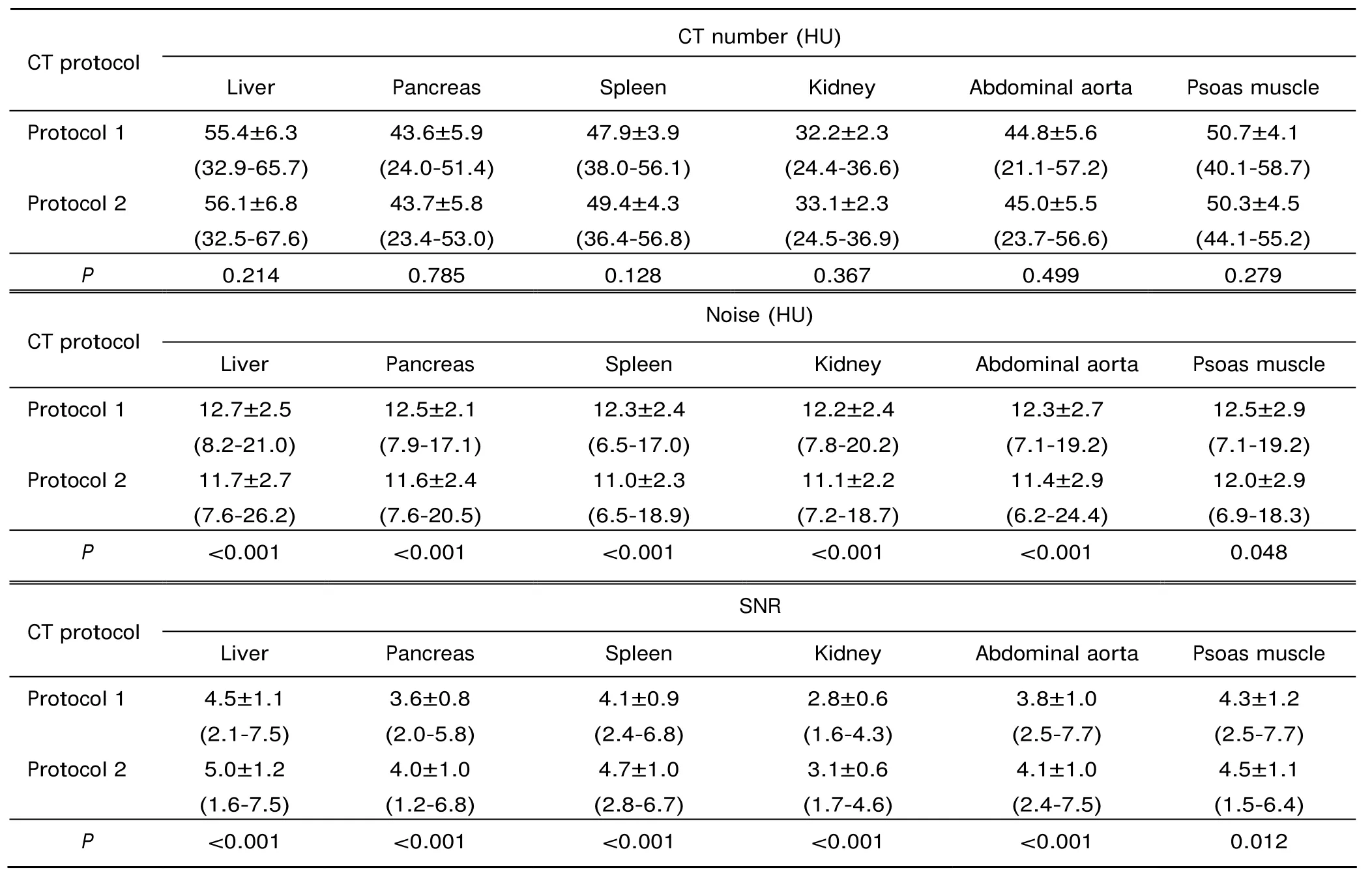

Mean CT number, noise and SNR

There were no statistically significant differences in CT numbers of the liver, pancreas, spleen, kidneys, abdominal aorta and psoas muscle between two CT protocol images (all P>0.05). Noise of all organs was found lower in CT protocol 2 images than in CT protocol 1 images (all P<0.05). SNR on images of protocol 2 was higher than that of protocol 1 (all P<0.05) (Table 1). The overall image noise of protocol 2 (9.8±3.1 HU, 5.4-18.9 HU) was lower than that of protocol 1 (11.1±3.0 HU, 4.6-23.7 HU) (P<0.001). A high correlation was found between the overall image noise and the body thickness for protocol 2 CT scans (r=0.542).

Table 1. Mean CT number, noise and SNR of ROI measured in two series of unenhanced images [±s (range)]

Table 1. Mean CT number, noise and SNR of ROI measured in two series of unenhanced images [±s (range)]

Protocol 1: standard CT scans [120 kVp/pitch of 0.9/filtered back-projection (FBR)]; Protocol 2: high-pitch CT scans [100 kVp/pitch of 3.0/sonogram affirmed iterative reconstruction (SAFIRE)]; SNR: signal-to-noise ratio; ROI: region of interest.

CT number (HU) CT protocol Liver Pancreas Spleen Kidney Abdominal aorta Psoas muscle Protocol 1 55.4±6.3 (32.9-65.7) 43.6±5.9 (24.0-51.4) 47.9±3.9 (38.0-56.1) Protocol 2 32.2±2.3 (24.4-36.6) 44.8±5.6 (21.1-57.2) 50.7±4.1 (40.1-58.7) 50.3±4.5 (44.1-55.2) P 0.214 0.785 0.128 0.367 0.499 0.279 56.1±6.8 (32.5-67.6) 43.7±5.8 (23.4-53.0) 49.4±4.3 (36.4-56.8) CT protocol 33.1±2.3 (24.5-36.9) 45.0±5.5 (23.7-56.6) Noise (HU) Liver Pancreas Spleen Kidney Abdominal aorta Psoas muscle Protocol 1 12.7±2.5 (8.2-21.0) 12.5±2.1 (7.9-17.1) 12.3±2.4 (6.5-17.0) Protocol 2 11.7±2.7 (7.6-26.2) 12.2±2.4 (7.8-20.2) 12.3±2.7 (7.1-19.2) 12.5±2.9 (7.1-19.2) 12.0±2.9 (6.9-18.3) P <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.048 11.6±2.4 (7.6-20.5) 11.0±2.3 (6.5-18.9) CT protocol 11.1±2.2 (7.2-18.7) 11.4±2.9 (6.2-24.4) SNR Liver Pancreas Spleen Kidney Abdominal aorta Psoas muscle Protocol 1 4.5±1.1 (2.1-7.5) 3.6±0.8 (2.0-5.8) 4.1±0.9 (2.4-6.8) Protocol 2 5.0±1.2 (1.6-7.5) 2.8±0.6 (1.6-4.3) 3.8±1.0 (2.5-7.7) 4.3±1.2 (2.5-7.7) 4.5±1.1 (1.5-6.4) P <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.012 4.0±1.0 (1.2-6.8) 4.7±1.0 (2.8-6.7) 3.1±0.6 (1.7-4.6) 4.1±1.0 (2.4-7.5)

Image quality

In 60 patients (60/64, 93.75%), all the abdominopelvic organs were included in the FOV of smaller detector. Mild exclusion of liver, spleen and/or gut in 4 patients (4/64, 6.25%) was observed. Neither moderate nor severe exclusion was found from the FOV of smaller detector. In these four patients, exclusion of abdominal organs can be avoided by careful positioning for two patients with body thickness less than 65 cm (60.6 cm and 62.3 cm, respectively).

Inter-observer agreement between the individual evaluation results of two radiologists in image quality was excellent (κ=0.802). Consensus image quality scores were 4.6±0.5 and 4.1±0.7 for protocol 1 and protocol 2, respectively (P<0.001). There were 13 (20.3%), 29 (45.3%) and 22 (34.4%) images of protocol 2 rated as score 3, 4 and 5 respectively, i.e. all the images obtained in protocol 2 were of diagnostic quality. 51 (79.7%) high-pitch CT images were scored as having the potential to replace standard CT images. More windmill and beam hardening artifacts were observed on protocol 2 images than on protocol 1 images (windmill artifacts, 64 vs. 4; beam hardening artifacts, 9 vs. 3). Motion artifacts were only found on protocol 1 images (3/64). All the artifacts were classified as not affecting diagnostic value.

Detection of abdominopelvic lesions

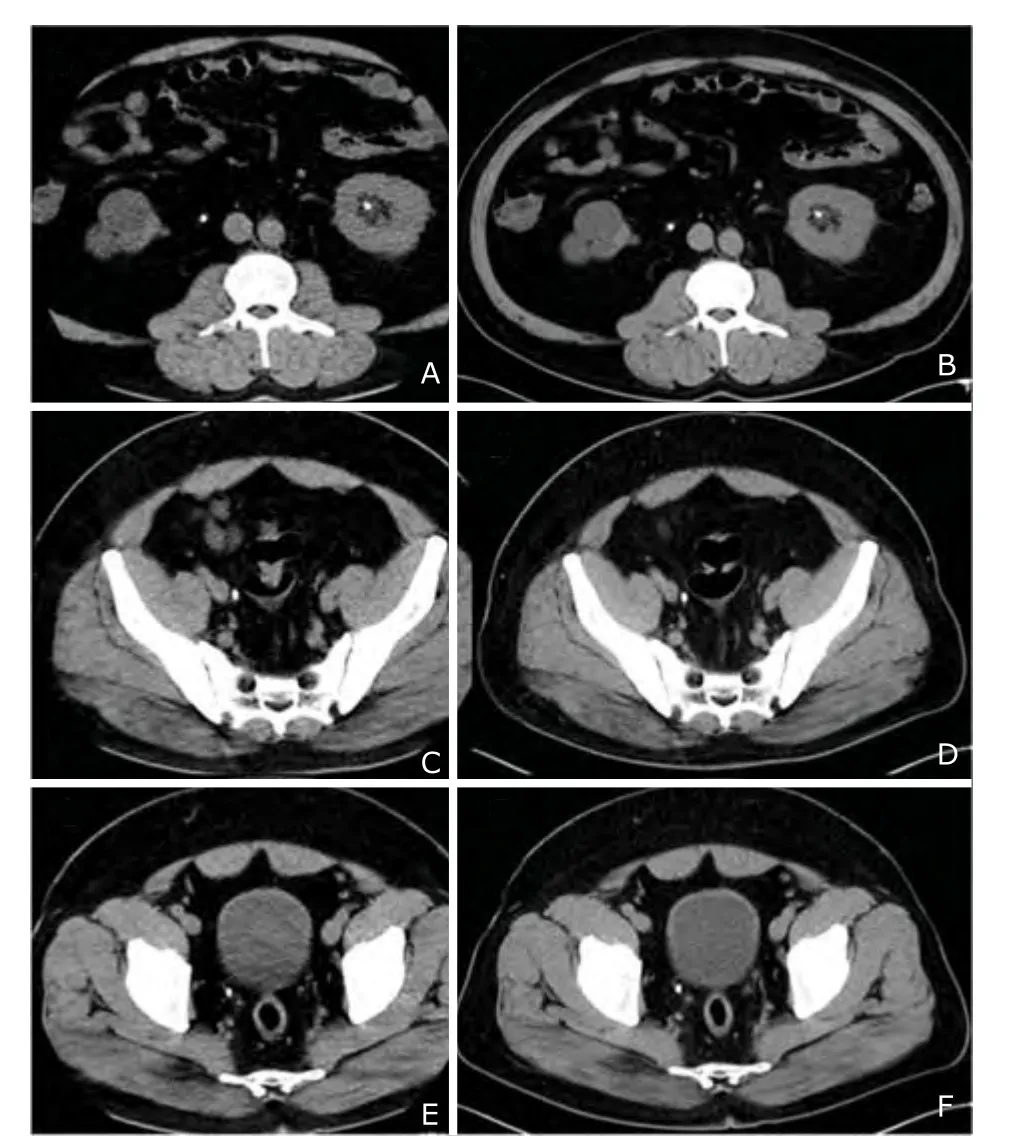

There were 234 lesions detected in protocol 1 CT images, including hepatic hamartoma (1), hepatic cysts (48), liver calcifications (10), suspected hepatic hemangiomas (3), gallstones (12), splenic calcifications (9), adrenal mass (1), renal cysts (48), renal angiomyolipoma (2), renal masses (4), renal pelvic mass (1), kidney stones (42), ureteral masses (2), ureteral stones (9), ureterocele (1), bladder masses (3), enlarged prostate (9), prostate calcifications (17), transverse colonic intussusceptions (1), duodenal diverticulum (1), adnexal masses (4), calcification of seminal vesicle (1), pelvic ascites (2), retroperitoneal lymph nodes enlargement (1) and pulmonary masses (2). No lesions were located in excluded organs visualized on protocol 2 CT images. Of the 234 lesions, 229 (97.9%) were also detected in protocol 2 CT images. The 5 missed lesions included three renal stones < 3 mm in diameter, one liver cyst < 5 mm and one prostate calcification < 3 mm, which were all considered to be not related to the patients’ clinical symptoms. The lesions of 6 patients with BMI >30.0 kg/m2were all detected in protocol 2 CT images (Fig. 1).

Scan time and radiation dose

The mean scan time of protocol 2 was 1.4±0.1 seconds (1.2-1.6 seconds) for the whole abdomen and pelvis, significantly shorter than that of protocol 1 (7.6±0.6 seconds, 6.6-9.0 seconds, P<0.001). The estimated effective radiation dose of protocol 2 was 4.4±0.4 mSv (3.3-5.6 mSv), significantly lower than that of protocol 1 (7.3±2.4 mSv, 3.9-18.1 mSv, P<0.001), with a mean dose reduction of 41.4% (17.7%-72.9%). Effective radiation dose was shown correlated with body thickness for protocol 2 CT scans (r=0.754).

DISCUSSION

Figure 1. In a patient with body mass index of 35.1 kg/m2, multiple urinary stones were all demonstrated on the images of protocol 2 (A, C, E) using 100 kVp, pitch of 3.0 and SAFIRE algorithm as well as on the images of protocol 1 (B, D, F) using 120 kVp, pitch of 0.9 and FBP algorithm.

CT exposes the patient to ionizing radiation and increases the risk of cancer such as lung cancer and breast cancer.3,20,21Therefore, it is important for radiologists to be aware of options that can potentially decrease the radiation dose without compromising diagnostic image quality. If other parameters are kept constant, lowering the tube potential can reduce the radiation dose effectively in CT urography,17,22pediatric CT23,24and cerebral perfusion CT for stroke patients.25Attenuation-based automatic tube voltage selection algorithm was developed and demonstrated to be applicable in clinical routine contrast-enhanced thoracoabdominal CT26and abdominal CT27,28to achieve a significant dose reduction while preserving image quality. Most recently, SAFIRE algorithm was introduced into contrast-enhanced abdominal CT28and low-dose lung CT.29To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the image quality and radiation dose of low-tube-voltage high-pitch DSCT with SAFIRE for non-enhanced abdominal and pelvic scans. Concurrently, we have also compared the diagnostic performance for abdominopelvic lesions between this new CT scan protocol and standard CT scan protocol.

Our study indicates that the use of low-tube-voltage high-pitch DSCT with SAFIRE (protocol 2) is associated with similar CT number, lower noise, higher SNR and good diagnostic image quality compared with standard CT scan with FPB (protocol 1) for abdominal and pelvic organs. Conventional automated attenuation-based tube current modulation approaches modulate only the X-ray tube current (mAs), while the X-ray tube voltage (the kV setting) is left unchanged. However, there exists a large potential for dose reduction in optimizing the X-ray tube kV setting.30-32In our study, we chose tube voltage of 100 kVp to decrease the radiation dose. However, this may result in a higher image noise and a subsequent loss in image quality. A semi-automated attenuation-based tube voltage selection algorithm with tube current adaption (CAREkV, Siemens Medical Solutions) can compensate for higher image noise by increasing the tube current based on the individual patient’s anatomy. In addition, we used SAFIRE algorithm to improve image quality. SAFIRE is one of the most recently introduced iterative reconstruction processes. As compared to previous image domain-based techniques, SAFIRE uses a noise modeling technique supported by the raw data (sinogram data) with the aim of reducing noise and maintaining image sharpness.28,29It should be noted that lowering the tube voltage is usually recommended for enhanced CT and CT angiography because of the increased X-ray absorption of iodine at lower tube voltage.9-11Hu et al33found that 100 kV imaging protocols of non-enhanced chest CT are possible for most patients, but the patients in their study had relatively small body size and low BMI than those in our study. In our study, the mean BMI of the patients was close to the upper limit of normal value (25 kg/m2), and we found that 100 kV imaging protocol was proper for non-enhanced abdomen and pelvis CT.

Increasing the pitch is another option to reduce the radiation exposure. The second-generation DSCT system with two 128-slice detectors enables to scan with a pitch of up to 3.2 for the abdomen and pelvis, correlating to a table feed of up to 46 cm/s. A very important advantage of the high-pitch CT is the reduction of scan time. In our study, high-pitch DSCT demonstrated a more than four fifths reduction in scan time compared with standard CT, which is concordant with the result of Hardie et al15. Shorter scan time contributes to less motion artifacts in high-pitch scanning than in standard-pitch CT, owing to the minimization of motion artifacts by fast volume coverage. Baumueller et al29demonstrated that diagnostic image quality of the lung parenchyma could be maintained in high-pitch chest CT even with respiration. Our study showed that motion artifacts were not found on high-pitch CT images. This indicates that the high-pitch mode may be applicable in non-cooperative and respiration-suspension impossible patients.

Our study revealed that radiation dose of low-tube- voltage high-pitch DSCT with SAFIRE was lower than that of standard CT, with a dose reduction of approximately 40%. In this low-dose scanning mode, the image quality was still good and diagnostic, and most lesions in the abdomen and pelvis were detected. Reasons for lesion miss were beam hardening artifacts from metallic material, and the missed lesions were all considered to be not related to the patients’ clinical symptoms. The lesions of 6 patients with large BMI (> 30.0 kg/m2) were all diagnosed in the low-tube-voltage high-pitch DSCT with SAFIRE, proving the applicability of this CT protocol in obese patients.

Our study has the following limitations: firstly, we did not evaluate the performance of contrast-enhanced low-tube-voltage high-pitch DSCT with SAFIRE, which is one direction of future study. Secondly, windmill artifacts were observed in the pelvis on all the high-pitch CT images. Although scanning at a higher pitch is generally more dose efficient, it also tends to cause helical artifacts, degradation of the section-sensitivity profile (section broadening), and decrease in spatial resolution. In our study, the image quality of high-pitch scanning may be compensated by SAFIRE algorithm and all the artifacts were considered to be not affecting diagnostic value. Finally, partially excluded liver, spleen and/or gut that is not covered by the detector with a smaller FOV may influence detection of lesions in obese patients. This may be improved by careful positioning.

In conclusion, low-tube-voltage high-pitch DSCT with SAFIRE achieves less noise and preserves similar image quality compared with the conventional CT protocol in non-enhanced abdominal and pelvic scans. Radiation dose of this CT scanning mode was decreased to 60% that of conventional CT. High-pitch DSCT can reduce scan time, which is especially useful in emergent patients. This DSCT protocol has good diagnostic performance in abdomen and pelvic disease and is clinically applicable.

1. McCollough CH, Primak AN, Braun N, et al. Strategies for reducing radiation dose in CT. Radiol Clin N Am 2009; 47:27-40.

2. Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomography – an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:2277-84.

3. Kalra MK, Maher MM, Toth TL, et al. Strategies for CT radiation dose optimization. Radiology 2004; 230:619-28.

4. Hausleiter J, Meyer T, Hadamitzky M, et al. Radiation dose estimates from cardiac multislice computed tomography in daily practice: impact of different scanning protocols on effective dose estimates. Circulation 2006; 113:1305-10.

5. Kalender WA, Buchenau S, Deak P, et al. Technical approaches to the optimisation of CT. Phys Med 2008; 24:71-9.

6. Hausleiter J, Meyer T, Hermann F, et al. Estimated radiation dose associated with cardiac CT angiography. JAMA 2009; 301:500-7.

7. Coakley FV, Gould R, Yeh BM, et al. CT radiation dose: what can you do right now in your practice? AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011; 196:619-25.

8. Mahesh M, Scatarige JC, Cooper J, et al. Dose and pitch relationship for a particular multislice CT scanner. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001; 177:1273-5.

9. Sagara Y, Hara AK, Pavlicek W, et al. Abdominal CT: comparison of low-dose CT with adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction and routine-dose CT with filtered back projection in 53 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2010; 195:713-9.

10. Prakash P, Kalra MK, Kambadakone AK, et al. Reducing abdominal CT radiation dose with adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction technique. Invest Radiol 2010; 45:202-10.

11. Marin D, Nelson RC, Schindera ST, et al. Low-tube-voltage, high-tube-current multidetector abdominal CT: improved image quality and decreased radiation dose with adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction algorithm--initial clinical experience. Radiology 2010; 254:145-53.

12. Martinsen AC, S?ther HK, Hol PK, et al. Iterative reconstruction reduces abdominal CT dose. Eur J Radiol 2012; 81:1483-7.

13. Deák Z, Grimm JM, Treitl M, et al. Filtered back projection, adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction, and a model-based iterative reconstruction in abdominal CT: an experimental clinical study. Radiology 2013; 266:197-206.

14. Wang R, Schoepf UJ, Wu R, et al. CT coronary angiography: image quality with sinogram affirmed iterative recon- struction compared with filtered back-projection. Clin Radiol 2013; 68:272-8.

15. Hardie AD, Mayes N, Boulter DJ. Use of high-pitch dual-source computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis to markedly reduce scan time: clinical feasibility study. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2011; 35:353-5.

16. Amacker NA, Mader C, Alkadhi H, et al. Routine chest and abdominal high-pitch CT: an alternative low dose protocol with preserved image quality. Eur J Radiol 2012; 81:e392-7.

17. Shinagare AB, Sahni VA, Sadow CA, et al. Feasibility of low-tube-voltage excretory phase images during CT urography: assessment using a dual-energy CT scanner. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011; 197:1146-51.

18. Zhang LJ, Peng J, Wu SY, et al. Liver virtual non-enhanced CT with dual-source, dual-energy CT: a preliminary study. Eur Radiol 2010; 20:2257-64.

19. Shrimpton PC, Hillier MC, Lewis MA, et al. National survey of doses from CT in the UK: 2003. Br J Radiol 2006; 79:968-80.

20. Brenner DJ. Radiation risks potentially associated with low-dose CT screening of adult smokers for lung cancer. Radiology 2004; 231:440-5.

21. Einstein AJ, Henzlova MJ, Rajagopalan S. Estimating risk of cancer associated with radiation exposure from 64-slice computed tomography coronary angiography. JAMA 2007; 298:317-23.

22. Lee S, Jung SE, Rha SE, et al. Reducing radiation in CT urography for hematuria: effect of using 100 kilovoltage protocol. Eur J Radiol 2012; 81:e830-4.

23. Baum U, Anders K, Steinbichler G, et al. Improvement of image quality of multislice spiral CT scans of the head and neck region using a raw data-based multidimensional adaptive filtering (MAF) technique. Eur Radiol 2004; 14:1873-81.

24. Singh S, Kalra MK, Moore MA, et al. Dose reduction and compliance with pediatric CT protocols adapted to patient size, clinical indication, and number of prior studies. Radiology 2009; 252:200-8.

25. Haberland U, Klotz E, Abolmaali N. Performance assessment of dynamic spiral scan modes with variable pitch for quantitative perfusion computed tomography. Invest Radiol 2010; 45:378-86.

26. Eller A, May MS, Scharf M, et al. Attenuation-based automatic kilovolt selection in abdominal computed tomography: effects on radiation exposure and image quality. Invest Radiol 2012; 47:559-65.

27. Lee KH, Lee JM, Moon SK, et al. Attenuation-based automatic tube voltage selection and tube current modulation for dose reduction at contrast-enhanced liver CT. Radiology 2012; 265:437-47.

28. Shin HJ, Chung YE, Lee YH, et al. Radiation dose reduction via sinogram affirmed iterative reconstruction and automatic tube voltage modulation (CARE kV) in abdominal CT. Korean J Radiol 2013; 14: 886-93.

29. Baumueller S, Winklehner A, Karlo C, et al. Low-dose CT of the lung: potential value of iterative reconstructions. Eur Radiol 2012; 22:2597-606.

30. Herzog C, Mulvihill DM, Nguyen SA, et al. Pediatric cardiovascular CT angiography: radiation dose reduction using automatic anatomic tube current modulation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008; 190:1232-40.

31. Schindera ST, Nelson RC, Yoshizumi T, et al. Effect of automatic tube current modulation on radiation dose and image quality for low tube voltage multidetector row CT angiography: phantom study. Acad Radiol 2009; 16:997-1002.

32. Yu L, Li H, Fletcher JG, et al. Automatic selection of tube potential for radiation dose reduction in CT: a general strategy. Med Phys 2010; 37:234-43.

33. Hu XH, Ding XF, Wu RZ, et al. Radiation dose of non-enhanced chest CT can be reduced 40% by using iterative reconstruction in image space. Clin Radiol 2011; 66:1023-9.

Chinese Medical Sciences Journal2014年4期

Chinese Medical Sciences Journal2014年4期

- Chinese Medical Sciences Journal的其它文章

- Inhibition of Xanthine Oxidase Activity by Gnaphalium Affine Extract

- Evaluation of Risk Factors for Arytenoid Dislocation after Endotracheal Intubation: a Retrospective Case-control Study

- Primary Combined Intra-articular and Extra-articular Synovial Osteochondromatosis of Shoulder: a Case Report

- Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Small Intestine: a Case Report△

- BRAF V600E Mutation as a Predictive Factor of Anti-EGFR Monoclonal Antibodies Therapeutic Effects in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: a Meta-analysis

- Multiple Myeloma Mimicking Spondyloarthritis: a Case Report