Effects of dietary phosphorus level on growth, body composition, liver histology and lipid metabolism of spotted seabass (Lateolabrax maculatus)reared in freshwater

Jilei Zhng, Shuwei Zhng, Kngle Lu, Ling Wng, Ki Song, Xueshn Li,Chunxio Zhng,*, Smd Rhimnejd

a Xiamen Key Laboratory for Feed Quality Testing and Safety Evaluation, Fisheries College, Jimei University, Xiamen, 361021, China

b University of South Bohemia in Ceske Budejovice, Faculty of Fisheries and Protection of Waters, South Bohemian Research Center of Aquaculture and Biodiversity of Hydrocenoses, Zatisi 728/ II, Vodnany, 389 25, Czech Republic

Keywords:Lateolabrax maculatus Phosphorus requirement Lipid metabolism Growth Liver histology Liver fatty acid composition

A B S T R A C T The present study was conducted to determine the effects of dietary phosphorus (P) levels on growth performance, body composition, liver histology and enzymatic activity, and expression of lipid metabolism-related genes in spotted seabass (Lateolabrax maculatus).Seven diets were prepared to contain available P levels of 0.48% (the control group), 0.69%, 0.89%, 1.10%, 1.28%, 1.51% and 1.77% and feed fish (4.26 ± 0.03 g) to satiety twice daily for 10 weeks.Significantly higher weight gain and specific growth rate were recorded at P levels of 0.69%–1.51% compared to the control group.Feed conversion ratio decreased with increasing P levels up to 0.89% and increased thereafter.The lowest liver lipid content, viscerosomatic index and lipid content of whole-body were obtained in the 0.89%-P group among dietary treatments.P and calcium (Ca) contents in whole body were increased, while liver triglyceride and cholesterol contents were decreased with increasing dietary P levels from 0.48% to 1.77%.The highest activity of hepatic lipase was recorded in the 1.10%-P group among dietary treatments.Compared to the control group, 1.10% P enhanced the proportion of HUFA and reduced the proportion of SFA and MUFA.The histological observations showed that P deficiency (0.48%) led to the vacuolization of hepatocytes and increased number of lipid droplets.Meanwhile, overall liver tissue structure was improved when P level increased to 1.28%.Compared to the control group, expression of lipid metabolismrelated genes such as FAS, ACC-2 and SREBP-1 was decreased at 0.89%–1.10% P group while an opposite trend was observed in the expression of PPARa2 and CPT-1 genes.The current study showed that 0.89% dietary P levels could promote growth performance of spotted seabass and reduce lipid accumulation in the liver.A broken-line regression analysis based on weight gain showed that the optimum dietary P level (available P) for juvenile spotted seabass reared in freshwater was 0.72%.

1.Introduction

Phosphorus (P) is one of the most essential minerals in animal nutrition that participates in key metabolic and physiological functions.Furthermore, P plays an important role in the formation and maintenance of bone tissue and acid-base balance, protein synthesis, growth and cell differentiation (Lall, 1991).Although fish can absorb P from the water, feed is the primary source of P for fish, as the concentration of P in water is barely sufficient to meet the P requirement of fish (Sun et al.,2018).

The appropriate amount of phosphorus in commercial feed is of great importance to the environment and economy (Yuan et al., 2011).Inadequate P intake can lead to the loss of appetite, slow growth,decreased feed efficiency, build-up of body fat, abnormal bone mineralization and elevated blood sugar (Sugiura, Hardy, & Roberts, 2004).A snakehead study shows that P deficiency results in poor growth, slightly reduced mineralization and antioxidant capacity, and increased body lipid accumulation (Shen et al., 2017).Inhibition of oxidativephosphorylation has also been reported in fish that lack phosphorus in their diets (Roy & Lall, 2003; Skonberg, Yogev, Hardy, & Dong, 1997).However, extra P is excreted through urine or feces resulting in algal bloom and eutrophication of water (Auer, Kieser, & Canale, 1986; Bureau & Cho, 1999).Therefore, there is a trend to reduce dietary P to the level that satisfies but does not exceed the P requirement in order to achieve the maximum fish growth and protect water quality (Lall,1991).Therefore, the determination of precise P requirement of farmed fish species is crucial to ensure the optimal growth and physiology,prevent lipid accumulation and occurrence of fatty liver.

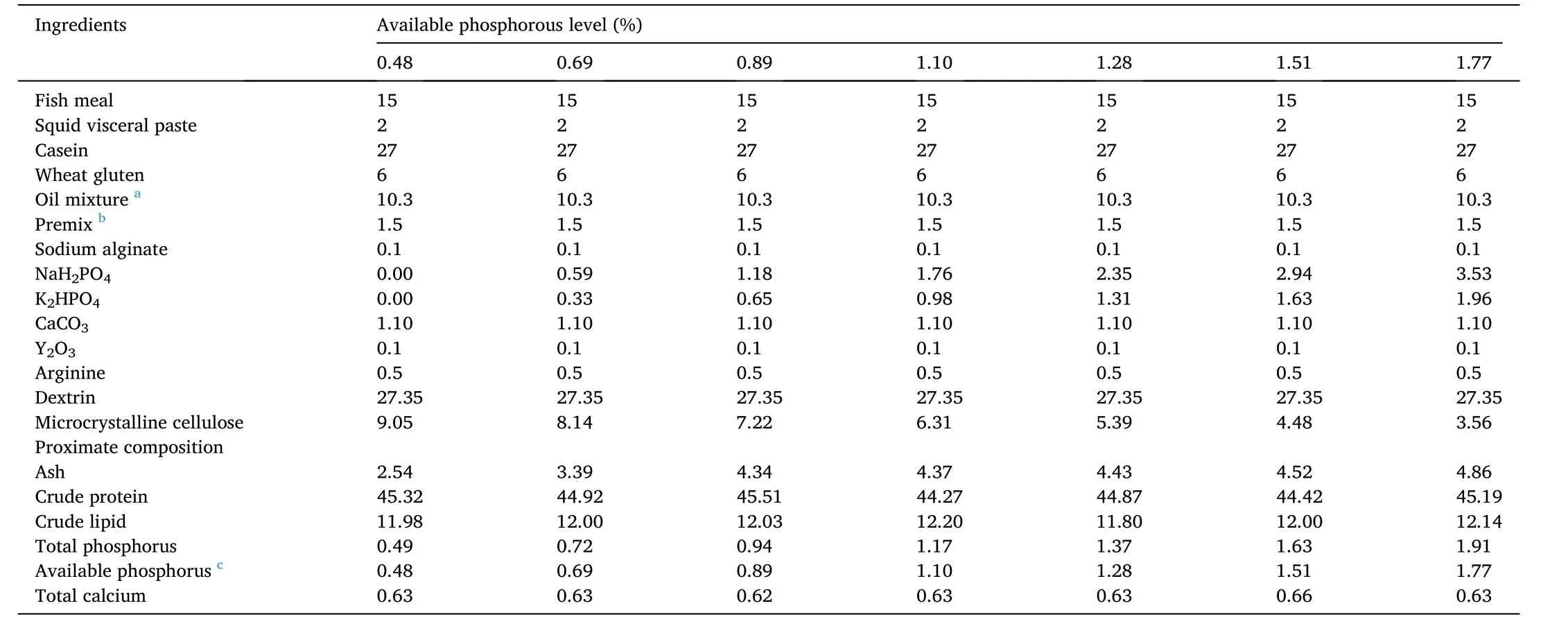

Table 1 Formulation and proximate composition of the experimental diets (% dry matter).

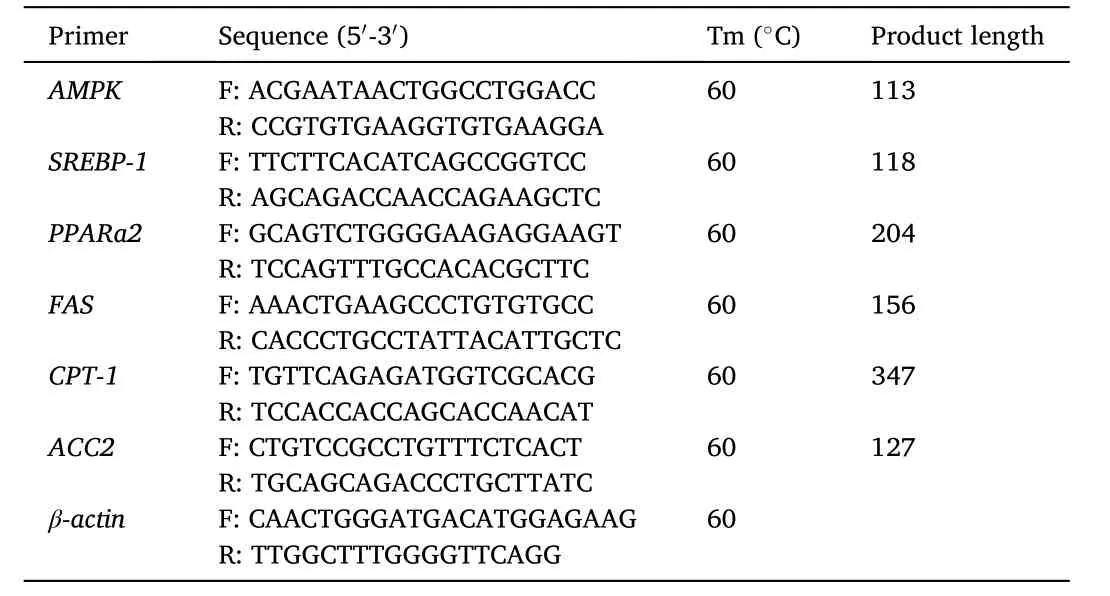

Table 2 Sequence of the primers used for real-time PCR.

Spotted seabass (Lateolabrax maculatus) was a euryhaline fish that has been farmed in eastern and southern China (Lu et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2016a), and its main culture model was freshwater pond and marine cage farming.Salinity is an important environmental factor in aquaculture environment, which can significantly affect the growth and development, metabolism, osmotic pressure regulation, immunefunction and muscle quality of aquaculture animals (Alcala-Carrillo,Castillo-Vargasmachuca, & Ponce-Palafox, 2016; Cotton, Walker, &Recicar, 2003; Imsland et al., 2001; Jarvis & Ballantyne, 2003; Yan, Li,Xiong, & Zhu, 2004).The P requirement of the same kind of animals can be affected by salinity, research methods, phosphorus sources, feeding methods and so on.For example, the optimum requirement for available phosphorus of rainbow trout ranges from 0.37% (Rodkowska et al,2010) to 0.8% (Ogino & Takeda).As a euryhaline fish, spotted seabass may have different needs for P in different salinity environments.A previous study has found that the optimum dietary available phosphorus requirement for Japanese seabass reared in seawater is 0.68% (Zhang et al., 2006).Recently, Japanese seabass is identified as spotted seabass by Chen et al.(2019).However, there is no report about the dietary P requirement of spotted seabass in freshwater.In addition, the effects of dietary P levels on lipid metabolism need to be thoroughly studied.This study was designed to (a) quantify the dietary P requirement of spotted seabass cultured in freshwater and (b) explore the impacts of dietary P levels on lipid metabolism.

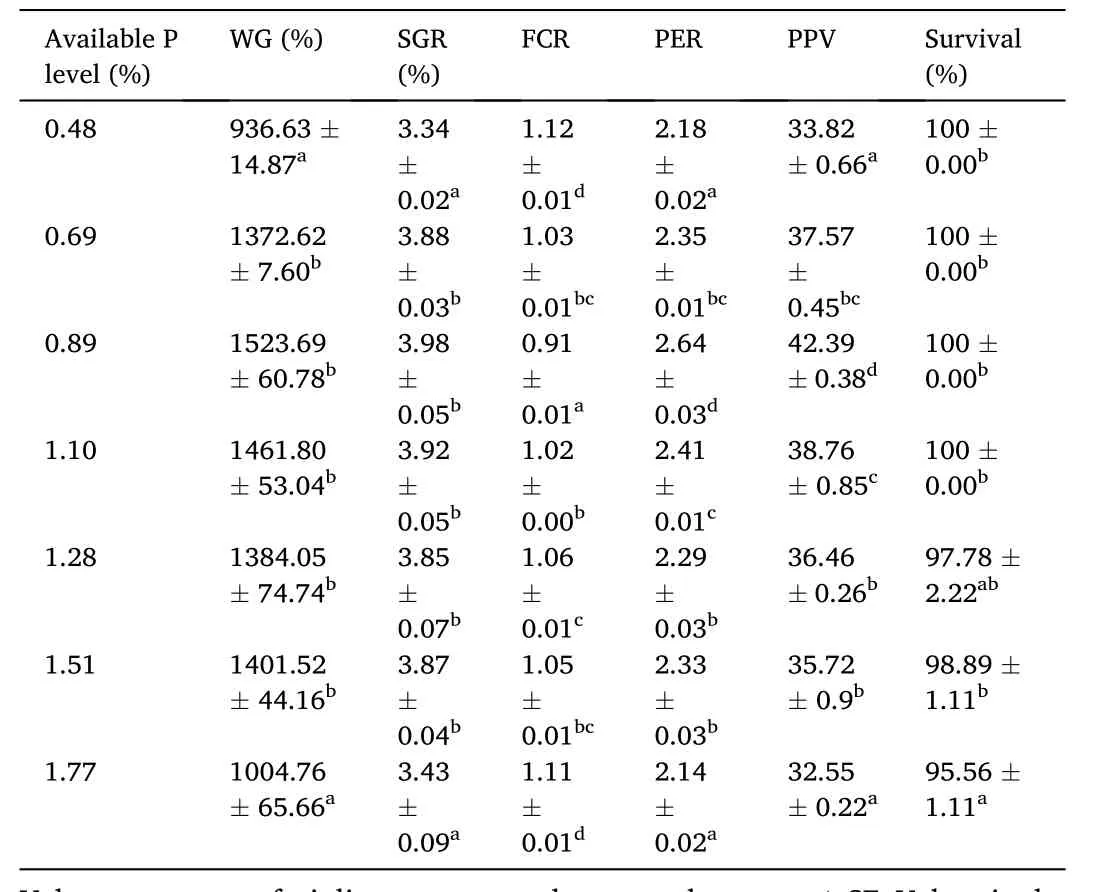

Table 3 Effects of dietary available phosphorus (P) levels on growth performance, feed utilization and survival of spotted seabass (Initial body weight: 4.26 ±0.03 g).

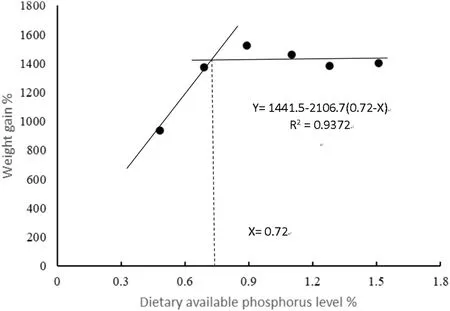

Fig.1.Broken-line regression analysis between dietary available phosphorus levels and weight gain of spotted seabass.

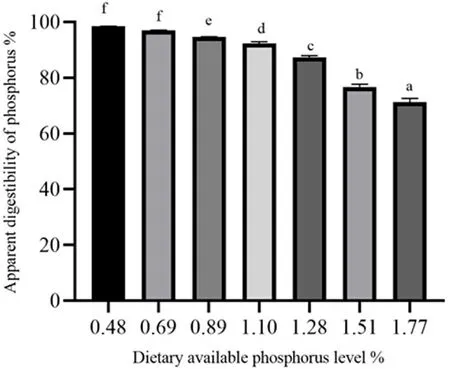

Fig.2.Apparent digestibility coefficients of P of the experimental diets for spotted seabass.

2.Materials and methods

2.1. Experimental diets

Table 1 shows the formula and general composition of the experimental diet.Seven isonitrogenous (44% protein) and isolipidic (12%lipid) experimental diets were supplemented with 0, 0.23%, 0.46%,0.69%, 0.92%, 1.15% and 1.38% P leading to dietary available P contents of 0.48% (the control group), 0.69%, 0.89%, 1.10%, 1.28%, 1.51%and 1.77%, respectively.Monosodium phosphate (NaH2PO4) and dipotassium hydrogen phosphate (K2HPO4) were used as the P sources.Ingredients of the feed were pulverized and mixed through a 60-μM sieve.Then, the oil mixture and deionized water were separately added and mixed evenly to make a dough.After the dough was made into pellets with diameters of 1.5 mm and 2.5 mm by a multifunctional spiral extrusion machinery (F-75, Guangzhou Huagong Optical Electromechanical Technology Co., Ltd., China), the pellets were dried at 45?C in an oven, then packed in sealed bags and stored at - 20?C until used.

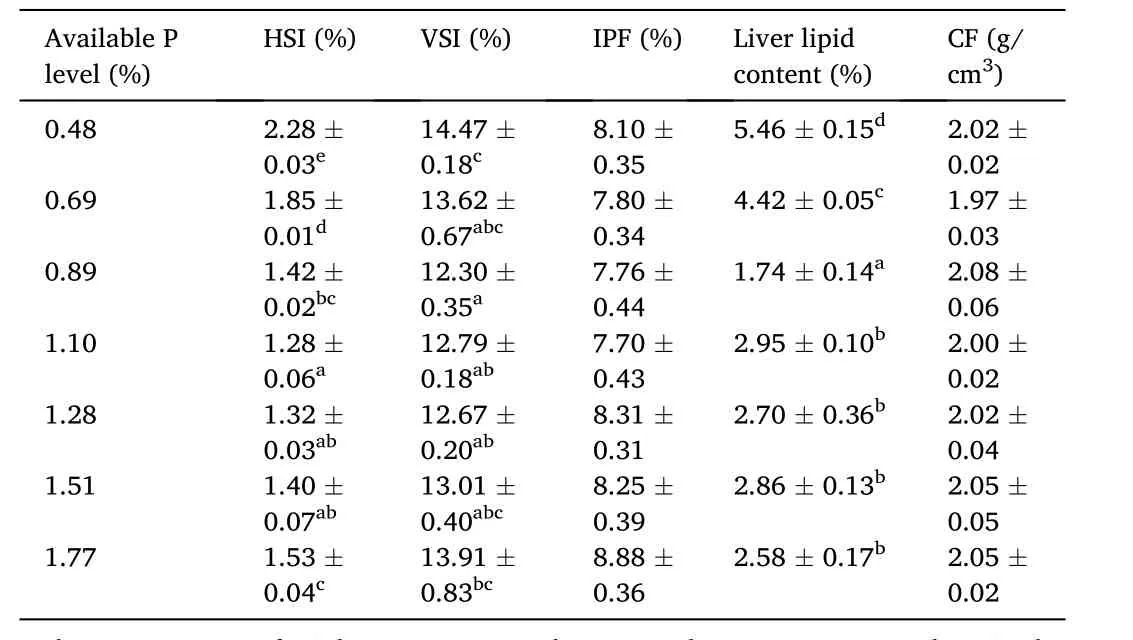

Table 4 Effects of dietary available phosphorus (P) levels on organosomatic indices of spotted seabass.

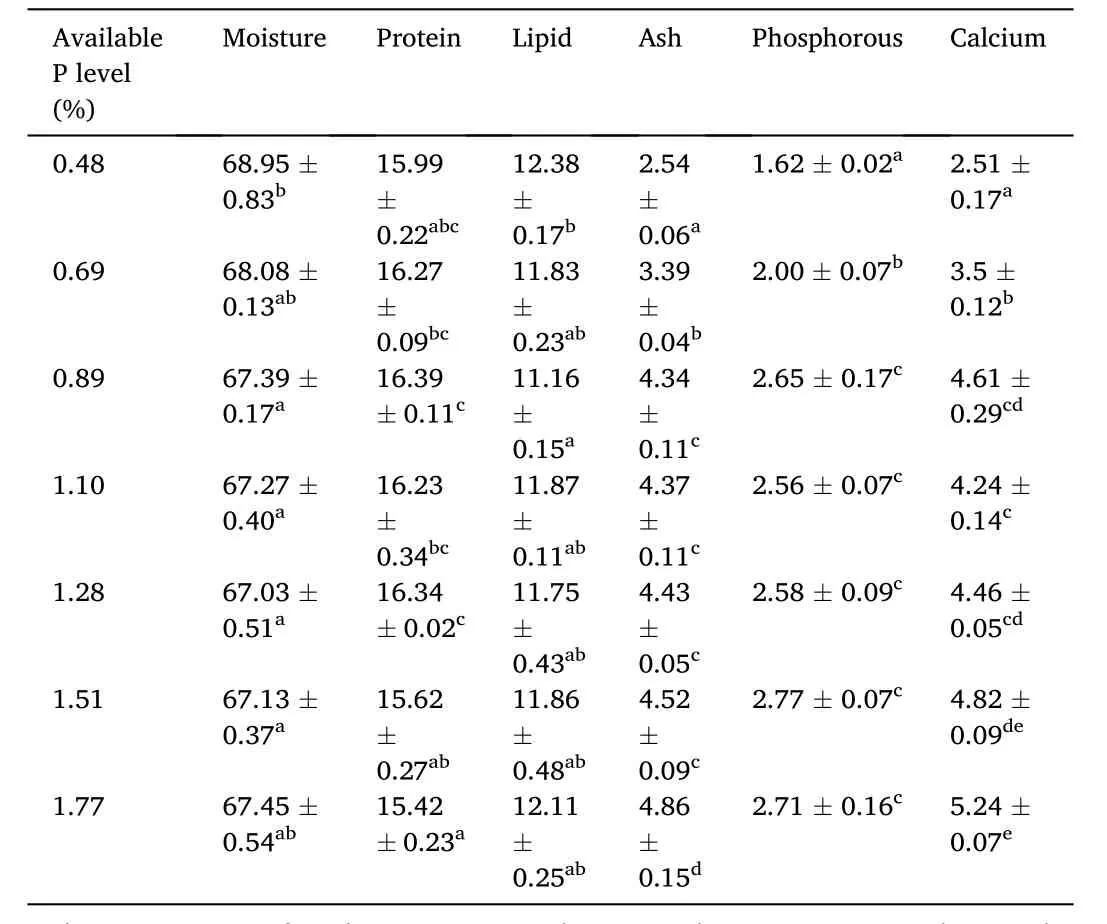

Table 5 Effects of dietary phosphorus (P) levels on whole-body composition (% wet matter) of spotted seabass.

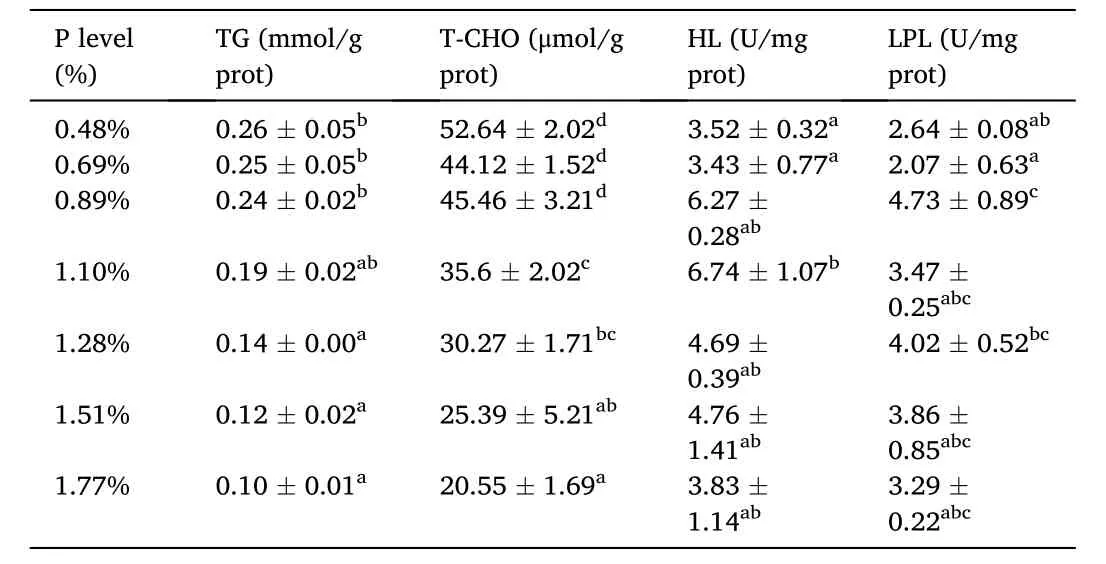

Table 6 Effects of dietary available phosphorus (P) levels on liver lipid metabolism related indices of spotted seabass.

2.2. Experimental fish and feeding trial

Experimental fish were purchased from a private farm (Nongxin Fishery Federation Information Technology Co., Ltd., Xiamen, China).The feeding trial was carried out in an outdoor recirculating system at the Institute of Animal Science of Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Guangdong, China).The fish were disinfected with potassium permanganate upon arrival to the experimental facility, then temporarily held in a circulating water system and fed a commercial diet for three weeks.Prior to initiation of the experiment, the experimental fish were temporarily raised for a week to adapted to the basal diet.During the adaptation period, the proportion of freshwater was gradually increased to fully adapt the fish to freshwater.Six hundred and thirty fish with strong physique and uniform size (4.26 ± 0.03 g) were randomly divided into 21 circular 350-L tanks containing 300 L of freshwater.The fish were fed twice (8:00 and 17:00) a day for 10 weeks until they reached a full state.After 30 min of feeding, the residual feed and feces were removed in the sink.The circulation system was turned off, and feces were collected at the defecation peak (2 h after feeding).During the feeding trial, the temperature was maintained at 28 ±1?C,dissolved oxygen level was ≥7 mg/L, pH was 7.7 ±0.1 and photoperiod was kept under natural condition.

2.3. Sample collection

Before starting the feeding experiment, 20 fish were randomly selected as the initial sample and placed at - 20?C for cryopreservation.All fish were fasted for 24 h before treatment and anesthetized with eugenol (1:10 000) before sample collection to reduce stress on the fish.To calculate growth parameters and survival rate, the number and weight of all experimental fish were recorded.Eight fish per tank were randomly captured, and their body length, individual, viscera, liver and intraperitoneal lipid were weighted.Three liver samples per tank were fixed in 10% formaldehyde solution for histological analyses.Three intact fish per tank were sampled for the analysis of whole-body composition.The remaining liver samples were used for the determination of liver enzyme activity, liver lipid content and the extraction of RNA.

2.4. Analytical methods

2.4.1.Proximate composition

According to standard procedures (AOAC, 2002), the crude lipid,crude protein, moisture and ash contents of experimental diets and whole-body samples, and liver lipid content were analyzed.Samples were chopped and dried at 105?C until constant weight was reached,then weighed to determine moisture; crude protein was measured using Auto Dumas burning nitrogen-fixation equipment (Rapid N ???, Germany); crude lipid and liver lipid content was determined by Soxhlet extraction in ether; ash content was measured by the combustion method in a muffle furnace at 550?C ± 25?C for 9 h.Mineral composition of the dietary ingredients and experimental diets, calcium and phosphorus in the whole body were determined by inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrophotometer (ICP-OES, Prodigy 7, Leeman Labs, USA).The apparent digestibility coefficients (ADCs) of the P for experimental diets were calculated using the following formula(NRC, 2011):

Table 7 Effect of dietary available phosphorus levels on liver fatty acid composition (% total fatty acids) of spotted seabass.

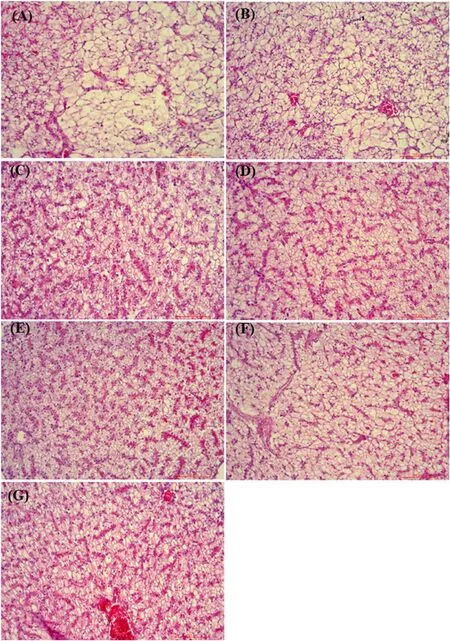

Fig.3.Effects of dietary available phosphorus levels on liver histology ( × 20) of spotted seabass (A: 0.48%, B: 0.69%, C: 0.89%, D: 1.10%, E: 1.28%, F: 1.51%,G: 1.77%).

ADC of dry matter (%) =100 - (100 ×% Y2O3in diet/ Y2O3in feces)

ADC of P (%) =100 - (100 ×% Y2O3in diet / Y2O3in feces ×% P in feces / P in diet)

Available P = Total P in diet ×ADC of P in diet

2.4.2.Histological analysis

The samples were fixed in Bouin solution for 50 h, washed three times and then stored in 70% alcohol, then cut into 1 mm3pieces.The immobilized sample was dehydrated in ethanol and dried, then quickly embedded in paraffin wax.The embedded sample was cut into 6 μm thick slices and stained with hematoxylin/eosin.Histological examination was performed with an optical microscope equipped with a digital camera and image analysis system (Leica DM5500B, China).

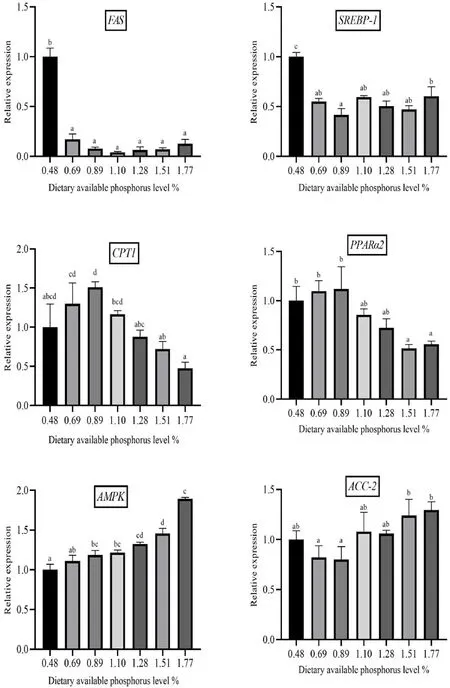

Fig.4.Relative mRNA expression of the lipid metabolism-related genes in spotted seabass fed diets with different available phosphorus levels.Bars with different letters are significantly different (P < 0.05).

2.4.3.Lipid metabolism indices

The 0.1 g of liver tissue was homogenized under ice water bath by adding 9 vol of normal saline to make a 10% tissue homogenate.The homogenate was centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was extracted.The activities of lipoprotein lipase (LPL) and hepatic lipase (HL), contents of triacyglycerol (TG) and total cholesterol(T-CHO) in liver were determined according to the commercial diagnostic kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Institute of Biological Engineering,China).The experimental procedures were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

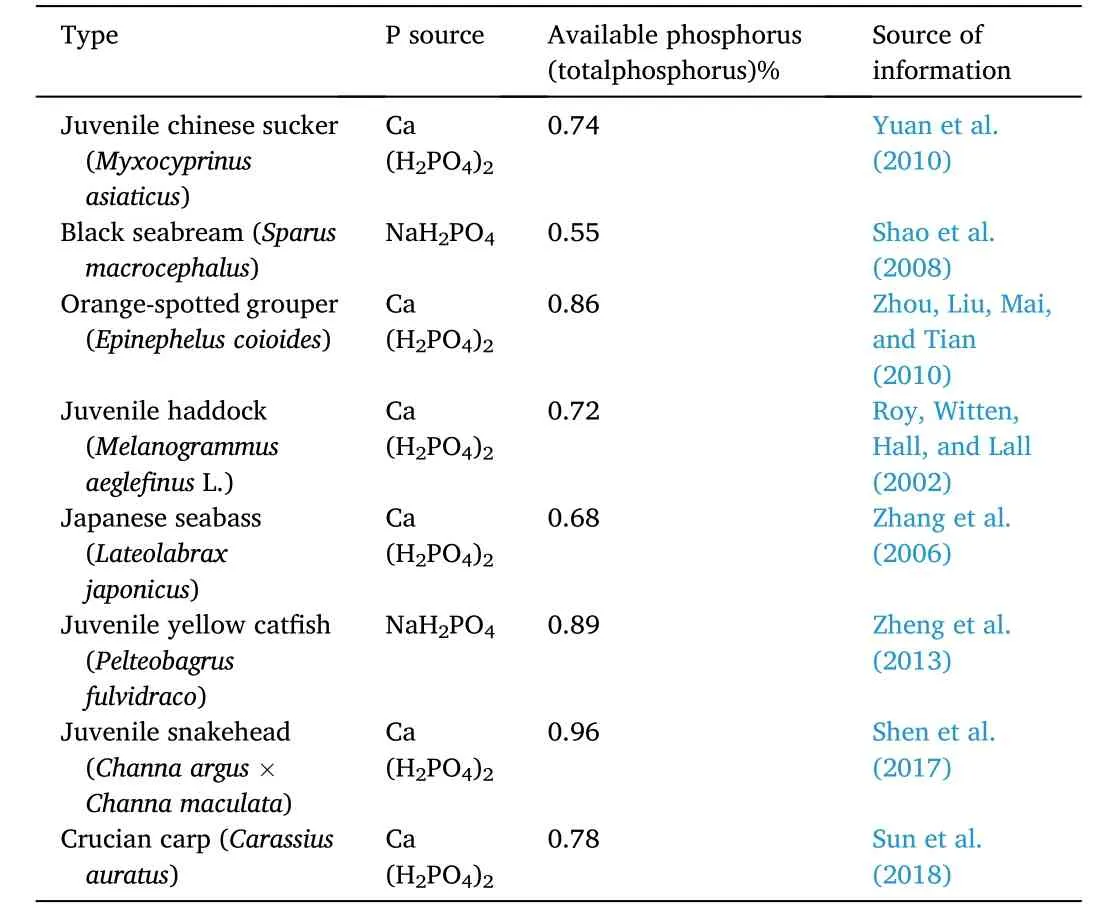

Table 8 Phosphorus requirement of fish in recent years.

2.4.4.Liver fatty acid composition

The liver fatty acid composition was assayed according to Folch, Lee,and Sloane-Stanley (1957) with some modifications.The 0.5 g liver sample was weighed, and 15 mL mixed solvent (chloroform/methanol= 2/1) was added to shake well for extracting the lipid.Then, the supernatant mixed solvent was removed to a new tube, and blowed dry under nitrogen.The precipitation of sample was extracted the lipid twice with 10 mL mixed solvent by the aforementioned procedures.After that, 2 mL of 0.5 mol/L sodium hydroxide methanol solution was added to the tube to water bath at 65?C for 30 min.After cooling, 2 mL of 25% boron trifluoride methanol solution was added to water bath at 65?C for 20 min 2 mL of n-hexane and 2 mL of saturated sodium chloride solution were added for oscillating extraction and static stratification.Fatty acid methyl esters were separated from the upper layer,and quantified by a gas chromatography (GC) (SHIMADZU2010plus,Japan).

2.4.5.RNA extraction and real-time quantitative PCR(RT-qPCR)

Fish liver samples were crushed into powder in liquid nitrogen.Total RNA was extracted from liver using Total RNA Extraction Kit (Solarbio.,Beijing).1 μg RNA was placed on 1.3% agarose gel and stained with ethyl triacetate EDTA (TAE) buffer to verify the integrity of RNA.A nucleic acid protein analyzer (NanoDrop 2000; USA) was used to detect the total RNA concentration and purity, then the reverse transcription was performed immediately with the kit from Takara.Peltier thermal circulator 200 (LongGene, A200, China) was used for incubation.1-μg cDNA was compared with 1.5% agarose gel stained with ethyl bromide to 1 ×TAE buffer to determine cDNA integrity.The total volume of PCR reaction system was 20 μL, consisting of 0.4 μL each primer, 4 μL diluted single-strand cDNA product, 10 μL 2 × PerfectStart? Green qPCR SuperMix (Transgen, China) and 5.2 μL water.The primer sequences was presented in Table 2.The RT-qPCR program was 95?C for 10 min,then 40 cycles, 95?C for 15 s, and then an extension at 60?C for 60 s.Analysis of the melting curve showed that only one PCR product existed in the reaction.The expression levels ofAMPK,SREBP-1,PPARa2,FAS,CPT-1andACC2genes were normalized toβ-actinby 2-ΔΔCTmethod.(Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).Each sample was analyzed via RT-qPCR in triplicate.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS 20 analysis software for One-Way ANOVA, and Duncan test was used for multiple comparisons.The data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SE).WhenP< 0.05, the difference was statistically significant.Broken-line model (Robbins, Norton, & Baker, 1979) was used to estimate the dietary available P requirement.The equation used in the model was L -U ×R +U ×XLR=Y, where Y was the parameter chosen to estimate the demand (WG), L was the ordinate and R is the abscissa of the breakpoint.

3.Results

The effects of different P levels on growth performance, feed utilization and survival of spotted seabass were shown in Table 3.Weight gain (WG) and specific growth rate (SGR) were significantly higher in fish fed the diets containing P levels of 0.69%–1.51% compared to fish fed the diets containing 0.48% and 1.77% P.The highest WG and SGR values were obtained at dietary P level of 0.89%, and a broken-line regression analysis based on WG revealed that the optimal P level was 0.72% of dry diet (Fig.1).Feed conversion ratio (FCR) significantly decreased as dietary P levels increased from 0.48% to 0.89% and then increased.Moreover, 0.89% dietary P level led to remarkable improvements in protein efficiency ratio (PER) and protein productive value (PPV) compared to the control group.Fish fed the diet containing 1.77% P showed significantly lower survival rate than the other groups with the exception of the fish received 1.28% dietary P.With the increase of dietary P level from 0.48% to 1.77%, the ADC of P significantly decreased (Fig.2).HSI decreased as dietary P levels increased from 0.48% to 1.10% and then increased.VSI decreased as dietary P levels increased from 0.48% to 0.89% and then increased (Table 4).In addition, liver lipid content significantly decreased with the increase of dietary P level from 0.48% to 0.89% and then showed an increasing trend.However, there was no significant difference between CF and IPF ratios among dietary treatments.

The highest whole-body protein content was found in 0.89%-P group while the lowest value was obtained in the 1.77%-P group (Table 5).Fish fed the diet containing 0.89% P exhibited drastically lower body lipid content than the control group.Also, whole-body moisture content decreased at P levels of 0.89%–1.51% compared to the control group.Moreover, whole-body ash (from 2.54% to 4.86% wet weight), P (from 1.62% to 2.71% wet weight) and calcium (Ca) (from 2.51% to 5.24%wet weight) contents increased with increasing dietary P level.

Liver TG (from 0.26 to 0.1 mmol/gprot) and T-CHO (from 52.64 to 22.55 mmol/kgprot) contents progressively decreased with the increase of the dietary P level.Liver HL activity markedly elevated with increasing P level from 0.48% to 1.10% and decreased with the further increase of P level (Table 6).Moreover, the highest liver LPL activity was determined at dietary P level of 0.89% among dietary treatments.The proportion of saturated fatty acids and mono-unsaturated fatty acids in liver decreased with increasing P levels, and the proportion was significantly lower at P levels of 0.89%–1.77% than at basal levels (Table 7).Whereas, highly unsaturated fatty acid showed an opposite trend (P<0.05), and the highest content of HUFA was obtained at P level of 0.89%.

At the basal P level (0.48%), hepatocyte cords were short and sparse,boundaries were not obvious, vacuolation was more serious, and more lipid droplets were observed in hepatocytes.While hepatocyte cords became long and dense, the vacuolation degree and lipid droplets decreased, and overall liver tissue structure improved when P level increased to 1.28%.Moreover, similar pathological signs to the P-deficient group were observed when P level increased to 1.51% and 1.77%(Fig.3).

Expression ofFASandSREBP-1was significantly higher in the 0.48%group than those in other groups (P<0.05) (Fig.4).Expression ofACC-2reached the maximum in 1.77%-P group among dietary treatments.In addition, expression ofPPARα2andCPT-1genes showed an increasing trend with the increase of P level from 0.48% to 0.89% and decreased afterward.Expression ofAMPKgene progressively increased with the elevation of P level from 0.48% to 1.77%.

4.Discussion

The broken-line regression analysis based on WG of six groups(0.48%–1.51% P) showed that spotted seabass juveniles reared in freshwater require 0.72% dietary P.The recent research results of P requirements of different fish species were shown in Table 8.Studies have shown that the P requirements of most aquatic animals are between 0.45% and 1.50% (Coote, Hone, Kenyon, & Maguire, 1996).Zhang et al.(2006) reported that P requirement of juvenile spotted seabass reared in seawater was 0.68% of diet which was lower than the estimated requirement level in the present study.Therefore, optimum P level (available P) in diets for juvenile spotted seabass in fresh water could be more than that in seawater.The differences in dietary P requirement of various fish species may be due to species differences,age, dietary composition, feeding period and rearing conditions, health status and the choice of statistical models (Avila, Tu, Basantes, & Ferraris, 2000; ElZibdeh et al., 1995; Satoh, Takanezawa, Akimoto, Kiron,& Watanabe, 2002).A significantly lower survival rate was recorded at the highest dietary P level (1.77%), probably due to poisoning of P overdose, and this group was excluded from the broken-line regression analysis for determination of the optimal P requirement level.Furthermore, P deficiency resulted in reduced growth performance and increased FCR in spotted seabass which agreed with studies on rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) (Ketola & Richmond, 1994), channel catfish(Ietalurus punetaus) (Wilson, Robinson, Gatlin, & Poe, 1982) and red sea bream (Pagrosomus major) (Sakamoto & Yone, 1978).Avila, Tu,Basantes, & Ferraris.(2000) pointed out that P deficiency promoted lipid deposition leading to the use of protein as energy source rather than being used for growth.However, increasing P intake enhanced oxidation of lipids and spared protein for tissue synthesis and growth.

Lall (1989) claimed that HSI could be used as a marker of lipid accumulation in the liver, and that P-deficient diets could promote lipid deposition.In the current study, HSI, VSI and liver lipid content decreased with increasing P levels from 0.89% to 1.10% and increased thereafter.This agreed with the results found in European white salmon(Coregonus lavaretusL.) (Vielma, Koskela, & Ruohonen, 2002), black sea bream (Sparus macrocephalus) (Shao et al., 2008) and silver perch(Bidyanus bidyanus) (Yang, Lin, Liu, & Liou, 2006).P deficiency reduced the pyruvate kinase activity which in turn interrupted the oxidative phosphorylation process and inhibited the tricarboxylic acid cycle eventually leading to enhanced lipid deposition (Onishi, Suzuki, &Takeuchi, 1981; Skonberg et al., 1997).In this study, the highest protein deposition was obtained in the 0.89%-P group probably indicating that appropriate level of dietary P could facilitate lipid used as energy source,so that dietary protein could be spared for growth.The increasing contents of whole-body ash, Ca and P by increasing dietary P content showed that P level influenced the degree of tissue mineralization.Similar findings have been reported in rainbow trout (Fontagne et al.,2009), American cichlid (Cichlasoma urophthalmus) (Chavez-Sanchez,Martinez-Palacios, Martinez-Perez, & Ross, 2000).

Liver was considered as the main organ of lipid metabolism and the main site of fatty acid oxidation (Browning & Horton, 2004).In this study, demarcation of hepatocytes was not obvious, vacuolation was serious, and greater number of lipid droplets were observed in the groups received low P diets.Similarly, a grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) study showed that P deficiency not only damaged the tight connection between cells and cell integrity but also led to liver damage by inducing increased creation of free radicals and reducing antioxidant capacity (Cheng et al., 2021) healed that the optimal dietary P level prevented lipid accumulation in hepatocytes and improved the integrity of liver tissue structure.Reduction of liver TG and T-CHO contents with increasing dietary P level in this study further confirmed the reduction of lipid accumulation in the liver which was consistent with the results of studies on taimen (Hucho taimen) (Wang, Wang, Li, Qin, & Yin, 2017)and black seabream (Shao et al., 2008).Moreover, increasing dietary P level in this study promoted liver HL and LPL activities.Yang, Lin, Liu,and Chen (2014) declared that reducing lipid accumulation in the liver was the most efficient way of lowering the risk of liver diseases.P combined with lipids to form phospholipids, which contributed to dissolution and absorption of lipids and played key roles in lipid metabolism (Roy & Lall, 2003).Thus, incorporation of an appropriate amount of P in diets for aquatic animals was essential for maintenance of the lipid metabolism.

Studies on broiler chickens have shown that higher fatty acid content is found in breast meat of broilers fed low P diet, and that high P diet may affect SFA and HUFA of broilers (Li et al., 2016).The results of this study showed that increasing P level could enhance the hepatic HUFA ratio and reduce the ratio of SFA to MUFA.HUFA could increase fatty acid β oxidation and decrease lipid synthesis (Du et al., 2006), which could explain the significant decrease of liver lipid content with increasing dietary P level to 0.89%.

Increasing dietary P level led to the up-regulated mRNA expression ofAMPK.Miao et al.(2017) reported that the lack of P resulted in decreased phosphorylation level ofAMPKandACC.Therefore, P could inhibit lipid formation with enhancingAMPKphosphorylation thus reducing the deposition of lipids in the muscle (Li et al., 2016).In this study, mRNA expression ofACC-2decreased at 0.89-P group and thereafter an increasing trend was observed.This might indicate inhibition ofACC-2phosphorylation at low P levels causing its increased mRNA expression level.Moreover,PPARα2played an important role in hydrolysis of triglyceride and phospholipid (Cunha et al., 2013).Expression ofPPARα2mRNA increased with increasing dietary P level from 0.48% to 0.89% which was consistent with the observed trend forCPT-1 mRNA expression.Furthermore, activatedPPARαcould catalyze the synthesis of LPL, so that LPL could catalyze the hydrolysis of lipids to free fatty acids (Rudkowska et al., 2010).Moreover,PPARα2induced the expression ofCPT-1in the liver, stimulated β oxidation and reduced the synthesis of fatty acids (Tian et al., 2018).LPL was not only a rate-limiting enzyme for the degradation of TG into glycerol and fatty acids but also acted as a key enzyme in regulating lipid metabolism and lipid deposition (Zhang et al., 2020).Likewise, our results showed that TG and LPL exhibited opposite trends in the liver, which suggested that 0.48% P level attenuated seabass hepatic lipolysis.

SREBP-1was an important transcription factor in regulating lipid metabolism (Wang et al., 2015).FAS was the only enzyme that could synthesize long-chain fatty acids from scratch (Kuhajda et al., 1994),and could change the rate of synthesis and hydrolysis of fatty acids(Smith, Witkowski, & Joshi, 2003).The results of this experiment showed down-regulated expression ofFASandSREBP-1with increasing dietary P levels.Likewise, Ji et al.(2017) reported the decreased expression ofFASandSREBP-1in catfish fed diets containing 1.32% and 1.59% P compared to 1.12% P.In NAFLD mice, the activity of theSREBP-1cwas shown to be significantly increased (An et al., 2019), and to contribute to the liver lipid deposition.There were studies showed that the degree of hepatic steatosis of obese mice was lowered afterSREBP-1activity was inhibited (Jiao et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2010; Yan et al., 2014).Studies in spotted seabass showed that increasing P level led to decreased mRNA expression level ofFAS(Lu et al., 2017).Therefore, increasing the level of P could inhibit lipid synthesis.

5.Conclusion

The current study showed that appropriate dietary P level could promote growth performance of spotted seabass and reduce lipid accumulation in the liver.The optimum P level in diets for spotted seabass juveniles cultured in freshwater was suggested to be 0.72% of dry diet based on weight gain.The results of this study provided theoretical support for the efficient utilization of dietary P, and laid a foundation for the development of fish environment-friendly feed.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Jimei University, Xiamen, Fujian Province, China.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jilei Zhang:Formal analysis, Writing – original draft.Shuwei Zhang:Formal analysis, Investigation.Kangle Lu:Resources, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.Ling Wang:Investigation, Writing –review & editing.Kai Song:Resources, Writing – review & editing.Xueshan Li:Writing – review & editing.Chunxiao Zhang:Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.Samad Rahimnejad:Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 31972804) and the China Agricultural Research System (grant number: CARS47-14).We thank Dr.Guoxia Wang for her valuable help for feeding trial.

Aquaculture and Fisheries2023年5期

Aquaculture and Fisheries2023年5期

- Aquaculture and Fisheries的其它文章

- The effectiveness of light emitting diode (LED) lamps in the offshore purse seine fishery in Vietnam

- Immunomolecular response of CD4+, CD8+, TNF-α and IFN-γ in Myxobolus-infected koi (Cyprinus carpio) treated with probiotics

- Effects of transport stress on immune response, physiological state, and WSSV concentration in the red swamp crayfish Procambarus clarkii

- Expression of gastrin and cholecystokinin B receptor in Lateolabrax maculatus

- The first draft genome assembly and data analysis of the Malaysian mahseer(Tor tambroides)

- The competitiveness of China’s seaweed products in the international market from 2002 to 2017