Effects of transport stress on immune response, physiological state, and WSSV concentration in the red swamp crayfish Procambarus clarkii

Ruixue Shi, Siqi Yang, Qishuai Wang, Long Zhang, Yanhe Li

College of Fisheries, Key Laboratory of Freshwater Animal Breeding, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affair/Engineering Research Center of Green Development for Conventional Aquatic Biological Industry in the Yangtze River Economic Belt, Ministry of Education, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, 430070, China

Keywords:Transport stress Crayfish Oxidative stress Hepatopancreas Serum White spot syndrome virus

A B S T R A C T Transport is an essential part of the aquaculture and research of the main freshwater aquaculture crayfish Procambarus clarkii in China.However, transport is often accompanied by a low survival rate.Assessing the physiological state of P. clarkii before and after transport may discover the cause of this high mortality rate.In this study, ice-cold and exposed-to-air transport methods were compared using an array of parameters, including relative expression level of heat shock protein 70 (HSP70), content of serum glucose and cortisol, immune parameters (enzyme and immune-related genes), and white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) concentration were investigated to understand the physiological state of P. clarkii before and after transport, as well as the cause of dying crayfish on days 5 and 7 after transport stress.Histological sections of hepatopancreas, gills, and intestines reflected pathological changes.The survival rate of crayfish with ice-cold transport was significantly higher than that with exposed-to-air transport, and mortality peaked at 3–9 days after transport stress.A prolonged response to oxidative stress and short-term immunosuppression was present after transport, and the trend of the WSSV concentration in the hepatopancreas was similar to the mortality rate of P. clarkii. The contents of serum glucose and cortisol, antioxidant enzymes and immune-related indexes, and the concentration of WSSV in hepatopancreas of dying crayfish were significantly higher than those of vibrant crayfish on the 5th and 7th days after transport.The hepatopancreas, intestines, and gills of dying crayfish had varying degrees of damage, and the hepatopancreas and intestines were severely damaged.The results suggested that the death of P. clarkii after transport stress is caused by oxidative stress, the imbalance of reactive oxygen species regulation, and decreased WSSV resistance, which eventually led to irreversible tissue damage.The increase of WSSV in the body of crayfish might be the direct cause of crayfish death.

1.Introduction

Procambarus clarkiihas become an important aquatic commercial species in China with extensive aquaculture supply and demand (Jin et al., 2019).Transport is an essential part of aquaculture, yet, the survival rate ofP.clarkiiis often too low for culture or breeding processes after more than 2 h of transport stress (Guan, Chen, Hong, & Sun, 2015),especially in summer (Bian, 2010).Interestingly, mass mortality usually occurs about one week instead of 2–3 days after transport, before stabilizing after about two weeks.Farmers suffer large economic losses due to mortality after transport, which affects the sustainable and healthy development of the crayfish industry (Li, 2020).

In the process of transport and the early stage of aquatic culture after transport, there are various environmental stress factors, including air exposure, handling, physical disturbance, temperature, pH fluctuation,salinity changes, and high levels of dissolved ammonia (Fotedar &Evans, 2010).These factors impact the normal physiological state of aquatic animals, causing the body to produce stress and immune responses (Moullac & Haffner, 2000; Fotedar & Evans, 2010; Souza et al.,2013; Hvas & Oppedal, 2019; Guo et al., 2020).The low survival rate after transport stress is usually attributed to the stress response caused by exposure to adverse environmental conditions or physical treatment(Fotedar & Evans, 2010; Sun et al., 2020).At the same time, environmental stress is closely related to immune response (Chen & He, 2018).Long-term exposure to stress accelerates the oxidative stress of hepatopancreas and seriously damages the immune system of aquatic animals,even directly causing the death of aquatic animals shortly after transport(Fotedar & Evans, 2010; Hvas & Oppedal, 2019; Sun et al., 2020).

White spot syndrome virus (WSSV), which is widely present inP.clarkii, is the most serious viral pathogen of farmed crustaceans(Zhang, Li, Wu, Ouyang, & Shi, 2020).White spot disease, caused by WSSV, has caused huge economic losses to the global crustacean farming industry (Liu, Liu, Li, & Liu, 2021).Changes in salinity within a specific range can reduce the immune capacity ofFenneropenaeus chinensisand are accompanied by WSSV proliferation (Liu et al., 2005).Variations in ammonia and pH beyond the normal range also significantly increase the susceptibility to WSSV forPenaeus vannamei(Kathyayani, Poornima,Sukumaran, Nagavel, & Muralidhar, 2019).It has been reported that WSSV is closely related to environmental stress (Chen & He, 2018).

We hypothesized that the low survival rate ofP.clarkiiduring the early stage of culture after transport stress presently might caused by the psychological imbalances and the increased concentration of WSSV due to transport and environmental stress.To explore the direct cause of the low survival rate ofP.clarkiiafter transport, the changes of stress and immune-related enzyme indexes, related gene expression levels, hepatopancreas, intestinal and gill histopathology, and WSSV proliferation before and after transport were investigated.

2.Material and methods

2.1. Experimental crayfish preparation and sample collection

The 800 adultP.clarkii(average weight 29.32 ± 4.48 g) were collected from a crayfish farm in Honghu City, Hubei Province, in early August.Two modes of transport were adopted: ice-cold transport (2 foam boxes of 400 mm ×350 mm ×260 mm with ice bag in the middle)and exposed-to-air transport (3 plastic baskets of 400 mm ×310 mm ×235 mm), each of which transported 400 crayfish during the 2 h 58 min(from 8:10 am to 11:08 am) journey.After transport, crayfish from each mode of transport were randomly divided into two subgroups, maintained in ponds (2 m × 4 m, 200 crayfish each pond) with water temperatures 29 ± 2?C, and fed with a commercial pelleted feed once per day.The deaths ofP.clarkiiwere recorded daily up to 14 days after transport.

The tissue samples (hepatopancreas, heart, and hemolymph) were collected before transport (denoted by “0” below) and at the 1st, 3rd,5th, 7th, and 14th days of culture after transport.Six crayfish were sampled from each group at each sampling time.The heart and hepatopancreas samples were collected into a cryopreservation tube that was stored in liquid nitrogen immediately.The hemolymph (about 1 mL)was extracted from the pericardial sinus ofP.clarkiiwith a 1 mL disposable sterile syringe and refrigerated at 4?C overnight.The hemolymph was then centrifuged at 5000 r/min at 4?C for 10 min in a refrigerated centrifuge, and the supernatant (serum) was removed into a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube for subsequent experiments (Chen, Zhuang, et al.,2019).

A large number of crayfish deaths occurred on the 5th and 7th day after transport stress.To further explore the physiological state and WSSV infection of crayfish, 3 dying crayfish (crayfish with very low motor activity) were sampled from each group at these 2 days using the same sampling and detection methods as described above.Additionally,the intestines, gills, and hepatopancreas of these 3 dying individuals and vibrant crayfish (crayfish with normal motor activity) were selected on the 5th and 7th day, and fixed in universal tissue fixative (Servicebio,Wuhan, China) for 24 h of fixation at room temperature.

2.2. Determination of serum glucose and cortisol level

Cortisol and glucose contents were determined as biological indicators to assess stress levels (Jiang, 2015) with a Shrimp Cortisol Elisa Kit and a Glucose Determination Kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Institute of Biological Engineering, China).

2.3. Activity assay of immune-related enzymes in serum and hepatopancreas

The hepatopancreas were homogenized with 0.65% sterile saline solution to prepare 10% (w:v) homogenates, centrifuged at 4000 r/min for 10 min at 4?C, and preserved the supernatant.The concentration of proteins in the supernatant was detected by BCA Protein Quantification kit (Yeasen, Shanghai, China).The serum sample collected in Section 2.2 was used for testing immune-related enzyme activities.The immunerelated enzyme activities in serum and hepatopancreas such as catalase (CAT), acid phosphatase (ACP), total superoxide dismutase (SOD),and serum lysozyme (LZM) were measured according to a commercial kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China).

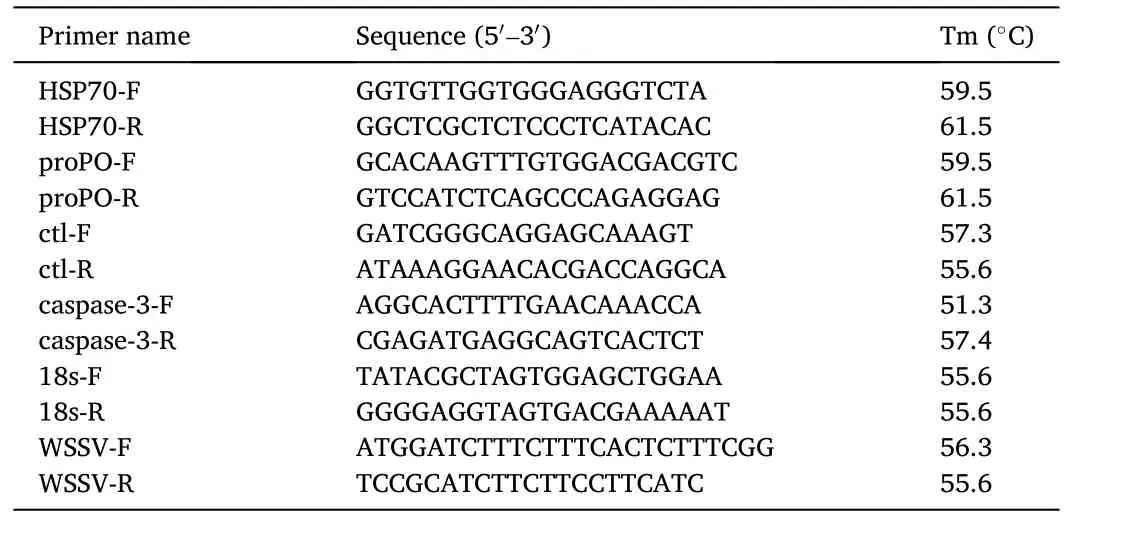

2.4. Quantification of ctl, proPO, caspase-3 and HSP70 gene expression

The total RNA from the heart and hepatopancreas was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA).The cDNA was synthesized using PrimeScriptTMRT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa, Dalian,China).The RT-qPCR reaction was carried out with 20 μL, including 10 μL SYBR Green master mix (Takara, Dalian, China), 1 μL cDNA, 0.2 μL each of primers (Table 1) and 8.6 μL ddH2O.18S RNA was amplified as a housekeeper gene using the same amplification procedure.The expression level ofctl,proPO,caspase-3, andHSP70were determined by the 2-ΔCtmethod (Zhang, Li, et al., 2020).Experiments complied with the MIQE guidelines (Bustin et al., 2009).

2.5. Detection of the WSSV concentrations

The genomic DNA of the hepatopancreas was extracted using the modified proteinase K/ammonium acetate extraction protocol (Li et al.,2011).The primers for amplifying WSSV are shown in Table 1 and the amplification procedure was: 95?C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95?C for 15 s, 60?C for 30 s and 72?C for 30 s.The target PCR products were cloned into PMD-18-T (Takara, Dalian, China) and then used to transformE.coli(DH5α).The plasmid PMD-18-T-WSSV was extracted and used as the calculation standard for the absolute quantity of virus in each tissue replicate.The WSSV concentration within the plasmid solution was calculated by the formula: (6.02 × 1023× ng/μL ×10-9)/DNA length ×660 =copies/μL (ng/μL refers to the concentration of the plasmid PMD-18-T-WSSV, the DNA length refers to the number of base pairs of the plasmid PMD-18-T-WSSV).The plasmid with known WSSV concentration was sequentially diluted ten-fold as the template of RT-qPCR.RT-qPCR was performed to construct the standard curve of the CT value (x-axis) and the logarithmic value of the WSSV concentration(y-axis).The WSSV concentration was calculated in each sample according to the standard curve.

2.6. Histological observation of hepatopancreas, gills and intestines

The intestine, gill, and hepatopancreas samples fixed in universaltissue fixative (Servicebio, Wuhan, China) were dehydrated in graded serial ethanol, made transparent in xylene, and embedded in paraffin.The tissue sections were sliced to 4 μm and stained by hematoxylin and eosin (H & E).The sections were examined with a microscope (Nikon,China).Pathology was divided into 4 categories according to the fields,(- ), (+), (+ +), and (+ + +), which successively represent to no pathology, pathology in <30% of fields, pathology in 30–70% of fields,and pathology in >70% of fields (Stara, Kouba, & Velisek., 2018).

Table 1 Primer sequences for qPCR in this study.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SD.The charts were prepared in GraphPad Prism 7 software (GraphPad Software, Inc, USA).The software SPSS 23.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics 23) was used for the statistical analysis.Normality was checked using the Shapiro-Wilk test for all data before analysis.One-way ANOVA was used for data with normal distribution.Otherwise, non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests were performed.Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed to assess the difference of the survival rate in ice-cold transport group and exposed-to-air transport group.P< 0.05 was considered to be significant, andP< 0.01 was highly significant.

3.Results

3.1. Survival rate

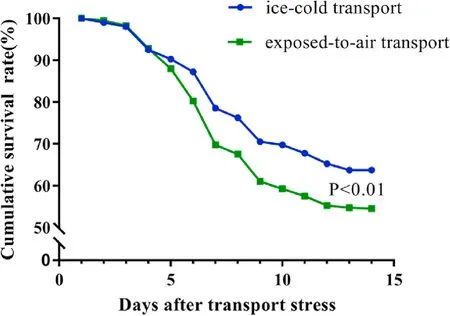

The cumulative survival rate ofP.clarkiiduring the 14 days after icecold transport and exposed-to-air transport was recorded (Fig.1).The peak in mortality ofP.clarkiiwas from 3 to 9 days after transport stress.After 14 days of culture, the cumulative survival rate was 63.75% in the ice-cold transport group and 54.5% in the exposed-to-air transport group.The cumulative survival rate was significantly higher in the icecold transport group compared to the exposed-to-air transport group (P<0.01).

3.2. Stress response of P. clarkii before and after transport

The stress response ofP.clarkiibefore and after transport were measured via the changes of serum glucose and cortisol contents, and the relative expression level of heat shock protein (HSP70) (Fig.2).The glucose content ofP.clarkiisignificantly decreased on the 14th day of culture compared to all other groups.As with glucose, cortisol levels were significantly lower at 14 days in the ice-cold transport group, while there was no significant change in cortisol content in the exposed-to-air transport group.The relative expression levels ofHSP70gene in ice-cold and exposed-to-air group both decreased significantly on the 3rd day,and then recovered to a higher level.

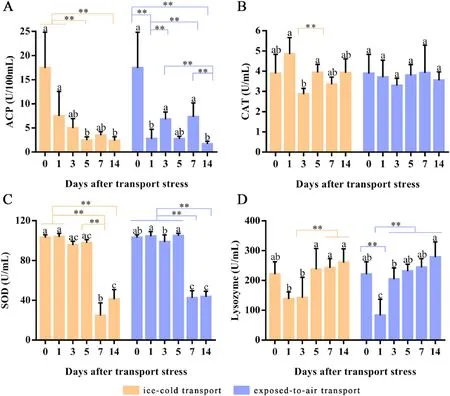

3.3. Effects of transport stress on the expression levels of immune-related enzymes and genes in P. clarkii

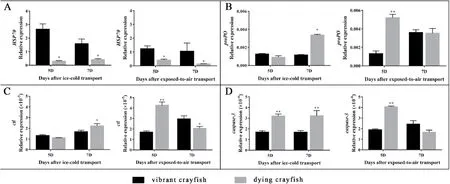

The changes in ACP, CAT, SOD, and LZM activities in serum (Fig.3)and ACP, CAT, and SOD activities in hepatopancreas (Fig.4), as well as the expression levels of 3 immune-related genes (Fig.5) reflected the antioxidant and immune responses ofP.clarkiiafter 2 modes of transport.

Fig.1.The cumulative survival rate of P. clarkii (400 individuals per group) cultured in 14 days after being transported with ice-cold and exposed-to-air.

Fig.2.Changes in serum glucose (A) and cortisol content (B), and the relative expression of HSP70 (C) in the heart of P. clarkii before transport stress and during the cultured 14 days after ice-cold and exposed-to-air transport stress.All data were expressed as mean ± SD, n = 6.The different letters on the same color column indicate significant difference (P < 0.05).** indicates highly statistical significance that P-values less than 0.01.

Fig.3.The activities of ACP (A), CAT (B), SOD (C) and LZM (D) in serum of P. clarkii before transport and during the cultured 14 days after ice-cold and exposed-toair transport.All data were expressed as mean ± SD, n = 6.The different letters on the same color column indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05).** Highly significant difference.

Fig.4.The activities of ACP (A), CAT (B) and SOD (C) in hepatopancreas of P. clarkii before and after transport with ice-cold or exposed-to-air.The different letters on the same color column indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05).** Highly significant difference.Data were shown as mean ± SD, n = 6.

Fig.5.Relative expression levels of immune-related genes proPO (A), ctl (B) and caspase-3 (C) in hepatopancreas of P. clarkii before and after transport stress.Bars represent the means of 3 individual mean ± SD.The different letters on the same color column indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05).** Highly significant difference.

The serum ACP activity ofP.clarkiidecreased gradually before and after ice-cold and exposed-to-air transport, stabilizing at about 2 U/100 mL, which was significantly different from before transport (Fig.3A).There was no significant difference of CAT activity in serum before and after exposed-to-air transport.After ice-cold transport, CAT activity reached the lowest level on the 3rd day (Fig.3B).The SOD activities of the 2 groups were higher at the period of transport before and within 5 days after transport than other days, and decreased significantly on the 7th, and 14th day after transport (Fig.3C).After transport, the lysozyme activities of the 2 groups decreased significantly on the 1st day of culture, while the ice-cold transport group remained a low level on the 3rd day, the activities of the exposed-to-air transport group were increased.In both groups, the lysozyme activities on the 5th, 7th, and 14th day of culture had no significant difference compared with that before transport (Fig.3D).

The ACP activity of hepatopancreas in both groups reached the lowest level on the 1st day of culture compared with before transport,and increased on the 3rd day, then gradually stabilized at about 100 U/mgprot (Fig.4A).The CAT activity in hepatopancreas showed a gradually increasing trend before and after transport in both groups(Fig.4B).The activity of SOD in hepatopancreas ofP.clarkiiin both groups first increased, reached the highest level on the 5th day, and then gradually trended to be stable (Fig.4C).

The expression level of immune-related geneproPOin hepatopancreas was significantly decreased on the 3rd day after transport stress,and then increased.The relative expression level ofproPOin the ice-cold transport group was not significantly different from that before the transport, and the relative expression level ofproPOin the exposed-toair transport group on the 7th and 14th day was significantly higher than that before the transport (Fig.5A).Expression level ofctlgene in hepatopancreas significantly decreased on the 1st day, and then increased on the 3rd day.The relative expression level ofctlgene in icecold transport group was significantly decreased on the 14th day, while significantly increased in air-exposure transport group compared with that on the 7th day (Fig.5B).A significant decrease ofcaspase-3level on the 3rd day and a higher expression level on 5th and 7th days was found in both groups.On the 14th day, the relative expression level ofcaspase-3gene was highly significant decreased compared with it on the 7th days in ice-cold transport group, while increased significant in exposedto-air transport group.

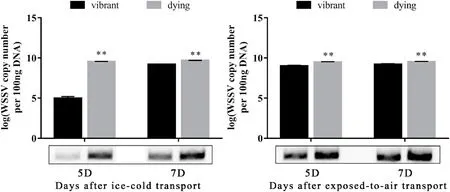

3.4. Changes in the concentration of WSSV within hepatopancreas

The concentration of WSSV in hepatopancreas was detected by RTqPCR (Fig.6).In the ice-cold transport group, the concentration of WSSV on the 3rd and 7th day after transport was higher than other days,and the concentration of WSSV on the 14th day was not significantly different from before transport (Fig.6A).In the exposed-to-air transport group, the concentration of WSSV on the 5th and 7th day was higher than other days, and the concentration of WSSV on the 14th day decreased, but there was no significant difference compared with before transport (Fig.6B).

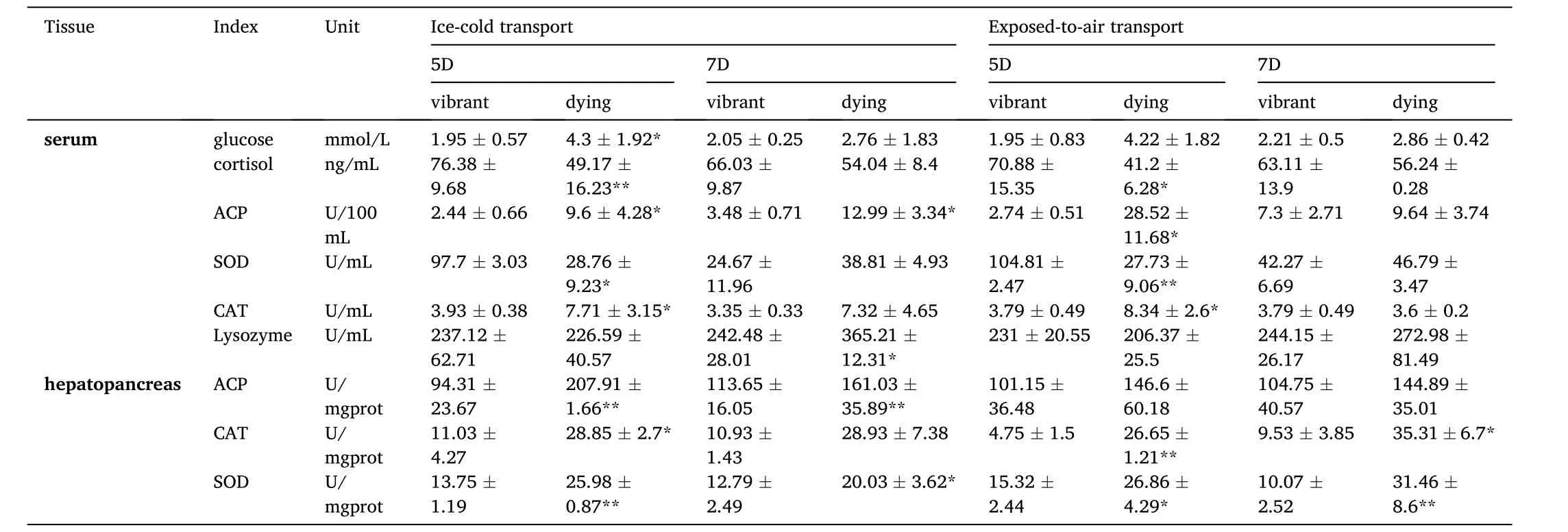

3.5. Comparison of physiological state between dying and vibrant crayfish

The crayfish were dying in large numbers on the 5th and 7th days of the experiment.To explore the physiological state of dyingP.clarkii, the vibrant and dying crayfish samples collected on the 5th and 7th days were detected the stress and immune indicators, including the expression of some stress- and immune-related genes, WSSV concentration,and histopathological changes.

Fig.6.The changes of WSSV concentration in hepatopancreas before and after transport with ice-cold (A) or exposed-to-air (B).Bars represent the means of 3 individual mean ± SD.Different letters indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05).** Highly significant difference.

Compared with vibrant crayfish, the serum glucose content of dying crayfish significantly increased, the cortisol content decreased, and the ACP, CAT, SOD activities in serum and hepatopancreas of dying crayfish were higher, while the difference of serum lysozyme was not significant(Table 2).The relative expression ofHSP70gene in the heart of dying crayfish was significantly lower than that of vibrant crayfish (Fig.7A).The relative expression of immunity-related genesproPOandctlin hepatopancreas were higher than that of dying crayfish, and the relative expression ofcaspase-3gene in hepatopancreas was significantly higher than that in vibrant crayfish (Fig.7).The concentration of WSSV of dying crayfish in the two groups was significantly higher than that of vibrant crayfish (Fig.8).

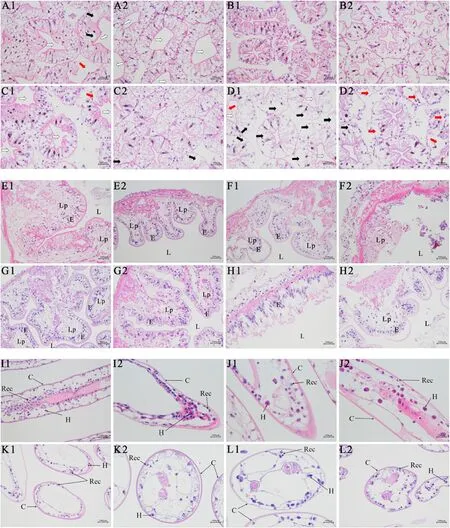

The hepatopancreas of crayfish with normal vitality on the 5th and 7th day after transport showed tubule lumen dilatation (+ + +),vacuolation (+ +) and some hepatic tubules moderate damage (+)(Fig.9A1-2, Fig.9C1-2).On the 5th day, hepatopancreas of dying crayfish exhibited partial connections between hepatic tubules fade away (+ + +) (Fig.9B1), necrotic and dissolved of hepatic cells (+ ++), and the number of cells significantly reduced (+ + +) (Fig.9B2).The severe vacuolation (+ + +) (Fig.9D1) and damage of hepatic tubules (+ + +) (Fig.9D2) were observed in dying crayfish on the 7th day.The normal vitality crayfish on the 5th and 7th day had normal intestinal tissue structure, tight lamina propria, orderly lamina epithelialises, and normal cell palisade arrangements (- ) (Fig.9E1-2,Fig.9G1-2).While histological anomalies of intestinal were apparent in dying crayfish (+ + +), as atrophy of connective tissue, extensive cracks between tissues, abnormal palisade-arranged of epithelial cells(Fig.9F1, Fig.9H1-2), intestinal epithelial tissue broke away from connective tissue, epithelial cell necrosis, and nucleus scattered in the intestinal cavity (Fig.9F2).Gills showed abscission of respiratory epithelium cells (Fig.9I1-L2).The corneum of vibrant crayfish was smooth and complete (- ), while the corneum of dying crayfish was tortuous (Fig.9L1) and partially ruptured (+) (Fig.9L2).Large areas of respiratory epithelium cells of dying crayfish were abscission and necrosis, scattered in microvascular lumen, and the number of cells was significantly reduced (+ + +) (Fig.9J2).

Table 2 Immune and stress response parameters in serum and hepatopancreas.

Fig.7.Comparison of the relative expression levels of HSP70 (A) gene in heart, proPO (B), ctl (C), and caspase-3 (D) genes in hepatopancreas of vibrant crayfish and dying crayfish on 5th and 7th day after transport.“*” indicates significant difference (P <0.05) and “**” noted highly significant difference (P <0.01) on the same day within the same group.Bars represent the means of 3 individual mean ± SD.

Fig.8.The WSSV concentration of vibrant and dying crayfish on the 5th and 7th day after transport under ice-cold (A) and exposed-to-air (B).“*” indicate significant difference (P < 0.05) and “**” indicate highly significant difference (P < 0.01) on the same day within the same group.Bars represent the means of 3 individual mean ± SD.

4.Discussion

Transport stress refers to many stress factors that affect the normal physiological state of animals.P.clarkii, the main freshwater aquaculture crayfish in China, has a rich yield.With the development ofP.clarkiiindustry, transport with a high survival rate is very important for its aquaculture.Studies increasingly focus on the influence of stress factors,including temperature shock, hypoxia stress, continuous shaking, et cetera (Souza et al., 2013; Powell, Cowing, Eriksson, & Johnson, 2017;Guo et al., 2020).It is difficult to predict the influence of transport stress,which is involved in the numerous stress factors (Obernier & Baldwin,2006).However, it is an efficient way to reveal the cause of death by discovering the change of physiological state after transport stress.In the present study, the physiological state of the crayfish was investigated to explore the main cause of the low survival rate ofP.clarkiiafter two transport methods.

Ice-cold transport and exposed-to-air transport are both commonly used in crayfish aquaculture and the results showed that the survival rate was significantly higher in ice-cold transport group.Of exposed-toair transport, aquatic animals endured water shortage and hypoxia,which induced apoptosis of hepatopancreas and gill cells ofMarsupenaeus japonicus(Wang, Wang, Su, Liu, & Mao, 2020), led to high mortality of mud crabs (Cheng, Ma, Deng, Feng, & Guo, 2019).Farfantepenaeus brasiliensisjuveniles at a lower temperature during transport had higher antioxidant capacity (Souza et al., 2013), which was consistent with the results of this study.For both transport methods,mortallity rates peaked on the 3rd to 9th day after transport stress,especially on the 5th to 7th day and then gradually stabilized.

Transport stress can trigger a series of stress responses that make the physiological state of the body change (Fazio, Medica, Aronica, Grasso,& Ferlazzo, 2008; Souza et al., 2013; Pascual-Alonso et al., 2017; Hunt,Innis, Merigo, & Buck, 2018).These physiological changes are often reflected by sensitive indicators, such as the glucose and cortisol levels,which are associated with stress intensity in crustaceans (Banaee et al.,2019; Jiang, 2015; Si, Pan, Zhang, Wang, & Wei, 2019).HSP70, also known as stress protein, is one ofHSPfamily that has received the most attention, and can be used as a molecular biomarker for stress response and evaluation of tissue cells in danger state (Baringou et al., 2016).It is widely distributed in the tissues ofP.clarkii, among which the expression is higher in the heart (Sun, Zhang, Li, Wu, & Xie, 2009).The relative expression level ofHSP70gene increased significantly on the first day after transport, which could increase cell resistance to stress (Dalvi et al.,2017).The glucose levels increased, which might provide energy for metabolic demands after transport stress.In the present study, serum glucose and cortisol contents were both at a higher level before and within 7 days after transport stress.The prolonged response to oxidative stress may be related to the death ofP.clarkii.

Fig.9.Paraffin sections observation of hepatopancreas (A1-D2), intestines (E1-H2) and gills (I1-L2) of vibrant and dying crayfish on the 5th and 7th day after transport.A1-A2, E1-E2, I1-I2, and C1-C2, G1-G2, K1-K2, present the sections observation of hepatopancreas, intestine, and gill of vibrant crayfish on the 5th and 7th day respectively; B1-B2, F1-F2, J1-J2, and D1-D2, H1-H2, L1-L2, showed the sections observation of hepatopancreas, intestine, and gill of dying crayfish on the 5th and 7th day respectively.L, lumen; E, epithelium; Lp, lamina propria; C, corneum; H, haemocoele cells; Rec, respiratory epithelium cells.The tubule lumen dilatation was marked by black-edged white heart arrows; vacuolization was marked by black arrows; incomplete hepatic tubules was marked by red arrows.H&E stain.

The environmental stress can induce the production of ROS (Duan,Zhang, Yun, Liu, & Xiong, 2018; Han et al., 2018).To eliminate the impact of ROS, the antioxidant defense system plays an important role(Jiao et al., 2019).SOD is the first line of defense in the antioxidant system, which catalyzes the dismutation of O2-to H2O2and molecular oxygen, and then decomposes into water by CAT.The high level of SOD and CAT activities indicated that the antioxidant system was activated in response to transport stress.The decreased activities of SOD in serum and hepatopancreas on the 7th and 14th day after stress indicated that it might mainly play a role in the early stage after stress.While the activity of CAT in hepatopancreas still increased gradually.The main role of CAT was to remove excess H2O2residue accumulated during stress and make it return to the normal level.A similar phenomenon has been found in largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) (Sun et al., 2020).

The immune defense of crustaceans includingP.clarkiimainly relies on nonspecific immunity.LZM and ACP are directly related to immune function and can be used to reflect immune status (Hong, Yin, Huang,Huang, & Yang, 2020).LZM plays an important role in killing pathogens, and ACP is a major phosphatase that plays a positive role in the immune system as a part of lysosomal enzymes (Mazorra, Rubio &Blasco, 2002).In this study, the activities of ACP and LZM were decreased on the 1st day after transport stress, indicating that transport stress inhibited the immune response ofP.clarkii.The effect of transport stress on the expression ofproPOandctlwas consistent with the results of immune-related enzymes detected.The expression levels of immune-related genesproPOandctlin hepatopancreas also decreased in the early stage of culture after transport stress.Studies have shown that proPO system plays an important role in the innate immune responses through its association with a variety of cellular responses in hemocytes(Qin, Babu, Lin, Dai, & Lin, 2019) and was considered as the most important immune system in crustaceans (Zheng et al., 2019).It was reported that ctl protein could kill bacteria directly and played a critical role in anti-viral infection (Kwankaew, Praparatana, Runsaeng, &Utarabhand, 2018; Liu et al., 2019).

Apoptosis is a programmed cell death and caspase-3 is a death protease that is frequently activated and is closely involved with the dismantling of the cell and the formation of apoptotic bodies (Porter &J¨anicke, 1999).As a key component of the apoptotic pathway, caspase-3 is also indispensable in the immune response (Woo et al., 1998; Wang,Zhi, Wu, & Zhang, 2008).Chen (2019) found thatPCcaspase-3Ccould regulate the expression of antimicrobial peptides inP.clarkii.The activation of caspase-3 induced apoptosis inScylla paramamosainby air exposure (Cheng et al., 2019).The relative expression ofcaspase-3in hepatopancreas ofP.clarkiiwas detected before and after transport stress to reflect the immune and cellular status in this study.The expression ofcaspase-3was inhibited within 3 days after transport stress,which might be related to the immunosuppression caused by transport stress.The increase ofcaspase-3expression in the late stage of the culture after stress may be related to the increase of WSSV concentration.The result was consistent with the increase ofcaspase-3expression in hemolymph ofPenaeus mojimineafter WSSV stimulation (Phongdara,Wanna & Chotigeat, 2006).WSSV is the most harmful and commonly infected virus in shrimp, which causes serious losses to cultured shrimp every year (Chen & He, 2018).WSSV is less harmful to crayfish than shrimp, but it has led to a great impact on the healthy culture industry and economy ofP.clarkii(Zhang, Li, et al., 2020), and the infection of crayfish is ubiquitous in aquaculture.WSSV resistance is related to environmental stress (Yuan et al., 2017).Our results showed that the concentration of WSSV on the 1st day of culture decreased significantly after transport stress, which might be related to the inhibitory effect of WSSV replication by ROS produced by oxidative stress (Thitamadee,Srisala, Taengchaiyaphum, & Sritunyalucksana, 2014).Then, with the removal of ROS by the antioxidant system and the deterioration of water quality caused by the death of a large number of crayfish, the concentration of WSSV increased significantly on the 3rd to 7th day of culture,and the period was also the mortality peak ofP.clarkii.There was no significant difference in the concentration of WSSV of surviving crayfish on the 14th day of culture compared with before transport.In our experiment, the mortality ofP.clarkiiunder transport stress was closely related to the change of concentration of WSSV.

We also detected the same indexes of the dying crayfish cultured on the 5th and 7th day after transport stress, and tissue sections were made to observe the histopathological structure of hepatopancreas, intestines,and gills.The higher levels of cortisol and glucose in serum of dying crayfish indicated that dying crayfish were in a state of oxidative stress,while the expression level ofHSP70in heart was significantly lower than that of vibrant crayfish.Our results showed that the expression ofcaspase-3(the proapoptotic gene) was significantly increased in hepatopancreas of dying crayfish, which might be related to the decreased expression ofHSP70.The antioxidant enzyme activity (SOD, CAT),immune-related enzyme activity (ACP, LZM), immune-related genes(proPO,ctl) expression, and the concentration of WSSV in hepatopancreas were all significantly higher than those of vibrant crayfish.From the results of our histological examination of hepatopancreas, intestines and gills, the hepatopancreas, intestines and gills of dying crayfish were damaged.The severe damage of hepatopancreas and intestines could infer that the oxidative stress response ofP.clarkiiwas induced by transport stress and the culture environment.Antioxidant enzymes played a role in maintaining the elimination of ROS in the body.The WSSV resistance was reduced due to the environmental stress.Then the immune response was activated to suppress the invasion of WSSV.Due to the differences among individuals, the degree of oxidative stress and immune response ofP.clarkiiin the same group at the same period was different, and someP.clarkiiachieved balance again through their own regulation, while some individuals with weaker physique or more severely affected by stress exceed the threshold that could be regulated by themselves (Hong, 2004).The generation and elimination of ROS might be unbalanced, which can damage DNA, proteins and tissue,activate proapoptotic genes, induce cell apoptosis, increase the concentration of WSSV, and ultimately lead to the death (Serafini, Souza,Baldissera, Baldisserotto, & Silva, 2019).Future research should focus on if it could improve the survival rate ofP.clarkiiafter transport from the aspect of WSSV resistance.

5.Conclusion

In summary, compared with exposed-to-air transport, the survival rate of ice-cold transport was higher.The mortality peak period was the 3–9 days after transport stress.The changes ofP.clarkiiphysiological state transported by the two transport methods were similar.Transport stress could trigger immune stress, antioxidant defense, and suppress the immune response.The mortality ofP.clarkiiafter transport stress was related to oxidative stress, unbalanced regulation of ROS, and decreased WSSV resistance, which resulted in the increased concentration of WSSV causing by tissue damage beyond the adjustable threshold range ofP.clarkii.Further studies are necessary to determine whether the survival rate ofP.clarkiiafter transport can be improved by increasing WSSV resistance.

Conflict of insterest

No conflict of interest exits in the submission of this manuscript, and manuscript is approved by all authors for publication.I would like to declare on behalf of my co-authors that the work described was original research that has not been published previously, and not under consideration for publication elsewhere, in whole or in part.All the authors listed have approved the manuscript that is enclosed.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ruixue Shi:Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft,Formal analysis.Siqi Yang:Investigation.Qishuai Wang:Investigation.Long Zhang:Writing – review & editing.Yanhe Li:Investigation,Project administration, Supervision, Resources, Writing – review &editing.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2662020SCPY004) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2020YFD0900304).

Aquaculture and Fisheries2023年5期

Aquaculture and Fisheries2023年5期

- Aquaculture and Fisheries的其它文章

- The effectiveness of light emitting diode (LED) lamps in the offshore purse seine fishery in Vietnam

- Effects of dietary phosphorus level on growth, body composition, liver histology and lipid metabolism of spotted seabass (Lateolabrax maculatus)reared in freshwater

- Immunomolecular response of CD4+, CD8+, TNF-α and IFN-γ in Myxobolus-infected koi (Cyprinus carpio) treated with probiotics

- Expression of gastrin and cholecystokinin B receptor in Lateolabrax maculatus

- The first draft genome assembly and data analysis of the Malaysian mahseer(Tor tambroides)

- The competitiveness of China’s seaweed products in the international market from 2002 to 2017