Unraveling the mechanisms of a giant coronary sinus

Michail Kyrtsopoulos, Apostolos Galatas, Anastasios Kartas?

Cardiology Department, AHEPA University Hospital, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

The coronary sinus (CS) is a tubular venous structure in the left atrioventricular groove that drains around 55% of the deoxygenated coronary arterial blood supply into the right atrium.[1,2]The CS,predominantly a small structure, can be significantly dilated leading to a condition known as giant CS.Giant CS is a clinically important but rare echocardiographic finding, which can be caused by a variety of factors.Herein, we present the unique case of a dilated CS in an 83-year-old male patient that challenges the notion of what“giant” signifies in CS enlargement.

An 83-year-old male patient with a vague history of heart failure presented to our cardiology clinic reporting worsening shortness of breath.His past medical history was significant for the presence of hypertension, dyslipidemia, atrial fibrillation, and hypothyroidism.Physical examination revealed signs of congestion with bilaterally distended jugular veins and a prominent, holosystolic murmur, best heard at the left parasternal base.Electrocardiogram demonstrated atrial fibrillation at approximately 65 beats/min.

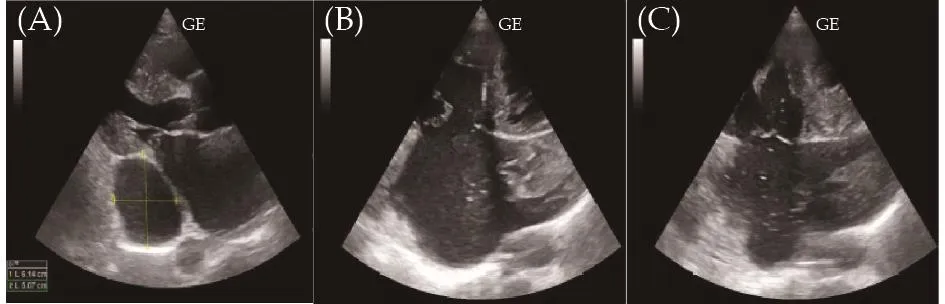

Routine transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) (Figure 1) revealed a massive CS with a craniocaudal diameter of approximately 6 cm.Left ventricular ejection fraction was moderately reduced and there were signs of increased left-sided filling pressures.Further relevant findings were an enlarged right ventricle with impaired longitudinal function, a giant right atrium (area: 60 cm2), a severely regurgitant tricuspid valve, and inferior vena cava dilation.

Figure 1 Transthoracic echocardiography.Echocardiography showing the size of the coronary sinus (A).Contrast echocardiography with use of agitated saline via the right (B) and left antecubital vein (C).

Sequential injection of agitated saline into left and right antecubital veins, showed air bubbles entering the right atrium via the CS.These findings suggest the presence of a persistent left superior vena cava (LSVC) and the absence of a right superior vena cava, respectively.This constellation of congenital defects is referred to as an “isolated LSVC”.

The patient was managed conservatively with diuretics and heart failure treatment.Follow-up echocardiography following decongestion showed slightly reduced CS and inferior vena cava dimensions.

Further diagnostic assessment with CT angiography and cardiovascular magnetic resonance was deemed unnecessary due to the patient’s clinical improvement and the unequivocal findings of the contrast echocardiography.

The normal diameter of the CS is 0.9–1.1 cm, enlargement is usually defined as a diameter greater than 1.1 cm.[3,4]CS enlargement is a rare condition and most commonly an incidental finding.To the best of our knowledge, the craniocaudal diameter of 6 cm presented in our case is the largest in the bibliography.Multiple congenital abnormalities, acquired diseases, or underlying cardiac pathologies can separately or collectively account for such a condition.[4]

An enlarged CS is most commonly an incidental finding in TTE.Although CT angiography and cardiovascular magnetic resonance can reveal the underlying etiology with great accuracy, contrast-enhanced TTE is an important first step.In our case, a simple to perform agitated saline test provided enough information about the presence of a LSVC and the absence of right superior vena cava in a time- and cost-efficient way.

The giant size of the CS in our case would be primarily attributed to the finding of an isolated LSVC.The concomitant presence of left-sided heart failure and severe tricuspid regurgitation, resulting in higher right atrial filling pressures, may have further contributed to the extreme CS dilation.

The presence of a LSVC is the most common anatomic anomaly of the thoracic venous system with an estimated prevalence of 0.57% in the general population.[5]It is commonly associated with other congenital heart diseases and extra-cardiac abnormalities.[6]The LSVC typically drains into the CS due to the embryologic connection between the left common cardinal vein and the left horn of the sinus venosus.[7]However, an isolated LSVC is a much more infrequent anomaly with an estimated prevalence of 0.17%,[8]in which the venous return from the upper half of the body flows into the right atrium via a dilated CS.

The presence of an isolated LSVC is an anatomic anomaly with critical clinical implications, many of which pertain to its tortuous course.Central vein catheterization can be an arduous procedure with possible complications.Similarly, pacemaker lead or pulmonary artery catheter deployment may be impossible owing to the tortuous course alongside the acute angle between the CS ostium and the tricuspid valve.From a cardiothoracic surgeon’s perspective, retrograde cardioplegia may be ineffective in isolated LSVC.Finally, the absence of the right superior vena cava in isolated LSVC is correlated with arrhythmias and conduction abnormalities seemingly due to the abnormal embryological development of the right horn of sinus venosus from which the sinus and the sinoatrial node derive.[9]

In conclusion, we presented the unique case of probably the largest CS ever reported, in an elderly patient with an isolated LSVC, left-sided heart failure, and severe tricuspid regurgitation.When confronted with an exceedingly large CS, the use of bilateral agitated-saline injections helps uncover an isolated LSVC, which is a very rare condition with high clinical significance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

All authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2023年6期

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2023年6期

- Journal of Geriatric Cardiology的其它文章

- Status of cardiovascular disease in China

- Iatrogenic pneumopericardium after therapeutic pericardiocentesis for pericardial effusion: a case report

- Target versus sub-target dose of renin–angiotensin system inhibitors on survival in elderly patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Outcomes of catheter-directed thrombolysis versus systemic thrombolysis in the treatment of pulmonary embolism: a metaanalysis

- Nocturnal hypertension and riser pattern are associated with heart failure rehospitalization in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- Down-regulation of the Smad signaling by circZBTB46 via the Smad2-PDLIM5 axis to inhibit type I collagen expression