Target versus sub-target dose of renin–angiotensin system inhibitors on survival in elderly patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Long-Kun SUN, Jing KONG, Xiao-Wei YANG, Jing WANG, Peng-Fei ZHANG?

The Key Laboratory of Cardiovascular Remodeling and Function Research, Chinese Ministry of Education, Chinese National Health Commission and Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, The State and Shandong Province Joint Key Laboratory of Translational Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Cardiology, Qilu Hospital, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, Jinan, China

ABSTRACT BACKGROUND The efficiency of the target versus sub-target dose of renin–angiotensin system inhibitors (RASIs) in elderly patients with heart failure (HF) with reduced ejection fraction (HErEF) remains unclear.METHODS PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were searched from database inception through March 2022 for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies considering the effect of the target versus sub-target dose of RASIs on survival in elderly patients (≥ 60 years) with HErEF.The primary outcome was all-cause mortality.The secondary outcomes were cardiac mortality, HF hospitalization, and the composite endpoint of mortality or HF hospitalization.A meta-analysis was conducted to generate combined hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI.RESULTS Seven studies (two RCTs and five observational studies) enrolling 16,634 patients were included.A pooled analysis suggested that the target versus sub-target dose of RASIs led to lower rates of all-cause mortality (HR = 0.92, 95% CI: 0.87–0.98, I2 =21%) and cardiac mortality (HR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.85–1.00, I2 = 15%) but not reduced rates of HF hospitalization (HR = 0.94, 95% CI:0.88–1.01, I2 = 0) and the composite endpoint (HR = 1.03, 95% CI: 0.91–1.15, I2 = 51%).However, the target dose of RASIs was associated with a similar primary outcome (HR = 0.85, 95% CI: 0.64–1.14, I2 = 0) in a subgroup of very elderly patients > 75 years of age.CONCLUSIONS Our analysis suggests that the target dose of RASIs has a better survival benefit in elderly patients with HFrEF compared to the sub-target dose of RASIs.However, the sub-target dose of RASIs is associated with a similar mortality rate in very elderly patients > 75 years of age.Future high-quality and adequately powered RCTs are warranted.

Heart failure (HF) with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) is a chronic condition and a major cause of mortality and morbidity,[1]predominant in elderly individuals > 65 years of age.[2]The prevalence of HF increases dramatically with age,from 2% in the general population to > 10% among those aged ≥ 75 years.[3]Although renin–angiotensin system inhibitors (RASIs) or angiotensin–receptor neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs) have been shown to reduce mortality and morbidity rates in patients with HFrEF,[4–8]few studies included patients > 60 years of age, let alone those > 75 years of age.Based on current guidelines, these medications should be commenced at a low dose and up-titrated to the guideline-recommended target dose (GRTD) or maximal tolerable dose.[9,10]However, two aspects have drawn keen consideration.On the one hand, compared to a low dose (< 50% GRTD), a high dose (> 50% GRTD) of RASIs/ARNIs significantly improves the mortality of HFrEF patients.[11–14]However, in the real world, only 1/3 of HFrEF patients can achieve and maintain the GRTDdue to adverse effects.[15]On the other hand, the guidelines do not differentiate therapy strategies according to age group.[2]The efficacy of treating patients with HFrEF with the GRTD versus the sub-target dose (50%–99%GRTD) of RASIs/ARNIs remains unclear.[16]

Therefore, we performed this meta-analysis to evaluate the efficiency of the target versus sub-target dose of RASIs/ARNIs on survival in patients > 60 years of age with HFrEF.

METHODS

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology reporting guidelines.[17,18]The study protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews under the identification number CRD42020160593.

Literature Search

PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were searched up to March 2022 to identify eligible clinical trials for inclusion in our analysis.The keywords of interest included “heart failure with reduced ejection fraction”, “HFrEF”, “angiotensinconverting enzyme inhibitors”, “ACEI”, “angiotensin receptor blockers”, “ARB”, “angiotensin–receptor neprilysin inhibitors”, “ARNI”, “target dose”, “sub-target dose”, “optimal dose”, and so on.We reviewed full-text articles designated initially for inclusion and manually checked the references of the retrieved articles and previous reviews to identify additional eligible studies.

Selection Criteria

Studies satisfying certain PICO (the Population, Intervention, Comparator, and Outcome) criteria were included.With regard to study population, we considered those studies including elderly patients (≥ 60 years) with HFrEF.Appropriate study designs included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies(prospective or retrospective cohort studies), and appropriate interventions included the target and sub-target doses of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers/ARNIs.For our purposes,the target dose was defined as a dose greater than or equal to the GRTD, while a sub-target dose was defined as that equal to 50%–99% of the GRTD.[9]Outcomes of interest included all-cause mortality, cardiac mortality, HF hospitalization, and the composite endpoint of mortality or HF hospitalization.Finally, studies comparing outcomes of the target and sub-target doses were considered.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

A manual search was conducted among all the identified original articles by two independent investigators.For studies comparing > 2 arm doses, we classified those doses greater than or equal to the GRTD as “target doses” and those that were 50%–99% of the GRTD as“sub-target doses”.We extracted crude outcome data from full-text reports into a standardized database.The extracted data included the study first author, setting, publication year, and design as well as the duration of follow-up, the sample size, the drugs being studied and their dosage, baseline patient demographics, and outcomes.The primary outcome was all-cause mortality, and secondary outcomes included cardiac mortality, HF hospitalization,and the composite endpoint of mortality or HF hospitalization.The Cochrane’s risk of bias tool was adopted to assess the risk of bias for each RCT.[19]Observational studies were evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale.[20]

Statistical Analysis

We performed all statistical analyses using the Review Manager 5.30 software (Cochrane Collaboration,London, UK) and Stata 16.0 (Stata Corp, College Station,TX, USA) with the target dose set as the experimental intervention and the sub-target dose set as the control intervention, respectively.A meta-analysis of the study results was completed using pooled hazard ratio (HR)and associated 95% CI.The HR with 95% CI was extracted from articles.For those studies in which HR and CI were not available, adjusted relative risk (RR) values were considered equivalent to adjusted HR.Besides, we used the method proposed by Deeks,et al.[21]to derive estimates from survival curves.If results of both univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were reported,we chose the multivariate models for a more accurate estimate of the effects.P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.Heterogeneity was evaluated using the Q statistic and quantified with the?2statistic.A finding of?2> 50% indicated significant heterogeneity between studies.We performed our analysis using a fixedeffects model initially; however, if heterogeneity was observed, the analysis was repeated using a random-effects model.Subgroup analyses were performed basedon variables, including whether patients were aged > 75 years and the study design.Meta-regression was then performed for incidence rates against variables of interest.Publication bias was assessed by funnel plot analysis.

RESULTS

Study Selection and Patient Population

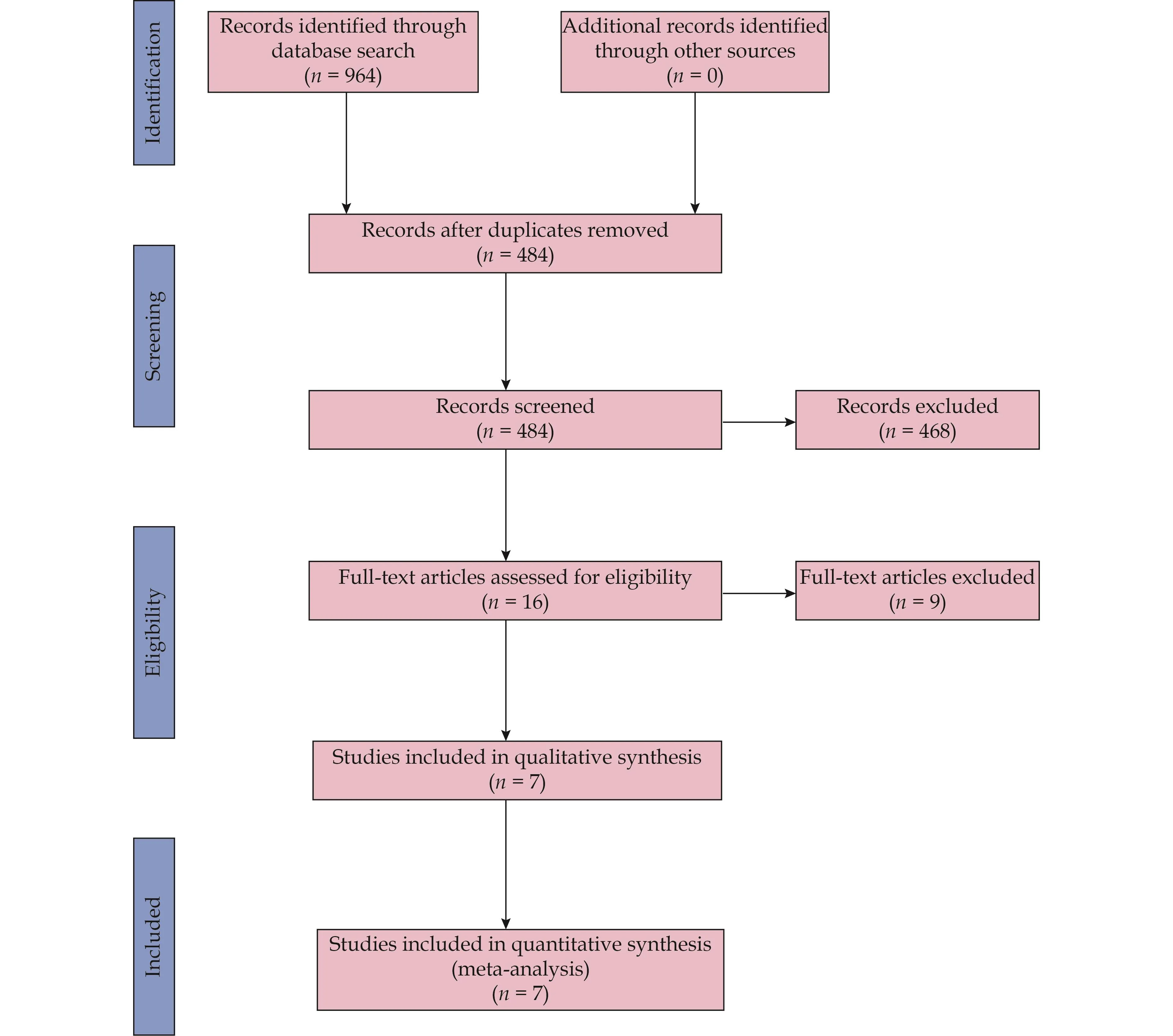

We identified 16 relevant articles after reviewing the titles or abstracts of 484 potentially relevant articles.All 16 articles of 7 studies[16,22–27]satisfying our eligibility criteria were finally included in this meta-analysis.The literature search and screening process are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Flow diagram of the literature search and study selection process.

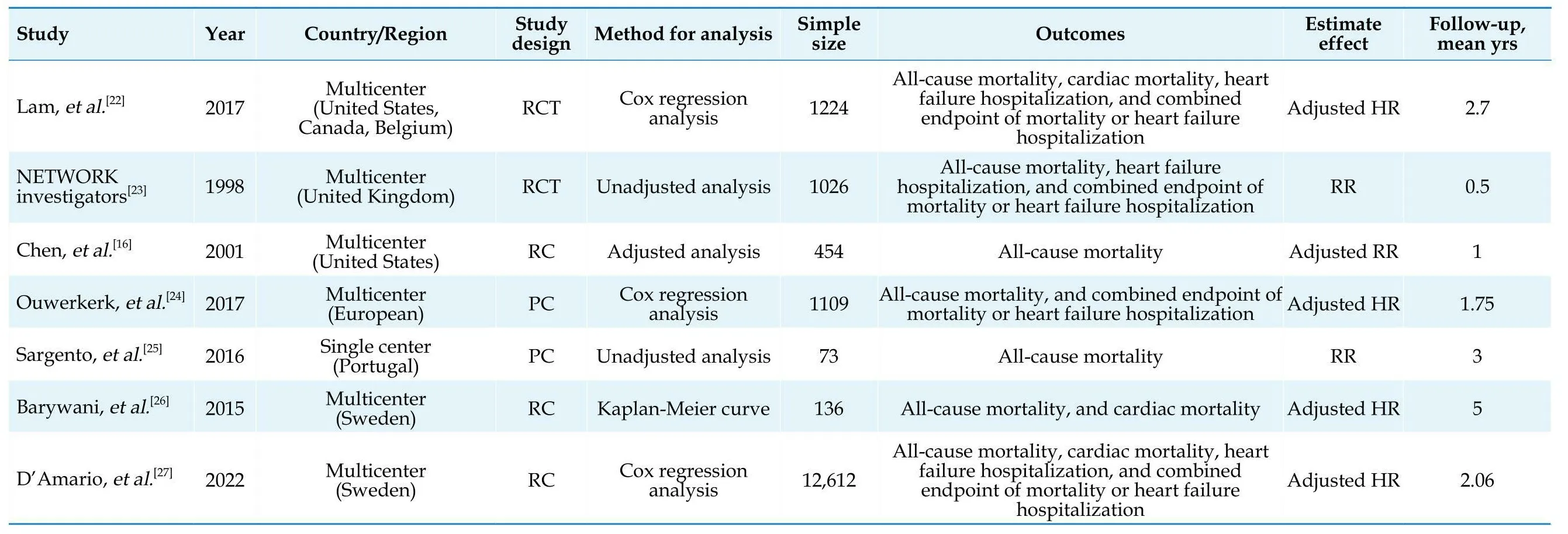

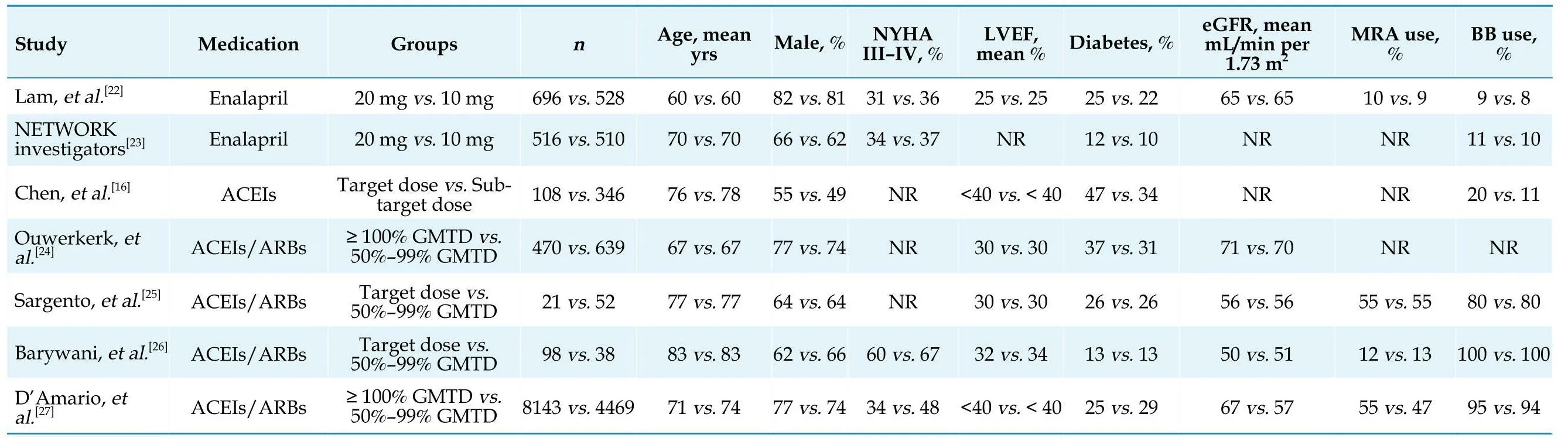

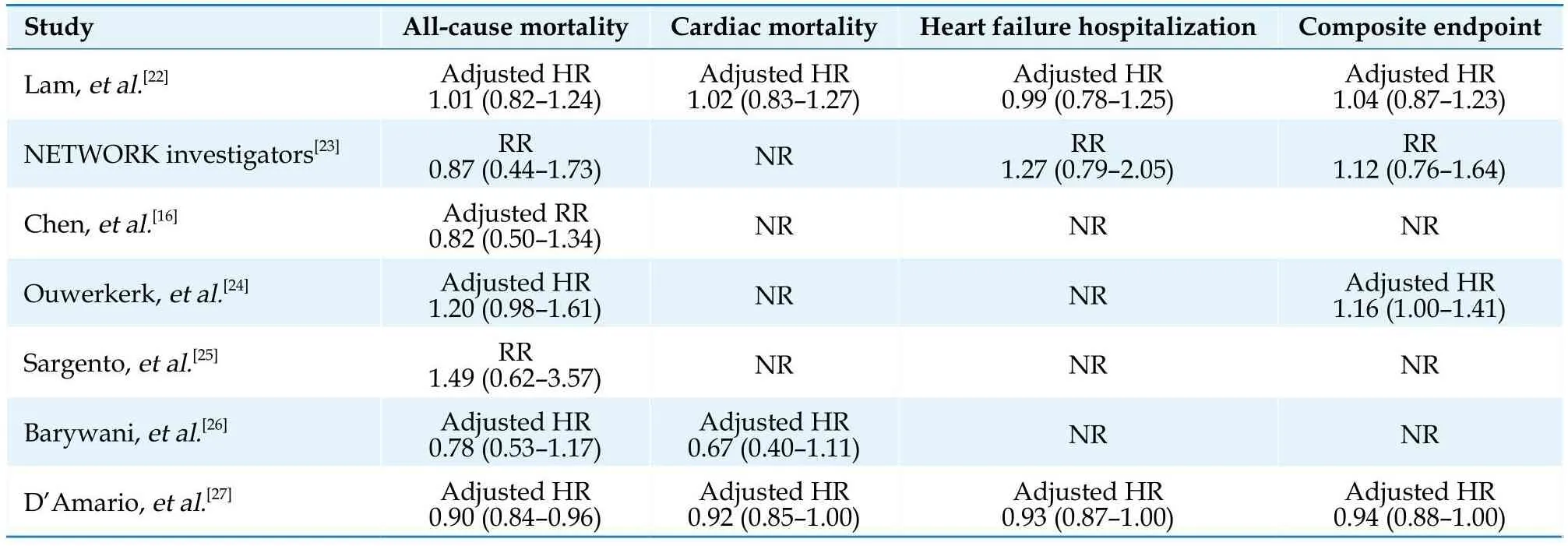

The main characteristics of the included studies and populations are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2, and the outcomes data of each included study are shown in Table 3.The seven studies of interest included two RCTs[22,23]and five observational studies (three retrospective studies[16,26,27]and two prospective studies[24,25]) containing a total of 16,634 patients (10,052 patients in the target dose group and 6582 patients in the sub-target dose group).The seven studies[16,22–27]were conducted in the United States, Canada or Europe and published from 1998 to 2022.Across the included studies, the reported mean age ranged from 60–83 years, left ventricular ejection fraction values ranged from 25%–40%, and the follow-up period ranged from 0.5–5 years in length, respectively.Four of the five observational studies[16,24–27]conducted a multivariate analysis to adjust for confounding variables.

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies.

Table 2 Baselinepatients characteristics of included studies.

Table 3 Clinical outcomes of included studies.

Quality Assessment

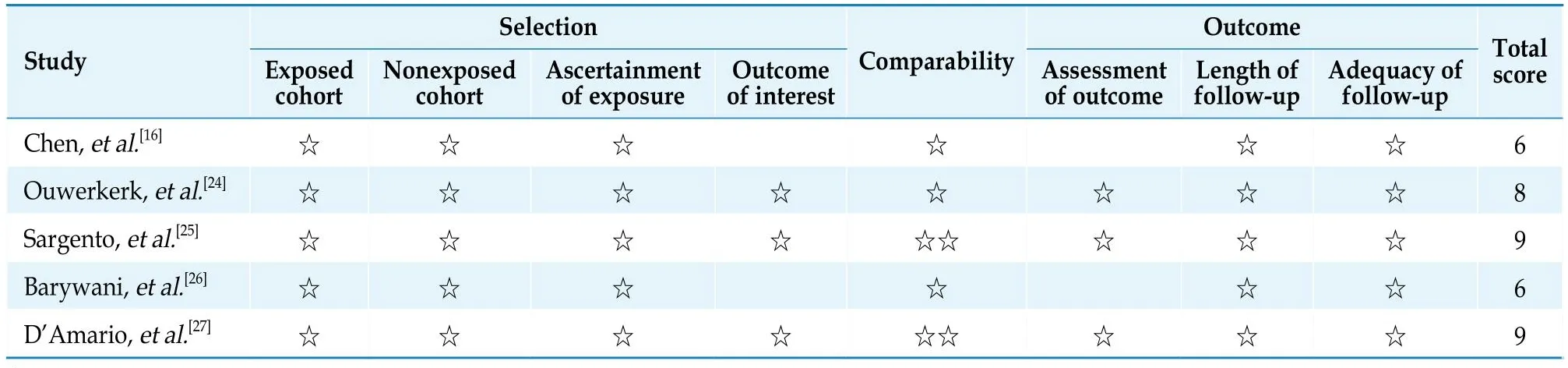

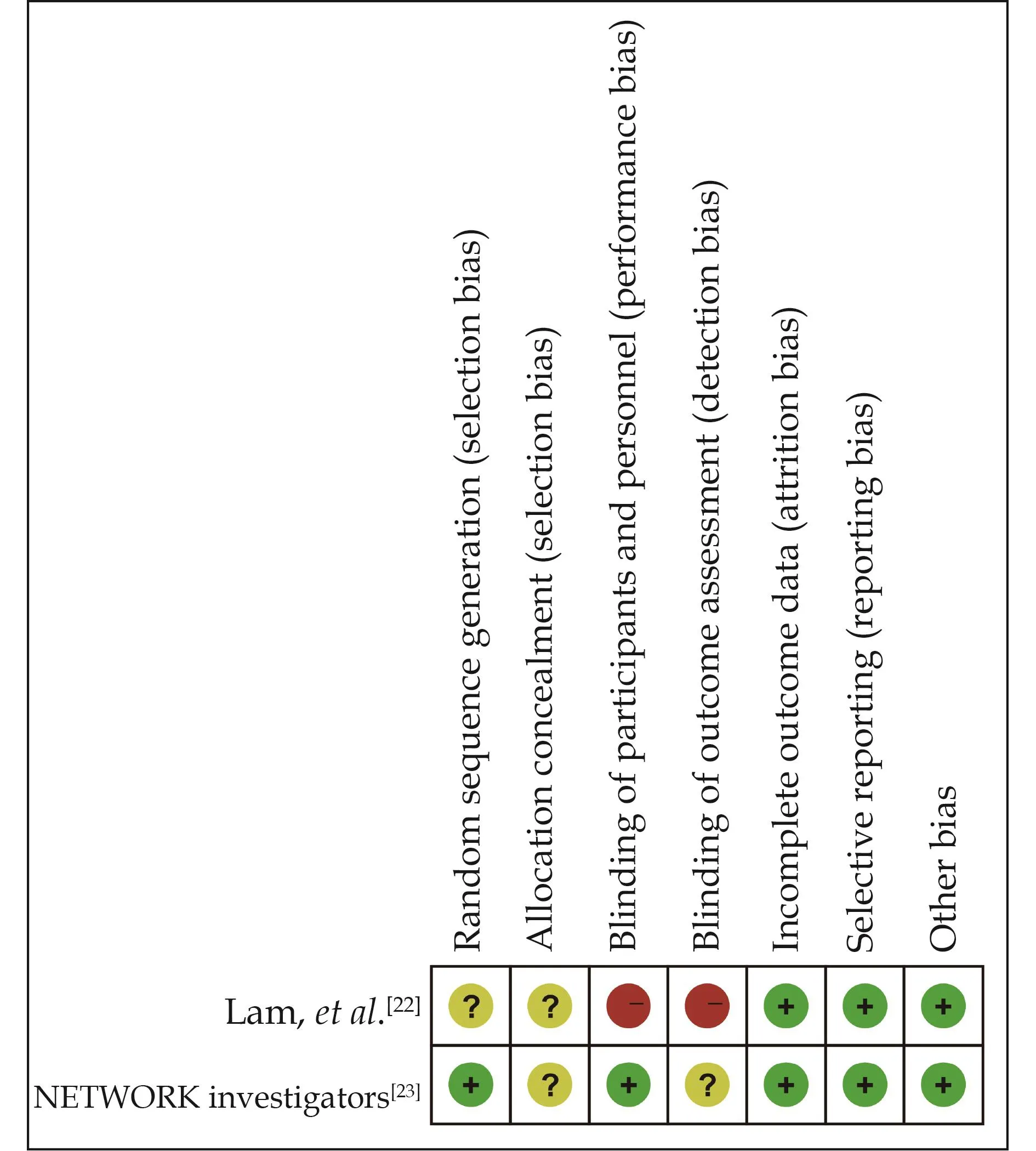

A risk-of-bias assessment on the included studies is presented in Figure 2 and Table 4.One RCT[22]showed a medium risk of bias, the other one was rated as low risk of bias.[23]Meanwhile, the five observational studies[16,24–27]showed a low risk of bias with a total score of > 5 points based on the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale.

Table 4 Risk of bias assessment of included observational studies.

Figure 2 Risk-of-bias assessment of the included randomized controlled trials.

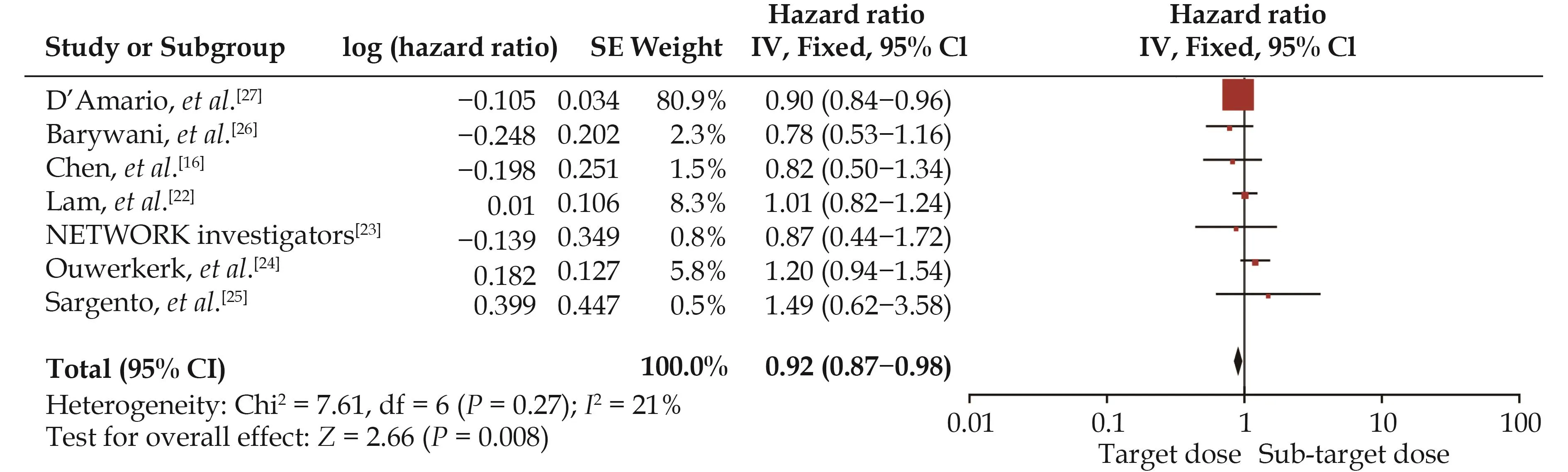

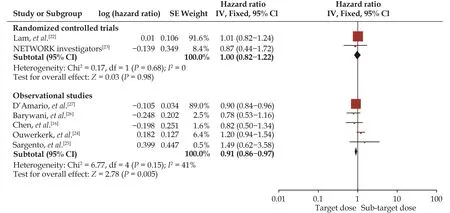

Primary Outcome

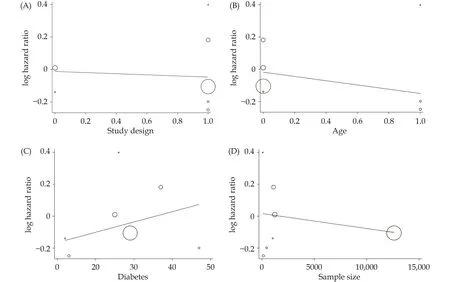

Seven studies[16,22–27]were included in the analysis of the effect of RASIs dose on all-cause mortality (Figure 3).The target dose led to a better survival benefit in patients aged ≥ 60 years with HFrEF compared to the sub-target dose (HR = 0.92, 95% CI: 0.87–0.98,I2= 21%).No significant heterogeneity was found across the studies (I2=21%,P= 0.27).Note that the observed survival benefit may largely rely on data from the subgroup of observational studies (HR = 0.91, 95% CI: 0.86–0.97,I2= 41%) (Figure 4).Meta-regression of HR across studies revealed no significant association between RASIs doses and the study design, age, diabetes, or sample size (Figure 5).

Figure 3 Effect of the target versus sub-target dose of renin–angiotensin system inhibitors on all-cause mortality.

Figure 4 Effect of the target versus sub-target dose of renin–angiotensin system inhibitors on all-cause mortality in randomized controlled trials and observational study subgroups.

Figure 5 Meta-regression of the effect of study design (A), age (B), diabetes (C), or sample size (D) on all-cause mortality.

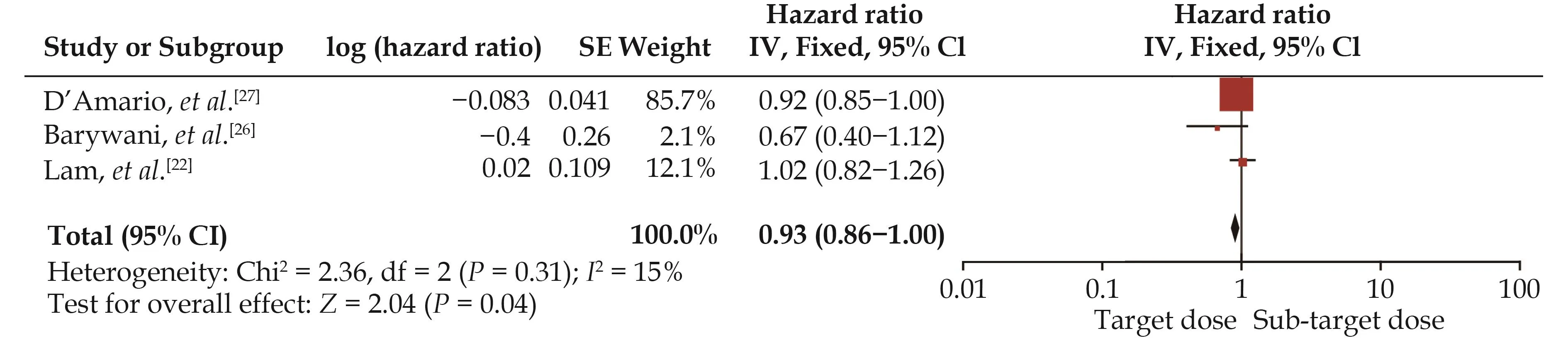

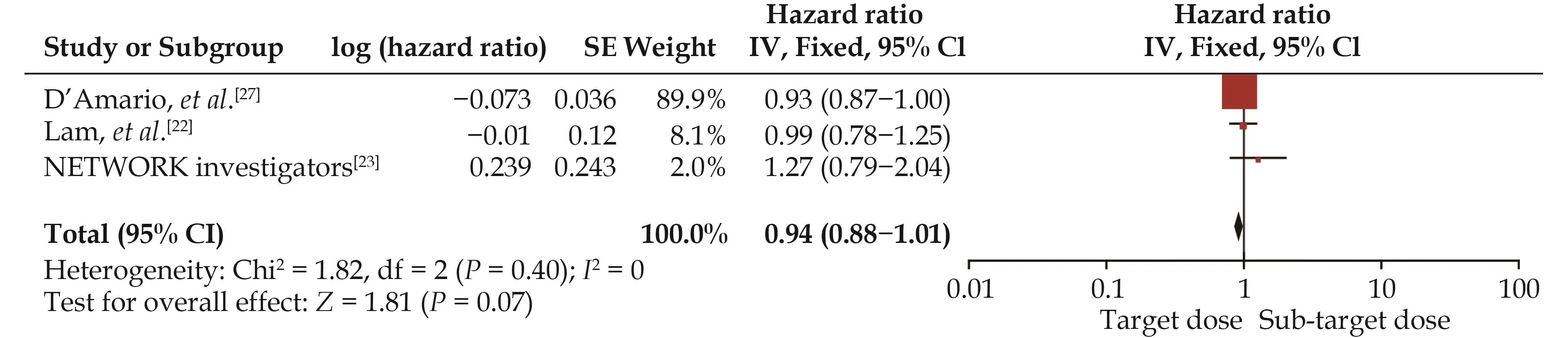

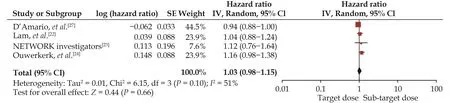

Secondary Outcomes

A pooled analysis suggested that the target dose of RASIs led to a lower rate of cardiac mortality (HR = 0.93,95% CI: 0.85–1.00,I2= 15%) (Figure 6) but not of HF hospitalization (HR = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.88–1.01,I2= 0) (Figure 7) or the composite endpoint (HR = 1.03, 95% CI:0.91–1.15,I2= 51%) (Figure 8).

Figure 6 Effect of the target versus sub-target dose of renin–angiotensin system inhibitors on cardiac mortality.

Figure 7 Effect of the target versus sub-target dose of renin–angiotensin system inhibitors on heart failure hospitalization.

Figure 8 Effect of the target versus sub-target dose of renin–angiotensin system inhibitors on the composite endpoint of mortality or heart failure hospitalization.

Subgroup Analysis of HFrEF Patients Aged > 75 Years

We further conducted a subgroup analysis to interrogate the dose-related effect of RASIs in patients > 75 years of age.The target dose of RASIs was associated with a similar outcome of all-cause mortality (HR = 0.85, 95%CI: 0.64–1.14,I2= 0) in this very elderly population (Figure 9).

Figure 9 Effect of the target versus sub-target dose of renin–angiotensin system inhibitors on all-cause mortality in patients aged> 75 years.

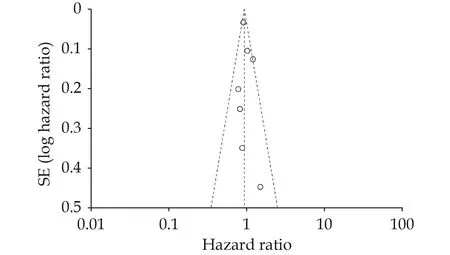

Publication Bias

Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots.We found that the funnel plots for all-cause mortality were symmetric, indicating no evidence of publication bias(Figure 10).

Figure 10 Funnel plot representing publication bias for all-cause mortality.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of the present systematic review and meta-analysis was that in elderly patients with HFrEF, the target (versus sub-target) dose of RASIs led to lower rates of all-cause mortality and cardiac mortality, which may reinforce the recommendations of the guideline’s recommendation to up-titrate the RASI dose in elderly patients.[9]However, for HFrEF patients older than 75 years, our results did not support the superiority of the target dose of RASIs.

Target dose of RASIs is usually hard to achieve in elderly patients with HFrEF, due to frailty and complicated comorbidity.Evidences on this special population are debatable.Ouwerkerk,et al.[28]found that the sub-target dose of RASIs was not inferior to the target dose on allcause mortality rate in patients with HFrEF; however,their study’s relatively small sample size (n= 369) might hamper the statistical power.

Khan,et al.[13]considered 9171 patients from six RCTs and concluded that high-dose (versus low-dose) RASIs decreased the all-cause mortality rate modestly (RR =0.94, 95% CI: 0.89–1.00,P= 0.05,I2= 0).It is worth noting that the definition of the low dose in most of the six RCTs was much lower than half dose of the GRTD mentioned in our study.Turgeon,et al.[29]included ten RCTs and reached the opposite conclusion.However, in this study,the results were quantitatively nearly identical (95% CI:0.89–1.02vs.95% CI: 0.89–1.00), so the findings might be overrated.[30]In these two meta-analyses, the dose definition of “high” and “l(fā)ow” was vague and arbitrary to some extent.In our study, we selected the target dose and sub-target dose with clear dose ranges.In addition,the RR was calculated in the meta-analyses.It emphasizes the event counts and the number of patients in each group, but might neglect the fact that the events accumulate over time.[31]We performed HR analysis instead,which is more appropriate when analyzing time-to-event outcomes.Nevertheless, the beneficial tendency of higher dose of RASI on mortality was consistent across studies.

The dosage of RASIs is particularly important in HFr-EF patients > 75 years of age, who are not a negligible population in clinical practice despite their under-representation in large RCTs.[32]Some RCTs without a specific ageexclusion criterion failed to recruit sufficient numbers of these very elderly patients.[2,33]Only three observational studies[16,25,26]enrolled in our study met the age criteria, and the results showed the sub-target dose was associatedwith a similar risk of all-cause mortality in this very elderly population.Since the benefit of RASI was evidenced in the Euro Heart Failure Survey II, the Swedish Heart Failure Registry trial, and other studies, it can be inferred that the optimal dose should be individualized in octogenarian patients with HFrEF.[3,34,35]

LIMITATIONS

Several potential limitations should be taken into consideration.Firstly, only two RCTs and five observational studies were included in this analysis.Observational studies are inclined to have selection bias and confound-ing by indication.However, four of the five enrolled observational studies were designed using adjusted analysis to reduce the effects of confounders.Secondly, for patients aged > 75 years, we only performed a subgroup analysis due to the paucity of data from relative RCTs concerning these patients.Last but not least, although ARNIs have a similar pharmaceutical effect as RASIs,only a single study compared the outcome differences between target and sub-target doses of ARNIs in the elderly population.[36]Thus, we did not consider ARNIs in our meta-analysis.It should point out the study comparing the efficiency of target and sub-target doses of RASIs and ARNI by D’Amario,et al.[27]was included,because most patients (92.1%) in this study took RASIs.

CONCLUSIONS

Our analysis suggests that the target dose of RASIs leads to a better survival benefit in elderly patients with HFrEF compared to the sub-target dose of RASIs.However, the sub-target dose of RASIs is associated with a similar mortality rate in very elderly patients > 75 years of age.Future high-quality and adequately powered RCTs are warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Key R&D Program of Shandong Province (No.2020ZLYS05).All authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2023年6期

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2023年6期

- Journal of Geriatric Cardiology的其它文章

- Status of cardiovascular disease in China

- Unraveling the mechanisms of a giant coronary sinus

- Iatrogenic pneumopericardium after therapeutic pericardiocentesis for pericardial effusion: a case report

- Outcomes of catheter-directed thrombolysis versus systemic thrombolysis in the treatment of pulmonary embolism: a metaanalysis

- Nocturnal hypertension and riser pattern are associated with heart failure rehospitalization in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- Down-regulation of the Smad signaling by circZBTB46 via the Smad2-PDLIM5 axis to inhibit type I collagen expression