Student self-assessment of strengths and needed improvements during a family medicine clerkship

William Huang, Kenneth Barning, Larissa Grigoryan

Student self-assessment of strengths and needed improvements during a family medicine clerkship

William Huang, Kenneth Barning, Larissa Grigoryan

Objective:There are few reports on how students self-assess their performance on a family medicine clerkship. We studied what students perceived as their strengths and areas of needed improvement at the mid-point in our family medicine clerkship.

Methods:We introduced a form for family medicine clerkship students to self-assess their strengths and areas of needed improvements using the clerkship objectives as a standard. We calculated the frequency in which each clerkship objective was reported as a strength or an area of needed improvement. For students’ open-ended comments, two reviewers independently organized students’ comments into themes, then negotiated any initial differences into a set of themes that incorporated both the reviewers’ findings. We performed χ2tests to determine any significant differences in the frequency of responses between male and female students.

Results:During the study period (July 2012 to June 2014), 372 students submitted completed self-assessment forms. The most frequently reported strengths were professional objectives(48.9%) and interpersonal communication objectives (43.0%) The most frequently reported areas of needed improvement were the ability to explain key characteristics of commonly used medications (29.3%) and the ability to develop a management plan (28.5%). There were no significant differences in the frequency of responses between male and female students.

Conclusion:We now have a better understanding of students’ perceived strengths and areas of needed improvement in our family medicine clerkship. We have shared this information with our community faculty preceptors so that they will be better prepared to work with our students.Family medicine clerkship preceptors at other institutions may also find these results useful.

Education; medical; undergraduate; clinical clerkship; student self-assessment

Introduction

There is an abundance of literature regarding medical student self-assessment. Many studies have investigated the accuracy of student self-assessment and explored the factors that contribute to accuracy [1–4]. More recent studies have explored student self-assessment in emergency medicine clerkships. Bernard and colleagues [5] reviewed self-assessment narratives of fourth-year students on an emergency medicine clerkship and noted that students commonly expressed that historytaking, physical examination, and patient care were strengths, and that developing a plan of care, differential diagnosis, presentation skills, and knowledge base were areasof needed improvement. Similarly, Avegno and colleagues [6]conducted pre- and post-surveys of students on an emergency medicine clerkship (either 2 or 4 weeks) and noted that students gained confidence in initial patient assessment, diagnosis, management plans, and basic procedure skills during the clerkship.

There are some reports involving student self-assessments on a family medicine clerkship; however, the reports are out of-date. One study reviewed student self-assessments on a family medicine clerkship and noted that students were more comfortable in diagnosing many common diseases by the end of the clerkship compared with the beginning [7]. Schwiebert and Davis [8] reported that student confidence in a number of cognitive and procedural skills improved by the end of their family medicine clerkship compared with the beginning.Alnasir and Grant [9] asked family medicine clerkship students to assess themselves at 2, 4, and 6 weeks and reported that the end-of-clerkship self-assessments correlated with the evaluations submitted by the preceptor and an independent observer of the student conducting a patient encounter [9];however, there is still much to learn about student self-assessment during a family medicine clerkship. As these reports primarily focus on student self-assessments at the end of the clerkship, we were interested to learn how students assessed themselves at the mid-point of the clerkship when there was still time to improve performance. This paper reports our results after introducing a student self-assessment form at the mid-point of our family medicine clerkship. Although we initiated this form to enable students to self-assess their performance, we also desired to learn the following:

1. What do students perceive as their strengths at the midpoint of a family medicine clerkship?

2. What do students perceive as their needed improvement at the mid-point of a family medicine clerkship?

Methods

The Institutional Review Board of Baylor College of Medicine and affiliated Hospitals approved this educational research study.

The medical school curriculum at Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) is a 4-year curriculum; however, unlike most schools, BCM students only spend the first 1.5 years in the preclinical curriculum. The remaining 2.5 years is devoted to the clinical curriculum.

The Family and Community Medicine clerkship at Baylor College of Medicine is a required 4-week clerkship for clinical students. Most students take the clerkship during their third year of medical school, but a few students take the Family and Community Medicine clerkship during the second half of the second year at the start of clinical rotations. Similar to other family medicine clerkships, students spend the majority of clerkship time in the office of a community-based family physician preceptor participating in clinical ambulatory care.

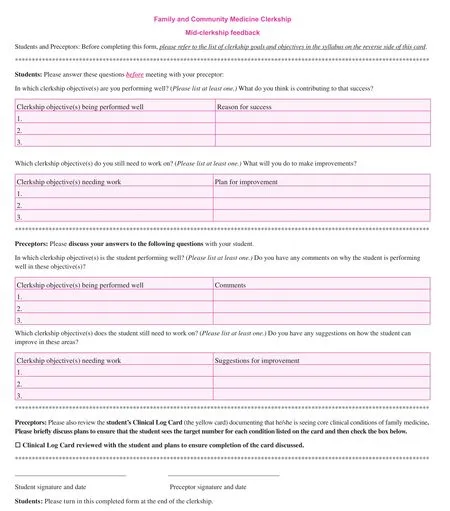

As part of our effort to improve the mid-clerkship feedback process and to answer questions of interest, we introduced a survey form in July 2012 for students to document a self-assessment of their performance at the mid-point of the clerkship and for preceptors to record mid-clerkship feedback that is given to students (Fig. 1). In using the form, we encouraged students and preceptors to use our clerkship objectives(Fig. 2) as the basis for reporting strengths and areas of needed improvement. The purpose of this form was for students to reflect on their performance at that point of the clerkship,receive feedback from their faculty preceptor, and plan how to work on areas of needed improvement during the remaining weeks of the clerkship. Submission of this student self-assessment and preceptor feedback was a required component of the clerkship, but was not graded. This paper will focus on our analysis of student self-assessments, but will not address preceptor feedback comments.

We calculated the frequency in which each clerkship objective was listed as a strength or an area of needed improvement. Students also wrote responses on the form which did not match a clerkship objective. For those open-ended responses,two faculty reviewers (WH and KB) independently organized the responses into themes. The two reviewers compared their findings, prioritized common themes, and negotiated any initial differences into a set of themes that incorporated both reviewers’ findings.

We also performed χ2tests to determine if there were any significant differences in the frequency of responses between male and female students. A p value <0.05 were considered statistically significant. SPSS (version 22; SPSS, Inc., Chicago,IL, USA) was used to perform the statistical analyses.

Fig. 1. Front side of student self-assessment and preceptor feedback form used at mid-clerkship.

Results

During the study period (July 2012 to June 2014), 372 students (213 males and 159 females) completed the Family and Community Medicine clerkship and all submitted a form documenting self-assessment at the mid-point of the clerkship.

Students most frequently reported professional objectives(48.9%) and interpersonal communication objectives (43.0%)as areas of strengths. The ability to conduct a focused history and physical examination (29.3%) and explain information on the diagnosis and management of ambulatory conditions(21.0%) were next in frequency as reported strengths.

Explaining information about ambulatory medications(29.3%) was the most frequent reported area of needed improvement. Many students also submitted open-ended responses,noting that they desired to improve their ability to develop a management plan (28.5%). Using an evidence-based approach to answering questions (19.9%) was next in frequency of areas of needed improvement. Several students (17.7%) reported systems-based practice objectives and a variety of other systemsbased practice issues, such as learning about health insurance issues, as needing improvement. Finally, the ability to conduct a focused history and physical examination (17.5%) and the ability to present the case verbally and in writing (16.4%) were also frequently mentioned as areas of needed improvement.

There were no significant differences in the frequency of responses between male and female students for any of the items.

Table 1 lists a summary of all results.

Discussion

We now have a better understanding of what students perceive as their strengths and areas of needed improvement at the midpoint of our family medicine clerkship.

Some findings of our study were expected. Students listed professionalism and interpersonal communication objectives as strengths. These perceived strengths may be because of a required preclinical course called “Patient, Physician, and Society,” which is taken during the first 1.5 years in medical school, during which our students learn the communications skills needed to take a patient history and the professional behavior that is expected of physicians. The finding that interpersonal communication objectives were a reported strength is similar to results where emergency medicine clerkship students self-assessed their communications and rapport-building skills as strengths at the mid-point of an emergency medicine clerkship [5]. The finding that professional objectives were a reported strength is supported by another study which noted that students rated their achievement of professional competencies highly in their first year of medical school, and those ratings remained stable throughout the remaining years of medical school [11].

Another expected finding was that students reported systems-based practice objectives as areas of needed improvement. These issues are not covered in detail in our preclinical curriculum, and students understandably felt the need to learn more about them during the clerkship.

As expected, many students felt a need to improve their ability to develop a management plan. This need likely occurs for students in all core clerkships. In accordance with our clerkship objectives, our students mentioned the need to improve their skills in developing a management plan in general or specific types of visits (prevention and chronic illness)more frequently. In contrast, students in an emergency medicine clerkship felt that their ability to choose diagnostic tests,propose a therapeutic plan, and determine patient disposition or follow-up were specific areas of needed improvement in developing management plans for the clerkship [5].

Other study findings were encouraging. More students listed the ability to do a focused history and physical examination as a strength rather than as an area of needed improvement.Learning to do a focused history and physical examination is a new skill learned during our clerkship and a focus of our Task-oriented Processes in Care (TOPIC) seminar curriculum given to students at the beginning of the clerkship [12, 13].Although we already know that students demonstrate the ability to conduct focused history and physical examinations at the end of the clerkship on a Clinical Performance Examination with standardized patients, it is gratifying to see that many students rated their ability to do a focused history and physical examination as a strength at the mid-point in the clerkship.Similarly, it has been reported that students felt that taking focused histories and conducting focused physical examinations are strengths of an emergency medicine clerkship [5].

It was unexpected that the objective, “explain(s) the mechanisms of action, indications, advantages, side-effects, andcontraindications of medications used in the management of common ambulatory conditions,” was considered an area of needed improvement. Even though clinical pharmacology is a core subject in the preclinical curriculum, our results indicate that many students still felt that this area needed more emphasis during the Family and Community Medicine clerkship.As students in an emergency medicine clerkship reported the need to improve their knowledge base (most frequently, medical illnesses and medications) [5], our findings indicated that our clerkship students wanted to improve facility with common medications that are a specific part of the knowledge base in family medicine.

Regarding the objectives cited by students as areas of needed improvement, students demonstrated achievement of many of these objectives by the end of the clerkship. Although many students felt their knowledge of commonly used medications and their ability to use evidence-based medicine to answer clinical questions needed improvement at the mid-point of the clerkship,students generally did well in demonstrating both of these items on a knowledge-based Clinical Case Examination at the end of the clerkship. Similarly, many students felt their knowledge of systems-based practice issues needed improvement at the middle of the clerkship, but all submitted a paper demonstrating their understanding of the patient-entered medical home, [14] a concept that is evolving in the current US health care system, and its application to their future career at the end of the clerkship.

One limitation of our study was that the study was conducted in a family medicine clerkship at one medical school and the results may not be generalizable to other clerkships or institutions. Second, although this self-assessment exercise was not a graded assignment for our clerkship, it was nevertheless required, and that may have influenced how students completed the self-assessment form. Finally, another limitation resulted from the fact that some students wrote about strengths or areas of needed improvement that were not clerkship objectives. Although we made an effort to review these responses and organize the objectives into themes, we may not have completely understood the full meaning of students’ open-ended responses.

Despite these limitations, our findings give insight to what students perceive as their strengths and areas of needed improvement at the mid-point of our family medicine clerkship. We have shared this information with our clerkship preceptors so that they will better understand student perspectives and respond to student needs. Our findings may also be useful for family medicine clerkship preceptors at other institutions.

Further study to investigate whether or not our students actually worked on the reported areas of needed improvement would give additional understanding on how their self-assessment contributed to their development as competent physicians. In addition, a study performed at other institutions may give further insight to student perspectives of their strengths and areas of needed improvement when in a family medicine clerkship.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Elvira Ruiz, coordinator of the Family and Community Medicine clerkship, for her assistance in collecting and transferring students’ self-assessment statements to an electronic spreadsheet.

conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-pro fit sectors.

1. Coutts L, Rogers J. Predictors of student self-assessment accuracy during a clinical performance exam: comparisons between over-estimators and under-estimators of SP-evaluated performance. Acad Med 1999;74(10 Suppl):S128–30.

2. Woolliscroft JO, Ten Haken J, Smith J, Calhoun JG. Medical students’ clinical self-assessments: comparisons with external measures of performance and the students’ self-assessments of overall performance and effort. Acad Med 1993;68(4):285–94.

3. Fitzgerald JT, Gruppen LD, White CB. The influence of task formats on the accuracy of medical students’ self-assessments. Acad Med 2000;75(7):737–41.

4. Blanch-Hartigan D. Medical students’ self-assessment of performance: results from three meta-analyses. Patient Educ Couns 2011;84(1):3–9.

5. Bernard AW, Balodis A, Kman NE, Caterino JM, Khandelwal S.Medical student self-assessment narratives: perceived educational needs during fourth-year emergency medicine clerkship.Teach Learn Med 2013;25(1):24–30.

6. Avegno JL, Murphy-Lavoie H, Lofaso DP, Moreno-Walton L. Medical students’ perceptions of an emergency medicine clerkship: an analysis of self-assessment surveys. Int J Emerg Med 2012;5(1):25.7. Ware BR. A two-year self-assessment evaluation by students in a family medicine clerkship. Acad Med 1989;64(5):279–80.

8. Schwiebert LP, Davis A. Impact of a required third-year family medicine clerkship on student self-assessment of cognitive and procedural skills. Teach Learn Med 1995;7(1):37–42.

9. Alnasir F, Grant N. Student self-assessment in a community based clinical clerkship in family medicine. Health Educ J 1999;12(2):161–6.

10. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [cited: 2015 June 19].Available from: http://www.essentialevidenceplus.com.

11. Thompson BM, Rogers JC. Exploring the learning curve in medical education: using self-assessment as a measure of learning.Acad Med 2008;83(10 Suppl):S86–8.

12. Rogers J, Dains J, Corboy J, Chang T. Curriculum renewal and a process of care curriculum for teaching clerkship students. Fam Med 1999;31(6):391–7.

13. Rogers J, Corboy J, Dains J, Huang W, Holleman W, Bray J, et al. Task-oriented processes in care (TOPIC): a proven model for teaching ambulatory care. Fam Med 2003;35(5):337–42.

14. American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians, American Osteopathic Association. Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. February 2007 [cited: 2015 Apr 29]. Available from:www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/practice_management/pcmh/initiatives/PCMHJoint.pdf.

Department of Family and Community Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston,TX, USA

William Huang, MD

Department of Family and Community Medicine, 3701 Kirby Drive, Suite 600,Houston, TX 77098, USA

Tel.: +713-798-6271

E-mail: WilliamH@bcm.edu

3 April 2015;

4 May 2015

Family Medicine and Community Health2015年2期

Family Medicine and Community Health2015年2期

- Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- Evaluation of obstetrics procedure competency of family medicine residents

- Depression and race affect hospitalization costs of heart failure patients

- Rural congestive heart failure mortality among US elderly,1999–2013: Identifying counties with promising outcomes and opportunities for implementation research

- Exploring point-of-care transformation in diabetic care: A quality improvement approach

- Hospitalizations and healthcare costs associated with serious,non-lethal firearm-related violence and injuries in the United States,1998–2011

- Adult immunization improvement in an underserved family medicine practice