Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections: What impacts treatment duration?

Adam Przyby?kowski , Piotr Nehring

Department of Gastroenterology and Internal Medicine, Medical University of Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland

ARTICLE INFO Article history:Received 21 October 2021 Accepted 30 March 2022 Available online 6 May 2022

Keywords:Cyst Drainage Endoscopy Pancreas Pancreatitis

ABSTRACT Background: Peripancreatic fluid collections (PFCs) are complications resulting from acute or chronic pancreatitis and require treatment in certain clinical conditions. The present study aimed to identify the factors influencing the duration of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided drainage of symptomatic pancreatic pseudocysts (PPCs), walled-off necrosis (WON), and acute necrotic collections (ANCs).Methods: This was a retrospective cohort study of 68 patients with PFCs who underwent EUS-guided drainage. The timing and duration of EUS-guided drainage of various PFCs (ANC, WON, and PPCs) were compared, and the factors influencing the duration of endoscopic treatment were identified.Results: The mean time to first EUS-guided PFC drainage since the acute pancreatitis episode was 372.0,505.0, and 18.7 days for WON, PPC, and ANC, respectively, and the mean duration of treatment was 90,60, and 63 days, respectively. A disconnected pancreatic duct, a history of percutaneous drainage, and an infected PFC were identified as factors influencing the treatment duration. A positive correlation was observed between the treatment duration and patients’ age. Patients with a disconnected pancreatic duct had to undergo more procedures. In patients with PPC, clinically successful drainage was more frequently achieved after a single procedure without the need for repeated procedures than in those with WON(90% vs. 59%, P = 0.01).Conclusions: Patients with a history of percutaneous drainage, disconnected pancreatic duct, or PFC infection may require longer endoscopic treatment.

Introduction

Pancreatic and peripancreatic fluid collections (PFCs) are a heterogeneous group of lesions that may arise following an episode of acute pancreatitis, acute-on-chronic pancreatitis, exacerbation of chronic pancreatitis, or pancreatic trauma [1-3] . Based on the presence of necrotic or nonnecrotic collection and the time from the onset of symptoms (usually<4 or>4 weeks), the Atlanta Classification of Acute Pancreatitis (2012 revision) has distinguished PFCs into 4 distinct forms: acute peripancreatic fluid collection (APFC),pancreatic pseudocyst (PPC), acute necrotic collection (ANC), and walled-off necrosis (WON) [4] . APFC and ANC develop in the early phase of pancreatitis, i.e., within 4-6 weeks, and do not have a defined wall, whereas PPC and WON usually appear after 4-6 weeks and are contained within a thick wall [4] . The main goal of interventions used for PPC or WON is to relieve symptoms and avoid late complications [5] . It has been proven that endoscopic procedures result in shorter hospital stays and a lower incidence of pancreatic fistula than open surgery [6] . Several methods may be applied in the endoscopic approach [7] . For gastro- or duodenocystostomy, the most commonly used stents are double-pigtail plastic prostheses, self-expandable metallic stents (SEMS), and lumenapposing metallic stents (LAMS). The typical endoscopic procedure involves incision (with needle and/or cystotome), gastrocystostomy dilatation (with dilators, balloons), and lumen collapse prevention(with one or more stents). Age, acute pancreatitis etiology, underlying pancreatic disorder, and cyst size and localization vary in patients developing PPC and/or WON. These factors may also influence the choice of treatment approach, type of endoscope used, type and number of stents used, and number of prostheses inserted, as well as the decision to perform pancreatic duct drainage.

Thus far, no large study has been carried out exploring the factors affecting the duration of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided treatment of PFC. Moreover, the available studies have not focused on the determination of appropriate follow-up schedules and PFC treatment duration, which are based on clinical practice, expert recommendations, and individual unit experience.

According to the European Society of Gastroenterology and Endoscopy (ESGE) guidelines for WON, invasive intervention should be performed 4-8 weeks after the onset of acute pancreatitis [ 8 , 9 ].The number of endoscopic necrosectomy sessions needed for the treatment of WON varies between 1 and 15 (mean = 4) [ 9 , 10 ].The ESGE guidelines recommend that PPC should be treated in individuals with chronic pancreatitis if they are symptomatic [11] .Transmural plastic stents should be retrieved after 6 weeks of PPC regression at the earliest in the absence of disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome, whereas long dwelling of the stent is recommended if the syndrome is present [ 11 , 12 ]. According to the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) guidelines,drainage of acute PFCs and ANCs should be delayed after 4 weeks to allow the margins of fluid collection to be clearly visible [13] .The guidelines propose that computed tomography (CT) scans be made 4-6 weeks after the procedure and that stents be eventually removed when PFC resolution is documented [14] . The guidelines provide recommendations when to start endoscopic treatment and when to consider stent removal; nevertheless, there are only a few studies on the duration of endoscopic treatment.

This study aimed to compare the timing and duration of EUSguided drainage of various PFCs (ANC, WON, and PPCs) and to identify the factors influencing the duration of endoscopic treatment.

Methods

Patients

This was a retrospective analysis of patients who underwent EUS-guided drainage for PFC in the Department of Gastroenterology and Internal Medicine, Medical University of Warsaw, Poland,between January 2012 and December 2020.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Warsaw, Poland. All methods applied in the study were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was waived as the study was based on medical history and patient records, without involving any interventions or possible risks to patients.

Acute pancreatitis was diagnosed based on Atlanta clinical criteria, which require at least two of the following: epigastric pain, elevated levels of pancreatic enzymes, or typical imaging presentation [3] . Chronic pancreatitis was diagnosed based on the guidelines of United European Gastroenterology and the working group on “Harmonizing diagnosis and treatment of chronic pancreatitis across Europe”(HaPanEU) [14] . The classification of PFC was based on the Atlanta Classification for Acute Pancreatitis (2012 revision) [ 3 , 4 , 15 ].The indications for endoscopic intervention were proven or suspected PFC infection (i.e., gas in imaging examination, positive hemoculture, and/or signs of systemic inflammatory response syndrome or sepsis), mass effect of PFC, or abdominal compartment syndrome [9] . According to the recent recommendations for the management of WON, the drainage of pancreatic necrosis was deferred until the completion of the walled-off process, as confirmed by EUS or CT, which usually takes approximately 4 weeks [16] .

Disconnected pancreatic duct was diagnosed by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography or EUS based on the appearance of a connection between the PFC and pancreatic duct.

Technically successful drainage was defined as the completion of the placement of an acting plastic stent and/or a SEMS into the PFC through the formed tract without the incidence of an early complication. An early complication was defined as a complication diagnosed during the procedure or within 24 h after the procedure.

The total duration of endoscopic treatment was defined as the interval between the first drainage and the final removal of stent(s). Clinically successful drainage was described as complete recovery from PFC without complications necessitating surgical treatment during the follow-up of 12 weeks. On the other hand,failure was defined as a complication resulting from drainage or recurrence of fluid collection requiring a surgical approach. Some patients required several procedures, such as necrosectomy or nasocystic tube placement; however, this was not regarded as a failure but rather as a natural course of the endoscopic approach.

All patients were monitored for 12 weeks.

Therapeutic procedure

Echoendoscopes with an oblique view [UCF 180 or UCF 140(Olympus, Tokyo, Japan)] were used for EUS. The fluid collection lumen was accessed via a 19-G biopsy needle (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA or Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, NC,USA), and a sample of aspirated contents was collected for biochemical examination and culture. Following sample collection, the guide wire (Olympus) was introduced, and gastrocystostomy dilatation was performed using either gastrocystotomy (6 Fr Endo-Flex GmbH, Voerde, Germany) or 4-10 Fr dilatators (Cook Medical). When necessary, balloon dilatation was performed using a 10-12 Fr balloon (Boston Scientific). Depending on the content and anatomical condition of cysts, either a plastic stent (Boston Scientific) or a SEMS (Hanarostent BCF Niti-S, Taewoong Medical, Seoul,Korea) was implanted. Attempts were made in all cases to empty the fluid lumen during the initial procedure through endoscope suction or by placing a 7 Fr Liguory? nasocystic tube (Cook Medical). Following the placement of the nasocystic tube, flushing was performed for 1-3 days with 100 mL of 9% NaCl solution 5 times per day. Metal-covered and plastic stents were not simultaneously placed during the same procedure in any patient; however, in a few cases, plastic stents were replaced with metal stents during follow-up.

Follow-up plan

Imaging studies (ultrasound examination, CT, or magnetic resonance) were performed at 2-week intervals after the endoscopic procedure until PFC resolution was achieved. Early stent removal was preferred in patients in whom PFC resolution was confirmed by imaging studies. In patients who did not show PFC resolution, according to the step-up approach, depending on the density of fluid/necrosis, insertion of additional plastic stents, endoscopic necrosectomy, insertion of a nasocystic tube, and lavage were performed, or the stents were leftinsitufor another month. Patients in whom pancreatic duct leakage was observed on follow-up imaging (disconnected pancreatic duct) qualified for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with pancreatic duct stenting or transpapillary PFC drainage. Follow-up was continued for all patients with imaging studies at 3- to 6-month intervals.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were identified based on their distribution. Student’sttest was used for normally distributed variables, while the Mann-WhitneyUtest was performed for nonnormally distributed variables. For the analysis of categorical variables, the Chi-square test was used with Fisher’s correction in the case of small samples. Missing data were removed in pairs. Statistical significance was considered atP<0.05. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed using the Hooke-Jeeves and Quasi-Newton estimation methods. Multiplegroup analysis was performed using analysis of variance or the Kruskal-Wallis test, as appropriate. Statistical analysis was per-formed using Statistica software (TIBCO Inc., version 13; Dell Inc.,Tulsa, OK, USA).

Results

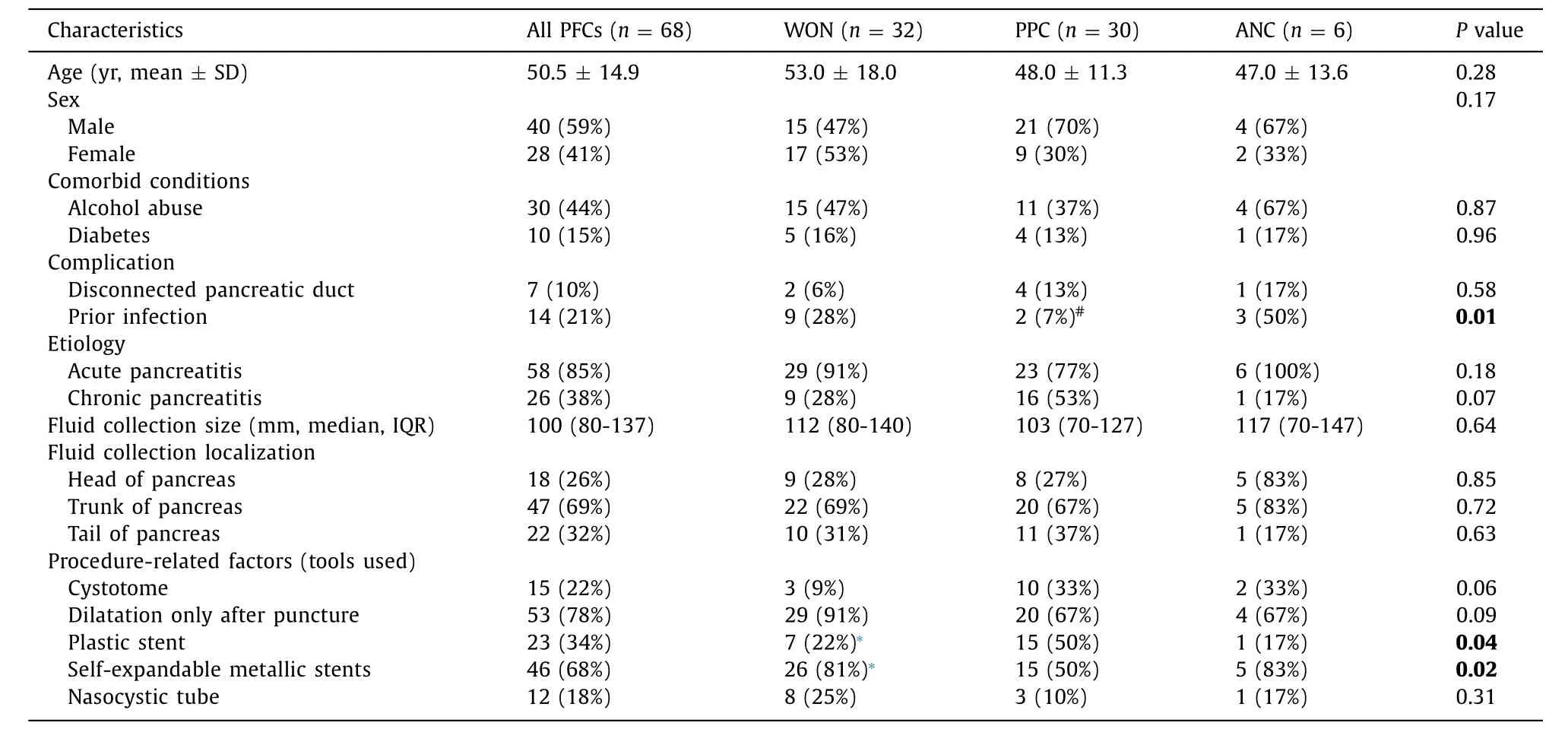

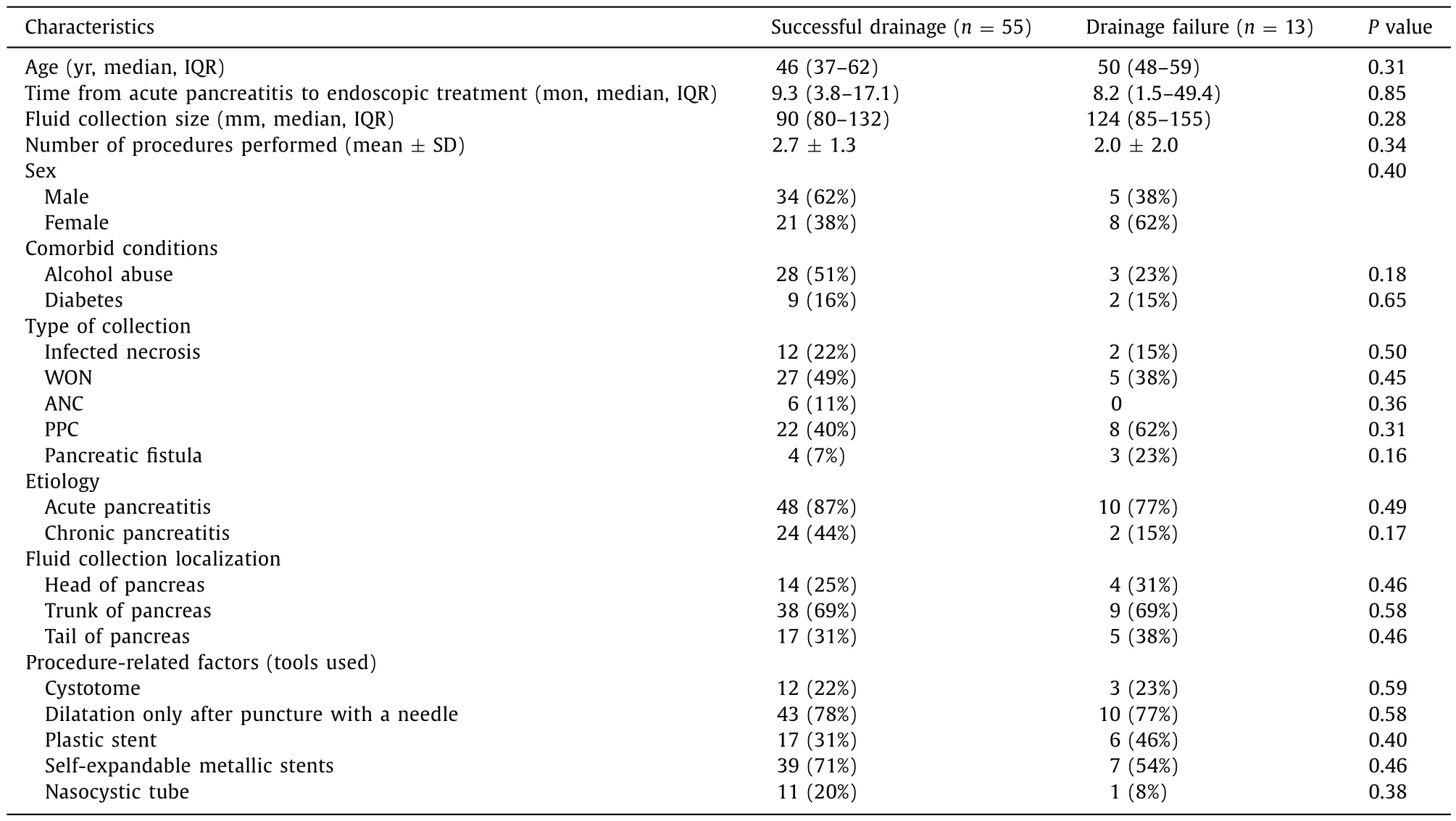

A total of 75 patients were initially involved in the study. Seven(9%) patients were lost to follow-up and thus were not included in the analysis. The characteristics of the studied group of patients are presented in Table 1 .

Table 1 Characteristics of the studied groups.

No significant differences in age, sex, prevalence of alcohol use or diabetes, or localization and size of PFC were observed between patients with WON, PPC, and ANC. Prior infection of the PFC was found to be more frequent in patients with ANC than in those with PPC; however, there was no significant difference in prior PFC infection incidence between ANC and WON. Plastic stents were more frequently used in PPC than in WON (50% vs. 22%), while SEMSs were less frequently used in PPC than in WON (50% vs. 81%) (allP<0.05) ( Table 1 ).

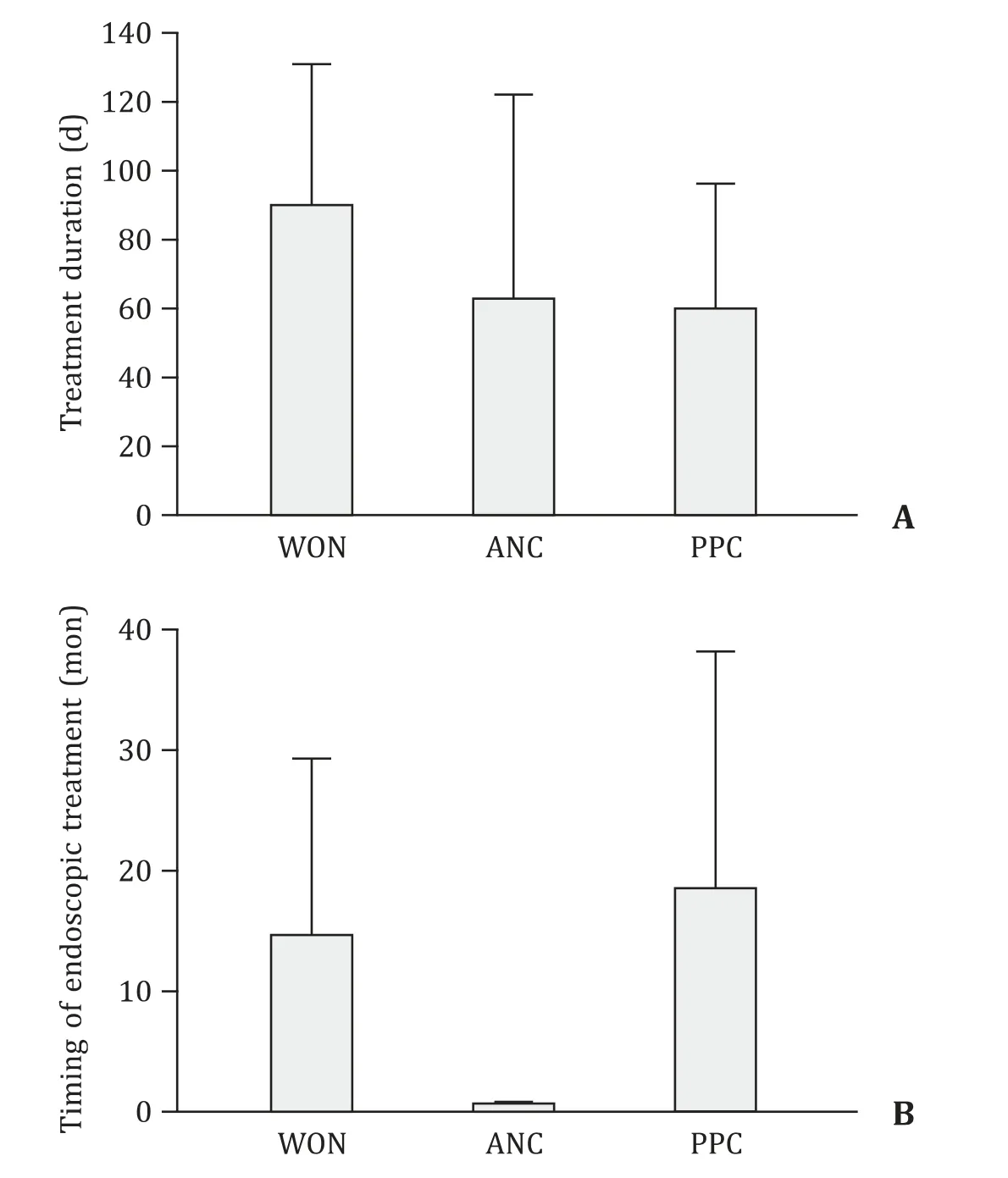

Treatment duration

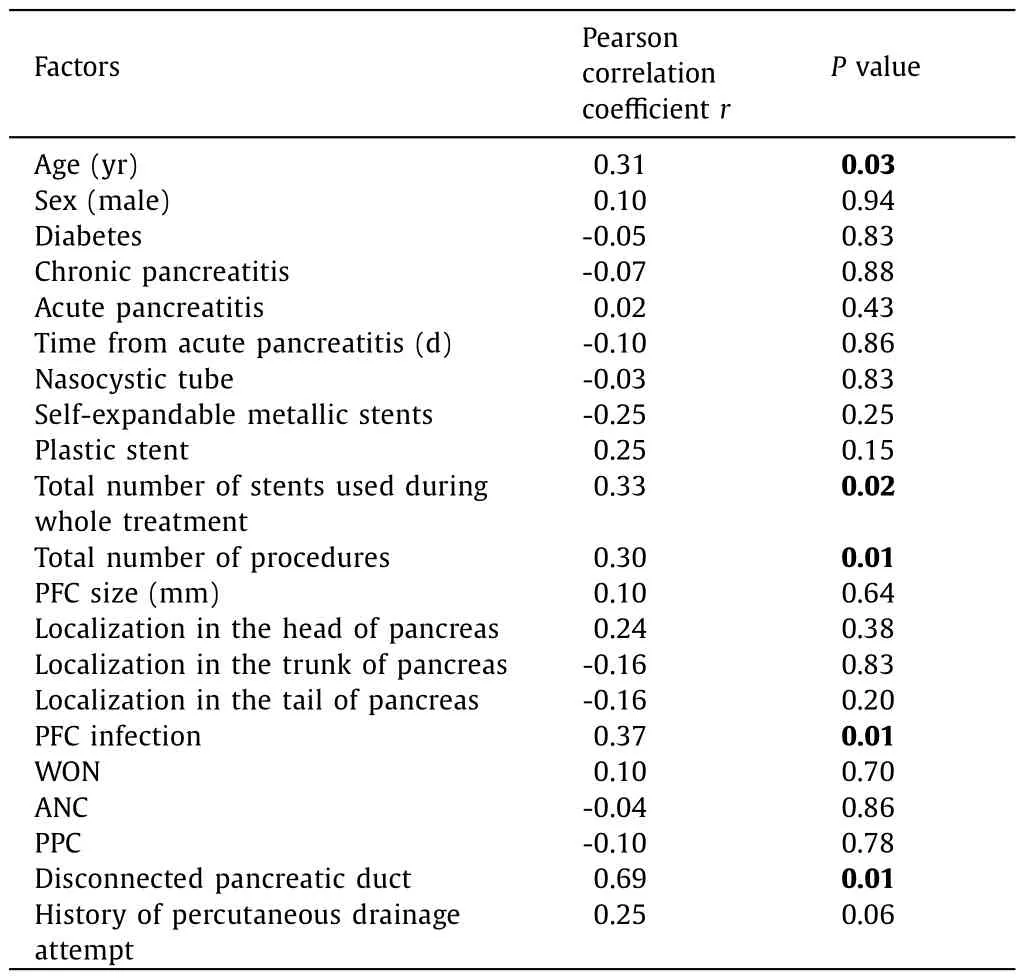

The mean duration of endoscopic treatment was longest in the WON group (90 days) and shorter in the PPC group (60 days) and ANC group (63 days), but the differences between groups were not statistically significant ( Table 2 , Fig. 1 A and B). However, when analyzing a single factor (variable) in the whole studied population,the duration of treatment was longer in patients with a disconnected pancreatic duct (191 ± 73 vs. 57 ± 33 days;P= 0.01), history of percutaneous PFC drainage (238 ± 75 vs. 60 ± 37 days;P= 0.06), or infected PFC (91 ± 61 vs. 55 ± 30 days;P= 0.01).It was observed that treatment duration correlated positively with the age of patients (P= 0.03). Furthermore, the duration of PFC treatment correlated with the number of stents used and the number of endoscopic procedures required ( Table 3 ).

Fig. 1. Peripancreatic fluid collection treatment with endosonography-guided drainage in different patient groups. A: Duration of endoscopic treatment in patient groups; B: timing of endoscopic treatment in patient groups. WON: walled-off necrosis; PPC: pancreatic pseudocyst; ANC: acute necrotic collection.

Table 3 Correlation matrix for factors affecting the PFC treatment duration.

Six (100%) patients with ANC underwent EUS-guided drainage of the PFC within the 4th week of the acute pancreatitis episode.The mean time of EUS-guided PFC drainage since the acute pancreatitis episode was 372.0 ± 450.0 days in patients with WON,505.0 ± 494.0 days in patients with PPC, and 18.7 ± 3.4 days in patients with ANC.

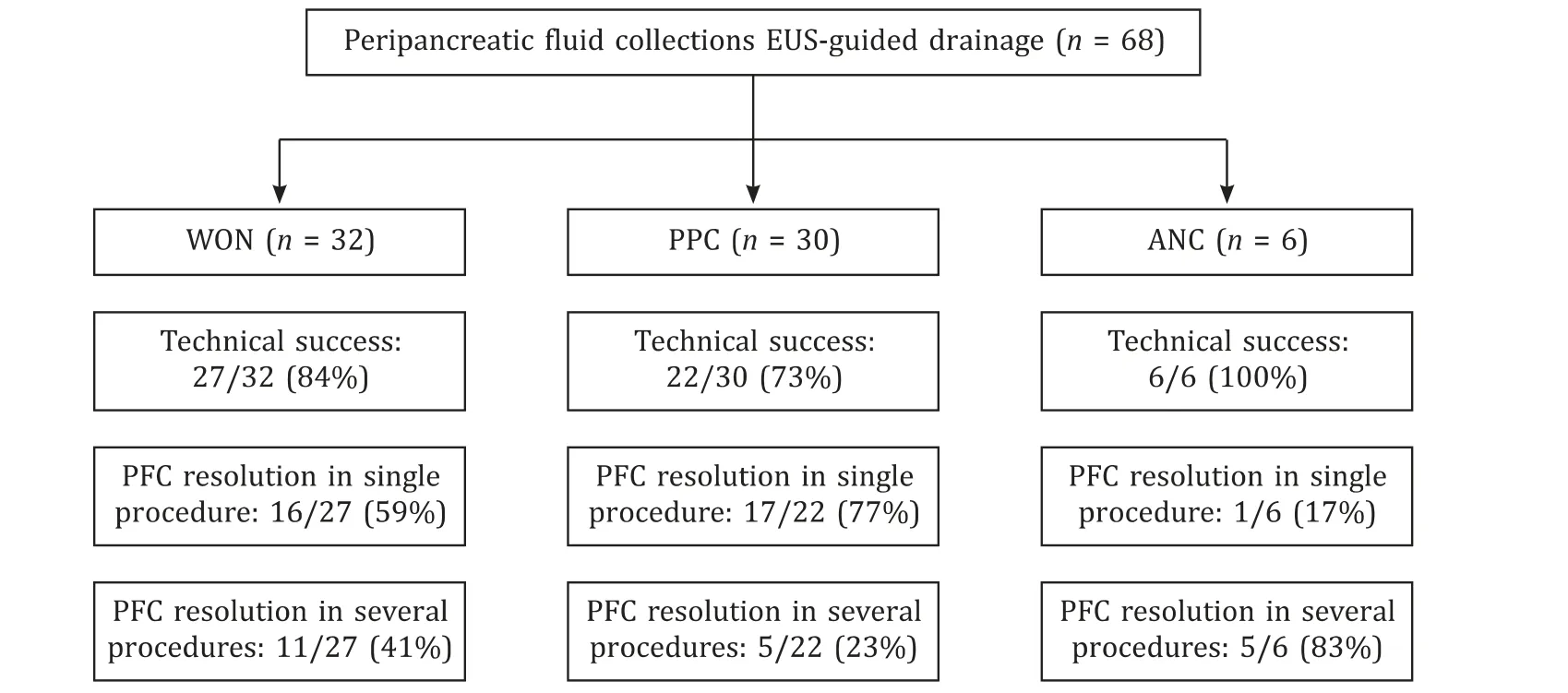

Number of endoscopic procedures

The general clinical and technical success of the endoscopic procedure was not significantly influenced by the examined factors ( Table 4 ). A total of 142 procedures were performed in 68 patients. Technically successful drainage was achieved in 55 patients (81%, 55/68). A single procedure was sufficient in 34 patients(62%, 34/55), whereas 21 patients (38%, 21/55) required repeated endoscopic treatment. In the WON group, technically successful drainage was achieved in 84% (27/32), of whom 16 (59%) required a single procedure and 11 (41%) required multiple procedures. In the PPC group, technically successful drainage was achieved in 73%(22/30), of whom 17 (77%, 17/22) required a single procedure and 5 (23%, 5/22) required several procedures. In the ANC group, technically and clinically successful drainage was achieved in all 6 patients, of whom a single endoscopic procedure was performed in one (17%) and repeated procedures were performed in 5 (83%) patients ( Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2. The percentage of the effectiveness of endosonography-guided drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections depending on the collection type. EUS: endoscopic ultrasound; PFC: peripancreatic fluid collection; WON: walled-off necrosis; PPC: pancreatic pseudocyst; ANC: acute necrotic collection.

Table 4 Clinical characteristics of patients who were successfully treated and who failed endoscopic treatment.

Clinically successful drainage was more easily achieved (with a single procedure) in patients with PPC than in patients with WON[20/22 (91%) vs. 16/27 (59%);P= 0.01]. The use of a cystotome was required more frequently in patients with PPC compared to the WON group (3/32 in WON and 10/30 in PPC,P= 0.02).

In the group of 21 patients (11 with WON, 5 with ANC, and 5 with PPC) who required several procedures, 11 (52% out of 21) had one or more endoscopic necrosectomies, 8 (38% out of 21) underwent replacement of the prosthesis (bigger plastic stent or SEMS),3 (14% out of 21) had additional transpapillary PFC drainage, and 2 required (10% out of 21) nasocystic tube placement.

In patients who required several procedures, the mean time interval between endoscopic procedures was 36.0 ± 20.0 days in the WON group, 49.3 ± 20.4 days in the PPC group, and 18.0 ± 6.8 days in the ANC group.

Patients with a disconnected pancreatic duct underwent more EUS-guided drainage procedures than those without pancreatic fistula (5.3 ± 1.5 vs. 1.7 ± 1.3;P<0.001).

Risk of complications

Ten (14.7%) patients suffered from procedure-related complications (perforation,n= 5; bleeding,n= 3; stent migration,n= 1; infection,n= 1), and all of them required open surgery.No periprocedural deaths were recorded in the studied group.Procedure-related complications occurred in patients with a larger PFC (140.9 ± 40.9 vs. 101.8 ± 38.3 mm; OR = 1.02, 95% CI: 1.01-1.04;P= 0.01). This means that every millimeter increase in the size of the PFC increased the risk of complications by 2%. Complications were more frequent in patients without chronic pancreatitis than in patients with underlying chronic pancreatitis (9/42 vs.1/26;P= 0.047; RR = 5.57, 95% CI: 0.75-41.47). In 2 patients with PPC, recurrence of PFC was observed, one in a short-term followup (60 days) and one in a long-term follow-up (2 years). The risk of periprocedural complications was not dependent on the duration between the acute pancreatitis episode and PFC treatment.

Discussion

The advantage of EUS-guided PFC drainage as the first-line approach has been demonstrated in previous studies comparing endoscopic treatment with percutaneous drainage and the surgical approach [17-22] . It has been reported that PPC can be successfully drained in 82%-89% of cases, while complications can occur in 5%-16% and recurrence in 4%-16% [23] . In the present study, the technical success rate was 84%, and the complication rate was 14.7%.Recurrence of PFC was noted in only 2 out of 55 patients with PPC(3.6%), with one in the short-term follow-up (60 days).

According to surgical studies focusing on the timing of intervention in necrotizing pancreatitis, the timing of endoscopic intervention should be delayed until at least 4 weeks after the initial presentation. This indicates that an open necrosectomy is associated with poor prognosis when performed early [ 23 , 24 ].PPCs usually form at least 4-6 weeks after an acute pancreatitis episode [25] . A further delay in drainage beyond 8 weeks may increase the risk of developing complications [26] . Currently, it is recommended that endoscopic drainage should not be performed until PFC has become encapsulated (4 weeks of latency) due to the higher risk of complications [ 3 , 9 ]. In the study of Trikudanathan et al. on patients with necrotizing pancreatitis treated with endoscopic drainage, an early approach (up to 4 weeks) was associated with higher postprocedural mortality, longer hospital stays,and risk of pancreatic fistula formation compared to the standard approach (delayed by more than 4 weeks) [24] . However, the timing of drainage placement was separately assessed by the welldesigned POINTER trial conducted by van Grinsven et al. [25] . In the present study, in 6 patients with ANC, endoscopic drainage was performed earlier than 4 weeks (28 days) from cyst formation due to the diagnosis of mass effect. In all these cases, the mass effect caused duodenal obstruction resulting in upper gastrointestinal obstruction, with nausea and vomiting as dominating symptoms. Among the 6 patients, complications (i.e., stent migration during initial gastrocystostomy) were observed in one, which was treated by stent removal and replacement within the same procedure.

The ESGE guidelines on PPC recommend that in the absence of disconnected pancreatic ducts, stent retrieval can be performed after 6 weeks [ 11 , 26 ]. According to Barthet et al., the duration of PPC treatment varies, with a median of 4.4 months [27] . In the present study, the mean duration of treatment was 2 months for PPC and approximately 3 months for WON.

After an episode of acute pancreatitis complicated with WON,most of the patients require interventional treatment. According to the ESGE and ASGE guidelines, the duration of endoscopic treatment for WON is determined by the effect of drainage as assessed by imaging studies [ 9 , 13 ]. A worldwide multi-institutional survey indicated that the mean optimal interval recommended for endoscopic necrosectomy procedures following EUS-guided drainage was 6.23 days (range 3-21) [28] . The EUS Journal Consensus survey highlighted that the optimal interval for repeated imaging studies in follow-up was 12.32 ± 7.46 days, and stent removal was performed after 4.59 ± 1.92 weeks [28] . In the study of Gornals et al.,the resolution of WON was assessed by CT or EUS after 4-8 weeks of drainage, and the mean time to stent retrieval was 9.0 ± 3.4 weeks [29] . In the present study, imaging was performed at 2-week intervals after the endoscopic procedure until the PFC was resolved.

The mean time interval between repeated endoscopic procedures was 36.0 ± 20.0 days for WON, 49.3 ± 20.4 days for PPC,and 18.0 ± 6.8 days for ANC, which is in line with the EUS Journal Consensus survey and does not differ between patient groups with different types of PFC [28] . The timing of the next endoscopic treatment session was determined based on the patient’s general condition (if poor, the procedure was performed earlier)and the results of follow-up imaging studies (size and content of PFC).

Thus far, no studies have compared the treatment duration and endoscopic methods applied in PPC and WON patients after an acute pancreatitis episode. Moreover, no studies have assessed the methods and duration of PPC treatment depending on etiology(chronic vs. acute pancreatitis). In the present study, the duration of PFC treatment until its resolution was found to be longer in patients with a disconnected pancreatic duct, those who had previously undergone percutaneous drainage, and those with infected PFC. In several patients, more than one endoscopic procedure was performed according to the step-up strategy of PFC management.A disconnected pancreatic duct was associated with an increase in the number of procedures performed and thus prolonged PFC treatment.

A positive correlation was found between the drainage duration and patient age. In general, a longer treatment duration was associated with additional procedures and the number of stents implanted to achieve PFC resolution. Therefore, it is important to define the factors that influence the technical and clinical success of PFC drainage at the first procedure. In the present study,successful drainage with no complications was achieved in 81%of patients, while complications occurred in 16%, which is in line with previous studies [ 8 , 10 , 12 , 17 ]. Complete PFC resolution was more easily achieved in patients with PPC than in those with WON.

It should be noted that none of the patient-related factors correlated with final drainage efficacy. The present study did not show any advantage of plastic or SEMS. However, the study of Ge et al.showed that, compared to LAMS, implantation of plastic stents led to a significantly increased risk of reintervention in the presence of large cysts [30] . The advantage of LAMSs over plastic stents was also demonstrated in the study of Yang et al. [31] . However, a recent meta-analysis showed that LAMS and plastic stents were associated with similar clinical outcomes and adverse events in the drainage of pancreatic WON [32] .

The present study confirmed that EUS-guided drainage has a high rate of success and a low number of complications, which complies with the findings of other studies [ 33 , 34 ]. Compared to other publications, the patient group in this study was relatively large; however, the absolute number of cases may be insufficient for robust statistical analysis, which is a limitation of the study.The heterogeneity of the studied group consisting of patients with complications of both acute pancreatitis and chronic pancreatitis and patients with PPC, WON, and ANC may also be considered a limitation; however, the heterogeneous nature of the study group allowed us to perform a comparative analysis. It is necessary to carry out further investigation of risk factors influencing the duration and efficacy of PFC endoscopic drainage in the cases of WON and PPC separately to develop individualized therapeutic approaches for these groups. Knowledge of the appropriate timing,duration, and interval of endoscopic procedures will help in the proper planning and execution of PFC treatment.

In conclusion, the duration of EUS-guided PFC drainage was correlated with the patient’s age and the presence of local complications (disconnected pancreatic duct, infected PFC, and history of percutaneous drainage). Patients with a disconnected pancreatic duct will likely require more procedures to achieve PFC resolution.Moreover, the type of PFC was not the most important factor affecting treatment duration.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Peter Roman from Philadelphia, PA, USA for proofreading and support in critically reviewing the manuscript and Translmed Publishing Group, Wielu ′n, Poland for proofreading.

CRediTauthorshipcontributionstatement

AdamPrzyby?kowski:Conceptualization, Funding acquisition,Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.PiotrNehring:Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis,Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

This study was supported by statutory activity of the Medical University of Warsaw, Poland.

Ethicalapproval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Warsaw, Poland.

Competinginterest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2023年3期

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2023年3期

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Narrative medicine principles and organ donation communications

- Hepatobiliary&Pancreatic Diseases International

- Laparoscopic extended right hepatectomy for posterior and completely caudate massive liver tumor (with videos)

- Etiology and classification of acute pancreatitis in children admitted to ICU using the Pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (pSOFA)score

- Percutaneous ultrasound and endoscopic ultrasound-guided biopsy of solid pancreatic lesions: An analysis of 1074 lesions

- Increased incidence of indeterminate pancreatic cysts and changes of management pattern: Evidence from nationwide data