Ultrasound Visual Biofeedback and Accent Modification: Effects on Consonant and Vowel Accuracy for Mandarin English Language Learners

ARMSTRONG Courtney Beth,RUSIEWICZ Heather Leavy,MICCO Katie,CHEN Yang

1 Speech-Language Pathology, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15282, USA;

2 Duquesne-China Health Institute, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15282, USA

KEY WORDS accent modification;ultrasound;Mandarin;English

1 Introduction

English language learners(ELLs)often face challenges when communicating, due in part to disparate phonetic inventories which lead to accented speech.Because accented speech may impact the effectiveness of one’s professional and social communication exchanges, individuals might choose to address such challenges with the support of speech-language pathologists (SLPs). However, empirical evidence regarding intervention for accent modification services in speechlanguage pathology (SLP) is limited. Consequently,there is a call to expand investigations of accent management and integrate speech therapy approaches with established empirical evidence from interventions such as ultrasound visual biofeedback. This technique has been implemented with a variety of speech sound disorder diagnoses, but not yet empirically studied as an accent modification technique for native Mandarin speakers. Thus, this study aimed to provide the first data on the impact of ultrasound visual biofeedback paired with perceptual training on the accuracy of phonemes produced by individuals who spoke Mandarin as their first language. This study is also among the first to examine the effect of ultrasound visual biofeedback for vowel production.

1.1 Impact of accent

According to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association[1], accent is a ‘the unique way that groups of people who speak the same language sound’.It is well-established that accented speech is not to be viewed or trained as a communication disorder. Yet,accented speech can lead to reduced intelligibility and psychosocial consequences.Cheng[2]commented that,‘a(chǎn)ccents and variations have social, economic, emotional and political implications’. On an individual level, an accent can influence a person’s involvement in society. According to the Los Angeles Times, ‘a(chǎn)ccent reduction students said they are self-conscious about how they sound and whether their accents are limiting their job opportunities or stunting their social lives’.Moreover,Fitch[3]commented that accent modification gives employees‘a(chǎn)n economic edge’.Recently,a study by Hosoda and Stone-Romero[4]explored the effects of foreign accents on employment-related decisions of 286 college students who spoke with mainstream American English, French and Japanese accents. Listeners decided to hire participants based on accent, understandability, and communication demands after mock interviews. Results from this study found Japanese-accented applicants to have the least success in being considered for the position due to their accent.Hosoda and Stone-Romero[4]noted, ‘they were evaluated more negatively when they applied for jobs that had high communication demands,regardless of job status’.As the world continues to connect crossculturally and cross-linguistically, it is important to better understand supports for those who seek out ways to optimize their communication. Within the United States, it is also especially important to provide evidencebased practice for accent modification services focused on languages that are frequently spoken other than English,such as Mandarin.

1.2 Mandarin prevalence in the USA

The USA continues to experience an amalgamation of not only of cultures, but languages. Shin and Ortman[5]stated, ‘the use of a language other than English at home increased by 148 percent between 1980 and 2009’.The USA 2010 census projected Mandarin to be the second-most commonly spoken language other than English (LOTE) in America by 2020[5-6].

There are several phonetic differences between American English and Mandarin. Mandarin does not include consonant clusters or multisyllabic canonical shapes. Closed syllables are uncommon and only two consonants, /n/ and /?/, occur in the final position.Eight American English phonemes are not found in Mandarin: /v/, /z/, /?/, /?/, /?/, /?/, /θ/ and /e/[7].Common American English substitutions produced by Mandarin speakers include: /s/ or /f/ for /θ/, /d/ or /z/for/e/and/f/or/w/for/v/[7].Likewise,Mandarin and American English differ in their vowel inventories. In Mandarin, there are six vowels; /i/, /e/, /j/, /u/, /o/ and/ɑ/[8]in contrast to the 11 vowels of American English:/i/,/I/,/ε/,/e/,/o/,/?/,/u/,/?/,/?/,/ɑ/and/?/[9].Several phonemes, such as /I/, are unfamiliar to native Mandarin speakers.

Liquids are of particular interest in these languages because of the variations in pronunciation and frequency of use of /r/ and /l/ in American English. According to Smith[10], ‘Mandarin /l/ is a voiced apical denti-alveloar or apical alveolar lateral approximant and /r/ is an apical post-alveolar retroflex approxi mant’.In contrast,Smith[10]wrote, ‘in American English, /r/ is a voiced alveolar approximant and /l/ is a voiced alveolar lateral approximant…[U]nlike English/r/,Mandarin/r/has little or no lip rounding and is produced with greater constriction,resulting in audible friction noise in some dialects and vowel contexts’.Although both languages have liquid consonants,articulation characteristics differ, thus creating challenges for a native Mandarin speaker. Anecdotally, an unfamiliar American English listener will perceive a vocalic /r/ as a derhotacized /r/. This perception will influence production so that vocalic/r/s is produced as derhotacized /r/s, thus impacting intelligibility. Because the/r/phoneme is produced within the oral cavity,it is challenging to cue and improve production unless viewed with technology similar to ultrasound visual biofeedback.

1.3 Current accent modification approaches

Despite the longevity and importance of accent modification services in the profession of speech-language pathology, there are few established interventions with supporting empirical data.One technique is the Compton Pronouncing English as a Second Language (ESL) Program[11]which aims at ‘creat[ing]new speech habits, so new sounds will be produced automatically’.Training is based on group therapy and emphasizes pragmatic skills,leaving little room for individualization or targeting speech production differences. Traditional articulation and phonological approaches have been implemented successfully[12-13].However, there is no explicit difference noted for either approach[14].Segmental and prosodic approaches have also been successful in improving suprasegmental aspects of speech but do not focus on the underlying phonetic differences that impact intelligibility[14].The Clear Speech approach has also been used frequently in accent modification treatment. This approach conjectures that over-enunciation produces the most intelligible speech[15-17]. The Clear Speech approach has been used to improve unintelligibility stemming from various etiologies such as Parkinson’s disease, laryngectomies, multiple sclerosis, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis among others. Findings from these studies suggest that intelligibility of speech and ease of understanding accented speech improve based on enunciation. But again, although this approach could positively influence an accent modification intervention, it does not target specific articulation differences. Additionally, biofeedback approaches rely on external devices to provide feedback about various speech production characteristics[18]. Results from these approaches demonstrate that phonetic training was effective with combined traditional and visual feedback.

Most of the accent modification approaches mentioned also used visual feedback or cues to improve the ability of participants to produce differences in phoneme production[11,13-14,18]. Moreover, Schmidt[19]commented that ‘before the existence of books, it is likelythat second language learners listened to,watched and imitated native speakers...visual methods of training were developed when imitation of a live native speaker was not possible’.Thus,it is natural to rely on visual methods,such as ultrasound biofeedback, while learning new articulation patterns.

1.4 Underlying mechanism of accented speech

It is imperative that individuals dually train the accurate production of non-native phonemes in accent modification services. One theory posits that accented speech occurs due to an inability to perceive phonetic differences which influence motoric production of foreign phonemes. According to Shafer, Shucard, and Gerken[20],‘infants are sensitive to differences between(the)two language conditions’.As adulthood is reached,individuals lose their ability to discriminate between native and foreign phonemes making it challenging to produce sounds needed to fluently articulate another language. Schmidt[19]wrote, ‘listeners had difficulty hearing the distinctions they were trying to learn to produce’.For example,a native Mandarin speaker will likely perceive and produce a Mandarin/r/and American English/r/as the same because they are unfamiliar with the subtle perceptual differences. Interestingly,research also highlights the complex integration of perceptual and motor processes,such that speech motor regions of the brain (e.g., Broca’s area) are activated when listening to phonetic contrasts in a second language[21].Thus,it is important to train not only the articulatory production of the speech sound targets, but also the perceptual differences. Therefore, this study unified the articulatory-production focused use of ultrasound and perceptual discrimination tasks.

1.5 Roles of ultrasound visual biofeedback in speech-language pathology

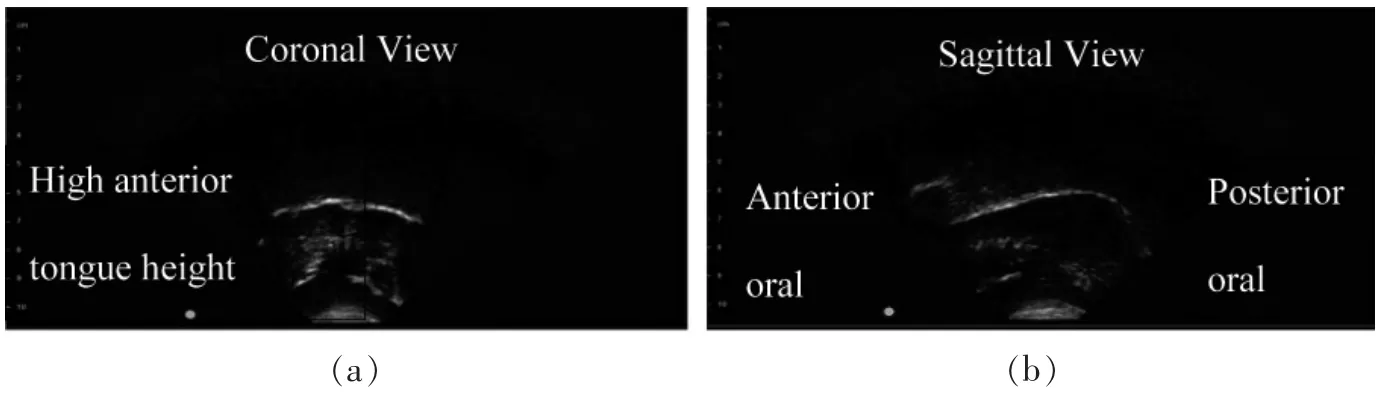

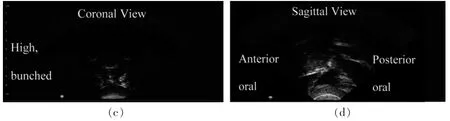

Ultrasound imaging relies on high-frequency sound waves emitted by a probe to create an image of the tongue allowing clients to ‘learn visually’ by seeing how their tongue moves for certain sounds[22].The visual images provide information about articulation properties of various phonemes from two different views, sagittal and coronal (see figures 1 and 2)[23].Preston, Holliman-Lopez and Leece[24]noted that ultrasound was used for a plethora of disorders and was associated with positive patient satisfaction,regardless of the population. Multiple types of feedback and analyses provide the client with the best information about how their articulators work. Tactile/kinesthetic feedback can also be paired with ultrasound biofeedback for more robust therapy[25]. This technology is also less invasive, cost-effective, easy to understand and portable[26].

Figure 1 Ultrasound image of /l/ phoneme production

Figure 2 Ultrasound image of /r/ phoneme production

1.6 Ultrasound visual biofeedback for vowel and rhotic production

Though research on ultrasound technology has surged in recent years,studies have focused on the effect of visual biofeedback on consonants produced by children, adolescents, and adults with speech sound disorders.To date,there is limited investigation of the effect of ultrasound biofeedback and vowel produc-tion, and only in reference to pronunciation training and not yet in Mandarin.Yet,it can be argued that this technology is particularly useful when targeting vowels because it allows one to see tongue height, placement, and tension that is otherwise not visible to the client.

For example, Tsui[27]saw a benefit of using ultrasound biofeedback as a technique for improving American English liquids (i.e. /r/ and /l/) of native Japanese speakers. Pillot-Loiseau, Kocjancic Antolik,& Kamiyama[28]concluded that ultrasound biofeedback was effective when teaching native Japanese speakers how to produce French vowels. Georgeton,Antolik, & Fougeron[29]found a correlation between‘prosodic structuring’ and ‘phonetic properties’ of French vowels. Finally, D’Apolito et al.[30]saw an increase in accurate production when using ultrasound technology to improve articulation of American English vowels by Italian speakers. The current study is the first to examine the impact of ultrasound visual biofeedback as an accent modification technique to improve accuracy of American English speech sounds,including vowels and rhotics,produced by native Mandarin speakers.

In contrast to vowel production,the vast majority of studies of ultrasound visual biofeedback have focused on the production of rhotics by individuals with speech sound disorders[31]. As one of many examples, Preston,Leece and Maas[25]examined the use of ultrasound visual biofeedback in the remediation of residual speech sound disorders affecting rhotics. Findings suggested that ultrasound feedback resulted in remediation of rhotic phonemes and caused generalization to sentences.Parallel findings can be found in an increasingly robust literature base and support the use in speech sound disorder intervention and the extension to accent modification services[32].

1.7 Ultrasound and accent modification

More recently, ultrasound visual biofeedback has been implemented to manage accented speech. A one-session pilot study by Gick et al.[33]found the technique useful in teaching three native Japanese linguistic students accurate production of American English phonemes/r/and/l/across positions of CV, CVC or CVCV syllable shapes embedded within a carrier phrase.The 60-minute session consisted of pre and posttraining recordings of the phonemes with the ultrasound with 30 minutes of training when participants compared videos of their productions. After training,‘a(chǎn)ll three participants were able to produce their target approximant successfully’.

Tsui[27]expanded upon the findings of this pilot study by ‘investigat[ing]the effectiveness of using two-dimensional tongue ultrasound to teach pronunciation of[/l/and/r/]to six adult native Japanese speakers’.These phonemes were chosen as dependent variables due to the articulatory and acoustic challenges they present for Japanese speakers. At the end of the study‘a(chǎn)ll participants,who were typical language learners, increased their accuracy of producing English /l/and/r/in a variety of word positions and phonetic contexts’.

1.8 Purpose and hypothesis

The current study aims to facilitate the production of American English vowels and rhotics produced by ELLs who speak Mandarin as their first language.The purpose of this study was to examine the acquisition,generalization, and maintenance effects of ultrasound visual biofeedback training paired with verbal feedback and perceptual training on speech production accuracy based on perceptual ratings from five listeners:

1) Does ultrasound visual biofeedback improve speech sound accuracy of American English phonemes produced by native adult Mandarin speakers when paired with perceptual training and verbal feedback?

2) Does this training result in generalization to untrained items?

3) Do participants maintain accuracy of target production after training is discontinued?

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Design

A single-subject ABAB withdrawal design was employed to determine the effect of ultrasound biofeedback on accent modification across sixteen sessions for two participants. Phase A included four baseline(A1) and four withdrawal (A2) sessions during which no therapy with ultrasound biofeedback or verbal feedback was provided. This sequence was repeated. Participants returned six weeks post-training to assess maintenance of phoneme production.

2.2 Participants

Participant 1 was a 23-year-old woman and participant 2 was a 30-year-old man.Both participants spoke Mandarin as their first language and American English as their second language. They were enrolled in the study following completion of informed consent procedures approved by the Duquesne University Institutional Review Board.Neither participant spoke a third language, however participant 2 spoke an additional Chinese dialect.There was no history of accent modification therapy or hearing, neurological, speech or language deficits.

2.3 Procedures

All procedures were completed at the Duquesne U-niversity Speech-Language-Hearing Clinic. Participants were asked to record the probe items on their own devices and email them for review on two occasions during the withdrawal phase due to absences.Raters were unaware of when these instances occurred.

2.3.1 Screening and diagnostic procedures

Screening and diagnostic procedures occurred during a 90-minute initial session. First, the participants completed a questionnaire related to English experience and exposure following Tsui[27]. Additional details regarding the participants were added including type of English exposed to (i.e. British or American),education level, occupation, and language spoken at home. Both were undergraduate students at Duquesne University. Both were undergraduate students at Duquesne University.Participant 1 was a music major and Participant 2 was a business major.Both were first exposed to the English language at school in China;participant 1 at age 6 and participant 2 at age 11. Both were exposed to British English first and later exposed to American English upon arrival in the United States.Participant 1 was first immersed in an American English-speaking environment (Pennsylvania) one year prior. Participant 2 was immersed in a British English-speaking country(Ghana)four years prior.Participant 1 received instruction in American English pronunciation at school for two years but participant 2 had not.Participant 1 spoke American English in 25%of her daily life whereas participant 2 spoke American English during about 90% of his day. Both spoke Mandarin Chinese while at home and when not speaking American English. Both spoke American English most often in school.Both were very motivated to participate in the study and rated their American English pronunciation as average(5)on a scale of 1-10(10 being excellent).

Similar to Tsui[27], participants passed hearing at 20 dB (using a pure-tone audiometer at 1 000, 2 000 and 4 000 Hz) and vision screenings. Vision screenings were completed on both static and dynamic ultrasound images after initial orientation to determine stimulability.The equipment use was modelled before it was given to the participants. They were asked to identify key points (e.g. ‘top’ border of tongue). Both participants were stimulable.

Findings from the screenings concluded that participants were appropriate candidates. Following Sikorski[34],the Prosody-Voice Screening Profile(PVSP)[35-36]was administered to assess the prosodic characteristics of 24 utterances from a spontaneous speech sample.A single utterance could be coded for more than one characteristic. A total of 24 of 24 (100%) of participant 1’s utterances were coded as inappropriate.Common codes related to stress(67%)and phrasing(38%).Participant 2 had a total of 23 of 24 (96%) utterances coded as inappropriate. Participant 2 exhibited atypical manners of stress(67%),phrasing(46%)and loudness(58%). Errors for both participants were characteristic of Mandarin influence(i.e.different stress patterns, language processing/rewording) and were not explicitly targeted during accent modification sessions.

Similar to Hack,Marinova-Todd,and Bernhardt[37],a standardized articulation assessment (i.e. Photo Articulation Test (PAT)[38]was administered to determine the participants’speech sound skills as related to normative data for their gender and age.When English vocabulary breakdowns occurred, the target word was modelled.Participant 1 obtained a raw score of 19 errors and a standard score of 62.Errors noted and relevant to this study included medial/ε/and final/r/.Participant 2 obtained a raw score of 21 and a standard score of less than 60. Errors included medial /I/, final/r/,/r/blends and medial/ε/.

Following Lam and Tjaden[16]and Fritz and Sikorski[39], a passage reading was administered to determine articulation patterns at the sentence level and percent consonants correct (PCC) per recommendations by Schmidt[19]and Sikorski[34]as well as past use by McAllister Byun and Hitchcock[40]and Morton,Brundage and Hancock[41]. The Caterpillar Passage[42]was selected because of its incorporation of prosodic contrasts and words of varying length and complexity.PCC for participant 1 was 93%.Errors included i I substitution, labialized and distorted /r/across all positions and distorted vowels.Participant 2 had 87%PCC.Errors included i/ε substitution,i I substitution and omitted or distorted /r/ across all positions.

The Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test[43]was administered to determine proficiency in English vocabulary following Morton, Brundage and Hancock[41].Participant 1 obtained a raw score of 102 and standard score of 38. Participant 2 obtained a raw score of 123 and standard score of 48. Target words were selected based on these scores so that no words were misunderstood by the participants.

Following,Behrman[14]and Fritz and Sikorski[39]the Proficiency in Oral English Communication Screening(POEC)[44]was administered due to its high validity for assessing foreign accent as noted by Morton,Brundage and Hancock[41]and recommendation via personal correspondence by Dr.Alison Behrman.Subtests Ⅱ, Ⅲ, Ⅴ and Ⅵ were administered.Participant 1 had 15%falling pitch contour errors,0%rising pitch contour errors and 38% total stress errors during lengthier messages. Participant 1 also had 13% total stress errors during the contrastive intonation subtest.Participant 1 had 13%listening errors and 5%delayed responses during the auditory discrimination subtest.Participant 2 had a total of 46% falling pitch contour errors, 50% (1 out of 2) rising pitch contour errors and 19%total stress errors for lengthier messages.Participant 2 also had 7% total stress errors for contrastive intonation. Participant 2 had 5% listening errors with 10% delayed responses during the auditory discrimination subtest.

2.3.2 Target selection

The three least accurately produced phonemes noted during the PAT[38], spontaneous speech sample,and Caterpillar Passage[42], that were also stimulable for ultrasound procedures (i.e. produced within the oral cavity) were selected. Targets for participant 1 included multisyllabic final /r/ and medial /I/ words.Targets for participant 2 were monosyllabic final /r/and medial /ε/ words for participant 2. Both participants also demonstrated errors with medial /ε/ in 1-3 syllable contexts. A master probe item list was made up of 15 words for each target phoneme and randomly divided into three subsets. Five words were trained (i.e., trained) and probed, five words were probed but not trained to measure for generalization and five words were trained but not probed to minimize testing effects. In total, 10 items were trained and 10 probed during each training session. The third target was not introduced until the first two targets reached 75% accuracy during production.

After 75% accuracy was reached for the initial target phonemes, more complex contexts were introduced for baseline probing to determine continued effects of accent modification procedures and generalization to a more challenging context.The third target,medial /ε/ in 1-3 syllable words, was introduced for baseline measures during final two sessions of Baseline2.In addition,original probe words were placed in the carrier phrase‘say___again’followingChen,Robb,Gilbert and Lerman[8]to determine generalization.Following Adler-Bock,Bernhardt,Gick,and Bacsfalvi[45],probe items were presented randomly each session without clinician models. Probe items were presented in 74-point Times New Roman font in black via PowerPoint on a 2013 13-inch Apple MacBook Pro.Similar to Preston, Brick, and Landi’s[31]seminal work that is emulated in ultrasound biofeedback research for speech production, each probe word was read aloud three times to determine average performance.

2.3.3 Equipment,materials and examiners

An Interson PI 7.5 MHz ultrasound transducer was placed under the mandible at the base of the tongue to transduce sonic waves through a small amount of Aquasonic gel on the probe during production of the phonemes following Preston et al.[32]. The ultrasound was connected to a Dell Latitude laptop with a 13-inch screen using SeeMore software. Participants held the ultrasound probe sitting about 18 inches from the screen during training sessions after initial orientation by the clinician.Audio-recordings were completed using Audacity 2.0 software via a head worn Micro Mic C 520 condenser microphone worn approximately one inch from the participant’s mouth and modulated with a pre-amplifier (PreSonus Audio Box 22VSL). A second-year graduate student administered all screening,diagnostic and training sessions. A speech-language pathology faculty member oversaw all procedures.

2.3.4 Experimental procedures

Experimental procedures paralleled Sjolie, Leece,and Preston[46].As stated previously,there were a total of 4 baseline sessions without training, 4 training sessions, 4 sessions without training (i.e., withdrawal phase),and 4 sessions with training reinstated.

2.3.5 Initial baseline phase(Baseline1)

Instructions regarding how to use the ultrasound were reiterated at the beginning of the initial baseline session. Perceptual training took place during the first five minutes. Probe items were read three times to characterize pre-training accuracy without the ultrasound equipment.No models were given.

2.3.6 Training phase I(Training1)

The participant completed a thirty-minute training session twice per week. Ultrasound training sessions were divided into three time periods and a timer was used to adhere to time allowances. Sessions began with perceptual training (five minutes). Next, training with the ultrasound was administered for twenty minutes in the form of drill-like therapy(i.e.training word read aloud by participant) with verbal cueing (e.g.‘pull your tongue back’). The participants read the entire list of probe items without verbal feedback during the last five minutes.

2.3.6.1 Perceptual training Based on the theories of underlying mechanisms noted by Bernthal, Bankson and Flipsen[47]and Van Riper’s Complexity Staircase Model[48], perceptual training was implemented to correct auditory perception of target phonemes.Participants were asked to identify correct and incorrect productions of ten randomized target phoneme pairs.Spe-cific verbal feedback was given concerning accuracy of perception.No production occurred at this time.

To complete these measures, six individuals who spoke Mandarin as their first language(4 female and 2 male)read 40 words related to the target phonemes(e.g.‘poor’, ‘give’) in a 15-minute session. Words paralleled the complexity and context of targeted phonemes(e.g.monosyllabic medial/I/words).No models were given. Recordings were broken into words and saved as audio files.Only recordings with incorrect or correct productions of the target phoneme were saved to decrease confusion and minimize effect of hearing other incorrect phonemes.

2.3.6.2 Verbal feedback Verbal feedback was based on principles of motor learning described by Maas,Robin,Austermann Hula,Freedman,Wulf,Ballard,et al.[49]. Maas et al.[49]described two types of verbal feedback: knowledge of performance (KP) feedback(i.e. ‘the nature or quality, of the movement pattern’)and knowledge of results(KR)(i.e. ‘information about the movement outcome’).KP feedback was given early in training to enhance understanding and production ofcorrect motor skills(e.g.‘pull your tongue back’)before switching to KR feedback when the movement became learned.

Following Sjolie,Leece and Preston[46],verbal cues were based on the participant’s accuracy of constricting the anterior tongue (e.g., ‘lift the back of your tongue’), lateral elevation of the sides of the tongue(e.g., ‘lift the sides of your tongue’) and incorrect movement(e.g.‘keep the body of your tongue down’).

2.3.7 Withdrawal phase(Baseline2)

Following the first phase of training during which both participants reached over 75% accuracy, ultrasound visual biofeedback was removed for four 30-minute Baseline2 sessions twice a week for two weeks.Original probe items, more challenging probe items,carrier phrases (i.e. stimulus items embedded in a phrase),and the third target,/ε/,were probed.

2.3.8 Training phase Ⅱ(Training2)

Procedures for Training1 were replicated for Training2.Training of the first original set of trained words ceased but were probed to analyze retention.The more challenging probe items and third target were introduced for training. Verbal feedback continued to be implemented with ultrasound biofeedback. Carrier phrases continued to be probed for generalization.

2.3.9 Maintenance session

A one-hour follow-up session was conducted six weeks post training.Initial diagnostic procedures were re-administered. A new list with the target phonemes in varying word lengths and contexts was read three times for generalization. Original probe words were read three times to determine maintenance of speech sound accuracy.

Additional assessment items were re-administered at the time of the maintenance session. Spontaneous speech samples were elicited and assessed with the PVSP[35].Participant 1’s utterances decreased by 42%and Participant 2’s inappropriate utterances decreased by 17%from the diagnostic session.Both continued to exhibit stress and phrasing concerns that were characteristic of Mandarin likely because no explicit instruction of these parameters was provided. Of the errors noted on the PAT, participant 1 only had errors with/r/ blends, while prevocalic /r/, vocalic /r/, /ε/ and /I/were not in error[38].Participant 2 only had errors with/I/. Participant 2 had errors characterized by atypical stress and intonation following administration of the POEC.Participant 1 exhibited a 7%decrease from the diagnostic session and Participant 2 exhibited a 9%decrease from the diagnostic session regarding auditory discrimination errors. During The Caterpillar Passage reading,Participant 1 read with 3%PCC increase from the diagnostic session. Less i I substitutions and/r/distortions were noted.Participant 2 read with a 4%PCC increase.

2.4 Data analysis

2.4.1 Perceptual rating procedures

The data were captured using a video and audio recording system available within the speech and language clinic. Five pre-professional phase speech-language pathology students, who speak American English as their first language and did not have experience with accent modification protocols, served as na?ve listeners and rated accuracy of phoneme production across sessions in random order, similar to Sjolie,Leece and Preston[46].Listeners scored productions as correct or incorrect. Percentage of probes scored correct was averaged and used for the final visual and quantitative analysis. Participants were also asked to score overall accuracy of each probe set as well as carrier phrase productions along a visual analog scale like the CAPE-V[50]following findings from McSweeny&Shriberg[51]and ASHA[52].Carrier phrases were measured to determine generalization of skill. Participants marked an ‘x’ to the closest representation along a 100 mm line (i.e ‘a(chǎn)ccurate’ or ‘not accurate at all’).Higher numbers corresponded with more accurate productions. These data were included to augment visual analysis findings.

2.4.2 Visual analysis

The naive listeners’ perceptual analysis data from each session were plotted on line graphs following procedures outlined by Kratochwill,Hitchcock,Horner,Levin, Odom, Rindskopf and Shadish[53]. Data was examined for changes in level,variability and trend to determine implementation of ultrasound biofeedback and improvement of production accuracy.

2.4.3 Quantitative analysis

Quantitative analyses served as the primary means for determining effect of training and were based on the perceptual dichotomous ratings. Quantitative analyses were modified from studies by McAllister Byun[54]and Behrman[14]and included analyses of data before and after intervention periods. Descriptive analysis of central tendency and variability for all conditions(targeted trained, untrained, total and non-targeted items)were completed. Standard mean difference (SMD) effect sizes and percent non-overlapping data(PND)were completed to deduce similarities in performance across and between phases following Olive and Smith[55].SMD was calculated by finding the difference between the means of the first baseline and second training sessions divided by the standard deviation of the scores in the first baseline phase. That is T2-B1/SD B1. PND was calculated by finding the highest baseline point and the number of intervention points that fell above the highest baseline

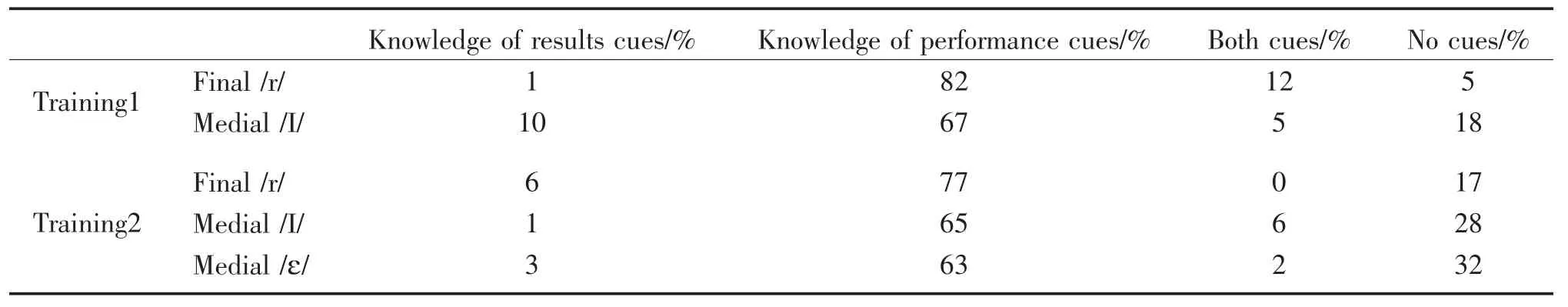

2.4.4 Training fidelity

Similar to Rusiewicz and Rivera[56]and Sjolie,Leece and Preston[46], 25% of training sessions were viewed by an individual unfamiliar with the purpose of the study. Use of KP or KR, verbal cues, number of probes targeted,and implementation of visual biofeedback with the ultrasound (see tables 1 and 2) were monitored and recorded. The individual confirmed that ultrasound was implemented 100% of the time.Ten probes were trained between 7 and 12 times each.The same measures were determined for Training2.Ten probes were trained between 8 and 12 times each.KR verbal feedback was implemented more often than KP feedback.Both cues were implemented more often during Training1.No cues were given most often during Training2. Fidelity measures were replicated for participant 2. Ultrasound was implemented 100% of the time. All probes were trained between 6 and 13 times each during Training1. For medial /?/, technical issues resulted in the recording cutting short during the 8th training word so fidelity could only be recorded for 8 words. All 8 words were trained between 6 and 11 times each. The same measures were determined for Training2. Ten probes of each target were trained up to 13 times each. KR cues were given most often.No cues were given more often during Training2.

Table 1 Participant 1 training fidelity

Table 2 Participant 2 training fidelity

3 Results

3.1 Participant 1

3.1.1 Visual analysis

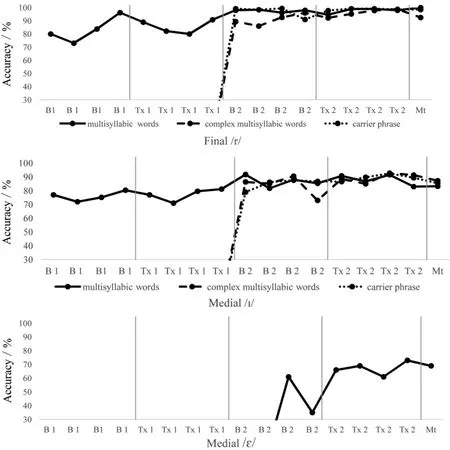

There were several points of evidence of a training effect based on visual analysis of perceptual ratings(see figure 3). First, the average Baseline1 performance of 87% accuracy increased to 99% accuracy during Training2 for all final /r/ productions. The greatest increase for trained productions was from Baseline1 to Training1(i.e. 88% accuracy to 90.74%)and from Baseline1 to Training2(i.e.84.75%accuracy to 98.25% accuracy) for untrained productions. All productions reached at least 98.25% accuracy and maintained the same accuracy or higher during the maintenance session.The average performance during Baseline1 was 77.1% accuracy and 90.2% accuracy during Training2 for the all medial /I/ productions.The greatest change was seen from Baseline1 to Training1(i.e.78%accuracy to 90.75%accuracy)for trained productions.There was less of an increase from Baseline2 to Training2(i.e.89%accuracy to 90.75%accuracy) due to high accuracy being reached during the second baseline phase. For untrained productions, an increase from 83.25% accuracy during Baseline1 to 94.25%accuracy during Training2 was noted with the greatest increase between phases being from Baseline1 to Training1(i.e.83.25%accuracy to 91.25%).For all mean judgements of medial /ε/, an increase from the baseline to training phase was noted (i.e. 55% accuracy to 67.2% accuracy). The average mean accuracy was 67.2%during the training phase.Overall,variability was greatest for all phonemes during initial training and baseline phases. There was a positive trend overall. Level determined overall change between phases for all phonemes. Although baselines were high for medial /I/ (i.e. 77.1% accuracy) and final /r/ (i.e. 87%accuracy),performance was not steady during baseline and Training1 sessions.High accuracy was reached by the second training phase and continued through to maintenance for all targets.

Figure 3 Participant 1 visual analysis

Visual analog scores showed improvement and maintenance by the end of the study and corresponded with dichotomous ratings (see figure 4). There was a smaller variability between scores for participant 1 (i.e., 61%-99.4%). Medial /ε/ showed the least amount of improvement (i.e. initial baseline of 69% accuracy to a maintenance of 69% accuracy). Final /r/ in 2-3 syllable words showed the greatest improvement from an initial baseline of 89.4%accuracy to a final training measure of 98.8% accuracy. Accuracy of production within carrier phrases started relatively high for both targets and maintained accuracy over time. That is, final /r/ productions started with an initial baseline of 99.2% and maintained high accuracy at 98.5% by the maintenance session.Medial/I/began with 79%accuracy and improved to 85.5% accuracy by the maintenance session.

Figure 4 Participant 1 visual analog scores

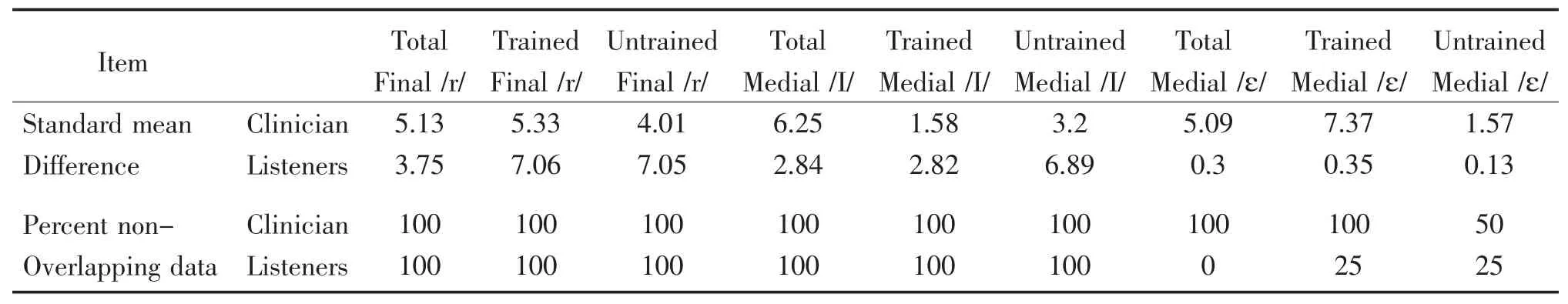

3.1.2 Quantitative analysis

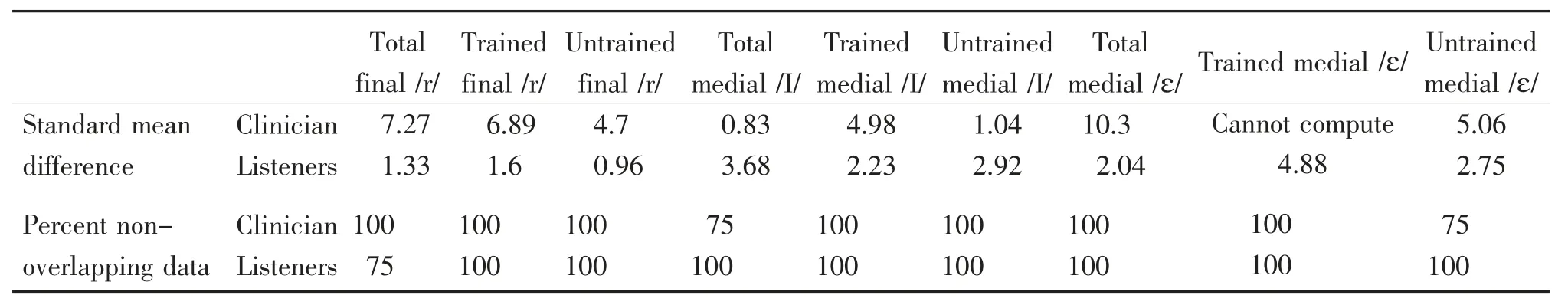

Both SMD and PND measures showed a clinically relevant effect of training(see table 3). SMD relates to the degree of change from the initial baseline phase to the final training phase (i.e. greater number shows a greater degree of change). PND measures the difference of data points between the initial baseline and final training phases (i.e. greater percentage shows a greater degree of change given less overlap of data points).The naive listeners’ratings of medial/I/yielded greater SMD numbers for all production groups(i.e.3.68,2.23,and 2.92)than for all production groups of final/r/(i.e.1.33,1.6,and0.96).The naive listeners’ratings yielded the largest effect sizes for trained medi al /ε/ (i.e. 4.88). The clinician’s SMD for trained medial/ε/could not be computed due to a SD of 0 during Baseline1. PND was judged to be 100% for all naive listener data except total trained and untrained productions of final /r/. Using the guidelines for interpreting effect sizes of single subject design phonological treatment studies described by Gierut,Morrisette,& Dickinson[57], these SMD effect sizes fall within medium(2.35-5.89)and small effect sizes(0.09-2.16).

Table 3 Participant 1 quantitative analysis

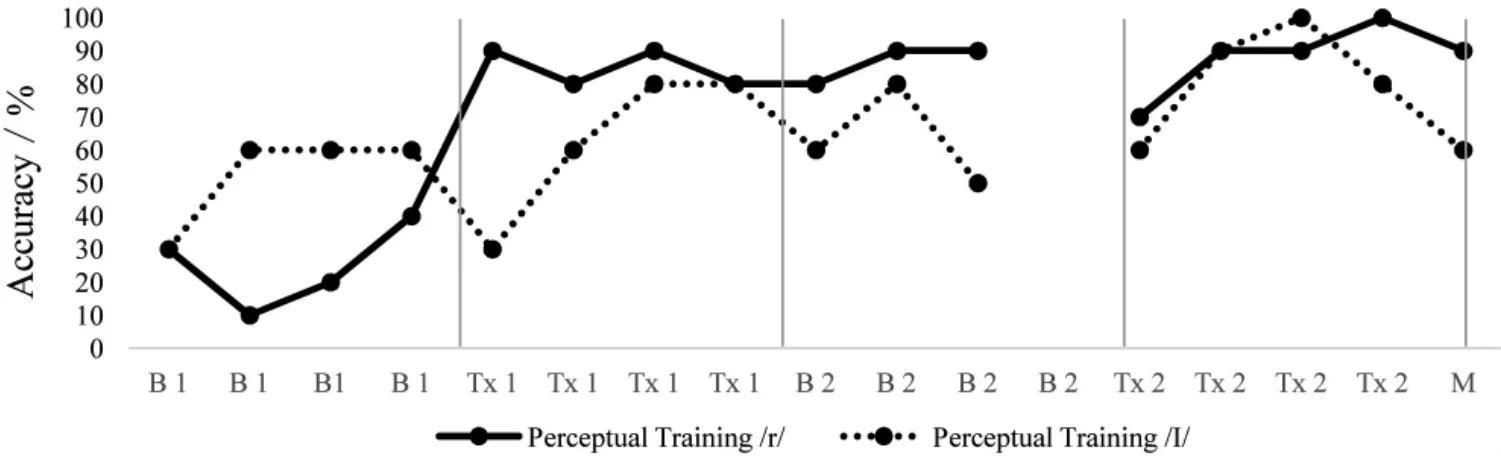

3.1.3 Perceptual training

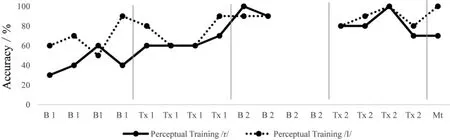

Perception of correct and incorrect production improved as the study progressed. That is, the average performance for medial /r/ during the initial baseline phase was 43% accuracy and increased to 83% accuracy during the final training phase.For medial/I/,the initial baseline yielded an average accuracy of 68%accuracy which improved to an average of 88% accuracy during the final training phase (see figure 5).Slight declination of performance was noted for medial/I/during Training1(i.e.80%to 60%).

Figure 5 Participant 1 perceptual training

3.2 Participant 2

3.2.1 Visual analysis

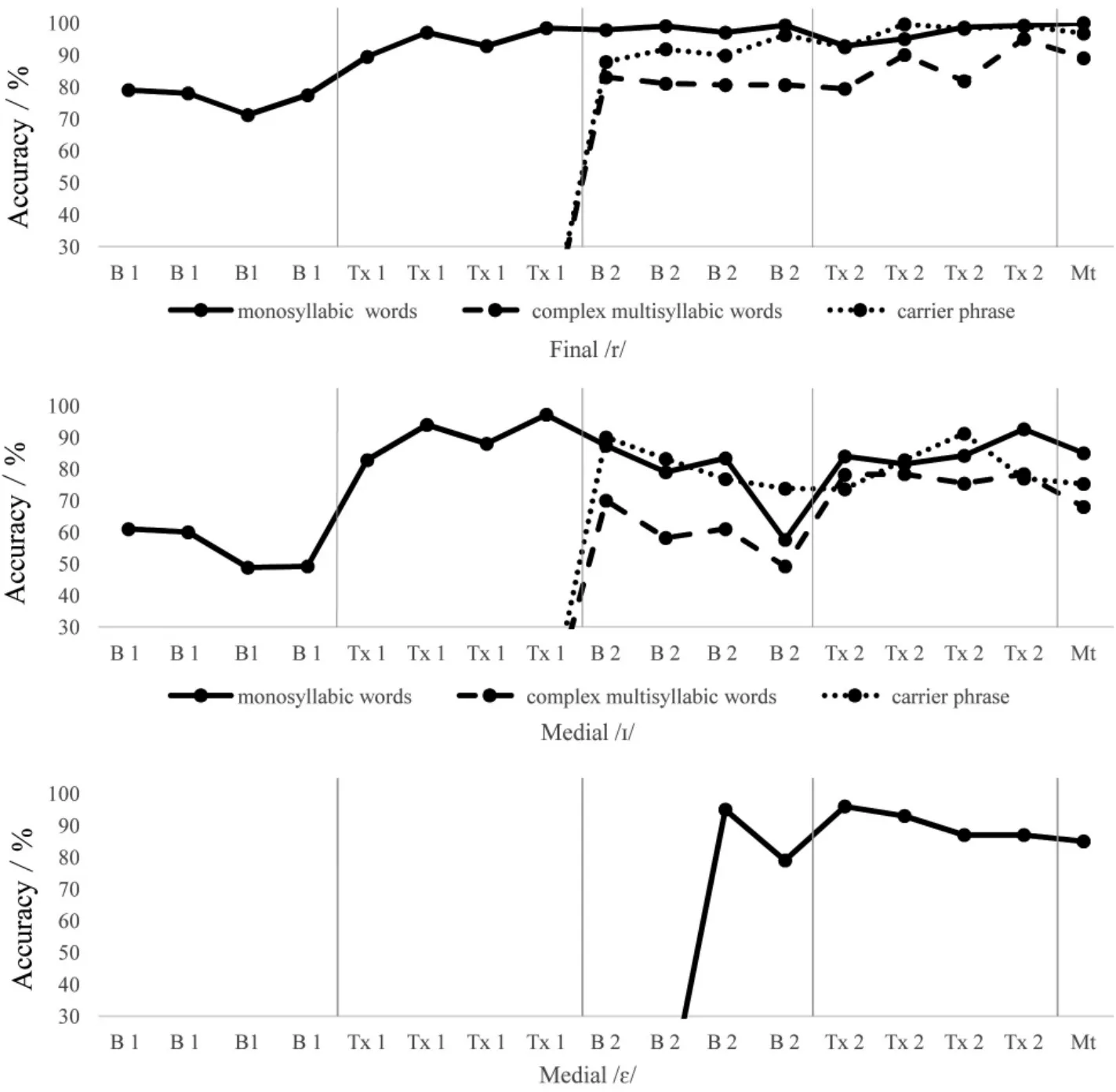

Visual analyses were replicated for participant 2 and again several points evidenced an effect of training. An increase from Baseline1 to Baseline2 (i.e.79.5% accuracy to 99.25% accuracy) and a slight decline from Baseline2 to Training2(i.e.99.25%accuracy to 98%accuracy)was noted for the combined items(trained and untrained)of final/r/productions(see figure 6).Trained items increased from Baseline1 to Baseline2 (i.e. 85% accuracy to 98.5% accuracy), slightly declined from Baseline2 to Training2 (i.e. 98.5% accuracy to 96.5% accuracy) and reached 100% accuracy by the maintenance session. Again, for untrained items, there was an increase from Baseline1 to Baseline2 (i.e. 76.25% accuracy to 99.5% accuracy), no change from Baseline2 to Training2 (i.e. 99.5% accuracy and 99.5% accuracy) and high accuracy posttraining (i.e. 100% accuracy). Although high accuracies were noted during the baseline for final/r/,steady performance was not reached until the final training phase. For the total medial /I/ productions, naive listeners noted an increase from Baseline1 to Training2(i.e. 57.25% accuracy to 81.5% accuracy) (see figure 5).For trained productions,there was an increase from Baseline1 to Baseline2 (i.e. 61.5% accuracy to 89%accuracy) and a slight decrease from Baseline2 to Training2 (i.e. 92% accuracy to 89% accuracy). For the untrained productions, there was a continuous increase from Baseline1 to Training2(i.e.49.75%accuracy to 82.75% accuracy). For all medial /ε/ productions,accuracy improved from baseline(i.e.90.5%accuracy)through training (i.e. 95.25% accuracy). Increases from baseline to training was recorded for almost all groups(i.e.90.5%,97%,and 91%accuracy).There was an initial high accuracy for trained /ε/ productions(i.e.97%accuracy)so less of an increase was noted for this group. Level determined change between phases. Overall, variability was greatest during training phases with high accuracy reached and maintained by Training2 until the maintenance session with a positive trend seen.

Visual analog scores showed a general improvement and maintenance of accuracy by the end of the study and corresponded with dichotomous ratings(see figure 7).Overall scores for participant 2 had a greater variability than those for participant 1 (i.e., 48.8%-100%). Final /r/ in monosyllabic words showed the greatest amount of improvement. Medial /I/ in more complex multisyllabic words showed the least amount of improvement.Generalization to carrier phrases was depicted with relatively high initial numbers which remained somewhat consistent through the end of Training.

3.2.2 Quantitative analysis

Both SMD and PND measures showed a clinically relevant effect of training (see table 4). The highest SMD numbers were noted for both trained and untrained final /r/ ratings (i.e. 7.06 and 7.05), however,all numbers evidenced change. Medial /ε/ showed the least amount of change(i.e.0.3,0.35,and 0.13). PND was judged to be 100% for all total, trained and untrained final /r/ and medial /I/. High PND numbers supported improvement from Baseline1 to Training2 due to training implementation.

3.2.3 Perceptual training

Perceptual training accuracy was recorded across all training and baseline sessions except for one home Baseline2 session(see figure 8).Perception of accuracy improved as the study progressed with slight declines noted for medial/I/during Training1 and Baseline2. That is final /r/ began with an average performance of 25% during the initial baseline phase and improved to an average of 88%accuracy during the final training phase.For medial/I/,the average baseline performance was 53%accuracy which improved to an average of 83% accuracy by the final training phase.The perceptual training data aligns with na?ve listener accuracy ratings.

4 Discussion

This studyof the impact of ultrasound visual biofeedback paired with perceptual training and verbal instructors adds to the limited scholarly work on evidenced-based accent modification interventions. Specifically,these data support the use of ultrasound visual biofeedback as a means to facilitate speech production accuracy of American English rhotics and vowels produced by native Mandarin speakers in a speechlanguage pathology clinical context.

The findings in this study are similar to prior research that examined the role of ultrasound technology for pronunciation training in other languages[2,4-5,28,30].Likewise, this study extends the growing literature on ultrasound visual biofeedback on the training of speech sound targets to the management of accent modification objectives[22,31-32,47,58].Additionally,this study is among very few that explored the use of ultrasound visual biofeedback to improve tongue movements for vowels.The visual analysis and quantitative analysis of naive listeners’ perception of accuracy indicated this training was effective in improving accented speech for both Participants 1 and 2, like previous studies[27,33].Furthermore, data indicated that both participants were able to generalize skill of targets reflecting findings of Preston, Brick, & Landi[31]; Sjolie, Leece, &Preston[46]; and Tsui[27]. Finally, use of visual analog scales augmented visual analyses, noting sensitivity to clinical change[51-52].

Figure 7 Participant 2 visual analog scores

Table 4 Participant 2 quantitative analysis

Figure 8 Participant 2 perceptual training

This training resulted in generalization to untrained targets and more challenging contexts similar to Preston,Brick, &Landi[31]; Sjolie, Leece, & Preston[46];and Tsui[27]. Generalization was crucial to propose this method as a potential training for ELLs. Anecdotally,both participants frequently expressed skills were carrying over and generalizing to everyday speech.This study also sought to determine maintenance of skill, unlike previous studies. Both participants could cue themselves and explain ultrasound imaging by the end of the study. PML were implemented following Preston,McCabe,Rivera-Campos,Whittle,Landry,&Maas[32]as well as Preston, Leece, & Maas[58]. Although KR cues were given most often, the clinician often started Training1 sessions with a longer explanation resembling KP that the participants were very receptive to. Moreover, training focused on ultrasound imaging so less specific feedback was needed during drill-like trials.

In addition to contributing to both established research regarding the effects of ultrasound visual biofeedback on the production of rhotics and the early stages of research on the production of vowels, this study was novel is a number of key ways. First, little empirical evidence is available for accent modification approaches targeting those who speak Mandarin. This was the first study employing ultrasound technology in accent modification services for those who speak Mandarin as their first language. Another unique aspect of this study was the consideration of the underlying mechanisms of accent and incorporating perceptual training following previous studies[19-20,48]Perceptual training improvement paralleled increases in quantitative and visual analyses. Participants perceived their own incorrect productions more accurately by the end of the study. In fact, participant 2 shared that he noticed perceptual differences in fellow ELL classmates’speech as he became more aware of these differences.He occasionally looked away to rely on his perception before looking back at the ultrasound to note tongue change.

As noted previously,the Clear Speech approach has shown benefits of increased intelligibility for both accent modification purposes and otherwise unintelligible speech due to various etiologies[15-17]. Future studies should consider including this approach with ultrasound visual biofeedback to determine whether it can enhance overall intelligibility and improve findings.

There are several limitations that temper the impact of these findings. First, due to the limited sample size of only two speakers, results should be interpreted cautiously due to the high interspeaker variability.While small case studies allow researchers to note key effects of an intervention with scrutiny, such a small size does not allow results to be generalized to greater populations easily.Several studies noted previously also noted the advantages of small case studies when studying the effect of accent modification interventions[25,27,29,33]. Further exploration with larger sample sizes and different populations should be considered for greater efficacy and to be able to generalize results to other English language learners.

In addition, training procedures were drill-like at the word level so results of the participants’ speech outside of the study may not present the same observations.However,participants felt that skills were generalizing. Baselines were not as stable as anticipated. It is possible that probing after training ‘primed’ individuals for more accurate production. However, unprobed targets evidence effect of training. Moreover,the purpose of the study was to examine effect of training after implementation. Participants were also aware of the purpose of the study and had a high motivation to improve production accuracy. Given the underlying mechanism of accent and the implementation of perceptual training, training results may have been due to perceptual training rather than ultrasound biofeedback training. No explicit correlation between the two were examined. Future studies should consider correlating ultrasound image and acoustic analyses with quantitative and visual analyses to improve training protocol.Vowel production with ultrasound biofeedback should continue to be explored to provide more evidence for training of this class of phonemes.Future studies may also consider a multiple baseline design and the effects of learning on performance due to the fact that performance did not completely return to baseline following the removal of Training.

In conclusion,this study suggested ultrasound visual biofeedback as an effective intervention for improving production accuracy of American English phonemes by native Mandarin speakers.This study also points to the need for continued research in the areas of(1)accent modification and (2) ultrasound biofeedback, especially for vowel objectives. Continued research in accent modification would improve SLPs’ ability to meet the communication needs of these individuals.

5 Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to thank the two participants for their dedication to this study. In addition,they would like to acknowledge the six individuals who were recorded for perceptual training methods,the five pre-professional students who rated perceptual analyses and those who completed fidelity and reliability ratings. This investigation would not have been possible without the financial support of the Duquesne University Speech-Language Pathology Department.Finally, they would like to thank Dr. Todhunter and Dr. Lennox of the English as a Second Language Department at Duquesne University for their support.

6 Declaration of interest

There were no conflicts of interest by any of the authors during the completion of this study.The purpose of this study was solely to investigate the hypotheses described.