lnsights into the effects of pulsed antimicrobials on the chicken resistome and microbiota from fecal metagenomes

ZHAO Ruo-nan ,CHEN Si-yuan ,TONG Cui-hong,HAO Jie,Ll Pei-si,XlE Long-fei,XlAO Dan-yu,ZENG Zhen-ling#,XlONG Wen-guang#

1 Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Veterinary Pharmaceutics Development and Safety Evaluation, College of Veterinary Medicine, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou 510642, P.R.China

2 Guangdong Laboratory for Lingnan Modern Agriculture, Guangzhou 510642, P.R.China

3 National Laboratory of Safety Evaluation (Environmental Assessment) of Veterinary Drugs, College of Veterinary Medicine, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou 510642, P.R.China

Abstract Antimicrobial resistance has become a global problem that poses great threats to human health.Antimicrobials are widely used in broiler chicken production and consequently affect their gut microbiota and resistome.To better understand how continuous antimicrobial use in farm animals alters their microbial ecology,we used a metagenomic approach to investigate the effects of pulsed antimicrobial administration on the bacterial community,antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and ARG bacterial hosts in the feces of broiler chickens.Chickens received three 5-day courses of individual or combined antimicrobials,including amoxicillin,chlortetracycline and florfenicol.The florfenicol administration significantly increased the abundance of mcr-1 gene accompanied by floR gene,while amoxicillin significantly increased the abundance of genes encoding the AcrAB-tolC multidrug efflux pump (marA,soxS,sdiA,rob,evgS and phoP).These three antimicrobials all led to an increase in Proteobacteria.The increase in ARG host,Escherichia,was mainly attributed to the β-lactam,chloramphenicol and tetracycline resistance genes harbored by Escherichia under the pulsed antimicrobial treatments.These results indicated that pulsed antimicrobial administration with amoxicillin,chlortetracycline,florfenicol or their combinations significantly increased the abundance of Proteobacteria and enhanced the abundance of particular ARGs.The ARG types were occupied by the multidrug resistance genes and had significant correlations with the total ARGs in the antimicrobial-treated groups.The results of this study provide comprehensive insight into pulsed antimicrobial-mediated alteration of chicken fecal microbiota and resistome.

Keywords: metagenomic,chicken,antimicrobials,resistome,microbial community

1.lntroduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has been highlighted as a global threat by various health organizations,and antibiotic resistant microorganisms lead to enormous financial losses from issues such as substantial morbidity,death,health-care and social costs (Bandyopadhyay and Samanta 2020;Micoliet al.2021).The gut contains an extremely complex and dense microbial community,which is considered a reservoir for antibiotic resistance genes(ARGs) (Kentet al.2020).Enormous quantities of ARGs harbored by animal fecal microbiota can be transported into environmental settingsvialand application (Zhanget al.2019),leakage (Hiltunenet al.2017),and fecal pollution (Karkmanet al.2019).

The world is facing the challenge of how to feed the increasing global population of 9.7 billion in 2050(Modoloet al.2018).Meat production is a priority to offer a protein source that is safe and high-grade for human consumption,and poultry production will be the primary driver of meat production growth from 2020 to 2029 and continue to shift from subsidence agricultural practices to intensive food production including routine antimicrobial usage (OECD and FAO 2020).China is the world’s second largest poultry producer and its consumption is increasing steadily.However,intensive animal production relies on antimicrobials to maintain animal health and productivity.China was reported as the largest consumer of veterinary antimicrobials in 2017,and it is projected to remain the largest consumer in 2030 (Tiseoet al.2020).

Antimicrobial administration leads to profound effects on intestinal microbiota,causing changes in microbial community structure and the fecal resistome (Xionget al.2018).The overuse or misuse of antimicrobials in veterinary practice has undoubtedly promoted the widespread growth of antimicrobial resistance.ARGs can be spreadviamobile genetic elements (MGEs)through conjugation,transduction,and transformation in a process called horizontal gene transfer (HGT) (McInneset al.2020).Amoxicillin,chlortetracycline and florfenicol are widely used antimicrobials in livestock production for treating diseases such as pullorum disease with a treatment period of 3 to 5 days (Agunoset al.2012;Jacob 2015;Elgeddawyet al.2020).We previously investigated the effects of a single-antibiotic administration on the chicken fecal microbiota and resistome after a 5-day course chlortetracycline treatment (Xionget al.2018).Farm animals always receive continuous antimicrobial use for growth promotion or disease treatment.A study of a mouse model mimicking paediatric antimicrobial treatment found that pulsed antimicrobial treatment with a β-lactam or macrolide altered both host and microbiota development (Nobelet al.2015).A broader view of the effects of pulsed antimicrobial treatment on the chicken fecal resistome would help evaluate this risk to the local environment and human health when the poultry manure is discarded into the environment or applied in agricultural production.The effects of a pulsed combinatorial multiple-antibiotic administration on the gut microbiota,resistome and MGEs have not been studied so far.

Here we examined the changes in the antimicrobialinduced fecal bacterial community and ARGs under three 5-day courses of pulsed administration of amoxicillin,chlortetracycline and florfenicol.Using a shotgun sequencing approach,we conducted a comprehensive profiling of the changes in the chicken fecal microbiota,resistome and hosts of ARGs under pulsed antimicrobial treatments.

2.Materials and methods

2.1.Animals,experimental design and sampling

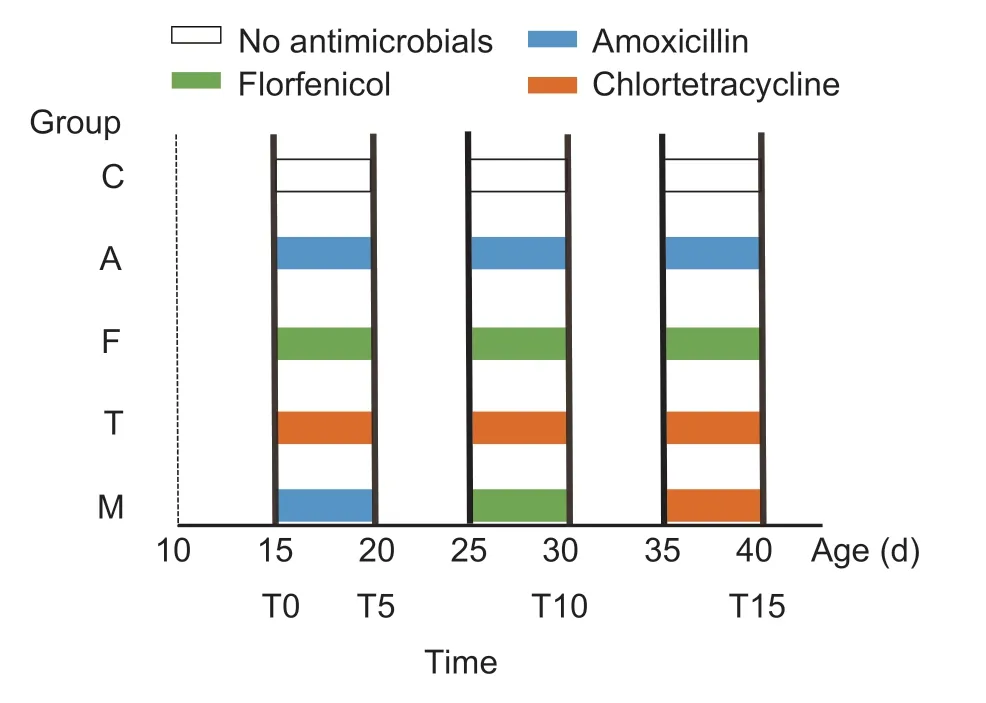

Thirty 10-day-old chickens were purchased in the same batch that had been raised under the standard commercial conditions with no history of antimicrobial treatment(Guangdong Wens Dahuanong Biotechnology Co.,Ltd.,China).The chickens then were transported to the Laboratory Animal Center of South China Agricultural University.The chickens were adapted for 5 days prior to antimicrobial administration.The chickens were separated into five groups with three replicates.Each replicate had two chickens with equal representations of body weight and sex.Each chicken was raised in a cage separately and fed the same supplement of food and water according to the standard commercial cornsoy diet (Yellow Little Chicken Feed,Guangdong Wens Dahuanong Biotechnology Co.,Ltd.,China,and waterad libitum).Each group was kept in a separate room.A control group received no antimicrobials,while the other antimicrobial-treated groups received three 5-day courses of antimicrobials including 0.06 g L–1amoxicillin,0.1 g L–1chlortetracycline,0.06 g L–1florfenicol,and multidrug sequential courses (of 0.06 g L–1amoxicillin,0.1 g L–1chlortetracycline,and 0.06 g L–1florfenicol) at the ages of 15–20,25–30,and 35–40 days (Fig.1).The feces were cleaned every day and they were collected on T0 (before the first treatment),T5 (after the first treatment),T10 (after the second treatment),and T15 (after the third treatment).About 50 g of fresh feces from each cage were individually collected using sterile spoons,placed into sterile tubes and immediately transferred to laboratory for processing.

Fig.1 Animal groups with pulsed antimicrobial administration and sampling time points.The 30 broiler chickens were divided into five groups.Three 5-day courses of antimicrobials were pulse-administered at 0.06 g L–1 amoxicillin (Group A),0.1 g L–1 chlortetracycline (Group T),and 0.06 g L–1 florfenicol (Group F).Group M was treated with all the above antimicrobials sequentially;Group C was set as the control group without antimicrobial administration.Fresh feces from each group were collected on T0 (day 15,before treatment),T5 (day 20,after the first treatment),T10 (day 30,after the second treatment)and T15 (day 40,after the third treatment).Each group had three replicates.

2.2.DNA extraction

To avoid fluctuations,feces from each group were mixed and homogenized.The homogenized fecal samples from each group were divided into three replicates.DNA from each homogenized replicate that contained 0.1 g pretreated feces was extracted using the MoBio PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit following the protocol from the manufacturer (MoBio Laboratories,Carlsbad,CA,USA).Total DNA concentration and purity were determined by UV spectroscopy using a NanoDrop ND-2000 Instrument(NanoDrop Technologies,Wilmington,DE,USA).The DNA samples with OD260/OD280under 1.8–2.0 and a concentration of >50 ng μL–1were subjected to shotgun metagenomic sequencing.

2.3.Metagenomic sequencing

Each fecal DNA sample was sequenced on the Illumina Hiseq 4000 platform using a strategy of Index 150 PE(paired-end sequencing).The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) repository (accession no.PRJNA586747).We removed primers and sequences with ambiguous bases,and filtered low quality reads.

2.4.ldentification of ARG-like ORFs

After quality filtering,the clean reads weredenovoassembled using the CLC Genomics Workbench (version 10.01,Aarhus,Denmark) with the default k-mer size (van de Vossenberget al.2013;Maoet al.2014).Open reading frames (ORFs) within contigs were predicted using Prodigal(Hyattet al.2010).The average coverage was calculated by mapping the metagenomic reads to the ORFs with a minimum length coverage of 95% at 95% similarity of the read length.The protein sequences of the predicted ORFs were searched against the SARG and deepARG databases for the identification of the ARG-like ORFs using BLASTp under anE-value of ≤1010(Arango-Argotyet al.2018;Yinet al.2018).An ORF sequence with the best BLASTp alignment to ARG sequences cutoff of ≥80% similarity and≥70% query coverage was regarded as an ARG-like ORF(Maet al.2016).The relative abundance of a particular ARG was calculated by summarizing the coverages of the ARG-like ORFs belonging to that ARG.The coverage was defined as follows:

whereNis the number of reads mapped to ARG-like ORFs,Lis the target ARG-like ORF sequence length,nis the number of ARG-like ORFs,150 is the length of Illumina sequencing reads,andSis the sequencing data size (Gb) (Maet al.2016).

2.5.Taxonomic classification

The predicted protein sequences of ORFs within the ARG-carrying contigs were annotated against the NCBI NR database using BLASTp at anE-value of ≤10–5.The assignment of taxonomic genus was conducted by annotating the search resultsviaMEGAN6 (Huson and Weber 2013).The assignment of a taxon required the portion of ORFs which were classified into the same taxon to be more than 50% (Ishiiet al.2013).We submitted the sequences of ARGs-carrying contigs to NCBI by using BLASTn and obtained taxonomic information at the genus level.

2.6.ldentification of MGE-like ORFs

The nucleotide sequences of the predicted ORFs were searched against PlasmidFinder for the identification of the plasmid-like ORFs using BLASTn under anE-value of ≤105(Carattoliet al.2014).An ORF sequence with the best BLASTn alignment to plasmid sequences cutoff of≥70% similarity and ≥60% query coverage was regarded as a plasmid-like ORF.The insertion sequence and integron were analyzed using the same approach with the ISFinder and INTEGRALL databases,respectively (Siguieret al.2006;Mouraet al.2009).

2.7.Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons were performed using nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis tests.AP-value of <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

3.Results

3.1.ARG variations

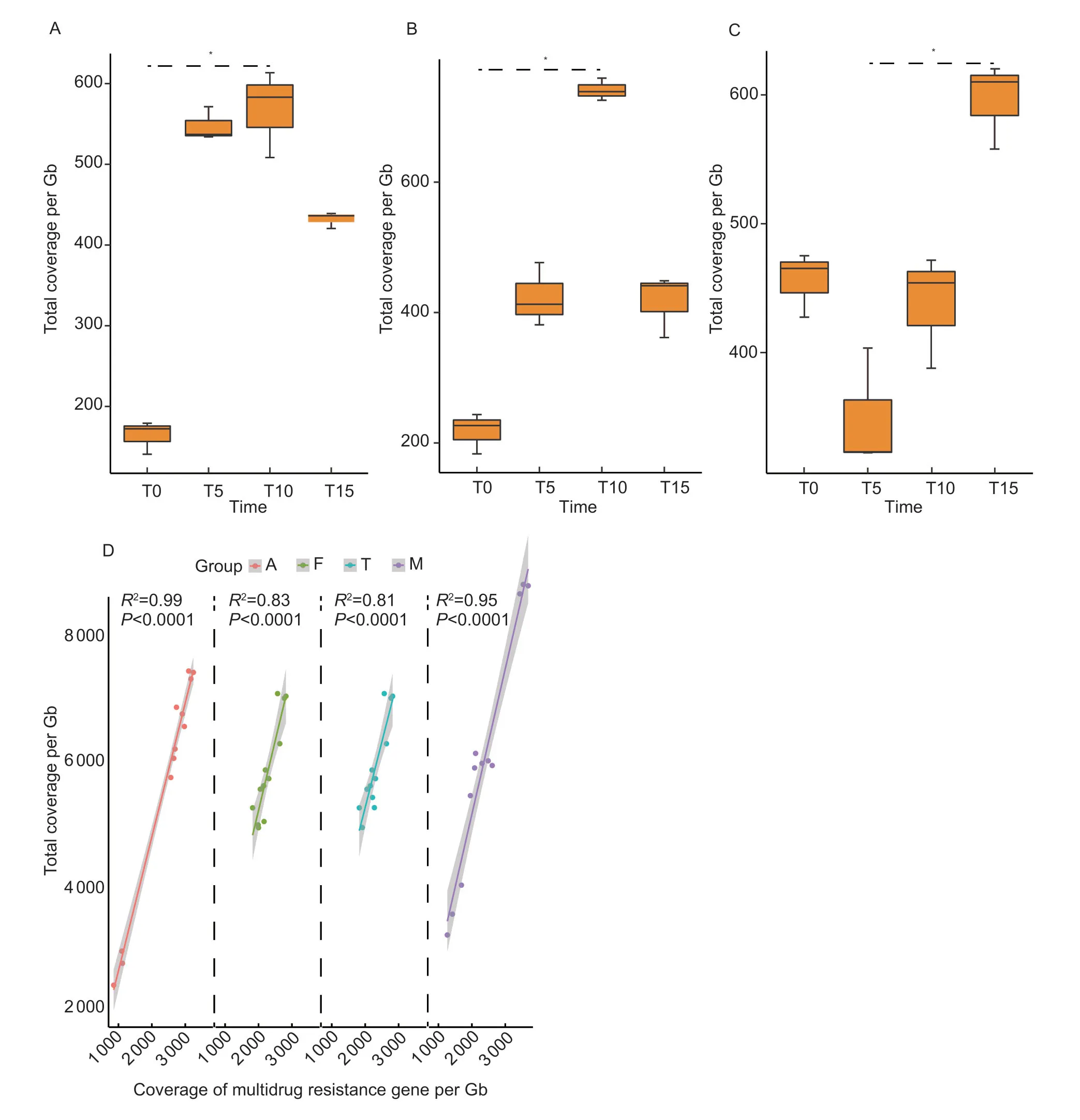

A total of 325 ARG subtypes belonging to 21 ARG types were identified.The resistance genes for multidrug (40%),aminoglycoside (8.9%),polymyxin (7.4%),aminocoumarin(7.4%),and tetracycline (6.9%) were the five predominant ARG types (Appendix A).The detected ARGs represented all major resistance mechanisms,including antimicrobial deactivation,efflux pumps,target alteration,replacement and protection.The total abundance of ARGs found in the control group ranged from 2 506 to 6 224 and the total abundances of ARGs in the amoxicillin,chlortetracycline and mixed groups were significantly higher than the control group (P<0.05) (Appendix A).Polymyxin resistance genes significantly increased on T10 compared with T0 in the amoxicillin and mixed groups (P<0.05).Tetracycline resistance genes significantly increased on T15 compared with T5 in the chlortetracycline group (P<0.05) (Fig.2-A–C).Both florfenicol and chlortetracycline significantly increased the abundance of aminocoumarin resistance genes (P<0.05).Out of these detected ARG types,we found that seven ARG types including bacitracin,β-lactam,fosfomycin,glycopeptide,macrolide-lincosamide streptogramin,streptothricin,and triclosan resistance genes did not show any significant changes under administration of either of the above antimicrobials.We further analyzed the Pearson relationship between the abundance of 21 ARG types and the sum abundance of ARGs in the antimicrobial-treated groups (Appendix B).As the most predominant ARG type in the feces,the abundance of multidrug resistance genes had a high correlation with the sum abundance of ARGs (r2=0.81–0.98,P<0.05) (Fig.2-D).

Fig.2 Changes of antibiotic resistance gene (ARG) types in different samples over the course of pulsed antimicrobials administration.A and B,changes of polymyxin resistance genes over time in Group A and Group M.C,changes of tetracycline resistance genes over time in Group T.D,the correlation between the coverage of multidrug resistance gene with total coverage of ARGs in different groups.Group names were as follows: A,the amoxicillin group;C,the control group;F,the florfenicol group;M,the multidrug group;T,the chlortetracycline group.T0,day 15,before treatment;T5,day 20,after the first treatment;T10,day 30,after the second treatment;T15,day 40,after the third treatment.*,P<0.05.

We also analyzed the ARG variations to quantitatively compare the effects of the antimicrobials on the fecal resistome.The key florfenicol resistance genefloRsignificantly increased on T10 compared with T0 in the florfenicol group (P<0.05) (Fig.3-A).Notably,the colistin resistance genemcr-1occurred at high frequencies and significantly increased on T10 compared with T0 and T5 in the florfenicol group (P<0.05).Themcr-1gene also significantly increased on T15 compared with T0 in the multidrug group (P<0.05) (Fig.3-B).In addition,we studied the genes related to the AcrAB-tolC multidrug efflux pump and found that the regulatory genes of AcrAB-tolC pump,such asmarA,soxS,sdiA,rob,evgSandphoP,showed significant increases in the amoxicillin group (P<0.05) (Fig.3-C).Through Pearson correlation analysis,we found a significant association between the regulatory genes and genes encoding for the AcrAB-tolC pump,includingacrA,acrBandtolC,in the amoxicillin group (r2=0.975–0.995,P<0.05) (Fig.3-D and E).

Fig.3 Variations of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in different samples over the course of pulsed antimicrobial administration.A,the change in the abundance of floR gene in the florfenicol group (Group F).B,the change in the abundance of mcr-1 gene in the multidrug group (Group M).T0,day 15,before treatment;T5,day 20,after the first treatment;T10,day 30,after the second treatment;T15,day 40,after the third treatment.Data are presented as mean±SD of three biological replicates.*,P<0.05;**,P<0.01.C,heatmap of variations in genes relevant to the AcrAB-TolC multidrug efflux pump over time in the amoxicillin group.D,heatmap of Spearman correlations between regulator genes and encoding genes of the AcrAB-TolC multidrug efflux pump.E,complex transcriptional regulatory network of AcrAB-TolC efflux pumps.The activation and verification by our metagenomics data is shown as solid.The repression that our data could not verify is shown by dashes.

3.2.Bacterial community

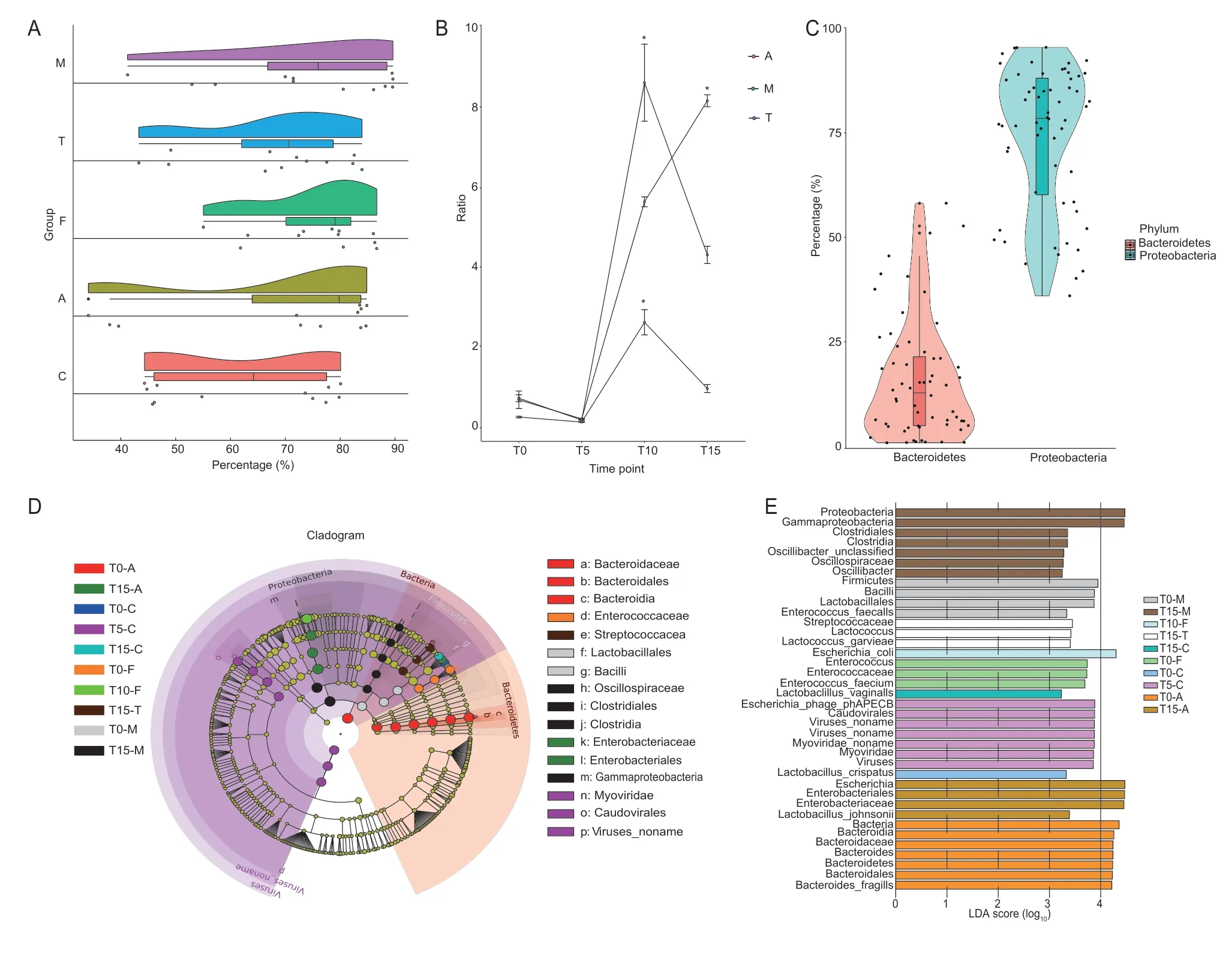

The four predominant taxonomic phyla in the fecal microbiota in broiler chickens were Proteobacteria (70%),Bacteroidetes (15%),Firmicutes (11%) and Actinobacteria(0.030%) in all groups.We found significant compositional shifts of the predominant taxonomic phylum Proteobacteria in these antimicrobial-treated groups after the second antimicrobial administration.In the chlortetracycline group,Proteobacteria significantly increased from 47% on T5 to 83% on T10 compared with the control group (P<0.05);while in the amoxicillin and florfenicol groups,Proteobacteria significantly increased from T0 (37 and 60%,respectively) to T10 (84 and 86%,respectively) compared with the control group (P<0.05).Undoubtedly due to the compound effect,Proteobacteria in the multidrug group significantly increased from 50% on T0 to 90% on T10 (P<0.05) (Fig.4-A).We also analyzed the effect of the different antimicrobial treatments on the fecal Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F:B)ratio.The F:B ratio significantly increased on T10 in the amoxicillin and chlortetracycline groups and on T15 in the multidrug group (Fig.4-B and C).Furthermore,we characterized the differences of fecal microbiota among groups,and the principal component analysis (PCA) plot revealed the different microbial community compositions among the five groups (Appendix C).The predominant taxa Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes were the main responders which was confirmed by the LDA score(LDA>4,P<0.05) and the Linear discriminant analysis Effect Size (LEfSe) analysis identified indicator taxa(Fig.4-C and D).

Fig.4 Changes in bacterial community structure.A,changes in phylum Proteobacteria over time in the different groups.B,changes in the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F:B) ratio over time in the amoxicillin,chlortetracycline and multidrug groups.Data are presented as mean±SD of three biological replicates.*,P<0.05.C,the percentages of Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes.D,cladogram representing the bacterial biomarkers associated with the groups.E,LDA scores of the LEfSe analysis.The cutoff value of linear discriminant analysis is >4.0 and P<0.05.Group names are as follows: A,the amoxicillin group;C,the control group;F,the florfenicol group;M,the multidrug group;T,the chlortetracycline group.For the other group names,for example,T0-A represents before treatment in the amoxicillin group;T5-C represents after the first treatment in the control group;T10-F represents after the second treatment in the florfenicol group;and T15-M represents after the third treatment in the multidrug group.

We further analyzed the microbial communities at the genus level.Escherichia(68%) andBacteroides(15%)were the two predominant genera in all groups.As the predominant genus of Proteobacteria,Escherichiasignificantly increased from T0 (36,56 and 49%,respectively) to T10 (83,85 and 88%,respectively)in the amoxicillin,florfenicol and multidrug groups compared with the control group (P<0.05),while in the chlortetracycline group,Escherichiasignificantly increased from 45% on T5 to 80% on T10 (P<0.05)(Appendix D).The genera that averaged more than 1%relative abundance responded quite differently to the antimicrobials.For example,compared with the control group,Klebsiellasignificantly decreased from 2.7% on T0 to 0.15% on T10 in the florfenicol group (P<0.01);whileKlebsiellasignificantly increased from 0.67% on T0 to 3.7% on T15 in the chlortetracycline group (P<0.05) and significantly increased from 0.42% on T10 to 1.73% on T15 in the amoxicillin group (P<0.01).The distances and variations of this genus on T10 among all the samples were visualized by principal component analysis (PCA),in which PC1 accounted for 59% of the variations between samples (Appendix C).The antimicrobial-treated groups clustered clearly apart from the control group,which represented the differences in the bacterial compositions between the antimicrobial-treated and control groups.

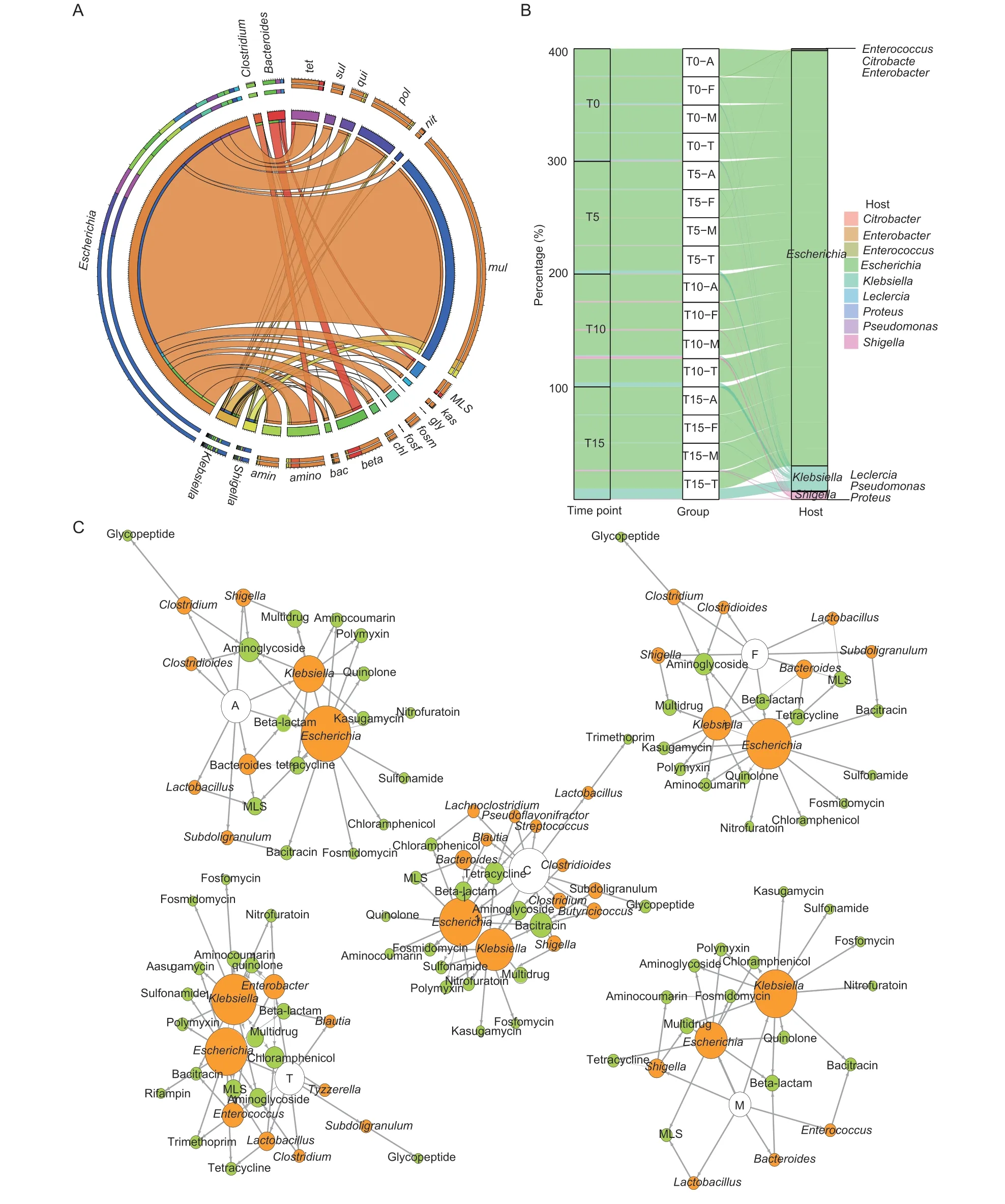

3.3.Bacterial hosts of ARGs

We annotated 10 272 ORFs as ARG-like ORFs that were located in 7 234 contigs (Appendix E).The genera harboring most of the ARGs detected wereEscherichia(84%),followed byKlebsiella(5.1%),Bacteroides(3.9%),Shigella(2.9%),andClostridium(1.7%) (Fig.5-A).EscherichiaandKlebsiellaharbored nearly all of the ARG types (Appendix F).During the experimental period,Escherichiawas always the major host of multidrug resistance genes in all the antimicrobial-treated groups(Fig.5-B).We also found that some less abundant ARGs such as triclosan resistance genes mainly belonged toPseudomonas.

Fig.5 Antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and their bacterial hosts.A,percentages of ARGs hosts.mul,multidrug;tet,tetracycline;amino,aminoglycoside;amin,aminocoumarin;beta,beta-lactam;bac,bacitracin;chl,chloramphenicol;fosf,osfomycin;fosm,fosmidomycin;gly,glycopeptide;kas,kasugamycin;MLS,macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin;nit,nitrofurantoin;pol,polymyxin;qui,quinolone;sul,sulfonamide.B,variations of the multidrug resistance gene hosts over time in the antimicrobial-treated groups.C,changes in the bacterial hosts carrying ARGs from the control group compared with the antimicrobial-treated groups on T10.White,orange,and green nodes mean groups,hosts,and ARGs,respectively.Node size corresponds to amount.Group names are as follows: A,the amoxicillin group;C,the control group;F,the florfenicol group;M,the multidrug group;T,the chlortetracycline group.For the other group names,for example,T0-A represents before treatment in the amoxicillin group,T5-A represents after the first treatment in the amoxicillin group,T10-A represents after the second treatment in the amoxicillin group,and T15-A represents after the third treatment in the amoxicillin group.

We found the changes in ARG-harboring hosts also match the changes in the bacterial community.The major change under the antimicrobial administration occurred at T10.In short,the ARG-harboringEscherichiaincreased on T10 in all the antimicrobial-treated groups,whileBacteroidesdecreased.These results can be explained by the change in the bacterial host of ARGs (Fig.5-C).In the amoxicillin group,the bacterial host of β-lactam resistance genes,Escherichia,increased from 22% on T0 to 77% on T10,and the major host of β-lactam resistance genes changed fromBacteroideson T0 toEscherichiaon T10 when chickens in the multidrug group were fed with amoxicillin.In the chlortetracycline group,the host of tetracycline resistance genes,Escherichia,increased from 6.0% on T5 to 97% on T10.Interestingly,the host of chloramphenicol resistance genes changed fromKlebsiella(100%) on T0 toEscherichia(100%) on T10 in the florfenicol group (Appendix G).

3.4.MGE variations

In this study,we also determined the presence of MGEs,including plasmids,insertion sequences and integrons.In total,there were 89 plasmids detected in all the groups,in which the top 10 plasmids accounted for 51% of the total plasmids.The number of plasmids decreased significantly under antimicrobial administration in the antimicrobial-treated groups (P<0.05) (Appendix H).A total of 173 different integrase genes were found in all the groups,in which 37 different integrase genes with abundance >1% were found.The integrase genes decreased significantly in the amoxicillin and florfenicol groups on T5 compared with T0 (P<0.05) (Appendix I).A total of 367 different insertion sequences were detected in all the groups.The abundances of insertion sequences in the amoxicillin and florfenicol groups significantly decreased on T15 compared with T5 (P<0.05) (Appendix I).We further analyzed the correlation between the total abundances of ARGs and MGEs and found that there was no strong correlation between them under antimicrobial administration (P>0.05).

4.Discussion

In this study,we defined the effects of pulsed antimicrobial treatment on chicken fecal microbiota and resistomes by metagenomic analysis.Highly diverse and abundant ARGs were found in chicken fecal samples.The finding of abundant ARGs in the control group supported the fact that the feces are the reservoir of ARGs,even in the absence of antimicrobial pressure (Sommeret al.2010).The total abundance of ARGs found in the antimicrobial-treated groups was significantly higher than that in the control group,demonstrating that antimicrobials greatly enhanced the abundance of ARGs.Similar results were found in fishes,where the abundance of ARGs was enriched at least 4.5 times under florfenicol exposure (Sáenzet al.2019).We previously reported that the total abundance of ARGs in chicken samples was significantly higher than that in human,ocean,pig and soil samples (Zenget al.2019).The ARGs enriched in our samples were not limited to the antimicrobials administered.Some ARG types,such as the aminoglycoside resistance genes,increased in abundance under the florfenicol and chlortetracycline administration,although they do not confer resistance to the antimicrobials used.Similar results were shown in pigs,where the abundance of aminoglycoside resistance genes increased with in-feed ASP250 which contained chlortetracycline,sulfamethazine,and penicillin (Looftet al.2012).These findings indicate that the particular ARGs may have a specific response to antimicrobial treatment due to co-and/or cross-selection.Our findings supported the theory that antimicrobials have an indirect mechanism of selection conferring resistance to other antimicrobial agents (Hendriksenet al.2019).

Our previous study reported that the effects of the infeed antimicrobials on the fecal resistome were dependent on specific ARGs and not simply overall ARGs (Xionget al.2018).Themcr-1gene,resistant to colistin,which is the last resort antimicrobial for Gram-negative multidrugresistant infections,and was first found in pigs in 2015(Liuet al.2016).We found an increase in the abundance ofmcr-1in the florfenicol and multidrug groups,which indicated that the alternating use of antimicrobials may increase the risk of colistin resistance.The high prevalence ofmcr-1found in chicken feces poses a great risk to the use of colistin in poultry production.Florfenicol resistance can be produced by the genesfloR,fexA,fexB,cfr,cfrlike,poxtAandoptrA(Schwarzet al.2004;Wanget al.2015;Vester 2018).Out of all these genes,onlyfloRwas detected and it showed an increase in the florfenicol group.The synchronous changes in abundance ofmcr-1andfloRin the florfenicol group can be explained by thefloRalways being transferred withmcr-1by IncHI2-F4:A-:B5 plasmid,which leads to the successful flow ofmcr-1under selective pressures (Yiet al.2017).

In our study,the abundance of multidrug resistance genes accounted for the majority of the ARGs abundance,and there was a strong correlation between the abundance of multidrug resistance genes and all ARGs in the antimicrobial-treated groups,highlighting the important role of multidrug resistance genes in ARGs.Our results can be proven by the collateral resistances that can allow for the indirect selection of multidrug-resistant (MDR)bacteria by using single antimicrobial drug (Cantón and Ruiz-Garbajosa 2011).The global spread of MDR pathogens including methicillin-resistantStaphylococcus aureus(MRSA),vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE)and multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria,has raised serious concerns about the infections associated with substantial morbidity and mortality (D’Agata 2018).Therefore,the multidrug resistance genes should receive more attention regarding their competence in AMR.The efflux pump system plays a critical role in the formation of multidrug resistant bacteria (Liet al.2015).The AcrAB-TolC efflux pump is a relevant antibiotic resistance determinant in MDR pathogens (Chetriet al.2019).We found the encoding and regulatory genes of the AcrABTolC efflux pump showed an increase in the amoxicillin and multidrug groups.The high expression of the AcrAB-TolC efflux pump not only induces MDR,but also accelerates the evolution of AMR by mutations in target genes (Schusteret al.2017;El Meouche and Dunlop 2018).Our findings also supported the conclusion that the regulatorsmarA,soxS,sdiA,rob,evgSandphoPcould activate the expression of the AcrAB-TolC efflux pump by a metagenomic approach (Duet al.2018).

A previous study found that children have less stable communities after receiving nine to 15 antimicrobial treatments in the first three years of life compared with the children who never received antimicrobials (Yassouret al.2016).Therefore,tracking the changes in the microbial community is central for estimating the impact induced by antimicrobials (Cuccatoet al.2021).The previous studies which performed research on a single antimicrobial or single administration limited the realization of the effect caused by antimicrobial treatment (Cameron-Veaset al.2015;Aggaet al.2016).In this study,three commonly used antimicrobials were administered continuously for three 5-days courses,constituting a continuous repeated selective pressure,rather than instantaneous disturbance to the microbiota.

Amoxicillin,chlortetracycline and florfenicol are active against both Gram-positive and -negative bacteria,and we found some common and different points in the effects caused by these antimicrobials.On the common side,the antimicrobials significantly affected the Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes compositions under the second antimicrobial treatment.LEfSe analysis further identified these two phyla as the bacterial biomarkers that responded to antimicrobials,indicating that Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes could be the drivers of community dynamics.The F:B ratio is commonly employed as a universal indicator of bacterial community shifts,and these phyla are linked to nutrient consumption and energy harvest from diet (Elokilet al.2020).In our study,the F:B ratio significantly increased in the antimicrobialtreated groups,except the florfenicol group,highlighting the effects induced by amoxicillin and chlortetracycline on increasing the chicken weight.The significant increase in F:B ratio in these antimicrobial-treated groups could be explained by the increase inEscherichiaand decrease inBacteroidesinduced by the antimicrobial administration.However,it should also be noted that the antimicrobials caused different collateral effects on the microbial community.The separated groups in the PCA plots confirmed the differences among the groups and the genera with an abundance of >1% responded quite differently to the antimicrobials.

The previous studies had demonstrated that ARGs depend on the composition of the microbial community which could be an important conduit for transferring ARGs into the environment,suggesting that changes in ARGs are correlated with the structure and composition of the bacterial community (Wanget al.2017;Zhaoet al.2018).In our study,the antimicrobial administration significantly changed the bacterial hosts of ARGs,and then significantly affected the bacterial community composition.Longer samplings in the study may reveal more common long-term responses to antimicrobial therapy.The ARGs can be carried by diverse bacterial hosts with different proportions and the predominant ARGs confer their bacterial hosts with resistance to specific ARG types.Escherichiacarried the most ARGs in all the antimicrobialtreated groups,indicating the antimicrobial effect on this genus is specific to the antimicrobial administered,which was consistent with a previous study that showed an increase inE.coliprevalence in response to oral amoxicillin and chlortetracycline treatments in mammals(Antonopouloset al.2009).Taking the chlortetracycline group as an example,the increase in the proportion ofEscherichiacarrying tetracycline resistance genes allowedEscherichiato survive under continuous chlortetracycline administration.Interestingly,we found that the change in the multidrug group caused by the alternating treatment of the three antimicrobials seems like a combined result of antimicrobial-treated alone groups,suggesting the effect caused by antimicrobials has a cumulative consequence in shaping the ARG-harboring host composition.

Previous studies have demonstrated a significant relationship between ARGs and MGEs in terms of diversity and abundance in different environmental settings (Yuet al.2016;Zhaoet al.2019).However,in our study,there was no positive correlation between the abundance of ARGs and MGE.Furthermore,the abundance of MGEs significantly decreased in the amoxicillin and florfenicol groups.We speculated that pulsed in-feed antimicrobials killed the MGEs-harboring bacteria,leading to the decreased in MGEs in the chicken fecal microbiome.Our study administered continuously for three 5-day courses simulating the practical application in poultry production,so it provided a wider perspective on the influences on fecal microbiota and resistome caused by pulsed in-feed antimicrobials.However,the potential limitations of our study should be considered.We only chose the combination of three antimicrobials,not two antimicrobials for the multidrug group.We used the health chickens to explore the impacts of the pulsed antimicrobials,however,clinically sick chickens most commonly receive antimicrobials in practice.Despite these experimental limitations,understanding the impact of the pulsed antimicrobial administration on the gastrointestinal microbiota and resistome are important for the determination of antimicrobial management strategies.

5.Conclusion

We used a shotgun metagenomic approach to investigate the changes in the chicken fecal microbiome,resistome and bacterial hosts of ARGs in response to pulsed antimicrobial administration.The results showed that the pulsed in-feed antimicrobials all led to significant increases in Proteobacteria.Amoxicillin increased the abundance of multidrug resistance genes,especially the expression of the AcrAB-TolC multidrug efflux pump.Florfenicol could promote the flow ofmcr-1by increasing the abundance offloR.These antimicrobials all increased the proportion of ARGs hostEscherichia,suggesting that antimicrobial alteration of the microbial community is one of the dominant determinants in shaping the broiler fecal resistome.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Laboratory of Lingnan Modern Agriculture Project,China (NT2021006),the Foundation for Innovative Research Groups of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32121004),and the Local Innovative and Research Teams Project of Guangdong Pearl River Talents Program,China (2019BT02N054).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Animal Experimental Ethics Committee of the South China Agricultural University (approval number 2017-B025).

Appendicesassociated with this paper are available on https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jia.2022.11.006

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年6期

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年6期

- Journal of Integrative Agriculture的其它文章

- ldentification of two novel linear epitopes on the p30 protein of African swine fever virus

- Uncertainty aversion and farmers’ innovative seed adoption:Evidence from a field experiment in rural China

- Ensemble learning prediction of soybean yields in China based on meteorological data

- Increasing nitrogen absorption and assimilation ability under mixed NO3– and NH4+ supply is a driver to promote growth of maize seedlings

- Significant reduction of ammonia emissions while increasing crop yields using the 4R nutrient stewardship in an intensive cropping system

- Maize straw application as an interlayer improves organic carbon and total nitrogen concentrations in the soil profile: A four-year experiment in a saline soil