Alternative polyadenylation events in epithelial cells sense endometritis progression in dairy cows

Meagan J.STOTTS ,Yangzi ZHANG ,Shuwen ZHANG ,Jennifer J.MICHAL ,Juan VELEZ ,Bothe HANS ,Martin MAQUIVAR#,Zhihua JIANG#

1 Department of Animal Sciences and Center for Reproductive Biology, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164-7620,USA

2 Aurora Organic Farms, Platteville, CO 80651, USA

Abstract Endometritis (inflammation of the endometrial lining) is one of the most devastating reproductive diseases in dairy cattle,resulting in substantial production loss and causing more than $650 million in lost revenue annually in the USA.We hypothesize that alternative polyadenylation (APA) sites serve as decisive sensors for endometrium health and disease in dairy cows.Endometrial cells collected from 18 cows with purulent vaginal discharge scored 0 to 2 were used for APA profiling with our whole transcriptome termini site sequencing (WTTS-seq) method.Overall,pathogens trigger hosts to use more differentially expressed APA (DE-APA),more intronic DE-APA,more DE-APA sites per gene and more DE-genes associated with inflammation.Host CD59 molecule (CD59),Fc fragment of IgG receptor IIa(FCGR2A),lymphocyte antigen 75 (LY75) and plasminogen (PLG) may serve as initial contacts or combats with pathogens on cell surface,followed by activation of nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group H member 4 (NR1H4) to regulate AXL receptor tyrosine kinase (AXL),FGR proto-oncogene,Src family tyrosine kinase (FGR),HCK protooncogene,Src family tyrosine kinase (HCK) and integrin subunit beta 2 (ITGB2) for anti-inflammation.This study is the first to show significance of cilium pathways in endometrium health and animal reproduction.MIR21 and MIR30A would be perfect antagonistic biomarkers for diagnosis of either inflammation or anti-inflammation.These novel findings will set precedent for future genomic studies to aid the dairy industry develop new strategies to reduce endometritis incidence and improve fertility.

Keywords: organic dairy,endometritis,alternative polyadenylation,infection progression,antagonistic biomarkers

1.Introduction

Postpartum dairy cows face both physiological and pathological challenges.Parturition significantly damages the uterine endometrium,resulting in microbial contamination 80–100% of the time (Pascottiniet al.2015).When inflammation and infection caused by pathogens cannot be controlled by the host immune system,cows consequently develop uterine diseases(Chapwanyaet al.2010).Endometritis generally occurs between 21 and 60 days postpartum.Clinical endometritis (CE) occurs in 20 to 30% of dairy cows while incidences of subclinical endometritis (SE) range from 25 to 33% (LeBlancet al.2002;Sheldonet al.2006;Dubucet al.2011).Conception rates of cows with endometritis are 20% lower than healthy cows (HC).They require up to 10% additional inseminations per conception,leading to increased calving intervals due to more days open and are thus 1.7 times more likely to be culled (LeBlancet al.2002;Sheldonet al.2006;Barlundet al.2008).Economically,endometritis causes dairy farmers to lose approximately $650 million annually in USA due to the treatment costs,decreased milk production,replacement animals,and culling of the failure-to-conceive animals(Sheldonet al.2009).

Research has clearly shown that alternative polyadenylation (APA) events contribute substantially to transcriptome diversity and dynamics,which coordinate genetic information transfers from genome to phenome(Jianget al.2015;Zhouet al.2016,2019;Brutmanet al.2018;Wanget al.2018).Pathogen infection can,however,jeopardize a host’s transcriptome by producing aberrant transcripts.For example,human HeLa-S3 cells infected withSalmonella enterica Typhimuriumexhibited significant differential expression of 142 APA sites within 130 genes (Bonferroni-adjustedP<0.05) (Afonso-Grunz 2015).In chicken embryo fibroblasts challenged with Marek’s disease virus (Liet al.2017),437 genes switched APA sites either within 3′ untranslated regions (3′UTRs)or from 3′UTRs to coding regions.An early study showed that insertion of lentiviral vector into genomic regions of the different human cells triggered use of cryptic polyadenylation signals,producing many aberrant transcripts with but low expression abundancies (Moianiet al.2012).

Bacteria that contaminate the uteri of 90% of cows after calving and may lead to endometritis includeArcanobacteriumpyogenes,Proteus,and Gram-negative bacteria such asEscherichiacoli,Fusobacterium necrophorum,andPrevotellamelaninogenicus(LeBlancet al.2002;Williamset al.2005;Heppelmannet al.2016;Midoet al.2016;Sheldonet al.2018).Bacterial infection in the epithelial layer of the endometrium causes inflammation,histological lesions,and delays uterine involution (Williamset al.2005).Unfortunately,how these pathogens alter APA profiles and whether these alterations are responsible for endometritis remains largely unknown in dairy cows.Therefore,the objective of present study is to discover distinct alternative polyadenylation patterns associated with endometrium repair in healthy cows and endometrium inflammation in unhealthy cows using our whole transcriptome termini site sequencing (WTTS-seq)method (Zhouet al.2016).We believe that such a study will provide novel knowledge about endometritis,novel technology for its diagnosis and novel strategies for its treatment and cure.

2.Materials and methods

2.1.Animals and diagnosis of endometritis

Forty multiparous lactating Holstein dairy cows from a certified organic dairy farm in Colorado,USA were initially screened.All cows examined were free of mastitis and metabolic disorders.Cows were housed in free stall barns with open access to a dry lot and milked three times a day at approximately 8-h intervals.Cows were fed twice daily a total mixed ration formulated to meet dietary nutritional requirements for lactating dairy cows (NRC 2001).Cows had access to pasture between feedings.

The first gynecological exam was conducted on cows that were between (25±5) and (45±5) days post-calving.Endometritis was diagnosed based on presence of purulent vaginal discharge (PVD),which was scored using the gloved hand technique (Williamset al.2005;Barlundet al.2008;Maquivaret al.2015).The uterus was massagedviatrans-rectal palpation,and the perineal area and vulva were cleaned with a paper towel.A lubricated gloved hand was introduced through the vulva into the vaginal vault near the cervical os where vaginal mucus was manually withdrawn.Mucus was scored as: 0,clear uterine discharge;1,flakes of purulent exudate in the uterine discharge;2,>50% of the uterine discharge contained purulent exudate;and 3,hemorrhagic uterine discharge mixed with purulent exudate (adapted from Williamset al.2005;Sheldonet al.2006).Cows with vaginal mucus scores between 1 and 3 were considered to have PVD,an indication of clinical endometritis.

2.2.Endometrial cell collection and RNA extraction

Endometrial cells were collected with modified equine uterine culture swabs (Continental Plastic Corp.,Delavan,WI,USA) from cows with vaginal mucus scores of 0 to 2.Briefly,the outer and swab sheaths of the uterine swab were shortened and the cotton swab on the inner swab holder was replaced with a cytobrush (CooperSurgical,Inc.,Trumbull,CT,USA) treated with ELIMINase(Decon Labs,Inc.,King of Prussia,PA,USA) to remove RNase contamination.The vulva was cleaned and the rod inserted into the uterus where the cytobrush was exposed and cells collected by rotating the swab against the uterine wall.The cytobrush was removed from the sheath and immediately placed into 500 mL of RNAlater(Ambion,Foster City,CA,USA) to stabilize and preserve RNA,incubated in RNAlater at 4°C for 24 h,and stored at–20°C until RNA was extracted.

The cytobrushes were translocated to 2-mL microcentrifuge tubes containing 1 mL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and centrifuged at 18 000×g at 4°C for 10 min.Endometrial cells were collected after scraping the cytobrush against the wall of the tube and centrifuging at 21 130×g at 4°C for 10 min.The supernatant was discarded,350 mL of Trizol (Invitrogen,Carlsbad,CA,USA) were added,and cells were lysed with a micro-vial pestle (Wilmad-LabGlass,Vineland,NJ,USA) for 5 to 7 s.The homogenate was translocated into a new 1.7-mL microcentrifuge tube and an additional 350 mL Trizol added.Thereafter,RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Chomczynski 1993).The TURBO DNA-Free Kit (Invitrogen,Carlsbad,CA,USA) was used to eliminate DNA contamination and RNA was further purified with the RNA Clean &Concentrator Kit (Zymo Research,Irvine,CA,USA).RNA concentrations were determined with a NanoDrop 1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific,Wilmington,DE,USA) and quality assessed with a fragment analyzer(Advanced Analytical Technologies,Inc.,Ankeny,IA,USA).

2.3.Library preparation

Libraries were prepared from total RNA according to the WTTS-seq protocol (Zhouet al.2016).Briefly,at least 2.5 μg of total RNA was fragmented using RNA fragmentation buffer (Ambion,Foster City,CA,USA) and poly(A)+RNA enriched with Dynabeads oligo(dT)25magnetic beads(Ambion,Foster City,CA,USA).First-strand cDNA was synthesized using Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase(Invitrogen,Carlsbad,CA,USA) and both 5′ and 3′ oligos that fit the Ion Torrent platform (Thermo Fisher,Waltham,MA,USA).Next,RNasesH and I (Thermo Scientific,Wilmington,DE,USA) were used to remove all RNA molecules.The single-stranded cDNA was purified using a spin column (Zymo Research,Irvine,CA,USA) and the second cDNA strand synthesized by asymmetric PCR amplification.Double-sided selection with Agencourt AMPure XP solid phase reversible immobilization beads(Beckman Coulter,Indianapolis,IN,USA) using 0.5×beads for the first selection and 0.8× beads for the second selection,was employed to isolate double-stranded cDNA fragments between 200 and 500 nucleotides.Highquality libraries were subsequently sequenced with an Ion PGM? System (Life Technologies,Waltham,MA,USA)at the Washington State University Genomics Core (USA).

2.4.Quality control,mapping and processing

A total of 18 libraries derived from 11 unhealthy cows(with subjective vaginal mucus scores 1 or 2) and 7 healthy cows were analyzed (Table 1).FASTX Toolkit version 0.0.13.1 was used for quality control of all sequenced samples.Per WTTS-seq strand specificities,all thymine(s) (Ts) were trimmed from the beginning of each read using Perl script that kept reads that were≥16 bp for mapping (Zhouet al.2016).The bovine reference genome (Bostaurusassembly ARS-UCD1.2)in FASTA format and annotation file in GFF format was downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome?term=bos%20taurus).Read mapping was performed with TMAP version 3.4.1 (https://github.com/iontorrent/TMAP).Mapped read clusters on the same strand within a 24-nucleotide window were considered APA sites (Zhouet al.2016,2019).

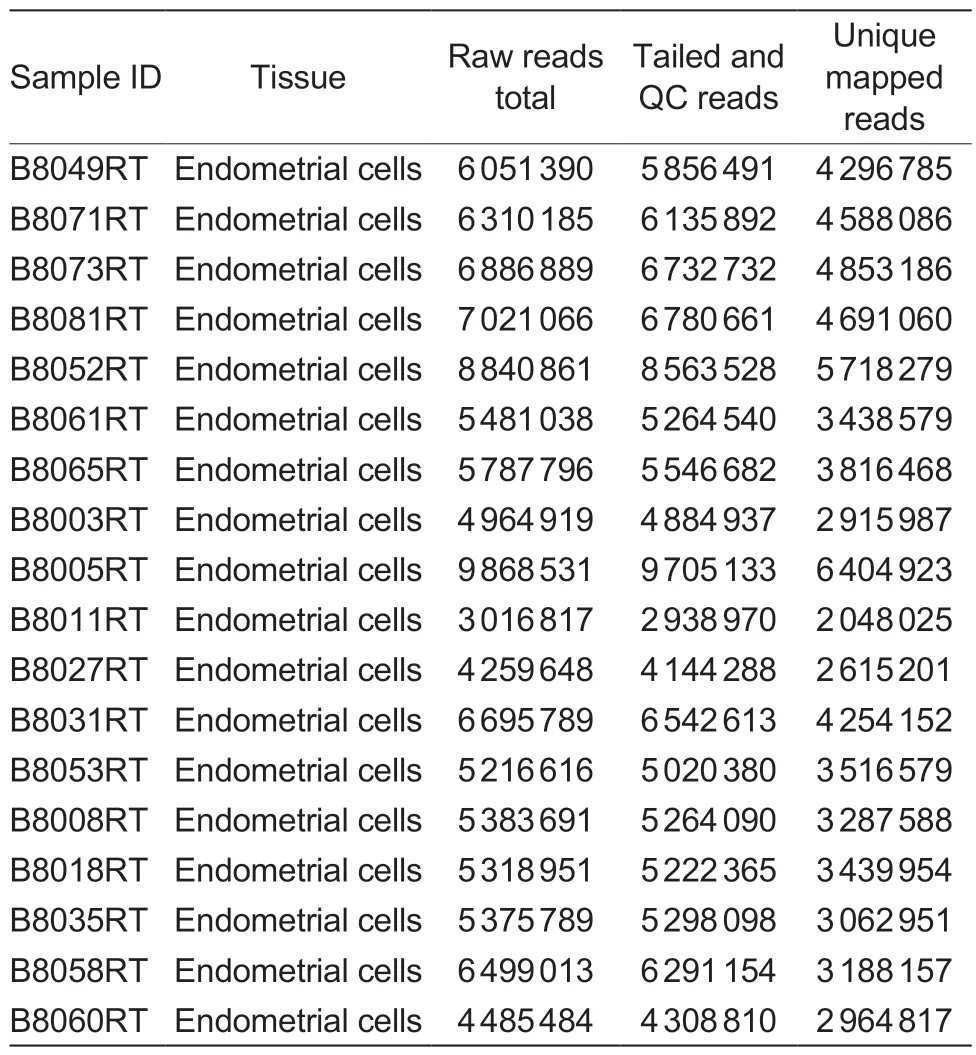

Table 1 Animals,tissue source and WTTS-seq library basics

2.5.Characterization of APA sites

The Cuffcompare tool version 2.2.1 was utilized to assign each APA site to chromosome and consequently to a given gene.Chromosome information included the scaffold number,strand direction,and 5′ and 3′end coordinates.Gene information collected included ID number,strand,biotype,symbol,and transcript ID.The APA sites were assigned gene biotypes,including protein-coding genes,long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs),microRNAs (miRNAs),pseudogenes and small RNA genes.The APA site types included exonic (confined in exonic regions),extended exonic (extended from exonic regions to intronic regions with at least 10 bp),intronic (completed in the intronic regions),distal (exonic regions with extension),extended distal (located within 2-kb downstream of reference transcripts) and antisense(exonic regions,but with opposite direction).Genomic regions of APA sites were characterized into two types:(1) adenosine rich sites (ARSs) and (2) non-adenosine rich sites (NARSs).An ARSs region contained at least 7 consecutive As or a total of 8 As within a 10-bp window downstream of the poly(A) site (Zhouet al.2019).

2.6.Data analysis and statistics

The DESeq2 package in R (Loveet al.2014) was utilized to normalize raw reads among all samples,separate transcriptome profiles between healthy and clinically unhealthy animals,and identify DE-APA sites using aP-adjusted value<0.01.All protein coding genes associated with DE-APA sites were input into Metascape(http://metascape.org/gp/index.html#/main/step1) to create enrichment heat maps using “GO Biological Processes”(Tripathiet al.2015).The STRING database (https://stringdb.org;Szklarczyket al.2017) was used to create protein–protein interaction networks.Networks were visualized using Cytoscape Graphical Network Software version 3.5.1(Shannonet al.2003).At-test was performed to determine differences in number of APA sites in cows diagnosed with endometritis compared to clinically healthy cows.

3.Results

3.1.Characterization of APA sites in dairy cows

A total of 18 libraries yielded 88 798 APA sites that were expressed in endometrial epithelial cells using 36 reads per site as a cutoff (Appendix A).Of those,58 064 were assigned to currently annotated genes in the bovine genome.We observed that gene biotypes had significant effects on use of APA sites per gene (χ2=1210.1,df=36,P<2.2e–16).For example,65% (9 686/14 840) of protein coding genes,40% (577/1 456) of lncRNA,18% (144/804)of pseudogenes,16% (4/25) of miRNAs and 0% (0/24)of transfer RNAs (tRNAs) utilized more than one poly(A)site (Fig.1-A).As such,the average number of APA sites per gene was 3.64,1.90,1.26,1.16 and 1.00 for protein coding,lncRNAs,pseudogenes,miRNAs and tRNAs,respectively (Fig.1-A).

Fig.1 Characterization of alternative polyadenylation(APA) events in dairy cows.A,effects of gene biotypes on number of APA sites per gene.B,usages of class codes.C,mapping regions between adenosine rich sites (ARSs) and non-adenosine rich sites (NARSs).D,transcriptome distances among 18 cows illustrated in with two ways of classification.

Our results showed that 53% of protein-coding genes and 59% of lncRNA had APA sites located within intron regions (Fig.1-B).However,extended distal APA sites were dominant for both tRNAs (77%) and miRNAs (100%)(Fig.1-B).The APA sites associated with pseudogenes involved 28% exonic,28% distal,15% extended distal,1%extended exonic,22% intronic,and 6% antisense (Fig.1-B).The distributions of site-types among these five gene biotypes were significant (χ2=900.88,df=4,P<2.2e–16).

As shown in Fig.1-C,the distribution of NARSs and ARSs are most similar between protein coding genes (73%NARSs,27% ARSs) and lncRNA (78% NARSs,22%ARSs).Pseudogene and miRNA APA classification are more evenly distributed,54% NARSs and 46% ARS in the former,and 62% NARSs and 38% ARS in the latter group.Those within tRNAs were mostly found to be NARs,88%.The ratio of NARs to ARSs was significantly different among five gene biotypes (χ2=230.47,df=4,P<2.2e–16).

The transcriptome distances among these 18 cows are illustrated in Fig.1-D according to the principal component analysis (PCA).Interestingly enough,the relationship patterns allowed us to classify them into different groups based on either subjective scores or transcriptome clusters.For the former classification systems,cows were divided into one of two groups: 1) cows diagnosed as healthy (score 0;n=7 cows);and 2) cows diagnosed as unhealthy (score either 1 or 2;n=11 cows).For the latter classification systems,these healthy cows were further split into: 1) clinically healthy (CH,original score 0;n=4 cows);and 2) conditionally healthy (CoH,cows that had a PVD score of 0 after recovery;n=3 cows),while the unhealthy cows were separated into: 1) clinically mild endometritis (CME;n=6 cows);and 2) clinically severe endometritis (CSE;n=5 cows) based on the transcriptome clustering patterns.

3.2.Dysregulated APA sites in unhealthy cows in comparison to healthy cows

DESeq2 analysis revealed a total of 10 349 DE-APA sites,including 1 547 and 8 802 that were up-regulated in endometrial epithelial cells of healthy and unhealthy cows(adjustedP<0.01,log2(fold change)>|2|),respectively(Appendix B).Among them,52,3,891 and 11 were assigned to lncRNA,miRNAs,protein coding and pseudogenes in healthy cows,and 348,4,5 099 and 50 were DE-APA sites in endometrial epithelial cells from unhealthy cows,respectively.The remaining DE-APA sites were either largely unannotated (588 for healthy and 3 268 for unhealthy) or categorically rare (2 for healthy and 33 for unhealthy).

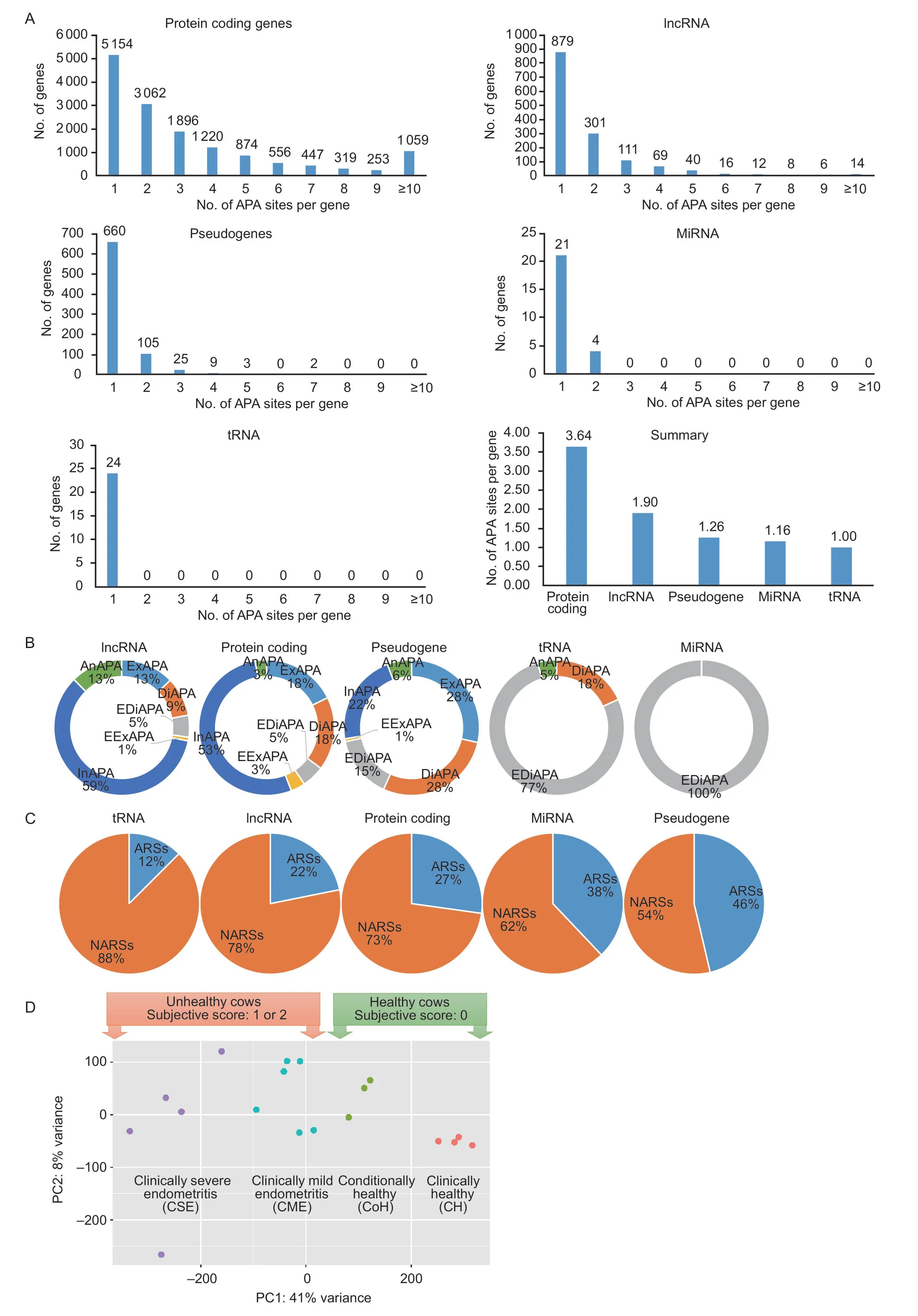

We observed that DE-APA sites in gene biotypes were similar between healthy and unhealthy cows(χ2=9.538,df=9,P=0.3892).However,site type usage was significantly different (χ2=456.68,df=14,P<2.2e–16;Fig.2-A).For instance,intronic APA sites increased from 51% in healthy cows to 66% in unhealthy cows,while distal APA sites decreased 21% in healthy cows to 9% in unhealthy cows.The DE-APA sites adjacent to ARSs also increased significantly from 20% in healthy cows to 26% in unhealthy cows (χ2=52.513,df=2,P=3.954e–12;Fig.2-B).

Fig.2 Characterization of differentially expressed alternative polyadenylation (DE-APA) sites expressed in endometrial epithelial cells between heathy and unhealthy cows.A,healthy cows tended to use less intronic,but more distal DE-APA sites than unhealthy cows.B,unhealthy cows tended to use more DE-APA sites adjacent to non-adenosine rich sites (NARSs) than healthy cows.C,top 20 “summary” pathways enriched with DE-APA sites associated differentially expressed genes (DEGs) up-regulated in healthy cows alone and in unhealthy cows alone.D,the joint enrichment of top 20 “summary” pathways between healthy and unhealthy cows.

Pathway enrichment analysis with Metascape revealed 679 and 2 343 differentially expressed genes associated with the DE-APA sites from healthy and unhealthy cows,respectively (Appendix C).As illustrated in Fig.2-C,the DE genes in endometrial epithelial cells from healthy cows were enriched for pathways related to cilium functions,such as cilium organization,cilium-dependent cell motility,non-motile cilium assembly,cell part morphogenesis,axonemal central apparatus assembly and intraciliary transport.The remaining pathways were relevant to growth,development,regeneration,metabolism and maintenance.

In contrast,the enriched pathways associated with DE genes of cells from unhealthy cows were heavily involved in inflammation.Basically,pathogens triggered the host to:1) respond to inflammation,wounding,lipopolysaccharide,nitrogen compound and lipid;2) activate immune systems and cells;such as cytokine production,myeloid leukocyte activation,lymphocyte activation and neutrophil migration;3) enhance cell activities in chemotaxis,hydrolase activity,cell migration,and endocytosis;and 4) upregulate pathways for cytokine-mediated signaling,small GTPase mediated signal transduction,transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase signaling,peptidyl-tyrosine modification and immune response-regulating signaling(Fig.2-C).

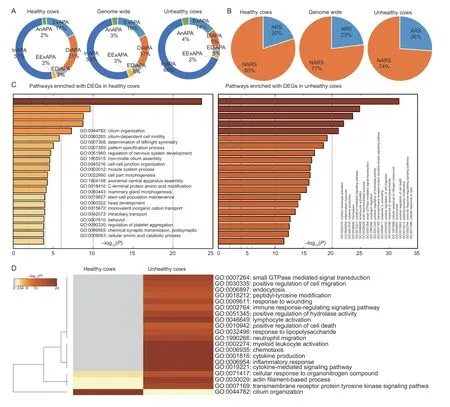

A joint analysis using both sets of DE genes from healthy and unhealthy cows further confirmed the pathways described above (Fig.2-D).Among the top 20“summary” pathways,16 were abundantly enriched in endometrial epithelial cells derived from unhealthy cows.The remaining pathways included three that were enriched dominantly in unhealthy cows and one only dominantly in healthy cows.Although these four pathways were shared between healthy and unhealthy cows,their contributing DE genes were quite different.As shown in Fig.3-A,the common DE genes only accounted for 12–17% (Appendix C).Certainly,these common DE genes executed different APAs that were up-regulated in either healthy or unhealthy cows.Two DE genes: protein kinase C theta (PRKCQ) and protein kinase cGMP-dependent 1 (PRKG1) were used as examples to demonstrate the antagonistic DE-APA sites within each,plus their expression abundances (Fig.3-B).At the protein level,only the cilium organization pathway showed the tendency of separation in protein–protein interaction networks between healthy and unhealthy cows(Fig.3-C).No such trend was seen for the other three pathways (data not shown).

Fig.3 Characterization of shared pathways in endometrial endothelial cells between healthy and unhealthy cows.A,four pathways were enriched for both healthy and unhealthy cows (see Fig.2-D).However,only 12 to 17% of genes were common between them.B,PRKCQ and PRKG1 were used as examples to demonstrate the existence of antagonistic differentially expressed alternative polyadenylation (DE-APA) sites between healthy and unhealthy cows.Ultimately,one DE-APA was up-regulated in healthy cows,while another in unhealthy cows.The significance level was adjusted P<0.05 with log2(fold change)≥|2|.Data are mean and SE with n=7 for healthy and n=11 for unhealthy cows.C,healthy and unhealthy cows tended to have separated protein–protein interaction networks of cilium organization.

Overall,these 20 “summary” pathways involved a total of 1 080 DE genes with at least 289 genes relevant to cytokines,cytokine-associated proteins or cytokine–cytokine receptor interactions (Appendix C).For example,11 interleukin genes (IL1A,IL1B,IL9,IL10,IL12B,IL17A,IL17F,IL21R,IL23A,IL27andIL36A);13 interleukin receptor genes (IL1R1,IL1RL1,IL1R2,IL2RA,IL2RG,IL3RA,IL10RA,IL10RB,IL13RA1,IL17RD,IL17REL,IL18R1andIL31RA);2 interleukin receptor accessory protein genes (IL1RAPandIL18RAP) and 1 interleukin receptor antagonist gene (IL1RN) appeared on the list of DE genes (Appendix C).

3.3.APA sites as molecular sensors for endometritis progression in dairy cows

The endometritis progression events were dissected by comparing CH with CoH,CME and CSE groups of cows.Because CH served as a reference three times,we named them CH1,CH2 and CH3,respectively.When adjustedP<0.01,log2(fold change)>|2| was employed,598 and 467;1 751 and 4 475;and 3 992 and 13 308 DEAPA sites were up-regulated for the CH1–CoH pair,CH2–CME pair and CH3–CSE pair,respectively.To balance the numbers of DE genes for pathway enrichment,we used different cut-offs for CME (3 868 DE-APA sites,P<0.01,log2(fold change)>|3|);CH3 (3 164 DE-APA sites,P<0.005,log2(fold change)>|2|) and CSE (10 556 DE-APA sites,P<0.005,log2(fold change)>|3|) (Appendix B).No changes were made for other groups.

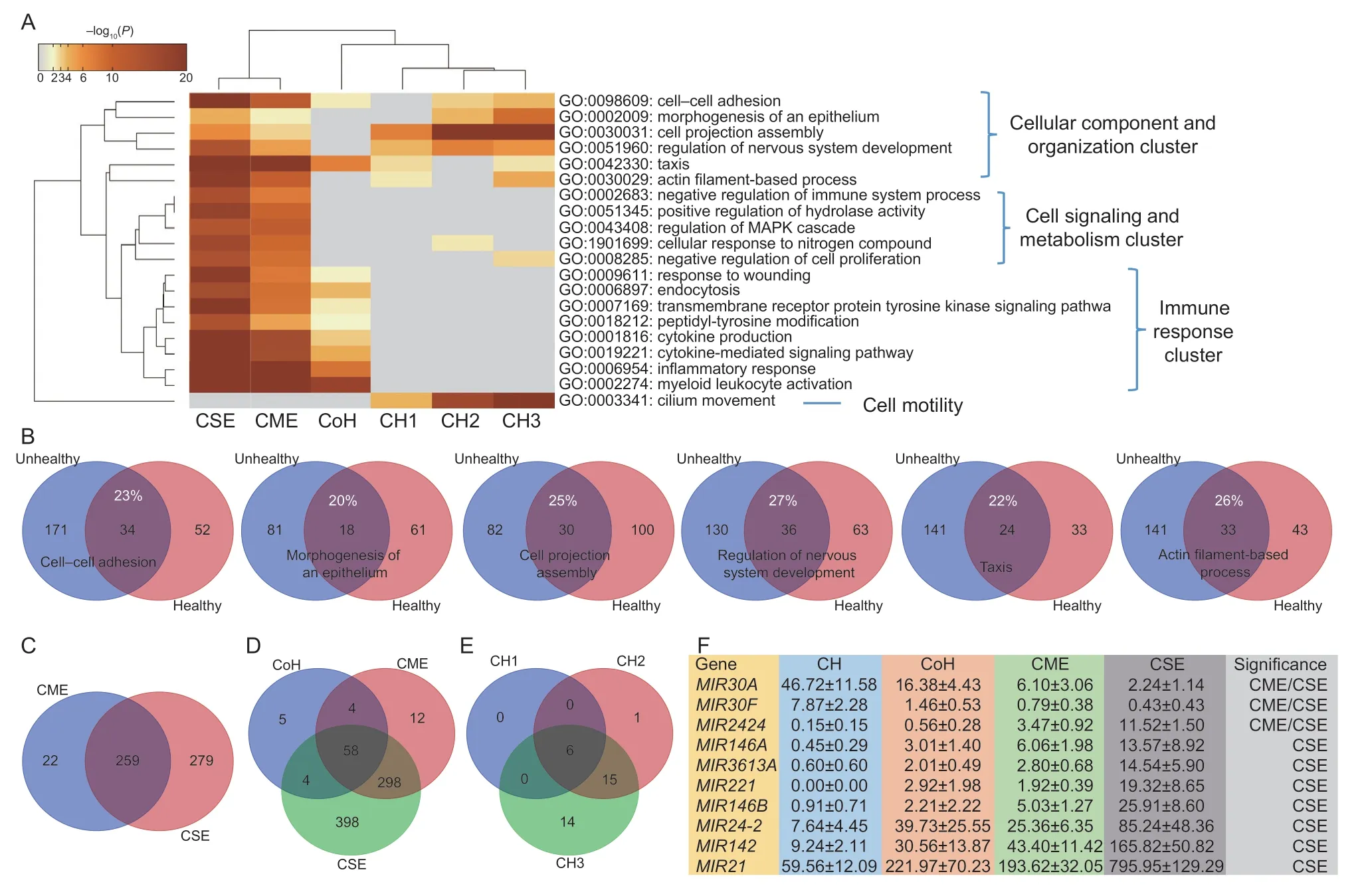

By excluding all DE-APA sites that were not currently annotated in the bovine genome,the final numbers of DE-APA sites/DE genes were 293/284 for CH1 and 274/241 for CoH;979/836 for CH2 and 2 282/1 573 for CME;and 2 283/1 766 for CH3 and 6 545/3 284 for CSE,respectively (Appendix B).Pathway enrichment with the Metascape program revealed 246 (CH1),205 (CoH),724(CH2),1 291 (CME),1 509 (CH3) and 2 673 DE genes(CSE) (Appendix D).Indeed,the enriched pathways of endometrial epithelial cells of cows that ranged from conditionally healthy to clinically severe endometritis were progressively “magnified” in terms of numbers of DE genes and log(q-value) (Appendix D) as compared to clinically healthy cows.Overall,we classified these 20 summary pathways into four functional clusters.

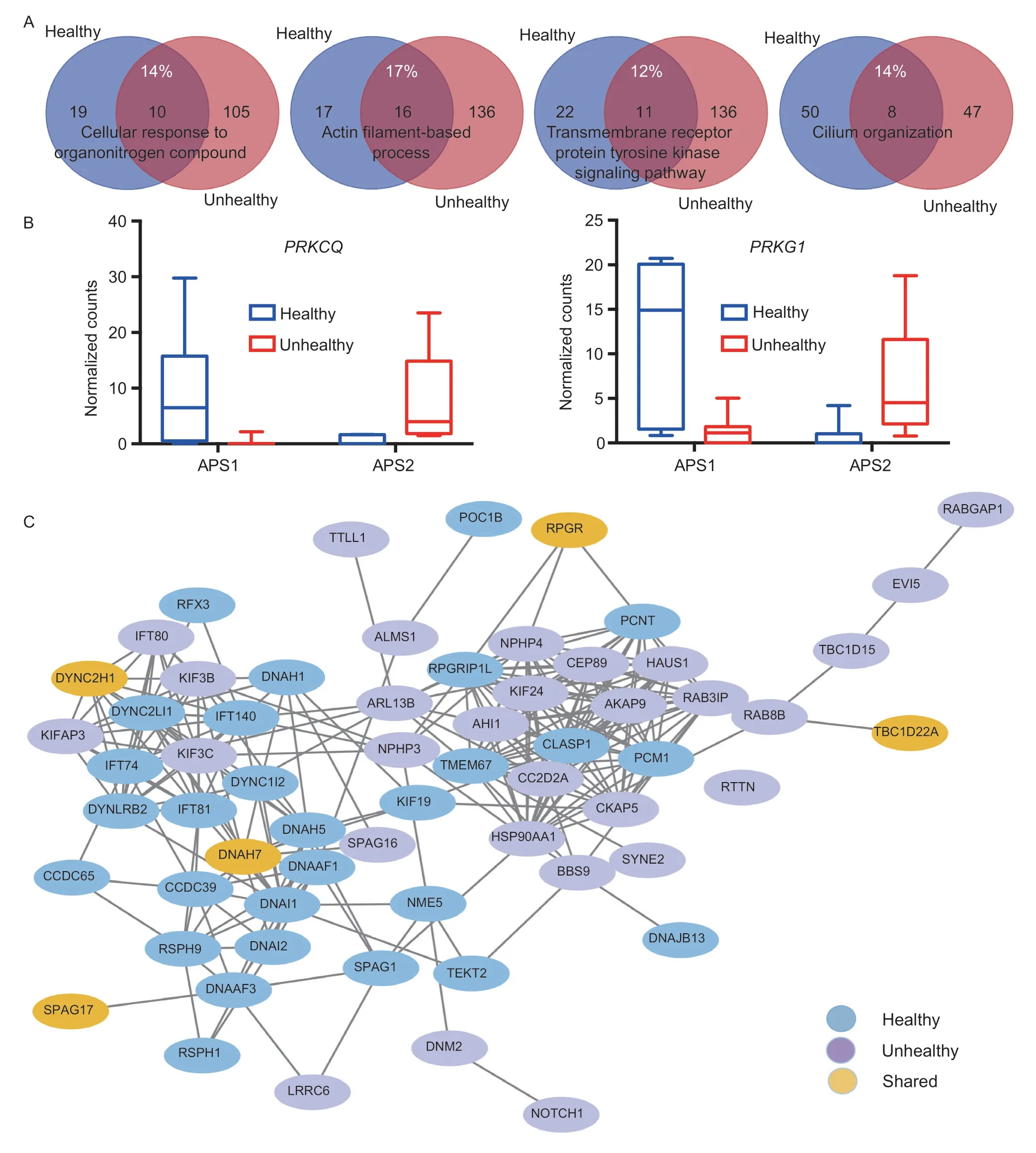

As shown in Fig.4-A,the first six “summary” pathways:cell–cell adhesion,morphogenesis of an epithelium,cell projection assembly,regulation of nervous system development,taxis and actin filament-based process represent the cellular component and organization cluster.The cell signaling and metabolism cluster included five pathways: negative regulation of immune system process,positive regulation of hydrolase activity,regulation of MAPK cascade,cellular response to nitrogen compound and negative regulation of cell proliferation.The immune response cluster involved pathways related to response to wounding,endocytosis,transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase signaling pathway,peptidyl-tyrosine modification,cytokine production,cytokine-mediated signaling pathway,inflammatory response and myeloid leukocyte activation.The cell motility pathway cluster had one only with cilium movement.

Fig.4 Characterization of endometritis progression in dairy cows.A,the top 20 “summary” pathways were classified into four clusters.B,6 pathways in the cellular component and organization cluster were shared,without many differentially expressed (DE)genes in common between CH (clinically healthy,n=4) and CoH (conditionally healthy,n=3),CME (clinically mild endometritis,n=6)and CSE (clinically severe endometritis,n=5) groups.C,5 pathways in the cell signaling and metabolism cluster were enriched for CME and CSE only.D,8 pathways in the immune response cluster were specific to CoH,CME and CSE groups.E,cilium movement was only pathway in CH cows.F,10 DE genes for microRNA genes were identified,but at least MIR30A and MIR21 can be used as biomarkers to determine endometritis progression in dairy cows.The values are presented as average±standard error in normalized units.

The cellular component and organization cluster had the same pathways enriched for CH (CH1,CH2 and/or CH3) and for CoH,CME and CSE,but the DE genes underlying them were quite different (Fig.4-B).The common DE genes ranged from 20% for morphogenesis of an epithelium to 27% for regulation of nervous system development.The cell signaling and metabolism cluster was mainly enriched for cows with either CME or CSE(Fig.4-C).Interestingly,CSE pathways almost doubled the numbers of DE genes in comparison to CME with 105vs.53,172vs.87,156vs.89,148vs.76 and 158vs.82 for these pathways,respectively (Appendix D).Among the eight pathways in the immune cluster,the number of unique DE genes increased from 71 in cows with CoH to 372 in cows with CME and 758 in cows with CSE,respectively (Fig.4-D).The cilium movement pathway only belonged to CH cows with 6,22 and 35 DE genes for CH1,CH2 and CH3 (Fig.4-E) in comparison to CoH,CME and CSE,respectively.

Closer examination of the immune response cluster revealed five genes: CD59 molecule (CD59),Fc fragment of IgG receptor IIa (FCGR2A),lymphocyte antigen 75(LY75),nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group H member 4(NR1H4),and plasminogen (PLG) and 12 genes: activin A receptor like type 1 (ACVRL1),arrestin beta 1 (ARRB1),complement factor B (CFB),C-type lectin domain containing 10A (CLEC10A),clathrin adaptor protein(DAB2),interferon regulatory factor 8 (IRF8),integrin subunit alpha V (ITGAV),NIMA-related kinase 1 (NEK1),3-phosphoinositide dependent protein kinase 1 (PDPK1),receptor activity modifying protein 3 (RAMP3),serpin family F member 2 (SERPINF2),and SH2B adaptor protein 2 (SH2B2) that were exclusive DE genes in CoH and CME cows,respectively (Fig.4-D;Appendix D).

Among 29 APA sites derived from 25 miRNA genes,two and nine sites were associated with healthy and unhealthy cows,respectively (adjustedP<0.01;Appendix B).AsMIR142had two significant sites,but expressed with the same trend,we combined them in the analysis.As such,average gene expression abundance and standard errors for a total of 10 miRNA genes are summarized in Fig.4-F.Two up-regulated miRNAs in CH cows areMIR30AandMIR30F,which were reduced by 44.48 (from 46.72 to 2.24)and 7.44 normalized units (from 7.87 to 0.43) in CSE cows,respectively.Among 8 up-regulated miRNAs in CSE cows,MIR21 had the largest increase by 736.39 normalized units(from 59.56 to 795.95) in comparison to CH cows,followed byMIR142andMIR24-2with an increase of 156.58 and 77.60,respectively (Fig.4-F).The remaining DE genes wereMIR146B,MIR221,MIR3613A,MIR146AandMIR2424that were significantly up-regulated in CSE cows.In addition,MIR2424was also significant between CME and CH cows.

Among these 10 DE miRNAs,MIR21,MIR24-2,MIR146AandMIR221were integrated in known pathways(Appendix D).MIR21was solely involved in 3 pathways:actin filament-based process,cytokine-mediated signaling pathway and positive regulation of hydrolase activity,whileMIR221was exclusively included in 2 pathways:regulation of nervous system development and peptidyltyrosine modification.Together,MIR21andMIR221contributed to 6 pathways: cell–cell adhesion,cytokine production,inflammatory response,morphogenesis of an epithelium,response to wounding and transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase signaling pathway.MIR21,MIR24-2andMIR221were involved in negative regulation of immune system process and regulation of MAPK cascade.These 4 microRNAs all contributed to negative regulation of cell proliferation (Appendix D).

4.Discussion

A few studies have been conducted at transcriptomewide level to unravel molecular mechanisms underlying endometritis in dairy cows.Using RNA samples derived from the endometrial biopsies and hybridized to the bovine GeneChip Genome Array (Affymetix,CA,USA),for example,Salilew-Wondimet al.(2016) found 92 up-regulated genes,but 111 down-regulated genes in CE cows,and 231 up-regulated/252 down-regulated genes in SE cows compared to HC cows.Pathway enrichment analysis of the DE genes identified the top 10 functional pathways including blood vessel development(2 up-regulatedvs.6 down-regulated DE genes plus 2 unmarked in affected individuals),cell adhesion (2 up-regulatedvs.9 down-regulated DE genes plus 2 unmarked),chemotaxis (1 up-regulatedvs.6 downregulated DE genes),enzyme linked receptor protein signaling pathway (2 up-regulatedvs.7 down-regulated DE genes plus 1 unmarked),G-protein coupled receptor signaling pathway (4 up-regulatedvs.3 down-regulated DE genes),immune system process (1 up-regulatedvs.14 down-regulated DE genes),regulation of apoptotic signaling pathway (4 up-regulatedvs.3 down-regulated DE genes),regulation of neurogenesis (1 up-regulatedvs.5 down-regulated DE genes plus 1 unmarked),response to endogenous stimulus (5 up-regulatedvs.5 down-regulated DE genes),and response to stimulus(16 up-regulatedvs.25 down-regulated DE genes).Among these ten pathways,seven had more down-than up-regulated DE genes in animals suffering from the endometritis.

On the other hand,Foleyet al.(2015) used RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) to detect transcriptome changes in endometrial biopsies between SE and HC at 7 and 21 days postpartum.They found that 54 and 19 DE genes were up-regulated at 7 days postpartum (FDR<0.1),respectively,while 948 and 219 genes were up-regulated at 21 days postpartum,respectively.Pathway enrichment analysis of the DE genes with Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) found the top 10 pathways included cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction,malaria,complement and coagulation cascades,Staphylococcus aureusinfection,osteoclast differentiation,Rheumatoid arthritis,B cell receptor signaling pathway,Toll-like receptor signaling pathway,systemic lupus erythematosus and Jak-STAT signaling pathway.Undoubtedly,these two studies described above differed dramatically in total numbers of DE genes detected,ratio of up-regulated DE genes between cows with and without the disease and Gene Ontology (GO) terms in response to endometrial infections.

Our present study is unique in several ways.First,our WTTS-seq method clearly revealed that pathogens upregulated more DE-APA sites/DE genes in endometrial epithelial cells of unhealthy cows in comparison to those of healthy cows without endometritis.Our WTTS-seq method is more sensitive than RNA-seq (Foleyet al.2015) because it revealed much larger differences between unhealthy and healthy cows in DE-APA sites with a ratio of 5.69 (8 802) to 1 (1 547) and in DE genes with a ratio of 3.45 (2 343) to 1 (679) (adjustedP<0.01,log2(fold change)>|2|).Second,DE-APA sites in unhealthy cows are more frequently located in introns than those in healthy cows (66%vs.51%),thus dramatically reducing usage of the distal APA sites to 9% in the former as compared to 21% in the latter group of animals.Third,we observed that unhealthy cows responded to pathogens by activating a higher number of DE-APA sites per gene than healthy cows (1.14 for CoH and 1.03 for CH1;1.45 for CME and 1.17 for CH2;and 1.99 for CSE and 1.29 for CH3,respectively) (Appendix B).Lastly,genes involved in inflammation were up-regulated as endometritis severity increased.For example,the number of unique DE genes that were enriched for immune pathways increased from 71 in cows with CoH to 372 in cows with CME and 758 in cows with CSE (Fig.4-D).

We believe that it was rational to characterize endometritis progression events by classification of these 18 cows into CH,CoH,CME and CSE groups based on their transcriptome relationships.CoH and CH originated from the healthy group based on subjective scores and their pathway relationships showed them clustered together (see CoH,CH1,CH2 and CH3 in Fig.4-A).The CoH group served as a starting point to understand how endometritis progresses towards CME and CSE status,particularly with eight immune-related pathways.The 71 DE genes identified in CoH cows were actually split into two categories: five (7%) exclusively expressed in the CoH cows and 66 (93%) extended to CME and/or CSE cows (Fig.4-D).Among the former group of DE genes,four encode cell surface markers,such as CD59 as surface glycoprotein (Stefanová and Horejsí 1991),FCGR2A as surface receptor (Kaczorowskiet al.2013),LY75 as surface antigen (Faddaouiet al.2016) and PLG as surface bridge (Sumitomoet al.2016).NR1H4is a nuclear receptor,which may stimulate T cells to produce type I interferon under induction of inflammagens (Honkeet al.2017).Among the latter group of DE genes,four contributed to at least 5 out of 8 immune pathways and they were AXL receptor tyrosine kinase (AXL),FGR protooncogene,Src family tyrosine kinase (FGR),HCK protooncogene,Src family tyrosine kinase (HCK) and integrin subunit beta 2 (ITGB2) (Appendix D).These genes encode products that are involved in anti-inflammation by AXL (van der Meeret al.2014),cell migration by FGR and HCK (Fumagalliet al.2007) and immune response by ITGB2 (Crozatet al.2011).Certainly,understanding how pathogens affect the function of these genes and how the endometrial epithelial cells coordinate activation/deactivation of these genes in response would lead to a better understanding of how dairy cows ultimately evade,clear,or develop endometritis.

Notably,our APA profiling also highlighted the importance of cilia in endometritis status.Endometrial epithelial cells possess both motile and non-motile cilia function and cilium organization,cilium-dependent cell motility,non-motile cilium assembly,cell part morphogenesis,axonemal central apparatus assembly,intraciliary transport and cilium movement pathways were enriched in the present study (Figs.2-C and D,and 3-A).Motile cilia are essential for embryo fertilization and implantation,as they are required to move ova and fertilized eggs along the reproductive tract (Hagiwaraet al.2000;Enukaet al.2012;Wanget al.2015).In particular,the WTTS-seq method is sensitive enough to detect both sets of DE genes related to cilium function for healthy and unhealthy cows even with potentially separated trends in protein–protein interaction (PPI) (Fig.3-C).Among them,5 genes: dynein cytoplasmic 2 heavy chain 1 (DYNC2H1),dynein axonemal heavy chain 7 (DNAH7),retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR),sperm associated antigen 17 (SPAG17) and TBC1 domain family member 22A (TBC1D22A),each expressed DE-APA sites specific to each condition (Appendix B).

In CH cows,MIR30Awas expressed more abundantly thanMIR30F.The former microRNA gene regulates autophagic activity,anti-inflammatory effect and cell invasion,migration and cell proliferation (Chenget al.2015;Demolliet al.2015;Zhanget al.2016;Parket al.2017).Among 3 inflammation-related microRNAs investigated by Prabowoet al.(2015) and 2 (MIR21andMIR146,includingMIR146AandMIR146B) appeared as DE genes dominantly expressed in CSE cows in the present study (Fig.4-F).In particular,MIR21was the most significant DE gene among the 10 microRNAs and was highly associated with severe endometritis and was involved in 11 pathways.Furthermore,our present study revealed at least one pair of antagonistic microRNAs:MIR30Aas anti-inflammation andMIR21as inflammation microRNA genes.As such,we propose that both can be used as biomarkers for diagnosis of endometritis severity in dairy cows.

5.Conclusion

This is the first report on alternative polyadenylation events altered by endometritis in cattle.Gene biotypes had significant effects on usages of APA sites,their cleavage sites and adjacent genomic features.Pathogens caused APA to switch from distal to intronic sites,thus potentially changing protein properties for malfunction.We confirmed that endometrial inflammation is induced by cytokines,cytokine-associated proteins and/or cytokine–cytokine receptor interactions.Differentially expressed microRNA genes can serve as diagnosis markers to measure inflammation severity in endometrium.Recovery of the lost cilial function in endometrial epithelial cells due to endometritis should be targeted in development of novel drugs and strategies to improved fertility in dairy cows.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture,United States Department of Agriculture(2016-67015-24470,2018-67015-27500 (sub-contract),2020-67015-31733 and 2022-51300-38058) and by funds provided for medical and biological research by the State of Washington Initiative Measure,USA (No.171) and the Washington State University Agricultural Experiment Station (Hatch funds 1014918) received from the National Institutes for Food and Agriculture,United States Department of Agriculture.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The animal use protocol was reviewed and approved by the Washington State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee,USA.

Appendicesassociated with this paper are available on https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jia.2022.11.009

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年6期

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年6期

- Journal of Integrative Agriculture的其它文章

- ldentification of two novel linear epitopes on the p30 protein of African swine fever virus

- Uncertainty aversion and farmers’ innovative seed adoption:Evidence from a field experiment in rural China

- Ensemble learning prediction of soybean yields in China based on meteorological data

- Increasing nitrogen absorption and assimilation ability under mixed NO3– and NH4+ supply is a driver to promote growth of maize seedlings

- Significant reduction of ammonia emissions while increasing crop yields using the 4R nutrient stewardship in an intensive cropping system

- Maize straw application as an interlayer improves organic carbon and total nitrogen concentrations in the soil profile: A four-year experiment in a saline soil