Diurnal emission of herbivore-induced (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate and allo-ocimene activates sweet potato defense responses to sweet potato weevils

XlAO Yang-yang ,QlAN Jia-jia ,HOU Xing-liang ,ZENG Lan-ting,LlU Xu,MEl Guo-guo,LlAO Yin-yin#

1 Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Digital Botanical Garden and Popular Science/Key Laboratory of South China Agricultural Plant Molecular Analysis and Genetic Improvement, South China Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences,Guangzhou 510650, P.R.China

2 College of Life Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, P.R.China

3 Center of Economic Botany, Core Botanical Gardens, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510650, P.R.China

Abstract The sweet potato weevil (Cylas formicarius (Fab.) (Coleoptera: Brentidae)) is a pest that feeds on sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.(Solanales: Convolvulaceae)),causing substantial economic losses annually.However,no safe and effective methods have been found to protect sweet potato from this pest.Herbivore-induced plant volatiles (HIPVs)promote various defensive bioactivities,but their formation and the defense mechanisms in sweet potato have not been investigated.To identify the defensive HIPVs in sweet potato,the release dynamics of volatiles was monitored.The biosynthetic pathways and regulatory factors of the candidate HIPVs were revealed via stable isotope tracing and analyses at the transcriptional and metabolic levels.Finally,the anti-insect activities and the defense mechanisms of the gaseous candidates were evaluated.The production of (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate (z3HAC) and allo-ocimene was induced by sweet potato weevil feeding,with a distinct circadian rhythm.Ipomoea batatas ocimene synthase (IbOS) is first reported here as a key gene in allo-ocimene synthesis.Insect-induced wounding promoted the production of the substrate,(Z)-3-hexenol,and upregulated the expression of IbOS,which resulted in higher contents of z3HAC and allo-ocimene,respectively.Gaseous z3HAC and allo-ocimene primed nearby plants to defend themselves against sweet potato weevils.These results provide important data regarding the formation,regulation,and signal transduction mechanisms of defensive volatiles in sweet potato,with potential implications for improving sweet potato weevil management strategies.

Keywords: sweet potato,(Z)-3-hexenyl acetate,allo-ocimene,defense,signaling

1.lntroduction

Native to Central America,the sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas(L.) Lam.(Solanales: Convolvulaceae)) is now cultivated worldwide,and it is the seventh most important cash crop in terms of total grain output (Laurieet al.2015).The global popularity of sweet potato is increasing because it can be grown relatively easily without strict environmental requirements and produces more calories per hectare than most major food crops,such as rice and wheat.This productivity has helped to counteract hunger in less-developed countries and regions.Compared with many food crops,sweet potato contains various nutrients required by humans,such as β-carotene and vitamin A,so it is useful for preventing micronutrient deficiency,especially in areas affected by poverty (Whitmeeet al.2015).Sweet potato can adapt to extreme environmental conditions,such as lack of water or soil nutrients,drought,and high temperature,but its yield and quality are adversely affected by diseases and insect pests.For example,infestation by insect pests can decrease sweet potato production by up to 80% in the field (Braun and Van De Fliert 1999).Globally,the sweet potato weevil(Cylasformicarius(Fab.) (Coleoptera: Brentidae)) is the most dangerous invasive pest affecting sweet potato.It is a ubiquitous pest that feeds on the stems,leaves,and roots,and also lays its eggs in the roots,thereby decreasing the yield and quality of sweet potato at the preharvest and postharvest stages (Liaoet al.2020).Chemical control and agronomic measures can protect sweet potato from these weevils,but these measures are either harmful to humans and the environment or they are costly and not very efficient (Braun and Van De Fliert 1999).Thus,a novel strategy to manage these pests is needed.

When plants are subjected to stress by insects,they synthesize and release various herbivore-induced plant volatiles (HIPVs),such as green leaf volatiles (GLVs),terpenoids,and phenylpropanoid derivatives,through various pathways (Dudarevaet al.2006).Herbivoreinduced plant volatiles have been reported to repel insect pests and inhibit their growth,while also attracting the natural enemies of these plant pests (Liaoet al.2021).The role of HIPVs as signaling molecules that mediate communication between plants has recently attracted growing interest (Engelberthet al.2004).Thus,HIPVs are potentially useful for developing a new comprehensive integrated pest management strategy that can safely protect crops from insect infestations (Wang and Kays 2002).A previous study demonstrated that the leaves of sweet potato (Tainong 57) released a large amount of(E)-4,8-dimethyl-1,3,7-nonene (DMNT) in response to an insect infestation,which subsequently promoted the activity of the protease inhibitor,sporamin,in neighboring sweet potato plants to enhance their resistance to the insects (Meentset al.2019).Therefore,the present study aims to identify other potential anti-herbivore volatiles in sweet potato and then explore the mechanisms mediating their formation,regulation,and defense-related effects.

2.Materials and methods

2.1.Chemicals and reagents

For this study,the following reagents and equipments were purchased from the sources indicated: dichloromethane(chromatographic grade) from Tianjin Fuchen Chemical Reagent Co.,Ltd.(Tianjin,China);acetonitrile (MS grade)and formic acid (MS grade) from Thermo Fisher Scientific,Inc.(Pittsburgh,PA,USA);SPME fibers from Supelco Inc.(solid-phase Microextraction,2 cm–50/30 μm DVB/CarboxenTM/PDMS Stable FlexTM,Bellefonte,PA,USA);(Z)-3-hexen-1-ol,z3HAC,allo-ocimene and [2H2](Z)-3-hexen-1-ol standards from Shanghai Zhenzhun Bio Co.,Ltd.(Shanghai,China);(E)-β-ocimene from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co.,Ltd.(Shanghai,China);n-alkane from Sigma-Aldrich (St.Louis,MO,USA);chlorogenic acid from Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology Co.,Ltd.(Shanghai,China);jasmonic acid (JA) from Tokyo Chemical Industry (Tokyo,Japan);salicylic acid(SA) and abscisic acid (ABA) from Aladdin Industrial Co.,Ltd.(Shanghai,China);a plant RNA rapid extraction kit from Huayueyang Biotechnology Co.,Ltd.(Beijing,China);fluorescent quantitative dye (iTaqTM Universal SYBR?Green Supermix) and restriction enzyme (EcoRI andBamHI) from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules,CA,USA);a Reverse Transcription Kit,In-fusion HD Cloning Kit and PrimerSTAR Max DNA Polymerase Kit from TaKaRa Bio Inc.(Kyoto,Japan);a DNA purification kit from Zymo Research (Irvine,CA,USA);competent cells ofEscherichcoliDH5α andAgrobacteriumtumefaciensstrain GV3101-pSoupfrom Novagen Inc.(Madison,WI,USA);and the deionized water was prepared from a super-pure water system (Synergy UV;Merck,Darmstadt,Germany).

2.2.Plant materials and treatments

Ipomoeabatatas(N73) andNicotianabenthamianawere planted in the South China Botanical Garden,Chinese Academy of Sciences (Guangdong,China).Sweet potato shoots (about 5–6 sweet potato leaves per shoot) were pruned and supplied with distilled water for 12 h before formal sample processing.During the plant treatment,sweet potato shoots were cultured in an artificial climate incubator (25°C,light intensity 8 500 lux,relative humidity 70%).Sweet potato weevils (C.formicarius) were captured from the sweet potato field and identified by Prof.Zhu Hongbo at the Guangdong Ocean University.Adult sweet potato weevils at the same developmental stage were used for the experiment,and sweet potato weevils were randomly selected without discrimination by sex.Sweet potato weevils were starved for 12 h before each experiment conduction.

Several treatments were used: two different wounding treatments,a JA treatment,a sweet potato weevil treatment,a [2H2](Z)-3-hexen-1-ol feeding treatment,and fumigation treatments withz3HAC andallo-ocimene.

Two continuous wounding treatments were used to induce stress.For treatment 1,one sweet potato shoot as a biological replicate was placed in a 500-mL beaker sealed with foil at the top and cultured in an artificial climate incubator for 3 h.Each leaf of the shoot was pierced with a syringe needle 10 times every 15 min.The volatiles in the headspace of the beaker were collected with an SPME fiber for 3 h.The control group was left untreated and cultured under the same conditions.All experiments were conducted in triplicate.After 3 h of treatment,the SPME fibers were collected and the samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen,then quickly stored at–80°C for later analysis.

For treatment 2,the same procedure was used but the shoots were cultured in an artificial climate incubator for 24 h (15 h light/9 h dark).Each leaf of a shoot was pierced with a syringe needle 10 times every 3 h.The volatiles in the headspace of the beaker were collected with an SPME fiber for 24 h.The control group was left untreated and cultured under the same conditions.Each experiment was conducted with three replicates.The SPME fibers and the plant samples were processed as described above.

For the sweet potato weevil treatment,one sweet potato shoot as a biological replicate was placed in a 500-mL beaker sealed with foil at the top and treated with 20 sweet potato weevils.The samples were cultured in an artificial climate incubator for 24 or 48 h (15 h light/9 h dark).The volatiles in the headspace of the beaker were collected with an SPME fiber for a total of 6 h starting at the 18th and 42nd h after the beginning of the culturing,respectively.In the control group,sweet potato shoots were supplied with distilled water without sweet potato weevils,then cultured under the same conditions for 24 or 48 h.Three biological replicates were conducted.The SPME fibers and sweet potato samples were processed as described above.

For the [2H2](Z)-3-hexen-1-ol feeding treatment,one sweet potato shoot as a biological replicate was placed in a 500-mL beaker sealed with foil at the top and treated with [2H2](Z)-3-hexen-1-ol solution (0.4 mmol L–1with 1% ethanol as cosolvent).The samples were cultured in an artificial climate incubator for 12 h.The volatiles in the headspace of the beaker were collected with an SPME fiber for 12 h.The control group was treated with 1% ethanol,then cultured under the same conditions.All experiments were performed with three biological replicates.The SPME fibers and tissue samples were processed as described above.

For the fumigation treatments withz3HAC andalloocimene,three sweet potato shoots were fumigated in a sealed glass jar with a cotton ball suspended above.Either 50 mmol L–1z3HAC orallo-ocimene(dichloromethane as cosolvent) was dropped into the cotton ball.The control group was treated with the same volume of dichloromethane.The samples were cultured in an artificial climate incubator for 12 h.Each sweet potato shoot represented a biological replicate,and sample processing was conducted as described above.

2.3.Monitoring the emission profiles of volatiles from sweet potato shoots exposed to sweet potato weevils

The continuous monitoring was carried out as described by Liaoet al.(2021) and Jianet al.(2021) with some modifications.The volatiles induced by 20 sweet potato weevils from two sweet potato shoots,each with 5–6 leaves and cultivated in water (25°C,60% relative humidity),were collected using an adsorption column.The column was replaced by a new column every 6 h.The total monitoring time was 72 h and each group had 5 replicates.The control group was not exposed to sweet potato weevils but was cultured under the same conditions.The volatiles collected in the adsorption columns were analyzed by GC-MS.The GC-MS system was equipped with a SUPELCOWAX 10 column (Supelco Inc.,Japan,30 m×0.25 mm×0.25 mm).The injector temperature was set at 230°C for 1 min,and the split ratio was 32:1.The helium (carrier gas) flow rate was 1.0 mL min–1.The GC temperature was set at 60°C for 3 min,then increased at 4°C min–1to 240°C,and maintained at 240°C for 20 min.The mass spectrometer (Shimadzu Corp.,Kyoto,Japan)was operated in full scan mode (mass range,m/z40–200).The volatile components were identified by comparison with standard compounds.Retention indices (RIs) or mass spectra in the NIST library.(Z)-3-hexenol,(Z)-3-hexenyl acetate,allo-ocimene and β-ocimene were identified by direct comparisons with their authentic standards.The RIs of the compounds were calculated from then-alkane series (C7–C40).Compounds with minor differences (less than 20) between the experimental RI and reference RI values cited in the literature were confirmed as common components.The other compounds with no standards or reference RI values available were identified by comparison with mass spectra in NIST 11,and these compounds were considered to be only tentatively identified.Characteristic ion fragments and standard alignment were used for the qualitative analyses ofz3HAC (m/z67 and 82) andallo-ocimene (m/z121 and 136).A standard curve was constructed and the sample concentration was determined based on the standard curve.

2.4.Collection and determination of z3HAC and allo-ocimene in sweet potato leaves

The method described by Jianet al.(2021) was used with some adjustments.The sample volatiles were detected by a GC-MS system (QP2010 SE,Shimadzu Corp.,Japan) equipped with GC-MS Solution Software (Version 2.72).The SPME fibers were injected into the GC injection port in the splitless mode and held at 230°C for 15 min.The volatile compounds were separated through a SUPELCOWAX 10 column (30 m×0.25 mm×0.25 μm,Supelco Inc.,Japan).The flow rate of the helium carrier gas was 1.0 mL min–1.The initial GC oven temperature was 40°C for 3 min,increased to 100°C at 2°C min–1,then increased to 240°C at 20°C min–1and held for 20 min.The mass spectrometer was operated in full scan mode,over a mass range ofm/z40–200.The characteristic ions ofz3HAC arem/z67 and 82,whilem/z69 and 84 represent [2H2]z3HAC.The characteristic ions ofalloocimene arem/z121 and 136.The qualitative analyses ofz3HAC andallo-ocimene in sweet potato were based on the retention times of the standards.In the present study,z3HAC andallo-ocimene were collected by SPME,not in samples extracted with organic solvents.SPME cannot be used for accurate quantitation using a standard curve,so the relative quantifications ofz3HAC andalloocimene in sweet potato were based on the areas of thez3HAC andallo-ocimene peaks from the mass spectra.

28. Drunken hussar: A hussar is a European solider, usually a cavalry72 officer. Von Franz points out that the hussar, symbolizes a brutal73 outburst of emotion. The wild ungovernable animus smashes everything, showing clearly that such an exhibition of her unconscious nature does not work (175). This is also another aspect of Wotan (von Franz 175). According to von Franz, the horse the hussar rides is connected to the animus and respects instinctive74 animal nature (176).Return to place in story.

2.5.Extraction and determination of phytohormones in sweet potato leaves

The extraction and determination of phytohormones in sweet potato leaves were performed as described by Liaoet al.(2020).The sample processing protocol is shown in Appendix A.

2.6.Extraction and determination of phenolic acids in sweet potato leaves

The extraction and determination of phenolic acids in sweet potato leaves were performed as described by Liaoet al.(2020) with modifications.The sample processing protocol is shown in Appendix B.

2.7.Transient overexpression of IbOS in tobacco(Nicotiana benthamiana) leaves

Transient expression was performed with tobacco(Nicotianatabacum) leaves as previously reported with limited modification (Jianet al.2021).The candidate genes (IbOS) of sweet potato were obtained by screening our sweet potato transcriptome data by keyword (ocimene synthase) searching (sequences ofIbOS1–3were uploaded onto NucBank,with assigned accession numbers of C_AA001108.1,C_AA001109.1,and C_AA001110.1,respectively).The full-length open coding frames (ORFs) of theIbOS1andIbOS2genes were cloned then inserted into the pGreen-35S-GFP vector,carrying green fluorescent protein(GFP) and an ER-targeted marker.The fusion gene was generated under the control of the 35S promoter.The primers used to construct the vectors for IbOS1 and IbOS2 were: F: 5′-GCTTGATATCGAATTCA T G T C T C T T C AT C T T G T C T C T C TAT C C C-3′,R:5′-TCATACTAGTGGATCCTTCTTGCCCAGGCAAGGC a n d F: 5′-G C T T G ATAT C G A AT T C AT G T C T C T TCATCTTGTCTCTCTATCCC-3′,R: 5′-TCATACTA GTGGATCCAAGAAATGTCTTCATTCTTGCCCA-3′,respectively.TheAgrobacteriumstrains GV3101-pSoupcarrying the recombinant plasmids were grown in liquid Luria-Bertani (LB) media supplemented with 100 μg μL–1rifampicin and 50 μg μL–1kanamycin.The cells were harvested and resuspended in infiltration medium to an OD600value of 1.0–1.2.The infiltration medium consisted of 10 mmol L–1MES (pH 5.6),10 mmol L–1MgCl2and 150 μmol L–1acetosyringone.TheAgrobacteriumsuspensions were infiltrated into 4-week-old tobacco leaves.The leaf samples were cultured for 48 h after infiltration,then placed into a 250-mL beaker sealed with foil at the top.The volatiles in the headspace of the beaker were collected with an SPME fiber for 1.5 h.All experiments were conducted in triplicate.The SPME fibers were collected for detection,and the samples were extracted and analyzed using GC-MS.

2.8.Subcellular localization of the lbOS protein in protoplasts of Arabidopsis thaliana

The coding sequence ofIbOS1were cloned into pGreen-35S-GFP (C18) containing a GFP open reading frame as the reporter gene.TenA.thalianaleaves of 4-week-old were digested in enzyme solution (1.5% cellulose R10,0.3% macerozyme,0.4 mol L–1mannitol,20 mmol L–1KCl and 20 mmol L–1MES,pH 5.7) for at least 1 h at 25°C.Then the protoplasts were isolated,and then transformed and cultured with PEG and W5 solutions,respectively.In addition,the expression construct C18-IbOS1-GFP and ER-marker were co-transformed into protoplasts.The fluorescence of CsCYP79-GFP was observed using confocal laser-scanning microscopy (Zeiss LSM 510,Carl Zeiss,Jena,Germany).

2.9.Effects of z3HAC and allo-ocimene on neighboring undamaged sweet potato shoots

The anti-herbivore activity was evaluated as described by Liaoet al.(2020) with some modifications.Six sweet potato shoots were fumigated in a sealed glass jar withz3HAC (50 mmol L–1,dichloromethane as cosolvent)dropped onto a sponge ball,while the control group was treated with the same volume of dichloromethane.Theallo-ocimene treatment group was treated with 50 mmol L–1allo-ocimene in dichloromethane,with 25 replicates in each group.These plant materials were cultured in an incubator for 12 h.After fumigation,the sweet potato shoots were removed,and seven sweet potato weevils were placed on one leaf wrapped in a mesh bag.The insect feeding occurred in the incubator (16 h light/8 h dark) for 24 h.Finally,photographs of each treated leaf were taken and used to calculate the area of leaf injury using Image J Software (version 1.51a).

2.10.Transcript expression analysis of volatile synthesis genes and defense genes in sweet potato leaves

The method is described by Livak and Schmittgen (2001),and detailed information is provided in Appendices C and D.

2.11.Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of differences between two groups was determined using Student’st-test (Microsoft Excel 2016).Differences between two groups,marked as*forP≤0.05 and**forP≤0.01,were considered statistically significant.

3.Results and discussion

3.1.Continuous invasion by sweet potato weevils induces the rhythmic release of z3HAC and allo-ocimene from sweet potato shoots

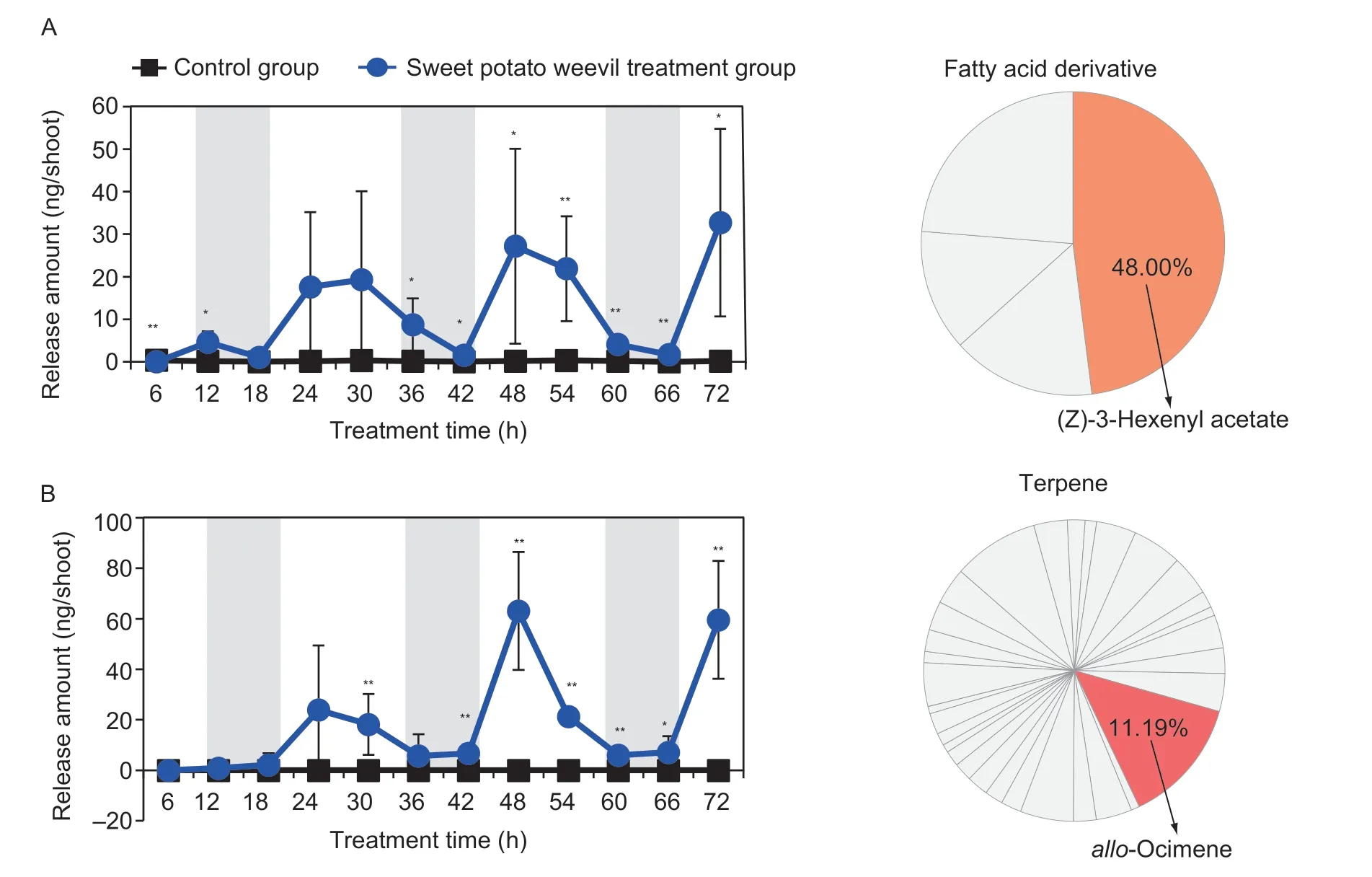

To identify the volatiles related to defense in sweet potato,the volatile compounds from the shoots were monitored continuously during an invasion by sweet potato weevils.Forty-six volatile compounds were identified,including four fatty acid derivatives,thirty-two terpenoids,eight phenylpropanoids,and two other compounds(Appendix E).Among these volatiles,the levels of bothz3HAC andallo-ocimene induced by insect infestation exhibited circadian rhythms,indicating that a potential function may exist (Fig.1).z3HAC andallo-ocimene were the most prominent fatty acid derivative and terpenoid compounds,accounting for 48.00 and 11.19%,respectively (Fig.1).Although they were all released at high levels during the day and low levels during the night,there was a lag period in their response to the insects.The releases ofz3HAC increased rapidly within 12 h of the infestation,whereasallo-ocimene was not emitted until 24 h after the infestation (Fig.1).

Fig.1 Release dynamics of the volatiles released from sweet potato shoots under continuous invasion by sweet potato weevils.A,(Z)-3-Hexenyl acetate.The white and gray column show the light and dark,respectively.B,allo-Ocimene.All data are expressed as mean±SD (n=5).Significant differences between control and treatment groups are indicated (*,P≤0.05 and **,P≤0.01),as determined by the independent Student’s t-test.

Plants that are attacked by insect pests during their growth have evolved several defense mechanisms that respond specifically to the insects,such as morphological alterations,regulatory changes to molecular networks,and biochemical responses.Insect infestation generally modulates the contents of metabolites related to plant defense,such as protease inhibitors,phenolic compounds,nitrogen compounds,sulfur compounds,and volatile metabolites (Fürstenberg-H?gget al.2013).Regarding these various compounds,research interest in HIPVs is increasing because these chemical signals mediate remote interactions between plant and plant,as well as among plant and insect and natural enemy.HIPVs are also perceived by the distal parts of injured plants(intraplant signals),neighboring plants (interplant signals),pests,and various natural enemies responsive to ‘plant distress signals’ (Turlings and Erb 2018).When HIPVs are emitted into the environment,they are rapidly diluted to inactive concentrations depending on various abiotic environmental factors.Thus,their effects are relatively brief and limited to a small area.The appropriate timing of the release of plant volatiles is essential for the efficient defense activities that may influence the oviposition behavior of pests,the feeding activity of larvae,and the behavior of natural enemies (Jooet al.2019).Unfortunately,research regarding the release dynamics of volatile metabolites in sweet potato is limited.

Green leaf volatiles are the class of compounds that respond most rapidly to an insect invasion,and they are often used as an indicator of plant responses to external stress.Their release dynamics largely depend on the insect feeding behaviors (Jooet al.2018;Liaoet al.2020).Within seconds of an insect infestation,a detectable amount of (Z)-3-hexen-1-al was emitted byA.thaliana,followed by the release of (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol andz3HAC within minutes (Fenskeet al.2015).Compared with the production of GLV,thedenovosynthesis of terpenoids in plants is often slower.Monoterpenes,such as limonene,linalool,andβ-ocimene,and sesquiterpenes,such as caryophyllene and farnesene,are usually released 24 h after injury.Previous research has revealed the mechanism of the rhythmic release of many monoterpenoids and sesquiterpenoids by plants (Jooet al.2018;Jianet al.2021).The temporal dynamics of plant volatile release are co-regulated by several internal and external factors,such as the biological clock,light,temperature,and insect behavior.Of these,the feeding rhythm of insects is likely to be the main factor as most HIPVs are induced by herbivores.Interestingly,even within a single plant–herbivorous insect system,different categories of volatiles can exhibit completely different release rhythms,suggesting that other abiotic factors are involved in the associated coordinated regulation.Circadian clock factors,such as LATE ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL (LHY) and ZEITLUPE (ZTL),can regulate the expression of genes encoding enzymes upstream of the GLV and terpenoid synthesis pathways,thereby affecting the synthesis of volatiles during the day (Fenskeet al.2015;Yonet al.2016).Exposure to light can activate the 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate (MEP)pathway and the expression ofBEATgenes related to the phenylpropanoid volatile synthesis pathway (Pokhilkoet al.2015;Jooet al.2018).Light can also affect the behavior of herbivorous insects,resulting in changes in the emission of volatiles (Jooet al.2019).In addition to influencing the timing of synthesis,the regulated transport of volatiles also determines the timing of release.For example,recent research has demonstrated that ATPbinding cassette (ABC) transporters can transport aromatic volatiles on petunia petal cell membranes and revealed the circadian rhythm of the expression levels of the genes encoding ABC transporters (Jianet al.2021;Skaliteret al.2021).The joint regulation of these mechanisms facilitates the unique release modes of the various HIPVs.The more precise characterization of the regulatory network of HIPVs in future investigations will probably allow researchers to incorporate these volatile compounds into new pest control measures which are highly efficient and environmentally-friendly,and could be applicable to the cultivation of sweet potato.

3.2.lnsect-induced injury provokes z3HAC through the accumulation of (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol

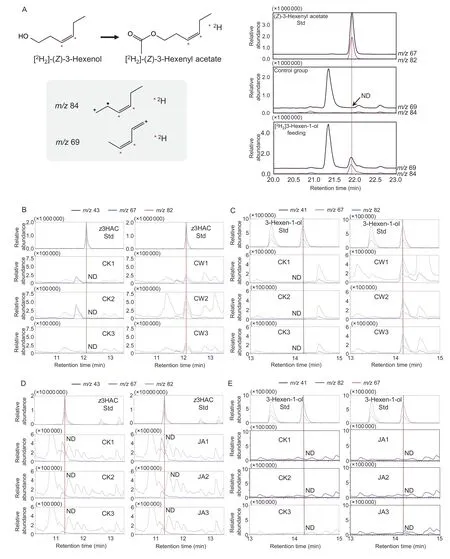

In plants,z3HAC is primarily synthesizedviathe lipoxygenase pathway.To determine the pathway involved in the synthesis ofz3HAC in sweet potato,we conducted a stable isotope tracing experiment using[2H2](Z)-3-hexen-1-ol (Fig.2-A).After a 12-h feed,[2H2]z3HAC accumulated rapidly in sweet potato shoots,whereas [2H2]z3HAC was undetectable in the controls(Fig.2-A).Therefore,thez3HAC in sweet potato leaves was derived from (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol.Insect infestation can damage plants,leading to the induction of the JA signaling pathway (Liaoet al.2020).Regarding the effect of continuous injury on the synthesis ofz3HAC,a 3-h continuous mechanical injury can induce the release of (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol andz3HAC (Fig.2-B and C).However,under JA treatment,both (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol andz3HAC were undetectable,implying thatz3HAC was not regulated by the JA signaling pathway in the present study(Fig.2-D and E).Therefore,the plant injury resulting from the insect infestation increased the (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol content and promoted the accumulation ofz3HAC (Fig.2).

Fig.2 Effect of sweet potato weevils on the formation of (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate (z3HAC).A,elucidation of the biosynthetic pathway of (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate using isotope tracing experiments.* indicates the 2H atom.B and C,effect of continuous wounding treatment on the release of (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate and (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol.D and E,effect of jasmonic acid treatment on the release of (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate and (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol.CK,corresponding control group;CW,continuous wounding treatment group;JA,jasmonic acid treatment group;ND,not detected;Std,standard.

Green leaf volatiles are a class of alcohols,aldehydes,and ester derivatives with a C6 skeleton that originates from long-chain unsaturated fatty acids,such as linoleic and linolenic acids.They are produced in reactions catalyzed sequentially by a series of enzymes.Lipoxygenase (LOX) and hydroperoxide lyase (HPL) are two key enzymes in the GLV synthesis pathway.More specifically,LOX catalyzes the conversion of unsaturated fatty acids to unsaturated fatty acid hydroperoxides,which are then cleaved by HPL to produce C6 components,such as (Z)-3-hexen-1-al,which is further processed by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and alcohol acetyltransferase(AAT) to producez3HAC (Xuet al.2019).The remaining C12 group produced by HPL is converted to endogenous hormones in plants,such as JA,methyl jasmonate,and jasmonate-isoleucine.z3HAC is generally synthesized from (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol in a reaction catalyzed by AAT.In the present study,a stable isotope tracing experiment confirmed the existence of the same synthesis pathway in sweet potato.Alcohol acetyltransferases are members of the BAHD acetyltransferase family (D’Auriaet al.2007).The diversity in the sequences of these family members may be related to the broad substrate specificity of the enzymes,which can catalyze the condensation of various fatty alcohols and phenols with different acylcoenzyme A (CoA) cofactors to produce volatile lipids and other compounds (D’Auriaet al.2007).AATs have also been detected in the fruit and flowers of many species,such as apple,strawberry,and jasmine,contributing to their characteristic aromas.A highly specific acetyl CoA(Z)-3-hexen-1-ol acetyltransferase (CHAT) has been identified inA.thaliana(D’Auriaet al.2007).In the present study,theAtCHATsequence was used to screen for the corresponding sweet potato gene.However,the candidate genes identified exhibited low sequence similarities and the encoded proteins did not catalyze the conversion of (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol toz3HAC.Therefore,the CHAT-encoding genes in sweet potato will need to be identified in future studies.Jooet al.(2018) reported that the biological rhythm-related factor,LHY,is involved in regulating the high diurnal and low nocturnal rhythmic release of pest-induced (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol.Therefore,the consistent synthesis of the substrate (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol may lead to the consistent rhythmic cycling ofz3HAC release.

Plant defense responses to herbivorous pests can be induced by both the mechanical damage caused by insect feeding and the inducers present in insect saliva.As sessile organisms,plants are inevitably damaged by the external environment during their life cycle,so they need a complex chemical signal-based regulatory system that can minimize the adverse effects of mechanical damage.Both JA and GLVs are formed after linolenic and linoleic acids are dissociated from the membrane lipids of cells ruptured during insect feeding.The fact that 13(S)-hydroperoxyoctadeca-9(Z),11(E) and 15(Z)-trienoic acid from the lipoxygenase pathway is the precursor of both JA and GLVs suggests the presence of substrate crosstalk between the two oxylipin cascades.Previous studies have revealed that mechanical injury and JA treatment can inducez3HAC production in some plants (Piesiket al.2010;Liaoet al.2020).An increase in the JA content may reduce the competition for GLV substrates,thus promoting the synthesis ofz3HAC.Interestingly,the JA treatment in the present study did not induce the synthesis of (Z)-3-hexenol orz3HAC in sweet potato,possibly due to differences in the sample treatment methods,the JA concentration and the duration of treatment.The species specificity of JA-induced GLVs should also be considered,and the specific underlying mechanism will need to be thoroughly investigated.

3.3.lnsect infestation up-regulates the expression of IbOS to produce allo-ocimene through injury and JA pathways

allo-Ocimene,a monoterpenoid,is synthesizedviathe MEP pathway (Fig.3-A).To confirm theallo-ocimene biosynthesis pathway in sweet potato,candidate genes(IbOS) of sweet potato were obtained by screening our sweet potato transcriptome data by domainblasting searching (Appendix F).TheIbOS1andIbOS2expression levels increased significantly following insect infestation (Fig.3-A).Because an established genetic transformation system for sweet potato is not available,a heterologous transient overexpression system was used to functionally characterizeIbOS1andIbOS2in tobacco plants.The resulting data suggested that the IbOS1 protein can induce the synthesis ofβ-ocimene andallo-ocimene in tobacco plants (Fig.3-B).IbOS1 was also localized in tobacco cell chloroplasts (Fig.3-B).Thus,allo-ocimene may be synthesized by the following previously unknown pathway: geranyl pyrophosphate(GPP)→β-ocimene→allo-ocimene.We then tested whether wounding and JA are involved in regulating the synthesis ofallo-ocimene,and found that both wounding and JA treatment induced the release ofallo-ocimene(Fig.3-C).TheIbOS1expression levels were regulated by both wounding and JA treatment (Fig.3-C;Appendix G).Therefore,mechanical injury activated the JA pathway to regulateIbOStranscription,ultimately leading to increasedallo-ocimene contents.

Fig.3 Effect of sweet potato weevils on the formation of allo-ocimene.A,elucidation of the biosynthetic pathway of allo-ocimene and effect of sweet potato weevil treatment on IbOSs expression.GPP,geranyl pyrophosphate;OS,ocimene synthase;0h,control group before sample preparation;CK-24h and CK-48h,control group of 24 and 48 h,respectively;SW-24h and SW-48h,sweet potato weevil treatment of 24 and 48 h,respectively.B,subcellular localization of the IbOS protein using protoplasts of Arabidopsis thaliana.C,effect of continuous wounding and jasmonic acid treatment on the release of allo-ocimene and IbOSs expression.CW,continuous wounding treatment group;JA,jasmonic acid treatment group.ND,not detected;Std,standard.All data are expressed as mean±SD (n=3).Significant differences between control and treatment groups are indicated (*,P≤0.05 and **,P≤0.01),as determined by the independent Student’s t-test.

allo-Ocimene is a monoterpene comprising two isoprene units.Monoterpenoids are mainly produced through the MEP pathway in plastids.Geraniol synthase catalyzes the conversion of GPP to geraniol,which is then converted to citral by an alcohol dehydrogenase (Chenet al.2019).Theallo-ocimene biosynthesis pathway in plants remains unclear,although a pathway involving citral has been hypothesized (Chenet al.2019).Because GPP can be directly converted toβ-ocimene by terpene synthases (TPSs) andallo-ocimene is structurally similar toβ-ocimene,we speculated thatallo-ocimene may be formed through the transformation ofβ-ocimene.In the present study,a large amount ofβ-ocimene was produced following the expression ofIbOS1.Meanwhile,allo-ocimene was released,which further suggested that it is synthesizedviaβ-ocimene.The expression ofTPSgenes is also regulated by the biological clock.For example,previous studies reported circadian rhythms in the expression of the laurene synthase and ocimene synthase genes inAntirrhinummajus(Plantaginaceae:Antirrhineae),as well as the ocimene synthase and myrcene synthase genes inA.thaliana,with high and low expression levels in the afternoon and at midnight,respectively (Luet al.2002;Chenet al.2003).Diurnal changes in the expression levels of these upstream regulatory genes may lead to the rhythmic release ofalloocimene,i.e.,high during the day and low at night.

JA is a typical injury-related hormone that accumulates rapidly in damaged tissues.As a second messenger,JA subsequently activates the production of protease inhibitors and toxic secondary metabolites.Earlier research has indicated that mechanical injury and JA treatments can induceallo-ocimene production in many plants,although the regulatory molecular mechanisms may differ (Chenet al.2019).The JA signaling pathway may promote the synthesis and release of terpenoids that activate the expression of genes in specific biosynthesis pathways.The TPS-encoding gene contributing to terpenoid synthesis is induced in a JA-dependent manner,and a mechanistic study has identified the core myelocytomatosis transcription factor in the JA pathway as a transcriptional regulator of theTPSgene (Rooset al.2015).Considered together,these findings at least partly explain whyz3HAC is released more rapidly than the monoterpenes.Green leaf volatiles and JA,which is produced within minutes,are synthesized almost simultaneously.In contrast,terpenoid synthesis and release are regulated by the transcription factor-mediated expression of terpenoid synthesis-related genes after JA is synthesized.

3.4.Treatments with z3HAC and allo-ocimene can significantly induce the defense-related activity of sweet potato shoots in response to sweet potato weevils

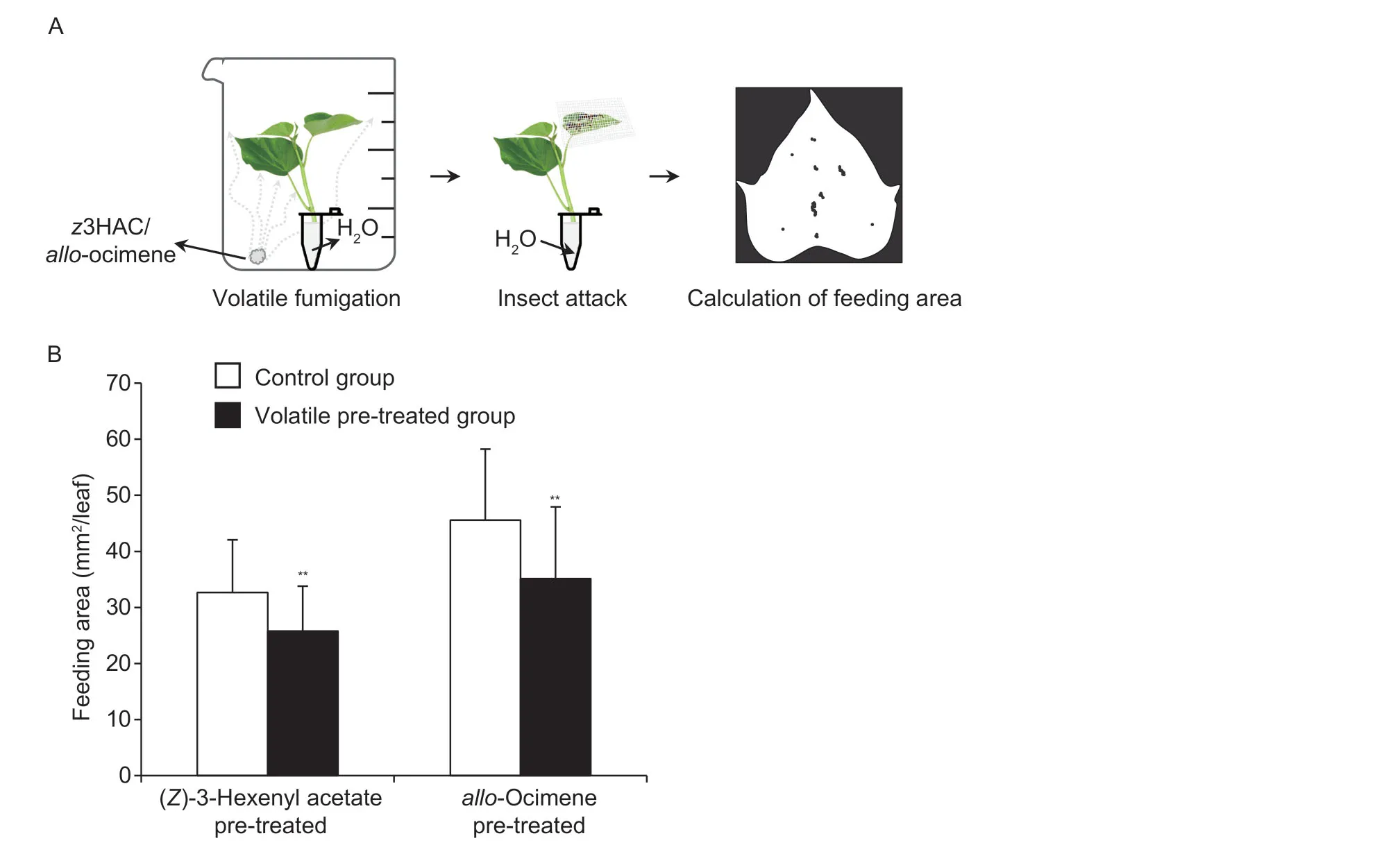

z3HAC andallo-ocimene,which are commonly released in various plants,have various anti-pest functions.Their rhythmic release suggests that they may be signaling molecules that mediate plant–plant communication.The insect resistance of the treated sweet potato shoots was assessed by evaluating the area of leaf damage (Fig.4-A).Thez3HAC andallo-ocimene pretreatments inhibited feeding by sweet potato weevils,implying that gaseousz3HAC andallo-ocimene can activate the anti-insect activity of healthy sweet potato leaves (Fig.4-B).

Fig.4 Effects of (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate (z3HAC) and alloocimene on sweet potato weevils.A and B,schematic and anti-herbivore activity assay of z3HAC and allo-ocimene pretreated sweet potato leaves against sweet potato weevils.All data are expressed as mean±SD (n=25).Significant differences between control and treatment groups are indicated (*,P≤0.05 and **,P≤0.01),as determined by the independent Student’s t-test.

Green leaf volatiles are important components of plant defense systems that mediate the plant–herbivore–natural enemy interaction,but they also serve as signals involved in communication between plants.A pretreatment withz3HAC reportedly enhanced the resistance of maize toSpodopteralittoralis(Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) (larval stage) by delaying the growth of this insect pest (Huet al.2019).(Z)-3-hexen-1-ol andz3HAC can also attract many natural enemies of insect pests,such as aphid parasitoids,predatory Miridae,and predatory mites.This compound is better known for mediating plant–plant signal transduction than for its other defense-related functions.Over the last decade,research interest has grown in plant–plant communication,especially in the role of volatile organic compounds as potential promoters of plant defense.Their signal transduction function implies that HIPVs can further activate the defensive system of the HIPV-producing plant,while also being recognized by neighboring plants,which are then somewhat protected against a possible insect infestation.The state of readiness caused by an external signaling molecule reflects a ‘priming defense’ (Zhanget al.2010).In this process,the signaling molecules do not confer resistance,but activate the defense responses of plants against the insect pests.The plant–plant signal transduction that induces defense activities mediated byz3HAC was first observed in maize (Liaoet al.2020),but has since been detected in rice,wheat,tomato,tobacco,pepper,and other crops.Hence,the underlying remote signaling pathway is common among plants in response to abiotic stresses such as mechanical damage and biotic stresses such as insect damage.Studies have also demonstrated that volatiles can mediate the signal transduction between different plant species.In the present study,z3HAC significantly protected sweet potato plants from sweet potato weevils,indicating that it may be useful for improving the prevention and control of sweet potato weevil infestations under field conditions.

Terpenes are synthesized by all plants and serve as plant hormones,protein modifiers,antioxidants,and inducers of plant defenses.Monoterpenes,terpenes with a simple structure,play an important role in many defense responses.For example,insect behavior experiments have revealed the strong avoidance effect ofβ-ocimene onEctropisobliqua(Lepidoptera: Geometridae) (Jinget al.2021b).Another study has confirmed thatβ-ocimene can attractAphidiuservi(Hymenoptera: Braconidae),a parasitic wasp that feeds on the aphids which are pests of broad beans (Takemoto and Takabayashi 2015).β-Ocimene also induces the substantial production of volatile compounds that protect healthy tomato plants from aphid infestations (Casconeet al.2015).In sweet potato,DMNT was reported to prime adjacent plants to increase their resistance to the larvae ofSpodopteraspecies (Meentset al.2019).Althoughallo-ocimene synthesis can be induced by insects in many plants,its defense-related functions have not been characterized as well as those ofβ-ocimene.Nevertheless,previous research has indicated that anallo-ocimene treatment can enhance the resistance ofA.thalianatoBotrytis cinerea(Teleomorph: Botryotinia fuckeliana) (Kishimotoet al.2006).Jooet al.(2018) have confirmed that when the rhythmic release cycle of sesquiterpenoids is synchronized with the peaks in the rhythmic behavior of parasites,its parasitism efficiency would increase.In the present study,we detected circadian changes in bothz3HAC andallo-ocimene levels during a continuous insect infestation and found thatz3HAC andallo-ocimene could increase the resistance of sweet potato plants to sweet potato weevilsviasignal transduction,but the specific mechanism mediating this resistance still requires more thorough elucidation.

3.5.Pretreatments with z3HAC and allo-ocimene can significantly induce defense-related metabolites in sweet potato shoots

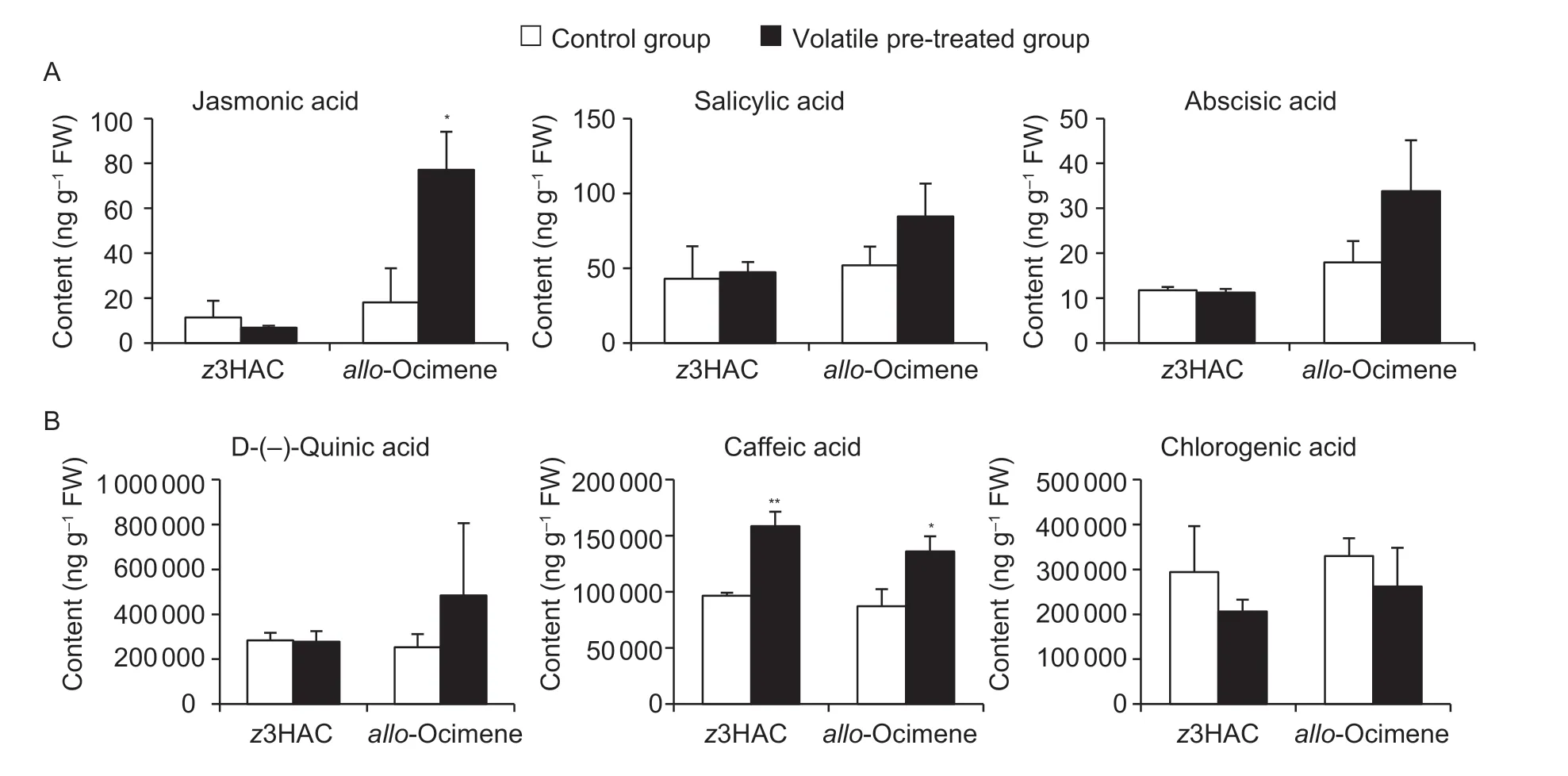

Bothz3HAC andallo-ocimene can protect sweet potato shoots from the sweet potato weevil through signal transduction.Plant defenses initiated by HIPVs usually involve JA and SA defense hormone regulatory signaling pathways.Thus,the phytohormone contents were measured in sweet potato shoots pretreated withz3HAC andallo-ocimene.The JA content increased followingallo-ocimene fumigation (Fig.5-A).Both pretreatments also increased the level of caffeic acid (Fig.5-B),the precursor of chlorogenic acid,which has been previously identified as a compound related to insect resistance in plants (Liaoet al.2020).

Fig.5 Effects of (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate (z3HAC) and allo-ocimene pretreatment on the neighboring sweet potato plants.A,phytohormones.B,phenolic acid.FW,fresh weight.All data are expressed as mean±SD (n=3).Significant differences between control and treatment groups are indicated (*,P≤0.05 and **,P≤0.01),as determined by the independent Student’s t-test.

Healthy plant tissues typically release only small amounts of GLVs and volatile terpenes,whereas the production of these compounds increases quickly after plant tissues are damaged by pathogens or herbivores(Zenget al.2019).These volatiles are transmitted as signaling molecules to distal plant parts,but are also perceived by neighboring plants,which then induce defense activities that provide protection from the pathogens and/or insect pests.During plant–plant communication,the cells in plants next to the plants that are exposed toz3HAC and sesquiterpenes undergo rapid membrane depolarization,which then activates a cascade of reactions in the host plant (Zebeloet al.2012).Although the gas-receptor proteins in plants have not yet been characterized,stable isotope tracers have confirmed that HIPVs can be absorbed by healthy plants to activate their systemic defenses.For example,a previous isotope tracing study proved that (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol can activate the synthesis of JA and the anti-insect metabolite,(Z)-3-hexen-1-ol glycoside,in tea plants (Dudarevaet al.2006).Other investigations have demonstrated thatz3HAC can promote JA accumulation and a co-treatment with indole can significantly enhance JA signaling (Engelberthet al.2004;Huet al.2019).Different combinations of volatiles will differentially affect defense activities.Accordingly,the combined effects of volatiles on various pathways should be studied.The induction of JA synthesis byz3HAC may be related to increases in the synthesis of the fatty acid precursor,linolenic acid (LNA),and the expression of genes encoding allene oxide synthase (AOS) and lipoxygenase 1 (LOX1) (Frostet al.2008).It has also been reported that the levels of JA in plants exposed toz3HAC were no different from those in the control plants,while jasmonoyl-isoleucine (JA-Ile) increased significantly(Jinget al.2021a).In the present study,the z3HAC pretreatment did not induce JA synthesis.This shows that JA-Ile may be another inducible plant signal,and thatz3HAC pretreatment may induce JA-Ile synthesis.As well as activating plant hormone signaling pathways,z3HAC can also induce the synthesis of other substances related to resistance in order to improve the plant’s defenses.In maize seedlings,az3HAC pretreatment increased the production of volatile sesquiterpenes associated with insect resistance in response to mechanical injury and caterpillar infestation (Liaoet al.2020).The combined effects ofz3HAC and indole were reported to promote the biosynthesis of benzoxazinoids,antibacterial metabolites in plants (Huet al.2019).z3HAC can also upregulate the expression of many defense genes inA.thaliana,such asAtCHS,AtDGK1,AtCOMT,AtGST1,andAtLOX2(Kishimotoet al.2006).Anallo-ocimene treatment can also modulate the expression of several defensive genes,such asAtCHS,AtDGK1,AtCOMT,AtGST1,andAtLOX2(Kishimotoet al.2006),while also activating the expression of relatedPRgenes downstream of the SA pathway inA.thaliana,which ultimately leads to enhanced resistance toB.cinerea(Kishimotoet al.2006;Chenet al.2019).

Phenolic acids play a vital role as antifeedants and toxins in plant chemical defenses.Our previous studies have found that chlorogenic acid is an important defensive secondary metabolite in sweet potato,and its level is increased by insect invasion (Liaoet al.2020).Chlorogenic acid is synthesized by the condensation of caffeic acid and D-(–)-quinic acid.In the present study,chlorogenic acid in sweet potato was not influenced byz3HAC orallo-ocimene,whereas caffeic acid,the essential precursor of chlorogenic acid,increased significantly,thus preparing the plant for the subsequent challenge.The present study has revealed thatalloocimene activated JA synthesis and caffeic acid accumulation,so it is a defense-related metabolite that protects plants from insect pests.These results suggest thatz3HAC andallo-ocimene released after insect infestation or mechanical injury activated the defense system of healthy sweet potato plants.

4.Conclusion

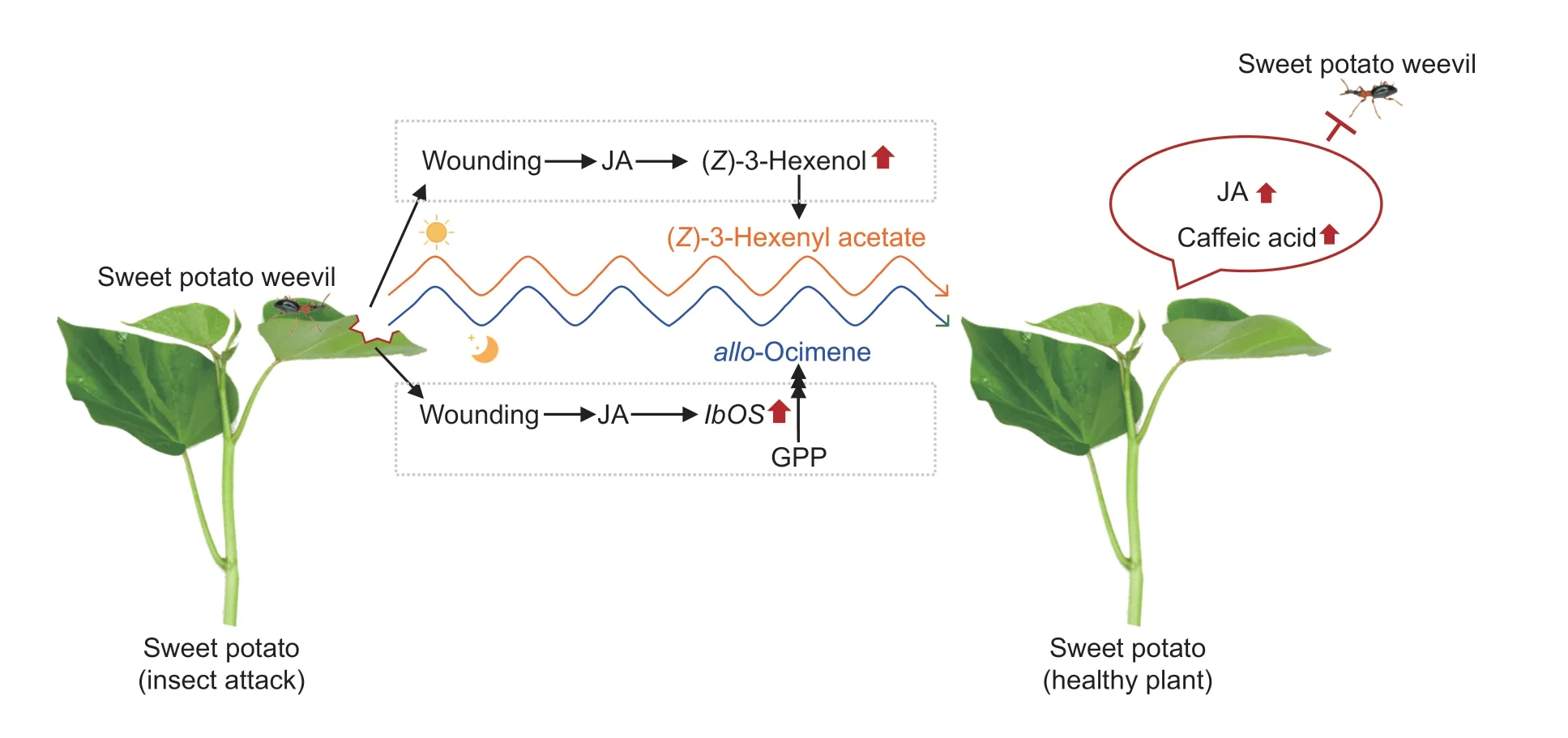

This study found that HIPVs mediate the communication between plants and the information exchange in the plant–herbivore–enemy system to protect plants from herbivorous insects.Two rhythmically-released volatiles,z3HAC andallo-ocimene,were identified in sweet potato.The synthesis ofz3HAC is regulated by the damage caused by insect feeding through the accumulation of the substrate (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol (Fig.6).Insect infestation regulates the transcription of a key gene (IbOS)viawounding and JA signaling pathways to promote the production ofallo-ocimene.Thez3HAC released can also act as a gaseous signaling molecule that increases the caffeic acid content to enhance the protective activities of neighboring sweet potato plants against sweet potato weevils.allo-Ocimene can also increase the JA and caffeic acid levels to improve the ability of plants to defend themselves against pests.The results of this study provide a theoretical basis for future research on the HIPVs of sweet potato,and may help to enable the development of new agronomic practices to prevent and control insect pests.

Fig.6 Schematic representation of (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate and allo-ocimene as mediators involved in priming the defense of sweet potato leaf.JA,jasmonic acid;IbOS,Ipomoea batatas ocimene synthase;GPP,geranyl pyrophosphate.Red arrows represent up-regulation.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China–Guangdong Natural Science Foundation Joint Project (U1701234).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendicesassociated with this paper are available on https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jia.2023.02.020

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年6期

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年6期

- Journal of Integrative Agriculture的其它文章

- ldentification of two novel linear epitopes on the p30 protein of African swine fever virus

- Uncertainty aversion and farmers’ innovative seed adoption:Evidence from a field experiment in rural China

- Ensemble learning prediction of soybean yields in China based on meteorological data

- Increasing nitrogen absorption and assimilation ability under mixed NO3– and NH4+ supply is a driver to promote growth of maize seedlings

- Significant reduction of ammonia emissions while increasing crop yields using the 4R nutrient stewardship in an intensive cropping system

- Maize straw application as an interlayer improves organic carbon and total nitrogen concentrations in the soil profile: A four-year experiment in a saline soil