Late sowing enhances lodging resistance of wheat plants by improving the biosynthesis and accumulation of lignin and cellulose

DONG Xiu-chun , QIAN Tai-feng CHU Jin-peng ZHANG Xiu LIU Yun-jing DAI Xing-long#, HE Ming-rong#

1 State Key Laboratory of Crop Biology, Ministry of Science and Technology/Key Laboratory of Crop Ecophysiology and Farming System, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs/Agronomy College, Shandong Agricultural University, Tai’an 271018, P.R.China 2 Jining Agricultural Technology Extension Center, Jining 272113, P.R.China

Abstract Delayed sowing mitigates lodging in wheat.However, the mechanism underlying the enhanced lodging resistance in wheat has yet to be fully elucidated.Field experiments were conducted to investigate the effects of sowing date on lignin and cellulose metabolism, stem morphological characteristics, lodging resistance, and grain yield.Seeds of Tainong 18,a winter wheat variety, were sown on October 8 (normal sowing) and October 22 (late sowing) during both of the 2015–2016 and 2016–2017 growing seasons.The results showed that late sowing enhanced the lodging resistance of wheat by improving the biosynthesis and accumulation of lignin and cellulose.Under late sowing, the expression levels of key genes (TaPAL, TaCCR, TaCOMT, TaCAD, and TaCesA1, 3, 4, 7, and 8) and enzyme activities (TaPAL and TaCAD) related to lignin and cellulose biosynthesis peaked 4–12 days earlier, and except for the TaPAL, TaCCR, and TaCesA1 genes and TaPAL, in most cases they were significantly higher than under normal sowing.As a result, lignin and cellulose accumulated quickly during the stem elongation stage.The mean and maximum accumulation rates of lignin and cellulose increased, the maximum accumulation contents of lignin and cellulose were higher, and the cellulose accumulation duration was prolonged.Consequently, the lignin/cellulose ratio and lignin content were increased from 0 day and the cellulose content was increased from 11 days after jointing onward.Our main finding is that the improved biosynthesis and accumulation of lignin and cellulose were responsible for increasing the stem-filling degree, breaking strength, and lodging resistance.The major functional genes enhancing lodging resistance in wheat that are induced by delayed sowing need to be determined.

Keywords: cellulose, late sowing, lignin, lodging resistance, wheat

1.Introduction

Winter wheat (TriticumaestivumL.) production in the North China Plain is threatened by wheat lodging (Fenget al.2019).Lodging increases pests and diseases, inhibits plant growth and development, and reduces the crop yield and quality (Ahmadet al.2020; Shahet al.2021).Lodging in winter wheat can be caused by improper management practices (e.g., high seeding rate and N input) and adverse environmental conditions (e.g., occurrence and quantity of rainfall and wind) (Niuet al.2016; Daiet al.2017; Ahmadet al.2018; Khobraet al.2019).Lodging can be reduced by decreasing plant height, but a reduction in plant height that is too great could reduce grain yield (Acreche and Slafer 2011; Wenget al.2017).Therefore, improving the physical strength of the basal stem has become the new research target for increasing crop lodging resistance, and thus grain yield.

Lignin and cellulose are the major cell wall components, and they provide stem mechanical strength and rigidity.Greater accumulation of lignin and cellulose in basal internodes promotes the lodging resistance of wheat, rice, maize, and buckwheat (Chenet al.2011; Konget al.2013; Zhang Jet al.2014; Zhanget al.2016, 2017; Wanget al.2015a, b; Ahmadet al.2021).Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (C4H), 4-coumarate:CoA ligase (4CL),p-coumarate 3-hydroxylase (C3H), hydroxycinnamoyl-CoA:shikimate hydroxycinnamoyl transferase (HCT), caffeoyl-CoAO-methyltransferase (CCoAOMT), cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR), caffeic acidO-methyltransferase (COMT), and cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD) play important roles in lignin biosynthesis (Weng and Chapple 2010; Vanholmeet al.2010).Lodging-resistant wheat varieties have a higher lignin content and higher activities of the PAL, 4CL, and CAD enzymes than other varieties (Penget al.2014; Kamranet al.2018; Huet al.2022).Moreover, the genesPAL,C4H,4CL,HCT,CCR,CAD, andCOMTare significantly positively correlated with the lignin content in wheat (Chenet al.2021; Yuet al.2021).Additionally, theCCR1,COMT, andCAD1gene expression levels and their corresponding enzyme activities are closely associated with stem lignin content and mechanical strength (Ma 2007).

The amount of cellulose per unit length of stem explains most of the variation in the stem mechanical strength of wheat (Appenzelleret al.2004; Zhanget al.2020).Cellulose is synthesized by cellulose synthase complexes (CSCs) in the plasma membrane (McFarlaneet al.2014).The cellulose synthases (CesAs), which act as the principal catalytic units of cellulose biosynthesis, are encoded by theCesAgenes that belong to a multigene family.For example, 10, 11, 13, 9, and 22CesAgenes have been reported inArabidopsis, rice, maize, barley, and wheat, respectively (Hamannet al.2004; Zhang Qet al.2014; Houstonet al.2015; Kauret al.2016).For cellulose synthesis in both primary and secondary cell walls, three distinct CesA proteins are required to form a functional CSC (Desprezet al.2007; Perssonet al.2007; Yeet al.2021).InArabidopsis, the primary wall CSCs typically include CesA1, CesA3, and CesA6-like subunits (CesAs 2,5, 6, and 9) (Desprezet al.2007; Perssonet al.2007; McFarlaneet al.2014), whereas the secondary wall CSCs consist of CesAs 4, 7, and 8 (Turneret al.2007).However, limited information on the relationship betweenCesAsgene expression and cellulose synthesis in wheat has been reported.

Several studies have shown that the late sowing of winter wheat can reduce lodging by affecting some morphological characteristics while maintaining a high yield (Daiet al.2017; Yinet al.2018).However, the manner in which lignin and cellulose biosynthesis and accumulation during stem development are influenced by the sowing date of winter wheat is not clear.Thus, the main objective of this study was to clarify the mechanism underlying the enhanced mechanical strength of wheat stems with delayed sowing by focusing on the biosynthesis and accumulation of lignin and cellulose during stem development.

2.Materials and methods

2.1.Plant materials, growth conditions, and experimental design

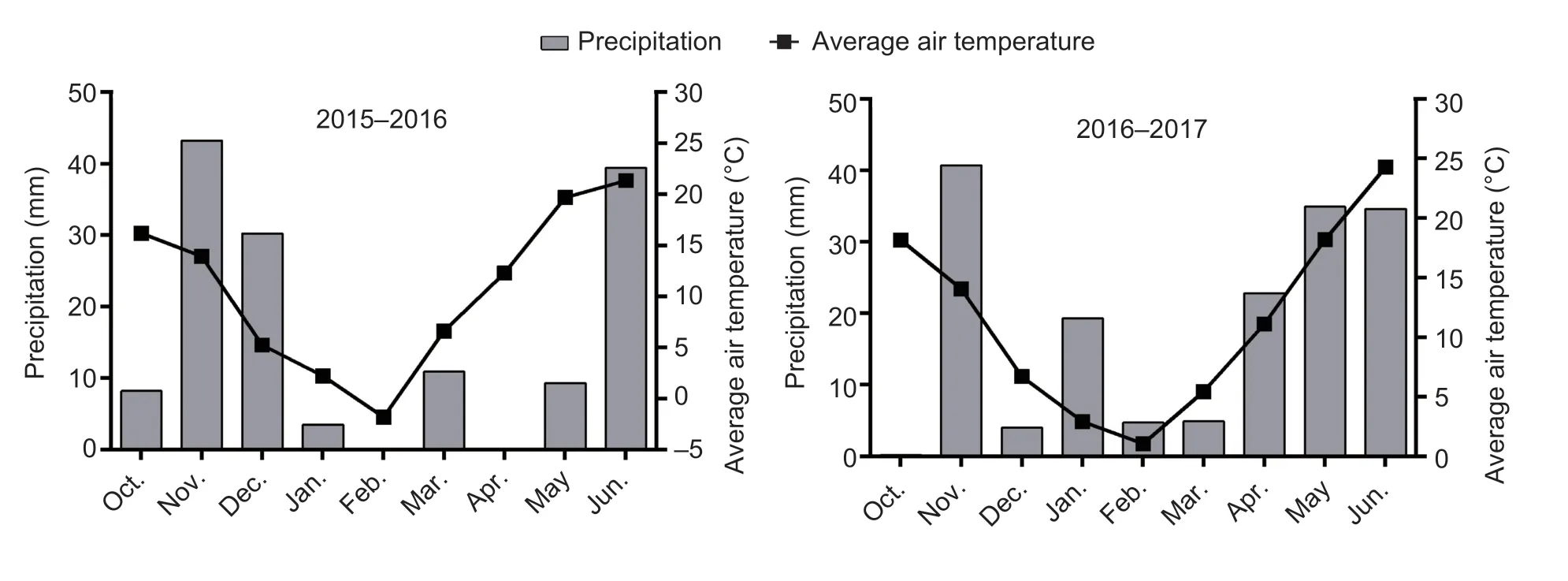

Tainong 18 (T18), a widely planted and lodging-resistant winter wheat cultivar, was grown in field trials in Dongwu Village (35°97′N, 117°06′E, Dawenkou, Daiyue District, Tai’an, Shandong Province, China) during the 2015–2016 and 2016–2017 growing seasons.Rainfall and temperature data were obtained from a meteorological station located <500 m from the experimental field (Fig.1).The soil was sandy loam, with a pH of 8.0.The contents of organic matter (Walkley and Black 1934), total nitrogen (N) (semi-micro Kjeldahl method; Yuen and Pollard 1953; Bremner 1960), available phosphorus (P) (Olsen method; Zandstra 1968), and available potassium (K; Dirks–Sheffer method; Melich 1953) in the 0–20 cm soil layer were 11.9 g kg?1, 1.1 g kg?1, 25.2 mg kg?1, and 46.8 mg kg?1during 2015–2016 and 12.1 g kg?1, 1.0 g kg?1, 25.3 mg kg?1, and 47.1 mg kg?1during 2016–2017, respectively.

Fig.1 Precipitation and average air temperatures over two growing seasons.

Seeds were sown with artificial single-grain precision at a density of 405 plants m–2using the meter rule.There were two sowing dates of October 8 (normal sowing) and October 22 (late sowing) in both 2015 and 2016.The accumulated temperature values (sum of daily average air temperature) before wintering of the two sowing treatments were 679.4 and 444.5°C d during the 2015–2016 growing season and 701.4 and 474.7°C d during the 2016–2017 growing season, respectively.

Treatments were arranged in a completely random design with three replicates.Each subplot was 30 m long and 3 m wide (12 rows spaced 25 cm apart).The previous crop in the planting areas was summer maize, and all straw and leaves were returned to the soil before tillage in both years.Basal fertilization of each subplot included N as urea, P as calcium superphosphate, and K as potassium chloride at rates of 120 kg N ha?1, 80 kg P2O5ha?1, and 120 kg K2O ha?1, respectively.An additional 120 kg ha?1of N was applied at the beginning of jointing.In both seasons, irrigation was carried out after sowing, before wintering, at jointing, and at anthesis (approximately 60 mm each time).Pests and diseases were controlled with chemicals as needed.No significant incidences of pests, diseases, or weeds occurred in any of the subplots.All subplots were harvested on June 13, 2016 and June 15, 2017.

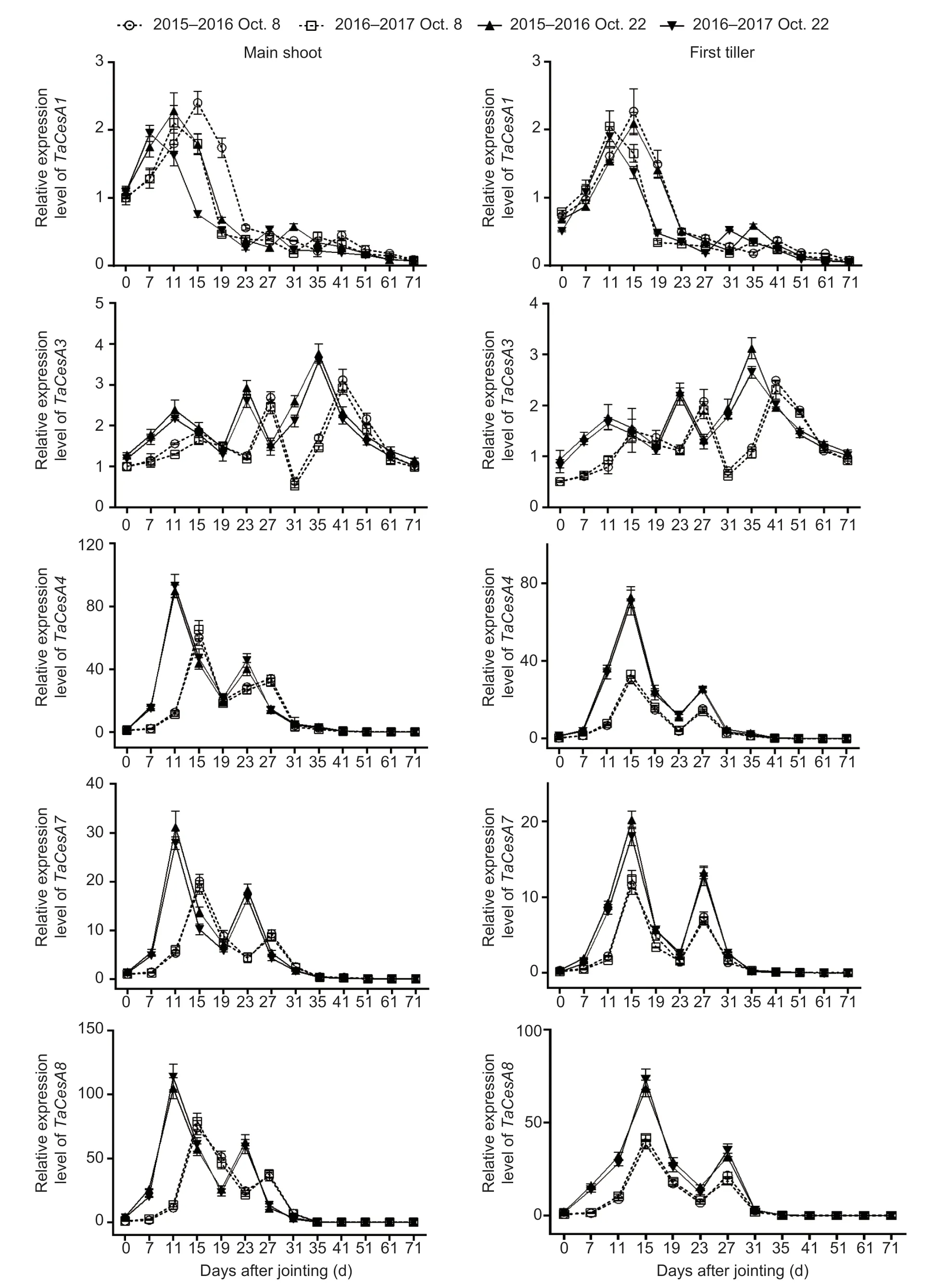

2.2.Enzyme activity and gene expression analyses

For lignin-related enzyme activity analysis, 10 basal second internodes (with leaf sheaths removed) of both main shoots and first tillers sown on October 8 and 22 in both 2015 and 2016, were selected at 10:00 a.m.at 7, 11, 15, 19, 23, 27, 31, 35, and 41 days after wheat jointing.For lignin and cellulose biosynthesis gene expression analysis, an additional 10 basal second internodes were selected at 10:00 a.m.at 0, 7, 11, 15, 19, 23, 27, 31, 35, 41, 51, 61, and 71 days after wheat jointing.We independently repeated this sampling three times to obtain three biological replicates of each treatment.An approximately 1.0-cm length of each middle internode was harvested, plunged directly into liquid nitrogen for at least 30 min, and then stored at –80°C until further analysis.

The TaPAL activity was determined according to Wanget al.(2015a, b), and the TaCAD activity was determined according to the method of Morrisonet al.(1994).The enzyme activities were expressed as U mg–1FW.

The total RNA from the wheat internode tissues was isolated using a Tiangen RNAprep Pure Plant kit (Beijing, China) and treated with DNaseI to remove any genomic DNA contamination.First-strand cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcriptase (TaKaRa, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.qRT-PCR was performed using the ABI SYBR?Select Master Mix Kit (4472908).The qRT-PCR protocol and the three-step thermal cycling protocol were performed following the manufacturers’ instructions as follows: pre-denaturation at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 50 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10 s, an annealing temperature of 60°C for 10 s, and an extension temperature of 72°C for 40 s.The relative expression levels were calculated with the equation 2???Ct.The housekeepingβ-actingene was used as the internal reference.Genes were obtained from the NCBI website.Each gene was tested using three technical replicates.The gene-specific primers are listed in Appendix A.

2.3.Lignin and cellulose contents of the basal second internode

Twenty basal second internodes (with leaf sheaths removed) of both main shoots and first tillers were collected randomly at 0, 7, 11, 15, 19, 23, 27, 31, 35, 38, 41, 46, 51, 56, 61, 66, and 76 days after wheat jointing in both 2016 and 2017.Samples were ovendried at 105°C for 30 min, then oven-dried at 70°C for 48 h, and finally milled into a fine power for the determination of the lignin and cellulose contents.Cell wall extracts were prepared according to Domonet al.(2013).Then, the cell wall material was isolated from 100 mg powder and digested with α-amylase, the lignin content of the dry cell wall was determined using the acetyl bromide method (Domonet al.2013), and the cellulose content was measured using the acetic/nitric acid method (Baldwinet al.2017).

2.4.Morphological characteristics of the basal second internode, lodging behavior, and grain yield

Plants were selected randomly from each plot, avoiding the outer two rows, and separated into main shoots and tillers.Ten main shoots and 10 first tillers were selected for lodging parameter measurements in both 2016 and 2017.Plant morphological characteristics of the basal second internode were measured at 0, 15, and 30 days after wheat heading, i.e., at the anthesis, middle grainfilling, and maturity stages, respectively.The length of the basal second internode was measured with a tape measure, and the culm breaking strength of the basal second internode was measured with a Stem Strength Tester (YYD-1; Zhejiang Top Instrument, Hangzhou, China).All separated samples were oven-dried at 105°C for 30 min and then oven-dried at 70°C to constant weight to estimate the dry weight.The internode dry weight per unit length of internode was defined as the filling degree (mg cm?1).

Plants were harvested from one 3.0 m2(2.0-m×6-row) quadrat in each subplot during both years.The grain was air-dried, weighed, and adjusted to a standard 12% moisture content (88% dry matter, kg ha?1).The time of lodging in each treatment was recorded when lodging first occurred.The lodging degree and lodging rate were assessed according to the methods of Hagiwaraet al.(1999) and Chenet al.(2011), respectively.

2.5.Simulation equations and parametric analysis

To estimate the accumulation characteristics of lignin and cellulose in wheat basal second internodes of the main shoots and first tillers after jointing, equations were simulated using the Software Curve Expert 2.0 based on the mean values of the two growing season dates (Appendices B and C).Polynomial regression equations (y=a+bx+cx2+dx3,y=a+bx+cx2+dx3+ex4, andy=a+bx+cx2+dx3+ex4+fx5) for the different stem stages were used to estimate the characteristics after jointing.All of the equations’ coefficients of determination (R2) were between 0.9588 and 1.0000.The first derivatives (y′) of the equations above arey′=b+2cx+3dx2,y′=b+2cx+3dx2+4ex3, andy′=b+2cx+3dx2+4ex3+5fx4, respectively.The second derivatives (y′′) of the above equations arey′′=2c+6dx,y′′=2c+6dx+12ex2, andy′′=2c+6dx+12ex2+20fx3, respectively.

When the first derivative equationy′ values of the lignin accumulation equation and cellulose accumulation equation are equal to or close to zero, the related solution value (x1–x4) is obtained, and these values are listed in Appendix D.Thex1 represents the initiating accumulation time of lignin or cellulose in each treatment.Thex2 is the number of days to reach the maximum accumulation content (Tw) after jointing of lignin or cellulose.Additionally, the (x2?x1+x3?x4) value is the accumulation duration time (T) of lignin or cellulose.The degradation duration (Td) of lignin and cellulose has the value (76?T?x1).Whenx1,x2,x3,x4, and 76 are introduced into their corresponding original equations, the values ofyobtained are the accumulation contents of lignin or cellulose, and are named W1, W2, W3, W4, and W5, respectively.Here, W2 represents the maximum accumulation content (W) of lignin or cellulose in each treatment.Furthermore, the ratio (W2–W1+W4–W3)/T represents the mean accumulation rate (V) of lignin or cellulose, and the ratio (W2–W3+W4–W5)/Tdis the mean degradation rate (Vd) of lignin or cellulose.

When the second derivative equationsy′′ of the lignin equation (2, 6, 9, and 13; and 5, 8, 12, and 15) and the cellulose equation (1, 19, 23, 26, and 27) are equal to zero, the solution value ofx5 is the number of days required to reach the maximum accumulation rate (Tm) of lignin or cellulose, andx6 is the number of days required to reach the maximum degradation rate (Tdm) of lignin or cellulose (Appendix D).Whenx5 andx6 are introduced into the corresponding first derivative equation, the attained valuey′ is the maximum accumulation rate (Vmax) and the maximum degradation rate (Vdm) of lignin or cellulose, respectively.

2.6.Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed with PASW ver.18.0.The experimental data for each sampling stage were analyzed separately.The treatment means were compared using the least significant difference (LSD) test atP<0.05 andP<0.01.The lignin and cellulose accumulation profiles were described by simulated equations for further mathematical analyses.Pearson’s correlations were obtained to determine the relationships among stem-filling degree and breaking strength, lignin and cellulose contents, gene expression levels and enzyme activities, and the mathematical parameters related to lignin and cellulose accumulation in wheat.

3.Results

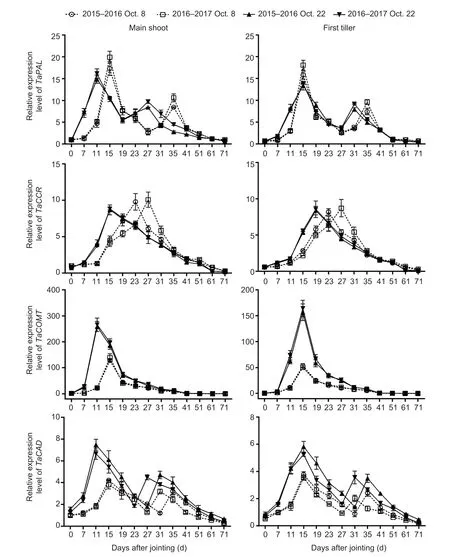

3.1.Expression of genes and activities of enzymes related to lignin biosynthesis

Sowing dates had a significant effect on the expression of genes and activities of enzymes related to lignin biosynthesis in wheat stems (Fig.2; Appendix E).No significant interactions of these parameters were observed between sowing date and year.During stem development, two peaks ofTaPALandTaCADand their related enzymes, and one expression peak ofTaCCRandTaCOMTwere observed in both main shoots and first tillers.From 41 days after jointing onward, the expression levels of the four genes were low, or even null.Moreover, the expression levels of the four genes and activities of the two enzymes mentioned above peaked 4–12 days earlier under late sowing than under normal sowing.Compared to those in the normal-sown wheat plants, the expression levels ofTaCOMTandTaCADwere significantly upregulated at almost all sampling times after jointing in the late-sown wheat plants, but the increasedTaPALandTaCCRlevels in late sowing were observed only at some young stem stages between 7 and 31 days after jointing.Similarly, the activity of TaCAD, but not TaPAL, was obviously increased by late sowing (Fig.3; Appendix E).The TaCAD activity increased on average by 32.87% in the main shoots and by 28.92% in the first tillers, across stem development for the two growing seasons.

Fig.2 Effects of sowing dates on the expression profiles of lignin biosynthetic genes of winter wheat in the 2015–2016 and 2016–2017 growing seasons.Bars mean SD (n=3).

Fig.3 Effects of sowing dates on the activities of lignin biosynthetic enzymes of winter wheat in the 2015–2016 and 2016–2017 growing seasons.Bars mean SD (n=3).

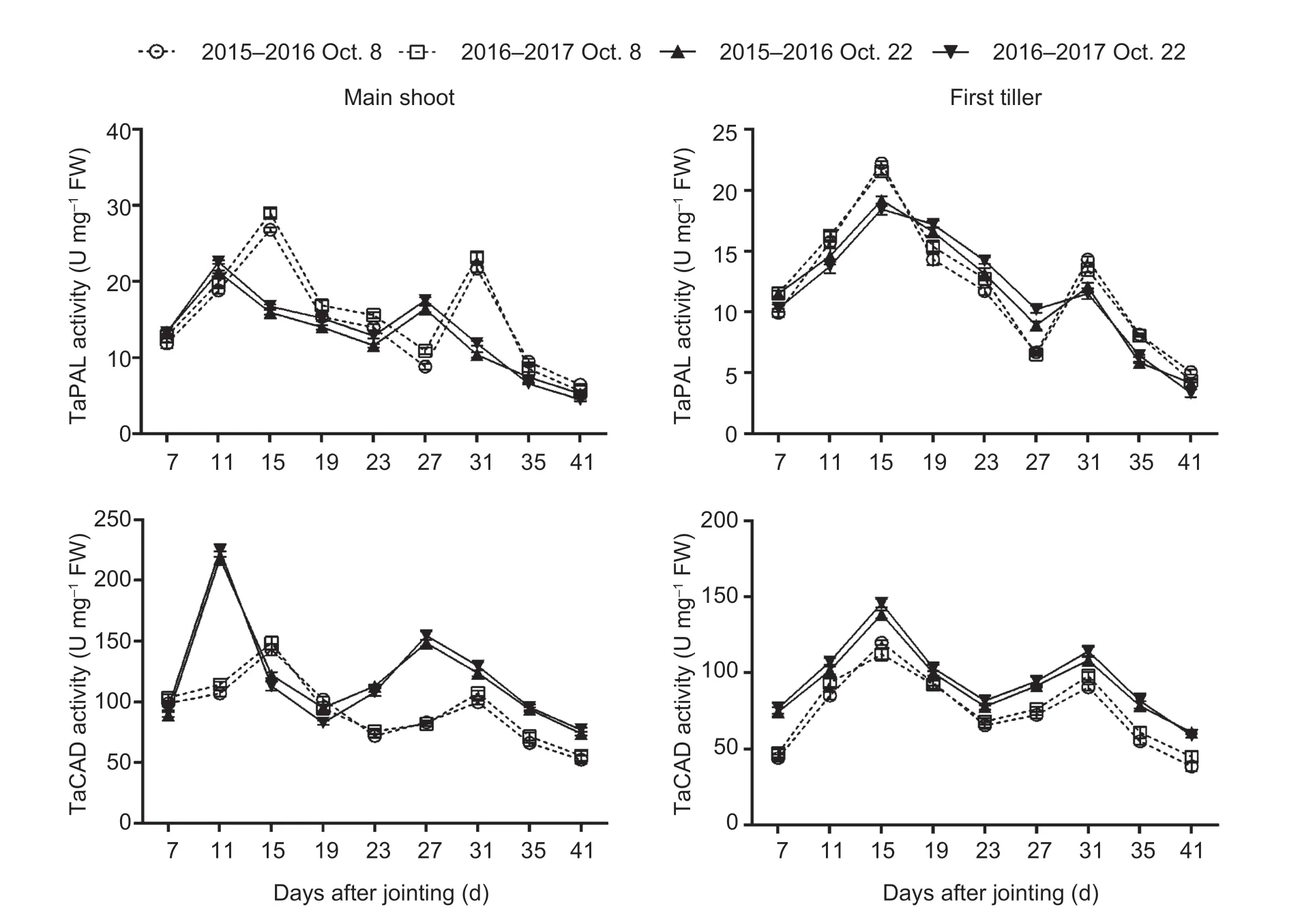

3.2.Expression of genes related to cellulose biosynthesis

Compared to those in the normal-sown wheat, the expression of genes related to cellulose biosynthesis was upregulated with delayed sowing (Fig.4; Appendix E).No significant interactions of these parameters were observed between sowing date and year (Appendix F).Under late sowing, theTaCesA4,7, and8expression levels were upregulated more obviously than those ofTaCesA1and3.The expression levels of genesTaCesA3,4,7, and8were increased on average by 49.62, 107.29, 117.10, and 171.08% (means of main shoots and first tillers after jointing of the two growing seasons), respectively.However, the expression level of geneTaCesA1remained unchanged under late sowing, and it was not expressed from 19 days after jointing onward.Interestingly,TaCesA4,7, and8were seemingly co-expressed with one another, as their expression peaks appeared at the same time.In addition, the expression levels of the five genes mentioned above generally peaked 4 days early under late sowing relative to the normal sowing date.

Fig.4 Effects of sowing dates on the expression profiles of cellulose biosynthetic genes of winter wheat in the 2015–2016 and 2016–2017 growing seasons.Bars mean SD (n=3).

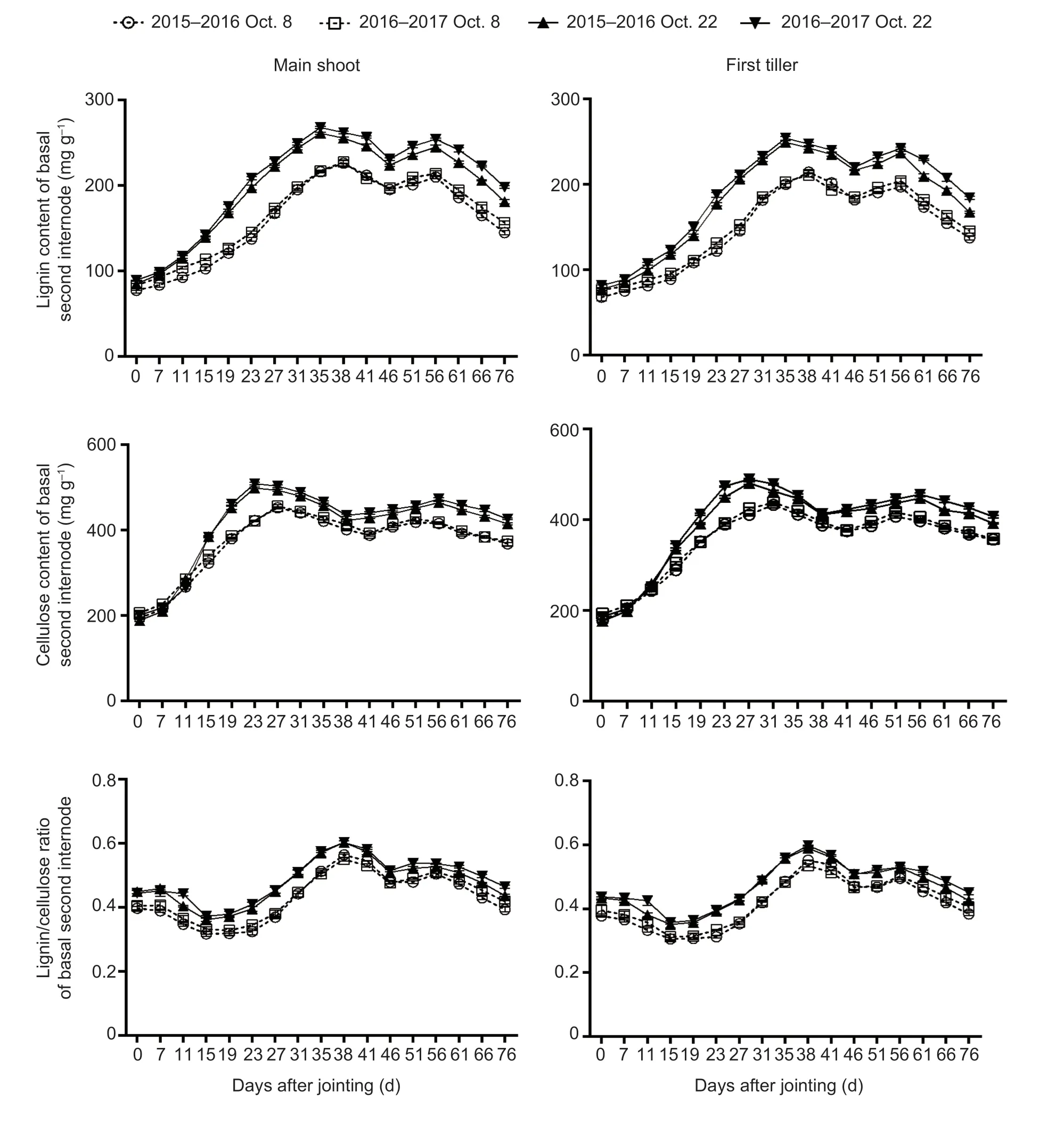

3.3.Accumulation dynamics of lignin and cellulose

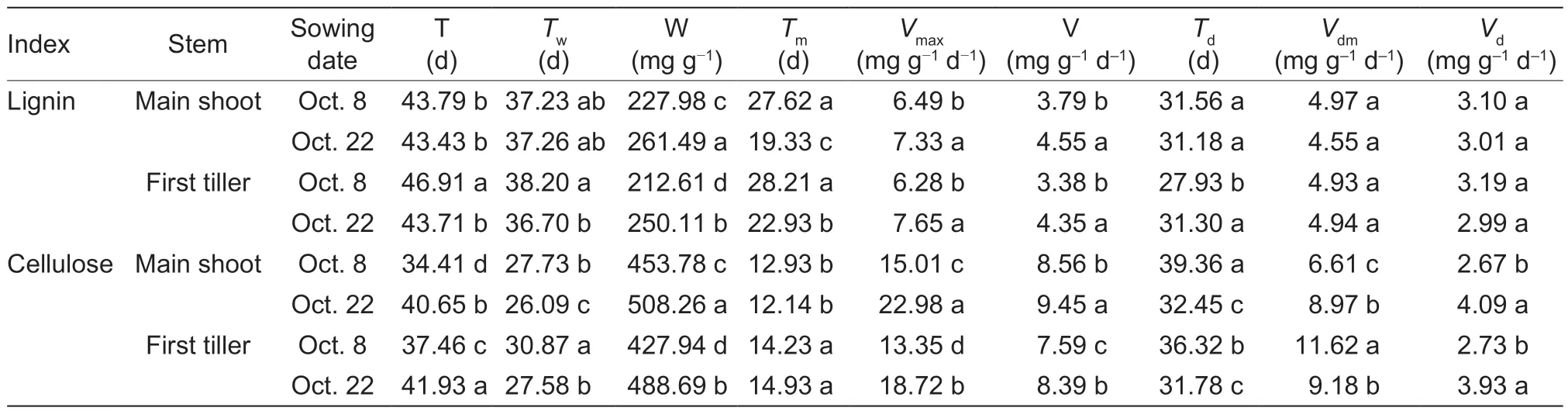

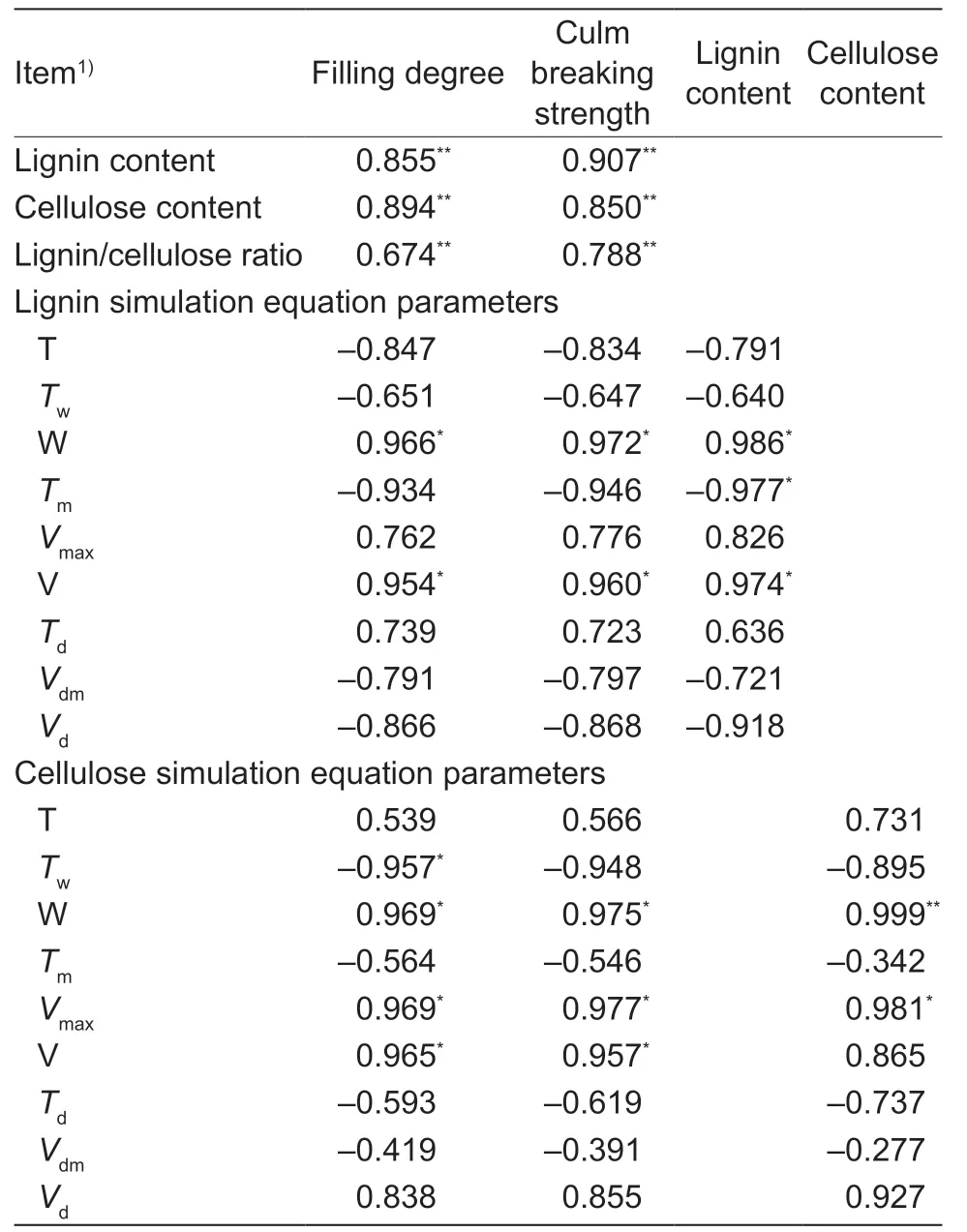

Compared to the normal-sown wheat plants, late sowing increased W,Vmax, and V of lignin by averages of 16.17, 17.43, and 24.43%, respectively (means of main shoots and first tillers).The corresponding increases for cellulose were 13.10, 46.65, and 10.48%, respectively (Table 1).VdmandVdof cellulose in main shoots/first tillers had similar upward trends under late sowing.Furthermore, under late sowing, T of cellulose was prolonged, while the time to reachTwof cellulose, time to reachTmof lignin, andTdof cellulose were shortened (Table 1).

No significant interactions of these parameters were observed between sowing date and year.Late sowing increased the lignin and cellulose contents and the lignin/cellulose ratio by averages of 23.46, 11.74, and 12.63%, respectively, compared with normal sowing (means of main shoots and first tillers after jointing for the two growing seasons) (Fig.5; Appendix F).

Fig.5 The dynamic accumulation of lignin and cellulose of winter wheat after jointing in the 2015–2016 and 2016–2017 growing seasons.Bars mean SD (n=3).

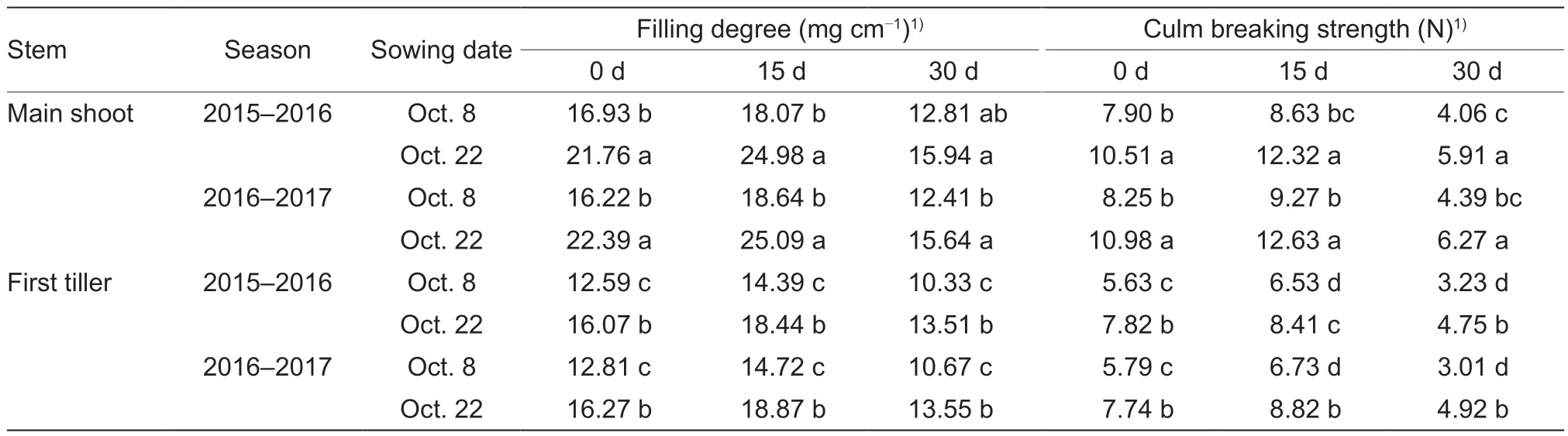

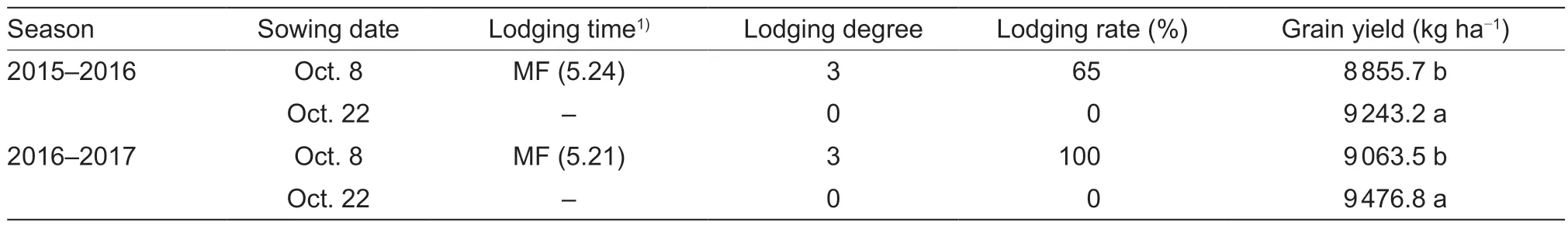

3.4.Filling degree and breaking strength of stems, lodging behavior, and yield

Compared with normal sowing, late sowing increased the filling degree and breaking strength on average by 31.65 and 38.92% in the main shoots, and by 28.13 and 40.49% in the first tillers, respectively, after heading in the two growing seasons (Table 2).No significant interactions of these parameters were observed between sowing date and year (Appendix F).Moreover, sowing dates had significant effects on both lodging behavior and grain yield (Table 3; Appendix F).No lodging occurred under late sowing in the two growing seasons.However, under normal sowing in the two years, serious lodging occurred at the middle grain-filling stage, with a lodging degree of 3 and lodging rates of 65% in 2016 and 100% in 2017.Finally, the late-sown crops had higher grain yields of more than 9 000 kg ha–1in both seasons.

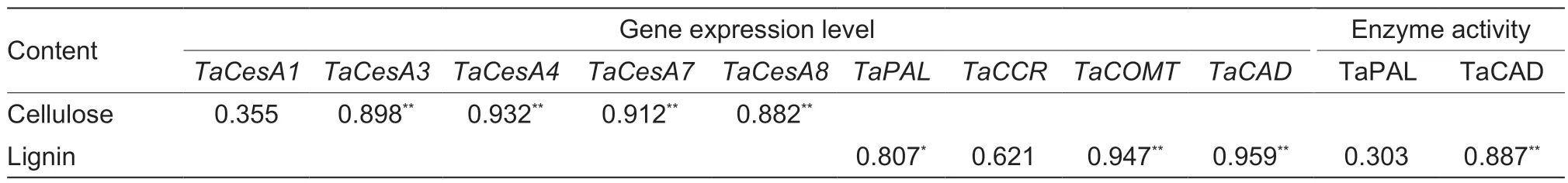

3.5.Correlation analysis

The lignin content was positively correlated with theTaPAL,TaCOMT, andTaCADexpression levels and TaCAD activity, while the cellulose content was positively correlated with theTaCesA3,4,7, and 8 expression levels during the wheat stem elongating stages (Table 4).The lignin and cellulose contents and the lignin/cellulose ratio after heading were positively and significantly correlated with the filling degree and breaking strength of basal second internodes (Table 5).Moreover, the simulation equation parameters W and V of lignin were significantly positively correlated with filling degree, breaking strength, and lignin content.The simulation equation parameters W andVmaxof cellulose were significantly positively correlated with filling degree, breaking strength, and cellulose content (Table 5).Similar correlations were found between theTwand V of cellulose and filling degree, and between the cellulose V and breaking strength (Table 5).However, no significant correlations were observed among parametersTd,Vdm, andVdwith both lignin and cellulose, filling degree, breaking strength, or lignin (or cellulose) content.

4.Discussion

4.1.Late sowing produced a high grain yield and enhanced the mechanical strength of wheat stems by increasing the accumulation of lignin and cellulose

The sowing dates have significant effects on stem lodging in wheat (Khobraet al.2019; Peakeet al.2020).Late sowing of wheat is an effective cultivation practice for enhancing lodging resistance without sacrificing grain yield (Daiet al.2017; Yinet al.2018).Sowing only 2 weeks late can reduce the threat of lodging in wheat byup to 30% (Spinket al.2005).Consistent with previous studies, we found that the lodging resistance of wheat improved with late sowing, while a high grain yield was observed (Table 3).

Table 1 Effects of sowing date on the parameters of lignin and cellulose accumulation of winter wheat1)

The lignin and cellulose contents are positively associated with the stem bending stress and lodging resistance, and greater lignin accumulation can increase the stem breaking strength in wheat (Konget al.2013; Zhang Jet al.2014; Zhenget al.2017; Khobraet al.2019).In maize, most of the variation in the mechanical strength can be explained by the cellulose amount per unit length of stem (Appenzelleret al.2004).Zhanget al.(2020) demonstrated that the higher the lignin and cellulose contents, the stronger the lodging resistance in oats.

In this study, late sowing significantly increased the stem lignin and cellulose contents and the lignin/cellulose ratio in most phases after wheat jointing (Fig.5).Significant positive correlations were also observedbetween lignin content, cellulose content, lignin/cellulose ratio, and the filling degree, and culm breaking strength (Fig.5; Table 5).Furthermore, the simulation and correlation analysis results showed that the obviously upregulated lignin accumulationviahigher W and V, and the upregulated cellulose accumulationviahigher W,Vmax, and V could explain the variations in both filling degree and culm breaking strength for late-sown crops (Tables 1 and 5).Hence, it is reasonable to propose that the higher stem-filling degree of wheat under late sowing is mainly due to greater and more rapid accumulation of dry matter, lignin, and cellulose, which in turn increase the culm bending strength and thus improve stem lodging resistance.

Table 2 Effects of sowing dates on the filling degree and culm breaking strength of the basal second internode of winter wheat over the two growing seasons

Table 3 Effects of sowing dates on the lodging behavior and grain yield of winter wheat during the two growing seasons

Table 4 Correlation analyses between lignin accumulation and related gene expression levels, and enzyme activities; and between cellulose accumulation and related gene expression levels on average during the stem elongation stages of wheat

4.2.Late sowing promoted lignin biosynthesis

The lignin-related enzyme activities of PAL, 4-CL, CCR, COMT, and CAD are significantly associated with the lignin content in wheat stems, and are closely associated with culm rigidity and lodging resistance (Ma and Luo 2015; Wanget al.2015a; Kamranet al.2018; Chenet al.2021).Moreover, the greater expression levels of thePAL,CCoAOMT,CCR,COMT, andCADgenes increased stem lignin accumulation and mechanical tissue strength, which in turn enhanced stem strength against lodging (Konget al.2013; Wanget al.2018; Liet al.2021).In our study, the lignin content was significantly positively correlated withTaPAL,TaCOMT, andTaCADgene expression and TaCAD enzyme activity, but was not significantly correlated with theTaCCRlevel or TaPAL activity in wheat stems (Table 4).These results demonstrate that the increased lignin accumulation promoted by late sowing was attributable to higher expression levels of the genesTaPAL,TaCOMT, andTaCAD, and the enzyme activity of TaCAD (Figs.2 and 3; Appendix E).Late sowing seemed to mainly regulate the downstream genes related to lignin biosynthesis,and thus their related enzyme activities, to increase lignin accumulation, but further study is still needed.In comparison, in the young wheat stem, delayed sowing markedly increased the TaPAL activity of main shoots at 7, 11, and 27 days, and increased theTaCCRlevels of both main shoots and first tillers at 7 to 19 days after jointing (Figs.2 and 3).These findings support the hypothesis that higher TaPAL activity andTaCCRlevels in some early stages of the stem might be sufficient for accelerating the next step of lignin biosynthesis, which then promotes lignin accumulation in later stem stages.

Table 5 Correlation analyses between the accumulation of lignin and cellulose, and either stem filling degree or culm breaking strength of winter wheat

Furthermore, consistent with previous studies, theTaPAL,TaCCR,TaCAD, andTaCOMTgenes studied here were mainly involved in the early stages of wheat stem maturity (Biet al.2011; Ma and Luo 2015) and showed low expression levels in the later stages (Liet al.2021), especially after heading, when the lignin content (Zhenget al.2017), as well as PAL (Wanget al.2015a), and CAD enzyme activities (Penget al.2014; Kamranet al.2018), reached their maximum levels in the latest maturity stages.We also found that the parametersTd,Vdm, andVd, which are related to lignin degradation, had no significant correlations with lignin content (Table 5).These results may explain the lignin accumulation characteristics.First, they explain the more rapid accumulation of lignin in young wheat stem, where greater gene expression occurred (Liet al.2021).Second, even though the mRNA levels and enzyme activity decrease during the later stages of stem development, lignin is accumulated progressively (Ma 2007; Liet al.2021).Once lignin is deposited in plant tissues, it is not converted or degraded until there is insufficient carbon and other metabolites at the latest maturity stages.Additionally, our results implied that the shortened ligninTmvalue in the late-sown crop was due to the advanced peaks (by 4 to 12 days) ofTaPAL,TaCCR,TaCAD, andTaCOMTexpression and TaCAD activity (Figs.2 and 3).

4.3.Late sowing promoted cellulose biosynthesis

Recently, 22CesAgenes related to cellulose biosynthesis were reported in hexaploid wheat (Kauret al.2016), but their expression patterns as regulated by sowing date have not been investigated.Previous studies indicated that gene group one (OsCesA1,3, and8) and gene group two (OsCesA4,7, and9) in the rice stem encode the components of primary and secondary cell wall cellulose biosynthesis, respectively (Tanakaet al.2003; Wanget al.2010; Kotakeet al.2011; Yeet al.2021).In the present study, we found that the measured gene groups of (TaCesA1and3) and (TaCesA4,7, and8), which are responsible for primary and secondary cell wall cellulose biosynthesis, respectively, were mainly expressed in young stem (Fig.4).This is similar to the expression pattern of genes related to lignin biosynthesis, and it corresponds with higher cellulose accumulation rates in the stem elongation stages.

Mutations in genesOsCesA4,7, and9have been found to decrease cellulose accumulation and mechanical strength (Kotakeet al.2011).However, Wuet al.(2017) pointed out that the reduction in cellulose accumulation was due to downregulation of the genesOsCesA1,3, and8under shaded treatment in rice; and a similar result was observed in cotton (Chenet al.2014).In this study, the second gene group (TaCesA4,7, and8) plusTaCesA3of the first gene group were significantly positively correlated with cellulose accumulation in wheat steam, and these four genes were upregulated under late sowing (Fig.4; Table 4; Appendix E).Interestingly, the identical expression patterns ofTaCesA4,7, and8, which are homologous to riceOsCesA7,4, and9, respectively, suggested that they might be co-expressed and could form a complex, as in rice, to play a role in regulating cellulose biosynthesis (Kotakeet al.2011; Kauret al.2016; Yeet al.2021).Further in-depth study is needed to examine this possibility.Moreover, the second gene group in this study had a higher expression level than the first gene group, which is consistent with the case of the two gene groups in maize (i.e.,ZmCesA10,11, and13;ZmCesA2,5, and7) (Zhang Qet al.2014).Taken together, these findings indicate that cellulose accumulation was promoted not only by increased expression of theTaCesA3,4,7, and8genes, but also by earlier peaks (by 4 days) in the expression of the two gene groups under the late sowing condition (Fig.4).To some degree, a similar regulatory mechanism may underlie the accumulation of cellulose and lignin under late sowing, but this topic requires further study.

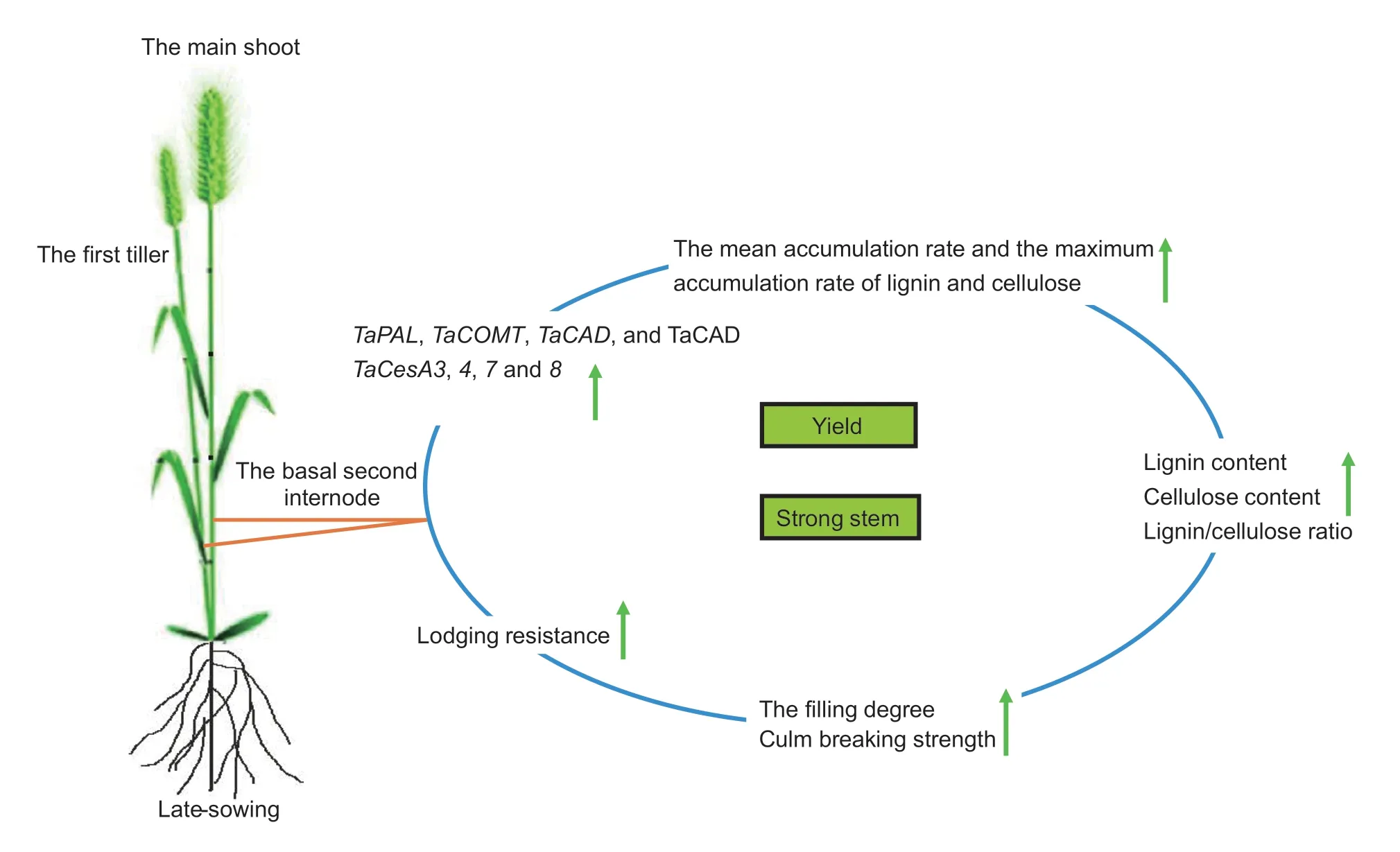

5.Conclusion

In response to delayed sowing, the accelerated and upregulated expression of key lignin and celluloserelated genes and enzyme activities together promoted the biosynthesis of lignin and cellulose and increased their accumulation.As a result, the higher lignin content, cellulose content, and lignin/cellulose ratio of the basal second internodes of late-sown wheat plants strengthened the stem-filling degree and breaking strength, and enhanced lodging resistance after heading, while a high grain yield was still obtained.The hypothesized mechanism by which late sowing enhances lodging resistance was shown in Fig.6.Future RNASeq transcriptome, proteomics, and protein interaction studies should be undertaken to reveal more of the details and deepen our understanding of the benefits of delayed sowing in wheat.

Fig.6 The hypothetical mechanism of the late-sowing enhancement of lodging resistance in winter wheat by lignin and cellulose biosynthesis.Green arrows represent the increasing trends.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0300403), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31801298) and the Fund of Shandong ‘Double Top’ Program, China (SYL2017YSTD05).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendicesassociated with this paper are available on https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jia.2022.08.024

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年5期

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年5期

- Journal of Integrative Agriculture的其它文章

- Herbicidal activity and biochemical characteristics of the botanical drupacine against Amaranthus retroflexus L.

- Developing a duplex ARMS-qPCR method to differentiate genotype l and ll African swine fever viruses based on their B646L genes

- The effects of maltodextrin/starch in soy protein isolate–wheat gluten on the thermal stability of high-moisture extrudates

- Elucidation of the structure, antioxidant, and interfacial properties of flaxseed proteins tailored by microwave treatment

- Effects of planting patterns plastic film mulching on soil temperature, moisture, functional bacteria and yield of winter wheat in the Loess Plateau of China

- lnversion tillage with straw incorporation affects the patterns of soil microbial co-occurrence and multi-nutrient cycling in a Hapli-Udic Cambisol