The effects of maltodextrin/starch in soy protein isolate–wheat gluten on the thermal stability of high-moisture extrudates

XlE Si-han, WANG Zhao-jun, HE Zhi-yong, , ZENG Mao-mao, , QlN Fang, , Benu ADHlKARl, CHEN Jie, #

1 State Key Laboratory of Food Science and Technology, Jiangnan University, Wuxi 214122, P.R.China

2 Collaborative Innovation Center of Food Safety and Quality Control, Jiangnan University, Wuxi 214122, P.R.China

3 Analysis Centre, Jiangnan University, Wuxi 214122, P.R.China

4 School of Science, RMIT University, Melbourne, VIC 3083, Australia

Abstract This study aimed to investigate the interaction between maltodextrin/starch of different molecular weight distributions and soy protein isolate (SPI)–wheat gluten (WG) matrix during high-moisture extrusion.Two maltodextrins (dextrose equivalent (DE): 10 and 20) and wheat starch were extruded with SPI–WG blend in a system of 65, 70, and 75% moisture to investigate their effects on texture and thermal stability.Incorporating 5% maltodextrin (DE10) in the SPI–WG matrix improved the fiber structure and thermal stability.When wheat starch was thoroughly gelatinized during subsequent sterilization, the fiber structure and thermal stability were also improved.It was found that the plasticization caused by small-molecular weight saccharides and enhanced phase separation caused by large-molecular weight saccharides changed the melting temperature of blends and significantly improved the texture and thermal stability of extrudates.

Keywords: high-moisture extrusion, protein, saccharide, fiber structure, textural properties, rheology, plasticization, phase separation

1.lntroduction

Traditional meat consumption comes with a higher environmental footprint as meat production is a resourceintense process (Aiking and de Boer 2020).Meat analogs are gaining popularity due to their high protein content, and their production is much less resource-intence and thus comes with eco-friendliness (Hoeket al.2011).Meat analogs can be produced using both low- and highmoisture extrusion processes.The extrudates produced with the latter have received special attention due to their ready-to-eat potential, improved fibrous structure, and less energy-intense properties (Aroraet al.2020; Zhanget al.2022).Generally speaking, thermal treatments, such as commercial sterilization or pasteurization, are necessary for extrudates for a longer duration of storage.However, thermal treatments may cause texture degradation, damage to the fibrous structure, or even the disappearance of the fibrous structure (Samardet al.2019).Based on our knowledge, only few studies were conducted on the thermal stability of extrudates.

Theories explaining the fiber formation during highmoisture extrusion cooking have been proposed based on biopolymer incompatibility and phase separation into the multiphase system (Yuryevet al.1991; Schmittet al.1998; Cornetet al.2022).The followings are several types of phase separation reported in the high-moisture extrusion process.Sandoval Murilloet al.(2019) reported the formation of water-rich and -deficient domains in pea protein extrudates.Moreover, phase separation of insoluble ingredients and soluble saccharides was reported (Yuryevet al.1991; Tolstoguzov 1993; Grinberg and Tolstoguzov 1997).Soluble or insoluble domains can also be obtained through complex coacervation or associative phase separation, which is caused by weak attractive and nonspecific interactions among biopolymers (Van der Waals, electrostatic, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic interactions) (Piculellet al.1995; Imesonet al.1977).Shear-induced phase deformation and phase alignment also promote fiber formation (Tolstoguzov 1993), which is facilitated by velocity and viscosity gradients due to laminar flow during the cooling stage (Cheftelet al.1992; Akdogan 1999).

According to the glassy-rubbery-viscous state theory, reducing molecular mobility can help to stabilize the structure of polymer materials after thermal treatment (Sladeet al.1991).Below the glass transition temperature (Tg), macromolecules are relatively stable because all segments have extremely high rigidity (Levine and Slade 1988).At temperatures higher than the melting temperature (Tm), macromolecules enter a viscous flow state, in which segments and molecules become active, resulting in textural weakening and structural changes (Goffet al.1993; Roos 1995).Therefore, we hypothesized that the weakening of extrudates or disappearance of the fibrous structure after heating is related to increased molecular flexibility and fluidity at high temperatures.

Many studies have shown that adding reactive molecules or plasticizers (e.g., saccharides) into protein materials can improve textural and structural properties by strengthening covalent bonds and noncovalent interactions.Budhavaramet al.(2010) reported that modifying ovalbumin with nucleophilic addition reaction reduced Tgand/or increased thermal stability.An increase in hydrophobic linear substituents reduced Tg, while an increase in hydrophilic and cyclic substituents increased thermal stability without changing Tg.Tianet al.(2009) reported that soy protein plastics containing triethanolamine had higher thermal stability and mechanical properties.Matthey and Hanna (1997) also reported that significant interactions between amylose and whey protein concentrate reduced the molecular degradation of starch.

Although adding starch/maltodextrin can influence rheological properties and fiber formation during extrusion, it is unclear which structural and reactive properties of saccharides are directly related to imparting thermal stability and fiber formation.The molecular weight distribution of saccharides, their concentration in the formulation, and extrusion conditions are all important in protein–saccharide and protein–protein interactions.Allenet al.(2007) found a covalent complex formed between amylose and whey protein in an extrusion-expansion product was responsible for reducing the water-holding capacity of starch and proteins; interestingly, there was little interaction between pregelatinized waxy starch and the protein under the same extrusion condition.According to Chenet al.(2021), adding amylopectin to pea protein isolate during high-moisture extrusion (58%, w/w) promoted anisotropic structure formation and improved fibrous degree, whereas the addition of amylose did not affect the fibrous degree.Martinet al.(2021) found that changes in protein solubility after extrusion were related to the type and rheological properties of starch rather than the molecular interaction between starches and rapeseed proteins.However, the impact of the molecular weight distribution of saccharides on the formation of fiber structure and thermal stability in extruded meat analogs is still unknown.

This study examines the interaction between starch/maltodextrin of different molecular weight distributions and soy protein isolate (SPI)–wheat gluten (WG) matrix during high-moisture extrusion and its effect on the thermal stability of extrudates.Based on the results of preliminary experiments, two maltodextrins with different molecular weights and wheat starch were selected.SPI–WG blend with a weight ratio of 7:3 was used as a protein matrix to test the effects of saccharides (Grabowskaet al.2014; Krintiraset al.2014, 2015; Dekkerset al.2018).Textural properties of extrudates before and after thermal treatments (pasteurization and commercial sterilization) were measured to determine their thermal stability.The microscopic structure of extrudates was observed with a confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM).The rheological properties of material blends with water were determined with a closed-cavity rheometer.The status or distribution of water in extrudates was analyzed with low-field nuclear magnetic resonance (LF-NMR).The water activity, color difference, and pH of the extrudates were also measured.

2.Materials and methods

2.1.Materials

Soy protein isolates (SPI) and wheat glutens (WG) were purchased from Shandong Shansong Soy Protein Co., Ltd., and Binzhou Zhongyu Food Co., Ltd., respectively.The SPI contains 92.3 wt% protein, 0.5 wt% saccharides, 0.3 wt% ash, 0.5 wt% fat, and 6.4 wt% moisture.The WG contains 85.6 wt% protein, 5.0 wt% saccharides, 0.9 wt% ash, 0.8 wt% fat, and 7.7 wt% moisture.Maltodextrins of dextrose equivalent 10 (MD10) and 20 (MD20) were purchased from Yihai Kerry Arawana Holdings Co., Ltd.Wheat starch (WS) was purchased from Henan Feitian Agricultural Development Co., Ltd., with amylose content of 26.65 wt% (dry basis) and moisture content of 9.28 wt%.Round beef (steak) was purchased from a local supermarket within 72 h of slaughter.

2.2.Methods

Molecular weight distribution of saccharidesThe molecular weight distribution of maltodextrin and starch was evaluated using an HPLC system (Waters 1525 EF, Waters Corporation, MA, USA) equipped with a differential refractive index detector (Waters 2414, Waters Corporation, MA, USA) and a gel filtration column (Ultrahydrogel? Linear 300 mm×7.8 mm, Waters Corporation, MA, USA) (Liuet al.2023).

First, 10 mL of ultrapure water was mixed with MD10, MD20, or WS (100 mg).The WS suspension was heated in boiling water for 2 h, followed by centrifugation.The WS supernatant, MD10 or MD20 solution, was then passed through a 0.45-μm membrane filter before further analysis.The flow rate of the mobile phase (0.1 mol L–1NaNO3) was 0.5 mL min–1, and the temperature of the column was 40°C.

Dextran standards of 2 000 000, 300 600, 135 350, 21 400, 9 750, and 2 700 Da, as well as glucose (180 Da), were used to establish a calibration curve.The molecular weights of WS, MD10, and MD20 were calculated using the Empower Software version 3 (Waters Corporation, MA, USA), as shown in the following equation:

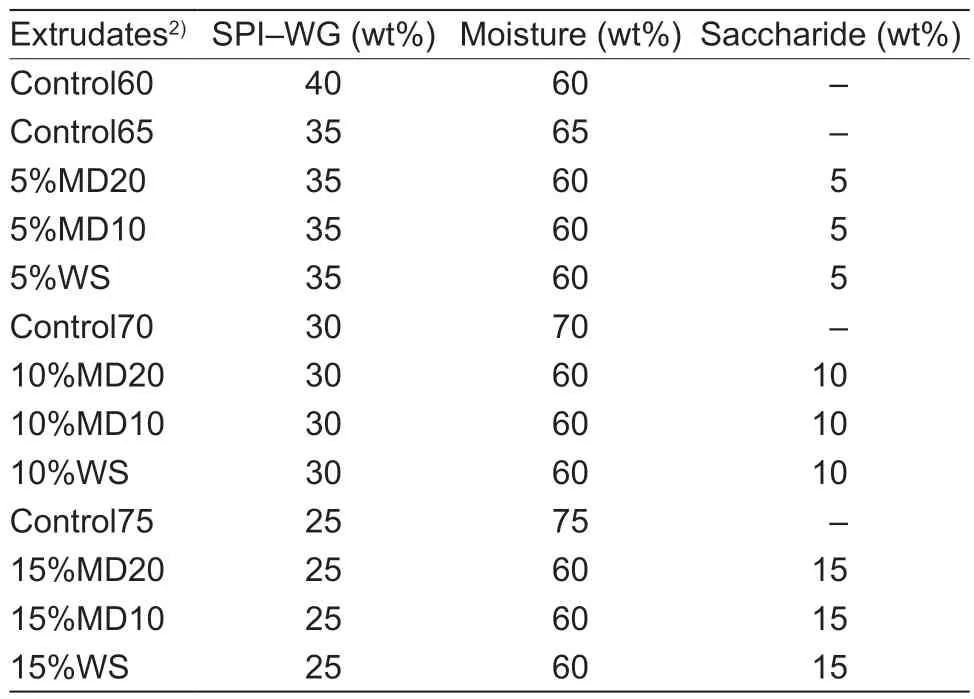

Extrusion processSPI and WG powder were mixed in a weight ratio of 7:3 and extruded with moisture contents of 60 wt%, 65 wt%, 70 wt%, and 75 wt% as control samples, namely, Control60, Control65, Control70, and Control75, respectively.Different amounts of MD20, MD10, or WS were added to prepare extrudates.The formulations are specified in Table 1.

Table 1 Formulation of extrudates1)

Extrusion experiments were conducted using a twinscrew extruder (ZE-16, ATS Nano Technology (Suzhou) Co., Ltd., China).The protein and saccharide mixtures were fed into the extruder at a speed of 0.4 kg h–1(dry basis).Based on preliminary experiments, the screw speed was set to 200 r min–1, and the extruderbarrel temperatures were kept at 30, 40, 60, 140, 150, and 150°C sequentially from the starting zone to the ending zone.A 2 394 mm×37 mm×5 mm cooling die was connected to the end of the extruder barrel and maintained at 70°C with running water.

Thermal treatment for extrudates and beefExtrudates were collected and packaged in retort pouches using a vacuum packing machine.Part of the extrudates was pasteurized at 70°C for 30 min or sterilized at 121°C for 20 min.Pasteurization was carried out in a water bath, and sterilization was carried out using an autoclave.

Round beef (steak) purchased from a local supermarket was cut into hunks of approximately 15 cm ×10 cm×5 cm, vacuum packaged, and cooked for an hour at 72, 85, 100, or 121°C.

Textural propertiesA texture analyzer (TA-XT plus, Stable Micro Systems Ltd., UK) was used to analyze the textural properties of extrudates.Before testing, the beef (steak) and extrudates were taken out of the refrigerator and allowed to equilibrate to room temperature (25°C).Each 10 mm×10 mm square sample was cut with an A/CKB probe (craft knife blade) perpendicular and parallel to the extrusion flow or muscle fiber.The probe achieved a 95% strain of the initial sample thickness while maintaining a constant test speed of 1 mm s–1.The detected peak force was recorded as hardness in either the perpendicular or parallel direction.The ratio of hardness in the perpendicular and parallel directions is defined as the texturization degree.Five replicate measurements were carried out for each sample.

Microscopic structureBefore staining, samples were cut with a frozen section into slices (20 μm thick) perpendicular and parallel to the extrusion flow.Rhodamine B (0.1 wt%, 1 mg mL–1) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC, w/w 0.1%, 1 mg mL–1) were mixed and dissolved in 75 wt% ethanol.The slices were stained for 10 min before washing them with 75 wt% ethanol.A high-resolution confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM880, Carl Zeiss AG, Germany) with a ×10 objective lens was used to excite FITC and Rhodamine B at excitation wavelengths of 488 and 552 nm, respectively.

Rheological propertiesBlends were prepared by combining, on a dry basis, SPI–WG and various saccharide powders with deionized water and storing them overnight in hermetically sealed plastic bags at 4°C to allow complete hydration.Approximately 5 g of the sample was held between two pieces of plastic foil in the closed-cavity rheometer (RPA elite, TA instruments, USA) and sealed with a closing pressure of 4.5 bar to prevent water evaporation at high temperatures.A temperature sweep (45–140°C) was performed at 15% amplitude and 10 Hz frequency with a linear temperature ramp rate of 10 K min–1.After the temperature sweep test, the material was subjected to an isothermal process at 140°C for 3 min before being cooled to 70°C in about 10 min by blowing dry cold air onto the disk.

Water activityWater activity (aw) values of the extrudates were measured using a dew point water activity meter (AquaLab 4TEV, METER Group, Inc., USA).

Status and distribution of waterExtrudates were cut into 20 mm×5 mm×5 mm blocks and placed in a test tube.Before testing, all samples were allowed to equilibrate to room temperature.The proton relaxation signal of each sample was recorded.The water distribution of the extrudates was measured with an NMR analyzer (MesoMR23-060V-I, Suzhou Niumag Analytical Instrument Corporation, China).A free induction decay (FID) experiment was used to calibrate the system.A Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) pulse sequence was used as the test mode for spin–spin relaxation time (T2) measurements.The following are the experimental parameters: number sampling (NS) was 8, time wait (TW) was 3 000, number of echoes (NECH) was 8 000, and echo time (TE) was 0.3.

ColorThe color was characterized by L*, a* and b* values: L* for lightness, a* for redness, and b* for yellowness.These values were obtained using an automatic colorimeter (WB2000-IXA, Beijing Kangguang Optical Instrument Co., Ltd., China).

pHApproximately 3 g of the extrudate was cut into small pieces and ground in a household grinder with 30 mL of 0.1 mol L–1KCl solution (Joyoung Co., Ltd., Shandong, China).The pH value of the solutions was measured using a pH meter (Mettler-Toledo International Inc., Columbus, OH, USA).

Statistical analysisExperiments were carried out in triplicate unless otherwise stated above.All data analyses were conducted using the analysis of variance with the Statistical Product and Service Solutions Software (version 17.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA).The Waller–Duncan test was used to evaluate extrudate comparisons.A probability level <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.Data are presented as means±standard deviation.

3.Results and discussion

3.1.Textural properties

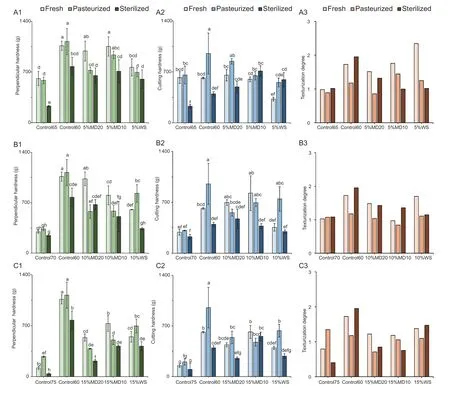

Textural properties of high-moisture extrudates, especially their hardness and texturization degree, are important indicators of their resemblance to real meat (Chenet al.2010; Fanget al.2014; Zhanget al.2019).Fig.1 depicts the hardness and texturization degree of fresh, pasteurized, and sterilized extrudates, indicating the effect of maltodextrin molecular weight on the thermal stability of SPI–WG-based extrudates.The addition of 5%MD20 and 5%MD10 significantly increased the perpendicular hardness of fresh extrudates by 62 and 73%, respectively; however, it had little effect on parallel hardness (Fig.1-A).This effect is comparable to the Control60.However, the addition of 5%WS did not improve the fresh product hardness significantly; at the same time, it significantly weakened the parallel hardness.In terms of the stability of extrudates against pasteurization, 5%MD10 addition resulted in the highest thermal stability (in terms of hardness) in both directions and texturization degree.Meanwhile, 5%MD20, 5%WS addition, or Control60 fail to maintain high thermal stability of texture, as they increased the parallel hardness of extrudates after pasteurization, resulting in a significant decrease in texturization degree.During sterilization, none of the additives could effectively prevent the weakening effect of heating on the perpendicular hardness or texturization degree.However, a 5% addition of MD10 and WS could increase the parallel hardness of extrudates after sterilization.

Fig.1-B and C depict the effect of 10 and 15% saccharide addition on the texture and thermal stability.Control70 and Control75 had low hardness in both directions (Fig.1-B1 and B2, Fig.1-C1 and C2), as well as low texturization degree (Fig.1-B3 and C3).This indicated that extrudates containing 30 and 25% SPI–WG had poor structure and almost no anisotropy.When 10% maltodextrin and starch were added, extrudates’ hardness and texturization degree significantly improved, almost equal to that of Control60.The addition of 10% MD20 and MD10 to the Control70 system had no effect on the stability of extrudates against sterilization processing.For the 15% saccharide addition, all three saccharides could only marginally enhance the hardness of extrudates and did not improve the thermal stability of hardness.

Fig.1 Textural properties of extrudates before and after heating processing.A, Control65, Control60, and extrudates with 5% saccharide addition.B, Control70, Control60, and extrudates with 10% saccharide addition.C, Control75, Control60, and extrudates with 15% saccharide addition before and after heating processing.1, perpendicular hardness; 2, parallel hardness; and 3, texturization degree.Data are mean±SD (n=5).Different letters in the same figure indicate statistically significant differences (P<0.05).

The hardness and texturization degree of round beef (steak) and extrudates were measured for comparison (Appendix A).When the heating temperature increased to 100°C, round beef hardness in the parallel and perpendicular directions to the muscle fibers decreased continuously.However, the texturization degree changed only marginally between 1.2 and 1.5.

The difference in texture and thermal stability of extrudates with MD20, MD10, or WS addition was most likely caused by protein–oligosaccharide/starch interaction.The weight-average molecular weight of WS was larger than 413 kDa.The molecular weight distribution of MD10 ranged from 2 to 122 kDa, while that of MD20 was from 1 to 48 kDa (details can be seen in Appendix B).Small-molecule saccharides can be effective plasticizers, while the plasticization ability of medium molecular weight saccharides can be limited (Ghanbarzadehet al.2006; Aleeet al.2021).Plasticization attracts water molecules and destroys intermolecular or intramolecular hydrogen bonds, possibly reducing the intermolecular interactions between the molecular chains and increasing the plasticity of extrudates (Gaoet al.2019).Phase separation was reported in high molecular weight maltodextrin (approximate dextrose equivalent (DE)=3)-caseinate gelation systems (Manojet al.1996), high molecular weight maltodextrin (DE=2 & 6)–gelatin gelation systems (Kasapiset al.1993a, b, c, d), and starch–gelatin gel systems (Firoozmandet al.2009; Firoozmand and Rousseau 2013).Semenova (1996) used light scattering to study the pair interaction between dextran (48, 270, and 2 500 kDa) and soy globulin and reported that an increase in dextran molecular weight favored their complex coacervation with soy globulin.Saccharides with low molecular weight in MD20 and MD10 mainly acted as plasticizers, while those with high molecular weight in MD10 and WS mainly promoted phase separation.Furthermore, polysaccharides can also be used as a crosslinker to alter protein conformation and bind to protein side groupsviathe Maillard reaction, increasing macromolecule texturization and producing network structures with high stability (Xinet al.2009; Caillardet al.2010).On the other hand, starch may have a different effect from maltodextrins.For the systems of protein and WS, those with higher moisture showed higher thermal stability against pasteurization or sterilization, suggesting that continuous gelatinization of starch may benefit the tolerance of extrudates against subsequent heat processing.According to Aroraet al.(2020), gelatinization is promoted by physical stresses experienced by starch during extrusion.A higher amount of starch in the feed requires higher shear stress or longer residence time to achieve a similar degree of gelatinization.The addition of MD20 with relatively small molecules had a limited effect on the thermal stability of extrudates due to plasticization.The addition of MD10 or WS with relatively small molecules promoted phase separation and had greater improvement on pasteurization than sterilization.Thus, the effects of maltodextrin or starch on texturization degree or thermal stability are likely to be heavily influenced by the molecular weight distribution and the dominant interaction between saccharide and protein-plasticizing effect or phase separation effects or non-disulfide covalent bond.Furthermore, the high temperature of sterilization could exceed the Tmof extrudates, resulting in a lower tolerance against sterilization than pasteurization.

3.2.Microscopic structure

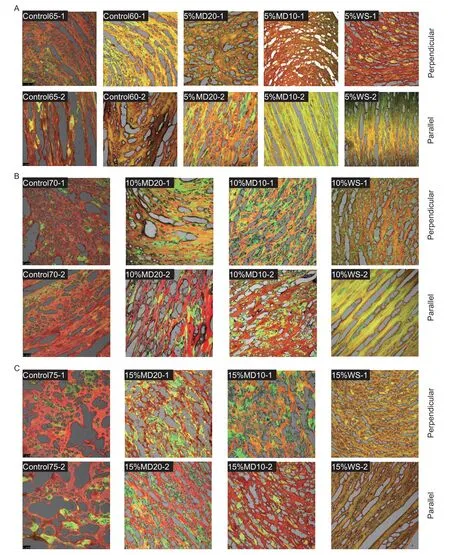

Rhodamine B stains SPI and WG red and has a higher affinity for protein than for starch (van de Veldeet al.2002; Dekkerset al.2018), whereas FITC can turn both saccharide and protein green (Wanget al.2019).Orange and yellow, which are thought to be proteins, are displayed in the region that has been stained both green and red.Only FITC, which is thought to be saccharide, can turn the area with a low affinity for Rhodamine B green (Grabowskaet al.2016; Dekkerset al.2018; Wanget al.2019).

Fig.2 shows CLSM images of extrudates in perpendicular and parallel directions.For controls, the density and regularity of extrudates in both directions were reduced when the moisture content increased from 60 to 75%.When maltodextrin or starch was added, all extrudates had a higher structural density.The density of extrudates also correlated with the hardness.The hardness of the extrudates increased with the structural density (Fig.1).In terms of extrudate regularity, the best effect of MD10 was seen in the samples with 5% saccharide addition.While in a 70% moisture system, the effect of starch was the greatest, while MD10 and MD20 were similar.In a 75% moisture system, the effect of starch was still the best, while MD20 did not perform well.The formulation with 5%MD10, 10%WS, and 15%WS not only increased the density of extrudates but also improved the regularity in both directions.In contrast, the distribution of MD20, MD10, and WS in the extrudates varied as well.In the 65% moisture system, the distribution of 5%WS in the extrudates was scattered as clusters, unlike the uniform distribution observed in MD20 and MD10.In the case of 70 and 75% moisture systems, the distribution of WS was more uniform than that in MD20 and MD10.

All these results suggest that the interaction between proteins and maltodextrin/starch during extrusion and cooling stages might differ.In most cases, the small and large molecular weight components in the formulation perform different functions.Small molecules (MD20, MD10) act as plasticizers (Ghanbarzadehet al.2006; Aleeet al.2021), and large molecules (MD10, WS) facilitate phase separation (Manojet al.1996).Thus, the roles that maltodextrin (especially MD10) plays in extrusion depend on the composition and content of their large and small molecular fractions.Starch, when added to the low-moisture system (60% moisture) that is insufficient for complete gelatinization during extrusion, appears to increase the density of extrudates but cannot improve regularity effectively (Fig.2-A).Starch was able to improve both density and regularity of fibers when added into high-moisture systems (70 or 75% moisture) (Fig.2-B and C).

Fig.2 Confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) images of extrudates along perpendicular and parallel directions.A, Control65, Control60, 5%MD20, 5%MD10, and 5%WS.B, Control70, 10%MD20, 10%MD10, and 10%WS.C, Control75, 15%MD20, 15%MD10, and 15%WS.

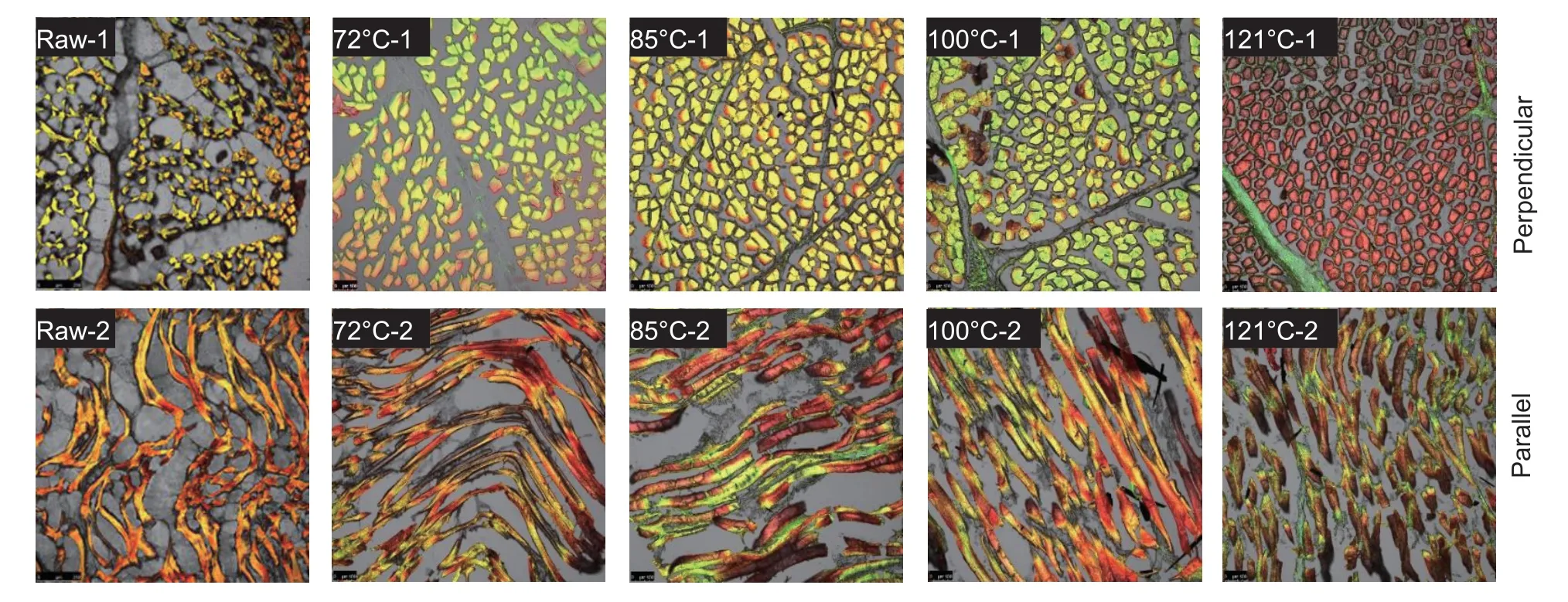

CLSM images of raw and cooked beef along two directions are shown in Fig.3.In the perpendicular direction, bundles of clearly separated muscle fibers expanded as the heating temperature increased from 72 to 100°C, then shrank when the temperature increased to 121°C.Similar to the results on the texture of beef (Appendix A), long and curved fibers gradually became shorter and straighter in the parallel direction.

Fig.3 Confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) images of raw beef and the beef cooked for 1 h at 72, 85, 100, and 121°C along perpendicular and parellel directions.

Notably, the structure of high-moisture extrudates and beef is notably different.Despite the macroscopic fibrous structure (Appendix C) of high-moisture extrudates, their lack of fiber structure on a microscale, especially the lack of tube and bundle structure in the parallel direction, could be the structural reason for the poor similitude of current extrudates to real meat.

3.3.Rheological properties

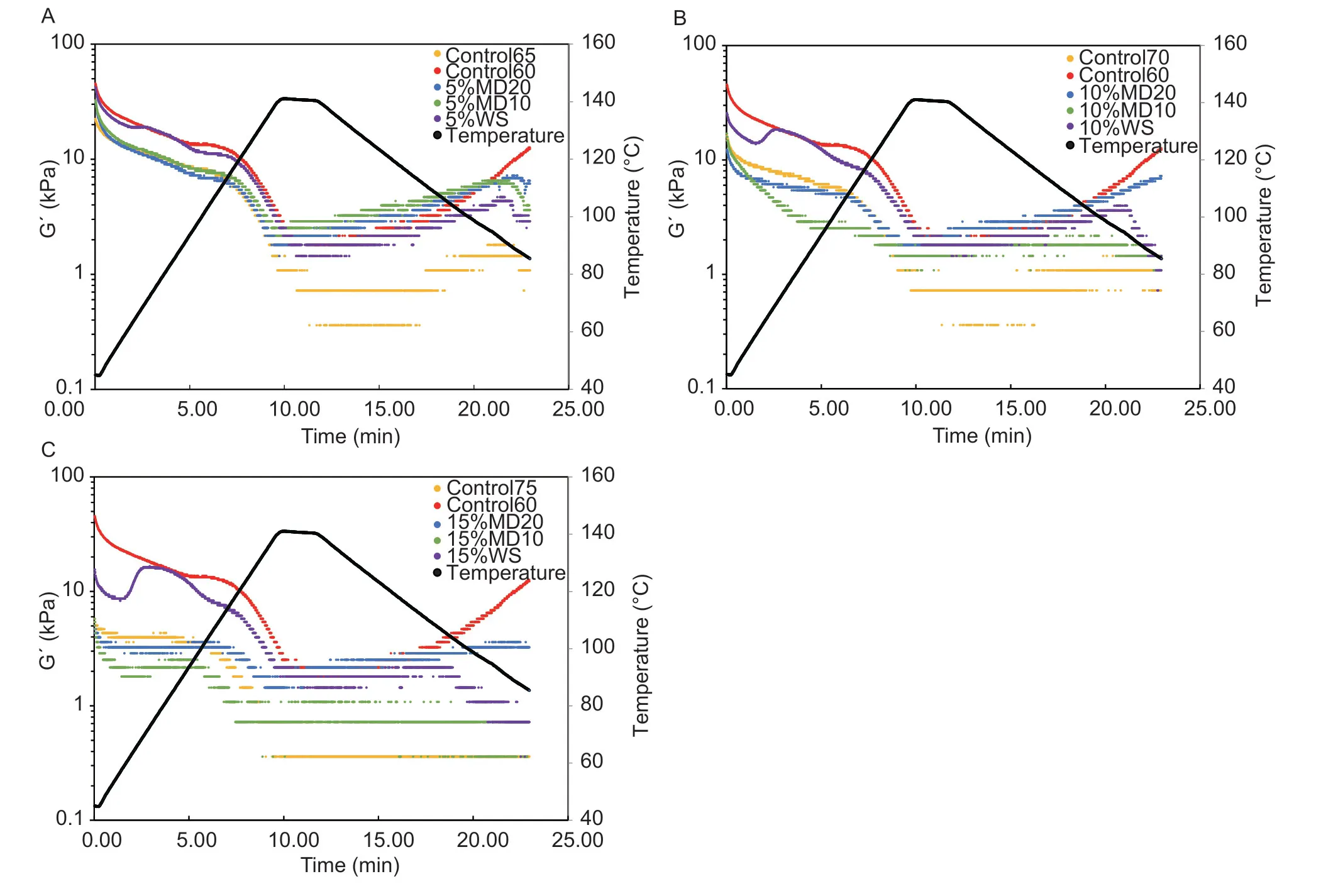

A close cavity rheometer was used to measure the elastic modulus (G′) of the samples during heating, isothermal, and cooling processes in order to examine the thermal behavior and interaction of protein and saccharides during extrusion.

The G′ of 65% moisture SPI–WG system began to significantly decrease at 110°C, and it was unable to recover during the subsequent heating, isothermal, and cooling process (Fig.4-A).The temperature at which G′ dropped sharply may be the melting temperature (Tm) of the blends (Levine and Slade 1988; Goffet al.1993; Roos 1995).In the samples with 5% MD20, MD10, or WS addition, G′ dropped drastically at 112, 114, or 115°C, respectively.Their higher Tmcorresponded to their higher thermal stability compared to Control65.Moreover, in the cooling process, their G′ were restored to a different extent and then dropped again at around 85–90°C.For Control60, the viscoelasticity was restored in the cooling process continuously without falling again.The results presented in Fig.4-B and C had a similar trend.The elastic modulus of Control70 started to drop drastically at 105°C and could hardly recover afterward.At 104°C, which is almost the same as Control70, the elastic modulus of 10% MD20 and MD10 began to decrease significantly.This indicates that 10% MD20 and MD10 had no positive effect on thermal stability.Although the curve of Control75 was not continuous, it can be seen that its Tmwas lower than that of Control70.

The plasticization effect is associated with the protein–saccharide interactions (Kasapiset al.1993a, b, c, d; Manojet al.1996) or the variation in the temperature at which the elastic modulus decreases significantly (Ghanbarzadehet al.2006; Gaoet al.2019; Aleeet al.2021).For low-moisture systems, such as 65%, both maltodextrins with different DE values increased Tm, indicating that their possible interactions with protein may have contributed to phase separation (Suchkovet al.1988; Yuryevet al.1991; Tolstoguzov 1993; Grinberg and Tolstoguzov 1997).For high-moisture systems, such as 70 and 75%, both maltodextrins with different DE values did not increase Tm, indicating that the plasticization effects of small molecular maltodextrin (especially in MD20) and the protein–saccharide interaction of large molecular saccharide (especially in MD10) might have the opposite effect.Small molecular plasticizers lower Tm(Roos and Karel 1991; Sladeet al.1991; Goffet al.1993; McCurdyet al.1994), while large molecular saccharides promote phase separation and improve stability (Kasapiset al.1993a, b, c, d; Manojet al.1996).Additionally, the elastic modulus of 5% WS showed a slight increase at 63°C during heating, indicating a link with starch gelatinization (Sarifudin and Assiry 2014; Kauret al.2015; Aroraet al.2020).This phenomenon of gelatinization was more evident in 10%WS (Fig.4-B) and 15%WS (Fig.4-C).Furthermore, the addition of 5%WS to low moisture (65%) system had a negative impact on the G′ of the blends, especially during the G′ restoring and the ending stages, whereas the addition of 10 and 15% to high moisture systems (70 and 75% in Control70 and Control75, respectively) had a positive impact on the G′ of the blends.These results are consistent with the textural results (Fig.1) and CLSM images (Fig.2).This indicates that if starch is in a water-rich environment that favors its gelatinization during extrusion, it could promote phase separation andraise the texturization degree of the extrudates.

Fig.4 Elastic modulus (G′) measured during temperature sweep experiment at 15% strain and 10 Hz frequency.A, Control65, Control60, and extrudates with 5% saccharide addition.B, Control70, Control60, and extrudates with 10% saccharide addition.C, Control75, Control60, and extrudates with 15% saccharide addition.

Comparing the results of Tmand CLSM (Fig.2), it can be further opined that saccharides with small molecular weight lowered Tmdue to the plasticization effect (Ghanbarzadehet al.2006; Gaoet al.2019; Aleeet al.2021), promoted material flow at the cooling stage, and, therefore, improved the regularity of extrudates.Meanwhile, large molecular weight saccharide was conducive to phase separation and also improved the regularity of extrudates (Suchkovet al.1988; Yuryevet al.1991; Tolstoguzov 1993; Grinberg and Tolstoguzov 1997).In terms of the relationship between Tmand stability, it could be seen that blends with higher Tmgave rise to extrudates with higher stability against pasteurization.Although small molecular weight saccharides improved the texturization degree due to their plasticizing effect, they decreased thermal stability.Because large molecular saccharides encourage phase separation, they enhance texturization degree and thermal stability.Pasteurization at 70°C (under Tm) did not reduce the G′ significantly as sterilization did.This also suggested that the extrudate had higher stability against pasteurization than sterilization.Starch can promote phase separation and increase the density and regularity of extrudates if it is thoroughly gelatinized during extrusion.If starch is not fully gelatinized during the extrusion process, it will be further gelatinized during the subsequent sterilization process, which will help improve the stability of the extrudate.

3.4.Water activity, status, and distribution

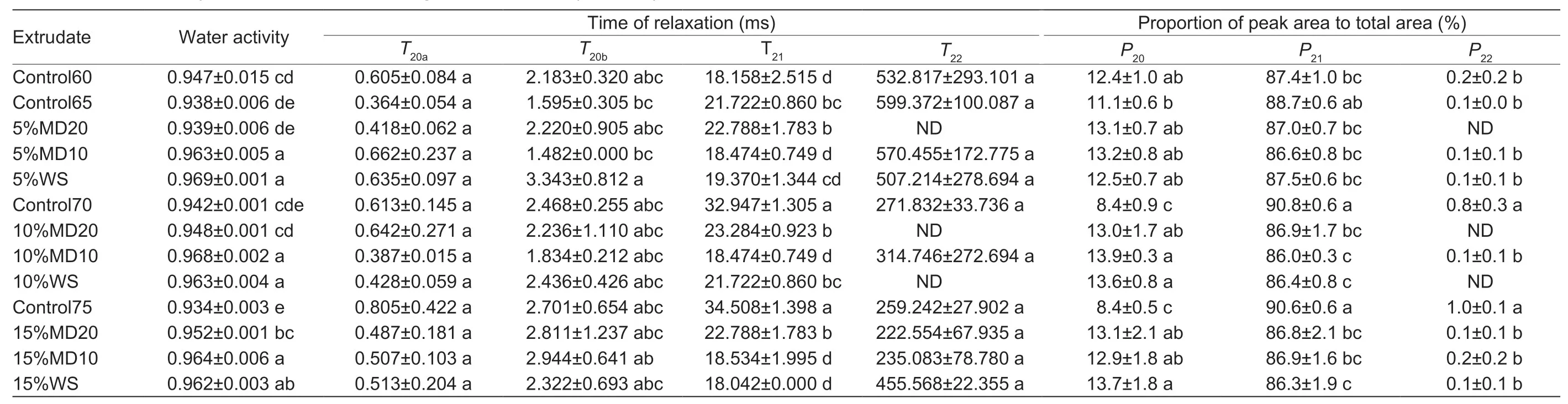

The mobility and availability of water in food systems are reflected in water activity.Thus, water activity might be linked to Tgand Tm, both of which have an impact on food stability (McCurdyet al.1994).The water status in the food systems can be determined using LF-NMR.Relaxation time T2(1H proton nucleus) along thex–yaxes (transverse or spin–spin relaxation) is used to characterize the distribution and mobility of various kinds of water molecules in samples (Vittadini and Vodovotz 2007).A shorter relaxation time indicates a firmer interaction between water and other components (Zhaoet al.2021).In this study, four relaxation times (T20a, T20b, T21, and T22) were observed, which corresponded to the four peaks of T2curves.They could be classified into three different categories of water (Bertramet al.2001; Wanget al.2020): bound water (T20, 0–10 ms, including T20a, 0–1 ms, and T20b, 1–10 ms) (Liuet al.2015), bonding to proteins with hydrogen bonds, immobilized water (T21, 10–100 ms) (Li Tet al.2014), and free water (T22, above 100 ms, not detected in some extrudates) (Li Yet al.2014).

In thelow moisture(65%) system, the addition of 5% MD20, MD10, and WS did not change the moisture distribution or relaxation time (Table 2).While in high moisture (70 and 75%) systems, the addition of 10 or 15% MD20, MD10, and WS decreased the immobilized water content and increased the bound water compared with that of the control, although there was no obvious difference in the moisture distribution or the relaxation time of the samples of MD20, MD10, and WS.The addition of polysaccharides slightly increased the water activity when compared with that of the control.Based on the proportion of bound water and immobilized water, as well as water activity of saccharide-added extrudates in low (65%) and high-moisture systems (70 and 75%), it could be suggested that large molecular dextrin or starch, which promoted phase separation, could increase the proportion of bound water.As a result, the probability of protein forming gels with water was reduced, which promoted the separation of water-rich and -deficient phases and improved the texturization degree.

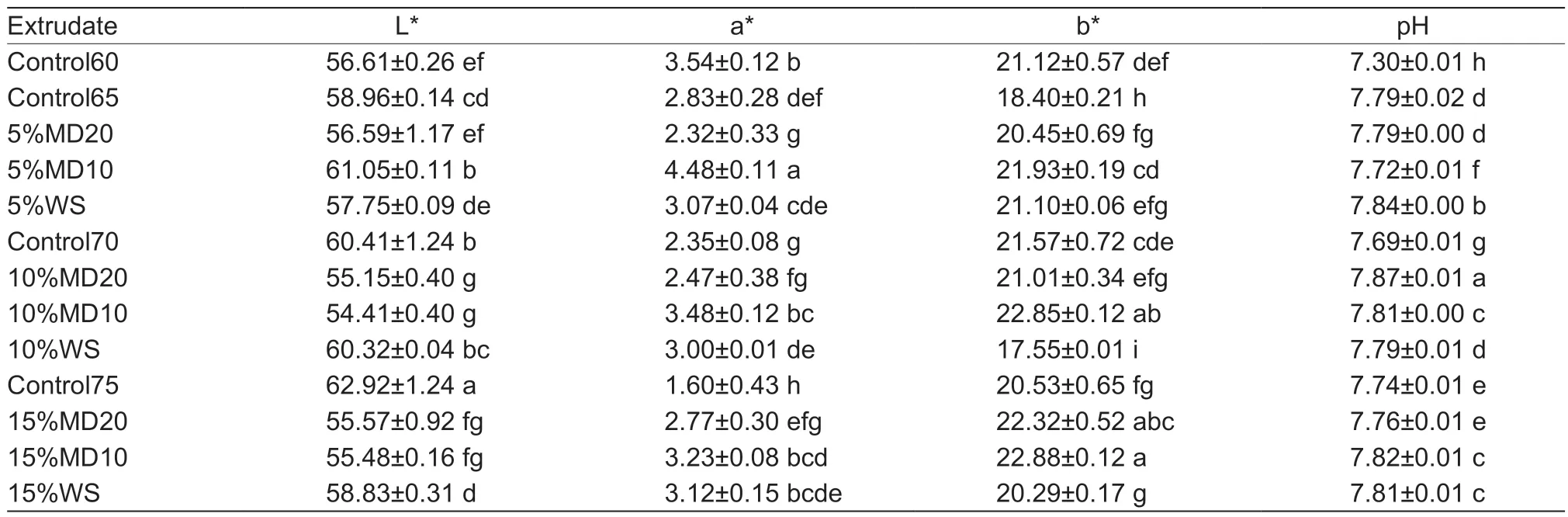

3.5.Color difference and pH

It is commonly accepted that the Maillard reaction promotes covalent conjugation between proteins and saccharides, particularly in reducing sugar residues.The product’s distinct color and a change in pH can indicate the degree of Maillard reaction (Ellis 1959).The brightness of the control samples increased with the moisture content (Table 3).This may be related to the lower level of water–protein binding and correspond to the lower proportion of bound water and a higher proportion of immobilized water (Table 2).However, the addition of saccharide had little effect on the brightness of the samples compared to Control60, except for 10%MD10 and 10%MD20.Furthermore, adding MD20, MD10, and WS to any of the three moisture systems did not lower pH, indicating that the Maillard reaction in the maltodextrin and SPI–WG mixture was limited.Differences in texture might have caused slight alterations in L*, a*, and b* values.

Table 2 Water activity and low-field nuclear magnetic resonance (LF-NMR) parameters of extrudates

Table 3 Color differences and pH values of extrudates1)

4.Conclusion

This study found that the molecular weight distribution of saccharides, plasticization or phase separation effect, and the covalent interaction between saccharide and protein (e.g., the Maillard reaction) are the factors underpinning the effect of maltodextrin or starch on the texturization degree and heat stability during pasteurization or sterilization of high-moisture textured protein.Small molecular weight maltodextrin acted as a plasticizer, reduced Tm, increased extrudate mobility during cooling, and facilitated the separation of water-rich and -deficient phases, thereby improving the texturization degree.Small molecular weight maltodextrin did not improve the thermal stability of extrudatesdue to the plasticization effect.Large molecular weight maltodextrin facilitated phase separation in extrudates, increased the Tm, increased texturization degree, and improved their thermal stability.Thoroughly gelatinized starch during extrusion could also promote phase separation and increase the density and regularity of extrudates.The thermal stability of the extrudate could also be improved during subsequent pasteurization or sterilization when starch was only partially gelatinized during the extrusion stage.Additional research is required to precisely determine the dose-effect relationship of saccharide addition and the effect of dextrin’s molecular weight or starch structure (e.g., amylose–amylopectin ratio).

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32202081) and the National Key Research and Development Plan of China (2021YFC2101402).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendicesassociated with this paper are available on https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jia.2023.04.013

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年5期

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年5期

- Journal of Integrative Agriculture的其它文章

- Herbicidal activity and biochemical characteristics of the botanical drupacine against Amaranthus retroflexus L.

- Developing a duplex ARMS-qPCR method to differentiate genotype l and ll African swine fever viruses based on their B646L genes

- Elucidation of the structure, antioxidant, and interfacial properties of flaxseed proteins tailored by microwave treatment

- Effects of planting patterns plastic film mulching on soil temperature, moisture, functional bacteria and yield of winter wheat in the Loess Plateau of China

- lnversion tillage with straw incorporation affects the patterns of soil microbial co-occurrence and multi-nutrient cycling in a Hapli-Udic Cambisol

- The effects of co-utilizing green manure and rice straw on soil aggregates and soil carbon stability in a paddy soil in southern China