Revealing the process of storage protein rebalancing in high quality protein maize by proteomic and transcriptomic

ZHAO Hai-liang, QIN Yao, XIAO Zi-yi, SUN Qin, GONG Dian-ming, QIU Fa-zhan

National Key Laboratory of Crop Genetic Improvement/Hubei Hongshan Laboratory/College of Plant Science and Technology, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan 430070, P.R.China

Abstract Quality protein maize (QPM) (Zea mays L.) varieties contain enhanced levels of tryptophan and lysine, exhibiting improved nutritive value for humans and livestock.However, breeding QPM varieties remains challenging due to the complex process of rebalancing storage protein.This study conducted transcriptome and proteome analyses to investigate the process of storage proteins rebalancing in opaque2 (o2) and QPM.We found a weak correlation between the transcriptome and proteome, suggesting a significant modulating effect of post-transcriptional events on non-zein protein abundances in Mo17o2 and QPM.These results highlight the advantages of proteomics.Compared with Mo17, 672 differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) were identified both in Mo17o2 and QPM, and several of them were associated with storage protein, starch, and amino acid synthesis.We identified 178 non-zeins as DEPs in Mo17o2 and QPM kernels.The up-regulated non-zein DEPs were enriched in lysine, tryptophan, and methionine, which affected the protein quality.Co-expression network analysis identified regulators of storage protein synthesis in QPM, including O2, PBF1, and several transcription factors.Our results revealed how storage protein rebalancing occurs and identified nonzein DEPs that may facilitate superior-quality QPM breeding.

Keywords: quality protein maize, opaque2, qγ27, protein body, storage protein, iTRAQ

1.Introduction

Maize kernel is a major part of human and livestock diets and one of the planet’s most important food sources.Storage proteins account for ~10% of the maize kernel weight.They are composed of zeins and non-zeins, 80% of which are stored in the protein body (PB).Therefore, the process of PB organization is critical for the accumulation of storage proteins and is highly dependent on the synthesis of zeins and non-zeins.Moreover, 62–74% of the storage proteins are zeins (Flint-Garciaet al.2009).Unfortunately, zein proteins, especially α-zein, have little or none of the essential amino acids lysine, tryptophan, and methionine (Wanget al.2003).The α-zein subfamily is the most abundant fraction of zeins, encoded by four gene families, includingz1A,z1B,z1D(19 kD α-zein), andz1C(22 kD α-zein).The expression levels of these zein genes are extremely high in maize endosperm (Wooet al.2001).Therefore, maize storage proteins are deficient in the essential amino acids, lysine, tryptophan, and methionine.Due to the low nutritional quality of maize kernels, livestock producers must add soybean meal to their corn-based animal feed to provide high-quality protein.

The classic mutanto2, with a marked increase in lysine content in the endosperm (Mertzet al.1964), gave rise to a new concept in the production of maize kernels with high nutritional value.O2 is a b-ZIP transcription factor that regulates the transcription of the 19- and 22-kDa α-zein genes by transactivating the promoters ofz1A,z1B,z1C, andz1Dzein genes (Liet al.2015; Zhanet al.2018).The mutation ofo2led to a decrease in zein proteins and a concurrent increase in non-zein proteins rich in lysine and tryptophan; therefore, the protein value ofo2is higher than that of normal protein maize (Kies and Fox 1972; Guptaet al.1979).However, the chalky and soft texture ofo2kernels causes numerous problems, such as increased susceptibility to pests and diseases and difficulties in harvesting and storage, thus precluding its direct application.

Quality protein maize (QPM) was created based ono2modifiers, which alter the unfavorable traits ofo2and produce kernels with a hard, vitreous endosperm (Babuet al.2005; Gibbon and Larkins 2005).qγ27, a duplication in the 27-kDa γ-zein locus, was identified as a majoro2modifier that increases the expression of 27-kDa γ-zein to promote PB initiation and increase storage protein synthesis under theo2background (Yuanet al.2014; Liuet al.2016, 2019).Since the expression of 19- and 22-kDa α-zein genes was not affected byo2modifiers, QPM has less zein protein and increased amounts of non-zein protein.Therefore, QPM has a higher nutritional value than normal maize.Specifically, the QPM has approximately twice the tryptophan and lysine concentrations in protein compared to normal protein maize and can meet ~70% of human protein demand (Zarkadaset al.2000; Rosaleset al.2011).QPM increased lysine and non-zein protein contents by altering the balance of storage proteins, specifically by increasing the lysine-containing non-zein proteins and reducing 19- and 22-kDa α-zein synthesis in the endosperm (Huanget al.2004; Wuet al.2010; Mortonet al.2016).Further investigations are warranted to identify which non-zein proteins and their regulators play important roles in storage protein rebalancing.

This study applied transcriptome and isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification (iTRAQ)-based proteome analyses.It found that the processes of starch and sucrose metabolism, amino acid biosynthesis, and protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum were altered in the maizeo2mutant and QPM during the rapid production of storage protein in the developing kernel.Further analysis indicated that some DEPs identified ino2and QPM plants are non-zein proteins in PBs enriched in lysine and participate in PB organization to control storage protein balance.Furthermore, we identified several regulators and companions associated with storage protein rebalancing in QPM using the transcriptome data of 13 QPM and 32 normal protein maize inbred lines.Compared with previous studies, our results revealed the landscape of non-zein protein accumulation ino2and QPM kernels.Our findings provide new insight into the composition of non-zein proteins in PBs and the process of storage protein rebalancing in QPM.These findings could facilitate the breeding of QPM.

2.Materials and methods

2.1.Plant materials

To investigate non-zein protein accumulation ino2and QPM plants, we reciprocally crossed the maize inbred lines W64Ao2and Mo17 (which contains theqγ27locus).The F1was backcrossed with Mo17 by three generations to construct a near-isogenic line of Mo17o2.The study used the Mo17, Mo17o2, and QPM kernels segregated from the heterozygous mutant for transcriptome and proteome analyses.The maize plants used for the nearisogenic line construction were grown in the field in Wuhan, Hubei Province and Sanya, Hainan Province, China, and the plants used for sampling were grown in glass greenhouses in Wuhan.The temperature in the greenhouse was 25 to 32°C during maize pollination and early development stages.The primers used forqγ27ando2genotyping are listed in Appendix A.

2.2.RNA extraction and RNA-Seq

Total RNA was extracted from pooled Mo17, Mo17o2, or QPM endosperms obtained from the same segregating ears at 20 days after pollination (DAP) (30 kernels each sample) using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.After isopropanol precipitation, the RNA was resuspended in 50 μL of RNase-free water and treated with RNase-free DNaseI.Three independent biological replicates from three different ears were performed.cDNA libraries were constructed following the standard Illumina protocol and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq Platform by Novogene (Beijing, China).The sequence reads were trimmed using the tool Trimmomatic (v.0.33; http://www.usadellab.org/cms/?page5trimmomatic) and mapped to the B73 RefGen_v4.34 reference genome using the program HISAT2 (v.2.1.0; http://ccb.jhu.edu/software/hisat2/faq.shtml).The Program StringTie (v.1.3.3b) was employed to reconstruct the transcripts and to estimate gene expression levels (Perteaet al.2016).Significant differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified by DEseq2 (http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/devel/bioc/html/DESeq2.html) as those with an false discovery rates (FDR) value of the differential expression above the threshold (FDR<0.01, absolute value of log2(fold change)>0.5).The conjoint GO and KEGG term enrichment results were generated using the software “agriGOv2” (http://systemsbiology.cau.edu.cn/agriGOv2/#) and “g:Profiler” (http://biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/).RNA-seq data are available from the SRA database under the STUDY: PRJNA799496 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=PRJNA799496).

2.3.Measurement of storage proteins

A total of 30 mature endosperms were pooled as a single replicate.After soaking in water for 10–20 min, the kernel coats and embryos were removed from the kernels, ground into a fine powder in liquid nitrogen, and freeze-dried.Eight biological replicates were used for subsequent analysis.A 50-mg sample was incubated overnight in 1 mL of lysis buffer (12.5 mmol L–1of sodium borate, 0.2% (w/v) SDS, 10 mmol L–1DDT, 1% (w/v) cocktail (Merck), and 1% (w/v) phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) in a 37°C shaker.The mixture was centrifuged for 15 min at 13 000×g, after which 300 μL of supernatant was carefully transferred into two different 1.5 mL centrifuge tubes.One tube was used to estimate total protein; 700 μL of ethanol was added to the other tube, which was then incubated at 4°C on a shaker for 3 h and was centrifuged for 15 min at 13 000×g.The supernatant contained zeins, and the precipitate contained nonzeins.The total protein, zein, and non-zein proteins were quantified using the Modified BCA Protein Assay Kit (Sangon Biotech, Sonjiang, Shanghai, China), and the components of zein and non-zein proteins were analyzed by 4–15% SDS-PAGE.

2.4.Protein extraction and iTRAQ labeling

Given the maximum expression level ofO2andqγ27at 20 DAP (Chenet al.2014), and the rapid accumulation of non-zein proteins during this stage (Appendix B), we elected 20 DAP endosperm for proteomic analysis, with each replicate comprising 30 independent kernels.These endosperms were quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground into a fine powder with a mortar and pestle.Three biological replicates were used for subsequent analysis.Total proteins were extracted with 30 mL lysis buffer (12.5 mmol L–1of sodium borate, 0.2% (w/v) SDS, 10 mmol L–1DDT, 1% (w/v) cocktail (Merck), and 1% (w/v)phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) in a 4°C shaker for 3 h.The mixture was centrifuged for 15 min at 13 000×g, after which 10 mL of supernatant was carefully transferred into two 50-mL centrifuge tubes.A total of 23 mL of ethanol was added to the tube and then incubated at 25°C on a shaker for 3 h.The supernatant was aspirated gently, and the precipitate was centrifuged for 15 min at 13 000×g and washed twice with 70% alcohol.The protein sample was dissolved in DB protein lysis solution (8 mol L–1urea,100 mmol L–1Triethylamine borane (TEAB), pH=8.5), trypsin and 100 mmol L–1TEAB buffer were added to the tube to mix and digest at 37°C for 4 h, and trypsin and CaCl2were added and digested overnight.After adjusting the pH to less than 3 with formic acid, the mixture was centrifuged at 12 000×g at room temperature for 5 min.Then, the supernatant was slowly passed the C18 desalting column, the sample was washed three times with wash buffer (0.1% formic acid, 3% acetonitrile), and the eluent buffer (0.1% formic acid, 70% acetonitrile) was used to collect the protein.The digested peptide was dissolved in 100 μL of 100 mmol L–1TEAB buffer; then, the peptides were labeled with 41 μL of acetonitriledissolved TMT labeling reagents (iTRAQ?Reagent-8PLEX Multiplex Kit; Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, China).All labeled samples were multiplexed and desalted in peptide-desalting spin columns (89852; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Mobile phases A (2% acetonitrile, 98% water, and ammonia to pH=10) and B (98% acetonitrile, 2% water) were used to develop a gradient elution.The L-3000 HPLC System was used for fractional distillation at 45°C.The gradient was as follows: 5% B, 10 min; 5–20% B, 20 min; 20–40% B, 18 min; 40–50% B, 2 min; 50–70% B,3 min; 70–100% B, 1 min.The tryptic peptide was monitored under UV at a wavelength of 214 nm.

The shotgun proteomics analysis was performed on the EASY-nLC?1200 UHPLC System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) combined with the Orbitrap Q Exactive HF-X mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).Peptides were separated on a Reprosil-Pur 120 C18-AQ analytical column(15 cm×150 μm, 1.9 μm) using a 90-min linear gradient from 6 to 100% eluent B (0.1% FA in 80% acetonitrile (ACN)) in eluent A (0.1% FA in H2O) at a flow rate of 600 nL min–1.The solvent gradient was as follows: 6–15% B in 2 min; 15–40% B in 76.5 min; 40–50% B in 2 min; 50–55% B in 1 min; and 55–100% B in 8.5 min.

Orbitrap Exploris 480 mass spectrometer was operated with Nanospray Flex? (ESI) ion source with a spray voltage of 2.3 kV and a capillary temperature of 320°C.The full scan range of the mass spectrum was 350–1 500m/z, the resolution of the primary mass spectrometer was set to 60 000 (200m/z), the maximum capacity of the C-trap was 3×106, and the maximum injection time of the C-trap was 20 ms.The top 40 precursor ion were selected for higher-energy collisional dissociation fragment analysis at the resolution of 45 000 (200m/z), the maximum C-trap capacity of 5×104, the maximum C-trap injection time of 86 ms, the peptide fragmentation collision energy of 32%, the intensity threshold of 1.2×105, and the dynamic exclusion range of 20 s.The original mass spectrometry data were generated with these parameters (Fenget al.2022).

The Proteome Discoverer 2.2 (PD2.2, Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA) was used for database retrieval, peptide mapping, and protein quantitation with the database of “Zea_mays.AGPv4.pep” (Jiaoet al.2017).The search parameters were as follows: the mass tolerance of precursor ions of 10 ppm, the mass tolerance of fragment ions of 0.02 Da, the immobilized modification was the alkylation modification of cysteine, the variable modification was the methionine oxidation and the tandem mass tag (TMT) modification, the N-terminal was the acetylation modification and the TMT tag modification, allowing up to two missing cleavage sites.Peptide fragments and proteins with FDR of >1% were excluded.DEPs were identified with fold-changes >1.2 or <0.83 andP-value<0.05.

2.5.Weighted gene co-expression network analysis(WGCNA)

A gene co-expression network was constructed using the R package WGCNA (Langfelder and Horvath 2008; Zhanget al.2022).Thirteen QPM inbred lines and 32 normal protein maize inbred lines were selected in 368 diverse inbred lines according to theO2andqγ27locus (Fuet al.2013; Liet al.2013), with an adjacency matrix constructed based on normalized reads per kilobase per million mapped reads (RPKM) values (Appendix C).Modules were obtained using the automatic network construction function blockwiseModules with the parameters: softPower was 14, TOM-Type was adjacency, minModuleSize was 30, and mergeCutHeight was 0.2.Co-expression networks were visualized using the Cytoscape Software (Stuartet al.2003).

2.6.Statistical analysis

R Software (version 4.0.3) was used for statistical analysis and image processing.Continuous variables were expressed as the mean±standard deviation (SD) in the storage proteins measurement experiment, and eight biological replicates were used.Student’st-test was performed to test statistical differences between different treatments, andP-values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3.Results

3.1.Storage protein rebalancing in QPM

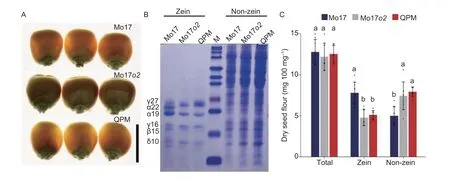

Maizeo2is a classical mutant with starchy endosperm showing decreased zein protein and increased nonzein protein accumulation.Theqγ27mutation contains a duplication of the 27-kDa γ-zein locus.It has been used to modifyo2mutant starchy endosperm to vitreous endosperm, resulting in a better amino acid balance (Liuet al.2016).In the Mo17o2, the mature kernels have an opaque, soft endosperm (Fig.1-A); by contrast, the mature kernel of QPM had no obvious difference in appearance from Mo17 and had a vitreous endosperm (Fig.1-A).The SDS-PAGE analysis showed that in Mo17o2, the levels of 19-kDa α-zein and 22-kDa α-zein decreased and disappeared, respectively, but the level of non-zein proteins increased, as compared with Mo17 (Fig.1-B and C).Moreover, the decreased accumulation of zein proteins and increased accumulation of non-zein proteins in QPM were the same as that of the Mo17o2, but the levels of 27-kDa γ-zein were increased in QPM compared with Mo17o2, consistent with the effect of the duplication inqγ27(Fig.1-B and C).Despite these changes in zein and non-zein protein accumulation, the dry kernel total protein content of Mo17o2and QPM did not change significantly compared with Mo17 (P=0.48 and 0.71, Fig.1-C).

Fig.1 Phenotypes of Mo17o2 and quality protein maize (QPM) (o2: qγ27) kernels.A, kernel phenotypes of Mo17, Mo17o2, and QPM mature kernels.Scale bars=1 cm.B, SDS-PAGE analysis of zein and non-zein proteins in the mature endosperm of Mo17, Mo17o2, and QPM kernels.C, the contents of proteins in Mo17, Mo17o2, and QPM mature kernels.Error bars represent the SD of eight independent replicates.Different lowercase letters mean significant difference between genotypes, as determined by Duncan’s multiple-comparison tests (P<0.05).*, P<0.05.

3.2.Transcriptomic differences between Mo17o2 and QPM endosperm

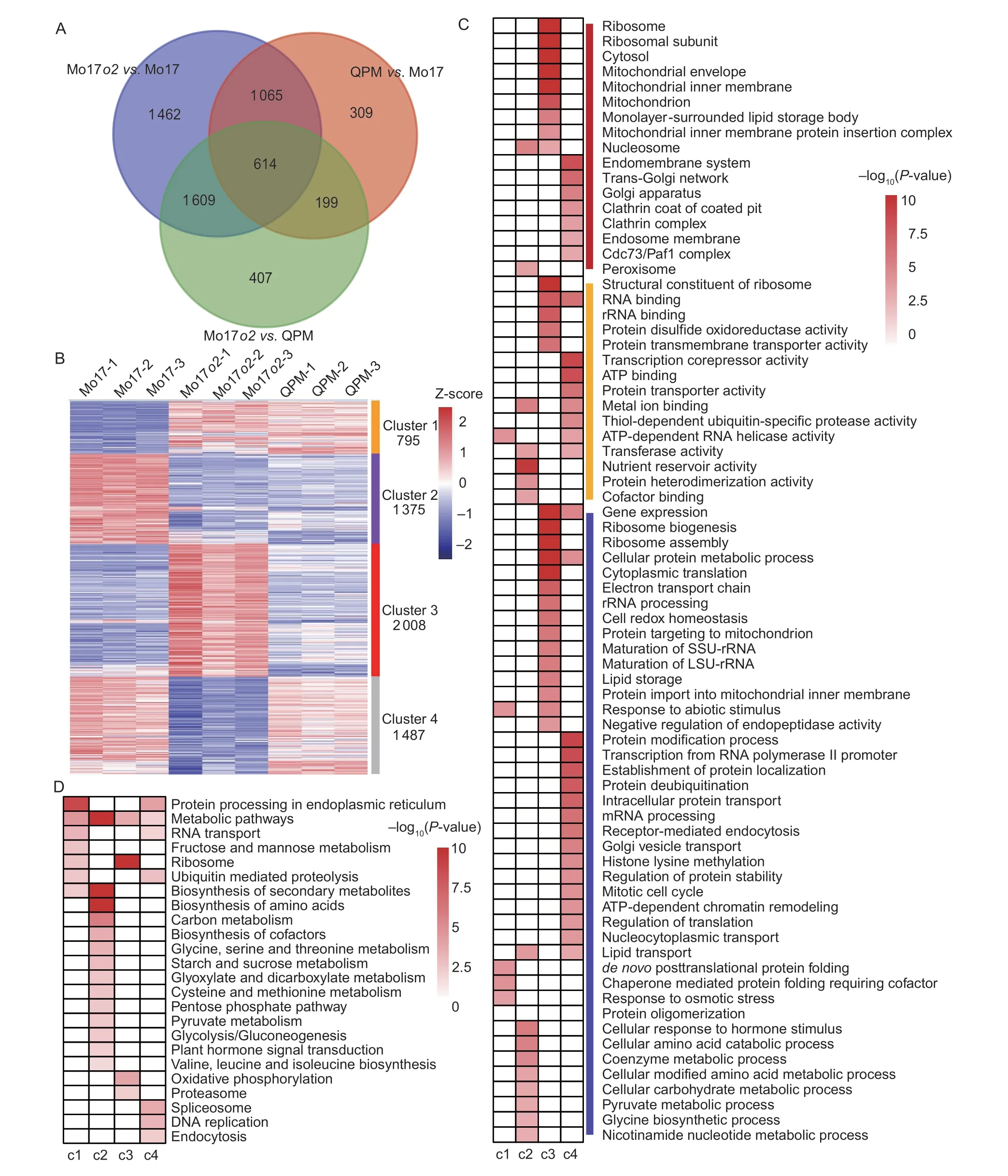

To understand the molecular basis of the phenotypic difference between theo2mutant and QPM, we harvested the endosperms of Mo17o2, QPM, and Mo17 kernels at 20 DAP.Approximately 20 million paired-end reads were obtained from each replicate and sample by RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), and ~88% aligned well with the maize genome sequence (Appendix D).A total of 2 187 DEGs were identified between QPM and Mo17 kernels.The number of DEGs between Mo17o2and Mo17 kernels was 4 750, over twice as many as those between QPM and Mo17 kernels, while 2 829 DEGs were identified between Mo17o2and QPM (Fig.2-A).

The DEGs could be divided into four clusters according to their expression levels.Cluster 1 contains 795 DEGs that were up-regulated in both Mo17o2and QPM.In Cluster 2, 1 375 DEGs were down-regulated in both Mo17o2and QPM.Cluster 3 includes 2 008 DEGs that were up-regulated only in Mo17o2.Cluster 4 contains 1 487 DEGs that were down-regulated only in Mo17o2(Fig.2-B; Appendix E).

Gene Ontology (GO) terms associated with response to stress and protein folding, such as “response to abiotic stimulus,” “response to osmotic stress,” and “de novoposttranslational protein folding,” were preferentially enriched in DEGs in Cluster 1 (Fig.2-C).DEGs in Cluster 2 were primarily related to the amino acid, carbohydrate, and pyruvate metabolic process (Fig.2-C).For example, zein genes (e.g.,AZ22Z3,AZ22Z4,AZ22Z5, andAZ19D2) and genes encoding the enzymes of the starch biosynthetic pathway (e.g.,GBSSI,SUS1, andSS5) were significantly enriched in Cluster 2.These genes were down-regulated because they could not be induced by defunct O2 in Mo17o2and QPM kernels.

DEGs in Cluster 3 were mainly related to ribosome and protein metabolism, including ribosome biogenesis, ribosome assembly, and cellular protein metabolic process (Fig.2-C).DEGs in Cluster 4 were significantly enriched in GO terms such as protein modification process, the establishment of protein localization, and intracellular protein transport (Fig.2-C).These results demonstrate that the insufficient storage protein synthesis in Mo17o2triggers ribosome biogenesis and protein transport.

According to the Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG; https://www.kegg.jp/) analysis, DEGs in Cluster 1 were primarily related to protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum, fructose, and mannose metabolism and biosynthesis of secondary metabolites; DEGs in Cluster 2 were significantly enriched in terms such as biosynthesis of amino acids, carbon metabolism, and biosynthesis of secondary metabolites; DEGs in Cluster 3 were significantly enriched in terms such as the ribosome, oxidative phosphorylation, and metabolic pathways; DEGs in Cluster 4 were mainly related to spliceosome, DNA replication, endocytosis, and protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum (Fig.2-D).These results demonstrate that both Mo17o2and QPM kernels have altered storage protein accumulation, amino acids, and starch metabolism.

Fig.2 Global transcriptome analysis based on RNA-seq data in 20 days after pollination (DAP) endosperms of Mo17, Mo17o2 mutant, and quality protein maize (QPM).A, shared and unique differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in Mo17o2 vs.Mo17, QPM vs.Mo17, and Mo17o2 vs.QPM.B, the heat map of all DEGs.C, Gene Ontology (GO) classification for DEGs in different clusters.D, significantly enriched Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) terms among the DEGs in different clusters.

3.3.Non-zein proteins enriched lysine, tryptophan, and methionine were up-regulated in Mo17o2 and QPM PBs

To detect the differences in protein abundance in the Mo17o2and QPM endosperm, we used the iTRAQ/TMT method to quantify the non-zein portion of the maize endosperm proteome at 20 DAP.The present study identified 361 813 total spectra, 56 801 peptides, and 7 759 proteins in all samples.Among the 7 759 proteins,2 924 were predicted to be localized in different subcellular compartments; specifically, 658 (22.50%) were predicted to be localized in the nucleus, and 581 (19.87%), 302 (10.33%), 177 (6.05%), and 112 (3.83%) were located in the cytoplasm, cell membrane, endoplasmic reticulum, and Golgi apparatus, respectively (Fig.3-A).Compared with Mo17, 843 and 1 345 DEPs were identified in Mo17o2and QPM, respectively.Notably, Mo17o2and QPM share 44.26% (671) of the same DEPs, including 225 up-regulated DEPs and 446 down-regulated DEPs (Fig.3-B).

GO term enrichment analysis revealed that several protein and carbohydrate metabolism-related GO terms, such as negative regulation of endopeptidase activity, carbohydrate derivative catabolic process, and carbohydrate biosynthetic process, were preferentially enriched in Mo17o2up-regulated DEPs (Fig.3-C).Interestingly, the up-regulated DEPs in QPM had the same enrichment analysis results (Fig.3-C).In addition, several amino acid metabolism-related GO terms, including alpha-amino acid metabolic process and aspartate family amino acid metabolic process, were enriched in both Mo17o2and QPM down-regulated DEPs (Fig.3-C).KEGG terms related to metabolic pathways such as carbon metabolism, starch and sucrose metabolism and glycine, serine and threonine metabolism were enriched in Mo17o2and QPM DEPs (Fig.3-D).These results demonstrate that the accumulation of proteins related to amino acid metabolism, storage protein metabolism, and starch and sucrose metabolism were altered in Mo17o2and QPM kernels.

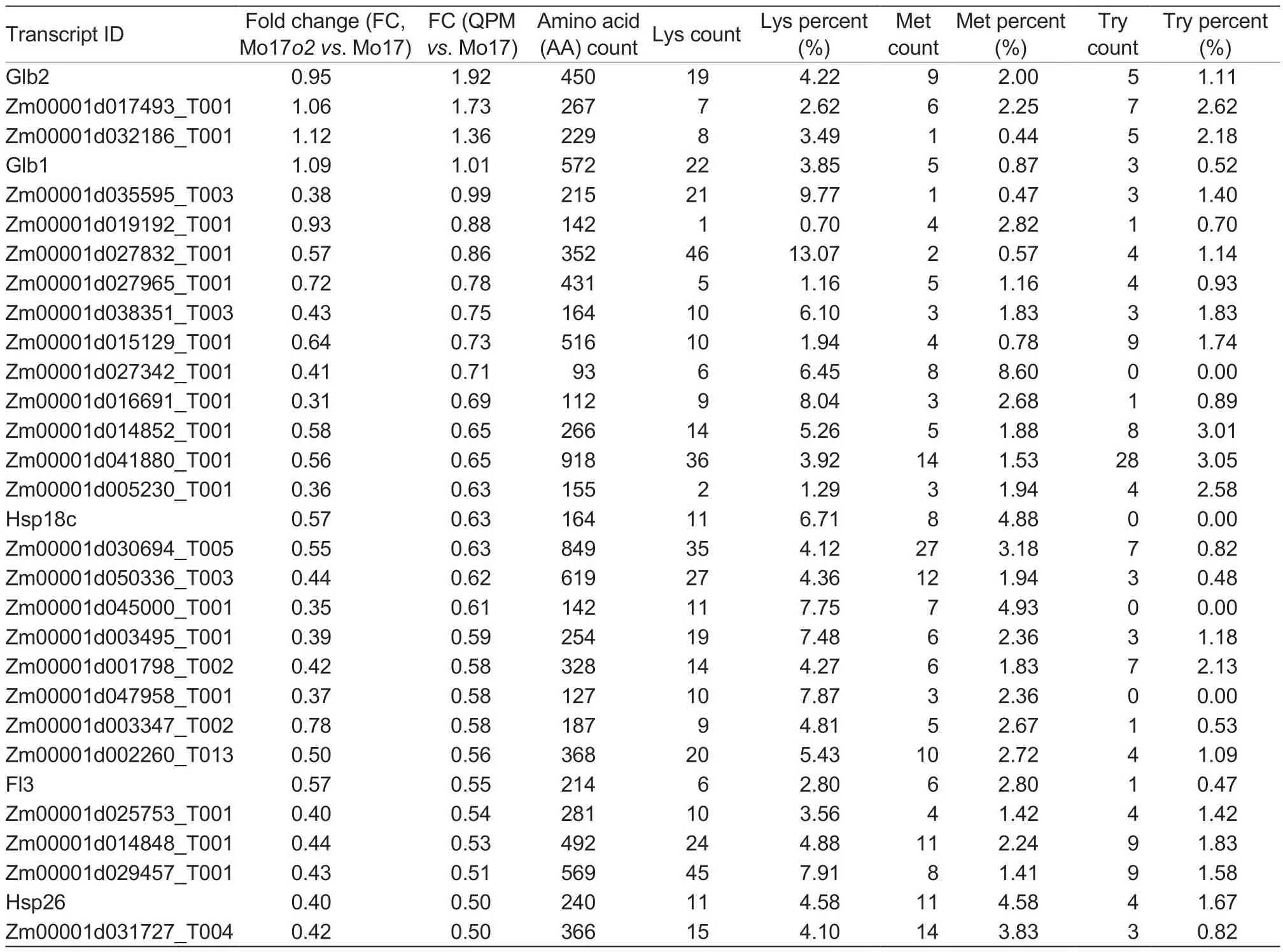

To explore non-zein protein accumulation during endosperm development in Mo17o2and QPM, DEPs in Mo17o2and QPM kernels were compared with the nonzein proteins identified in the proteome of highly purified and intact PBs (Wanget al.2016).Using the proteome of the PBs, we identified 178 proteins that were differentially abundant in Mo17o2and QPM, including 76 up-regulated and 101 down-regulated DEPs in both Mo17o2and QPM, and one protein that was down-regulated in Mo17o2but up-regulated in QPM (Fig.3-E).Some of these DEPs have been reported to be associated with PB filling, including globulins (GLB1, GLB2, and GLB3), heat shock proteins (HSP18C, HSP18F, HSP26, and HSP70-5), Floury3 (FL3), proline responding1 (PRO1), sucrose synthase1 (SUS1), and pyruvate, orthophosphate dikinases (PPDK1 and PPDK2) (Fig.3-F).All of these up-regulated DEPs contain higher amounts of lysine than zeins, especially Zm00001d027832_T001 (13.07%), Zm00001d035595_T003 (9.77%), and Zm00001d016691_T001 (8.04%), and some of these DEPs contain a high percentage of tryptophan or methionine (Table 1).These results suggest that the synthesis of non-zein proteins enriched lysine, tryptophan, and methionine were up-regulated in Mo17o2and QPM PBs, which could be responsible for the increase of lysine, tryptophan, and methionine in Mo17o2and QPM kernels.

Table 1 The percentages of lysine (Lys), tryptophan (Try), and methionine (Met) for the top 30 up-regulated non-zeins in quality protein maize (QPM)

Fig.3 Global proteome analysis based on iTRAQ/TMT data in 20-days after pollination (DAP) endosperms of Mo17, Mo17o2, and quality protein maize (QPM).A, the distribution of predicted subcellular localizations of all detected proteins.B, shared and unique differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) in Mo17o2 and QPM compared with Mo17.C, Gene Ontology (GO) classification for DEPs in Mo17o2 and QPM.D, significantly enriched Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) terms among DEPs in Mo17o2 and QPM.E, Venn diagram comparing the proteins identified from the protein body (PB) sample with the DEPs identified both in Mo17o2 and QPM kernels.F, scatter plot showing proteins shared by the proteins identified from the PB sample and the DEPs identified both in Mo17o2 and QPM.

3.4.The processes of amino acids, storage protein, starch, and sucrose metabolism were affected in Mo17o2 and QPM kernels

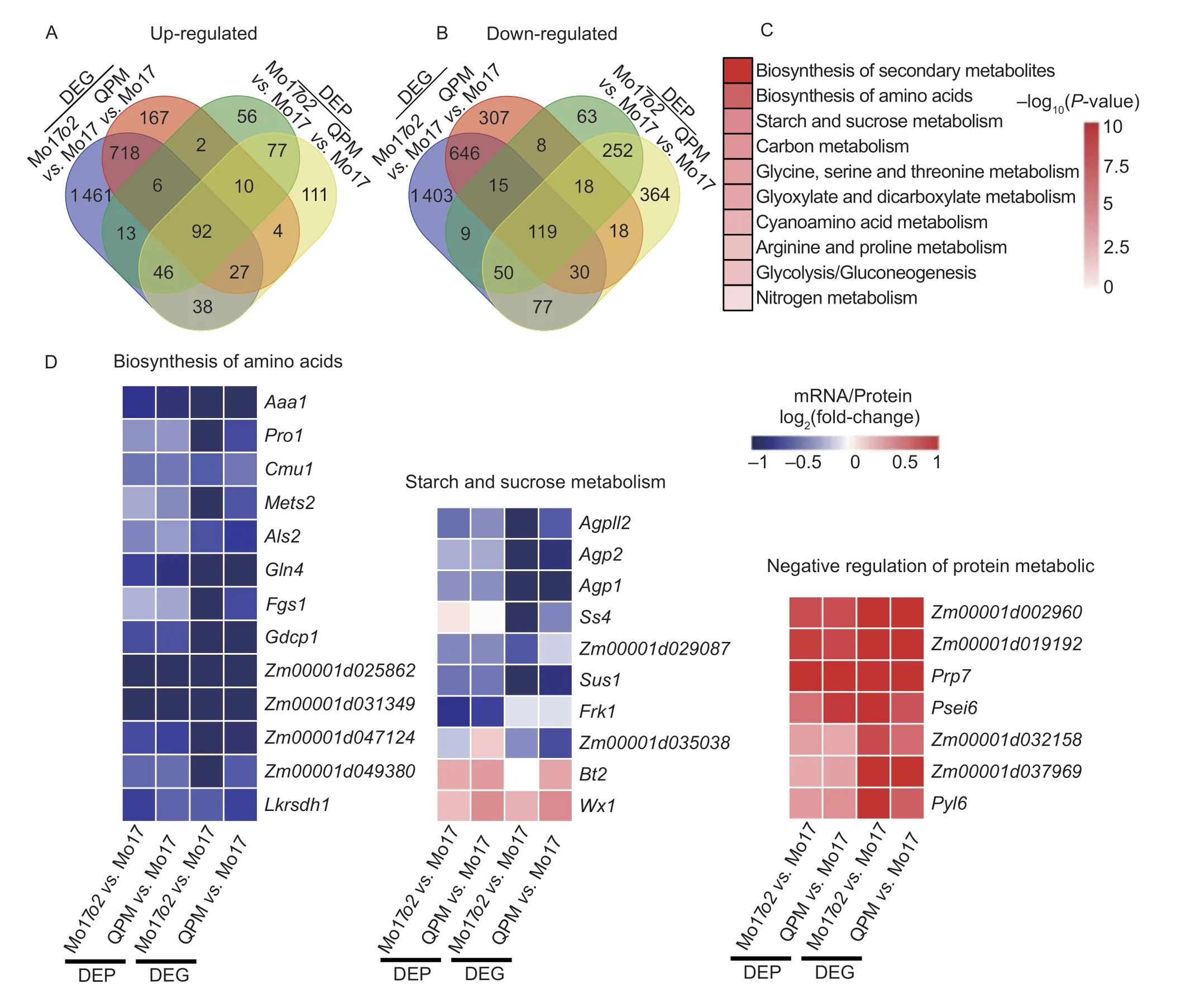

Changes in transcript levels could reflect the protein rebalancing in Mo17o2and QPM kernels.Therefore, we compared the DEGs and DEPs in Mo17o2and QPM.We found 92 genes up-regulated at the transcript and protein levels, includingGLB1andGLB2.Further enrichment analysis suggested that these genes were associated with negative regulation of the protein metabolic process (Fig.4-A; GO: 0051248,P-value=4.5e–06).We found that 119 genes shared by the DEGs and DEPs were down-regulated in either Mo17o2or QPM (Fig.4-B), and they were mainly enriched in KEGG terms related to starch and sucrose metabolism and biosynthesis of amino acids, such as glycine, serine, threonine, arginine, and proline (Fig.4-B and C).We found a weak correlation between the transcriptome and proteome in up- or downregulated genes (Fig.4-A and B).This finding suggests that proteomics data better capture the process of storage protein rebalancing than transcriptome data.

We observed that in the biosynthesis of the amino acids pathway,adenosylmethionineaminotransferase1(Aaa1),prolineresponding1(Pro1),chorismatemutase1(Cmu1),methioninesynthase2(Mets2),acetolactatesynthase2(Als2),glutaminesynthetase4(Gln4),ferredoxin-dependentglutamatesynthase1(Fgs1),glycinedecarboxylase1(Gdcp1), andlysine-ketoglutaratereductase/saccharopinedehydrogenase1(Lkrsdh1) were down-regulated at both the transcript and protein levels in Mo17o2and QPM (Fig.4-D).Meanwhile,cystatin6(Psei6),pathogenesis-relatedprotein7(Prp7), andpyrabactinresistance-like6(Pyl6) were up-regulated at both the transcript and protein levels in Mo17o2and QPM kernels.These proteins were annotated as being involved in the negative regulation of protein metabolism (Fig.4-D).The enzymes such as glycogen synthase, glucose-1-phosphate adenylyltransferase, and NDPglucose-starch glucosyltransferase are associated with starch synthesis (Fig.4-D).Glucose-1-phosphate adenylyltransferases are encoded by 11 paralogous genes in maize.Our data revealed thatADPglucosepyrophosphorylaselargesubunitleaf2(Agpll2) andADPglucosepyrophosphorylasesmallsubunitembryos(AGP1andAGP2) were down-regulated at both the transcript and protein levels, andBt2was up-regulated at both the transcript and protein levels (Fig.4-D).Ss4, encoding glycogen synthase, was down-regulated in Mo17o2at the transcript level but not at the protein level.Wx1encoding NDP-glucose-starch glucosyltransferase was up-regulated in Mo17o2and QPM kernels at the protein and transcript level (Fig.4-D).In the sucrose degradation pathway, the transcript level and/or protein level of the enzymes sucrose synthase (SUS1andZm00001d029087) and fructokinase (Frk1andZm00001d035038) were altered in Mo17o2and QPM kernels (Fig.4-D).These results generally indicated that the processes of amino acids biosynthesis, storage protein metabolism, and starch and sucrose metabolism were affected in Mo17o2and QPM kernels.

Fig.4 Integrated analysis of transcriptomics and proteomics data.A, Venn diagram comparing up-regulated differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and differentially expressed proteins (DEPs).B, Venn diagram comparing down-regulated DEGs and DEPs.C, significantly enriched Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) terms among down-regulated DEGs and DEPs.D, log2(fold-change) heat maps of DEGs and DEPs functioning in influenced pathways in Mo17o2 and quality protein maize (QPM).

3.5.Identification of regulators and companions associated with storage protein synthesis in maize

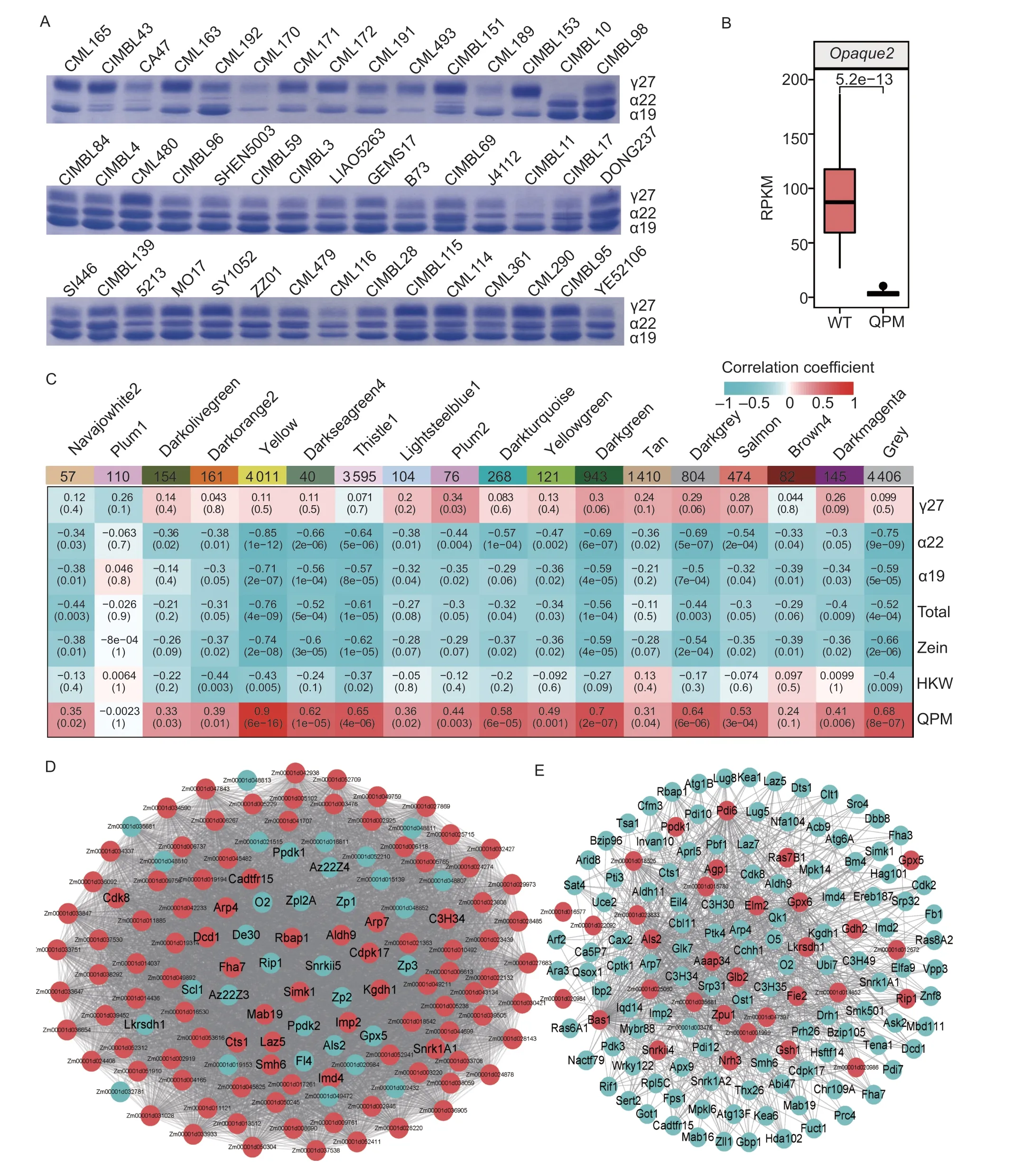

In order to identify regulators and companions associated with storage protein synthesis in maize, we selected a large population containing 13 QPM lines and 32 normal protein maize inbred lines from a diverse panel of inbred lines (Fuet al.2013; Liet al.2013).These QPM inbred lines accumulated a lower level of 19-kDa α-zein protein, and the levels of 22-kDa α-zein protein were almost undetectable (Fig.5-A); these phenotypes are the same as in Fig.1-B.The expression ofO2cannot be detected in these QPM inbred lines (Fig.5-B).These results confirmed that the QPM and normal protein maize inbred lines we selected are representatives of the typical QPM and normal protein maize phenotypes.

A total of 77 genes that were differentially expressed at both mRNA and protein levels in Mo17o2and QPM were also present in the differentially expressed genes between QPM and normal maize inbred lines (Student’st-test,P<0.01), including nine down-regulated and 68 upregulated genes in the QPM inbred lines (Appendix F).For example,Ppdk1is a well-documented O2 target gene participating in the glycolytic pathway, regulating carbon and amino acid metabolism by converting pyruvate to phosphoenol pyruvate (Zhanget al.2016).In our data,Ppdk1was down-regulated at the transcript and protein levels in the QPM inbred lines (Fig.3-F; Appendix F).Meanwhile, the expression of three starch biosynthetic genes,Agp1,Agp2, andZpu1, was up-regulated in the QPM inbred lines (Fig.3-F).The QPM inbred lines showed up-regulation of five genes encoding amino acid metabolic enzymes, namelyaspartyl protease3(Aed3),beta alanine synthase1(Bas1),glutamic dehydrogenase2(Gdh2),gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase1(Gsh1), andlysine-ketoglutarate reductase/saccharopine dehydrogenase1(Lkrsdh1).This finding suggests that the synthesis of several types of amino acids has changed in QPM kernels, which corresponded to the protein rebalance in QPM inbred lines (Appendix F).α-Globulin is a typical non-zein for kernel storage proteins; the gene encoding globulin2 (Glb2) was up-regulated in the QPM inbred lines and up-regulated in Mo17o2and QPM lines at the transcript and protein levels (Fig.3-F).Furthermore, a number of genes with unknown functions were up- or down-regulated in the QPM inbred lines (Appendix F).

In order to identify candidate hub genes correlated to storage protein synthesis in maize, we used WGCNA to determine which highly connected nodes in the expression networks are associated with storage protein rebalancing.A total of 17 001 genes were retained for the constructed co-expression network (average RPKM greater than 1 and the maximum RPKM greater than 6 in our selected inbred lines), and 18 distinct modules were identified based on the pairwise correlations of gene expression levels across all samples when the soft-thresholding power was set as 14 (Fig.5-C).These modules were labeled in different colors.The “yellow” module showed a significant and positive correlation with the QPM phenotype (r=0.9,P-value=6e?16) but significant and negative correlations with 22 kDa α-zein (r=–0.85,P-value=1e?12), 19 kDa α-zein (r=–0.71,P-value=2e?7), all zeins (r=–0.74,P-value=2e?8), and total storage protein (r=–0.76,P-value=4e?9) (Fig.5-C).These findings corresponded to the suppressed expression of 19- and 22-kDa α-zeins in QPM.

Fig.5 Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) of the transcripts in the quality protein maize (QPM) and normal protein maize inbred lines.A, SDS-PAGE analysis of zein proteins in different QPM and normal protein maize inbred lines.B, relative expression of O2 in the QPM inbred lines relative to normal protein maize lines.C, module-trait heatmap displaying the correlation between the eigengene of all modules and traits.D, network analysis of O2 in the yellow module (red: gene and Module Membership>0; cyan, gene and Module Membership<0).E, network analysis of these genes detected as differentially expressed protein (DEP) and DEG in Mo17o2 and QPM kernels in the yellow module (red, DEPs; cyan, regulators and companions).HKW, hundred-kernel weight.

A total of 3 898 genes with edge weight>0.10 were assigned to the “yellow” module, and 132 co-expressed genes showing a high node connectivity in this module were regarded as hub genes (Fig.5-D), which could be associated with the process of storage protein rebalancing in QPM.Surprisingly,O2and seven α-zein genes were identified as hub genes with negative module membership (MM) in this module, which corresponded to the fact thatO2and the α-zeins were down-regulated in QPM (Fig.5-D).Ppdk1andPpdk2were found in the “hub genes”; meanwhile, transcriptomic and proteomic analysis revealed that they were down-regulated in Mo17o2and QPM kernels at the transcript and protein levels (Figs.5-D and 3-F).These “Hub genes” are associated with the phenotype of QPM (Geethaet al.1991; Liuet al.2016; Zhanget al.2016).Moreover, genes encoding three different transcription factor family members (i.e.,C3H-transcriptionfactor334(C3H34),CCAAT-DR1-transcriptionfactor15(Cadtfr15), andFHA-transcriptionfactor7(Fha7) and several unannotated proteins were identified as hub genes (Fig.5-D).

A total of 32 genes that were differentially expressed at both protein and mRNA levels in Mo17o2and QPM were detected in the “yellow” module, includingZpu1,Ppdk1,Glb2, andAgp1(Fig.5-E).Meanwhile, 28 hub genes identified in this module (e.g.,O2,C3H34,Als2, andLkrsdhl) were co-expressed with these DEPs (Fig.5-E).Opaque5(MGD1),Smallkernel501(smk501;E1C-TERMINALRELATED1),Prolamine-boxbindingfactor1(Pbf1), four C3H-transcription factors (C3H30,C3H34,C3H35, andC3H49), two bZIP-transcription factors (Bzip105andBzip96), two FHA-transcription factors (Fha3andFha7), and genes with predicted functions were co-expressed with these DEPs (Fig.5-E).These genes may act as regulators or companions associated with storage protein rebalancing in QPM.

4.Discussion

4.1.The process of storage protein rebalancing was better captured by the proteomic data

This study performed transcriptomic and proteomic analyses in Mo17o2and QPM kernels to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of storage protein rebalancing between zein and non-zein proteins.Our results revealed a weak correlation between the transcriptome and proteome, consistent with previous reports (Liet al.2020; Heet al.2021).Most of these non-correlative discrepancies between proteome and transcriptome are manifestations of post-transcriptional and post-translational modifications, and therefore, large overlaps between these datasets should not be expected.Meanwhile, the limited overlap highlights the advantage of parallel proteomic and transcriptomic studies for comprehensively understanding the storage protein rebalancing in maize endosperm.The DEGs only detected in Mo17o2were a large percentage of total DEGs (61.7%) (Fig.2), corresponding to the decreased PB organization and the chalky endosperm development in theo2mutant (Mertzet al.1964; Zhanget al.2016), however, the DEPs identified in Mo17o2and QPM kernels were highly consistent (Fig.3).The inconsistency between DEGs and DEPs can be attributed to the higher sensitivity of mRNA detection compared to protein (Kumaret al.2016; Tanget al.2021).These results demonstrated that the proteomics data provide an enhanced understanding of the process of storage protein rebalancing.

4.2.The molecular mechanisms involved in the storage protein rebalance in Mo17o2 and QPM

Phenotypic observations and transcriptomic studies of maize starch endosperm mutants and QPM generally conclude that the synthesis of zein protein is reduced while that of non-zein proteins is increased in these germplasms (Geethaet al.1991; Myerset al.2011; Wanget al.2014b; Liet al.2017).We revealed the details of this process using parallel proteomic and transcriptomic studies, finding that only a few non-zein proteins were affected in Mo17o2and QPM, and less than half were up-regulated (Fig.3-E).Most up-regulated non-zein proteins identified in Mo17o2and QPM were enriched in lysine, tryptophan, and methionine (Table 1), resulting in increased protein quality in Mo17o2and QPM.This result was consistent with the selective accumulation of lysine-enriched proteins in most maize opaque endosperm mutants (Mortonet al.2016).Meanwhile, we found that the accumulation of these proteins increased more in QPM than in Mo17o2(Table 1), which could be attributed to the fact that gene duplication ofqγ27enhanced the accumulation of non-zein proteins in QPM.KEGG pathways such as nitrogen metabolism, protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum, and numerous amino acid metabolism were highly enriched in DEPs and DEGs.Storage proteins are stored in PB, and PB is assembled by the endoplasmic reticulum.Therefore, the endoplasmic reticulum is essential for the synthesis of storage proteins (Holdinget al.2007; Wanget al.2014a).Differential expression of multiple endoplasmic reticulumassociated genes and proteins could impact the synthesis of storage proteins.Several enzymes involved in lysine, proline, methionine, glutamine, and glutamate metabolism were down-regulated in the QPM kernels at both the transcript and protein levels (Fig.4-D).These includeLkrsdh1involved in the lysine degradation pathway, which was down-regulated at both the transcript and protein levels in Mo17o2and QPM kernels, thereby inhibiting lysine degradation (Kemperet al.1999; Kawakatsu and Takaiwa 2010).Amino acids make up protein, and a deficiency of amino acids is fatal for protein synthesis.For example, proline deficiency downregulates storage protein synthesis and significantly reduces the number and size of PB (Wanget al.2014b).Conclusively, protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum and amino acid metabolism appears pivotal to controlling the storage protein rebalance in Mo17o2and QPM.

4.3.Fl3, Pro1, and α-globulins could be involved in storage protein synthesis in QPM

Interestingly, our analysis detected Fl3 as a DEP in Mo17o2and QPM kernels.Fl3has been shown to control storage protein synthesis in maize kernels, and an amino acid replacement in the PLATZ domain of this protein led to defects in PB synthesis and endosperm starch composition (Liet al.2017).Pro1was down-regulated in Mo17o2and QPM kernels at both the transcript and protein levels, and it has been shown to be involved in the biosynthesis of proline from glutamic acid; the loss ofPro1function significantly decreases proline accumulation and general protein synthesis, resulting in an opaque kernel phenotype (Wanget al.2014b).α-Globulins are important storage proteins in cereal kernels (Shewry and Halford 2002).In this study, three α-globulins (GLB1, GLB2, and GLB3) were up-regulated in Mo17o2and QPM kernels at the protein level.Previous studies showed thatGlb3is co-deposited with 27-kDa γ-zein to stimulate storage protein synthesis (Zhanget al.2020).Meanwhile, all of these proteins were detected in PBs, suggesting that these proteins could be involved in storage protein synthesis in QPM.

4.4.Hub genes associated with storage protein rebalance

Previous studies have used transcriptomics to uncover the signaling pathways of starch and zein proteins accumulated in theo2mutant.They found thatO2regulates 19- and 22-kDa α-zein genes,Ppdk1, andPpdk2(Liet al.2015; Zhanget al.2016; Zhanet al.2018).WGCNA revealed thatO2and severalO2targets act as hub genes in the co-expression network, including 19 kDa α-zein genes (Zp1,Zp2,Zp3,Fl4,Zpl2A, andDe30), 22 kDa α-zein genes (Az22Z3andAz22Z4),Ppdk1, andPpdk2.The 19- and 22-kDa α-zein genes control zein protein accumulation (Guoet al.2013);Ppdk1andPpdk2participate in starch biosynthesis, which is responsible for storage protein rebalancing in QPM (Zhanget al.2016).Meanwhile,Lkrsdh1,Als2,Gpx5,Rip1,Zm00001d020984, andZm00001d035681acted as hub genes in the yellow module and showed significantly different expression in Mo17o2and QPM kernels at the transcript and protein levels.Moreover, 21 hub genes identified in the yellow module were coexpressed with these genes, which were identified as DEPs and DEGs in both Mo17o2and QPM kernels, includingO2,aldehydedehydrogenase9(Aldh9), andC3H34.It is worth noting thatO5,Pbf1,Zpu1, three C3H-transcription factors (C3H30,C3H35, andC3H49), and two bZIP-transcription factors (Bzip96andBzip105) were co-expressed with these genes.Previous studies reported thatO5is responsible for the synthesis of galactolipids to control starch grain production and endosperm development (Myerset al.2011);Pbf1acts additively withO2to affect starch and protein synthesis in maize kernels (Zhanget al.2016);Zpu1regulates starch synthesis by affecting pullulanase-type starchdebranching enzyme activity (Beattyet al.1999).The present study identified several hub genes in the network of storage protein synthesis.Some of them were coexpressed with non-zein proteins, which potentially regulate storage protein rebalance or act as non-zein proteins in PBs.Further examination is necessary to determine whether it is a false positive.

5.Conclusion

Our results demonstrated that QPM’s storage protein rebalancing process was more similar to Mo17o2at the translational level.At the same time, a significant difference still existed at the transcriptional level.Many DEPs and DEGs identified in Mo17o2and QPM were associated with starch and sucrose metabolism, amino acid biosynthesis, and protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum.Some of these DEPs act as nonzeins and participate in the process of PB organization, such asFL3,PRO1, andGlb3.In addition, we identified several non-zeins up-regulated in QPM with high percent lysine, which could be responsible for the increased level of the essential amino acids lysine, tryptophan, and methionine in QPM.We verified these DEPs using the transcriptome data in 13 QPM and 32 normal protein maize inbred lines.We also identified regulators and companions associated with storage protein rebalancing in QPM.Overall, this study provides new information about the QPM proteome and transcriptome to understand the molecular mechanisms of the storage protein rebalancing.The up-regulated non-zein proteins and their regulators identified in QPM contribute to understanding the genetic basis of storage protein rebalancing in QPM, facilitating better QPM breeding.A promising future research direction is to functionally validate non-zein proteins and their regulators and manipulate them to improve protein quality in maize kernels using modern biotechnologies.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31971951 and 31771796).The computations in this paper were run on the bioinformatics computing platform of the National Key Laboratory of Crop Genetic Improvement, Huazhong Agricultural University.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendicesassociated with this paper are available on https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jia.2022.08.031

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年5期

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年5期

- Journal of Integrative Agriculture的其它文章

- Herbicidal activity and biochemical characteristics of the botanical drupacine against Amaranthus retroflexus L.

- Developing a duplex ARMS-qPCR method to differentiate genotype l and ll African swine fever viruses based on their B646L genes

- The effects of maltodextrin/starch in soy protein isolate–wheat gluten on the thermal stability of high-moisture extrudates

- Elucidation of the structure, antioxidant, and interfacial properties of flaxseed proteins tailored by microwave treatment

- Effects of planting patterns plastic film mulching on soil temperature, moisture, functional bacteria and yield of winter wheat in the Loess Plateau of China

- lnversion tillage with straw incorporation affects the patterns of soil microbial co-occurrence and multi-nutrient cycling in a Hapli-Udic Cambisol