Polycystic ovary syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus: A state-oftheart review

INTRODUCTION

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) constitutes the most common endocrine disorder in women of reproductive age, affecting 6%-15% of the of the global population[1]. PCOS is a multifaceted, ever-changing disease and a challenging disorder for the caring physician due to the continuous need for treatment modifications and adjustments based on the patient’s fluctuating needs and preferences throughout the course of her lifetime. Apart from oligo- or amenorrhea and/or clinical or biochemical hyperandrogenism, impaired glucose homeostasis has also been observed in patients with PCOS[1,2]. In particular, evidence from large prospective cohorts has shown progression to either prediabetes or type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) over time[3,4]. The emergence of T2D in PCOS can be anticipated to some extent given that the two prerequisites for T2D development, insulin resistance (IR) and ?-cell dysfunction, are frequently present in women with PCOS. Indeed, IR, which is a key player in underlying PCOS pathophysiology, has been documented in the vast majority of women suffering from the syndrome in comparison to their healthy body mass index (BMI)-matched peers. An additive effect of obesity on the degree of IR reported in these women should also be taken into account[5]. Meanwhile, the prevalence of pancreatic ?-cell dysfunction is much higher in these patients compared to their regularly ovulating, non-hyperandrogenic peers[6].

Miss White was a smiling, young, beautiful redhead, and Steve was in love! For the first time in his young life, he couldn’t take his eyes off his teacher; yet, still he failed. He never did his homework, and he was always in trouble with Miss White. His heart would break under her sharp words, and when he was punished for failing to turn in his homework, he felt just miserable3! Still, he did not study.

Nevertheless, there is an ongoing debate as to whether PCOS itself constitutes a risk factor for T2D or whether T2D predominantly occurs in the context of obesity in affected patients[7-9]. A recent meta-analysis of genetic studies suggests that there is no inherent T2D risk in PCOS and that T2D instead occurs as a result of either increased adiposity or hyperandrogenemia[10]. On the other hand, PCOS constitutes a polygenic trait and elegant studies have shown that clusters of genes leading to metabolic disturbances are different from those associated with overt hyperandrogenic signs in PCOS women[11]. Therefore, a genetic component of dysglycemia among PCOS women should be considered.

The presence of altered glycemic status, although a universal finding, is challenging to the clinician for several reasons. One is that the reported incidence of dysglycemia, which includes impaired fasting glucose (IFG), impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), and T2D, varies among studies. Furthermore, agreement over a definitive recommendation regarding the optimal method for assessment of glycemic status has not been reached to date.

The aim of this narrative review was to provide the most current knowledge on the different aspects of T2D in women with PCOS, including epidemiology, common pathophysiologic mechanisms, and methodology employed for dysglycemia assessment, as well as to scrutinize the risk factors for T2D development and to suggest the optimal management of these women in the context of T2D risk reduction.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF DYSGLYCEMIA IN PCOS

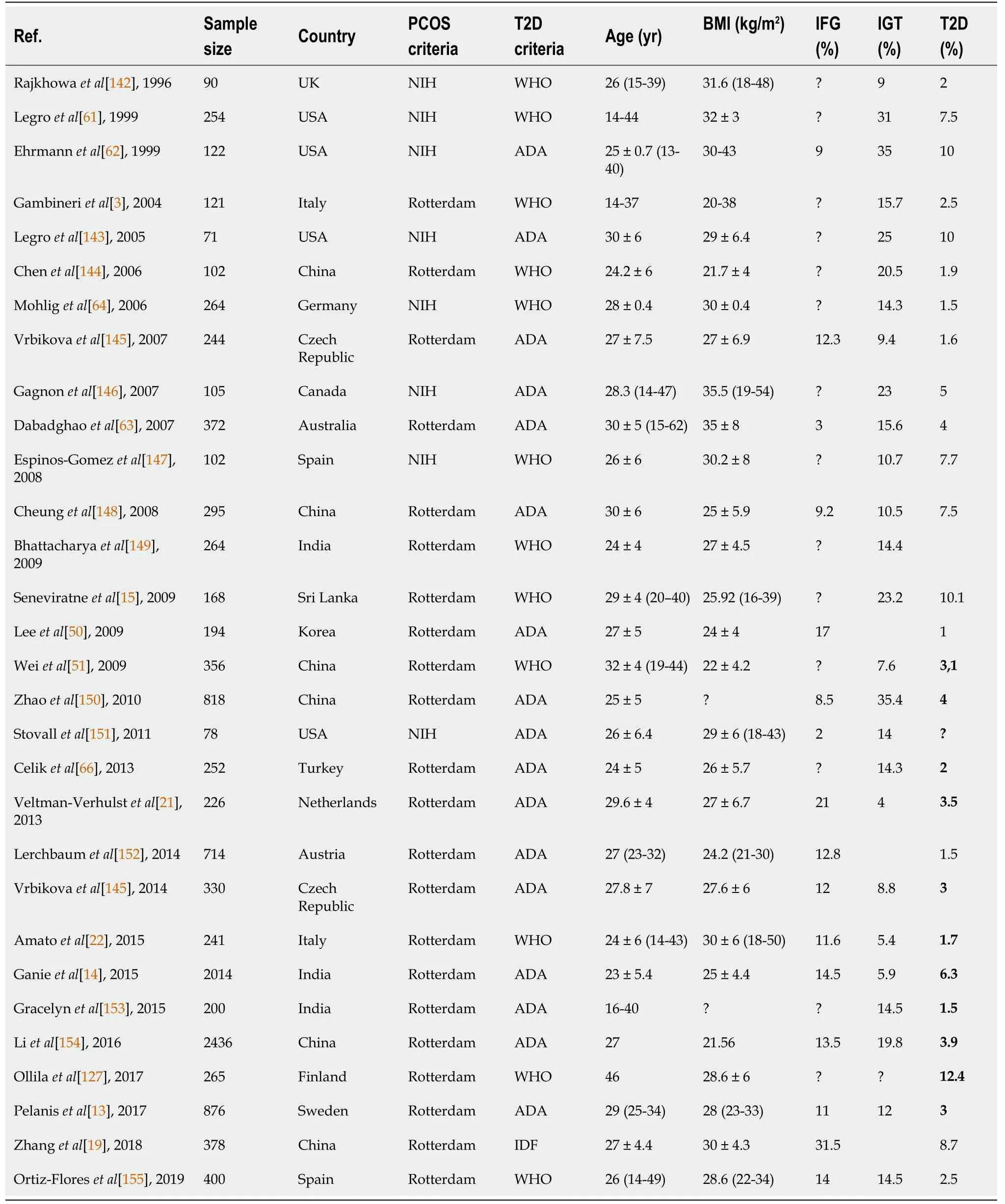

In general, the prevalence of dysglycemia is significantly higher in women with PCOS compared to their healthy BMI-matched peers. With regard to T2D, in normal women of reproductive age, the mean prevalence of T2D is 1%-3%[12], whereas in PCOS, its prevalence ranges from 1.5 to 12.4%, with a median value of 4.5%. This wide range partly depends on the age of the studied subjects, with the higher incidence (12.4%) recorded in a study evaluating mostly perimenopausal women with PCOS and a mean age of 46 years[13]. In the remaining studies, the mean age of the studied population ranged from 25 to 30 years. Another factor closely associated with T2D prevalence is ethnic variation, since a prevalence of 6.3% and 10.1% has been reported in two studies from Asia[14,15], reflecting the rising prevalence of T2D in Asia[16], a trend that has recently been corroborated in a large meta-analysis[17]. Finally, one more factor pertains to the criteria applied for PCOS diagnosis. For example, a higher degree of dysglycemia is anticipated in women diagnosed with the 1991 National Institutes of Health (NIH) criteria in comparison with the mild phenotype D of those diagnosed with the 2003 Rotterdam criteria, this due to the lower degree of IR observed in the latter group[18]. On the other hand, this logical assumption was not confirmed by a recent study evaluating more than 2000 women, which showed that T2D prevalence was similar among patients with different PCOS phenotypes[19].

Fifty years ago there lived a king who was very anxious to get married; but, as he was quite determined1 that his wife should be as beautiful as the sun, the thing was not so easy as it seemed, for no maiden2 came up to his standard

In addition, women with PCOS present with enhanced luteinizing hormone pulsatility, producing increased secretion of ovarian and adrenal androgens, which, along with IR, are key features of the syndrome. A meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies including 4795 women from the general population found higher testosterone concentrations in patients with T2D compared to controls[32]. In addition bioavailable testosterone correlated significantly with IR, with higher concentrations predicting the development of T2D[33]. Similar results were obtained from a systematic review and meta-analysis pooling data from the Rotterdam Study and other previously published studies, which found that subjects at the highest tertile of free androgen index had a 42% higher risk of developing T2D, in a complex multivariate analysis controlling, among others, for age, BMI, glucose, and insulin concentrations[34].

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY LINKING PCOS WITH INCREASED RISK OF T2D

PCOS pathophysiology is characterized by a combination of androgen excess and ovulatory dysfunction. Although numerous studies have endeavored to identify the underlying pathogenetic mechanisms, this particular ‘Holy Grail’ of endocrinology has not as yet been uncovered. Irrespective of the theoretical perspective, it is widely accepted that the unusually variable phenotype in affected patients is produced by the combined effects of two separate, yet deeply intertwined, mechanisms, which are androgen over-activity (elevated androgen concentrations or hyperandrogenism) and IR[23].

When the birds began to sing he could lie still no longer, and climbed out of his window into the branches of one of the great lime-trees that stood before the door

IR represents a state of disrupted insulin binding to its receptor or ineffective activation of the latter by insulin, thereby forcing the pancreatic β-cells to release large amounts of insulin into the circulation in order to maintain euglycemia[24]. Such a state of chronic pancreatic stress leads to impaired glucose homeostasis, initially manifesting as IFG or IGT; however, once large numbers of islet β-cells have succumbed to stress, it leads to T2D. IR and glucose homeostasis abnormalities have been described in up to 70% of women with PCOS[25]. As early as 1980, eight obese subjects with PCOS were found to have higher serum glucose and insulin concentrations, in both a fasting state and after stimulation by an oral glucose load, compared with six obese unaffected women, despite the latter being statistically significantly more obese[26]. Even though obesity is a key risk factor for IR and T2D development in the general population, women with PCOS have higher insulin concentrations in response to an oral glucose load as compared to unaffected subjects, even in the absence of obesity[27,28]. The only clinical sign of IR is acanthosis nigricans, which correlates well with IR in either obese or lean affected individuals[29].

Of course, women with PCOS are equally exposed to the well-established association of obesity and higher degree of IR as those without PCOS. Indeed, a study comparing 198 obese and 201 non-obese women with PCOS (obesity definition: BMI > 27 Kg/m

) found that obesity was associated with lower insulin sensitivity when a variety of oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)-derived indices was used[30]. In contrast to the latter findings, a study employing the impractical gold standard method to assess IR, namely, the hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp, it found more pronounced insulin secretion in lean women with PCOS compared to controls, though without significant differences in insulin sensitivity, while it confirmed the presence of higher IR compared to controls only in obese women with PCOS[31].

Several years later, young Tom was rummaging1 around in the garage as only a five- or six-year-old can rummage2 when he came across the all-leather, NFL regulation, 1963 Chicago Bears-inscribed football. He asked if he could play with it. With as much logic3 as I felt he could understand, I explained to him that he was still a bit too young to play carefully with such a special ball. We had the same conversation several more times in the next few months, and soon the requests faded away.

Indisputably, the impact of environmental factors on T2D development is major. Endocrine disruptors constitute an emerging environmental threat, and a role for endocrine disrupting chemicals in exacerbating PCOS pathology has been proposed for over 20 years, with bisphenol A (BPA) being significantly associated with measures of IR and BMI in women with the syndrome[88]. Moreover, a positive feedback loop between BPA and hyperandrogenemia has been shown in PCOS and, therefore, BPA exposure has been particularly incriminated in PCOS pathophysiology[89]. Furthermore, the role of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) in the pathophysiology of T2D development in PCOS is another issue that has gained ever more attention over time. AGEs are products of non-enzymatic glycation and oxidation (glycoxidation) of proteins and lipids in both hyperglycemic and euglycemic states. Thermally processed foods, mostly lipid- and protein-rich foods typical of Western diets, are responsible for the exceedingly high intake of exogenous AGEs, these remaining in the body and being incorporated covalently in different tissues. Dietary AGEs have been associated with subclinical inflammation and endothelial dysfunction both in patients with T2D and in unaffected individuals[90]. Of interest, concentrations of AGEs are elevated in women with PCOS compared to their healthy counterparts independently of the degree of obesity and IR[91]. They are positively associated with androgens and anti-Müllerian hormone levels and are localized in human polycystic ovaries. Based on all the above, a potential role of AGEs in the PCOS machinery has been suggested[90]. In women with PCOS, consumption of a diet high in AGEs was followed by a deterioration of IR and hyperandrogenemia, whereas elimination of AGEs was followed by a significant amelioration of these key parameters, even without a change in BMI[92]. On the other hand, the link of endocrine disruptors with human pathophysiology should be interpreted with caution, since their actions are exerted in an non-monotonic pattern[93].

Despite the similar pathophysiology of PCOS and glucose homeostasis abnormalities, the differences between lean and obese women with PCOS are remarkable. This was shown by a recent study in which lean women with PCOS failed to improve their whole body insulin action, measured using a hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp after 14 wk of controlled and supervised exercise training, in contrast to controls[46]. Therefore, it came as no surprise when a recent meta-analysis of 13 studies including almost 279000 subjects identified a markedly elevated risk for T2D among women with PCOS compared to unaffected women [5.9%

2.0%; relative risk (RR): 3.00, 95%CI: 2.56-3.51;

= 83%][47]. Similar results were found

a meta-analysis recently presented by our group: in this systematic review, 23 studies were lumped together, incorporating data from 319870 participants who comprised 60337 patients with PCOS and 8847 cases with T2D (RR: 3.45, 95%CI: 2.95-4.05). In our study, the effect of BMI on the risk of T2D was assessed, pooling data from three studies, which identified a pronounced effect of obesity. In particular, the RR for developing T2DM in overweight/obese and non-obese women with PCOS, as compared to their non-PCOS counterparts, was 5.75 (95%CI: 1.20-27.42) and 3.34 (95%CI: 0.03-400.52), respectively. Moreover, the RR for developing T2D in overweight/obese compared to lean women with PCOS was 3.96 (95%CI: 1.22-12.83)[48].

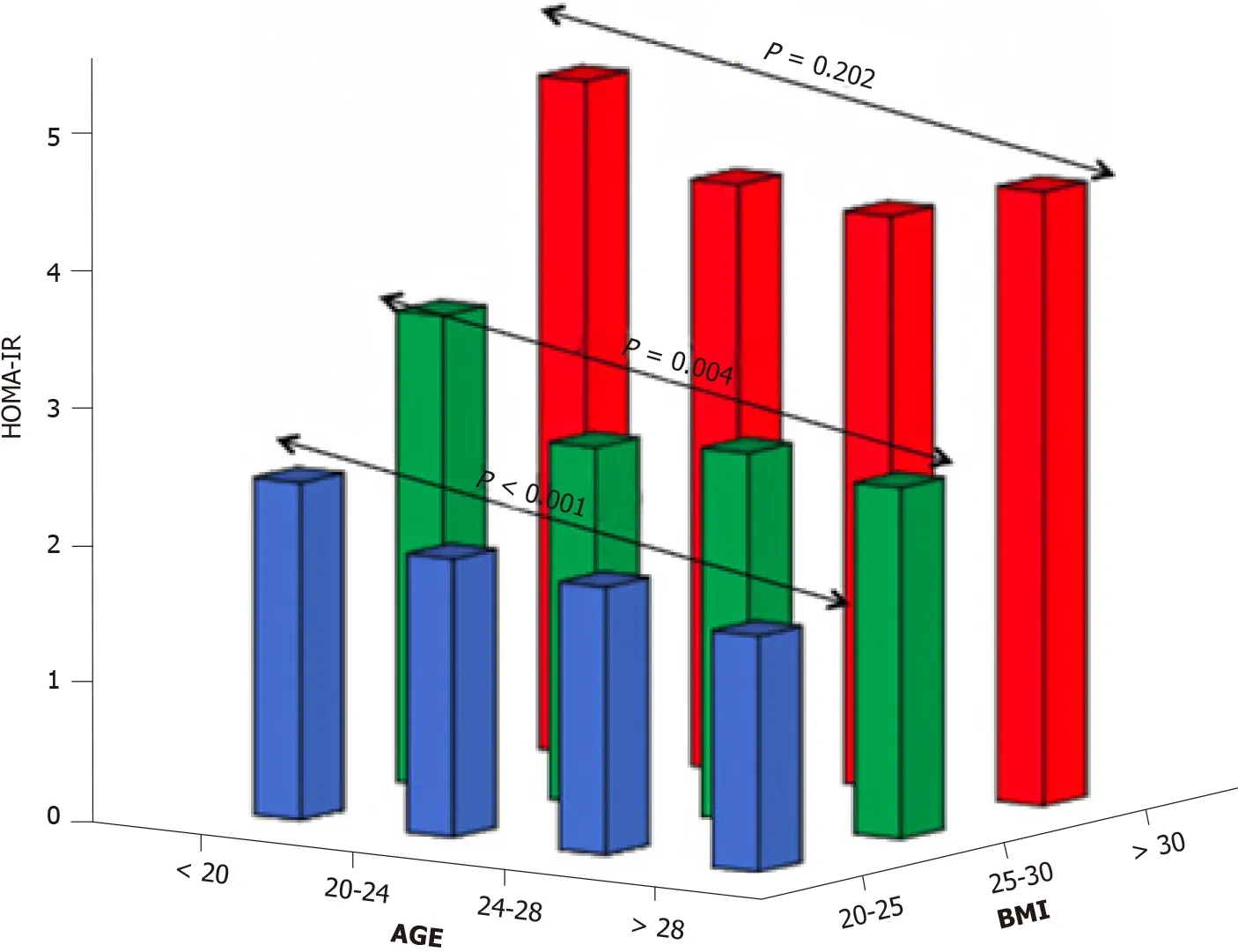

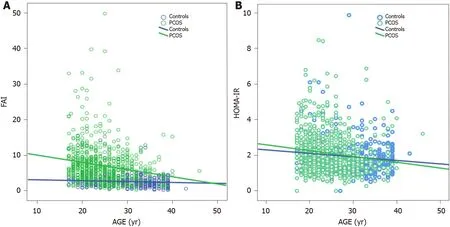

Meanwhile, the role of aging in T2D development should certainly not be underestimated. This has been demonstrated in, inter alia, a subgroup analysis of 345 Dutch women with PCOS, who were part of a large cohort study evaluating aging in women with PCOS (APOS study)[49], where the interaction of age and BMI was the most significant variable in predicting T2D in logistic regression analysis. Moreover, data assembled from several studies have also pointed to a positive association of age and BMI with T2D or intermediate hyperglycemia among women with PCOS[19,50,51]. On the other hand, a cross-sectional study conducted by our group found that aging might exert a protective effect in women with PCOS with regard to IR. In particular, obese women with PCOS demonstrated the same degree of IR through the years, although this was not the case for their lean peers in whom a gradual improvement was observed with aging (Figure 1)[52]. Furthermore, a large cross-sectional study (

= 763 normal-weight women with PCOS, according to the Rotterdam criteria; 376 controls) exhibited a parallel decrease of homeostasis insulin resistance assessment (HOMA-IR) index with free androgen index, suggesting a potential mechanism regulating this process (Figure 2)[53]. Specifically, the gradual reduction of androgen production observed in women with PCOS after their third decade of life partly explains the absence of deterioration of IR through the years which is common in the general population.

ASSESSMENT OF DYSGLYCEMIA IN PCOS

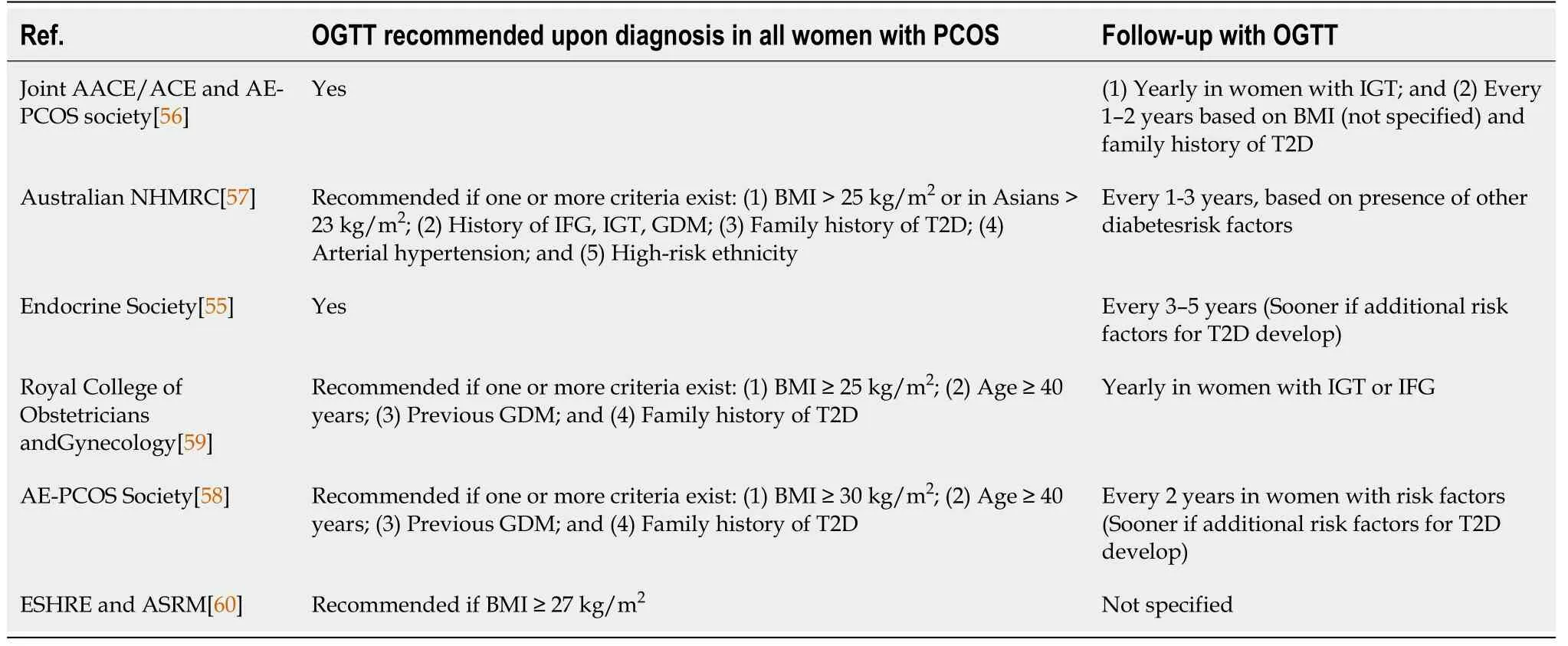

According to the Wilson and Jungner criteria, screening for a disease is essential when that condition constitutes an important health problem, an accepted treatment for patients with recognized disease exists, and facilities for diagnosis and treatment are available. Furthermore, there should be an identifiable latent or early symptomatic stage, and the natural history of the condition, including development from latent to clinical disease, must be adequately understood[54]. Furthermore, there should be an agreement upon policy as to whom to treat, taking into consideration the patients’ resources. The cost of case finding (including diagnosis) should be economically balanced in relation to possible expenditures for medical care as a whole, while case finding should be a continuing process and not a "one-off" strategy. Finally, there should be an effective screening test or examination and that test should be acceptable to the population[54]. It is obvious that PCOS covers all the prerequisites described above and, therefore, in all consensus statements by several experts, screening for T2D is recommended in women with PCOS (Table 2).

After the ADA’s recommendation for a single HbA1c measurement as an accurate index for T2D diagnosis, its use has been advocated by several research groups and international guidelines (Table 2). HbA1c cannot, however, be used for the diagnosis of dysglycemia in women suffering from PCOS for a number of reasons. First, in this group of patients, periods of oligomenorrhea are followed by periods of heavy bleeding or sychnomenorrhea and this menstrual pattern could result in major changes in hematocrit and/or ferritin levels. Since HbA1c is dependent on these parameters, iron depletion and loading might lead to significant variations in HbA1c concentrations over time, independently of the patient’s glycemic status[73]. Moreover, the specificity of HbA1c in the diagnosis of dysglycemia has been questioned in overweight and obese subjects[74], who constitute the largest group in the PCOS population. Additionally, the cut-off point for HbA1c is mainly based on the established association between HbA1c and microvascular disease in patients with established T2D. However, women with PCOS are younger and healthier overall when initially diagnosed with the syndrome, while dysglycemia does not always lead to T2D in this population compared to those evaluated in the original study of HbA1C validation[75], further calling HbA1c application into question.

However, whether glycemic status should be evaluated in every woman suffering from PCOS or in certain subgroups, as well as which is the best method for this assessment, are to date unanswered questions. With regard to which patients should be screened, there are at present two points of view. One, supported by the Endocrine Society, the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society, as well as by the guidelines on PCOS diagnosis and management developed in Australia, suggests universal screening in all women with PCOS[55-57]. On the other hand, a number of experts recommend screening in women with at least one risk factor, such as age >40 years, family history of either T2D or gestational diabetes mellitus, and/or obesity[58-60]. However, the latter recommendations have not been supported by solid data, since studies arguing either in favor of or against them have been published[4,61]. For example, the family history of T2D criterion has strong supportive data in studies from the USA and Australia[62,63], but not in studies originating from Italy and Germany[9,64]. Accordingly, these criteria, although reasonable, appear ultimately to be arbitrary and would not reflect the different nature of T2D development in PCOS compared to that in the unaffected population. In a similar manner, most of the studies in favor of these recommendations did not evaluate in detail the impact of age, obesity, and hyperandrogenemia on the development of dysglycemia and, thus, seem to increase controversy over this matter[4,65].

In general, whether the increased T2D risk exists in both obese and non-obese PCOS has not as yet been fully elucidated. A recent meta-analysis by Zhu

[10] that assessed the risk of T2D in non-obese PCOS compared to non-obese control women showed an increased risk in this PCOS subpopulation, although to a lesser extent compared to obese PCOS (five studies; OR 1.47; 95%CI: 1.11-1.93). The authors additionally reported an increased prevalence of IR, IGT, and atherogenic dyslipidemia in non-obese PCOS compared to non-obese non-PCOS women. It must be underlined that the PCOS populations in the included studies were all premenopausal[10]. Of note, a prospective cohort study of this meta-analysis assessed the incidence of T2D at the age of 46 years in a cohort of 279 women with both oligoamenorrhea and hirsutism at the age 31 years, who had been defined as “PCOS”. This cohort was compared with 1577 women, without oligoamenorrhea and hirsutism, who served as controls. Women with PCOS and BMI > 25 kg/m

demonstrated a 2.5-fold increased risk of T2D compared to non-PCOS (OR 2.45; 95%CI: 1.28-4.67). It is notable that no such risk was identified in PCOS women of normal weight[127]. A very recent casecontrol study (1136 PCOS patients, aged 15 to 44 years, and 5675 controls) showed an increased risk of T2D in PCOS independently of BMI (adjusted OR in the entire cohort 2.36, 95%CI: 1.79-3.08; OR in non-obese PCOS 2.33, 95%CI: 1.71-3.18; OR in obese PCOS 2.85, 95%CI: 1.59-5.11)[128].

In addition, the ADA and WHO are in agreement regarding the glucose concentration cut-off for the diagnosis of IGT, which is not the case for either FPG or HbA1c values. Furthermore, in several studies it has been shown that a single measurement of FPG could misclassify a substantial number of patients with either IGT or T2D, ranging from 20%-40%, as having normal glucose homeostasis[21,64,71]. This figure is certainly not negligible given that women with PCOS are at risk for T2D, even from their early reproductive years, compared to their healthy peers. Other benefits of an OGTT are that it can be applied in patients with iron deficiency, a condition commonly encountered in women of reproductive age, while the parallel measurement of insulin concentrations after a glycemic load provides the clinician with an accurate estimate of the degree of existing IR[72].

14. Seven: The number seven is the number of completeness and totality - it is the sum of three (the number of the heavens - the triple goddess, the trinity) and four (the number of the earth which has four corners, four elements, four winds, four seasons, etc). Seven is a manifestatin of the cosmic order, a symbol of perfection and fullness, and also of introspection, meditation and understanding.

She appeared suddenly, in all her splendour, and cried: Stay, Grumedan; this Princess is under my protection, and the smallest impertinence will cost you a thousand years of captivity29

Besides this, HbA1c is a costly procedure, harmonization of HbA1c assays around the globe has not yet been carried out effectively, significant variation across ethnicities has been described, and international standardization is not as yet complete[76]. The diagnostic performance of HbA1c as a marker of glucose intolerance is further compromised by the discordance between the diagnostic criteria for prediabetes proposed by the WHO [42 mmol/mol (6.0%)] and those by the ADA [39 mmol/mol (5.7%)], producing much confusion. Furthermore, available studies evaluating the ability of HbA1c to detect IGT and diabetes in PCOS have found that the test has low sensitivity when compared with OGTT for the assessment of glucose tolerance[66,67]. Finally, the diagnostic accuracy of HbA1c in detecting T2D has recently been questioned, with some investigators arguing strongly in favor of OGTT for this procedure[77].

There is, moreover, much discordance among experts regarding the frequency of glycemic status assessment, ranging from yearly to on a five-year basis depending on the coexistence of additional factors. All the latter recommendations are illustrated in Table 2. However, from a pathophysiological point of view, PCOS women with IFG constitute a different subgroup from those with IGT. In fact, data derived from a healthy population have shown that isolated IFG is usually observed in subjects with predominantly hepatic IR and normal muscle insulin sensitivity, whereas individuals with isolated IGT have normal to slightly reduced hepatic insulin sensitivity and moderate to severe muscle IR[78]. Accordingly, those with IFG may represent the general population of women prone to T2D development, whereas subjects with IGT may compose that group of patients in whom dysglycemia occurs as a consequence of hyperandrogenemia. Today, in fact, copious documentation of the detrimental effects of androgens on muscle insulin sensitivity in lean women with PCOS is underway[1].

Conflicting data exist regarding the prevalence of intermediate hyperglycemia, namely, IGT and IFG. The prevalence of IGT in PCOS ranges from 4%-35.4%, with an average of 16.6%; in contrast, the corresponding prevalence in the healthy peers of women with PCOS ranges from 4%-8%[12]. The reasons for this very high heterogeneity have not been fully elucidated; however, ethnic susceptibility, the various criteria applied for PCOS diagnosis, as well as age and BMI distribution in the different studied groups could partly explain this diversity. Likewise, IFG prevalence as reported in the literature ranges from 2%-21%, the average being 10.8%, higher than that of the non-PCOS population, in which it is approximately 5.9% (range 4%-8.7%)[20]. In addition to the reasons provided above, the diagnostic criteria employed to diagnose IFG also play an important role, with IFG cut-offs differing significantly between the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the World Health Organization (WHO) clinical practice guidelines. Therefore, it is not surprising that the prevalence of IFG was higher in studies using the stricter ADA criteria[21] than in those using the corresponding WHO cut-off values[22]. The prevalence of dysglycemia as reported in different studies according to the country where the study was performed, the subjects’ age and BMI, and the diagnostic criteria to confirm the diagnosis of either PCOS or glycemia are presented in Table 1.

The conversion rate from normal glucose homeostasis to IGT or from IGT to T2D in PCOS has been estimated to range from 2.5 to 3.6% annually over a period of 3-8 years[79-81]. These conversion rates are lower than those observed in individuals with IGT in the general population, who seem to develop T2D at rates of approximately 7% annually[82]. This discrepancy may be related to the fact that the underlying mechanisms of T2D development in PCOS are different from those found in healthy individuals. In fact, in non-PCOS women, the degree of insulin sensitivity progressively deteriorates, thus leading almost inevitably to T2D. In contrast, in women with PCOS, a diversity of IR values has been observed over time, appearing to improve in lean subjects and worsen only when obesity is present[52,53]. Non-linear progression to T2D is therefore quite frequent in subjects suffering from PCOS, and this strongly correlates with their degree of adiposity. This notion is further supported by Celik

[83] who showed that obese women with PCOS had a 4-fold greater risk of converting from normal glucose tolerance to IGT. The latter finding was additionally corroborated by Rubin

[4] who demonstrated that lean women with PCOS had an equal risk of progressing to T2D to that of controls.

RISK FACTORS FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF T2D IN PCOS

Several parameters which could possibly mediate the risk of developing T2D in women with PCOS have recently been evaluated. With regard to PCOS phenotypes, the presence of the most severe form of PCOS, consisting of the conglomeration of chronic anovulation and elevated androgen concentrations (former NIH criteria), was found to be one of the strongest independent predictors of glucose concentrations after a 75-g OGTT in 254 women with PCOS following adjustment for several confounders, including age, waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), and BMI[61]. However, this finding has not since been replicated[13].

Based on the well-known developmental origins of health and disease, an inverse association between birth weight and T2D risk seems highly likely. Indeed, low birth weight has been associated with PCOS diagnosis later in life, with a birth weight < 2.5 kg conferring a 76% higher likelihood of developing PCOS[84]. In a similar manner, age of menarche has been related to dysglycemia in PCOS. Indeed, PCOS women with IGT were observed to have significantly earlier menarche age (11.9 ± 1.6 years) compared to obese women with PCOS and normal glucose tolerance (12.4 ± 1.7 years) in a cross-sectional study of 121 Italian PCOS women. However, the number of subjects with T2D was too small for any correlation to be established[3]. Of note, a single-center cohort study demonstrated that a higher number of births decreased the risk of T2D in women with PCOS, corroborating a potential prophylactic effect of parity in T2D[4]. In the same context, the impact of lactation on T2D development may be hypothesized. In fact, obesity in women with PCOS is a risk factor for impaired lactogenesis and increases the risk for reduced breastfeeding initiation and duration[85]. Furthermore, since lactation is crucial for women’s post-gestational metabolic health[86], the presence of abnormal lactational function might enhance the risk for T2D in this population, even though substantial data to support this hypothesis are to date lacking. Finally, a positive link has been proposed between family history of T2D and T2D risk in PCOS; this hypothesized association is based on a defect in the first phase of insulin secretion in PCOS women with a first degree relative suffering from T2D, in contrast to BMI-matched PCOS patients without such a history[87].

Given that PCOS is characterized by markedly higher androgen concentrations compared to those in the unaffected population, an association between the syndrome and T2D constitutes a rational hypothesis. In fact, such correlations were originally reported almost 40 years ago[35]. Ever since, multiple studies have confirmed this relationship in both lean and obese women with PCOS. A significant positive association between testosterone concentrations and IR has been described in lean women with PCOS using OGTT-derived indices[3,36] and measures of glucose disposition in hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamps[37]. Even though PCOS is mainly characterized by hyperandrogenemia of ovarian origin, a subgroup of patients exhibits adrenal androgen hypersecretion, with the most important being dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate. In the latter subgroup, hyperandrogenemia does not seem to correlate with IR indices or metabolic abnormalities in most[38-42], but not all, studies[43,44]. It is a riddle that remains as yet unresolved, especially taking into consideration that such an association does seem to exist in other conditions of adrenal hyperandrogenism, such as premature adrenarche/pubarche[45].

Three of the most common addictions have been incriminated in PCOS pathophysiology and, possibly, in the development of T2D, namely, smoking, caffeine, and alcohol. Regarding tobacco use, a cross-sectional study of 309 women with PCOS identified a significant positive correlation between lipid concentrations and years of smoking, while IR was significantly higher in smokers with PCOS compared to nonsmokers, despite the absence of a significant association between HOMA-IR and packyears among the participants[94]. In addition, HOMA-IR and fasting insulin concentrations were higher in smokers with PCOS compared with their non-smoker counterparts in a German study of 346 women with PCOS, although the latter analysis was not adjusted for BMI or age[95]. Regarding caffeine, higher intake has been associated with worse reproductive outcomes in women with PCOS, but no study to date has found any association with glucose homeostasis[96]. Finally, a positive association between alcohol consumption and PCOS has been documented[97].

Another risk factor contributing to impaired glucose homeostasis may be vitamin D deficiency. Regarding PCOS, lower 25-hydroxy-vitamin D [25(OH)D] concentrations have been reported in PCOS patients compared to those in controls, with vitamin D deficiency [25OHD < 20 ng/mL] being associated with higher fasting glucose and insulin concentrations, as well as IR, assessed by OGTT[98]. A meta-analysis combining data from 11 placebo-controlled randomized trials evaluating the effects of vitamin D supplementation on glucose homeostasis in 601 patients with PCOS (89% of Asian descent) found that daily supplementation with small doses of vitamin D was able to significantly lower HOMA-IR index (daily supplementation effect -0.30;

= 0.0018, low-dose supplementation effect ?0.31;

= 0.0016)[99]. However, both studies failed to report data regarding the relationship between vitamin D deficiency and T2D.

The big old monster greedily accepted my dime, and I heard the bottles shift. On tiptoes I reached up and opened the heavy door. There they were: one neat row of thick green bottles, necks staring directly at me, and icecold from the refrigeration. I held the door open with my shoulder and grabbed one. With a quick yank, I pulled it free from its bondage15. Another one immediately took it place. The bottle was cold in my sweaty hands. I will never forget the feeling of the cool glass on my skin. With two hands, I positioned the bottleneck16 under the heavy brass17 opener that was bolted to the wall. The cap dropped into an old wooden box, and I reached in to retrieve18 it. I was cold and bent19 in the middle, but I knew I needed to have this souvenir. Coke in hand, I proudly marched back out into the early evening dusk. Grampy was waiting patiently. He smiled.

Taking a more holistic approach, other emerging factors in T2D development are sleep quality and mood disorders. It is well-known that women with PCOS, even after controlling for obesity, tend to have a higher prevalence of sleep disturbances, such as reduced sleep efficiency, amount of time spent in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, as well as non-REM sleep, and difficulty in falling asleep and maintaining sleep[100]. Moreover, the prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea is higher in women with PCOS compared to non-PCOS [odds ratio (OR) 3.83; 95%CI: 1.43-10.24][101] and is associated with higher fasting insulin levels, HOMA-IR index, HbA1c, and glucose area under the curve[102]. On the other hand, the latter findings warrant caution, since a high likelihood for selection bias is considered plausible[101]. Depression and mood disorders have been associated with IR, obesity, and T2D in multiple studies[103]. In addition, depression and mood disorders have been commonly diagnosed in women with PCOS[104,105]. Despite the theoretical possibility of an association between these two conditions, no study has evaluated such an association to date.

In recent years, the role of the gut microbiome in metabolic abnormalities, including PCOS, has been explored[106]. It was thus inevitable that an effort would be made to improve some of the features of the syndrome by intervening in the microbial population with probiotics and synbiotics. The latter intervention was shown to confer beneficial effects on body weight, fasting plasma glucose and insulin, reproductive hormones, and hirsutism, while longer duration of treatment also seemed to be more efficacious[107].

A major factor that may eliminate or reduce T2D risk in PCOS is prescription of appropriate drugs. Oral contraceptives have been the mainstay of treatment for irregular menses, hirsutism, and acne in women with PCOS with exceptional success rates. Some studies have, however, suggested an increased risk for T2DM with this strategy[4], albeit a meta-analysis of published trials identified only a minor increase in fasting insulin concentrations[108]. By contrast, given the significance of IR in the pathophysiology of the syndrome, it comes as no surprise that metformin has been the most commonly used medication to prevent or treat the metabolic abnormalities in women with PCOS[109]. Yet, despite the high expectations, metformin combined with lifestyle changes appeared to produce only a small reduction in BMI (-0.73 kg/m

). This was, namely, a decrease in subcutaneous adipose tissue volume and an improvement in menstrual cyclicity compared to lifestyle interventions alone, these as seen in a meta-analysis of published randomized controlled trials[109]. It is, however, of note that most studies were small in sample size and the risk of bias was deemed high by the authors. Patients with concurrent diabetes were excluded in most studies, not allowing for safe conclusions to be drawn in this regard. On the other hand, metformin significantly reduced the risk for gestational diabetes (pooled OR 0.20, 95%CI: 0.12-0.1,

< 0.001), early pregnancy loss (pooled OR 0.28, 95%CI: 0.10-0.75,

= 0.01), and preterm delivery (pooled OR 0.33, 95%CI: 0.18-0.60,

= 0.0003), with significant heterogeneity between studies[110]. These outcomes did not differ between patients treated prior to pregnancy and those treated throughout the duration of their pregnancy[111].

But in that place there were some Christian25 folk59 who had been carried off, and they had been sitting in the chamber which was next to that of the Prince, and had heard how a woman had been in there who had wept and called on him two nights running, and they told the Prince of this

In addition to metformin, PPAR-γ agonists, such as rosiglitazone (not used currently due to heart failure risk) and pioglitazone, which are potent insulin sensitizers, have been studied in women with PCOS, exhibiting significant improvements in fasting blood glucose and glucose tolerance[25]. In 2017, a meta-analysis of 11 randomized controlled trials comparing the effects of metformin and pioglitazone in 643 subjects with PCOS identified a number of promising effects on reproductive and esthetic outcomes and, as expected, metformin seemed to ameliorate BMI more effectively than pioglitazone[112]. Other T2D medications have been studied in women with PCOS recently, including the SGLT-2 inhibitor empagliflozin, which produced significantly more weight loss compared to metformin in a small study of non-diabetic women[113]. Exenatide[114,115] and liraglutide[116] appeared to improve several glucose homeostasis parameters in non-diabetic women with PCOS more efficaciously than metformin, while their addition to metformin seemed to provide incremental benefits in that regard[116,117]. Finally, orlistat has been studied extensively in obese women with PCOS and was found equally efficacious to metformin in producing weight loss and metabolic improvements[118].

The blade was always bright and clear; each time she looked she had the happiness of knowing that all was well, till one evening, tired and anxious, as she frequently was at the end of the day, she took it from its drawer, and behold15! the blade was red with blood

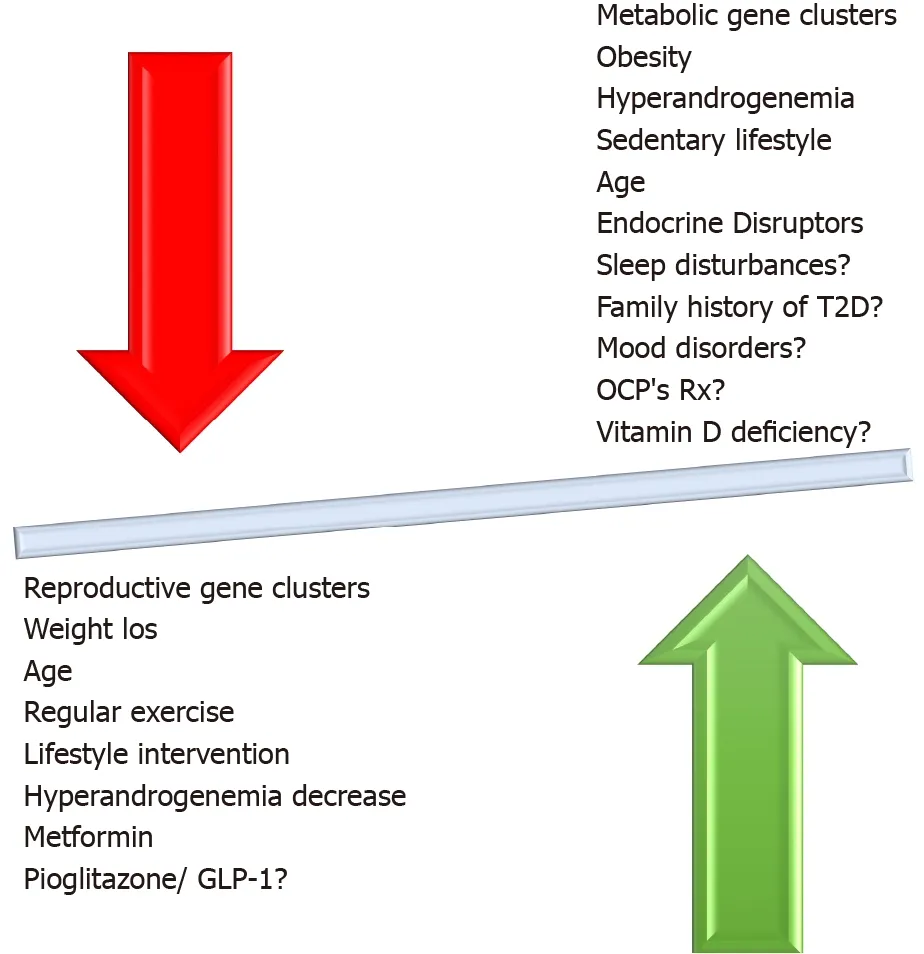

Even though supplement use has increased greatly in the past few years, supplementation with minerals, trace elements, and other supplements is, in general, still controversial. In the case of chromium supplementation in PCOS, two meta-analyses of published trials found that BMI, fasting insulin, free testosterone[119] HOMA-IR, and HOMA-β[120] seemed to improve. In addition, supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids at doses of 900-4000 mg daily appeared to improve HOMA-IR index in a meta-analysis of nine small randomized controlled trials, but no data were available on risk for T2D[121]. Myoinositol, an amino acid with potentially beneficial effects in women with PCOS, has been studied with regard to glucose metabolism, and a small positive impact on fasting insulin and HOMA-IR was found in a 2017 meta-analysis of controlled trials, without any effect on glucose concentrations or BMI[122]. The factors described above and their relationship to development of dysglycemia in PCOS are illustrated in Figure 3.

T2D IN POSTMENOPAUSAL WOMEN WITH PCOS

Based on the aforementioned data, a diagnosis of PCOS during the reproductive age places a woman at increased risk for T2D in later, post-reproductive life[123]-a risk which is further augmented if the issue of dysregulated glucose metabolism during transition to menopause is taken into account. The risk is even greater if the woman enters menopause before the age of 45[124]. A recent meta-analysis of 23 cohort studies[47] assessed the long-term cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk in women with PCOS, including T2D risk. Women with a history of PCOS demonstrated a 3-fold increased risk of T2D (RR 3.00; 95%CI: 2.56-3.51) compared to non-PCOS women. However, the studies included were quite heterogeneous in terms of the participants’ age. Very few of them included postmenopausal women, either as a single or a mixed population[8,125,126]. Another shortcoming was the heterogeneity in PCOS diagnosis among studies.

A recent prospective cohort study evaluated the risk for development of T2D in 27 PCOS women (defined by the NIH criteria) after 24 years of follow-up (mean age at baseline: 29.5 ± 5.3years; mean age at the end of follow-up: 52.4 ± 5.4 years) in comparison with age-matched non-PCOS controls (

= 94). The incidence of T2D in the former group was 19% compared to 1% in the latter (

< 0.01)[8]. Interestingly, the development of T2D was independent of lifestyle factors. Although all PCOS women with T2D were obese and had a higher BMI and WHR than non-PCOS individuals, the increases in BMI and WHR per year were comparable between groups during followup. However, an older prospective study including 35 postmenopausal women with PCOS (mean age 70.4 ± 5 years, range 61-79), diagnosed with the Rotterdam criteria, did not find any difference in T2D incidence compared to age-matched controls after 21 years of follow-up[125]. Moreover, a retrospective cohort study published in 2000, which included 319 PCOS women (mean age 56.7 years, range 38-98; 81% postmenopausal; PCOS diagnosis based on medical records) and 1060 age-matched controls, showed a 3-fold increased risk of T2D in the PCOS group (OR 2.8; 95%CI: 1.5-5.5) after a mean follow-up time of 31 years (range 15-47). However, this risk was not significant after adjustment for BMI (OR 2.2; 95%CI: 0.9-5.2)[126].

There is disagreement among experts as to whether fasting plasma glucose (FPG), OGTT, or glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) is the best laboratory method to assess glycemic status in a patient with PCOS, despite robust data strongly pointing to OGTT as being the most accurate[66,67]. The main arguments against OGTT use are that the modality is more complex, expensive, and time-consuming than the other two screening methods. Moreover, it is characterized by high variability and its results are dependent on height[68]. However, OGTT is considered the gold standard for T2D diagnosis because it constitutes a standardized test that is easily performed and is the only method able to detect IGT, of utmost importance for women with PCOS[69]. Indeed, given that the risk of T2D development in women with IGT is considerably higher than in those with normal glucose tolerance or those with IFG[9], this at-risk population can greatly benefit from early lifestyle modification and/or pharmacological intervention[70].

Oh! Daddy, not my pearls! Jenny said. But you can have Rosy4, my favorite doll. Remember her? You gave her to me last year for my birthday. And you can have her tea party outfit5, too. Okay?

Aside from BMI, other factors also play an important role in the incidence of T2D in postmenopausal women with a history of PCOS. The increased ovarian androgen production and IGT observed in premenopausal women with PCOS cases seem to persist after menopause transition. On the other hand, IR and hyperinsulinemia may improve in women with PCOS during their post-reproductive years, although data are still inconsistent as to this hypothesis[129]. Furthermore, the severity of IR is also dependent on the PCOS phenotype, since hyperandrogenemia is related to a more severe metabolic dysfunction[65].

Therefore, although transition to menopause is associated with dysregulation of glucose metabolism[130], current evidence is at present too weak to support the existence of increased T2D risk in postmenopausal women with a history of PCOS compared to those without. There are currently too many confounding factors and variables, such as PCOS definition, sample size, and the precise effect of BMI and aging, to accurately determine the actual impact, if any, of a PCOS diagnosis on T2DM risk after transition to menopause.

MANAGEMENT OF T2DM RISK IN PCOS

Lifestyle intervention, including diet modification and regular exercise, still remain the mainstay of treatment in reducing T2D risk in women with PCOS, especially those who are obese or overweight. According to a recent meta-analysis of 19 randomized controlled trials (RCTs), systematic dietary intervention is superior to advice, usual diets, or no treatment with regard to HOMA-IR [mean difference (MD) -0.78, 95%CI: -0.92 to -0.65], fasting plasma insulin (FPI) (MD -4.24 mIU/L, 95%CI: -5.37 to -3.10), FPG (MD -0.11 mmol/L, 95%CI: -0.17 to -0.04 mmol/L), as well as BMI (MD -1.01 kg/m

, 95%CI: -1.38 to -0.64) and waist circumference (WC) (MD -3.25 cm, 95%CI: -5.29 to -1.22)[131]. Subgroup analysis showed that the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet is more effective in HOMA-IR and FPG reduction than a low-carbohydrate diet (LCD), but with comparable efficacy regarding FPI concentrations. With respect to BMI and body weight, a calorie-restricted diet is more beneficial than either DASH or LCD. All dietary patterns seem to have comparable efficacy regarding WC[131]. Moreover, data from RCTs in PCOS women have shown that LCD is quite effective in reducing BMI [standardized MD (SMD) -1.04, 95%CI: -1.38 to -0.70) and HOMA-IR (SMD -0.66, 95%CI: -1.01 to -0.30) compared to a regular diet according to a recent meta-analysis[132]. In addition, a low glycemic index diet could also be the first-line approach in PCOS patients, since it effectively reduces HOMA-IR (-0.78, 95%CI: -1.20 to -0.37), WC (-2.81 cm, 95%CI: -4.40 to -1.23), and total testosterone concentrations (-0.21 nmol/L, 95%CI: -0.32 to -0.09) compared to a high glycemic index diet[133]. Although the evidence in PCOS populations is limited, the Mediterranean diet (MedDiet) compared to the typical Western diet is also effective in reducing HOMA-IR (MD -0.42, 95%CI: ?0.70 to ?0.15), FPG (MD -2.98 mg/dL, 95%CI: -4.54 to -1.42), and FPI (-0.94, 95%CI: -1.72 to -0.16) compared to a usual diet. The MedDiet is also associated with a lower tendency to develop T2DM (RR 0.81; 95%CI: 0.61-1.02) and a reduction in CVD events related to metabolic syndrome[133].

The beneficial effects of structured exercise programs in metabolic syndrome, obesity, T2D, and CVD prevention and treatment are well-known[134]. Interventions consisting of lifestyle modifications in women with PCOS produce substantial improvements in glucose homeostasis and reproductive outcomes as well. These benefits are equally significant as those achieved by metformin[135]. A negative energy balance of approximately 30%, aiming to achieve an energy deficit of 500-750 kcal per day, is able to produce significant amounts of weight loss in women with PCOS. The addition of any amount of exercise, whether aerobic or anaerobic, confers additional beneficial effects on glucose homeostasis[25]. High-intensity interval training (achieving 90%-95% of the individual’s maximum heart rate) three times a week for ≥ 10 wk is effective in reducing HOMA-IR (MD -0.57, 95%CI: -0.98 to -0.16) and BMI (MD -1.90, 95%CI: -3.37 to -0.42) in women with PCOS, according to a recent meta-analysis[136]. In cases with morbid obesity, such as those with BMI > 40 kg/m

or BMI > 35 kg/m

with metabolic comorbidities, bariatric surgery should be considered[1]. Indeed, bariatric surgery can reduce the risk of T2D by 91% (RR 0.09, 95%CI: 0.03-0.32). The mean reduction in BMI is -14.51 kg/m

(95%CI: -17.88 to -11.14). It also ameliorates menstrual disturbances and hirsutism in PCOS patients [RR 0.23 (95%CI: 0.13-0.43) and 0.47 (95%CI: 0.28-0.79), respectively][137].

Metformin is the most commonly used insulin sensitizer in women with PCOS, especially in those who are obese or overweight. According to the aforementioned meta-analysis, diet is superior to metformin with regard to weight loss, but comparably efficacious in improving glucose homeostasis (HOMA-IR, FPG, and FPI)[131]. In a recent meta-analysis of 12 RCTs, metformin was superior to placebo in reducing BMI [weighted MD (WMD) -1.25, 95%CI: -1.60 to -0.91] and WC (WMD -1.41, 95%CI: -2.46 to -0.37). There were no differences between groups with regard to HOMA-IR, FPG, and FPI[138].

For women who are intolerant to metformin, thiazolidinediones (TZDs) constitute another class of insulin sensitizers that have been evaluated in women with PCOS. Rosiglitazone and pioglitazone, the two commonly used TZDs, are effective in improving IR and IGT, as well as mensural cyclicity, in PCOS patients. However, weight gain, increase in transaminase levels, and potential teratogenic effects limit their use in these patients[1]. Compared to metformin, pioglitazone is superior with respect to menstrual cycle improvement and ovulation but inferior regarding hirsutism score. Both agents are equally effective in reducing HOMA-IR, FPG, and FPI, as mentioned above[112].

Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists (GLP-1-RAs) have also been tested in women with PCOS. A recent meta-analysis of eight RCTs (four with exenatide 10 μg twice a day; four with liraglutide 1.2 mg/d), compared their efficacy with that of metformin in women with PCOS. The study showed that GLP-1-RAs were more effective in improving HOMA-IR (SMD -0.40, 95%CI: -0.74 to -0.06) and reducing BMI (SMD -1.02, 95%CI: -1.85 to -0.19) and WC (SMD -0.45, 95%CI: -0.89 to -0.00). No difference between GLP-1-RAs and metformin in FPG and FPI was observed either between exenatide and liraglutide[139].

With that, the man darted7 across the floor and out the door, leaving the lady in much bewilderment. He finally realized that he had already found his dream girl, and she was... the Vancouver girl all along! The drunken lady had said something that awoken him.

Finally, in cases of post-menopausal women younger than 60 years and/or within 10 years since their last menstrual period who present with severe vasomotor symptomatology, especially those with early menopause (< 45 years of age), menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) may be of benefit, since it reduces T2D by up to 30%[140]. MHT exerts a beneficial effect on glucose homeostasis in women both with and without T2D. In cases with T2D and low CVD risk, oral estrogens may be considered[141]. In obese women with T2D or with moderate CVD risk, transdermal 17β-estradiol is the preferred treatment, along with a progestogen with minimal effects on glucose metabolism, such as progesterone, dydrogesterone, or transdermal norethisterone. However, this favorable effect on glucose homeostasis is dissipated after MHT discontinuation. In any case, MHT is not recommended for the sole purpose of T2D prevention or treatment[140,141].

The robber-girl looked earnestly at her, nodded her head slightly, and said, “They sha’nt kill you, even if I do get angry with you; for I will do it myself.” And then she wiped Gerda’s eyes, and stuck her own hands in the beautiful muff which was so soft and warm.

It is thus clear that weight loss, preferably with LCD and a low glycemic index diet low in AGES, combined with vigorous exercise should be the first-line lifestyle intervention in overweight or obese PCOS patients due to their well-documented beneficial effects on glucose metabolism, although longitudinal data on T2D risk are thus far lacking. The MedDiet may be even more beneficial than a low glycemic index diet in CVD risk reduction, although the current evidence in PCOS patients is weak. Metformin may also be considered in cases of impaired glucose metabolism and oligo/amenorrhea. The choice of either BS, pioglitazone, or GLP-1-RA should be individualized and benefits should be weighed against costs.

CONCLUSION

The association of PCOS with increased T2D risk is relatively robust and thus should not be neglected in any woman with the syndrome. Despite the current heterogeneity of the data, the ever-changing nature of this disorder, and the uncertainty regarding the exact mechanisms regulating progression of dysglycemia in PCOS, there are several general principles that the clinician should implement in everyday practice. First, diagnosis and follow-up of dysglycemia should preferably be based on OGTT and not on FPG or HbA1c values. Second, the non-linear development of T2D in PCOS in non-obese women highlights the importance of maintaining an optimal weight in all women suffering from the syndrome. Third, menopausal women with a history of PCOS should be regularly evaluated since they may be at higher T2D risk, especially if they are obese. Fourth, a well-balanced diet coupled with regular exercise constitutes the most appropriate approach in every patient with PCOS. Metformin administration might ameliorate the biochemical and hormonal profile in PCOS and may be considered in patients in whom prior measures have failed to improve metabolic and ovulatory dysfunction. The use of pioglitazone, GLP-1-Ras, and/or MHT may be of value in selected cases.

1 Conway G, Dewailly D, Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Escobar-Morreale HF, Franks S, Gambineri A, Kelestimur F, Macut D, Micic D, Pasquali R, Pfeifer M, Pignatelli D, Pugeat M, Yildiz BO; ESE PCOS Special Interest Group. The polycystic ovary syndrome: a position statement from the European Society of Endocrinology.

2014; 171: P1-29 [PMID: 24849517 DOI: 10.1530/EJE-14-0253]

2 Azziz R, Carmina E, Chen Z, Dunaif A, Laven JS, Legro RS, Lizneva D, Natterson-Horowtiz B, Teede HJ, Yildiz BO. Polycystic ovary syndrome.

2016; 2: 16057 [PMID: 27510637 DOI: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.57]

3 Gambineri A, Pelusi C, Manicardi E, Vicennati V, Cacciari M, Morselli-Labate AM, Pagotto U, Pasquali R. Glucose intolerance in a large cohort of mediterranean women with polycystic ovary syndrome: phenotype and associated factors.

2004; 53: 2353-2358 [PMID: 15331545 DOI: 10.2337/diabetes.53.9.2353]

4 Rubin KH, Glintborg D, Nybo M, Abrahamsen B, Andersen M. Development and Risk Factors of Type 2 Diabetes in a Nationwide Population of Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.

2017; 102: 3848-3857 [PMID: 28938447 DOI: 10.1210/jc.2017-01354]

5 Cassar S, Misso ML, Hopkins WG, Shaw CS, Teede HJ, Stepto NK. Insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of euglycaemic-hyperinsulinaemic clamp studies.

2016; 31: 2619-2631 [PMID: 27907900 DOI: 10.1093/humrep/dew243]

6 Dunaif A, Finegood DT. Beta-cell dysfunction independent of obesity and glucose intolerance in the polycystic ovary syndrome.

1996; 81: 942-947 [PMID: 8772555 DOI: 10.1210/jcem.81.3.8772555]

7 Barber TM, Franks S. Obesity and polycystic ovary syndrome.

2021; 95: 531-541 [PMID: 33460482 DOI: 10.1111/cen.14421]

8 Forslund M, Landin-Wilhelmsen K, Trimpou P, Schmidt J, Br?nnstr?m M, Dahlgren E. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in women with polycystic ovary syndrome during a 24-year period: importance of obesity and abdominal fat distribution.

2020; 2020: hoz042 [PMID: 31976382 DOI: 10.1093/hropen/hoz042]

9 Gambineri A, Patton L, Altieri P, Pagotto U, Pizzi C, Manzoli L, Pasquali R. Polycystic ovary syndrome is a risk factor for type 2 diabetes: results from a long-term prospective study.

2012; 61: 2369-2374 [PMID: 22698921 DOI: 10.2337/db11-1360]

10 Zhu T, Cui J, Goodarzi MO. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes, Coronary Heart Disease, and Stroke.

2021; 70: 627-637 [PMID: 33158931 DOI: 10.2337/db20-0800]

11 Dapas M, Lin FTJ, Nadkarni GN, Sisk R, Legro RS, Urbanek M, Hayes MG, Dunaif A. Distinct subtypes of polycystic ovary syndrome with novel genetic associations: An unsupervised, phenotypic clustering analysis.

2020; 17: e1003132 [PMID: 32574161 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003132]

12 Huebschmann AG, Huxley RR, Kohrt WM, Zeitler P, Regensteiner JG, Reusch JEB. Sex differences in the burden of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular risk across the life course.

2019; 62: 1761-1772 [PMID: 31451872 DOI: 10.1007/s00125-019-4939-5]

13 Pelanis R, Mellembakken JR, Sundstr?m-Poromaa I, Ravn P, Morin-Papunen L, Tapanainen JS, Piltonen T, Puurunen J, Hirschberg AL, Fedorcsak P, Andersen M, Glintborg D. The prevalence of Type 2 diabetes is not increased in normal-weight women with PCOS.

2017; 32: 2279-2286 [PMID: 29040530 DOI: 10.1093/humrep/dex294]

14 Ganie MA, Dhingra A, Nisar S, Sreenivas V, Shah ZA, Rashid A, Masoodi S, Gupta N. Oral glucose tolerance test significantly impacts the prevalence of abnormal glucose tolerance among Indian women with polycystic ovary syndrome: lessons from a large database of two tertiary care centers on the Indian subcontinent.

2016; 105: 194-201.e1 [PMID: 26407537 DOI: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.09.005]

15 Seneviratne HR, Lankeshwara D, Wijeratne S, Somasunderam N, Athukorale D. Serum insulin patterns and the relationship between insulin sensitivity and glycaemic profile in women with polycystic ovary syndrome.

2009; 116: 1722-1728 [PMID: 19775306 DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02360.x]

16 Nanditha A, Ma RC, Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Chan JC, Chia KS, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ. Diabetes in Asia and the Pacific: Implications for the Global Epidemic.

2016; 39: 472-485 [PMID: 26908931 DOI: 10.2337/dc15-1536]

17 Kakoly NS, Khomami MB, Joham AE, Cooray SD, Misso ML, Norman RJ, Harrison CL, Ranasinha S, Teede HJ, Moran LJ. Ethnicity, obesity and the prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes in PCOS: a systematic review and meta-regression.

2018; 24: 455-467 [PMID: 29590375 DOI: 10.1093/humupd/dmy007]

18 Lizneva D, Kirubakaran R, Mykhalchenko K, Suturina L, Chernukha G, Diamond MP, Azziz R. Phenotypes and body mass in women with polycystic ovary syndrome identified in referral

unselected populations: systematic review and meta-analysis.

2016; 106: 1510-1520.e2 [PMID: 27530062 DOI: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.07.1121]

19 Zhang B, Wang J, Shen S, Liu J, Sun J, Gu T, Ye X, Zhu D, Bi Y. Association of Androgen Excess with Glucose Intolerance in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.

2018; 2018: 6869705 [PMID: 29707577 DOI: 10.1155/2018/6869705]

20 Eades CE, France EF, Evans JM. Prevalence of impaired glucose regulation in Europe: a metaanalysis.

2016; 26: 699-706 [PMID: 27423001 DOI: 10.1093/eurpub/ckw085]

21 Veltman-Verhulst SM, Goverde AJ, van Haeften TW, Fauser BC. Fasting glucose measurement as a potential first step screening for glucose metabolism abnormalities in women with anovulatory polycystic ovary syndrome.

2013; 28: 2228-2234 [PMID: 23739218 DOI: 10.1093/humrep/det226]

22 Amato MC, Magistro A, Gambino G, Vesco R, Giordano C. Visceral adiposity index and DHEAS are useful markers of diabetes risk in women with polycystic ovary syndrome.

2015; 172: 79-88 [PMID: 25342852 DOI: 10.1530/EJE-14-0600]

23 Teede HJ, Misso ML, Costello MF, Dokras A, Laven J, Moran L, Piltonen T, Norman RJ; International PCOS Network. Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome.

2018; 33: 1602-1618 [PMID: 30052961 DOI: 10.1093/humrep/dey256]

24 Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Dunaif A. Insulin resistance and the polycystic ovary syndrome revisited: an update on mechanisms and implications.

2012; 33: 981-1030 [PMID: 23065822 DOI: 10.1210/er.2011-1034]

25 Pani A, Gironi I, Di Vieste G, Mion E, Bertuzzi F, Pintaudi B. From Prediabetes to Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Lifestyle and Pharmacological Management.

2020; 2020: 6276187 [PMID: 32587614 DOI: 10.1155/2020/6276187]

26 Burghen GA, Givens JR, Kitabchi AE. Correlation of hyperandrogenism with hyperinsulinism in polycystic ovarian disease.

1980; 50: 113-116 [PMID: 7350174 DOI: 10.1210/jcem-50-1-113]

27 Chang RJ, Nakamura RM, Judd HL, Kaplan SA. Insulin resistance in nonobese patients with polycystic ovarian disease.

1983; 57: 356-359 [PMID: 6223044 DOI: 10 .1210/jcem-57-2-356]

28 Dunaif A, Graf M, Mandeli J, Laumas V, Dobrjansky A. Characterization of groups of hyperandrogenic women with acanthosis nigricans, impaired glucose tolerance, and/or hyperinsulinemia.

1987; 65: 499-507 [PMID: 3305551 DOI: 10.1210/jcem-65-3-499]

29 Dong Z, Huang J, Huang L, Chen X, Yin Q, Yang D. Associations of acanthosis nigricans with metabolic abnormalities in polycystic ovary syndrome women with normal body mass index.

2013; 40: 188-192 [PMID: 23289590 DOI: 10.1111/1346-8138.12052]

30 Morciano A, Romani F, Sagnella F, Scarinci E, Palla C, Moro F, Tropea A, Policola C, Della Casa S, Guido M, Lanzone A, Apa R. Assessment of insulin resistance in lean women with polycystic ovary syndrome.

2014; 102: 250-256.e3 [PMID: 24825420 DOI: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.04.004]

31 Vrbíková J, Cibula D, Dvoráková K, Stanická S, Sindelka G, Hill M, Fanta M, Vondra K, Skrha J. Insulin sensitivity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome.

2004; 89: 2942-2945 [PMID: 15181081 DOI: 10.1210/jc.2003-031378]

32 Ding EL, Song Y, Malik VS, Liu S. Sex differences of endogenous sex hormones and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

2006; 295: 1288-1299 [PMID: 16537739 DOI: 10.1001/jama.295.11.1288]

33 Oh JY, Barrett-Connor E, Wedick NM, Wingard DL; Rancho Bernardo Study. Endogenous sex hormones and the development of type 2 diabetes in older men and women: the Rancho Bernardo study.

2002; 25: 55-60 [PMID: 11772901 DOI: 10.2337/diacare.25.1.55]

34 Muka T, Nano J, Jaspers L, Meun C, Bramer WM, Hofman A, Dehghan A, Kavousi M, Laven JS, Franco OH. Associations of Steroid Sex Hormones and Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin With the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes in Women: A Population-Based Cohort Study and Meta-analysis.

2017; 66: 577-586 [PMID: 28223343 DOI: 10.2337/db16-0473]

35 Cotrozzi G, Matteini M, Relli P, Lazzari T. Hyperinsulinism and insulin resistance in polycystic ovarian syndrome: a verification using oral glucose, I.V. Glucose and tolbutamide.

1983; 20: 135-142 [PMID: 6224386 DOI: 10.1007/BF02624914]

36 Takeuchi T, Tsutsumi O, Taketani Y. Abnormal response of insulin to glucose loading and assessment of insulin resistance in non-obese patients with polycystic ovary syndrome.

2008; 24: 385-391 [PMID: 18645711 DOI: 10.1080/09513590802173584]

37 Toprak S, Y?nem A, Cakir B, Güler S, Azal O, Ozata M, Corak?i A. Insulin resistance in nonobese patients with polycystic ovary syndrome.

2001; 55: 65-70 [PMID: 11509861 DOI: 10.1159/000049972]

38 Lerchbaum E, Schwetz V, Giuliani A, Pieber TR, Obermayer-Pietsch B. Opposing effects of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate and free testosterone on metabolic phenotype in women with polycystic ovary syndrome.

2012; 98: 1318-25.e1 [PMID: 22835450 DOI: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.07.1057]

39 Moran C, Arriaga M, Arechavaleta-Velasco F, Moran S. Adrenal androgen excess and body mass index in polycystic ovary syndrome.

2015; 100: 942-950 [PMID: 25514100 DOI: 10.1210/jc.2014-2569]

40 Paschou SA, Palioura E, Ioannidis D, Anagnostis P, Panagiotakou A, Loi V, Karageorgos G, Goulis DG, Vryonidou A. Adrenal hyperandrogenism does not deteriorate insulin resistance and lipid profile in women with PCOS.

2017; 6: 601-606 [PMID: 28912337 DOI: 10.1530/EC-17-0239]

41 Patlolla S, Vaikkakara S, Sachan A, Venkatanarasu A, Bachimanchi B, Bitla A, Settipalli S, Pathiputturu S, Sugali RN, Chiri S. Heterogenous origins of hyperandrogenism in the polycystic ovary syndrome in relation to body mass index and insulin resistance.

2018; 34: 238-242 [PMID: 29068242 DOI: 10.1080/09513590.2017.1393062]

42 Rittmaster RS, Deshwal N, Lehman L. The role of adrenal hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, and obesity in the pathogenesis of polycystic ovarian syndrome.

1993; 76: 1295-1300 [PMID: 8388405 DOI: 10.1210/jcem.76.5.8388405]

43 Alpa?és M, Luque-Ramírez M, Martínez-García Má, Fernández-Durán E, álvarez-Blasco F, Escobar-Morreale HF. Influence of adrenal hyperandrogenism on the clinical and metabolic phenotype of women with polycystic ovary syndrome.

2015; 103: 795-801.e2 [PMID: 25585504 DOI: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.12.105]

44 Brennan K, Huang A, Azziz R. Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate and insulin resistance in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome.

2009; 91: 1848-1852 [PMID: 18439591 DOI: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.101]

45 Livadas S, Bothou C, Kanaka-Gantenbein C, Chiotis D, Angelopoulos N, Macut D, Chrousos GP. Unfavorable Hormonal and Psychologic Profile in Adult Women with a History of Premature Adrenarche and Pubarche, Compared to Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.

2020; 52: 179-185 [PMID: 32074632 DOI: 10.1055/a-1109-2630]

46 Hansen SL, Svendsen PF, Jeppesen JF, Hoeg LD, Andersen NR, Kristensen JM, Nilas L, Lundsgaard AM, Wojtaszewski JFP, Madsbad S, Kiens B. Molecular Mechanisms in Skeletal Muscle Underlying Insulin Resistance in Women Who Are Lean With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.

2019; 104: 1841-1854 [PMID: 30544235 DOI: 10.1210/jc.2018-01771]

47 Wekker V, van Dammen L, Koning A, Heida KY, Painter RC, Limpens J, Laven JSE, Roeters van Lennep JE, Roseboom TJ, Hoek A. Long-term cardiometabolic disease risk in women with PCOS: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

2020; 26: 942-960 [PMID: 32995872 DOI: 10.1093/humupd/dmaa029]

48 Anagnostis P, Paparodis R, Bosdou J, Bothou C, Goulis DG, Macut D, Dunaif A, Livadas S. The major impact of obesity on the development of type 2 diabetes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies.

2021; 3 [DOI: 10.1210/js.2019-MON-547]

49 Elting MW, Korsen TJ, Bezemer PD, Schoemaker J. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus, hypertension and cardiac complaints in a follow-up study of a Dutch PCOS population.

2001; 16: 556-560 [PMID: 11228228 DOI: 10.1093/humrep/16.3.556]

50 Lee H, Oh JY, Sung YA, Chung H, Cho WY. The prevalence and risk factors for glucose intolerance in young Korean women with polycystic ovary syndrome.

2009; 36: 326-332 [PMID: 19688613 DOI: 10.1007/s12020-009-9226-7]

51 Wei HJ, Young R, Kuo IL, Liaw CM, Chiang HS, Yeh CY. Prevalence of insulin resistance and determination of risk factors for glucose intolerance in polycystic ovary syndrome: a cross-sectional study of Chinese infertility patients.

2009; 91: 1864-1868 [PMID: 18565519 DOI: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.168]

52 Livadas S, Kollias A, Panidis D, Diamanti-Kandarakis E. Diverse impacts of aging on insulin resistance in lean and obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome: evidence from 1345 women with the syndrome.

2014; 171: 301-309 [PMID: 25053727 DOI: 10.1530/EJE-13-1007]

53 Livadas S, Macut D, Bothou C, Kuliczkowska-P?aksej J, Vryonidou A, Bjekic-Macut J, Mouslech Z, Milewicz A, Panidis D. Insulin resistance, androgens, and lipids are gradually improved in an age-dependent manner in lean women with polycystic ovary syndrome: insights from a large Caucasian cohort.

2020; 19: 531-539 [PMID: 32451980 DOI: 10.1007/s42000-020-00211-z]

54 Wilson JMG, Jungner G; Organization WH. Principles and practice of screening for disease. World Health Organization, 1968

55 Legro RS, Arslanian SA, Ehrmann DA, Hoeger KM, Murad MH, Pasquali R, Welt CK; Endocrine Society. Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline.

2013; 98: 4565-4592 [PMID: 24151290 DOI: 10.1210/jc.2013-2350]

56 Goodman NF, Cobin RH, Futterweit W, Glueck JS, Legro RS, Carmina E; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE); American College of Endocrinology (ACE); Androgen Excess and PCOS Society. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology, and Androgen Excess and PCOS Society Disease State Clinical Review: Guide to the Best Practices in the Evaluation and Treatment of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome - Part 2.

2015; 21: 1415-1426 [PMID: 26642102 DOI: 10.4158/EP15748.DSCPT2]

57 Jean Hailes for women’s health on behalf of the PCOS Australian alliance. Evidence-based guidelines for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Melbourne: Jean Hailes Foundation for Women’s Health on behalf of the PCOS Australian Alliance, 2015: 64-65

58 Wild RA, Carmina E, Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Dokras A, Escobar-Morreale HF, Futterweit W, Lobo R, Norman RJ, Talbott E, Dumesic DA. Assessment of cardiovascular risk and prevention of cardiovascular disease in women with the polycystic ovary syndrome: a consensus statement by the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (AE-PCOS) Society.

2010; 95: 2038-2049 [PMID: 20375205 DOI: 10.1210/jc.2009-2724]

59 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome, Long-term Consequences (Green-top Guideline No. 33). Available from: https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/guidelines/gtg33/

60 Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome.

2004; 81: 19-25 [PMID: 14711538 DOI: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.004]

61 Legro RS, Kunselman AR, Dodson WC, Dunaif A. Prevalence and predictors of risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in polycystic ovary syndrome: a prospective, controlled study in 254 affected women.

1999; 84: 165-169 [PMID: 9920077 DOI: 10.1210/jcem.84.1.5393]

62 Ehrmann DA, Barnes RB, Rosenfield RL, Cavaghan MK, Imperial J. Prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome.

1999; 22: 141-146 [PMID: 10333916 DOI: 10.2337/diacare.22.1.141]

63 Dabadghao P, Roberts BJ, Wang J, Davies MJ, Norman RJ. Glucose tolerance abnormalities in Australian women with polycystic ovary syndrome.

2007; 187: 328-331 [PMID: 17874978 DOI: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01273.x]

64 M?hlig M, Fl?ter A, Spranger J, Weickert MO, Schill T, Schl?sser HW, Brabant G, Pfeiffer AF, Selbig J, Sch?fl C. Predicting impaired glucose metabolism in women with polycystic ovary syndrome by decision tree modelling.

2006; 49: 2572-2579 [PMID: 16972044 DOI: 10.1007/s00125-006-0395-0]

65 Carmina E, Campagna AM, Lobo RA. A 20-year follow-up of young women with polycystic ovary syndrome.

2012; 119: 263-269 [PMID: 22270277 DOI: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823f7135]

66 Celik C, Abali R, Bastu E, Tasdemir N, Tasdemir UG, Gul A. Assessment of impaired glucose tolerance prevalence with hemoglobin A?c and oral glucose tolerance test in 252 Turkish women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a prospective, controlled study.

2013; 28: 1062-1068 [PMID: 23335611 DOI: 10.1093/humrep/det002]

67 Velling Magnussen L, Mumm H, Andersen M, Glintborg D. Hemoglobin A1c as a tool for the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes in 208 premenopausal women with polycystic ovary syndrome.

2011; 96: 1275-1280 [PMID: 21982282 DOI: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.08.035]

68 Sicree RA, Zimmet PZ, Dunstan DW, Cameron AJ, Welborn TA, Shaw JE. Differences in height explain gender differences in the response to the oral glucose tolerance test- the AusDiab study.

2008; 25: 296-302 [PMID: 18307457 DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02362.x]

69 Andersen M, Glintborg D. Diagnosis and follow-up of type 2 diabetes in women with PCOS: a role for OGTT?

2018; 179: D1-D14 [PMID: 29921567 DOI: 10.1530/EJE-18-0237]

70 Gillies CL, Abrams KR, Lambert PC, Cooper NJ, Sutton AJ, Hsu RT, Khunti K. Pharmacological and lifestyle interventions to prevent or delay type 2 diabetes in people with impaired glucose tolerance: systematic review and meta-analysis.

2007; 334: 299 [PMID: 17237299 DOI: 10.1136/bmj.39063.689375.55]

71 Vrbikova J, Hill M, Fanta M. The utility of fasting plasma glucose to identify impaired glucose metabolism in women with polycystic ovary syndrome.

2014; 30: 664-666 [PMID: 24734869 DOI: 10.3109/09513590.2014.912265]

72 Lorenzo C, Haffner SM, Stan?áková A, Kuusisto J, Laakso M. Fasting and OGTT-derived measures of insulin resistance as compared with the euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp in nondiabetic Finnish offspring of type 2 diabetic individuals.

2015; 100: 544-550 [PMID: 25387258 DOI: 10.1210/jc.2014-2299]

73 Solomon A, Hussein M, Negash M, Ahmed A, Bekele F, Kahase D. Effect of iron deficiency anemia on HbA1c in diabetic patients at Tikur Anbessa specialized teaching hospital, Addis Ababa Ethiopia.

2019; 19: 2 [PMID: 30647919 DOI: 10.1186/s12878-018-0132-1]

74 Chatzianagnostou K, Vigna L, Di Piazza S, Tirelli AS, Napolitano F, Tomaino L, Bamonti F, Traghella I, Vassalle C. Low concordance between HbA1c and OGTT to diagnose prediabetes and diabetes in overweight or obesity.

2019; 91: 411-416 [PMID: 31152677 DOI: 10.1111/cen.14043]

75 The relationship of glycemic exposure (HbA1c) to the risk of development and progression of retinopathy in the diabetes control and complications trial.

1995; 44: 968-983 [PMID: 7622004]

76 Cavagnolli G, Pimentel AL, Freitas PA, Gross JL, Camargo JL. Effect of ethnicity on HbA1c levels in individuals without diabetes: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

2017; 12: e0171315 [PMID: 28192447 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171315]

77 Bergman M, Abdul-Ghani M, Neves JS, Monteiro MP, Medina JL, Dorcely B, Buysschaert M. Pitfalls of HbA1c in the Diagnosis of Diabetes.

2020; 105 [PMID: 32525987 DOI: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa372]

78 Abdul-Ghani MA, Tripathy D, DeFronzo RA. Contributions of beta-cell dysfunction and insulin resistance to the pathogenesis of impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glucose.

2006; 29: 1130-1139 [PMID: 16644654 DOI: 10.2337/dc05-2179]

79 Norman RJ, Masters L, Milner CR, Wang JX, Davies MJ. Relative risk of conversion from normoglycaemia to impaired glucose tolerance or non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus in polycystic ovarian syndrome.

2001; 16: 1995-1998 [PMID: 11527911 DOI: 10.1093/humrep/16.9.1995]

80 Pesant MH, Baillargeon JP. Clinically useful predictors of conversion to abnormal glucose tolerance in women with polycystic ovary syndrome.

2011; 95: 210-215 [PMID: 20655529 DOI: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.06.036]

81 Boudreaux MY, Talbott EO, Kip KE, Brooks MM, Witchel SF. Risk of T2DM and impaired fasting glucose among PCOS subjects: results of an 8-year follow-up.

2006; 6: 77-83 [PMID: 16522285 DOI: 10.1007/s11892-006-0056-1]

82 Tuomilehto J, Lindstr?m J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, H?m?l?inen H, Ilanne-Parikka P, Kein?nen-Kiukaanniemi S, Laakso M, Louheranta A, Rastas M, Salminen V, Uusitupa M; Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance.

2001; 344: 1343-1350 [PMID: 11333990 DOI: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801]

83 Celik C, Tasdemir N, Abali R, Bastu E, Yilmaz M. Progression to impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes mellitus in polycystic ovary syndrome: a controlled follow-up study.

2014; 101: 1123-8.e1 [PMID: 24502891 DOI: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.12.050]

84 Sadrzadeh S, Hui EVH, Schoonmade LJ, Painter RC, Lambalk CB. Birthweight and PCOS: systematic review and meta-analysis.

2017; 2017: hox010 [PMID: 30895228 DOI: 10.1093/hropen/hox010]

85 Harrison CL, Teede HJ, Joham AE, Moran LJ. Breastfeeding and obesity in PCOS.

2016; 11: 449-454 [PMID: 30058915 DOI: 10.1080/17446651.2016.1239523]

86 Gouveri E, Papanas N, Hatzitolios AI, Maltezos E. Breastfeeding and diabetes.

2011; 7: 135-142 [PMID: 21348815 DOI: 10.2174/157339911794940684]

87 Ehrmann DA, Sturis J, Byrne MM, Karrison T, Rosenfield RL, Polonsky KS. Insulin secretory defects in polycystic ovary syndrome. Relationship to insulin sensitivity and family history of noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus.

1995; 96: 520-527 [PMID: 7615824 DOI: 10 .1172/JCI118064]

88 Hu Y, Wen S, Yuan D, Peng L, Zeng R, Yang Z, Liu Q, Xu L, Kang D. The association between the environmental endocrine disruptor bisphenol A and polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

2018; 34: 370-377 [PMID: 29191127 DOI: 10.1080/09513590.2017.1405931]

89 Kandaraki E, Chatzigeorgiou A, Livadas S, Palioura E, Economou F, Koutsilieris M, Palimeri S, Panidis D, Diamanti-Kandarakis E. Endocrine disruptors and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): elevated serum levels of bisphenol A in women with PCOS.

2011; 96: E480-E484 [PMID: 21193545 DOI: 10.1210/jc.2010-1658]

90 Merhi Z, Kandaraki EA, Diamanti-Kandarakis E. Implications and Future Perspectives of AGEs in PCOS Pathophysiology.

2019; 30: 150-162 [PMID: 30712978 DOI: 10.1016/j.tem.2019.01.005]

91 Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Katsikis I, Piperi C, Kandaraki E, Piouka A, Papavassiliou AG, Panidis D. Increased serum advanced glycation end-products is a distinct finding in lean women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

2008; 69: 634-641 [PMID: 18363886 DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03247.x]

92 Tantalaki E, Piperi C, Livadas S, Kollias A, Adamopoulos C, Koulouri A, Christakou C, Diamanti-Kandarakis E. Impact of dietary modification of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) on the hormonal and metabolic profile of women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

2014; 13: 65-73 [PMID: 24722128 DOI: 10.1007/BF03401321]

93 Lee DH, Jacobs DR Jr. Methodological issues in human studies of endocrine disrupting chemicals.

2015; 16: 289-297 [PMID: 26880303 DOI: 10.1007/s11154-016-9340-9]

94 Xirofotos D, Trakakis E, Peppa M, Chrelias C, Panagopoulos P, Christodoulaki C, Sioutis D, Kassanos D. The amount and duration of smoking is associated with aggravation of hormone and biochemical profile in women with PCOS.

2016; 32: 143-146 [PMID: 26507209 DOI: 10.3109/09513590.2015.1101440]

95 Cupisti S, H?berle L, Dittrich R, Oppelt PG, Reissmann C, Kronawitter D, Beckmann MW, Mueller A. Smoking is associated with increased free testosterone and fasting insulin levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome, resulting in aggravated insulin resistance.

2010; 94: 673-677 [PMID: 19394003 DOI: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.03.062]

96 Faghfoori Z, Fazelian S, Shadnoush M, Goodarzi R. Nutritional management in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A review study.

2017; 11 Suppl 1: S429-S432 [PMID: 28416368 DOI: 10.1016/j.dsx.2017.03.030]

97 Zhang J, Liu XF, Liu Y, Xu LZ, Zhou LL, Tang LL, Zhuang J, Li TT, Guo WQ, Hu R, Qiu DS, Han DW. Environmental risk factors for women with polycystic ovary syndrome in china: a population-based case-control study.

2014; 28: 203-211 [PMID: 25001653]

98 He C, Lin Z, Robb SW, Ezeamama AE. Serum Vitamin D Levels and Polycystic Ovary syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.

2015; 7: 4555-4577 [PMID: 26061015 DOI: 10.3390/nu7064555]

99 ?agowska K, Bajerska J, Jamka M. The Role of Vitamin D Oral Supplementation in Insulin Resistance in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials.

2018; 10 [PMID: 30400199 DOI: 10.3390/nu10111637]

100 Moran LJ, March WA, Whitrow MJ, Giles LC, Davies MJ, Moore VM. Sleep disturbances in a community-based sample of women with polycystic ovary syndrome.

2015; 30: 466-472 [PMID: 25432918 DOI: 10.1093/humrep/deu318]