Observation of the exceptional point in superconducting qubit with dissipation controlled by parametric modulation?

Zhan Wang(王戰(zhàn)) Zhongcheng Xiang(相忠誠) Tong Liu(劉桐) Xiaohui Song(宋小會)Pengtao Song(宋鵬濤) Xueyi Guo(郭學(xué)儀) Luhong Su(蘇鷺紅)He Zhang(張賀) Yanjing Du(杜燕京) and Dongning Zheng(鄭東寧)

1Institute of Physics,Chinese Academy of Sciences,Beijing 100190,China

2University of Chinese Academy of Sciences,Beijing 100049,China

3Songshan Lake Materials Laboratory,Dongguan 523808,China

4China University of Geosciences,Beijing 100083,China

Keywords: exceptional point,parity-time-reversal(PT)symmetry,longitudinal field modulation

1. Introduction

In recent years, non-Hermitian systems with PT symmetry have attracted widespread attention because of their intriguing properties and potential applications in sensitive detection.[1]The PT symmetry can be realized by considering a coupled bipartite system with balanced gain and loss of energy or particles from the environment.[2]By varying the relative magnitude of the gain,loss and coupling strength,the system can show an unconventional transition between a PT symmetric phase and a PT broken phase at a so-called exceptional point (EP). At the EP, the eigenvalues of the non-Hermitian Hamiltonian, which describes the system, coalesce together and the corresponding eigenvectors also coincide at this point.Also,the breaking of the PT symmetry causes the eigenvalues of the non-Hermitian Hamiltonian to change from real to complex. The presence of the EP can lead to many peculiar physical phenomena, such as unidirectional invisibility,[3]nonreciprocal light propagation,[4–7]loss-induced suppression and revival of lasing.[8–10]More importantly, it is suggested that near the EP the system is more sensitive to external perturbations and this could give rise to enhanced sensing.[11,12]

EPs have been experimentally observed in different kinds of systems. Initially, it was mostly reported in semiclassical systems with balanced gain and loss, such as optical cavities,[11–14]microwave resonators[6,15–17]and mechanical oscillators.[18–20]More recently, work performed on quantum systems, such as cold atoms,[21–23]nitrogenvacancy centers,[24,25]superconducting circuits[26,27]and trapped ions[28,29]were reported. For the pure lossy quantum system,it has been shown that the lossy Hamiltonian could be mapped to a PT symmetric Hamiltonian and display passive PT symmetry breaking.[21,32]

In superconducting circuits, a single transmon qubit embedded in a 3D waveguide cavity is used to demonstrate the PT symmetry broken transition and the presence of EP.[26]The lowest three energy levels|g〉,|e〉, and|f〉of the qubit are involved. The first excited state|e〉and the second excited state|f〉are used to form the bipartite quantum system of investigation while the ground state|g〉is regarded as the environment. The key to the demonstration of the PT symmetry broken transition is a large and adjustable dissipation channel for a large decay rate of|e〉to|g〉. It is realized by inserting an impedance matching element(IME)between the cavity and the outside readout circuit. However,this method requires an additional element that may affect the performance of the entire qubit device.In this work,we demonstrate the observation of the PT symmetric broken phase transition and the EP on a frequency tunable superconducting Xmon qubit by parametric modulation of the qubit frequency that results in a controllable interaction between the qubit and a lossy readout resonator.This interaction transfers the qubit excitation to the resonator and, thus, creates a lossy channel controlling the decay rate of|e〉to|g〉. This approach of decay rate controlling with parametric modulation has been proposed in Ref.[30]and has been used for fast reset of superconducting qubits. It is simple and requires no additional hardware or modifications to the device components. It can be implemented easily on multi-qubit devices for the exploration of rich physics in non-Hermitian systems with PT symmetry.

2. Principle of the experiment

2.1. PT symmetry broken transition in a single dissipative qubit

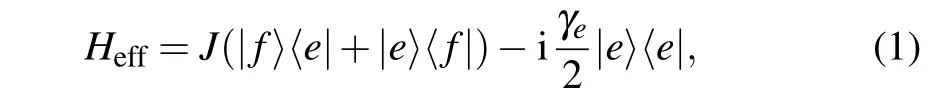

As shown in Ref.[26],a two-level non-Hermitian system with applied resonance driving and a loss term to the environment may be described by an effective Hamiltonian(ˉh=1)

where|e〉and|g〉denote the first and second excited states of the quantum system,respectively,andγeis the occupationnumber loss rate.This Hamiltonian may be rewritten asHeff=HPT?iγeI/4, whereHPT=Jσx ?iγeσz/4 is a PT-symmetric Hamiltonian,andIis the identity matrix,σx(z)is the Pauli matrix,Jσx=J(|f〉〈e|+|e〉〈f|) when we just consider the|e〉state and the|f〉state. The complex eigenvalues ofHeffhave different imaginary components atJ<γe/4,and the system is in the PT broken phase. At a stronger coupling,past the EP atJ0=γe/4, the imaginary components for the two dissipative eigenmodes coincide, and the system is in the PT symmetric(unbroken) phase. To implementHeff, we require the respective energy decay ratesγe ?γf.

2.2. Qubit decay rate control

We consider a generic system with a two-level atom(with transition frequencyωq) coupled to a resonator (with frequencyωr). If the effective coupling isgeff, the Hamiltonian(ˉh=1)of this coupled system in the Jaynes–Cummings model is

wherea,a+,σ?,σ+are lowering and raising operators of the resonator and the qubit, respectively, andσzis the Pauli matrix. Considering the dissipation, the dynamics can be described by the following Lindblad master equation:

The above formula shows thatγecan be tuned by varyinggeand the frequency detuning ?ω. Obviously, theγeshows maximum when ?ω=0.

2.3. Longitudinal field modulation

For a single Xmon,we realize qubit frequency parametric modulation by applying a longitudinal field modulation(LFM)with frequencyωzand amplitudehz. In the laboratory coordinate system,the Hamiltonian(ˉh=1)of the qubit system with LFM and transverse resonance driving is

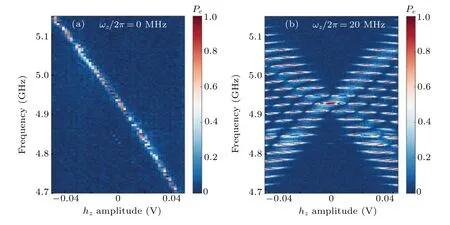

whereJnis thenth-Bessel functions of the first kind. It shows,with the LFM applied on the qubit,sidebands appear atωq?nωz(n=0,±1,±2,...). Another feature of the Hamiltonian is that the Rabi oscillation term may disappear whenJn(α)=0.In Fig.1,we show the measured qubit energy spectrum with and without LFM. The measurements are taken atωq/2π~4.92 GHz andωz/2π=0,20 MHz.

Fig.1. Measured qubit energy spectrum(a)without and(b)with LFM.The qubit is biased at 4.92 GHz. The modulation frequency is ωz/2π =20 MHz.

3. Experimental setup

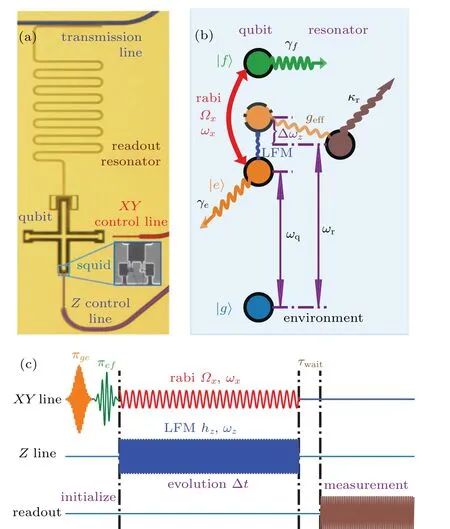

In the experiment, we realize a non-Hermitian system with PT symmetry on a frequency tunable superconducting Xmon qubit. Figure 1(a) shows an optical photograph of the device. The qubit is formed by a DC-SQUID (the enlarged region in the graph)shunted by a cross-shaped capacitor. The Xmon qubit can be regarded as an anharmonic oscillator exhibiting a series of unequally spaced energy levels that can be individually addressed with microwave pulses via theXYcontrol line. A magnetic flux applied to the SQUID loop through theZcontrol line can tune the energy level spacing. The qubit is capacitively coupled to a readoutλ/4 resonator that is also coupled to a microwave transmission line. When the fundamental mode frequency of the resonator is substantially larger than the qubit transition frequency between the lowest two levels,the dispersive interaction between the qubit and the resonator results in a state-dependent shift in the resonator frequency.Thus,in this dispersive readout scheme,the qubit state information can be obtained by measuring the transmission or reflection coefficients of the transmission line.

Following the scheme of Ref. [26], we use the first two excited states of|e〉and|f〉to form a two-level system and regard the ground state|g〉as the environment. By applying a coherent resonate drive(Rabi drive)of variable amplitude,the coupling between|e〉and|f〉can be realized. To observe the PT symmetry broken transition and the EP, we need to introduce controllable losses of the system energy to the environment in such a way that the decay rate of the state|e〉(γe)is much larger than that of the state|f〉(γf). This can be realized by parametric modulation of qubit frequency using LFM as discussed in Subsection 2.3. In other words, when the frequency of one sideband is in resonance with the readout resonator, the decay through the lossy readout resonator is maximized. By varying the LFM frequency and amplitude,the decay can be adjusted. Meanwhile, we vary the driving amplitudeΩx,which means changing the coupling strengthJ,so that the PT symmetry broken transition can be observed.The schematic of this process and the corresponding pulse and waveform sequence are shown in Figs.2(b)and 2(c).

Fig. 2. (a) Optical graph of a frequency tunable superconducting Xmon qubit. (b)Experiment schematic diagram for the observation of the PT symmetry broken transition and the EP.In the diagram,γe,γf,κr represents the decay rate of the states|e〉,|f〉and the resonator,respectively. The geff and?ω are the effective coupling strength and detuning between the resonator and the qubit after applying longitudinal field modulation(LFM).Ωx is the amplitude of Rabi driving while ωx is the frequency. ωr and ωq are the frequencies of the resonator and the qubit (energy level between the state |g〉and|e〉),respectively. (c)Pulse and waveform sequence of the experiments.

To ensure that the experimental conditions meet the theoretical requirements,characterization work needs to be carried out at first. Initial state preparation and readout are carried out at an idle frequency point, corresponding toωge/2π=5.69378 GHz andωfe/2π=5.4411 GHz. The anharmonicity is about 252.67 MHz. The readout resonator frequency is about 6.6178 GHz and it differs from theωge/2πby 924 MHz.The readout resonator frequency shift 2χgeis about 0.55 MHz when the qubit is excited from|g〉to|e〉while the shift 2χe fis about 0.4 MHz for|e〉to|f〉excitation. The coupling strength between the qubit and the readout resonator may be calculated from the shift value and is found to be~48.7 MHz. With the AC stark effect measurements,the decay rate of photons in the readout resonatorκris~6 MHz.

Fig.3. (a)Transmission data measured when the qubit is in|g〉,|e〉and|f〉states,respectively. (b)Transmission data taken at a fixed frequency marked by the dashed line in(a).

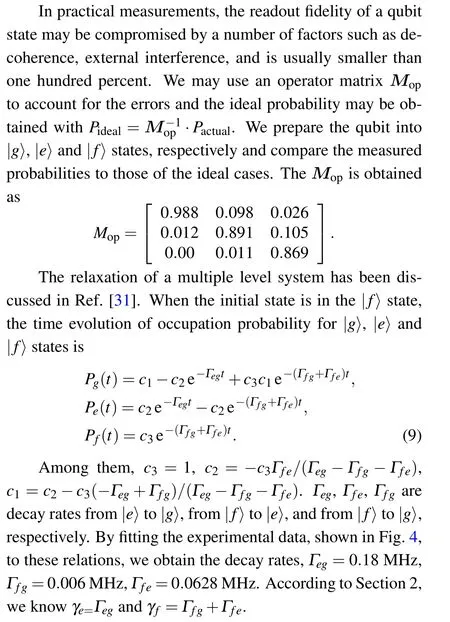

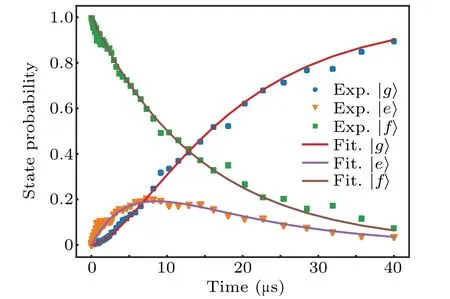

In addition to the above parameters, the decay rates of the excited statesγeandγf(representing decaying from the|e〉and|f〉states to environment) are of significance in the study of the non-Hermitian system. To characterizeγeandγf,we need to firstly readout and distinguish the different states.According to the dispersive readout theory,we know that different qubit states correspond to different frequency shifts of the readout resonator frequency. In this way, we can distinguish the three states of interest|g〉,|e〉and|f〉. The data are shown in Fig.3. We use oneπpulse or two sequentialπpulses to prepare the qubit into|e〉and|f〉states,respectively.The transmission data measured on the readout transmission line are shown in Fig. 3(a). Clearly, the resonant frequency shows a state-dependent shift(Note,the frequencies displayed on the horizontal axis are the values after down conversation.The actual value should be added 6.61 GHz,the local oscillation frequency). In Fig. 3(b), we show the transmission data measured at a fixed frequency(as marked by the black dashed line) in theI–Qpolar plane. The frequency is chosen so that the distinction of the three states is clear.

Fig. 4. Relaxation data measured for the three states |e〉, |g〉 and |f〉.The solid curves are fitting to Eq.(9).

4. Experimental control of qubit decay rate

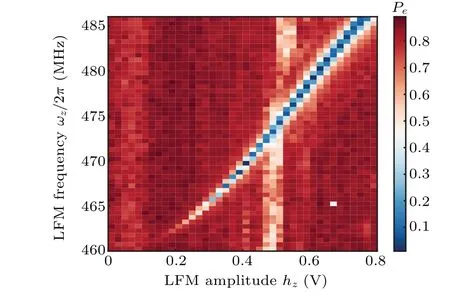

According to Section 2, changing the coupling strength and detuning frequency between the qubit and resonator by LFM leads to the changing of the qubit decay rate.This means that we can control the qubit decay rate by changing the amplitude and frequency of LFM.In our experiments,the bandwidth of theZcontrol line is limited to 0–500 MHz while the readout resonator frequency is 924 MHz greater than the quibt transition frequency when biased at the idle point. Thus, we may apply a LFM with modulation frequency around 462 MHz to achieve a largeγe. This corresponds ton=2 in Eq. (8). We prepare the qubit to the|e〉state before applying LFM for 1μs and finally measure the probability of state|e〉,Pe.We vary the LFM amplitude and frequency progressively to find the dependence of the decay rate on the LFM frequency and amplitude.The data are shown in Fig.5 and the strip-like region with very lowPe,and hence largeγe,is clearly identified.

When LFM is applied at the sweet point of the qubit,there is a DC bias component acting on the qubit, resulting in the amplitude and frequency dependence of the lowPeregion shown in Fig.5. If LFM is applied away from the sweet point,the lowPeregion should be less frequency dependent.

Fig.5. The Pe data corresponding to different LFM hz and ωz.

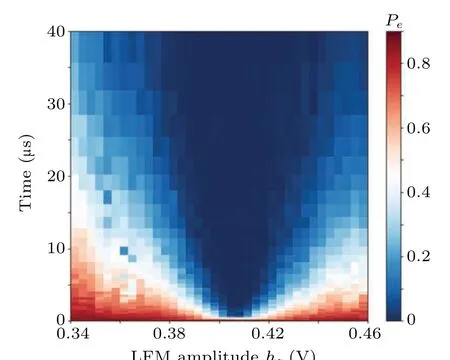

Fig.6. Color map of Pe versus t for various values of hz.

To show more clearly thatγechanges with LFM, we fix a modulation frequencyωz=470 MHz/2πand measure theγefor each modulation amplitudehz. The result is shown in Fig.6,and it is clear to see thatγechanges withhz.

After showing that theγechanges withhz,we should also verify thatγfdoes not change withhz. As discussed in Section 3,we prepare the qubit to the state|f〉,and wait for some time,finally measure the probability of|g〉,|e〉,|f〉states,respectively. During the waiting time, the longitudinal field is applied through theZcontrol line. According to Eq. (9), we can getγeandγfby fitting the probability data of|g〉,|e〉,and|f〉states. Data shown in Fig.7 confirm that the change ofγfis small when LFM is applied. The red solid line is the fitting curve using Eq. (5). Note that thex-axis variable in Fig. 7 is?ω,the detuning of the qubitn=2 sideband frequency to the readout resonator. In our experiments, the qubit is biased at the sweet point, thus the change of LFM amplitudehzwould also result in a change in ?ω. However,if the change ofhzis small,the relation between the two is approximately linear.

Fig.7. The experiment results of γe and γf obtained by fitting the original relaxation data,similar to those shown in Fig.4.

5. Quantified EP by oscillation frequency

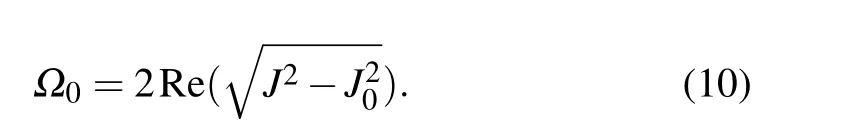

To observe PT symmetry broken transition, we choose a working point at whichγeis much larger thanγf.Similar to the procedure described in Ref.[26],we applyπg(shù)eandπefpulses to prepare the qubit to state|f〉and then apply a coherent microwave driving in resonance with the|e〉and|f〉transition frequency and with amplitudeJthrough theXYcontrol line.In the same time, a LFM is also applied to the qubit via theZcontrol line so thatγeis about 2.06 MHz andγfis about 0.08 MHz. Finally,after a period of timet,we switch off the driving field and LFM,and measure the occupation probability of state|f〉Pftogether with the probability of the state|g〉and|e〉. The schematic diagram of the whole process is shown in Fig.2(c). As discussed in Subsection 2.1,whenJ>γe/4,the system is in the PT symmetric phase andPfwould oscillate at a frequency

At the EP,J=γe/4,the oscillation disappears.

Because we consider only the system formed with|e〉and|f〉,we use the normalized probabilityPnf=Pf/(Pf+Pe)dynamics of the system. The results are displayed in Fig. 8. In Fig. 9(a), more detailed data are shown and the time dependence ofPnffor two differentJvalues (as marked by dashed lines in Fig. 9(a)) is given in Fig. 9(b). The solid lines are the fitting curves using a cosine function with exponentially decayed amplitude. Clearly, whenJis large, we observe the oscillatory behavior ofPnfand the oscillation disappears whenJis reduced below a certain value.

Fig.8. Color map of Pnf versus t for various values of J.

Fig.9. (a)More detailed of Pnf evolution data measured under the same condition as in Fig.8. (b)The Pnf versus time and the fitting plot for two values of J(J=106,green dot;J=0.44,blue dot).

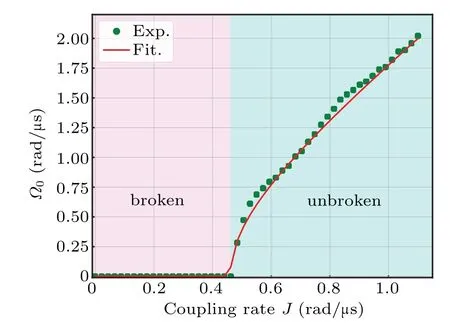

In Fig. 10, the oscillation frequencyΩ0obtained by fitting is exhibited as a function of coupling strengthJ. The point at whichΩ0becomes zero is the EP. Further reducingJ, the system is in the PT broken phase. The solid red line is the fit to Eq. (10). The data show that, at the EP,J0is about 0.46 rad/μs, being consistent with the value 0.51 rad/μs obtained fromγe/4.

Fig.10. Variation of oscillation frequency Ω0 with coupling strength J.

6. Quantified EP through all parameter regions

It has been pointed out that to accurately determine the location of EPs in experiments by measuring the asymptotic behavior of the energy around the EP without special prior knowledge is difficult.[29]Indeed, the evolution ofPfunderHeffgives an exponential decay that makes the determination ofΩ0become increasingly difficult when approaching the EP.To solve this problem, an alternative scheme of determining EP using all parameter regions has been proposed.[29]Here we also use this scheme in our experiments of superconducting qubits.

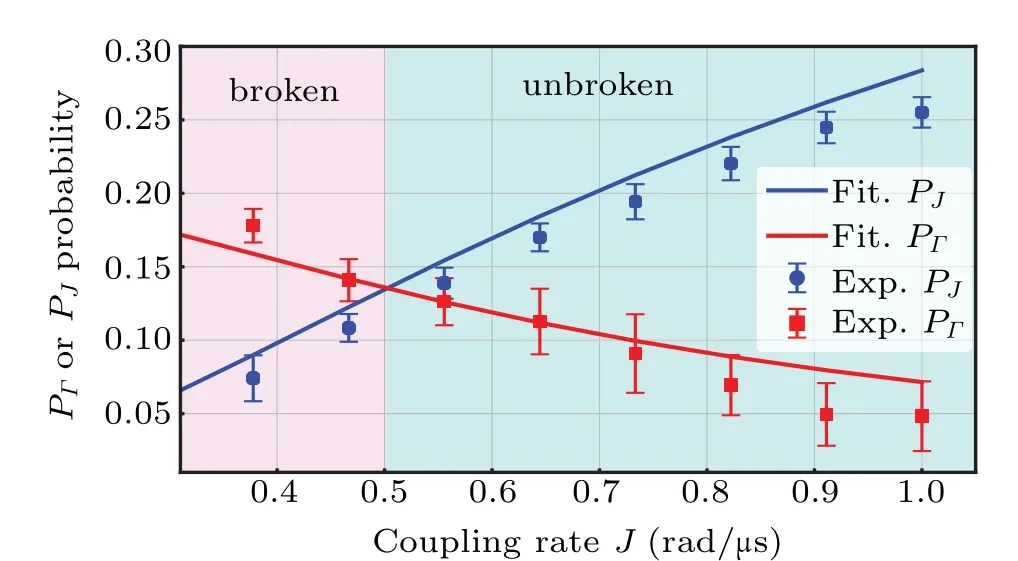

Fig. 11. Determination of EP from the measurement of PJ (blue) and PΓ (red).

The specific operation and measurement procedures are as follows. (i) Prepare the initial state to|f〉and let the system evolve for a period of timet. Then we measure the probability of state|e, 〉PJ(t). (ii) Repeat the procedure for the initial state(|f〉+|e〉)/2 and measure the probability of state(|f〉?|e〉)/2,PΓ(t). (iii) We repeat (i) and (ii) for different values of the coupling strengthJand lett=1/J. The data are displayed in Fig.11. The solid curves are fitting to the theoretical expression given in Ref.[29]which suggests that the cross point ofPJandPΓis the EP.At this point, we haveJ0~0.5,being also consistent with the value obtained in Fig.10.

This method does not need to fit the oscillation frequency to determine the EP. However, it utilizes information of all three states and hence requires better readout calibration of the three states and the fidelity of the operation.

7. Dependence of EP position on the decay rate

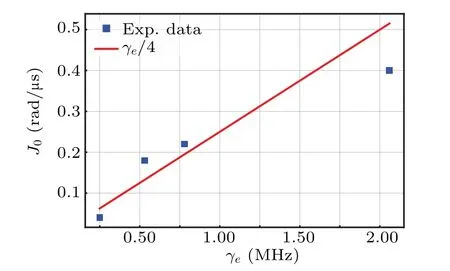

According to Subsection 2.1, the position of the EP should vary with the decay rateγe. We make measurements for four different values ofγeand determine the corresponding EPs.The position of EPJ0is shown in Fig.12.The agreement between experiment points andγe/4 is reasonable.

Fig.12. Dependence of EP position J0 on the decay rate γe.

8. Conclusion

We utilize a previously reported dissipation control technique for frequency tunable superconducting transmon qubits[30]to investigate the PT symmetric phase transition of non-Hermitian quantum system and determine the corresponding EP.The non-Hermitian quantum system is formed with the first and the second excited states of the qubit. We show that the dissipation rate of the first excited state of the transmon qubit could be tuned by parametric modulation of the qubit frequency. The parametric modulation effectively changes the coupling strength between the qubit and its lossy readout resonator.By varying the coupling between the two excited states of the qubit,the PT phase transition is observed. Two methods are used to determine the EP and the results are in agreement with that calculated by the theory.

Our study demonstrates a possible new approach for further investigation of the remarkable phenomena of non-Hermitian systems in the vicinity of the EP.Furthermore, the approach can be implemented on multi-qubit devices to investigate the properties of many-body non-Hermitian systems and to explore the high-order EPs.

- Chinese Physics B的其它文章

- Physical properties of relativistic electron beam during long-range propagation in space plasma environment?

- Heterogeneous traffic flow modeling with drivers’timid and aggressive characteristics?

- Optimized monogamy and polygamy inequalities for multipartite qubit entanglement?

- CO2 emission control in new CM car-following model with feedback control of the optimal estimation of velocity difference under V2X environment?

- Non-peripherally octaalkyl-substituted nickel phthalocyanines used as non-dopant hole transport materials in perovskite solar cells?

- Dual mechanisms of Bcl-2 regulation in IP3-receptor-mediated Ca2+release: A computational study?