Variation in water source of sand-binding vegetation across a chronosequence of artificial desert revegetation in Northwest China

YanXia Pan,XinPing Wang,Rui Hu,YaFeng Zhang,Yang Zhao

Shapotou Desert Research and Experiment Station,Northwest Institute of Eco-environment and Resources,Chinese Academy of Sciences,Lanzhou,Gansu 730000,China

ABSTRACT Water is the most important limiting factor in arid areas, and thus water resource management is critical for the health of dryland ecosystems. However, global climate change and anthropogenic activity make water resource management more difficult,and this situation may be particularly crucial for dryland restoration,because of variation in water uptake patterns associated with artificial revegetation of different ages and vegetation type. However, there is lacking longterm restorations that are suitable for studying this issue. In Shapotou area, Northwest China, artificial revegetation areas were planted several times beginning in 1956, and now form a chronosequence of sand-binding landscapes that are ideal for studying variability in water uptake source by plants over succession. The stable isotopes δ18O and δ2H were employed to investigate the water uptake patterns of the typical revegetation shrubs Artemisia ordosica and Caragana korshinskii,which were planted in different years.We compared the stable isotope ratios of shrub stem water to groundwater,precipitation,and soil water pools at five layers(5-10,10-40,40-80,80-150,and 150-300 cm).The results indicate that Artemisia ordosica derived the majority of their water from the 20-150 cm soil layer, whereas Caragana korshinskii obtained water from the 40-150 cm soil layer.The main water sources of Artemisia ordosica and C.korshinskii plants changed over time, from deeper about 150 cm depth to shallow 20 cm soil layer.This study can provide insights into water uptake patterns of major desert vegetation and thus water management of artificial ecosystems, at least in Northwest China.

Keywords:artificial vegetation;stable isotopes;soil water;xylem water;water source

1 Introduction

Water is the most important limited factors in arid desert region, which control the survival and development of animals and plants in desert areas. The field hydrological cycle is complex, with many compartments and interactions between biological and physical processes (Vargaset al., 2017) as water moves from the soil, through terrestrial vegetation, out into the surrounding atmosphere (Nobel, 2009), and back again into the soil. Spatial and temporal variation in water use by plants influences the state and availability of water resources within a catchment, and thus the magnitude and timing of surface and ground water flows. This process is further complicated when plants change their water source over time (McCole and Stern, 2007; Eggemeyeret al., 2009) or space(Grieset al., 2003; Dudleyet al., 2014). Thus, a mechanistic understanding of the processes that determine how vegetation uses potential water sources is vital for quantifying the effects of vegetation on the local water cycle.This issue is especially important in arid and semiarid ecosystems, where the use of limited water resource determines the direction of vegetation succession(Wanget al.,2017).

As an integral part of both the global hydrological and carbon cycles, in any one year the earth's vegetation transpires more than twice the amount of water vapour present in the atmosphere (Hervé-Fernándezet al., 2003) and processes ca. 120 Gt carbon through photosynthesis (Beeret al., 2010). Changes in the functioning of vegetation therefore affect these cycles(Boothet al., 2012). In particular, the establishment of artificial vegetation in desert areas can impact local water cycles, largely through increased interception and deeper rooting depths (Wanget al., 2013; Zhanget al., 2016). Water is generally taken up by roots(with important exceptions; see Goldsmith, 2013), so root structure and function play a central role in plantwater relations. Traditional methods used to determine plant water uptake are based on phenological traits, rooting systems, and field positioning experiments and observations (Wanget al., 2008; Zhanget al.,2008b;Huanget al.,2015;Panet al.,2015).However, advances in the application of stable isotopes to hydrological and ecological studies now allow indepth study of a plant's water uptake strategies.

In contrast to traditional methods, isotopes can trace the activity of deep roots from various available surface and sub-surface pools (Dudleyet al., 2018).The stable isotopes δ18O and δ2H are useful indicators of water movement and the hydrological cycle in general (Gatet al., 1996). These isotopes are able to successfully identify the source of transpired water by a simultaneous comparison of the isotopic compositions of xylem and source water (Dawson and Ehleringer, 1991). Based on the assumption that no isotope fractionation occurred during root water uptake and plant water transport in most plants(Zimmermannet al., 1967; Dawson and Ehleringer, 1991;Ehleringer and Dawson,1992),xylem water can be regarded as a mixture of several water sources. Therefore, it is feasible to determine the main water source for revegetation growth by comparing the isotopic composition of xylem water and source water.A similar isotopic composition of xylem water and other water sources indicates the main water uptake source(Wanget al., 2010; Yanget al., 2015). Sources from which plants take up water (soil water at different depths, fog, dew, or groundwater) usually have different isotopic compositions because of evaporative fractionation (Dawson and Pate, 1996) and the rainout effect (Brookset al., 2010). The uptake of water by roots generally involves little fractionation (but there are exceptions; see Ellsworth and Williams, 2007).Thus, the source of xylem water can often be identified by comparing pools with contrasting isotopic signatures(Dawson and Ehleringer,1991).

Stable isotope methods can reveal water uptake patterns and accurately trace water movement, with the advantage of being non-destructive (Paces and Wurster, 2014; Ma and Song, 2016). However, recent research has shown ambiguities in identifying the vegetation water source,depending on whether a dual isotope analysis or a single isotope mixing model approach is used (Bowlinget al., 2017). While dual stable isotope approaches have applications for assessing the degree to which vegetation affects catchment water flows, only a handful of studies of this type have been undertaken in a desert revegetation area.

Increasing attention has been paid to plant water uptake using stable isotopes in desert ecosystems(Wuet al., 2014; Daiet al., 2015), but this issue is far from being fully understood. Past research in this area failed to identify specific water sources, as well as temporal and spatial variation in the use of each water source. A better understanding of the sources and magnitudes of desert plant water uptake can greatly help in making optimal choices for desert water management. Shapotou area, located in Northwest China,is a typical revegetation desert area.Artificial restoration began in 1956, which changed the local water cycle. However, the uneven distribution of precipitation makes water uptake by plants highly temporally heterogeneous at this site and the effects of physiological characteristics of revegetation on water uptake remain unclear, especially in different successional stages.

In northern China, the wind-sand hazard area is approximately 320,000 km2(Liet al., 2014). Here,the establishment of sand-fixing vegetation is an effective method for preventing desert encroachment (Liet al., 2017). Over the past 60 years, we have established artificial sand-binding vegetation on 6,000,000 hm2of wind-blown sand hazard areas, serving as an important ecological barrier to further desertification (Wanget al., 2007; Good and Caylor, 2011). Two widely used sand-binding plants areArtemisia ordosicaandCaragana korshinskii, which have distinct water uptake patterns because of their different root systems and phenology of resource use. Field measurements show that most roots ofCaragana korshinskiiare distributed between 0.3 m and 2.0 m depth, while those ofArtemisia ordosicawere found between 0.1 m and 1.0 m(Zhanget al.,2008a).

In this study,we used a hydrogen and oxygen dual stable isotope approach to examine the isotopic signatures of precipitation, groundwater, and soil water at different depths and xylem water for two typical sand-fixing shrubs in different revegetation succession areas. The specific objectives of our study are: 1) to identify the main layers of water uptake byArtemisia ordosicaandCaragana korshinskiiin different successional stages; 2) to calculate the contributions to water uptake from each water source at different successional stages forArtemisia ordosicaandCaragana korshinskii; and 3) to optimize current revegetation plant management practices.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study site

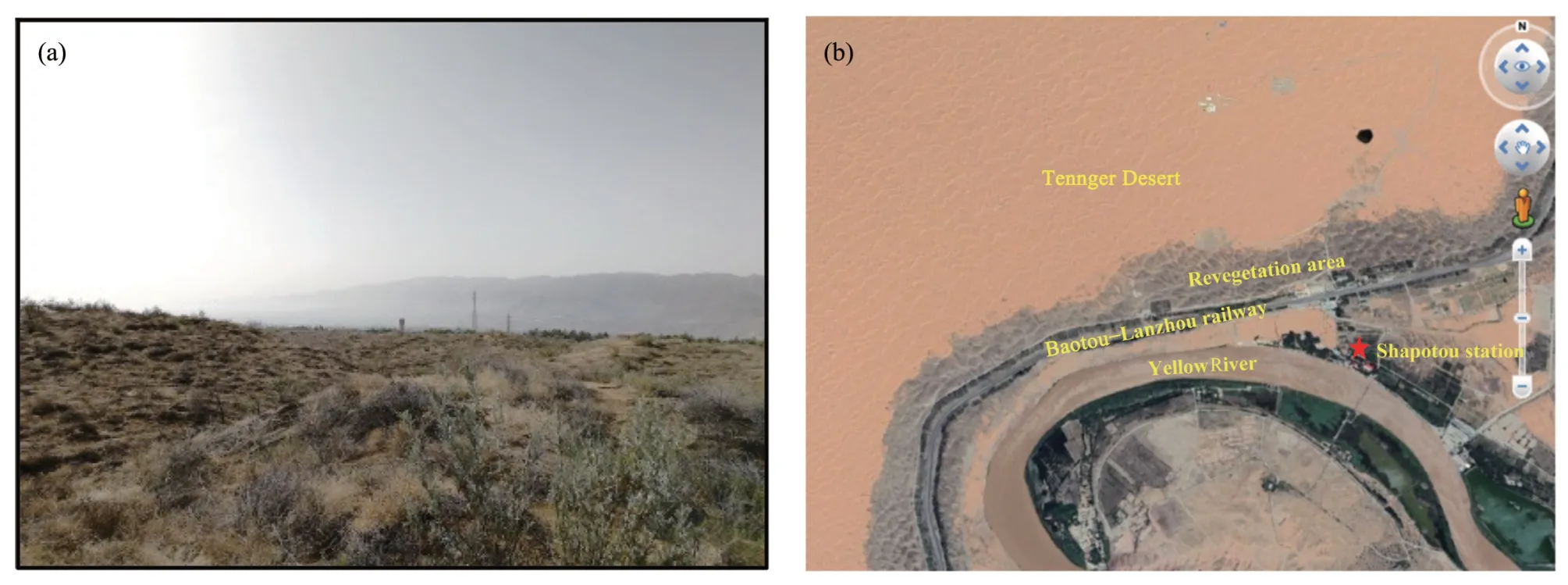

The study was conducted in the Shapotou Desert Experimental Research Station, which borders the Tengger Desert(37°27′N,104°57′E)with an elevation of 1,339 m a.s.l.. The natural landscape is characterized by reticulated chains ofbarchansdunes with a vegetation cover of less than 1%. The mean annual precipitation is about 180 mm with large seasonal and interannual variation.

To stabilize the moving sand dunes,straw checkerboards (spacing 1m×1m) were firstly established by inserting straw vertically into the soil to a depth of 15-20 cm,so that it protruded approximately 10-15 cm above the dune surface. The straw checker-boards structures remain intact for 4-5 years. Revegetation experiments were carried out along the rail line from Baotou to Lanzhou. Xerophytic shrubs (e.g.,Salix gordejevii,Calligonum arborescens,Atraphaxis bracteata,Caragana korshinskii,Artemisia ordosica, andHedysarum scoparium) were then planted in straw checker-board plots. The unirrigated vegetation system was established in 1956 and extended in 1964,1973, 1981, and later (Wanget al., 2006; Liet al.,2007). So far, a desert shrub ecosystem with dwarf shrubs and a biological soil crust has formed on the stabilized sand dunes. Spatial heterogeneity of the study area is high and characterized by patches of perennial vegetation, of whichCaragana korshinskiiKom.(Fabaceae)andArtemisia ordosicaKrasch.(Asteraceae)are two typical shrubs(Figure 1).

Figure 1 Tennger Desert and location of the study site.The map shows the location of the Shapotou Station,Yellow River,revegetation along the railway and the extent of the Tennger Desert,as well as an inset showing the general landscape characteristics around the study area

2.2 Sample collection and isotope analysis

The experiment was carried out from May to September, 2017 in different year artificial revegetation area (Figure 1). Groundwater samples were collected from a well near the experimental field.The river water sample was collected from the nearby Yellow River. Precipitation was collected immediately after a rain event to minimize evaporation effects. All water samples were collected three times repetitively.

To examine differences in water sources between different ages of sand-fixed landscapes, plant xylem and soil samples at different depths forCaragana kor-shinskiiandArtemisia ordosicawere collected at different revegetation successional stages (where the revegetation was established in 1956,1981,1991,2010,and nearby natural vegetation). Three similar shrubs were chosen for each species in each revegetation area. Xylem was dissected from plants and the epidermis was gently removed using tweezers. Soil samples were collected from layers at 0-5,5-10,10-20,20-40,40-60,60-80,80-100,100-150,150-200,200-250 and 250-300 cm using a 10 cm diameter auger.Three plants and soil samples were collected for each shrub.Soil water could only be extracted at 0-110 cm depth in the 1956 revegetation area because it was too dry at deeper soil layers.

All samples were quickly placed into 20 mL screw-cap glass vials sealed with parafilm and stored in a refrigerator at -4 °C until extraction.All soil water isotope samples were collected in duplicate. Water in xylem and soil samples was extracted using a fully automatic vacuum condensation extraction system(LI-2100, LICA United Technology Limited, Beijing,China). The extraction rate of water from samples was >98%. Xylem water, soil water, underground water, and precipitation (0.5-1.5 mL) were analyzed for δ18O and δ2H (Los Gatos Research, Inc.).The isotopic compositions were analyzed using an Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (MAT 253, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., USA). The isotopic compositions were reported in standard δ-notation, representing ‰ deviations from the Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water standard (V-SMOW), expressed as δ(‰ ) = (Rsample-Rstandard)/Rstandard× 1000 = (Rsample/Rstandard-1) × 1000. The analytical uncertainty for δ18O was 1‰ and for δ2H was 0.2‰. Corrections using a standard curve for δ18O and δ2H in xylem water samples were conducted to avoid methanol and ethanol contamination (Schultzet al.,2011).

2.3 Data analysis

The Bayesian mixing model (MixSIR 1.0.4) was employed to quantify the proportion of water uptake from each water source based on the mass balance of the isotope (Moore and Semmens, 2008).A one-way analysis of variance with Duncan's post-hoc test (p≤0.05)was conducted to test for differences in δ18O and δ2H among different soil layers and each soil layer of different revegetation areas forArtemisia ordosicaandCaragana korshinskii.Prior to analysis,all of the variables were checked for normality (Shapiro-Wilk test)and homogeneity (Levene test). All statistical analyses were performed using the software SPSS (SPSS Inc.,Chicago,IL,USA).

3 Results

3.1 Meteorological conditions

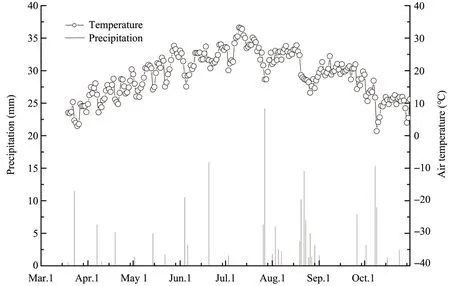

The total precipitation in 2017 was 193.8 mm,more than 67% of which fell during June to September (Figure 2).The mean air temperature was 11.4 °C over the year. Heavy precipitation and a high air temperature occurred simultaneously.

Figure 2 Daily precipitation(vertical lines,left axis)and air temperature(open circles,right axis)during the study period in 2017

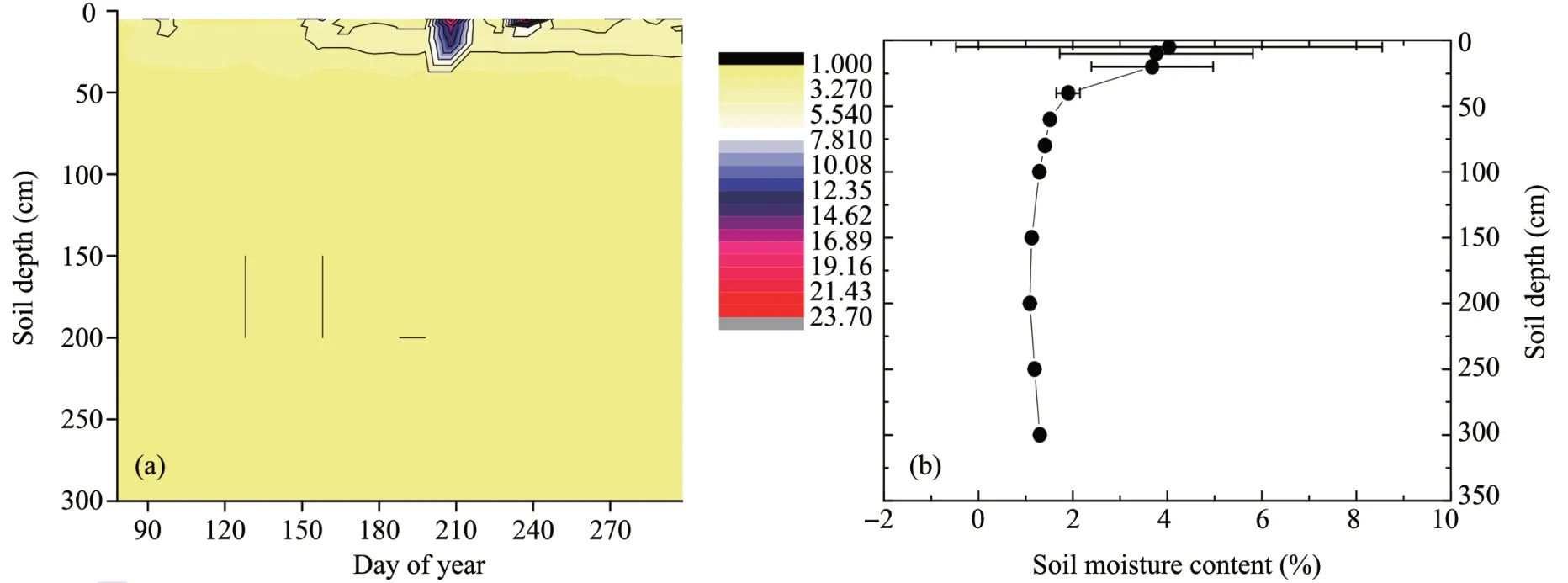

3.2 Soil volumetric water content

The soil volumetric water content was characterized by stratification (Figure 3). First, the average soil moisture content in the 0-20 cm layer was significantly higher than the other soil layers (p<0.01). Second,the temporal variability of soil volumetric water content was greater above the 50 cm layer, which was influenced by precipitation (the standard deviation was larger). Beneath this layer, the variation in soil moisture content was minimal.

3.3 The isotope composition characteristics of different water sources

Isotopic values from precipitation for δ18O(mean =-54.83‰, range =-107.93‰ to 23.33‰) and δ2H (-7.33‰, -14.73‰ to 9.57‰) during the study period showed a greater range than the range of isotopic values found in the soil (-74.98‰ to 6.44‰ for δ2H and -11.8‰ to 9.11‰ for δ18O). The liner relationship between δ18O and δ2H was called meteoric water line, local meteoric water line (LMWL) is the foundation of regional water cycle research (Craig,1961). The local meteoric water line was obtained from experiment area precipitation samples and could be expressed as δ2H = 7.83 × δ18O + 3.08 (R2= 0.92,p<0.01).

Figure 3 (a)Daily average soil volumetric water content during the study period in 2017.Different colors represent different soil volumetric water content.(b)Mean soil water content at each soil depth during the whole observation date.Bars denote standard deviation

Isotope ratios of xylem water were similar to the integrated values of the soil water isotope ratios. UnderCaragana korshinskii, δ2H for xylem water was-50.98‰ and for soil water was -41.26‰; δ18O for xylem water and soil water were both -3.91‰. UnderArtemisia ordosica, δ2H for xylem water was-45.84‰ and for soil water was -35.15‰; δ18O for xylem water was - 2.40‰ and for soil water was-3.39‰.The δ2H-δ18O relationship inCaragana korshinskiixylem water could be expressed as δ2H =3.42 × δ18O -37.63 (R2= 0.73,p<0.01), and inArtemisia ordosicaas δ2H =3.48 × δ18O -37.48(R2=0.63,p<0.01), which was called the xylem water line(XWL). The highest and lowest isotopic compositions of soil moisture occurred at 5 cm and 110 cm,respectively(Figure 4).

Figure 4 Water isotopes(δ18O and δ2H)of bulk soil water,xylem water,underground water,and average precipitation during the study period.Soil water and xylem isotopes were collected on two different dates(May 24 and September 6)from five revegetation plots.LMWL represents the local meteoric water line(LMWL,dashed line,based on precipitation data during the study period,δ2H=7.83 × δ18O+3.08,R2=0.92,p <0.01);GMWL is the global meteoric water line(GMWL,solid line,δ2H=8 × δ18O+10);XWL is the xylem water line(XWL)

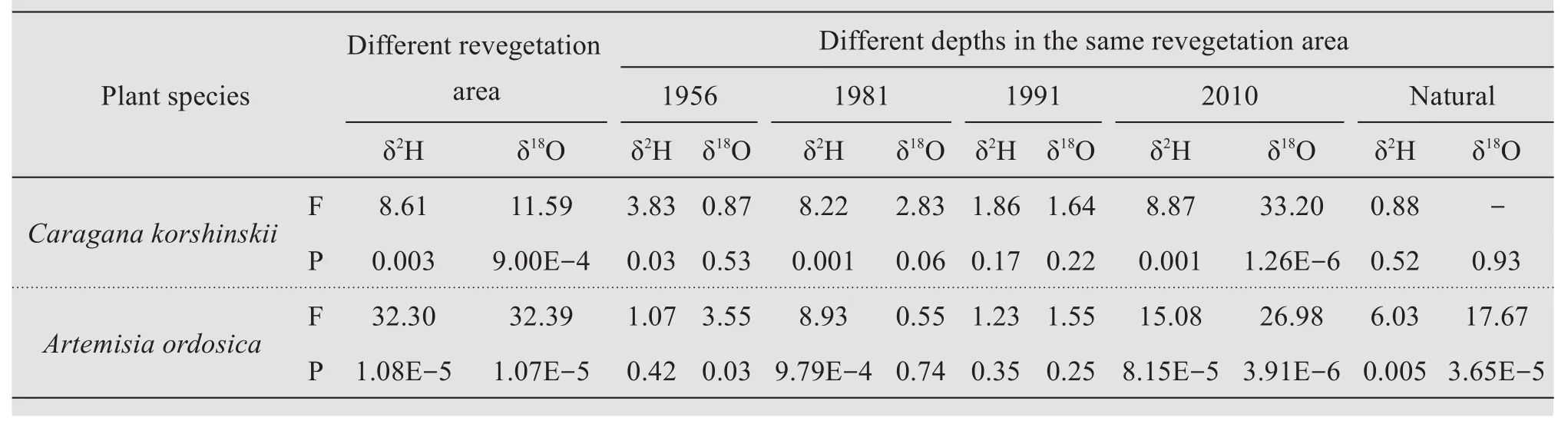

The δ2H and δ18O values of soil water underCaragana korshinskiiandArtemisia ordosicawere both significantly different in different revegetation areas(ANOVA,p<0.01, Table 1). For different revegetation areas, the effect of soil depth on soil water δ2H and δ18O values was different. The soil water δ2H and δ18O values were not significantly different in the 1956 and 1991 areas for bothCaragana korshinskiiandArtemisia ordosicaplants (p>0.01), whereas the difference was obvious in the 2010 revegetation area.For water in different soil layers underCaragana korshinskiiandArtemisia ordosicaplants in the 1981 revegetation area,δ2H was different but δ18O was not.In the natural revegetation area, δ2H and δ18O values were not significantly different for water in the different soil layers underCaragana korshinskiiplants, but were all significantly different for water underArtemisia ordosicaplants(Table 1).

Table 1 Results from the ANOVA analysises of soil water(0-110 cm)stable isotopes(δ18O and δ2H)from different revegetation areas of the chronosequence(A)or different soil water layers within the same area

3.4 Identifying the relative contribution of water pools to water uptake of revegetation plants

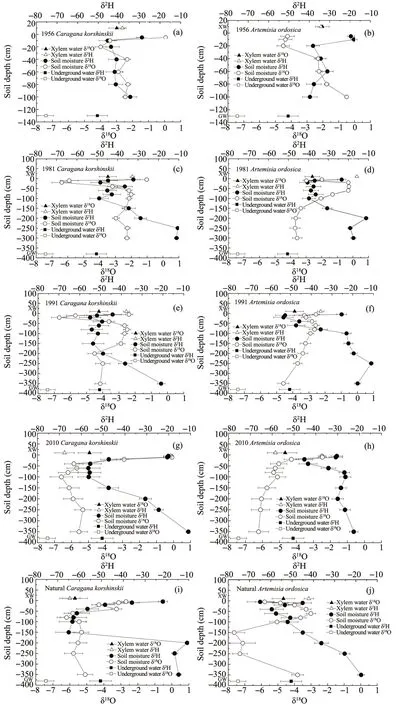

The δ18O and δ2H values varied between xylem water, soil water, and underground water underCaragana korshinskiiandArtemisia ordosicaplants of different successional stages (Figure 5). ForCaragana korshinskiiplants, the δ18O of xylem water was similar to the 40-100 cm soil layer in the 1956 revegetation area(Figure 5a),the 60-100 cm soil layer in the 1981 year revegetation area(Figure 5c),the 60-150 cm soil layer in the 1991 year revegetation area (Figure 5e),the 60-200 cm soil layer in the 2010 year revegetation area (Figure 5g), and the 60-250 cm soil layer in the natural revegetation area(Figure 5i).The δ2H of xylem water was similar to the 40-80 cm soil layer in the 1956 revegetation area (Figure 5a), the 60-80 cm soil layer in the 1981 revegetation area (Figure 5c), the 40-150 cm soil layer in the 1991 revegetation area(Figure 5e), the 40-100 cm soil layer in the 2010 revegetation area (Figure 5g), and the 60-150 cm soil layer in the natural revegetation area(Figure 5i).

ForArtemisia ordosicaplants, the δ18O of xylem water was similar to the 40-60 cm soil layer in the 1956 year revegetation area (Figure 5b), the 40-80 cm soil layer in the 1981 year revegetation area (Figure 5d), the 40-80 cm soil layer in the 1991 year revegetation area(Figure 5f),the 40-100 cm soil layer in the 2010 year

revegetation area (Figure 5h), and the 40-80 cm soil layer in the natural revegetation area (Figure 5j).The δ2H of xylem water was similar to the 40-60 cm soil layer in the 1956 revegetation area (Figure 5b),the 40-100 cm in the 1981 revegetation area (Figure 5d), the 40-60 cm soil layer in the 1991 revegetation area (Figure 5f), the 20-40 cm soil layer in the 2010 revegetation area (Figure 5h), and the 20-100 cm soil layer in the natural revegetation area(Figure 5j).

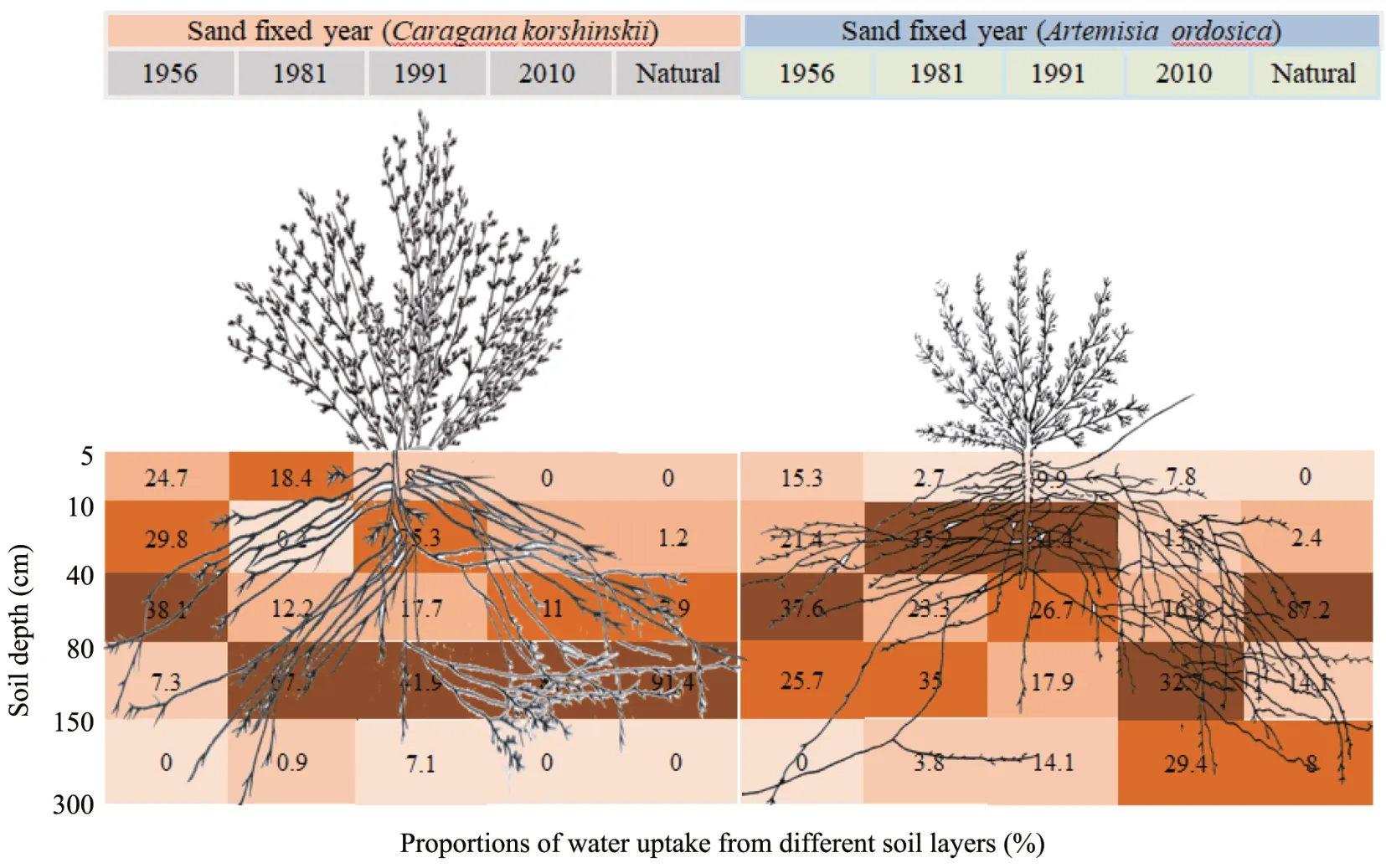

Based on the temporal and spatial distribution of soil moisture (Figure 3), the relative contribution of soil water was divided into five layers (Figure 6).The contribution of each layer of soil water to plant use changed over the year and the contribution rate of different soil layers was different for each plant species. ForCaragana korshinskii, 92.6% of water came from the 5-80 cm soil layer and nearly 40%from the 40-80 cm layer in the 1956 revegetation area. The water uptake proportions were 67.7%,41.9%,87.0%,and 91.4%in the 80-150 cm soil layer in 1981, 1991, and 2010 revegetation areas, and natural vegetation area respectively.

ForArtemisia ordosica,the main water uptake layer was also at the 40-80 cm layer in the 1956 revegetation area, with proportions of 37.6%, in the 1981 and 1991 revegetation areas.Artemisia ordosicamainly absorbed water from the 10-150 cm soil layer, and the contribution proportion was 93.5% and 76.0% respectively. The major water contribution soil layer was 80-150 cm (32.7%) and 40-80 cm (87.2%) in the 2010 revegetation and natural vegetation areas.

Figure 5 δ18O and δ2H in soil layers,xylem water,and underground water in different sites from the chronosequence of revegetation areas for Caragana korshinskii and Artemisia ordosica plants.XW and GW denote xylem water and underground water,respectively

Figure 6 The proportion of water uptake from different soil layers in different sand-fixed revegetation areas and different plant species.Square color represents the contribution rate,the darker the color,the higher the contribution rate

4 Discussions

In the process of artificial vegetation succession,the change of plant water absorption characteristics and the succession rule are the mechanism to maintain the stability of vegetation pattern,which is directly related to the formulation of ecological design and measures such as the species composition,community structure and functional community construction of artificial vegetation system. The sampling depth of the soil layers depends on the ecosystem type. Studies of plant water uptake using stable isotopes have demonstrated that sampling soil depths were not >100 cm in forests, were between 100 cm and 200 cm in croplands, and reached 300 cm in deserts (Zhaoet al.,2018).This variation can be explained by the distribution of roots. In deserts, plants have long roots, and even a soil depth of 300 cm may not include the whole root system (Daiet al., 2015). Rooting depth determines the soil volume from which plants can potentially draw water (Zhanget al., 2001), and changes in rooting depth and density can alter access to various sub-surface water stores with differing connectivity to the surface water. The coarse roots ofCaragana korshinskiiandArtemisia ordosicaplants were concentrated in the upper 0.4 m and 0.2 m respectively,while the fine roots stretched downward more than 3 m to extract soil moisture from deep soil layers(Zhanget al., 2008a, 2009).Thus, the sampling depths used in this study were reasonable.

The slope of LMWL (7.83) was less than a slope of 8 (Figure 4), which was derived from the global meteoric water line (GMWL): δ2H = 8 × δ18O + 10(Craig, 1961).The lower slope and intercept indicated that the stable isotope during precipitation was affected by secondary evaporation and that there was a strong effect of local vapor evaporation.Isotope ratios from underground water and the average annual precipitation weighted by volume were similar and plotted on the local meteoric water line (LMWL), indicating that neither underground water nor precipitation was measurably altered by evaporation. In contrast,plant stem and soil water showed substantial deviation and most soil and plant water samples fell below the LMWL, indicating partial evaporation after precipitation. Furthermore, the isotope ratios of xylem water were similar to integrated values of the soil water isotope ratios. These findings suggest that, in this arid desert area, plants take up water from soil water pools that do not use underground water, and that underground water shows no evidence of evaporative enrichment. Although evaporation can account for the isotopic ratios falling to the right of the LMWL,evaporation cannot account for variation along the line,particularly the low isotope ratios found in soil water at depth, values that are lower than underground water and the annual average precipitation isotope ratio.

Contributions of different soil layers to water uptake forCaragana korshinskiiandArtemisia ordosicaplants changed over time (Figure 6). This change is associated with the vertical variation in soil water stable isotope distribution in the different revegetation ar-eas (Figure 5). Although different proportions of water uptake came from different soil layers in these areas,Caragana korshinskiiplants mainly absorbed soil water from the 40-150 cm soil layer, andArtemisia ordosicaplants predominately uses 10-150 cm soil layer water.

Further, the main soil layer of water use by revegetation plants became shallower over time, largely driven by variation in the vertical distribution of soil moisture content. According to 60 years of observations, the water content of the topsoil (0-40 cm) is closely related to rainfall, which changes little among revegetation areas because they all receive similar precipitation.However,the soil moisture of deeper layers decreased significantly in older vegetation areas (Liet al., 2004, 2007).The main soil water absorption layer ofArtemisia ordosicaplants was shallow compared toCaragana korshinskiiplants, and this is likely related to the root distribution of each species (Zhanget al.,2008a,2009).

The key goal for studying the water uptake of the main revegetation plant species in desert areas is to provide reasonable water management strategies, especially for vegetation planting schemes. Many problems have arisen after the establishment of large areas of artificial sand-binding vegetation in China (Caoet al., 2011; Liet al., 2014; Dinget al., 2015), and new desertification is appearing in previously revegetated desert regions (Wanget al., 2008; Liet al., 2014;Dinget al., 2015). Consequently, the sustainable planting of artificial vegetation is important. In our study, the main water uptake layers differed between plant species, suggesting they require different planting practices.

Although this study quantified the proportion of water uptake from different water sources in revegetation areas of different ages, other related processes should be a focus of future studies. Process-based modeling methods might be coupled with the stable isotope method to improve the temporal resolution of water uptake by sand-binding plants.

5 Conclusions

The stable isotopes δ18O and δ2H were used to quantify the water uptake of two dominant sand-binding shrubs,Artemisia ordosicaandCaragana korshinskii, in artificial revegetation areas of different age in Shapotou area, Northwest China. The main water uptake layer forArtemisia ordosicaandCaragana korshinskiiplants shifted from deeper to shallower soils with time since revegetation. The main water uptake layer forCaragana korshinskiiwas 40-150 cm,whileArtemisia ordosicamainly absorbed soil moisture in the 20-150 cm layer. Both the soil moisture content and the root distribution influence the main water uptake layer. These different water uptake patterns and response mechanisms provide more accurate and locally adapted information regarding the establishment of artificial desert vegetation and water management practices in arid ecosystems.

Acknowledgments:

This study was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences(XDA23060202), and the Chinese National Natural Sciences Foundation(Grant Nos.41530750,41771101).We would like to thank Pro. Simon Queenborough at Yale University for his assistance with English language editing of the manuscript.

Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions2020年5期

Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions2020年5期

- Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions的其它文章

- Variation characteristics and prediction of pollutant concentration during winter in Lanzhou New District,China

- Seedling germination technique of Carex brunnescens and its application in restoration of Maqu degraded alpine grasslands in northwestern China

- Calculation of salt-frost heave of sulfate saline soil due to long-term freeze-thaw cycles

- Processes of runoff in seasonally-frozen ground about a forested catchment of semiarid mountains

- Effect of debris on seasonal ice melt(2016-2018)on Ponkar Glacier,Manang,Nepal

- Editors-in-Chief Yuanming Lai and Ximing Cai