Effect of debris on seasonal ice melt(2016-2018)on Ponkar Glacier,Manang,Nepal

Reeju Shrestha,Rijan B.Kayastha,Rakesh Kayastha

Himalayan Cryosphere, Climate and Disaster Research Center (HiCCDRC), Department of Environmental Science and Engineering,School of Science,Kathmandu University,Dhulikhel 45200,Nepal

ABSTRACT Supraglacial debris is widely present on glaciers in alpine environments and its distribution greatly affects glacier melt.The present study aims to determine the effect of debris on glacier ice melt on Ponkar Glacier,Manang District,Nepal.We estimated ice melt under various debris thickness using Energy Balance (EB) model and conductive heat flux methods,which are compared with in-situ observations. Four stakes are installed on the glacier at different debris thickness of 11-40 cm. Meteorological data from March 2016 to May 2018 are obtained from the Automatic Weather Station (AWS)installed on the glacier surface at an elevation of 3,881 m a.s.l.for the energy balance calculation.Debris surface temperature and different debris depths are also measured on the glacier. The calculated ablation rates from the conductive heat flux method are 0.9, 1.62 and 0.41 cm/d on pre-monsoon, monsoon and post-monsoon, respectively, with mean debris thermal conductivity 1.04 W/(m?K).The net radiation shows little variation between the seasons,while turbulent heat flux varies in the season.Sensible heat flux was found to be highest in post-monsoon season due to a larger temperature gradient between surface and air.

Keywords:debris-covered glacier;thermal conductivity;energy flux;Ponkar Glacier;ice melt;Hindu-Kush Himalaya

1 Introduction

Debris-covered glaciers are a prominent feature of alpine mountain ranges with particularly large concentrations found in mountains which are still uplifting,like the Himalaya, Alaska or the Andes (?strem,1959; Kirkbride, 2011). The ablation zones of such glaciers are wrapped in near-continuous layer of rock debris, which have a very significant impact on glacier mass balance through its influence of surface melt (Bozhinskiyet al., 1986). The enhancing and retarding of the melt rate under the debris layer varies under the influence of meteorological parameters as well as debris lithology such as debris thickness, thermal conductivity and albedo (Loomis, 1970; Fujii,1977; Moribayashi and Higuchi, 1977; Adhikaryetal.,2000;Shahiet al.,2015).

Thin layers of debris enhance ice melt through surface albedo reduction, whereas a thick debris acts like a blanket and insulates the ice from atmospheric heat and insolation (?strem, 1959; Mattsonet al., 1993;Adhikaryet al., 2000; Mihalceaet al., 2006; Brocket al.,2010;Reidet al.,2012).This barrier to heat transfer causes less ice melt once a critical thickness is exceeded (Mihalceaet al., 2006; Ragettliet al., 2013;Fyffeet al., 2014). The degree to which debris alters ablation is difficult to quantify under real conditions.This is due to the typical highly heterogeneous nature of supraglacial debris cover on glaciers, local climatic conditions and lithology (Scherleret al., 2011; K??bet al.,2012).

A number of recent studies have documented the effect of debris on glacier melt using surface energy balance models with surface temperature and meteorological variables (Greuell and Smeets, 2001; Reid and Brock, 2010; Fyffeet al., 2014; Chandet al.,2015). However, little is known about the proper understanding processes beneath highly heterogeneous debris cover (composition, thickness distribution and moisture content), as in Nepalese Himalayas. There are 256 debris-covered glaciers with a total area of 445.7 km2out of 3,808 glaciers in Nepal (Bajracharyaet al.,2014).Thus,there is a need for study physically based ablation models for debris-covered glaciers that can be used to predict melt rate in response to meteorological conditions. Empirical degree-day approaches are normally used (Glazyrin, 1975; Kayasthaet al., 2000; Singhet al., 2000; Mihalceaet al.,2006;Hagget al.,2008),owing to limited data availability in remote mountain locations and poor knowledge of key processes. On Miage Glacier, Italy, the mean ablation rate was found to be 0.6-3.3 cm/d using an energy balance model (Brocket al., 2010).Similarly, the ablation rate under 0.01 m debris thickness was reported to be the highest(6 cm/d)(Mihalceaet al., 2006). At Tasman Glacier, there was a clear contrast between ablation rates on clean ice surfaces compared with debris-covered ice, which reported clear evidence that ablation rates under debris thickness were suppressed by up to 93% in 1.1 m debris thickness (Purdie and Fitzharris, 1999). On Khumbu Glacier, researchers reported melt rates of 4.7, 2 and 1.2 cm/d from debris covers of varying thicknesses of 2,10 and 30 cm,with enhancement of melt rate under thin debris cover(Kayasthaet al.,2000).Using an energy balance model, rate of ice melt was observed to be 2.4 cm/d in monsoon season in Lirung Glacier(Shahiet al., 2015). On the same glacier, authors calculated the highest ablation rate of ice (3.52 cm/d) in monsoon season, 2013 (Chandet al., 2015). In summary, significant difference in debris-covered glaciers are observed in melt rate as compared to clean glaciers.

Supraglacial debris plays an important role in glacier dynamics. Recent studies suggests that morphological factors such as surface gradient is the main controlling factor on glacier response to climate(Salernoet al.,2017).Debris thickness or coverage also effects the formation and evolution of ice cliffs,but lacks significance on the formation of supraglacial ponds (Watsonet al., 2017). Debris properties such as thermal conductivity, albedo and surface roughness are governing variables on debris energy balance studies (Rounceet al., 2015). The aforementioned factors are all crucially important in understanding the nature of ice melt in debris-covered glaciers,however,only a few factors along with their effects are considered in this research. In this paper, a physically based energy balance model and conductive heat flux methods are used to calculate ice melt under different debris layers of Ponkar Glacier in Nepal Himalaya. The results are then compared with measured data in the field at different seasons to elucidate which method is better suited for ice melt estimation under a debris layer.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Description of study site

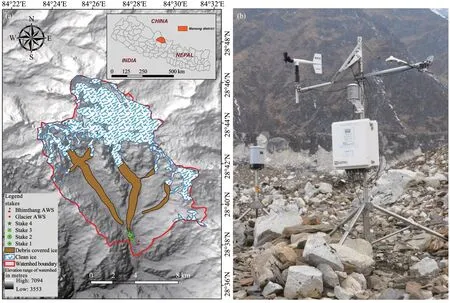

This study was conducted on Ponkar Glacier(28.63°N,84.47°E)which lies in Ponkar catchment of Bhimthang Valley (Figure 1a). Ponkar Glacier lies in the headwaters of Dudh Khola and has an area of 30.21 km2,out of which 25.6 km2is clean ice and 4.61 km2is the debris-covered ablation area with an altitude ranging from 3,555 to 7,108 m a.s.l.. The Advance Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER) Global Digital Elevation Model Version 2 of 30 meters spatial resolution available from USGS (GDEM_ASTER, 2000) is used for the elevation information. The accumulation area of the glacier extends from Himlung peak in the north-west to Panbari Himal in the north-east.The estimated average thickness of the glacier is 134.05 m (Bajracharyaet al., 2014). This study is focused on the lower ablation part of the glacier. Automatic Weather Station at an elevation of 3,881 m a.s.l. on the glacier surface is installed for meteorological measurements(Figure 1b).

Four ablation stakes were mounted at equal altitude difference of 50 m in lower part of Ponkar Glacier to estimate ice melt and down-wasting(Figure 1).

Three sets of smart buttons are equipped within the debris layer near AWS site, to measure temperature profiles through the debris layer.

2.2 Ablation from stake measurements

Debris-covered ice is hand-drilled up to 2.5 m using an ice auger through the debris thickness of 11 to 40 cm in order to mount the ablation stakes. The disturbance in the debris during the process is minimised as much as possible. To determine the effect of varying supraglacial debris thicknesses on ice melt, ablation is measured using these stakes from 2016 to 2018 spanning three seasons.

2.3 Energy balance model

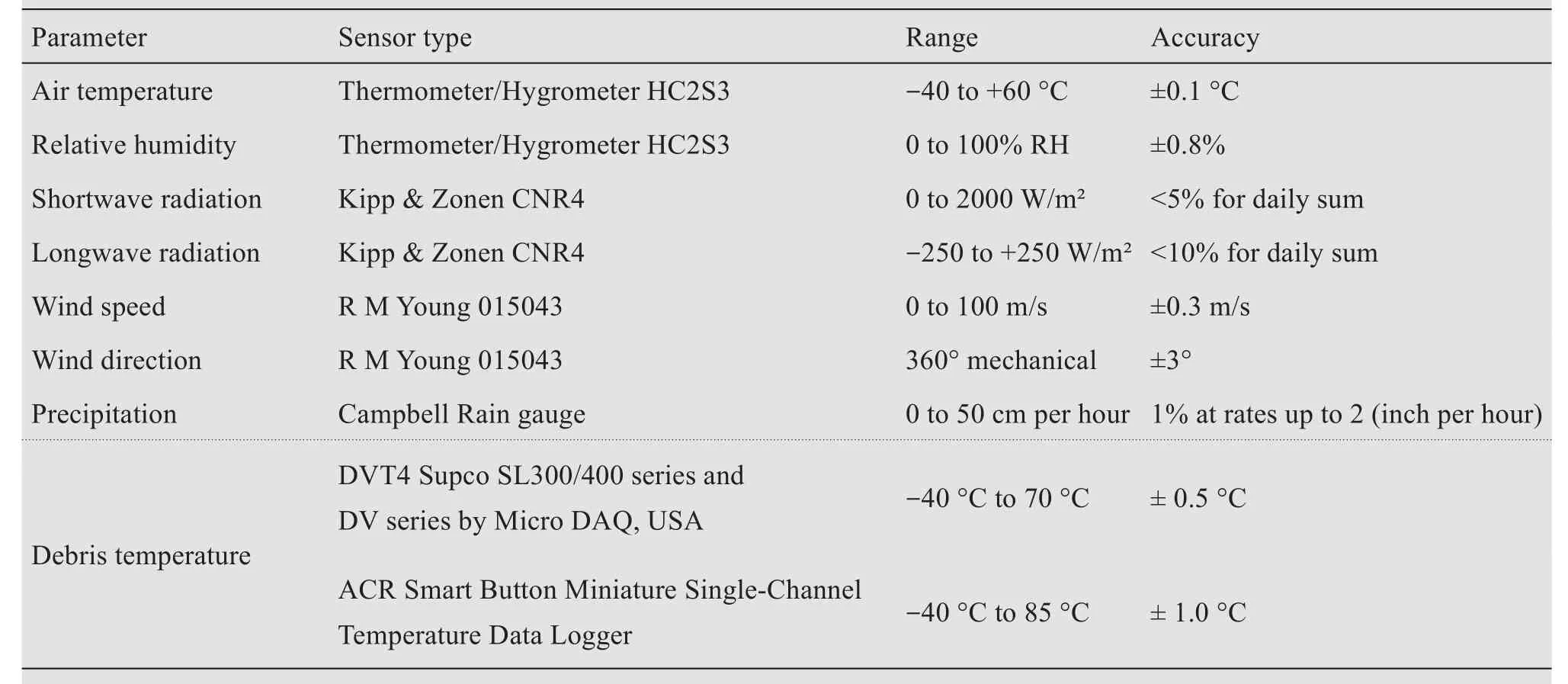

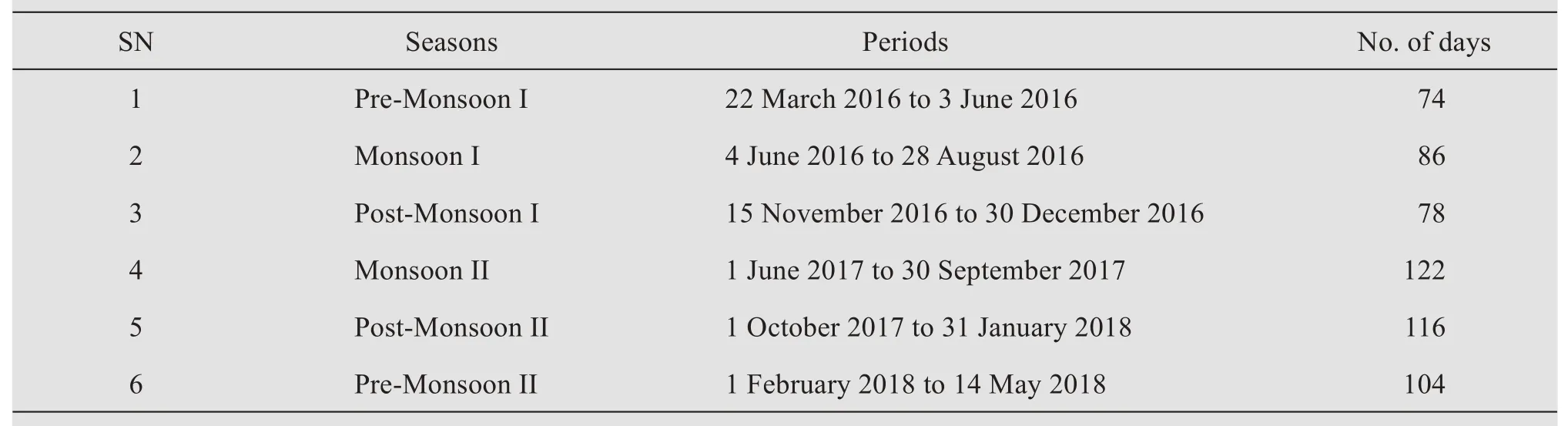

Energy balance models have been developed for both debris-covered glaciers (Nakawo and Young,1981; Nicholson and Benn, 2006) and clean glaciers(Kayasthaet al., 1999; Brock and Arnold, 2000; Oerlemans and Klok, 2002; Pellicciottiet al., 2008). The model used in this study is driven by meteorological variables. The meteorological measurements are conducted on the debris-covered ablation zone of Ponkar Glacier at the AWS site. All the sensors were leveled to record fluxes perpendicular to the surface at 2 m above the debris surface (Table 1). The meteorological data are collected from 2016 to 2018 spanning three seasons(Table 2).

Figure 1 (a)Location map of study area,Ponkar Glacier in Manang District,Nepal,with the location of AWS and stakes.(b)Photo of AWS installed in ablation part of Ponkar Glacier

Table 1 Specifications of instruments installed on Ponkar Glacier

Table 2 A list of seasons and periods of data used in this study

The energy balance equation on a bare ice surface is given by(Kayasthaet al.,2000):

The energy balance equation on top of a debris layer is determined by the sum of fluxes at the atmosphere/glacier boundary and is given by (Kayasthaet al.,2000;Chandet al.,2015):

whereQM,QC,QR,QHandQEare total energy available for melt, conductive heat flux through the debris,net radiation flux, sensible heat flux and latent heat flux, respectively. The heat contributed by precipitation is neglected in both cases. This model assumes that all fluxes on top of the debris transfers to the debris/ice interface.Also,fluxes that are towards the surface are taken as positive and are in units of W/m2.

2.3.1 Radiative fluxes

The net radiation flux (QR) at the AWS site is calculated by sum of net shortwave (Snet) and net longwave(Lnet)fluxes and is given by:

SnetandLnetis measured by a Kipp&Zonen CNR4 sensor.

2.3.2 Turbulent heat fluxes

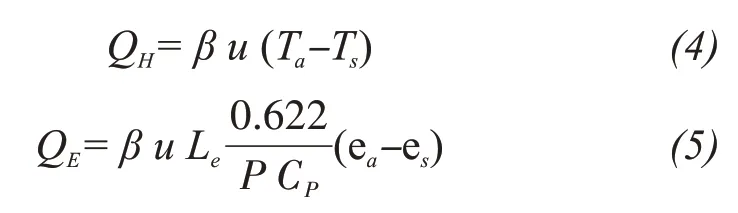

The turbulent heat fluxesQHandQEare estimated using the bulk aerodynamic method:

whereβis bulk transfer coefficient(4.9 J/(m3?K));uis wind speed (m/s);Leis latent heat of evaporation(2.5×106J/kg);Pis atmospheric pressure (hPa);CPis specific heat of air at constant pressure(1,005 J/(kg?°C));eais vapor pressure of the air (hPa);esis the saturation vapor pressure at the surface(hPa).

2.4 Conductive heat flux method

This approach assumes that the only heat flux considered to reach the glacier ice is conductive flux and it assumes that there is no further downward conduction of heat(Reid and Brock,2010).It depends on the temperature gradient at the base of the debris. Three smart buttons are used to measure debris temperature at the surface P1(0 cm),15 cm down from the surface at P2(15 cm)and 30 cm down at P3.Thin debris cover(almost 0.3 cm) was spread on top of the thermistor which was installed on the debris surface to shield from direct solar radiation effect.Additionally, Supco thermisters are installed near stake 2 on 10 December 2017.Supco thermistor data is used to fill out the data gap from the smart button (February 11 to March 4,2018).

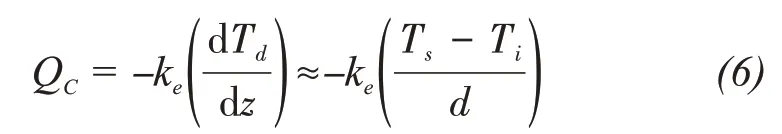

The conductive heat flux,QC, at the debris surface is calculated from the Fourier heat conduction equation (Conway and Rasmussen, 2000), based on the temperature gradient at the top of the debris layer and at the debris/ice interface:

wherekeis thermal conductivity of the debris (W/m2),Tdis temperature inside the debris surface (°C),zis depth below the surface,Tsis surface temperature,Tiis temperature of the ice/debris interface(°C), anddis thickness of debris layer (m) assuming all heat is transferred from surface to the debris-ice interface.

2.4.1 Thermal diffusivity and thermal conductivity

The thermal conductivity of the debriske(W/(m?K))is calculated using the method of Conway and Rasmussen (2000). This method assumes all heat flux to occur by conduction, and thermal conductivity to be constant with depth.Thermal diffusivity of the debris is calculated using a one-dimensional thermal diffusion equation:

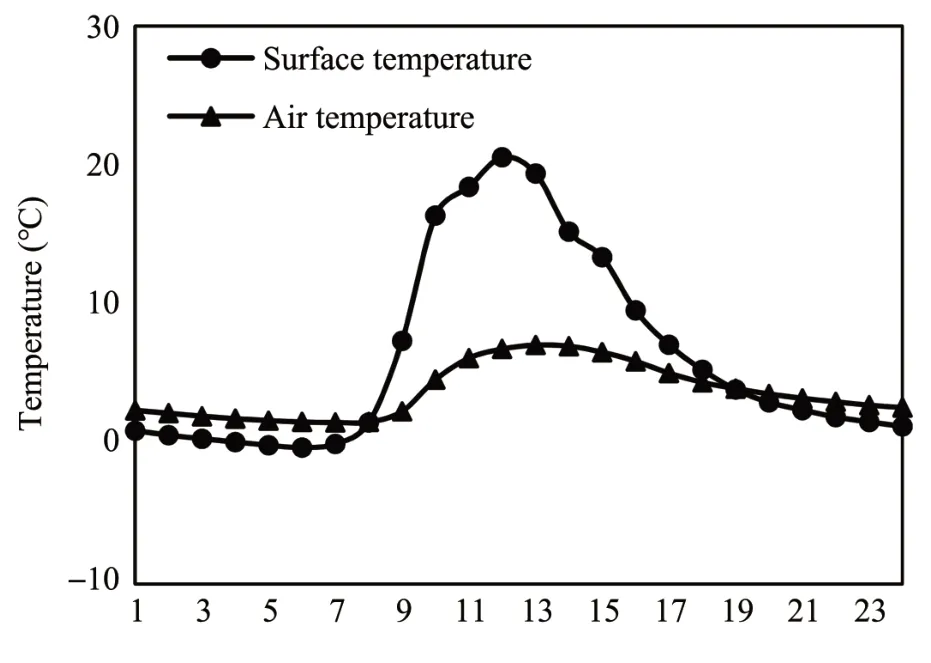

whereTis debris temperature,tis time andzis the vertical coordinate. A value ofαat each thermistor depth can be determined as the gradient of the best-fit line of the first derivative of temperature with time plotted against the second derivative of the temperature with depth. Then kecan be determined from the equation:

wherecis specific heat capacity (750 J/(kg?K)),ρis bulk density(2,700 kg/m3)andαis thermal diffusivity(m2/s)of the debris(Conway and Rasmussen,2000).

2.5 Ablation rate

The ablation rate (r) from energy balance method is calculated as:

The ablation rate (r') from conductive heat flux method is calculated as:

whereLfis latent heat of fusion of ice (334×103J/kg),ρiis density of ice(900 kg/m3)andris ablation rate of ice in specific debris thickness (m/s) (Chandet al.,2015). If the calculated melt rate is negative (due to negative temperatures in the debris layer above), it is set to zero.

3 Results

3.1 Meteorological components

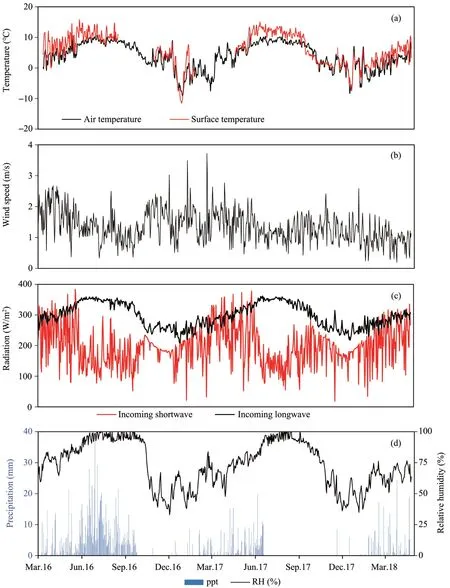

Meteorological records of each season are analyzed separately to know the variation over those seasons. There is a key difference between meteorological conditions during pre-monsoon, monsoon and post-monsoon seasons which result in different patterns of melting. Over the period of record the mean daily maximum air temperature is 11.39 °C observed during monsoon season and mean daily minimum air temperature is -9.08 °C observed during post-monsoon period.

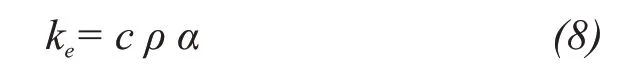

The behavior of air and surface temperatures during day and night is displayed in Figure 2. In daytime, air temperature over a debris-covered glacier is due to the heating of debris layer. During the night, the surface temperature is notably lower than air temperature but as the morning commences, surface temperature starts to increase and eventually reaches above the air temperature and drops down again in the evening.This is due to the fact that the debris stores heat during the day time and release it slowly during the cold night time.

Figure 2 Mean hourly variation of air and surface temperatures at AWS averaged over the entire period of record

Figure 3a shows the hourly variation of air and surface temperatures over the entire measurement period (surface temperature data is missing from August 28 to November 15 2016, and January 1 to May 31 2018, due to sensor failure). It can be distinctly seen that surface temperature is consistently higher than that of the air temperature. However, the surface temperature has much large diurnal oscillation.

Observed daily mean maximum wind speed are highest (3.49 m/s) in Post-Monsoon I and daily mean minimum (0.19 m/s) in pre-monsoon season (Figure 3a).The valley wind increases in the daytime as a consequence of an increased glacier wind due to a stronger temperature deficit between the atmosphere and the glacier surface in the afternoon. Conversely, the katabatic or glacier wind starts to develop only during the night time. This is due to increase in temperature difference during the night time when the heat stored by the debris during day time is released to the atmosphere which warms the air temperature. The katabatic wind during post-monsoon season is weak.Katabatic force is created by the temperature contrast between the melting glacier surface and the ambient atmosphere. This is why katabatic winds are normally observed highest during monsoon season of maximum air temperature.

The mean incoming solar radiation is highest in pre-monsoon season (383.90 W/m2) and lowest in winter season (166.99 W/m2).However,the mean daily maximum value is highest in monsoon season than in dry seasons. The lower mean value is due to cloud cover and fog in monsoon season. The lower value of radiation in post-monsoon is due to the tilting of the earth. The maximum and mean value of incoming solar radiation is consistent every day during this season(Figure 3c). This evenness is due to general climate variability in the high mountains by cloud formation and precipitation events. However, in case of monsoon and pre-monsoon seasons, radiation is more fluctuating due to the fact that in monsoon season,there is more cloud cover. The mean daily incoming solar radiation for the period is 193.23 W/m2. Conversely, mean daily down-welling longwave radiation of two monsoon periods is 343.70 W/m2. Incoming longwave radiation decreases in post-monsoon and minimum mean daily incoming longwave in pre-monsoon season(290.18 W/m2).

Figure 3 Mean daily variations of meteorological parameters at the AWS on Ponkar Glacier(a)Air and surface temperatures(°C),(b)Wind speed(m/s),(c)Incoming shortwave and longwave and(d)Relative humidity(%)and precipitation(mm)

Figure 3d shows the average daily precipitation variation during the study period. The highest total precipitation is recorded in Monsoon I season(878.08 mm), followed by pre-monsoon (187.47 mm)and lowest in post-monsoon (57.66 mm). No precipitation is recorded from July to December 2017 due to tilted rain gauge on the debris surface by underlying ice melt.The mean relative humidity is found higher in monsoon season than the winter and pre-monsoon seasons.Mean humidity is 71%, 93% and 63% during pre-monsoon,monsoon and post-monsoon seasons,respectively.

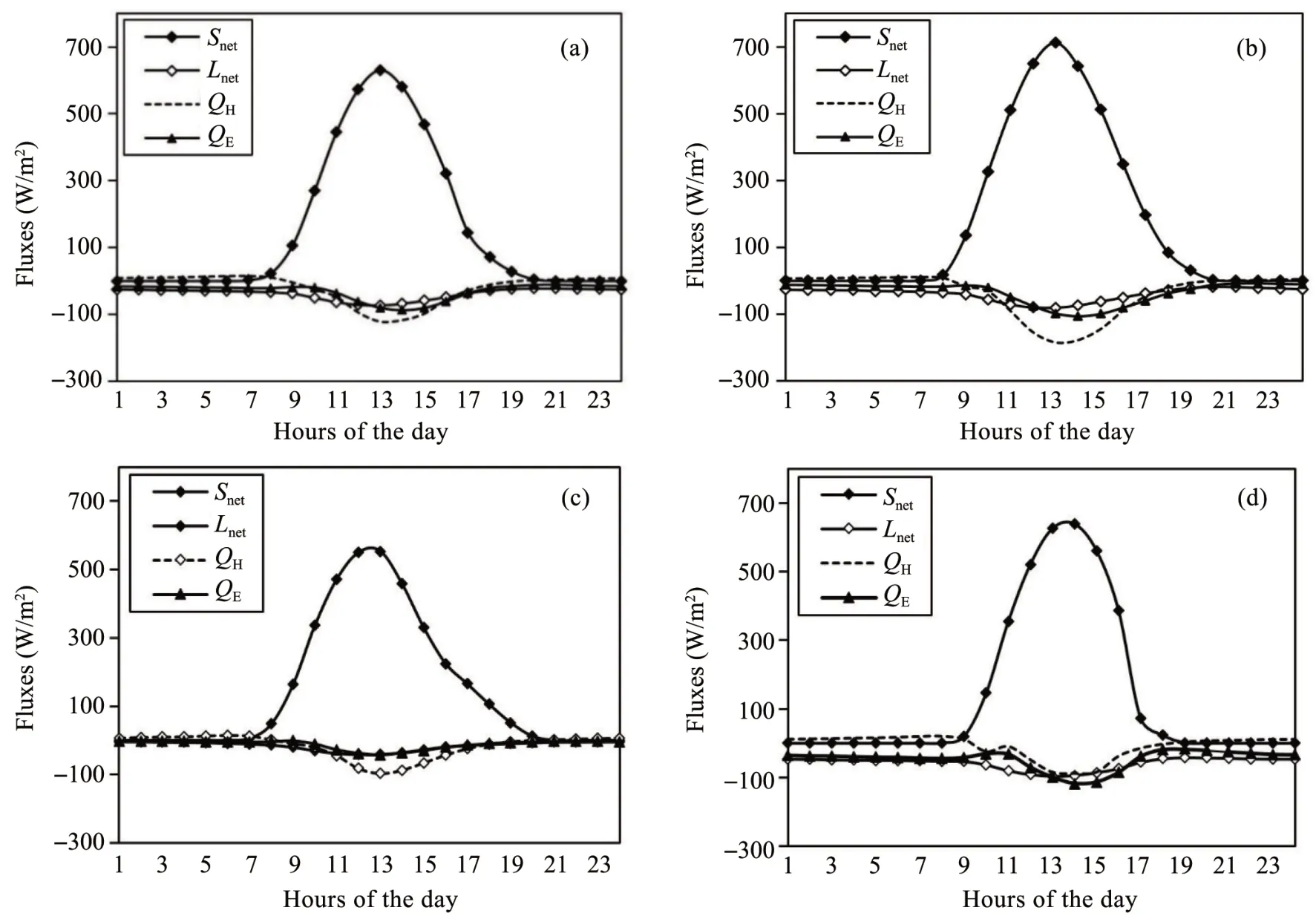

3.2 Energy balance calculation

Diurnal variations of energy balance components on Ponkar Glacier in three different seasons are calculated and presented in Figure 4.The net shortwave radiation (Rnet) is the main dominant source of heat for melt during the day time followed by net longwave radiation(Lnet),and other fluxes act as a sink.Incident solar radiation in Lirung Glacier and Rakhiot Glacier is also the dominant contribution of energy to surface melt (Mattsonet al., 1993; Chandet al., 2015). Sensible heat flux (QH) is found to be comparatively higher in post-monsoon season than other seasons due to moderate wind speed and higher air temperature. Latent heat flux (QE) is found to be comparatively similar in pre-monsoon and in post monsoon, and is found to be high in monsoon season owing to the relatively large amount of cloud cover and lower surface temperature.

Figure 4 Mean daily cycle of calculated surface heat fluxes for(a)entire period,(b)pre-monsoon,(c)monsoon and(d)post-monsoon at AWS site.Mean daily cycles of heat fluxes are calculated from hourly heat flux during the study period

3.2.1 Ice melt from EB calculation

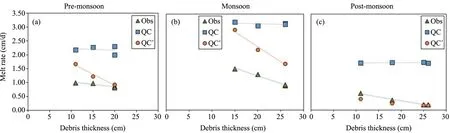

The ice melt rate is estimated from the available flux needed for ice melt (QC). The calculated mean daily melt rates are 2.18, 3.16, 1.72 cm/d in pre-monsoon,monsoon and post-monsoon,respectively.

3.3 Results from conductive heat flux method

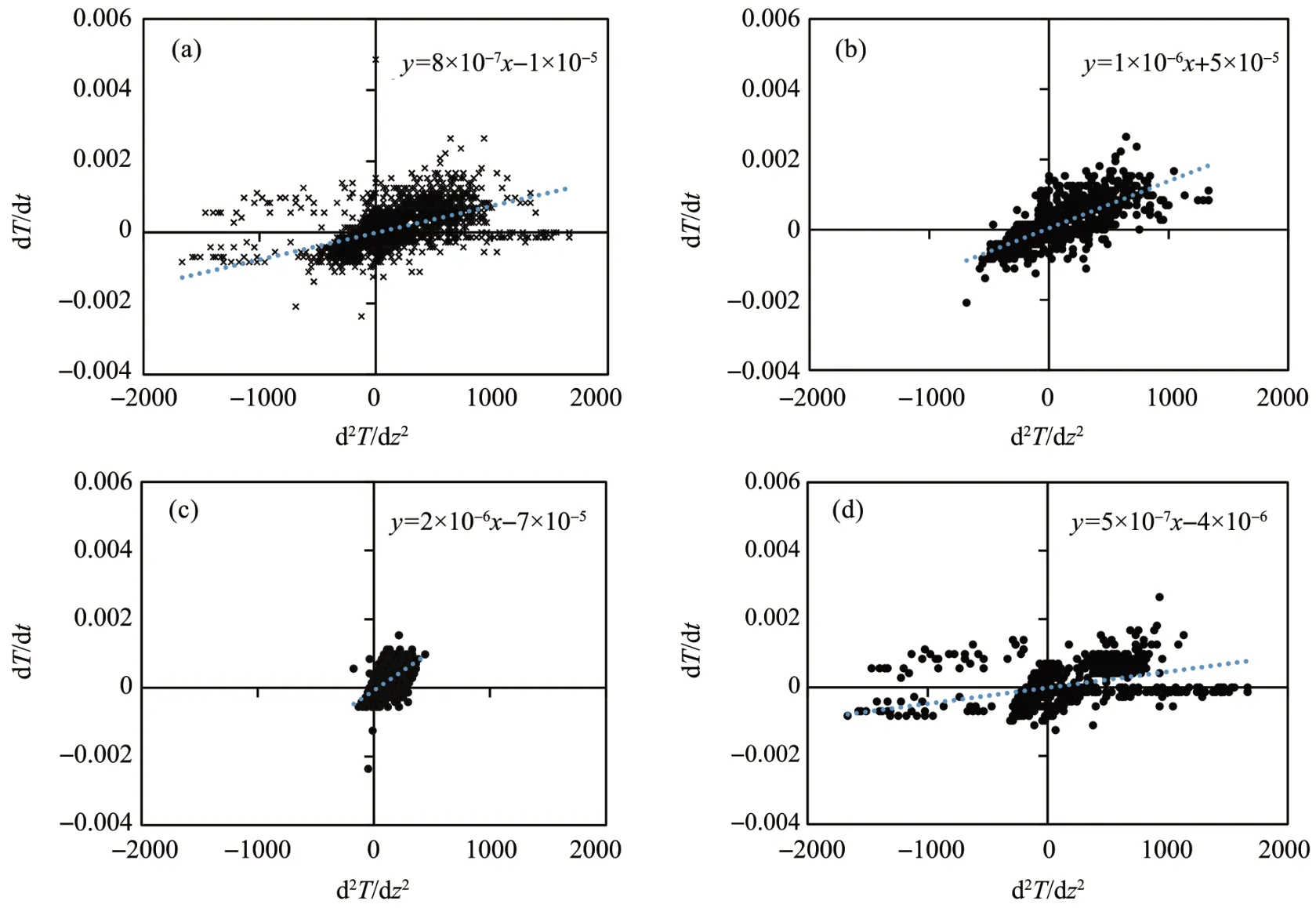

3.3.1 Thermal conductivity

For the estimation of thermal conductivity, the first derivative of temperature with time against the second derivative of temperature with depth at 30 cm for entire period, pre-monsoon, monsoon and postmonsoon seasons is plotted. The slope of the best linear fit gives an approximation of the mean diffusivity at a particular debris thickness (Figure 5). Then the thermal conductivity is calculated using Equation(8)and the values are 0.92,1.75 and 0.45 W/(m?K)in premonsoon,monsoon and post-monsoon,respectively.

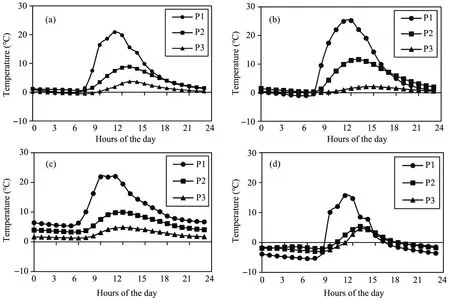

3.3.2 Debris temperature profile

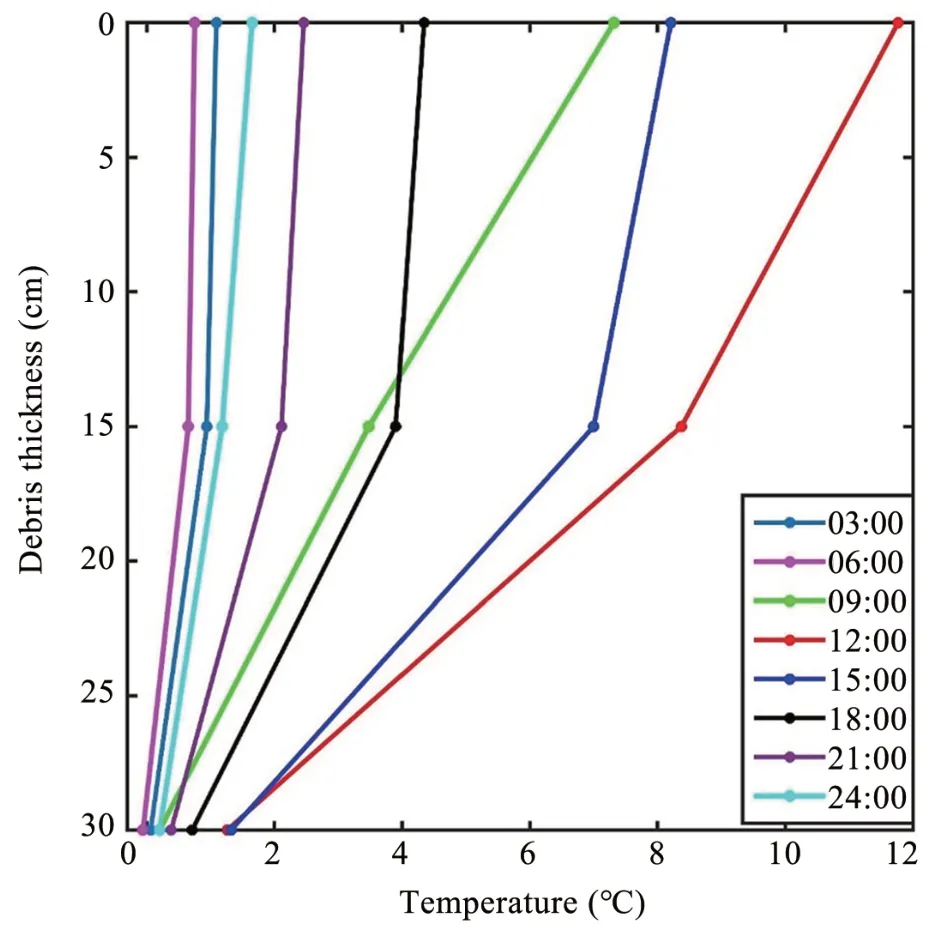

The debris temperature was measured at the surface, 15 cm down from the surface and 30 cm down from the surface. Debris temperature decreases remarkably from the surface downwards in pre-mon-soon season (Figure 6). During pre-monsoon season, the highest temperature was found at 12 noon at the surface, 13:00 at 15 cm from the surface and 15:00 at 30 cm from the surface, which suggest time lag of temperature as it moves through the debris surface.

Figure 5 Scatter plots of the first derivative of temperature with time against the second derivative of temperature with depth at 30 cm for(a)entire period,(b)pre-monsoon,(c)monsoon and(d)post-monsoon

Figure 6 Daily debris temperature on Ponkar Glacier at different depths of the debris layer measured from the surface for(a)All seasons,(b)Pre-monsoon,(c)Monsoon and(d)Post-monsoon seasons.Lines with circles are for 0 cm,squares are for 15 cm and with triangles are for 30 cm from the debris surface at AWS site

Vertical temperature gradients are calculated based on measured temperatures at different debris thickness during the entire period.The diurnal temperature is typically not linear profiles (Figure 7). The highest difference of temperature between surface and various depths is found at 12 noon and it is lowest at 06:00 a.m..At debris surface, the temperature during 12 noon is 11.77 °C and at 15 cm from surface is 8.37 °C and at 30 cm debris thickness is 1.26 °C.The temperature decreases from surface to 30 cm down with a rate of 0.35 °C/cm. This shows that temperature is reduced by 25%in 15 cm and by 90%in 30 cm debris thickness from the surface.

3.3.3 Ice melt from conductive heat flux method

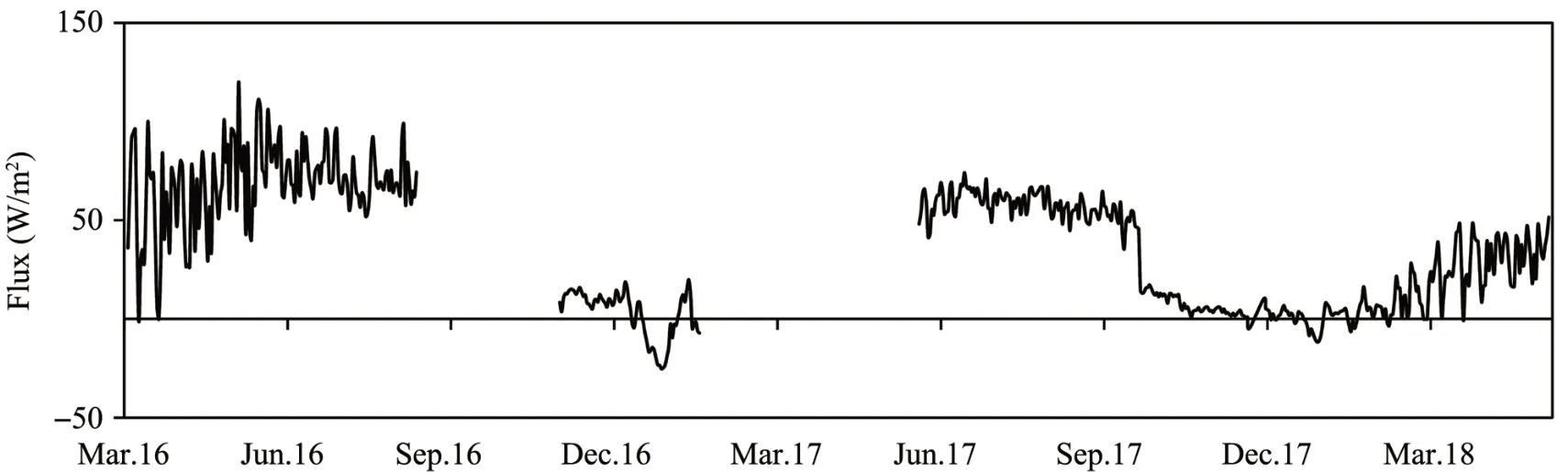

The conductive heat flux calculated from debris temperature and depth is plotted in Figure 8. Conductive heat flux was found to be largest in the warmest and sunniest period when the debris surface temperature was highest.QC'shows little variation between the seasons despite the contrasting meteorological conditions. The calculated and observed variations of mean ice ablation rate during an observation period of pre-monsoon, monsoon and post monsoon seasons at dirty ice and under different debris thicknesses is illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 7 Distribution of average hourly debris temperature from 0 to 30 cm debris thicknesses

Figure 8 Calculated conductive heat flux during the study period.Discontinuity of data is due to missing surface temperature data

Figure 9 Comparison of observed melt rates(triangles)with calculated daily ice ablation from energy balance model(squares)and calculated daily ice ablation from conductive heat flux method(circles)in(a)Pre-monsoon,(b)Monsoon and(c)Post-monsoon seasons

4 Discussions

Figure 9 shows the daily ice ablation for the three seasons of period I at different stakes using EB model and conductive heat flux method, and compared with observed data.The energy balance model overestimated the melt up to two times, which shows that the assumption; all energy fluxes on the debris surface is transferred to the debris/ice interface and used for melting ice, is not suitable in this case. Some heat flux may dissipate horizontally and also transfers from the debris layers which is similar to temperature reduction from surface to 30 cm below surface. The vertical temperature profile shows that the surface temperature decreases by about 25% from surface to 15 cm below surface and 90% from surface to 30 cm below the surface. Assuming the reduction of heat flux similar to that of temperature from surface to 15 and 30 cm below surface, the resulting ice melts from EB model will be close to the measured one or similar to the one calculated from the conductive heat flux.In contrast, results from the observation and conductive heat flux method matches to some extent in pre-monsoon and post-monsoon seasons beneath debris of 20 and 25 cm thick. However, the overestimation of ice melt is the highest in monsoon season from both methods. Again, comparing ice melt by these two methods, the heat conduction method is near to observed ice melt. Thus, the conductive heat flux method simulates well compared to the EB model.The limitation of this model is that it only accounts thermal conductivity as flux calculation. Whereas, properties of the debris required in debris energy balance models are albedo, thermal conductivity, and surface roughness (Rounceet al., 2015). This study only considers the lower part of the debris region of the glacier as the surface morphological feature is harsh on the upper part, and due to inaccessibility which limits the study to cover the entire debris-covered area. The debris thickness at the stakes changed between the seasons due to nearby debris accumulation in depressions caused by the underlying ice melt. Observation and model results indicates that melt beneath debris layer more than 15 cm is most pronounced in pre-monsoon and post-monsoon seasons. During pre-monsoon season, the highest temperature is found at 12:00 at the surface, 13:00 at 15 cm below the surface and 15:00 at 30 cm below the surface.The time lag for the maximum temperature at 30 cm below debris surface is found to be three hours during pre-monsoon and two hours during post-monsoon.

5 Conclusions

This study implemented EB model and conductive heat flux method to estimate the melt rate in a debris-covered glacier. Thermal diffusivity and thermal conductivities are important characteristics of debris material which contributes to ice melt beneath the debris cover. The thermal conductivity of the supraglacial debris of Ponkar Glacier was found to be of large differences between the seasons with an average of 1.75 W/(m?K) in monsoon period. The melt rates are 0.9, 1.62, 0.41 cm/d in pre-monsoon, monsoon and post monsoon seasons,respectively,from conductive heat flux method. The information acquired from this research can be useful in ice melt calculations from debris-covered glaciers which will be useful for knowing water availability and distribution in the downstream region. In future, in order to significantly apply these models in estimating melt in debris-covered glaciers, spatial and temporal observed data should be enhanced. Also, more measurements should be done in a debris-covered glacier with thickness less than 10 cm to know the effective debris thickness.

Acknowledgments:

The HKH Cryosphere Monitoring Project implemented by the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) and supported by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Contribution to High Asia Runoff from Ice and Snow (CHARIS) funded by United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through the University of Colorado at Boulder, CO, USA. We would like to express thanks to Fan Zhang, ITP, CAS, Beijing, China for her support to install an AWS at Bhimthang,Manang. Also we would like to thanks Mohan B.Chand and Tenzing C. Sherpa for their assistance in field data collection and analysis.

Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions2020年5期

Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions2020年5期

- Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions的其它文章

- Variation characteristics and prediction of pollutant concentration during winter in Lanzhou New District,China

- Variation in water source of sand-binding vegetation across a chronosequence of artificial desert revegetation in Northwest China

- Seedling germination technique of Carex brunnescens and its application in restoration of Maqu degraded alpine grasslands in northwestern China

- Calculation of salt-frost heave of sulfate saline soil due to long-term freeze-thaw cycles

- Processes of runoff in seasonally-frozen ground about a forested catchment of semiarid mountains

- Editors-in-Chief Yuanming Lai and Ximing Cai