Seedling germination technique of Carex brunnescens and its application in restoration of Maqu degraded alpine grasslands in northwestern China

JianJun Kang,WenZhi Zhao*,CaiXia Zhang,Chan Liu,ZhiWei Wang,HaiJun Wang

1. Linze Inland River Basin Research Station, Key Laboratory of Inland River Basin Ecohydrology, Northwest Institute of Eco-Environment and Resources,Chinese Academy of Science,Lanzhou,Gansu 730000,China

2.Guizhou Institute of Prataculture,Guizhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences,Guiyang,Guizhou 550006,China

3.Zhangye Academy of Agricultural Sciences,Zhangye,Gansu 734000,China

ABSTRACT Carex brunnescens (Pers.) Poir. is considered to be the only clonal herb found to date that can develop and form fixed dunes in Maqu alpine degraded grasslands of northwestern China. However, due to strong dormant characteristics of C.brunnescens seeds, the sand-fixing effect of the plant is severely limited.This study explores a technique that can rapidly promote the seed germination of C.brunnescens,and also investigates the adaptation and sand-fixing effect by cultivating C. brunnescens seedlings to establish living sand barriers in the sand ridges of moving sand dunes. Results show that the seed germination rate obtained a maximum of 63.7% or 65.1% when seeds were treated with 150 mg/L gibberellic acid(GA3)for 24 h followed by soaking in sulfuric acid(98%H2SO4)for 2.5 min or sodium hydroxide(10%NaOH)for 3.5 h,and then germinated (25 °C in daytime and 5 °C at nighttime) in darkness for 10 d.After breaking seed dormancy of C.brunnescens,the living sand barrier of C.brunnescens(plant spacing 15-20 cm;sand barrier spacing 10-20 m)was established in the perpendicular direction to the main wind in the middle and lower parts of the sand ridges on both sides of the moving sand dunes.When the sand ridges were leveled by wind erosion,the living sand barrier(plant spacing 15-20 cm;sand barrier spacing 0.5-1.0 m) of C. brunnescens was reestablished on the wind-eroded flat ground. Finally, a stable sand-fixing surface can be formed after connecting the living sand barriers on both sides, thus achieving a good sand-fixing effect. These findings suggest that rapid seed germination technology combined with the sand-fixing method of C. brunnescens can shorten the seed germination period and make the seedling establishment become much easier which may be an effective strategy to restore and reconstruct Maqu degraded grasslands.

Keywords: Carex brunnescens; living sand barrier; Maqu degraded grasslands; moving sand ridge; sand-fixing method;seed germination technique

1 Introduction

Desertification is one of the most serious abiotic stresses faced by mankind at present. It unavoidably results in serious effects to the sustainable development of agriculture and eco-environmental construction globally due to a rapid decrease of vegetation coverage and a continuous runoff of soil nutrients and stability by destroying the nutrient-rich surface soil(Chenet al., 2020). According to data issued by the United Nations, desertification has affected 1/5 of population and 2/3 of countries in the world(Suet al.,2007; Liuet al., 2013). China is one of the countries suffering from the most serious desertification in the world, especially the increasing aridity and desertification of the grassland in northwestern China, which has led to serious eco-environmental problems(Santiagoet al.,2016;Ninget al.,2020).

The source region of the Yellow River (Maqu) is one of the most important alpine meadows on the eastern edge of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau in Northwest China. This area is known as "the kidney of the Yellow River" and is embraced by the Yellow River in the east, south and north to form the first bend of the Yellow River (Wanget al., 2019a). Its unique geographical environment is an important ecological barrier and plays very important role in maintaining water resources and ecological security in the upper reaches of the Yellow River Basin (Yueet al., 2018; Wanget al., 2019b). However, under the background of global climate change, the eco-environment in Maqu alpine grassland has tended to deteriorate seriously due to the increasingly frequent man-made interference and damage (Wanget al., 2015; Huet al., 2017; Zouet al., 2019). In recent years, the Ministry of Science and Technology of China and Gansu Province in Northwest China have set up multiple projects to control desertification in Maqu (Zouet al., 2019; Ninget al., 2020). However, due to insufficient understanding of the particularity of alpine grassland environment,the control measures are the conventional desertification control methods based on the introduction and domestication of sandy plants, and the combination of shrubs and grasses with engineering measures, which lead to high cost, poor adaptability, and unsatisfactory effects of desertification control (Kanget al., 2015,Jinget al.,2016;Kanget al.,2017a).In order to solve these problems, it is urgent to find new ways to control desertification in Maqu alpine areas.

Carex brunnescens(Cyperaceae), a perennial herb native to the Maqu desertified alpine areas, is one of the dominant and constructive species in active sand dunes found to date that has excellent ability to fix sand and plays important roles in maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem stability of Maqu alpine grasslands (Kanget al., 2016). However, because of strong dormancy and low germination rate ofC. brunnescensseeds(seed germination rate is only 14%by current technical means) (Wanget al., 2013; Zhuet al.,2013), the sand-fixing effects ofC. brunnescenswas greatly limited. Our previous observations show that the underground horizontal rhizomes ofC. brunnescensare highly developed.C.brunnescenscould produce more new ramets in the artificially emulated blowouts than in natural conditions, suggesting thatC. brunnescensexhibited strong ability in blowout remediation through rapid clonal expansion capability(Kanget al., 2017b). Our results further confirm thatC. brunnescenscan quickly multiply which depend on highly developed horizontal stems in moving sand dunes and form fixed or semi-fixed sandy lands, and can even form rare herb dunes in certain topographical conditions (Kanget al., 2016a; Maet al., 2017).In the growing season, the underground horizontal stems lengthen constantly, and vertical stems grow at nodes of horizontal rhizomes.After the earth's surface is covered by sand, the vertical rhizomes grow upwards and penetrate through the surface of sand to grow into a new plant, thereby making the underground stems become reticular to fix sand. After a dune is fixed byC. brunnescens, other varieties of fine herbage will intrude, spread and quickly dominant, whileC. brunnescenswill degenerate from the fixed dune and spread to other semi-fixed or moving dunes to keep its population relatively stable (Kanget al., 2016a, 2017a). Recent observations demonstrated that transplanting belowground rhizomes ofC. brunnescensto straw checkerboard technology (SCT)-controlled sand dunes has pronounced windbreak and sand fixation effects in degraded alpine sandy environments, which suggested that the SCT-promoted high reproductive abilities of belowground rhizomes ofC. brunnescenscan successfully facilitate the establishment of ramets and can thus be an effective strategy to restore degraded vegetation in Maqu alpine region of northwestern China (Kanget al., 2017a).However, this technique is time-consuming, laborious and costly; in addition, the digging of plants destroys the original vegetation which is difficult to meet the needs of artificial sand consolidation technology in Maqu desertified alpine regions. Thus, it can be seen that artificial sand fixation through seed reproduction ofC. brunnescensmay be a new way to ecological restore Maqu desertified grasslands.Breaking seed dormancy, promoting rapid germination and seedling formation ofC. brunnescensare the premise and key to ecological restoration of Maqu desertified grasslands.

Up to now,very little is known about the seed dormancy and germination mechanisms ofC. brunnescens. Furthermore, after breaking seed dormancy,feasibility for the seed germination technology ofC.brunnescensto be popularized and applied in Maqu desertified areas is not clear. In this study, we explore a method that can rapidly break the seed dormancy ofC. brunnescensby clarifying the seed biology characteristics and causes of seed dormancy, exploring a method of releasing seed dormancy, and then investigate the growth adaptability, reproductive and sandfixing effects ofC. brunnescensby cultivatingC.brunnescensseedlings to establish living sand barriers on the sand ridges of moving sand dunes. The results of this study can provide important scientific basses for the exploration of sand-fixing technology by appli-cation of herbaceous plants and lay a solid foundation for the popularization and application of the seed germination technology and sand fixation technology ofC. brunnescensto restore and reconstruct Maqu alpine degraded grasslands.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study area

The study area is located in Grassland Station of Maqu County (GSMC), Gansu Province in Northwest China (33°06′30′′N -34°30′15′′N, 100°45′45′′E -102°29′00′′E; Elevation: 3,300-3,700 m). This area belongs to "the first terrace of the Yellow River" and has an obvious plateau continental climate. The four seasons in the area are not distinct in a year, and the mean annual temperature and annual mean precipitation are 1.1 °C and 615.5 mm, respectively, while the annual average evaporation is 1,353.4 mm. Main plant species include herbs such asC. brunnescens,Kobresia robust,Leymus secalinusandPolygonum viviparumand shrubs such asSalix oritrepha,Hippophae rhamnoidesandPotentilla fruticosa. Main soil types are alpine meadow, subalpine meadow,meadow, swamp and peat, among which meadow soil is the most widely distributed area in the study area.The landscape consists of fixed, semi-fixed, and moving sand dunes dominated byC. brunnescens. Wind erosion in the area(especially on both sides of the Yellow River) is very serious during winter and spring,which results in severe environmental conditions(Kanget al., 2017). On semi-fixed and moving sand dunes,C. brunnescenspopulations frequently undergo different levels of sand burial and wind erosion imposed by strong winds.

Mature fruits ofC. brunnescenswere harvested in July, 2017 in the desertified areas in GSMC. Fresh fruits were dried at room temperature, and then gently crushed to release seeds and washed three times to remove impurities.Seeds were stored in a hop-pocket in a refrigerator (-7 °C). Seeds were treated using the fungicide Phygon before the germination process.Seed germination tests were performed with four replicates of 50 seeds each in filter paper petri dishes(diameter 11 cm) lined with two filter paper disks moistened with distilled water.Seed germination was examined everyday and seedlings were removed.

2.2 Seed germination experiments of C. brunne‐scens (July to September, 2017)

In this part, we firstly measured the vigor of seeds to determine whether they have vigor or not. Secondly, seeds were treated with different physical measures to determine the causes and types of seed dormancy. Then, the comprehensive treatments of H2SO4scarification and NaOH solution immersion, fluctuating temperature and GA3were applied to reveal the inherent logic of seed germination. Finally, the technical method that can promote the rapid germination of seeds was obtained.

2.3 Biological characteristics of seeds-morphological and anatomical characteristics, and viability of seeds

The basic morphological characteristics ofC.brunnescensseeds were described by observing their shape, color, size and quality.The shape and color of seeds were described by observation, and the long axis, short axis, and thickness of seeds (five groups of 30 seeds were measured to determine average seed size) where measured by a 0-150 mm electronic digital caliper. Five groups of 1,000 seeds were weighed after collection to determine average seed weight.

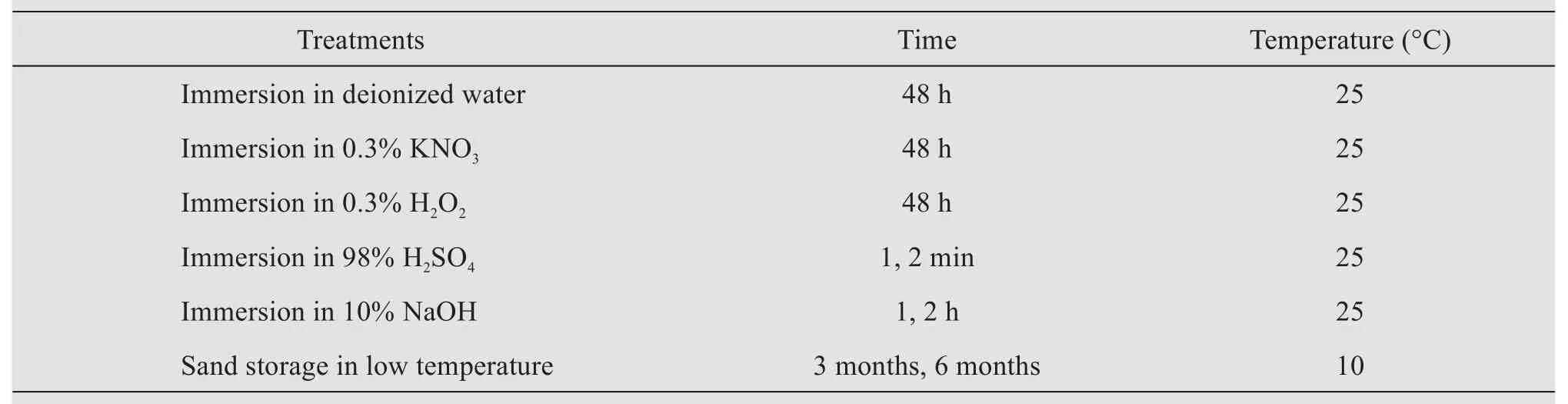

Because the seed coats ofC. brunnescensare hard to cut and hardly absorbs water without any treatment, the seeds were softened, and then anatomical characteristics and viability were observed.The different softening methods of seeds are presented in Table 1. After the seed coats are softened, 150 seeds with three replications were randomly selected for dissection and embryo development was observed under a stereomicroscope.

Table 1 The different softening methods of Carex Brunnescens seeds

The seed viability ofC. brunnescenswas determined by TTC staining (Wanget al., 2017). The softened seeds (150 seeds with three replications) were dyed by whole grain dyeing and dyed after longitudinal embryo cutting. Firstly, the seeds were dyed with 0.5% tetrazole solution at 35 °C for 24 h in darkness,then washed with clean water,then identified seed viability under stereo-anatomical microscopy according to the location and degree of dyeing.

2.4 Germination characteristics of seeds under different physical and chemical methods

2.4.1 Physical treatments of seeds

The germination experiment was conducted with four replications, including the following treatments:Seeds were immersed in water at room temperature for 48 h (Control), seeds were immersed in hot water(40, 50, 60 and 70 °C) for 48 h, cut the seed coat(seeds were abraded with 100-mesh sandpaper till a tiny part of embryo appears) and stratification (10 °C)for three months and six months, respectively (Table 2). Fifty seeds were placed in petri dishes with distilled water in an incubator at 25 °C in darkness. The germination rate was recorded after 10 d of incubation period.

2.4.2 Sulfuric acid scarification or immersion in sodium hydroxide of seeds

Seeds were sterilized in 75% ethanol for 1 min,rinsed eight times with distilled water and then soaked with 98% H2SO4for 0, 1, 2, 2.5, 3, 4 and 5 min, respectively or immersed in 10% NaOH for 0,2, 3, 3.5, 4, 4.5 and 5 h, respectively. Seeds were washed with distilled water until the potential of hydrogen (pH) of the seed surface was close to distilled water pH value. Seed germination was tested and cultured in an incubator at 25 °C under dark conditions.Four replications were used for each germination experiment, and seeds not soaked with 98% H2SO4or 10%NaOH were used as control.

2.4.3 Seed germination in fluctuating temperatures in darkness

Seeds were soaked in 98% H2SO4for 2.5 min or 10% NaOH for 3.5 h, and then washed with distilled water until the pH value of seed surface was close to 7.0. Seed germination was determined at a constant temperature of 25 °C (Control) and fluctuating temperatures of 25/5(25 °C in daytime and 5 °C at nighttime),25/10 and 25/15°C in darkness.

2.4.4 Seed germination at different concentrations of gibberellic acid (GA3) solution

Seeds were soaked in 98% H2SO4for 2.5 min or 10% NaOH for 3.5 h, and then washed with distilled water until the pH value of seed surface was close to 7.0. Seed germination was tested in 50, 100 150 and 200 mg/L GA3, then seeds were sealed with parafilm and cultured in incubators for 48 h in darkness at fluctuating temperatures of 25/5°C.Seeds were germinated in distilled water as the control.

2.5 Transplanting experiment of C. brunnescens seedlings cultivated by seed germination technology in sand dunes

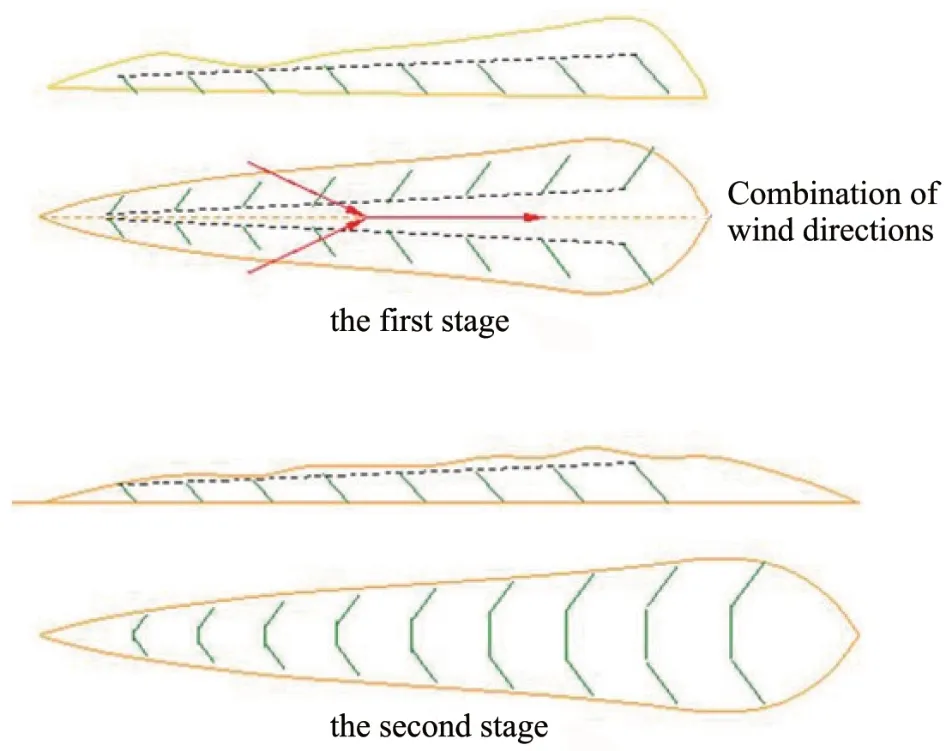

To investigate growth adaptability, reproductive characters and sand-fixing effects ofC. brunnescensseedlings cultivated by seed germination technology,we conducted a transplanting experiment ofC. brunnescensseedlings in sand ridges of sand dunes along the bank of the Yellow River,8 km from GSMC (with an estimated area of 9.8 km2) (April 2018 to September, 2019). Seeds ofC. brunnescenswere germinated as described above. In early April, 2018, a convenient greenhouse facing south from north was established to rapidly breedC.brunnescensseedlings by pot cultivation. The tested soil samples were collected from GSMC where the strong sand-fixing speciesC. brunnescensis naturally distributed. The summary statistics of soil properties are described as follows: The concentrations of soil organic carbon (SOC), available nitrogen (AN), available phosphorus (AP) and available potassium (AK) in soil were 306.4 mg/kg,796.6 μg/kg, 230.8 μg/kg and 46.3 μg/kg dry soil, respectively. The soil described above was dried out,crushed, and screened with a 2-mm sieve. Seeds ofC. brunnescenswere germinated and then seedlings were transplanted into degradable plastic pots(15 cm height×20 cm diameter), and then covered with 0.3-0.5 cm of thick fine sand on the surface of the seedlings. All pots were filled with 3 kg sandy soil and fully irrigated with water. Soil water content(SWC) was maintained at 70% of field water capacity(FWC) by weighing. After three weeks, plants were thinned out and three healthy plants were kept, and then all plants were transplanted into the sand dunes.The transplanting experiment was divided into two stages(Figure 1).

In the first stage (April to September, 2018), two experimental sites were designed: sand ridges without transplantingC.brunnescens(SRWT)and sand ridges transplantingC. brunnescens(SRT). In the second stage (April to September, 2019), two experimental sites were designed: sand ridges leveled by wind erosion without transplantingC. brunnescens(SRLW-WT) and sand ridges leveled by wind erosion transplantingC. brunnescens(SRLWT). The living sand barrier ofC. brunnescens(plant spacing: 15-20 cm)was constructed with a distance of 10-20 m by transplantingC. brunnescensseedlings in the perpendicular direction to the main wind in the middle and lower parts of the sand ridges on both sides of the moving sand dunes (SRWT as control). Then, when the sand ridges were leveled by wind erosion, the living sand barrier(plant spacing:15-20 cm;spacing of sand barrier: 0.5-1.0 m) ofC. brunnescenswas reestablished by large-scale transplanting ofC. brunnescensseedlings in the perpendicular direction to the main wind on the wind-eroded flat ground (SRLWWT as control). Finally, the live sand barriers on the left and right sides are connected. In SRT and SRLWT experimental sites, each transplanting plot (10m×10m; 104 seedlings per plot transplanted) was surrounded by a buffer zone of 1.0 m.There were four replicated plots in each experimental site. After the plants were harvested at the end of the growth period (early September 2018 and 2019), newly-generated ramets (excluding the dead plants) were dug out (1m×1m; repeat four times)and washed three times with water for further morphological and biomass analysis.

Figure 1 Model figure of living sand barrier control for moving sand ridges of Carex Brunnescens

2.6 Measurements of samples

2.6.1 Growth-related parameters of C. brunnescens

Plant height (PH) was measured using a ruler(0.1 m precision). Population density (PD) was obtained by counting all newly-generated ramets in each plot (1m×1m). Vegetation coverage (VC: projected cover;%)was calculated using digital imagery.

The underground rhizomes were excavated, and the total number of underground rhizomes (NUR)was counted in each experimental plot (1m×1m).Total length of underground rhizomes (TUR) was calculated by measuring the length of each underground rhizome. Fresh weight of above-underground biomass(FWAUB)in each plot(1m×1m)was calculated by weighting (electronic scale with 0.001 g precision).

2.6.2 Soil nutrients

Different depths of soil samples were collected in each experimental site (i.e., SRT SRWT and SRLWWT) after all the newly-generated ramets were harvested in September 2018, 2019. Specifically, 4-6 subsamples were respectively collected at three soil layers (0-15, 15-30, and 30-50 cm) in each experimental plot, then subsamples from the same soil layer in each plot were mixed into a composite sample.Soil samples were placed in plastic bags and taken to the laboratory for soil chemical analyses. These samples were air-dried at room temperature for 30 d and sieved by a 2 mm mesh. Soil organic carbon (SOC)was measured following the K2Cr2O7-H2SO4oxidation method of Walkley and Black (Kanget al., 2015,2017a). Moreover, soil available nitrogen (AN) was determined by the alkaline diffusion method, available phosphorus (AP) was determined by the Bray method, and available potassium (AK) was measured using the ammonium acetate extract method (Bao 2000;Kanget al.,2017a).

2.7 Data analysis

All experimental data was analyzed using the SPSS program for Windows Version 13.0 (SPSS Inc.,Chicago, Illinois, 1975). Duncan's multiple range tests and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for a completely randomized design were used to compare the germination rate of different seed germination experiments, and the positive effects of transplanting experiment of pot cultivatedC. brunnescensseedlings in sand dunes on the growth-related (PH,PD, VC, NUR, TUR and FWAU B) and soil nutrients(SOC,AN,AP,AK) indices. The least significant difference (LSD) tests were performed to detect the significance of the determined data between means at a significance level ofP<0.05.

3 Results

3.1 Morphological and anatomical characteristics,and viability of C. brunnescens seeds

C. brunnescensseeds are brown, triangular, with long or short beaks and hard seed coats. The seeds ofC. brunnescensare small, with an average length,width and thickness of 2.34±0.16 mm, 1.36±0.11 mm and 1.25±0.12 mm, respectively. The average weight of 1,000 seeds is 1.89±0.11 g. According to the anatomical observation of 150 seeds, 68.0% (102 seeds)had complete embryonic structure while 32.0% (48 seeds) were abnormal or empty. Although the seeds have reached the size and color of mature seeds, there are still sterile seeds in the screened seeds.TTC staining shows that 104 embryos (69.3%) of 150 softened seeds mostly stained red, 22 seeds (14.7%) were very light stained, and the remaining 24 seeds (16.0%)were not stained at all. Seeds that were lightly stained or were not stained were considered to be the seeds that could not normally develop.The seed viability ofC. brunnescensbelongs to the middle to high level,with an average of 69.3%.

3.2 Effects of different physical treatments on the seed germination of C. brunnescens

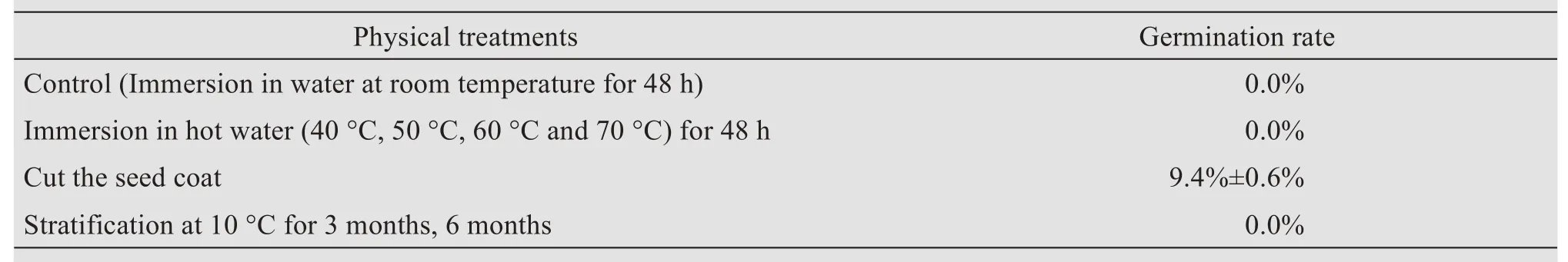

The seeds ofC.brunnescensremained dormant after being immersed in water at room temperature for 48 h, immersed in hot water (40, 50, 60 and 70 °C)for 48 h and stratified at 10 °C for three months and six months, while the seed dormancy ofC. brunnescenswas broken after cutting the seed coat at 25 °C in darkness for 10 d, but the germination rate was very low,only 9.4%(Table 2).

Table 2 Effects of physical treatments on seed germination of Carex Brunnescens

3.3 Sulfuric acid scarification (98% H2SO4) or immersion in sodium hydroxide (10%NaOH) positively broke the dormancy of C.brunnescens seeds

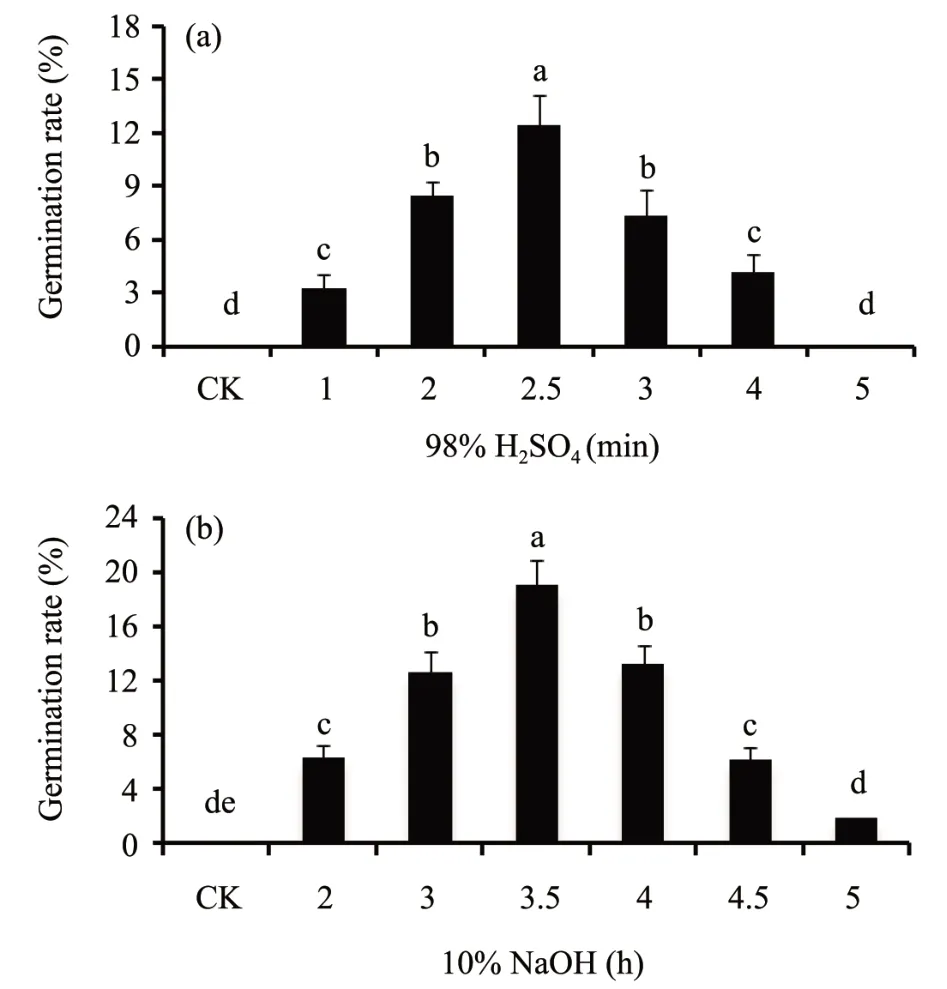

Sulfuric acidscarification (98% H2SO4) positively promoted the seed germination ofC. brunnescens(Figure 2a). The germination rate treated with 98%H2SO4was significantly more than that in control treatment. The highest germination rate of 12.4% was observed when seeds were treated with 98% H2SO4for 2.5 min and the lowest germination rate was observed in control (without treating with 98% H2SO4and seeds remained dormant). Meanwhile, the seed germination rate ofC. brunnescenswas also discovered to be greatly promoted by sodium hydroxide(10% NaOH) for 3.5 h, and the germination rate was better than treated with 98% H2SO4(Figure 2b). The highest germination rate of 19.1% was observed when seeds treated with 10% NaOH for 3.5 h and the lowest germination rate (seeds remained dormant) was observed without treating with 10%NaOH(Control).

3.4 Fluctuating temperatures not only greatly promoted the germination of C. brunnescens seed but also made the seed germination more uniform

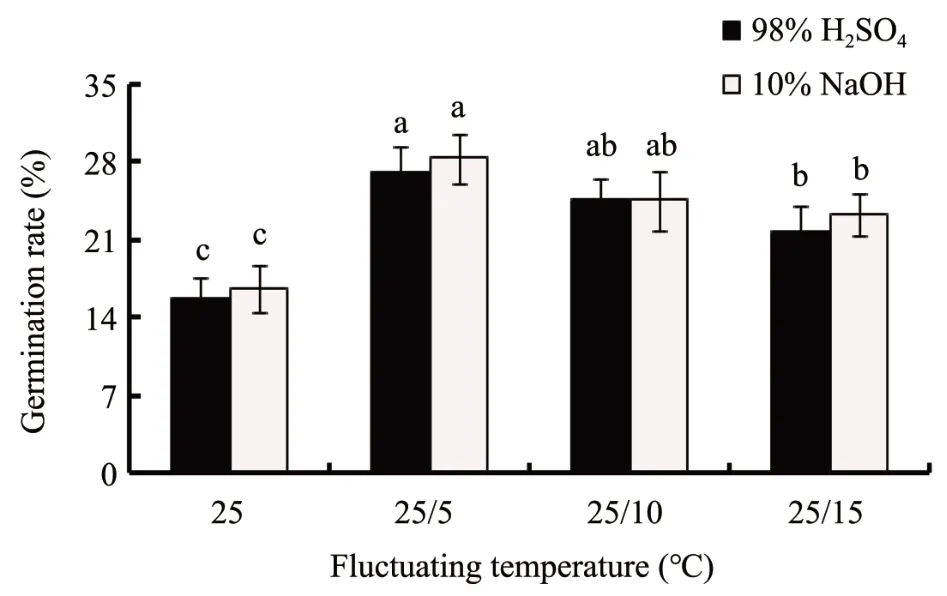

The different fluctuating temperatures played important roles in improving the seed germination rate ofC. brunnescenstreated by 98% H2SO4for 2.5 min or 10%NaOH for 3.5 h(Figure 3).The highest germination rates of 27.2% and 28.4% were observed when seeds were treated with 98% H2SO4for 2.5 min or 10% NaOH for 3.5 h in variable temperature treatment at 25/5 °C, and the lowest germination rates of 15.7% and 16.7% were observed when seeds treated with 98%H2SO4or 10%NaOH at a constant temperature of 25°C.It is worth mentioning that the seed germination rate ofC. brunnescensin fluctuating temperatures at 25/5 °C and 25/10 °C were more uniform than that in constant temperature at 25 °C. The better uniform germination range was observed when seeds germinated in variable temperature treatment at 25/5°C(Figure 3).

3.5 GA3 further advanced the germination rate of C. brunnescens seeds treated with 98%H2SO4 for 2.5 min or 10% NaOH for 3.5 h at 25/5 °C

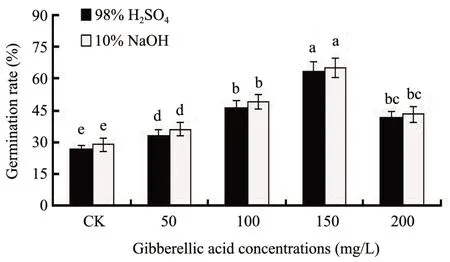

Seeds treated with 98% H2SO4for 2.5 min or 10% NaOH for 3.5 h were observed to be very sensitive to GA3when seeds were in variable temperature treatment at 25/5°C in darkness(Figure 4).GA3concentrations at 50 100, 150 and 200 mg/L had significant effects on the seed germination rate ofC. brunnescenswhen seeds were treated with 98% H2SO4or 10% NaOH at 25/5 °C in darkness. The germination rate of seeds treated with 98% H2SO4or 10% NaOH(25/5 °C) were greatly increased under different con-centrations of GA3, and the highest germination rates of 63.7% and 65.1% were observed when seeds were treated with 150 mg/L GA3for 24 h and the lowest germination rates of 27.1% and 29.0% were observed when seeds germinated without treating with GA3(Figure 3).

Figure 2 Effect of sulfuric acid scarification(98%H2SO4)or sodium hydroxide(10%NaOH)soak on the seed germination percentage of Carex Brunnescens.After treated with 98%H2SO4 for 0,1,2,2.5,3,4 and 5 min(a)or 10%NaOH for 0,2,3,3.5,4,4.5 and 5 h(b),seeds were germinated at 25°C in darkness for 10 d.Values are means±SD(n=50).Columns with different letters indicate significant difference at P <0.05(LSD test,the same as below)

Figure 3 Effect of various temperature regimes on the seed germination percentage of Carex Brunnescens.After treated with 98%H2SO4 for 2.5 min or 10%NaOH 3.5 h,seeds were germinated in darkness at fluctuating temperature regimes(25/5,25/10 and 25/15°C)and constant temperature regime of 25 °C for 10 d.Values are means±SD(n=50).Columns withdifferent letters indicate significant difference at P <0.05

Figure 4 Effect of different gibberellic acid(GA3)concentrations on the seed germination percentage of Carex Brunnescens.After treated with 98%H2SO4 for 2.5 min or 10%NaOH 3.5 h,seeds were placed at 25/5°C in darkness under different GA3 concentrations(0,50,100,150,and 200 mg/L)for 48 h,and then germinated at 25/5°C in darkness for 10 d.Values are means±SD(n=50).Columns with different letters indicate significant difference at P <0.05

3.6 Growth characteristics and sand fixing effects of ramets after establishment of living sand barrier of C. brunnescens in the sand ridges of moving sand dunes

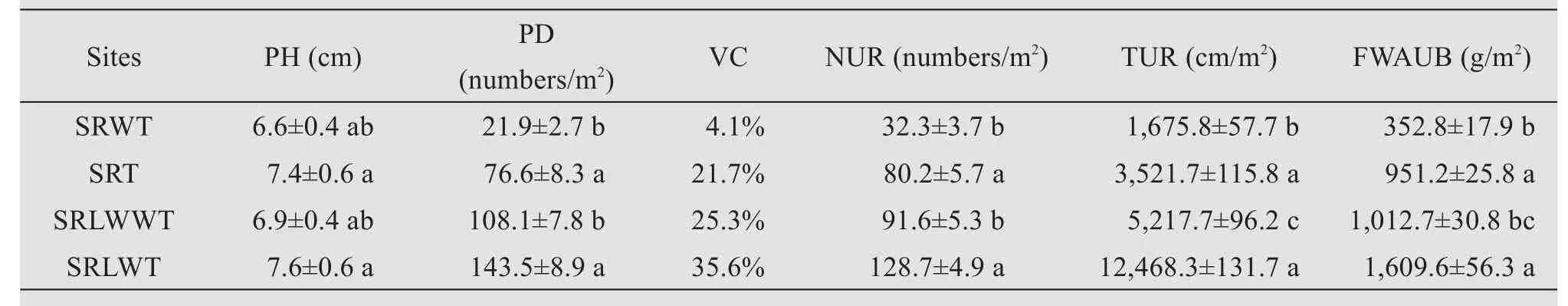

The growth performance and sand fixing effects ofC. brunnescensramets were significantly improved when the living sand barrier ofC. brunnescenswas established in the sand ridges of moving sand dunes. Compared with SRWT treatment, the SRT treatment significantly increased PD by 249.8%, VC by 17.6%, NUR by 148.3%, TUR by 110.2% and FWAUB by 169.6%, respectively (Table 3). The positive effects of reestablishment of living sand barrier on the growth performance and sand fixing effects ofC. brunnescenswere also confirmed in the leveled sand ridges of moving sand dunes by wind erosion (Table 3). Compared with SRLWWT treatment, the SRLWT treatment significantly increased PD by 32.0%,VC by 36.5%, NUR by 40.5%,TUR by 140.0% and FWAUB by 58.9%, respectively(Table 3).

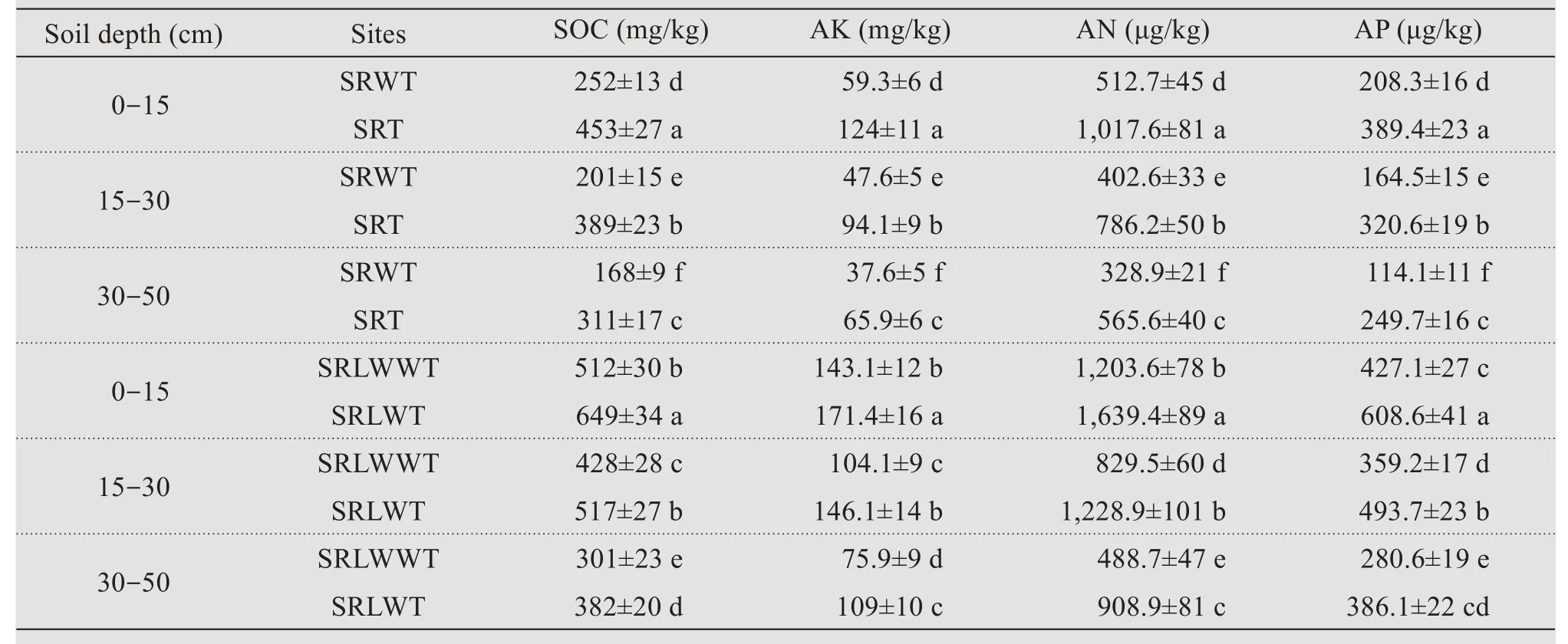

The establishment of living sand barrier ofC.brunnescenshad significant effects on soil nutrient properties.Compared with SRWT treatment(0-15 cm soil depth), the SRT treatment significantly increased SOC by 79.8%, AN by 109.1%, AP by 98.5%, and AK by 86.9%, respectively (Table 4). Similarly, compared with RLWWT treatment (0-15 cm soil depth),the SRLWT treatment significantly increased SOC by 26.8%, AN by 19.8%, AP by 36.2%, and AK by 42.5%, respectively (Table 4). Similar tendencies were also observed in 15-30 and 30-50 cm soil depths, and the SOC, AN, AP, and AK contents decreased with the increase of soil depth(Table 4).

Table 3 Changes of plant height(PH),population density(PD)and vegetation coverage(VC),number of underground rhizomes(NUR),total length of underground rhizomes(TUR)and fresh weight of above-underground biomass(FWAUB)of Carex Brunnescens transplanted in the sand ridges of the moving dunes and the leveled sand ridges of moving dunes by wind erosion

Table 4 Changes of soil organic matter(SOC),available nitrogen(AN),available phosphorus(AP)and available potassium(AK)after transplanting Carex Brunnescens in the sand ridges of the moving dunes and the leveled sand ridges of the moving dunes by wind erosion

4 Discussions

4.1 Mechanical obstacle of seed coat is an important reason that leads to the dormancy of C. brunnescens seeds

Seed dormancy is a biological adaptation for plants which is extremely beneficial for preservation and reproduction of plant species (Zhang and Wang,2015). In general, most plant seeds, except recalcitrant seeds, have strong or weak dormancy characteristics, especially in cold and temperate zones (Yanget al., 2006; Liet al., 2016a). Seed dormancy of many plants is strongly induced by the pericarp and/or seed coat and most can be effectively broken by mechanical and acid scarification (Adkinset al.,2002;Phartyalet al.,2005;Kanget al.,2016b).In an alpine sandy environment,C. brunnescensseeds have a hard seed coat which weakens the sexual reproductive ability of seeds. Our observations indicate that although the average viability ofC. brunnescensseeds was only 69.3%, at least 70% ofC. brunnescensseeds had germination potential. Most results have shown that sulfuric acid scarification (98% H2SO4) and mechanical grinding, fluctuating temperature and gibberellic acid(GA3)treatments were considered as effective ways to break the coat-imposed dormancy for many plants(Bakeret al., 2005; Finch-Savage and Leubner-Metzger, 2006; Devillaloboset al., 2007). In this study,C. brunnescensseeds still did not germinate whether treated with water at room temperature, hot water at different temperatures or stratified at different times. However, seeds treated with mechanical scarification (cutting the seed coat) germinated, even if the germination rate was very low (9.4%)(Table 2).Moreover, 98% H2SO4scarification (2.5 min) or 10%NaOH immersion (3.5 h) positively broke the seed dormancy and made the seed germination rate reach to 12.1% and 19.4% (Figure 2), respectively. Thus,we think thatC. brunnescensendocarp impermeability to water uptake and gaseous exchange may be one of the main reasons for seed dormancy. Results have demonstrated that GA3application played significant roles in promoting seed germination, especially for seeds ofEmpetrum hermaphroditum,Empetrum hermaphroditum,andNitraria tangutorumthat have hard seed coats (Baskinet al., 2002; Tianet al., 2003;Kanget al., 2016b). GA3application markedly raised the germination rate of the optimal 98% H2SO4or 10% NaOH-treated seeds, and the highest germination rates of 63.7% and 65.1% were observed when seeds were treated with 150 mg/L GA3for 24 h (Figures 3, 4). Perhaps the reason for this result may be that GA3breaks the seed coat dormancy by enhancing the embryo growth potential and/or by decreasing mechanical inhibition, when seed germination has been initiated (Finch-Savage and Leubner-Metzger, 2006).However, although seed germination rate ofC. brunnescensachieved to 65.1%,about 35%of the seeds remained dormant(Figure 4).Therefore,it was concluded that at least 65% of embryos ofC. brunnescensseeds do not have dormancy, the seed dormancy belongs to a comprehensive dormancy, and the mechanical obstacle of the coat is one of the main reasons that lead to the dormancy ofC.brunnescensseeds.Our result supports the viewpoints of Kanget al. (2016c) onKobresia robusta, and believes that seed dormancy is a common phenomenon for many plants growing in alpine regions,and the comprehensive treatments of 98%H2SO4scarification, mechanical grinding, fluctuating temperature and GA3are considered as a effective way to break the dormancy ofC.brunnescensandK.robusta.In alpine habitats, seed germination ofC. brunnescensis seriously controlled by a phylogenetic constraining force which leads to a very low germination rate ofC. brunnescensseeds. Therefore, studying the correlation between seed reproduction characteristics and the phylogeny ofCarexmay help reveal reasons for high dormancy rate of its seeds. Further studies are worthwhile to clarify the complex dormancy and germination mechanism ofC.brunnescensseeds.

4.2 Sand fixation with C. brunnescens and its application in desertified alpine areas

During the process of adapting to various adversity, plants have evolved multiple strategies to adapt to complex environments (Enquist and Nikilas, 2002; Liet al., 2016b). Clonal plants exist widely in the plant kingdom, and the physiological or clonal integration is one of the important adaptive strategies to adapt to heterogenous environments (Ye and Dong, 2011; Luoet al., 2015a,b, 2018). Our previous results show that the clonal plantC. brunnescensdevelops a complex underground structure, and the underground rhizomes at a depth of 50 cm still has the ability to germinate and grow out of the soil;there exists an obvious physiological integration between contiguous clonal ramets ofC.brunnescens(Kanget al.,2016a).The plants produce spindly horizontal rhizomes extending downwards, and the branching type of the underground rhizomes is monoaxial type,while many buds can grow at the top and on the nodes of the rhizomes and develop upwards to form new ramets, thereby realizing spatial extension of genets and continuous renewal of ramets.Thus,C. brunnescensgrows by cloning to produce new ramets linked with stock plants and then form clones (Kanget al., 2016a; Maet al., 2017). Our results further demonstrate thatC.brunnescenscan adopt an adaptation strategy of simultaneous growth of its leaves and flowers and had adaptation features of two flowering and fruiting cycles. As a result,C. brunnescenshas an opportunity of breeding and can produce propagules every year, so that it can retain more genes in an unpredictable blown sand environment (Maet al., 2017). This strategy can enableC. brunnescensto complete breeding tasks quickly when encountering adverse environments in the late growth stage, and avoid the loss of population genes in an adverse environment.

Soil erosion is an important process that influences both surface characters and soil biological potential(Ye and Dong, 2011; Xuet al., 2012). Sand fixation by establishing strong sand-fixing plants is known as one of the most effective ways to control desertification (Wanget al., 2016; Kanget al., 2017b). Thus,choosing well-adapted plants is critically important in restoring and stabilizing sand dunes (Gonget al.,2014;Wanget al., 2016). Previous results have demonstrated that establishment of stable artificial sandfixing plant communities with straw checkerboard technique (SCT) is considered to be an efficient way of windbreak and sand fixation in many arid and semi-arid areas of China (Qiuet al., 2004; Kanget al., 2015, 2017b; Maet al., 2015). Our studies have demonstrated thatC. brunnescensnot only exhibit strong ability in blowout remediation, but also pronounce windbreak and sand fixation effects by transplanting belowground rhizomes to SCT-controlled sand dunes (Kanget al., 2017a,b). Although this sand-fixing technology (SCT) is very effective, it is time-consuming, laborious and costly. In our study,we have invented a technology method that can effec-tively fix sand dunes by establishingC. brunnescensseedlings as living sand barriers (Figure 1). Result show that a significant negative correlation between vegetation coverage and wind erosion has been previously documented (Haiet al., 2002; Xu and Liu,2012; Zhanget al., 2016). In our study, PD and VC varied from 21.9 numbers/m2and 4.1% in the SRWT to 76.6 numbers/m2and 21.7% in the SRT and, surprisingly, to 143.5 numbers/m2and 35.6% in the SRLWT.Similar trends of NUR, TUR and FWAUB ofC. brunnescenswere also observed in SRWT,SRT and SRLWT (Table 3). Our result supports the viewpoint of Haiet al. (2002) that VC at 35%-40%was the effective range to control wind erosion which could significantly weaken the wind erosion effect. Moreover, our previous results demonstrate that forC. brunnescens, the following conditions are well-documented to have significant influence on wind erosion and sand burial (Kanget al., 2016a,2017a): PD at 145-156 numbers/m2, VC at 31.2%-39.3%, and TUR at 11,223 cm/m2. The results of this study are consistent with those of Haiet al.(2002)and Kanget al. (2016a, 2017a). In addition, our results confirm that establishment of living sand barriers by transplantingC. brunnescensseedlings in the SRT treatment also significantly increased soil nutrient contents (SOC, AN, AP and AK) compared with SRWT treatment, and nutrient contents can be further increased by reestablishingC. brunnescensseedlings in the SRLWT treatment (Table 4). These results support a positive role ofC.brunnescensin weakening the wind erosion effect and improving soil fertility by transplantingC. brunnescensseedlings as living sand barriers, indicating that sand fixation withC. brunnescenscan be applied in Maqu alpine desertified areas.

5 Conclusions

In this study, we successfully explored a method that can rapidly promote the seed germination ofC.brunnescens. Seed germination reached a peak of 63.7%or 65.1%when seeds were treated with 150 mg/L GA3(24 h)followed by soaking 98% H2SO4(2.5 min)or 10% NaOH (3.5 h), and then germinated (25/5 °C)in darkness for 10 d. Also, we explored a technical method of establishingC. brunnescensseedlings as living sand barriers to control desertification in the sand ridges of the moving dunes (plant spacing 20 cm; spacing: 10-20 m) and the leveled sand ridges of moving dunes by wind erosion (plant spacing:20 cm; spacing 0.5-1.0 m). Thus, the seed germination technology combined with sand fixation technology ofC. brunnescenscan shorten the seed germination period and make seedling establishment much easier, which opens a new perspective to restore and reconstruct the Maqu alpine desertified grasslands.

Acknowledgments:

This study was supported by the Project of the Youth Talent Development Fund of the Northwest Institute of Eco-Environment and Resources, Chinese Academy of Science (CAREERI) (Y851C81001), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41877162),and the Instrument Functional Development Project from the Technology Service Center of CAREERI(Y429C51007). The authors are very grateful to the anonymous reviewers and editors for their critical review and comments which helped to improve and clarify this paper.

Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions2020年5期

Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions2020年5期

- Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions的其它文章

- Variation characteristics and prediction of pollutant concentration during winter in Lanzhou New District,China

- Variation in water source of sand-binding vegetation across a chronosequence of artificial desert revegetation in Northwest China

- Calculation of salt-frost heave of sulfate saline soil due to long-term freeze-thaw cycles

- Processes of runoff in seasonally-frozen ground about a forested catchment of semiarid mountains

- Effect of debris on seasonal ice melt(2016-2018)on Ponkar Glacier,Manang,Nepal

- Editors-in-Chief Yuanming Lai and Ximing Cai