Intractable hematuria due to giant prostatic hyperplasia effectively treated with prostatic artery embolization

Issam Kably , Alexander Bode

a Jackson Memorial Hospital, Department of Vascular and Interventional Radiology (R-109), PO Box 016960, Miami, FL, USA

b University of Miami Leonard M. Miller School of Medicine, 1600 NW 10th Ave #1140, Miami, FL, USA

KEYWORDS Hematuria;Embolization;Giant prostatic hyperplasia

Abstract Giant prostatic hyperplasia (GPH) is a rare pathology traditionally treated with an open suprapubic prostatectomy. This procedure is risky, and fatal hemorrhagic complications can occur.Often,patients with GPH present with diminished renal function due to obstructive nephropathy, making them unfit for less invasive endovascular therapies using traditional contrast agents. Here we present a case of a patient with intractable hematuria due to GPH,as well as diminished renal function,who was successfully treated using prostatic artery embolization with CO2 digital subtraction arteriography as a contrast agent.

1. Introduction

Giant prostatic hyperplasia (GPH) is a rare entity that typically manifests with severe lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), obstructive nephropathy, and in some cases hematuria. Traditionally, GPH is treated by an open suprapubic prostatectomy. However, oftentimes age,comorbidities, and the risk of hemorrhagic complications can be contraindications [1]. Prostatic artery embolization(PAE)is a minimally invasive procedure that can be used to treat benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH), resulting in a lower risk of hemorrhagic complications and decreased hospital stays [2].

Here, we report a case of GPH presenting with urinary retention, intractable hematuria, and significant renal impairment that was treated with PAE and carbon dioxide(CO2) digital subtraction angiography to achieve effective hemostasis.Based on our review,this is the first GPH of this size that has been treated in such a manner.

2. Case report

A 65-year-old male with a decade-long history of progressive LUTS secondary to prostatic hypertrophy presented with a 2-month history of macroscopic hematuria and urinary retention. The patient had undergone a failed transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) procedure 5 years prior,as a computed tomography(CT)1 year after the procedure revealed a prostate size of 350 mL. Prostatespecific antigen (PSA) was elevated to a peak of 60 ng/mL,and biopsies on three occasions were negative for prostate cancer. Two months prior to presentation, the patient was offered open prostatectomy, but declined despite worsening symptoms.

The patient continued to decline, with multiple emergency department (ED) visits due to worsening bouts of hematuria. The patient’s hemoglobin (Hb) levels were between 70 g/L and 90 g/L, and he required emergent transfusion on multiple occasions. On this most recent ED visit, the patient fainted after a severe bout of hematuria and was admitted.

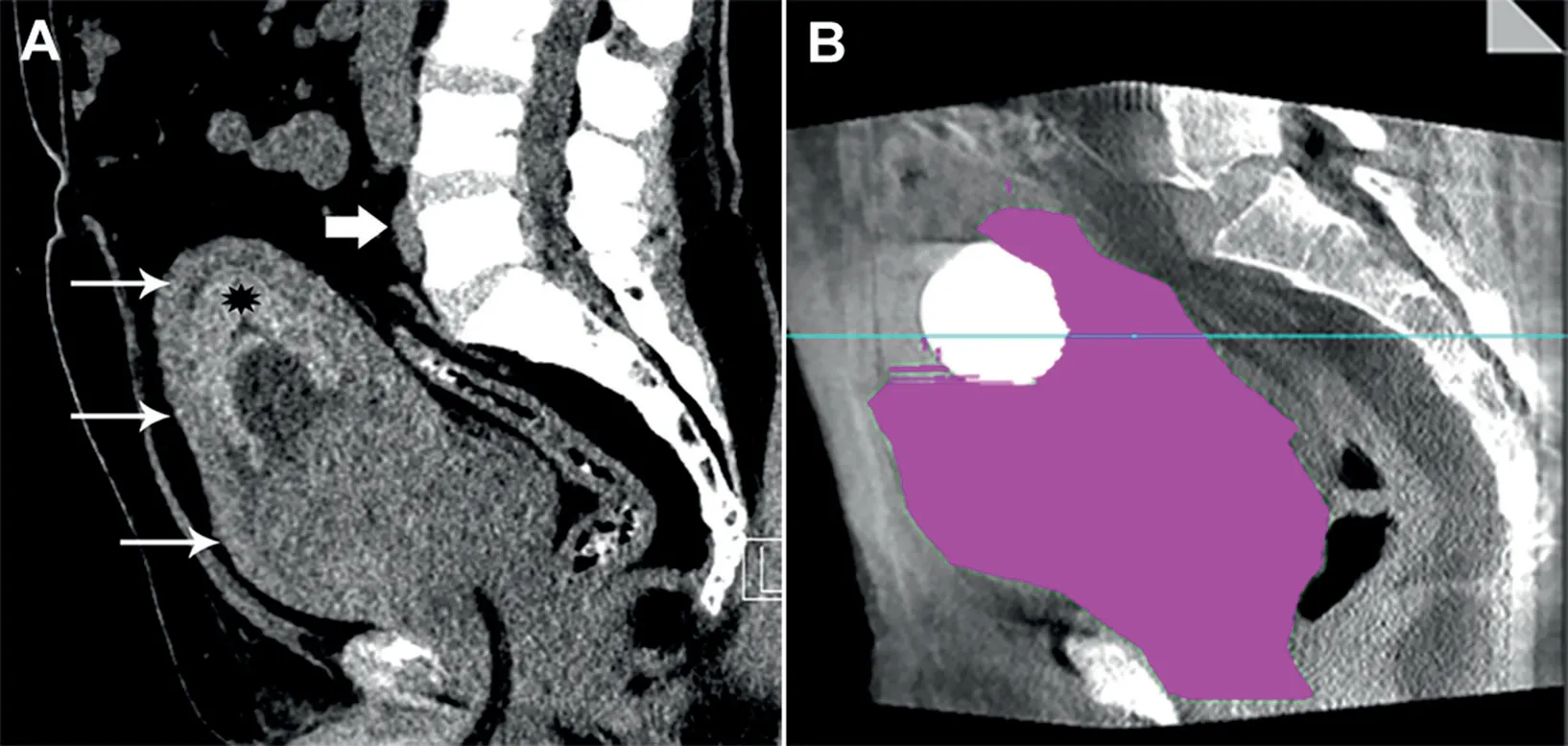

On evaluation, the patient was anuric with suprapubic tenderness, but hemodynamically stable. Non-contrast CT demonstrated an enlarged prostate(724 mL),bladder wall thickening, severe bilateral nephrosis with cortical atrophy, and intravesical material consistent with blood products (Fig. 1). Laboratory values showed Hb 71 g/L,hematocrit 24%, creatinine 16.5 mg/L, and an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 42 mL/min/1.73 m2.Urinalysis showed hematuria >182/HPF.Continues bladder washout was commenced, and conservative management over 6 days failed to improve the patient’s hematuria.The patient was then referred to our service for bilateral nephrostomies and PAE.

Figure 1 Pre-PAE CT demonstrating giant prostate. (A) Preprocedural CT scan demonstrated massively enlarged prostate gland (thin arrows) with a Foley catheter in place.Hyperdense material seen in the bladder lumen (asterisk) was consistent with ostensible blood product. The iliac artery bifurcation (thick arrow) was noted on pre-procedural imaging to avoid initial pelvic runoff with injection of iodinated contrast media; (B) Manual segmentation on the volumetric cone beam CT images yielded a prostate volume of 724 mL.PAE,prostatic artery embolization;CT,computed tomography.

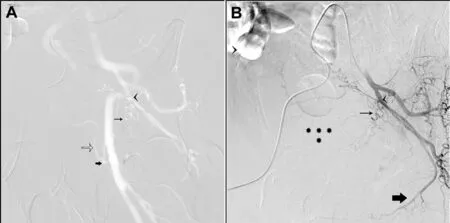

Figure 2 CO2 digitally subtracted angiography (DSA) visualization of the left internal iliac and iodinated contrast confirmation of variant anatomy.(A)CO2 DSA of the left internal iliac artery in a 45-degree ipsilateral oblique demonstrated the origin of the left prostate artery (thin black arrow) originating from a common trunk with the vesical arteries (arrowhead)from the anterior division of the left internal iliac artery; the left obturator artery was not identified. CO2 DSA allowed concomitant opacification of the ipsilateral external iliac artery,which exhibited an aberrant extra pelvic obturator artery(thick black arrow), arising from a common trunk with the inferior epigastric artery(unfilled arrow);(B)The left prostatic artery was tortuous (thin black arrow) giving intra-glandular branches to the left prostatic lobe (asterisks); the left internal pudendal (thick black arrow) artery had a normal intrapelvic course. CO2, carbon dioxide; DSA, digitally subtracted angiography.

During PAE, a right femoral artery access was established. A 4 Fr cobra glide (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) catheter was positioned in the left internal iliac artery. Twenty-five mL of CO2was injected into the left internal iliac artery,allowing us to obtain a digital subtraction angiography(DSA) at 6 frames/second (Fig. 2). This allowed simultaneous visualization of the left prostatic artery arising from a common trunk with the vesical arteries. To confirm left prostatic artery origin 12 mL of half-diluted Visipaque 320 mg/mL (GE healthcare, Princeton, NJ, USA) was injected. The left prostatic artery was then catheterized with a 2.4 Fr Progreat Microcatheter (Terumo, Somerset,NJ, USA) and a 0.029 m steerable guidewire (Boston Scientific, Plymouth, MN, USA). Contrast cone beam CT confirmation demonstrated exclusive enhancement of the left median lobe of the prostate,suggesting the presence of a lateral prostatic artery arising from an aberrant extrapelvic obturator artery previously identified on the CO2angiogram. We elected not to pursue this lateral vessel as our primary endpoint was a hemostatic effect in an actively bleeding patient. The left prostatic artery was then embolized with 12 mL of an embolic mixture comprised of 300-500 μm Embosphere particles (Merit Medical, South Jordan, UT, USA) (Fig. 3).

The right prostatic artery was then identified and catheterized exclusively using CO2DSA of the right internal iliac artery (Fig. 4A). Contrast cone beam CT confirmation was obtained and the artery was embolized until stasis with 13 mL of the same embolic mixture(Fig.4B).The total dose of iodinated contrast media injected was 25 mL of halfdiluted Visipaque 320 mg/mL. There was immediate control of the bleeding and there was no immediate or delayed post-procedural complications. The next morning,the patient’s urine was clear, and he was discharged with Foley catheter in place and oral ciprofloxacin.

At 1-month post PAE there was a return of Hb levels to baseline of 101 g/L, improvement in serum creatinine to 13 mg/L, and a reduction in PSA to 30 ng/mL. Glandular volume was also reduced to 410 mL. Despite this, the patient failed a voiding trial. The patient was scheduled for urodynamic study to rule-out dysfunctional bladder and evaluate potential benefit from radical prostatectomy.

Figure 3 Contrast enhanced visualization of left prostatic artery. Contrast enhanced cone beam CT in a coronal oblique view demonstrates intense blush of the left prostate median lobe (asterisks). CT, computed tomography.

Figure 4 CO2 DSA visualization of right internal iliac and prostatic arteries.(A)CO2 DSA of the right internal iliac artery in a 45-degree ipsilateral oblique perfectly delineated the pelvic vasculature. The right prostate artery (thin black arrows) was unambiguously identified arising from a common trunk with the vesical arteries (thick black arrow) branching from the anterior division of the right internal iliac artery.CO2 opacified the intra-glandular helical prostatic arterial branches(black arrowheads); (B) Contrast cone beam CT showed right hemi-prostate blush(asterisks),with visualization of the intraglandular helical arterial branches (arrowheads). CO2, carbon dioxide; DSA, digitally subtracted angiography; CT, computed tomography.

3. Discussion

BPH is a common cause of LUTS in older males. Surgical intervention may be required in some cases of BPH and include TURP, holmium laser enucleation of the prostate,and photo selective vaporization of the prostate, although these therapies are only indicated in small and medium sized prostates [3]. GPH is a rare form of BPH defined as a prostate exceeding 500 g [4]. A giant benign prostate exceeding 700 mL is an exceedingly rare occurrence, with only around 10 reported cases in the literature,all of which were managed surgically with open prostatectomy [1].

Prostate volume estimation is essential for both preoperative planning, as well as monitoring the response to therapy in patients with BPH.One common way to estimate glandular volume is using transrectal ultrasound which uses the ellipsoid formula to calculate estimated gland volume.Unfortunately, this technique may not accurately estimate glandular volumes in cases of asymmetric glandular enlargement[5].To avoid this pitfall,we elected to use CT based manual segmentation to obtain a more accurate estimation of glandular volume on pre- and post- procedural imaging.

PAE has been previously shown to be an alternative to treating BPH, as well as intractable hematuria of prostatic origin [2,6]. This option utilizes recent endovascular techniques to selectively occlude arterial feeders to the prostate, resulting in diminished vascularity and prostate size.Unfortunately, due to the natural history of GPH, many patients will present with varying degrees of renal impairment, making them unfit for PAE due to the increased risk of iodinated contrast induced nephropathy (CIN) [7]. In such populations, CO2DSA is an attractive contrast alternative as it is safe in patients with diminished renal function [8]. Although CO2DSA has been used in the pelvis,there have been no reports in the literature of its use in PAE[9]. This is due in part to the technical complexity of the procedure,which requires perfect angiographic mapping of the pelvic vasculature to avoid non-target embolization of rectum and bladder, as well as the lack of familiarity of operators with CO2DSA.

4. Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the largest case of GPH treated with PAE. Despite it is a massively enlarged prostate,diminished renal function, and variant anatomy, effective hemostasis was quickly achieved in this patient using PAE under the guidance of CO2DSA.In the future,PAE with CO2DSA may represent an option in patients with prostatic hematuria even in cases of diminished renal function.

Author contributions

Study design: Issam Kably, Alexander Bode.

Data acquisition: Issam Kably.

Data analysis: Issam Kably, Alexander Bode.

Drafting of manuscript: Alexander Bode, Issam Kably.

Critical revision of the manuscript: Alexander Bode, Issam Kably.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Asian Journal of Urology2020年3期

Asian Journal of Urology2020年3期

- Asian Journal of Urology的其它文章

- Androgen receptor: Functional roles and facets of regulation in urology

- Mesenteric metastases from mature teratoma of the testis: A case report

- Sheathless and fluoroscopy-free retrograde intrarenal surgery: An attractive way of renal stone management in high-volume stone centers

- Efficacy and safety of degarelix in patients with prostate cancer:Results from a phase III study in China

- Survival after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: Multicenter comparison between minimally invasive and open approaches

- Androgen receptor in bladder cancer: A promising therapeutic target