A prospective study of patient reported urinary incontinence among American,Norwegian and Spanish men 1 year after prostatectomy

Ann Holk Stor?s*, Mrtin G. Sn , Oltz Grin ,Ptr Chng , Dtttry Ptil , Ctrin Croini ,Jos Frniso Surz , Mil Cvnrov Jon H?vr Log g, Sophi D. Foss?g

a Department of Oncology, Oslo University Hospital, The Norwegian Radium Hospital, Oslo, Norway

b Department of Urology, Emory University Hospital, Atlanta, USA

c IMIM Hospital del Mar Medical Research Institute,CIBER en Epidemiología y Salud Pública,CIBERESP,Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain

d Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA

e Emory University Hospital, Atlanta, USA

f Hospital Universitary de Bellvitge, Barcelona, Spain

g University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

Abstract Objective: To compare pre- and post-radical prostatectomy (RP) responses in the urinary incontinence domain of Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite-26(EPIC-26)in cohorts from the USA, Norway and Spain.Methods: A prospective study of pre- and 1-year post-treatment responses in American(n=537), Norwegian (n=520) and Spanish (n=111) patients, establishing the prevalence of urinary incontinence defined according to published dichotomization. Thereafter we focused on the response alternatives“occasional dribbling”,pad use and problem experience.A multivariate logistic regression analysis (significance level ≤0.01) considered risk factors for “not retaining total control”.Results: Compared to the European men, the American patients were younger, healthier and more presented with lower risk tumors. Before RP no inter-country differences emerged the prevalence of urinary incontinence (6% ). One-year post-treatment urinary incontinence was described by 30% of the American and 41% of the European patients,occasional dribbling being the most frequent type of urinary leakage.In the multivariate analysis the risk of“not retaining total control” increased almost 3-fold in European compared to American patients, with age and co-morbidity being additional independent risk factor.Conclusion: After RP patients from Spain and Norway reported more unfavorable outcomes by EPIC-26 than the American patients to most of the urinary incontinence items, the difference between the European and American patients remaining in the multivariate analysis.The most frequent post-RP response alternative “occasional dribbling” needs to be validated with pad weighing as “gold standard”.

KEYWORDS Prostate cancer;Radical prostatectomy;Urinary incontinence;Adverse effects

1. Introduction

After radical prostatectomy (RP) prostate cancer (PCa)patients have a long expected lifetime, the 15-year cause-specific survival being 88% -93% [1,2]. Consequently, treatment-related adverse effects may have a long-lasting impact on the survivors’ quality of life, with urinary incontinence being one of the most common adverse effects [3-5].

In today’s practice, many PCa patients search for information about where to expect the best oncologic outcome, together with the least risk of adverse effects.The surgeons and the health administrators are also eager to know whether the treatment given in their institution at least fulfills published standard expectations. However in published studies,the rates of post-RP urinary incontinence vary considerably between institutions and countries[6-8].Some of these differences are associated with differences in patient selection, in surgical approaches and/or not at least on varying definitions of urinary incontinence.Further, most reviews summarizing single institution or international experience are based on cross-sectional observations of adverse mainly physician-assessed effects.

During the last 2 decades it has become evident that the evaluation of any post-RP results requires the assessment of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) of dysfunctions and bother, preferably observed in longitudinal studies. Validated and reliable questionnaires have been developed for this purpose [9]. Using one of the available instruments several national uro-oncological research groups have published their experience achieved during 10-15 years.To facilitate improved inter-study comparison of PROs after treatment for PCa an international consensus group has recommended the use of the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite-26(EPIC-26)[10].However,to the best of our knowledge, only the American-Japanese collaboration has resulted in inter-country comparisons of post-RP urinary adverse effects, based on EPIC instruments [11-13].Our group has previously compared the incidence of post-RP erectile dysfunction as emerging from responses to EPIC-26 completed by American,Spanish and Norwegian patients[14], but comparison of urinary incontinence was not previously done for European-American cohorts.

The current exploratory study meets this challenge regarding patient-reported post-RP urinary incontinence by comparing the responses of the items in the urinary incontinence domain of EPIC-26 reported by patients from America,Spain and Norway,before,and 1 year after prostatectomy.We hypothesized that the unadjusted rate of self-reported urinary incontinence would differ between the patient groups’ 1-year postoperative, but that differences would disappear after adjusting for possibly predictive variables as age, co-morbidity and treatment factors.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study design and patients

This study represents continuing collaboration between research groups from USA (Prostate Cancer Outcomes and Satisfaction Treatment Quality Assessment [PROSTAQA]),Norway (Norwegian Urological Cancer Group [NUCG]) and Spain (Multicentric Spanish Group of Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer,Barcelona)[14,15].The American patients were treated between 2003 and 2006 at nine university-affiliated hospitals. The Norwegian patients were included from 2008-2010, 14 of 19 hospitals performing RP in Norway at that time participated in the study. The Spanish patients were treated from 2003-2005 at two different hospitals.After approval by local ethical committees,a deidentified research data file was created, comprising individual pre- and post-treatment data for the American,Norwegian and Spanish patients,who fulfilled the following eligibility criteria:

- Histologically confirmed PCa

- Clinical stage T1 or T2 tumor

- Known level of pre-treatment prostate-specific antigen(PSA) and Gleason score

- Retropubic, laparoscopic or robot-assisted RP with or without nerve-sparing surgery (unilateral vs. bilateral),though without further details regarding the extent of the surgical procedure.

- No neo-adjuvant androgen deprivation therapy

- Valid responses to all items in the urinary incontinence domain of EPIC-26 before (Baseline) and 1 year after RP [15,16], implying no missing responses to the questionnaire.

The file also contained medical and socio-demographic data (co-morbidities, PCa risk group, age, education and partnership) and information on the surgical approach(nerve-sparing RP: Bilateral, unilateral or no).

2.2. Clinical variables

The risk groups were defined according to European Guidelines on Prostate Cancer treatment from 2012[17].Low-risk:cT1-T2a and Gleason score ≤6 and PSA <10 ng/mL. Intermediate risk: cT2b-T2c and Gleason score 7 and PSA 10-20 ng/mL. High risk: cT3a and/or Gleason score 8-10 and/or PSA >20 ng/mL.

2.3. Pre-treatment variables

Level of education was dichotomized into “l(fā)ess than high school” (low) and “high school or more” (high). Relationship status was dichotomized into “no paired relationship”versus “paired relationship”. Co-morbidity was patientreported as the presence of at least one of the following adverse health conditions: 1. Diabetes; 2. Heart failure and/or myocardial infarction and/or angina; 3. Stroke; 4.Peptic ulcer and/or irritable bowel disease; 5. Asthma,bronchitis and/or breathing problems.

2.4. EPIC-26

The present study is based on the patients’responses to the urinary domain of EPIC-26 or EPIC-50 before treatment and 1 year after RP[15,16,18,19].All items in EPIC-26 are found with identical wording in the EPIC-50. The urinary incontinence domain of EPIC-26 contains four items assessing functional aspects(urinary leakage,urinary control and pad use) and the patient’s problem experience. All four items have four or five response alternatives. For separation of self-reported urinary continence from incontinence we applied Sanda et al’s proposal [20] for dichotomization of the response alternatives [20]:Urinary incontinence during the preceding 4 weeks is reflected by one of the following responses:

- Leakage more than once daily

- Frequent dribbling/no urinary control whatsoever

- Use of ≥one pad daily and/or

- Having any problem with dribbling or leakage of urine Importantly, occasional dribbling without use of pads is not considered to indicate urinary incontinence.

The proportions of patients with urinary incontinence before and after RP were established for each country,and the post-RP changes were described. Thereafter and restricted to patients reporting “total control” pretreatment, the numbers of patients with post-RP “pad use” and “problem” were analyzed.

2.5. Statistics

PASW for PC version 21 (IBM Chicago, IL, USA) was used.Proportions and percentages described binary variables with chi-square tests assessing between different countries. To explore possible associations between pre- and peroperative variables and not retaining “total control”(“occasional dribbling”, “frequent dribbling” and “no urinary control whatsoever”) 1 year post treatment, binary and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed, the independent variables being country of RALP, age, co-morbidity, risk group, and performance of nerve-sparing surgery. Variables with a p-value <0.05 in the binary analyses were included in the multivariate model. Results from logistic regression analyses were expressed as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The p-values <0.01 were considered statistically significant. All tests were two-sided.

3. Results

3.1. Patients

Records for 1353 eligible patients were available. Due to one or more missing answer(s) in the urinary incontinence domain at baseline and/or at 1 year post-RP, 185 patients(USA, n=66; Norway, n=107 and Spain, n=12) were excluded from the analyses leaving 1168 evaluable patients(USA, n=537; Norway, n=520; Spain, n=111).

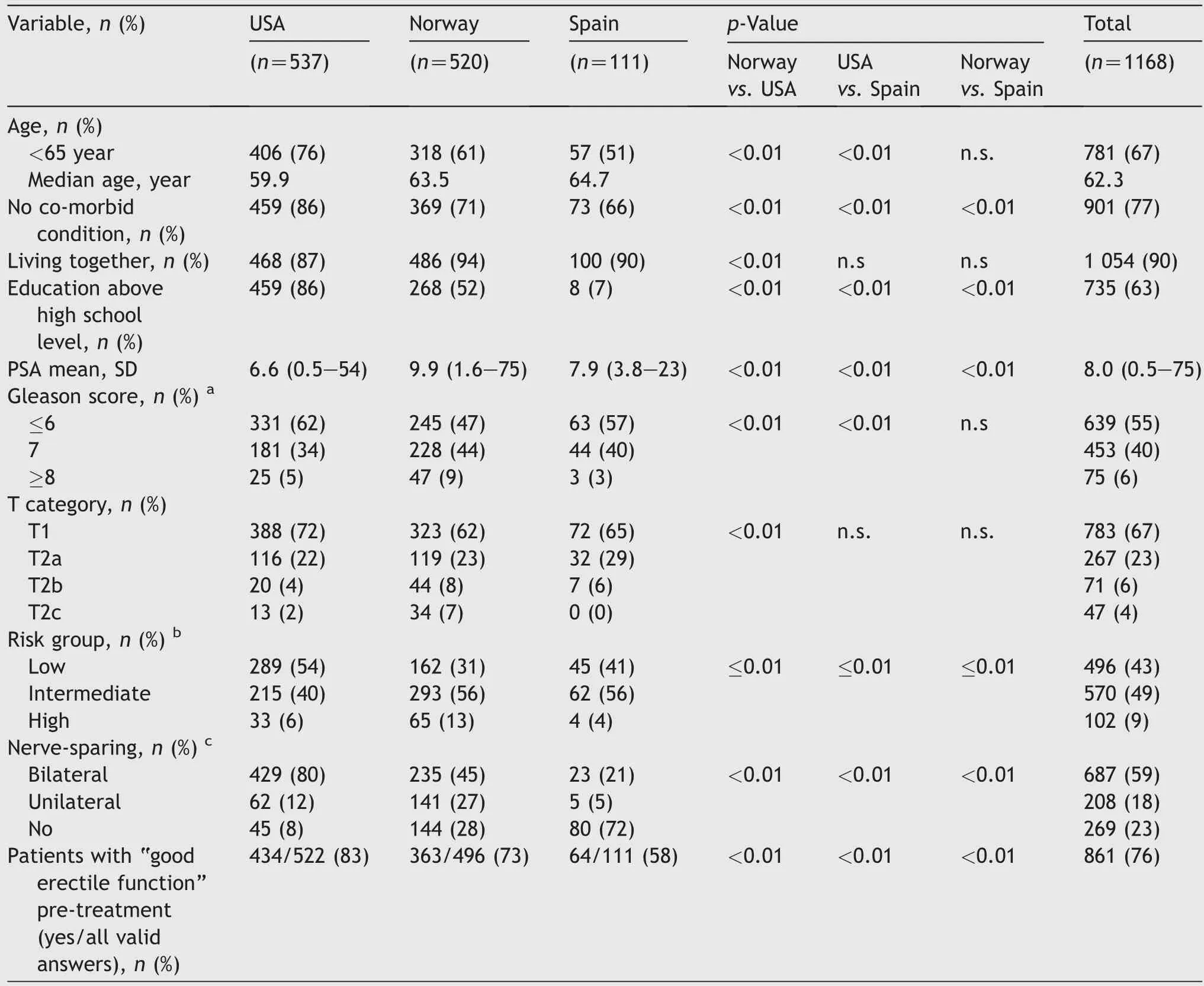

Compared to the Norwegian and Spanish patients, the American patients were younger, and fewer had comorbid conditions (Table 1). A higher proportion of the American patients had education above high school level and more had low risk tumors. Bilateral nerve-sparing RP was performed more often in the US material, and more of these had no erectile dysfunction before RP. Except for age, the values for all described variables were more favorable for the Norwegian than for the Spanish patients.

3.2. Urinary incontinence domain

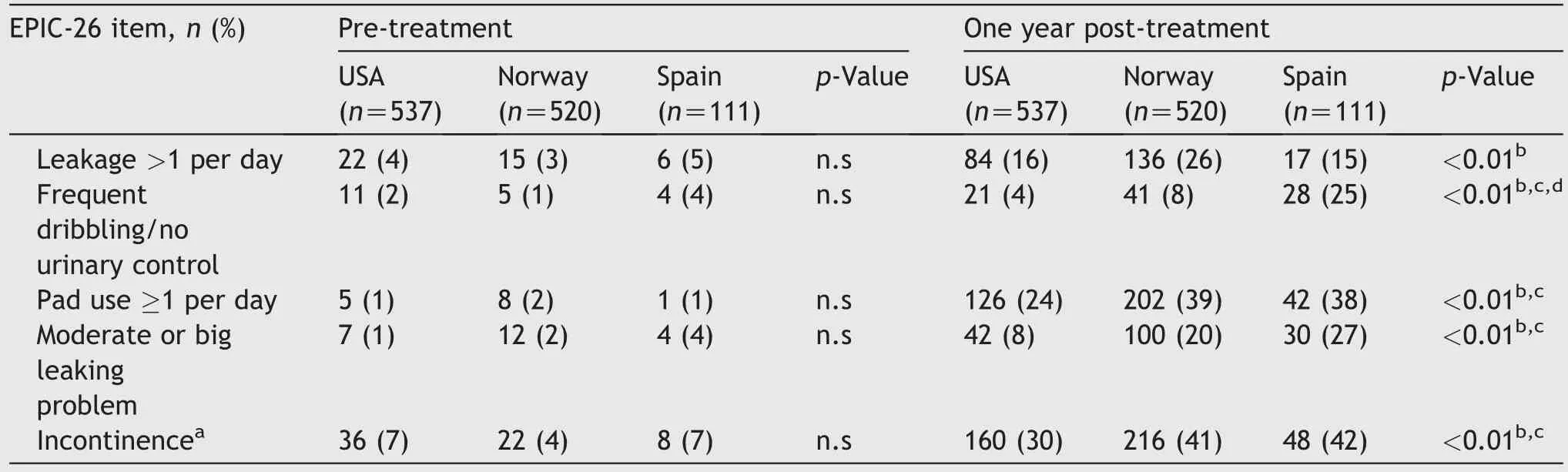

Before RP 66 men fulfilled at least one criterion for urinary incontinence with no significant inter-country differences (Table 2). However, 16% of the American, 31% of the Norwegian and 11% of the Spanish patients reported “occasional dribbling” preoperatively (data not shown)-most of them without use of pads. Overall only 2% of the men used pads and only 5% met the criteria for urinary incontinence. One year after treatment (Table 2)significant differences between American and both European groups emerged for all four criteria indicating urinary incontinence, with more favorable outcomes among the American than among the European men, in particular regarding pad use. At that time 40% of all American and Spanish patients and 66% of the Norwegian men reported “occasional dribbling”-most of them without pad use. Post-RP urinary incontinence was reported by respectively 30% of the American, 41% of the Norwegian and 42% of the Spanish patients, the difference being significant between the American and European patients (p<0.01). Except for “frequent dribbling”/“no urinary control” (p<0.01) the differences between Norwegian and Spanish patients were insignificant.

Table 1 Patient characteristics.

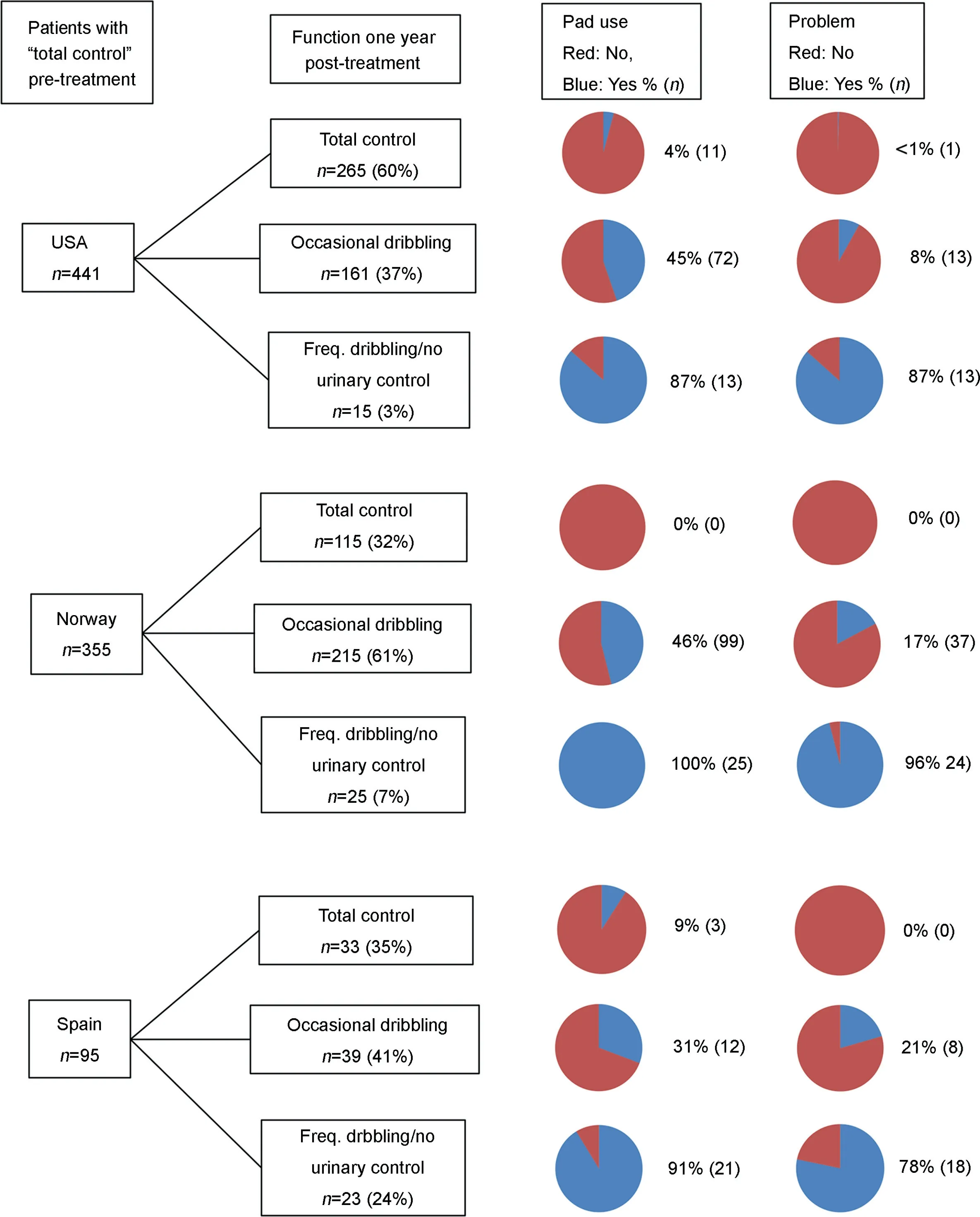

Overall, 35% of the American patients experienced any change from their pre-treatment level of urinary control compared to 50% of the Norwegian and 62% of the Spanish patients (Fig. 1). In most patients the change covered one step of decreased urinary control, most often the change from “total control” to “occasional dribbling”.

3.3. Urinary control, pad use and problem postprostatectomy for patients reporting“total control is included” pre-treatment

Fig.2 provides detailed information of the post-RP changes observed among 891 men with preoperative “total control”. Respectively 60% , 32% and 35% of the American,Norwegian and Spanish patients maintained total urinary control 1 year after RP. After RP, 96 of 441 American men(22% )compared to 157 of 450 European patients(35% )used at least one pad daily(p<0.001).The most frequent change was from“total control”to“occasional dribbling”reported by 37% , 61% and 41% of the men prostatectomized in the three countries. Within this leakage category the prevalence of pad use was similar in the American and Norwegian patients (about 50% ), but was only 31% in the Spanish cohort of only 12 patients. Inter-country differences emerged regarding problem experience, reported by respectively 8% , 17% and 21% of the American, Norwegian and Spanish patients (p<0.001 for the inter-continental difference).

Table 2 Dichotomized responses of the items in the urinary incontinence domain, pre-treatment and post-treatment.

3.4. Logistic regression analyses

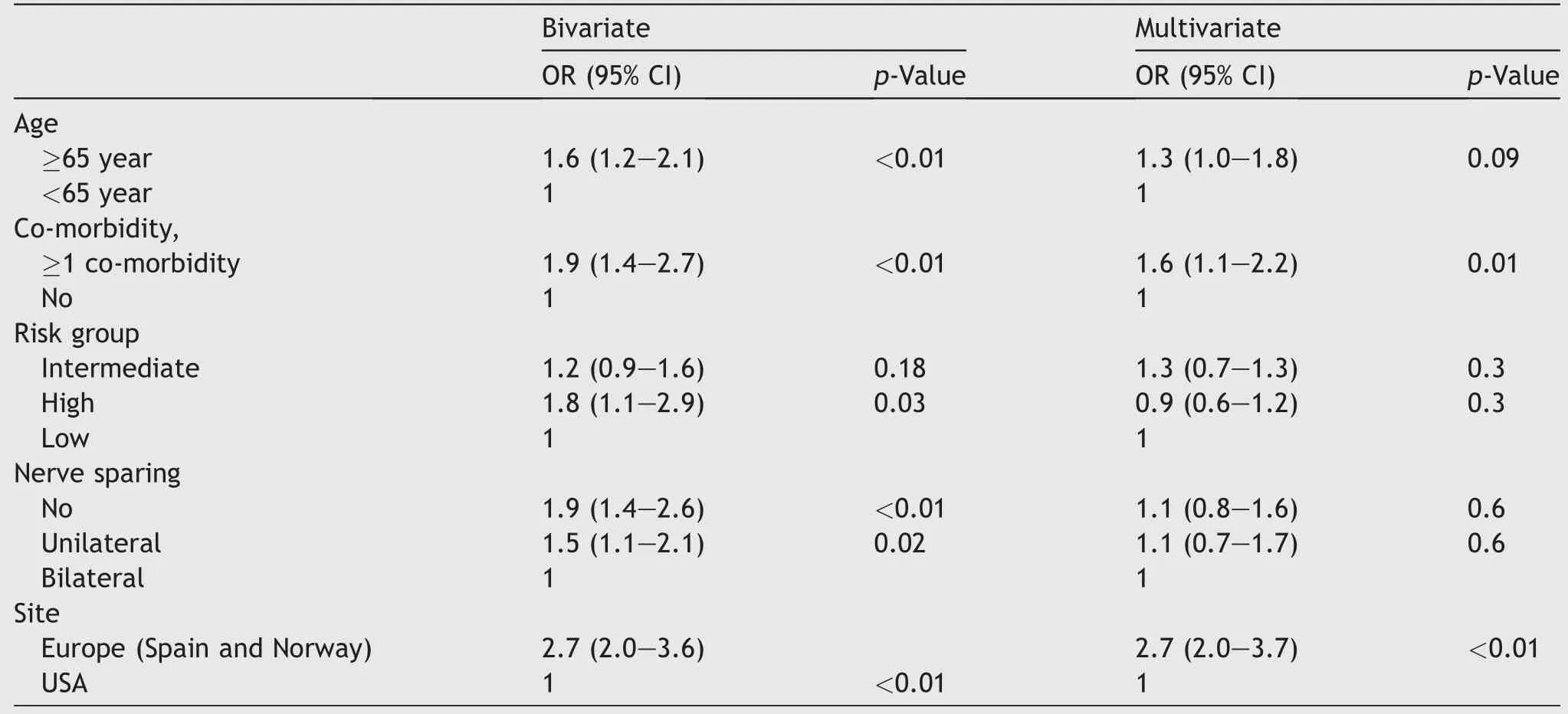

Table 3 shows ORs and 95% CIs from the bi-and multivariate analyses performed in patients with pre-treatment “total control”. In the bivariate analyses significantly higher ORs for not maintaining “total control” emerged for age ≥65 years, reporting comorbidity, the diagnosis of a high-risk tumor, omission of bilateral nerve-sparing RP and being operated in Europe (Norway or Spain). In the multivariate analysis being operated in Europe (Norway or Spain) and having at least one co-morbid condition remained the only significant factors for not maintaining “total control”. The risk of losing “total control” was about tripled for the European patients compared to the American patients(OR=2.7). In multivariate analysis with “pad use” and“urinary problem” being the dependent variables and adjusting for the same variables as mention above, the results were principally the same (data not shown).

Figure 1 Change in urinary control from pre-treatment to 1 year postoperative.(Steps of item 2 of EPIC-26:Total controloccasional dribbling-frequent dribbling-no urinary control).EPIC, expanded prostate cancer index composite-26.

4. Theory/calculation

Interpretation of inter-study results regarding post-RP urinary incontinence must be based on consideration of pretreatment variables and a valid assessment methodology.This study attempts to fulfill these requirements.

5. Discussion

5.1. Main findings

This study, based on pre- and post-RP data, is the first to compare self-reported 1-year postoperative urinary leakage between patients from USA and Europe. Importantly, the results are based on the internationally recommended and validated EPIC-26 questionnaire[10,17]and on definitions of urinary incontinence, which includes the use of only one pad per day(“safety pad”)[21].Before RP 5% of the patients were identified with urinary incontinence,without significant inter-country differences. After RP significantly fewer American than European patients met the criteria for urinary incontinence (30% vs. about 40% ),with occasional dribbling being the most frequent leakage category. Restricted to patients with preoperative total control and in a multivariate analysis adjusted for age, comorbidity and nerve-sparing operation technique, the risk of not retaining this leakage category after the RP was significantly increased among European compared to American patients.

Figure 2 Functional level,pad use and urinary problem 1 year after RP among 891 patients with total control pre-treatment.RP,radical prostatectomy; Freq, frequent.

5.2. EPIC-26

In this study we used the items of the urinary incontinence domain of the EPIC-26 questionnaire. This instrument was recently recommended for comparative evaluations of post-RP adverse effects [10] in an attempt to harmonize PCa patients’ report of dysfunction and bother from different studies. The urinary incontinence domain has shown satisfactory reliability and discriminative validity [16,19], but has never been validated against pad weighing as the “gold standard”. The international consensus group did not provide any guidelines for interpretation or definition of urinary incontinence based on EPIC-26. In this situation many clinical investigators,as also our group,use the dichotomization proposed by Sanda et al. [20] based on experience from 1 201 patients [14]. By use of this dichotomization, and in agreement with Namiki et al. [11] the greatest postoperative change of urinary control emerged regarding pad use for our patients from the three countries.However,much of our study’s post-RP inter-country variability remains unexplained, not at least regarding the need and prevalence of pad use within the “occasional dibbling”category. For example, before RP the overwhelming majority of Norwegian patients with occasional dribbling(31% )did not use pads, the comparable figure being 16% for men from USA. After RP about half of the American and Norwegian patients within this leakage category used pads, being classified as incontinent. Significant inter-continental differences were also revealed regarding problem experience in men reporting this degree of urinary leakage. These observations as to pad use and problem experience indicate that the“occasional dribbling category”in EPIC-26 is rather heterogeneous as to the true amount of leaking urine.

Following Sanda et al. [20] the proportion of pad-free patients 1 year after RP is in our study viewed as measure of post-RP urinary incontinence [21]. Admittedly, the shown variations as to“occasional dribbling”and the use of safety pad are possibly in part explained by non-identified differences for example cultural disparities, as discussed by Namiki et al.[13],Johnson et al.[22]and Lee et al.[23].On the other hand the availability of suitable protection aids can also play a role.

The criterion of pad-freedom seems thus to be too insensitive to indicate the true amount of urinary leakage.The performance of quantitative validation studies of EPIC-26 (pad-weighing among men with occasional dribbling) is required for increased understanding of the need and use of“safety pads”, the latter by many, but not all, clinicians viewed as expression of urinary continence [24,25].

Table 3 OR, 95% CI of not retaining “total control” 1 year post-treatment, bivariate and multivariate analysis. Only patients with “total control” pre-treatment were included.

5.3. Risk factors

In agreement with previous studies age, co-morbidity, riskgroup and nerve-aparing RP were in bivariate analyses associated with not retaining “total control” after RP,[6,8,26-29]. However, in part contrary to our hypothesis,and combining the two European countries, the site of RP persisted in the multivariate analysis as the highest risk factor for loss of total control whereas the role of nervesparing RP no longer was significant. Except for small numbers we can only speculate about possible reasons for this inter-continental risk difference such as the experience of the responsible urologist with the different techniques of nerve-sparing RP [30,31]. Less use of nerve-sparing techniques in the European counties(Table 1),probably related to delayed introduction explains in part our intercontinental risk difference. In addition, pre-RP variations of occasional dribbling (Table 1) and the previously demonstrated higher prevalence of sexual dysfunction among the European men within the collected samples[15]may have contributed to the higher risk of urinary leakage among the European patients as compared to the American patients [32].

5.4. Limitations and strengths

Our study has several limitations. First, except for age and co-morbidity,we do not have sufficient data to completely explain the shown inter-country risk differences. For example, no data were available regarding the intensity of pelvic floor training or postoperative complications. We do neither have data on type of intervention used in the individual patient(robotic or laparoscopic or open surgery)or the number of surgeons performing RP at each center.However,as far as we know,only minor,if any,differences of adverse outcomes are documented between the treatment modalities [6,8,32,33].

Second,in the current study we used pre-treatment and 1 year follow-up data.This postoperative time point may be considered“too early”.However,most,studies have shown little change in urinary function beyond 12 months[17,34-37]. Third, our non-randomized patients represent men operated between 2003 and 2010 with intra-prostatic tumors, with most American patients operated 3-4 years before the European ones. The results may be different today, with the increased experience with nerve-sparing procedures in the European countries. On the other hand,today’s increasing number of patients operated with highrisk prostate cancer may counteract the attempt to decrease urinary incontinence rates. Fourth, as discussed above, a more objective measure like pad-weight test would have provided objective measures. Finally, the low number of patients in the Spanish group did not always permit reasonable statements and comparisons for this country, therefore sometimes providing European vs.American findings.

The comparison of prospectively collected longitudinal pre- and post-RP data on patient-reported outcomes from three recognized international on co-urological research groups enabling analysis of changes is viewed as a strength,as few such comparative studies have been published so far. The use of the internationally recommended EPIC-26 questionnaire and its inherent we show challenges inherent to this instrument and its interpretation of the urinary incontinence when applied in an inter-country study warranting future validation studies.

6. Conclusion

One year after RP,patients from Europe(Spain and Norway)reported more unfavorable outcomes by EPIC-26 than the American patients to most of the urinary incontinence items, the difference remaining in the multivariate analysis. The response alternatives “occasional dribbling” and“≥1x pad use” of EPIC-26 should be validated with pad weighing as “gold standard”.

Author contributions

Data acquisition:Anne Holck Stors,Martin G.Sanda,Olatz Garin,Peter Chang,Dattatraya Patil,Catrina Crociani,Jose Francisco Suarez, Sophie D. Foss

Data analysis: Milada Cvancarova, Anne Holck Stors,Sophie D Foss

Drafting of manuscript:Anne Holck Stors,Sophie D Foss.

Critical revision of the manuscript: Anne Holck Stors,Martin G. Sanda, Olatz Garin, Peter Chang, Dattatraya Patil, Catrina Crociani, Jose Francisco Suarez, Sophie D.Foss, Milada Cvancarova, Jon Hvard Loge.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The PROSTQA Consortium includes contributions in cohort design, patient accrual and follow-up from the following investigators: Meredith Regan (Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA); Larry Hembroff and Douglas Roberts(Michigan State University,East Lansing,MI,USA);John T. Wei, Dan Hamstra, Rodney Dunn, Laurel Northouse and David Wood (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA);Eric A Klein and Jay Ciezki (Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland,OH, USA); Jeff Michalski and Gerald Andriole (Washington University,St.Louis,MO,USA);Mark Litwin and Chris Saigal(University of California-Los Angeles Medical Center, Los Angeles,CA,USA);Thomas Greenfield,PhD(Eneryville,CA,USA), Louis Pisters and Deborah Kuban (MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA); Howard Sandler (Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA); Jim Hu and Adam Kibel (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA,USA); Douglas Dahl and Anthony Zietman (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA); Peter Chang, Andrew Wagner, and Irving Kaplan (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA) and Martin G. Sanda (Emory,Atlanta, GA, USA).

We acknowledge PROSTQA Data Coordinating Center Project Management by Kyle Davis and Jill Hardy, MS(Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA), Erin Najuch and Jonathan Chipman (Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA), Dattatraya Patil, MBBS, MPH(Emory, Atlanta, GA, USA) and Catrina Crociani, MPH (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA), grant administration by Beth Doiron, BA (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA), and technical support from coordinators at each clinical site. We would like to thank the study participants. Without them this study would not be possible.

The study was funded by a grant from Health-Region South. East, Norway (No. 8324).

Asian Journal of Urology2020年2期

Asian Journal of Urology2020年2期

- Asian Journal of Urology的其它文章

- Robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy:How can we get better?

- Management of staghorn stones in special situations

- Preoperative imaging in staghorn calculi,planning and decision making in management of staghorn calculi

- Staghorn calculi: Understanding the paradigm shift in management

- Carcinoma bladder and sliding bladder hernia: Unusual association of paramount significance

- Total pelvic exenteration and a new model of diversion for giant primitive neuroectodermal tumor of prostate: A case report and review of the literature