Endoscopic management of biliary strictures post-liver transplantation

Ahmed Akhter,Patrick Pfau,Mark Benson,Anurag Soni,Deepak Gopal

Ahmed Akhter,Patrick Pfau,Mark Benson,Anurag Soni,Deepak Gopal,Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology,Department of Medicine,University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics,Madison,WI 53705,United States

Abstract

Key words: Liver transplantation; Endoscopic management; Anastomosis; Biliary strictures; Biliary balloon dilation; Biliary stents

INTRODUCTION

Biliary complications after liver transplantation (LT) is a known and significant cause of morbidity in LT recipients.The incidence of post-LT biliary complications is increasing due to increased volume of transplants and longer survival of LT recipients[1].It is estimated between 5%-35% of LT recipients have biliary complications[2,3].The incidence of complications can be attributed to various techniques of LT including the use of living and deceased cardiac donors,number of donor bile ducts used,and type of surgical anastomosis[4].Most often the donor liver and residual native bile duct are established in continuity with the creation of a choledochocholedochostomy[5,6].However,the presence of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) results in the creation of a hepaticojejunostomy.A roux limb is created and adds to the complexity of endoscopic management of biliary complications and may require the aid of a balloon assisted enteroscope for technical success[7].

There are a variety of biliary complications that can arise which include the development of anastomotic and non-anastomotic strictures (NAS),bile duct leaks,papillary stenosis,and presence of bile duct stones/casts.Diagnosis is usually made with a combination of non-invasive tests including liver chemistries,abdominal ultrasound,and cross-sectional imaging (computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography).It is important to consider non-obstructive causes of cholestasis including cellular rejection,drug induced cholestasis,or recurrence of primary disease as this may prevent a delay in therapeutic intervention.Advancements in endoscopic techniques and tools have allowed endoscopic management to be the preferred method to manage most biliary complications[8,9].Our review will focus on endoscopic management of biliary strictures that can arise after LT.

BILE DUCT STRICTURES

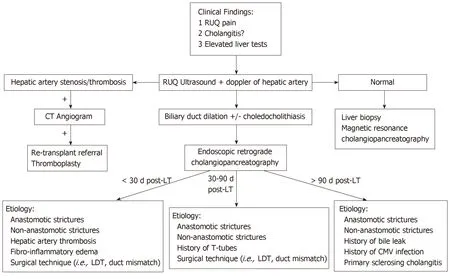

There are several risk factors that predispose to the development of bile duct strictures including hepatic artery thrombosis,donor after cardiac death,ABO incompatibility,preservation injury (cold and warm ischemia time),cytomegalovirus infection,duct mismatch between donor and recipient,presence of PSC,bile duct leaks,placement of T-tubes,and living donor transplantation (LDT)[10-15].Bile duct strictures can be noted early (< 30 d),delayed (30-90 d),or late (> 90 d) after LT[11,16](Figure 1).Early complications include hepatic artery thrombosis which can result in ductal stenosis and strictures as well as hepatic ischemia[5].Post-operative edema can also result in early ductal stenosis.Delayed and late complications can involve biliary obstruction at the anastomotic site or intrahepatic ducts due to ischemia[17].Bile leaks and recurrence of PSC are risk factors for the development of delayed/late bile duct strictures.T-tubes were previously used more frequently after LT to help maintain the reconstruction of the bile duct anastomosis.However,recent studies have found they may increase the risk of biliary complications including biliary strictures and may be more beneficial for select patients such as those who have a donor-recipient duct mismatch or a bile duct diameter < 7 mm[18,19].

LDT was first performed successfully in 1994 and has been steadily increasing due to limited supply of deceased donors[20].LDT has advantages over deceased donor transplantation (DDT) including reduction of cold ischemia time and improved graft viability[21,22].Nonetheless,there is a higher risk of biliary complications and specifically biliary strictures in LDTvsDDT (13%-32%vs5%-15%)[23-25].Incidence of biliary strictures in living donors' range between 0.5%-4%[26,27].LDT is presumed to carry a higher risk of biliary strictures due to the anastomosis of low-caliber and small ducts as well as increased number of donor ducts needed to establish biliary continuity[23].Bile duct strictures can be categorized as anastomotic or nonanastomotic with differences in endoscopic management and outcomes.

Figure 1 Evaluation of suspected bile duct strictures post-liver transplantation.

ANASTOMOTIC BILE DUCT STRICTURES

Anastomotic bile duct strictures (AS) occur in 5%-10% of patients within the first 12 mo of transplantation[28,29].However,they should always be considered in the setting of a cholestatic pattern of liver injury in LT recipients.As opposed to NAS,AS are segmental,shorter,and localized to the site of anastomosis[23,30].Bile leaks may be an independent risk factor for the development of an AS.An AS may form within 60 d after LT due to post-operative edema and fibro-inflammatory response along with transient ischemia[1,31,32].Strictures that form within the first 60 d respond well to 1-2 sessions of endoscopic dilation and plastic stent placement[1].

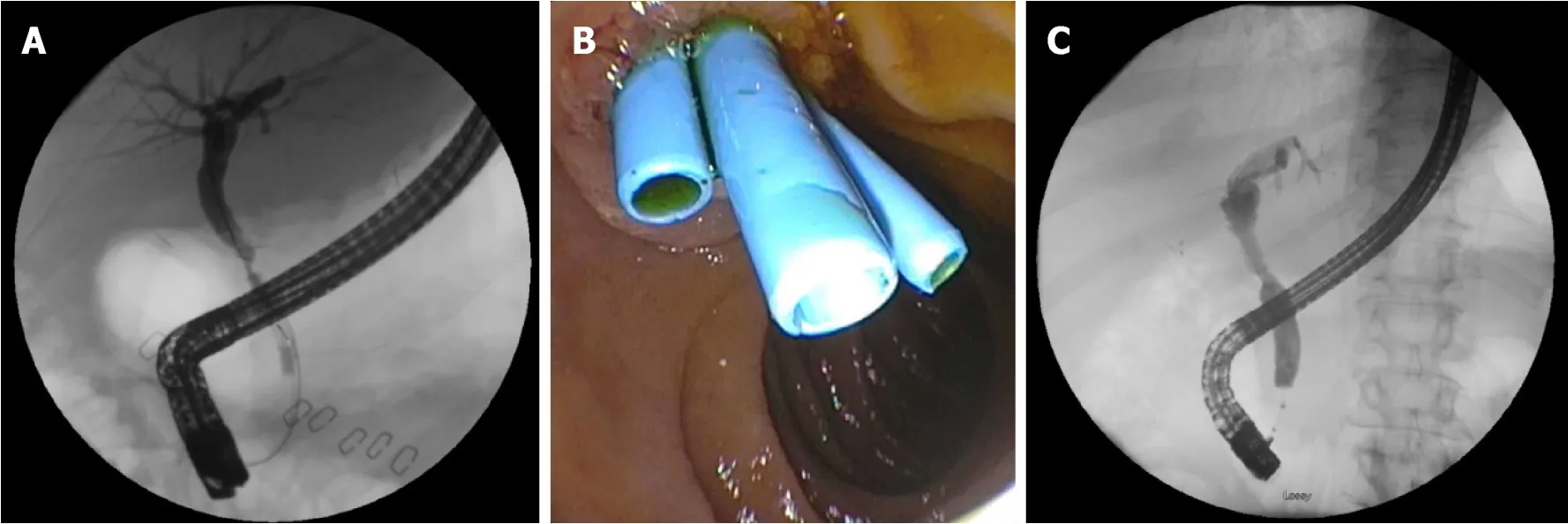

However,biliary strictures that form after 3 mo have a protracted course and require prolonged endoscopic sessions for adequate response.Endoscopic approaches for anastomotic strictures include balloon dilation,passage dilation with a Soehendra biliary dilation catheter,plastic biliary stents,and self-expandable metal stents(SEMS).A guidewire is used to cross the stricture and balloon dilators from 4-10 mm are used to dilate the anastomosis along with placement of 7 Fr to 11.5 Fr plastic stents bridging the anastomosis.The balloon size used to dilate is predicated upon the diameter of the donor bile duct.Soehendra dilators are useful in patients whom the anastomosis is severely stenosed and can be dilated from 4-10 Fr.In addition,balloon dilation is generally avoided in early strictures (< 3 mo) to avoid perforation or leaks of a recently constructed anastomosis.Most patients with an AS and those who present after 3 mo of LT,require several endoscopic sessions (3-5) for long-term success[28,33].The patency of most plastic biliary stents is 3 mo and thus,endoscopic sessions are performed at 8-12-wk intervals to prevent biliary obstruction[16].The preexisting stent is removed using a snare or forceps and a cholangiogram is performed to evaluate the patency of the anastomosis.There is no standardized bile duct diameter that corresponds to a clinically significant bile duct stenosis.However,cholangiogram features of a thin focal narrowing with proximal bile duct dilation along with evaluating the resistance encountered with anterograde and/or retrograde biliary balloon sweeps with an 8.5 mm or 11.5 mm biliary balloon across the anastomosis can help determine the patency of the anastomosis.In general,the goal is to dilate the anastomosis with larger sized dilators and in combination with increasing size or number of plastic biliary stents until patency is achieved and a waist is no longer seen (Figure 2).Combination of balloon dilation and biliary stenting have shown to be more effective than balloon dilation alone[34,35].Balloon dilation alone has a high recurrence rate of stricture formation when compared to balloon dilation and biliary stenting (62%vs31%)[35].LDT has lower success rates of stricture resolution compared to DDT despite similar techniques of balloon dilation plus plastic biliary stents (37%-71%vs75%-91%)[36-39].This may in part be explained due to the use of peripheral ducts and presence of smaller multiple anastomotic strictures[1].Resolution of anastomotic strictures are improved with multiple and maximum number of plastic biliary stents.Several studies evaluating anastomotic stricture resolution in LT recipients found resolution rates to range between 87%-100% with recurrence in 0%-18% of patients[32,40-43].Number of endoscopic sessions to achieve stricture resolution ranged between 3-4 with a complication rate of 1.5%-5%.Complications were primarily related to pancreatitis and cholangitis.

An alternative strategy is to place a SEMS to prevent or reduce the need for frequent ERCPs that is necessary in the setting of plastic biliary stenting.Covered metallic stents have been used as uncovered SEMS may not be able to be removed and may preclude surgical bile duct intervention.In addition,a metallic stent may lead to hyperplasia leading to the formation of sludge/stone formation proximal to the stent[1].The role of covered SEMS has yet to be precisely defined but can be useful because of their larger diameter (10 mm),longer patency,and ability to be removed.However,they are limited because of rates of stent migration (4%-38%).Several studies examining the utility of covered SEMS after LT found resolution rates of anastomotic strictures between 61%-83%[44-48].Recurrence rates were higher in those who received SEMS ranging between 7%-32%[44-49].A randomized trial evaluating covered SEMS and plastic biliary stents found in sub-group analysis of posttransplant patients resolution rates of 89%vs86% with 158 to 194 d till resolution respectively.Stricture recurrence was higher in the covered SEMS group and stent migration occurred more frequently in post-transplant AS compared to all other cases[50].To mitigate the risks of stent migration an alternative is to use partially covered SEMS or stents with special anchoring flanges and anti-migration waists[51].A systematic review of case series including 446 patients by Kaoet al[52]did not find SEMS to have a clear advantage over multiple plastic biliary stents in LT recipients but found stricture resolution was improved in those patients whom the stent duration was longer than 3 mo.A recent meta-analysis of four randomized controlled trials comparing plastic stents to fully covered SEMS found no difference between stricture resolution,stricture recurrence,and adverse events.However,those who received a metal stent did have fewer ERCPs performed as compared to those who had plastic stents[53].Currently,there is no standardized approach for endoscopic management of AS.The use of multiple plastic biliary stents with balloon dilation and fully covered SEMS can provide similar resolution rates of AS after LT with overall low risk of adverse events.

NAS

NAS of the bile ducts have an incidence of 5%-10% after LT[33,54,55].The definition of a NAS is the presence of stenosis > 5 mm away from the anastomosis and may be located within the intrahepatics,hilum,or anywhere else along the bile duct(including the recipient duct).In contrast to AS,NAS may be multiple and longer in length.Recurrent PSC in the allograft or vascular insufficiency may result in the development of NAS.Vascular ischemia secondary to hepatic artery thrombosis results in biliary destruction and warm and cold ischemia,donation after cardiac death,ABO incompatibility,and chronic rejection are also risk factors for the development of NAS[1,30].NAS tend to occur 3-6 mo after LT though as many as 50% of patients may develop NAS after the first-year post-transplant[54,56,57].

The principles regarding the management of NAS are similar to anastomotic strictures,however,the optimal protocol has not been established.Balloon dilation with placement of plastic biliary stents have shown to be helpful though with less success and longer time to resolution as compared to anastomotic strictures[33,58].Balloon dilation is often not as aggressive as in AS with 4-6 mm biliary balloons commonly used.Overall,resolution rates of NAS range between 50%-75% and are associated with worse graft survival[30,59].However,a study of 48 patients comparing balloon dilation alonevsballoon dilation and plastic biliary stents found a significant difference and improvement in stricture resolution in those who only underwent balloon dilation (91%vs31%)[60].This may in part be explained by most of these strictures being located extra-hepatic.

Figure 2 Anastomotic bile duct stricture managed with biliary stenting and balloon dilation.

Bile duct strictures involving the hilum and intrahepatics may be more challenging due to difficulty with traversing the stricture secondary to the small caliber of these ducts as well as tortuosity that may be encountered.Longer,fenestrated stents(Johlin),are flexible and can be used for intrahepatic strictures and allow for adequate drainageviamultiple side holes and interstent space[61].Covered metal stents have not been readily used as they may impede flow from surrounding bile ducts and potentially increase risk of cholangitis.

NAS may progress despite improvement in liver enzymes in up to two-third of patients[40,54].Progression of NAS is more common in patients who develop NAS within the first year after transplantation or who have recurrent cholangitis[57].Like AS endoscopic resolution rates for NAS in LDT is lower than in DDT 25%-33%vs50%-60% respectively[39,62].Currently there is no standard protocol for management of NAS.NAS are of varying complexity with intrahepatic and hilar strictures providing an especially unique challenge to the endoscopist which may require alternative approaches for access and therapeutic interventions to the bile duct.

ALTERNATIVE APPROACHES

Endoscopic methods may not be feasible due to surgical anatomy (bilio-enteric anastomosis),tortuosity and angulation of the bile duct,or severity and location of the stricture which prevents a guidewire or dilation devices to traverse the stricture.Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunosotomy or roux-en-Y gastric bypass require deep ERCP methods such as balloon-assisted enteroscopy,endoscopic ultrasonography-directed transgastric ERCP,or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC).A multicenter trial showed balloon assisted enteroscopy to be successful in two thirds of cases and in 88% of patients in whom the papilla is reached.Single or double balloon assisted enteroscopy may be an alternative before pursuing PTC or surgical alternatives[63].

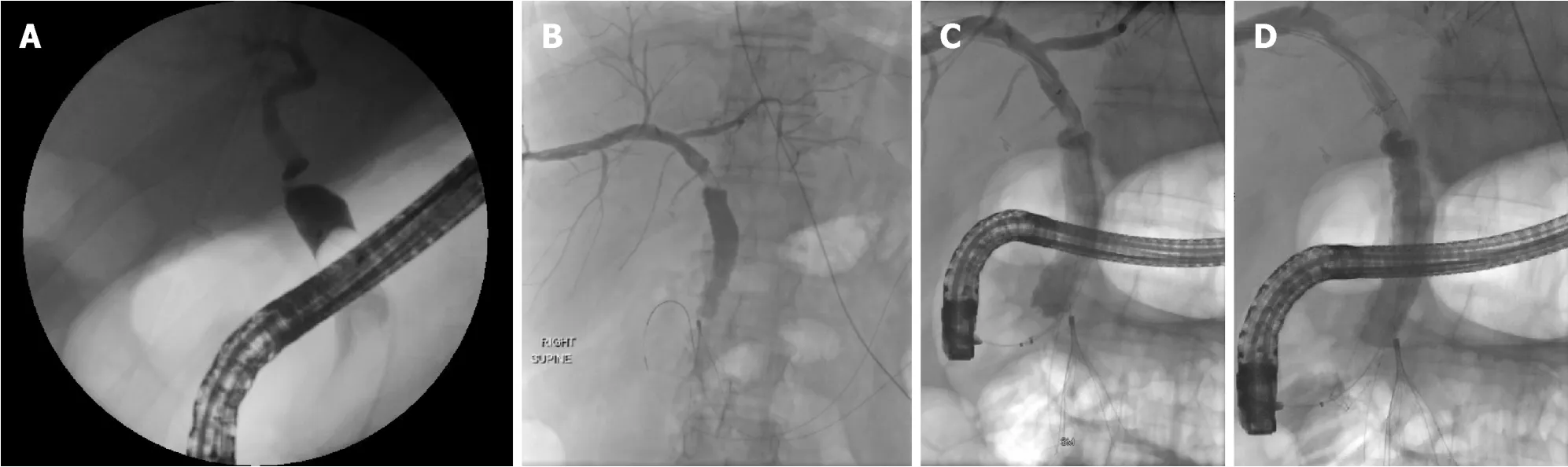

A rendezvous technique may also be used which combines PTC and an endoscopic transpapillary approach to access the bile duct and traverse the stricture that otherwise may have failed with conventional endoscopy (Figure 3).PTC in cases of benign bilio-enteric anastomotic strictures are reported to have an overall success rate of 80%[64].It is also especially helpful in those with intractable or multiple intrahepatic strictures as internal-external stents can be placed and relieve the obstruction.In addition,the potential of swing-tip cannulas in accessing tight intrahepatic strictures have been reported and may also help achieve faster cannulation of the bile duct[65,66].

Single-operator peroral cholangioscopy can also be used in the treatment of bile duct strictures by providing direct visualization of the lumen of the bile ducts.Direct visualization of the inside of the bile duct may help predict outcomes of endoscopic therapy based upon the pattern and severity of edema and inflammation seen[67].In addition,direct visualization can also be used in conjunction with the rendezvous technique to puncture the bile duct and safely traverse a completely obstructed duct[68,69].

Magnetic compression anastomosis (MCA) is a rescue technique used in the setting of complete biliary obstruction.A magnet is advanced to the site of the strictureviaERCP and another magnet is advanced percutaneouslyviaPTC.Fluoroscopy is used to properly align the magnets and a hole in the center of the magnets allow a guidewire to be advanced.Recanalization can be achievedviaPTC and serial biliary stenting can be performed.Magnet approximation and recanalization have been reported to be successful in 84% and 77% of patients respectively.MCA has been shown to be effective for short strictures (< 1 cm) with a low stricture recurrence rate[70,71].

Figure 3 Anastomotic bile duct stricture treated with rendezvous technique.

CONCLUSION

Biliary strictures play a significant role in morbidity of LT recipients.There exists a variety of techniques to approach anastomotic and NAS.However,despite the use of balloon and passage dilators along with plastic and metal stents,there is no standardized method to approach intrahepatic,hilar,or extra-hepatic bile duct strictures.In addition,patients with altered surgical anatomy and increasing use of LDT add to the complexity of providing successful outcomes.Nonetheless,endoscopic management of anastomotic and NAS are predominantly successful with relatively low complication rates.Further larger and comparative trials along with the advent of more endoscopic tools may allow for increasing rates of success and improved times till resolution of biliary strictures.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

John McDermott,Department of Radiology,University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics,Madison,WI 53719,United States.

World Journal of Meta-Analysis2019年4期

World Journal of Meta-Analysis2019年4期

- World Journal of Meta-Analysis的其它文章

- Drug interactions of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors involving CYP enzymes and P-gp efflux pump

- Anti-inflammatory properties of antidiabetic agents

- Effectiveness of taxanes over anthracyclines in neoadjuvant setting:A systematic-review and meta-analysis

- Safety and efficacy of percutaneous transhepatic balloon dilation in removing common bile duct stones:A systematic review

- Subcellular expression of maspin-from normal tissue to tumor cells