A new paradigm for assessment of infant feeding deviation

Ailsa Rothenbury

A new paradigm for assessment of infant feeding deviation

Ailsa Rothenbury

Normal child development is slow from birth to 25 years. Since Neolithic times, humans have relied on common sense, learned by trial and error, and mourned infants lost to infection and malnutrition. In recent times, knowledge of the process accelerated with increasing interest in child survival and health improvement. Historically, infant survival relied on breastfeeding until pathogens were identified, food technology developed, and infant/child surveillance commenced within the ethos of public health. Today, universal screening of infants from birth aims to identify deviation from the norm in all areas of development, allowing early intervention and correction. The personal experience of health professionals can be a positive factor in reflective practice, questioning orthodoxy and generating new perspectives and corrective strategies. Clinical settings generate practice-based evidence, a prerequisite for research. This concept of the infant as a primary cause of feeding problems demands consideration of a new paradigm and prompts research.

Assessment; suck-swallow-breathe cycle; normal development; practice-based evidence

Organizations must invest in the tools and skills needed to create a culture of evidence-based practices where questions are encouraged and systems are created to make it easy to do the right thing.Titler [1]

Introduction

Science has tested many assumptions, yet there can be problems associated with generating scientific evidence in practice. Titler [1] states it is no small challenge to move from "traditionbased to evidence-based care delivery" and identifies the failure of scientific findings to reach "communities in a timely fashion" as a system failure. However, when orthodox treatments are ineffective, clinical practice may demand an immediate innovative solution to the presenting problem. This frequently occurs in infant feeding in the community, when infant behaviors deviate from the expected normal path and there are associated maternal symptoms. Following discharge, medical care is diminished and community nursing care melds into health promotion, and intervention melds into parental domestic health practice.

Gordon [2] comments that as far as child survival was concerned, little changed between Neolithic times and the European industrial revolution. Infants received passive immunity to infectious disease directly from the mother: "it wasalmost a death sentence if the baby could not be raised on the breast – hence the popularity of wet nurses"[3]. In antiquity, wet nurses were responsible for birthing rituals and subsequent infant feeding. By the 17th century birthing rituals were community events [4]; changes in obstetrical technology started to reduce maternal and infant deaths during birth. In Britain, industrial cities became the norm in the 18th century, but citizens had little knowledge of how this increased risks of infectious disease, or the need for domestic hygiene. In this setting new approaches were needed and interest in public health and infant welfare developed.

Shifting from 'trial and error' to scientific inquiry

Breastfeeding remained essential for infant survival until advances in food technology saw the introduction of tinned and powdered milk and less dangerous milk. Valenze [5]describes the development of processed milks in the mid 1880s in America, Britain, and Russia. It was largely the American Civil War soldiers who popularized condensed milk, and it was some time before milk for babies captured a piece of the market. By 1900 a burgeoning market for condensed milk saw an increase in product weight from 38 million to 875 million pounds within a few years. New marketing practices were largely responsible for increased sales and consumption.Chemists, not pharmacists, initiated and developed these processes, hence the term infant 'formula.'

With the identification of microbes, domestic hygiene became important for disease control, reticulated water systems were built, engineers constructed sewers, and statisticians collected data. The public health discipline was gradually established and vital statistics were monitored. Increased understanding of the value of outcome measures improved the range of interventions used. The development of infant/child health surveillance was a major advance, a forerunner of preventative health and led to a reduction in disability. Infant anthropometry and record keeping contributed to the national health in Britain and the British Empire. Screening tests and attending to parent concerns in primary care remain important [6]. It was in this environment that the child welfare movement developed.

Natural to artificial infant feeding

In precolonial Australia where Aboriginals lived in small groups, the problems of postindustrial Britain did not exist.Donald Thomson, who photographed Australian Aboriginal families in Arnhem Land in 1935, stated that infant care practices had not changed since Neolithic times, when infants depended on maternal contact for warmth rather than fires.The infant was "either at her breast or sleeping in the sand beside her...[and] not weaned until four or five years old,unless another child is born" [7]. Family groups were mobile in gathering food, hunting, and collecting water; sewage treatment was nonexistent, accurate measurement did not exist,and the modern scientific method was unknown. Oral traditions passed cultural knowledge from respected female elders to younger women.

At the turn of 19th century, Sydney was an extremely unhygienic place. A British health surveyor was commissioned to establish a safe water supply for the colony. He did, but he also employed Lady Inspectors to visit new mothers at home,achieving an 84% increase in breastfeeding in the metropolitan area. The infant mortality rate dropped significantly, not because medical advancesper se, but because of the use of public health principles, monitoring, and data collection [2].This sowed the seeds for subsequent child surveillance by governments in the early 1920s.

At around this time in New Zealand, a new approach was developing after a physician's wife reportedly accused him of caring more about his animals than his adopted slow-growing daughter [8]. Truby King'sideaaffected multitudes of mothers and infants throughout the British Empire. A group of his New Zealand contemporaries, medical men with interests in animal husbandry, midwifery, and public health, incorporated scientific knowledge and training in developing the Plunket Society, a child welfare movement. There were contemporary medical claims that 75% of mothers could "not successfully suckle their infants," thus condoning bottle feeding as a rational feeding method. It is ironic that Truby King was remembered for his 'particular contribution' to New Zealand infant welfare for introducing American formula for babies,even though he held to his 1904 belief, that 'breast milk was best.' This 'scientific and accurate' mode of feeding became the norm throughout the British Empire, forming a basis for hands-on training of mothercraft and child health nurses until the 1970s, when tertiary courses commenced. Similar models existed in Canada and the United States with mutual sharing of information [8]. Any intervention was regarded as successful if infant symptoms resolved. The Plunket Society remains a national institution today, supporting breastfeeding and parenting practice.

Reclaiming the value of breastfeeding

During the 1960s in Australia, bottle feeding was ubiquitous,natural feeding had declined. The developing controversy was actually about method and content, not normal function, with average weight gain a successful outcome. Then as now, nurses and midwives 'encouraged women' to breastfeed [9], ignoring the obvious fact that it is the infant who milks the breast, while mother produces the milk. A Brisbane medico, Dr. C. Grulee used the comments of a long-experienced nurse to boost his public argument [9]: "Many doctors have considerable responsibility for the decline in breastfeeding, not so much because they deliberately wean the babies but because they will not help the mothers to persevere." Nurses were criticized for a tendency to recommend bottle feeding. Allied health therapies such as speech pathology and occupational health with roots in antiquity specialized in communication skills from around 1870, disregarding oral motor feeding skills in infants [10].

Some medicos were aware of problems with bottle feeding but apparently had no oral motor function concerns. In 1939 Cecily Williams gave a talk to Singapore Rotary and declared that "misguided propaganda on infant feeding should be punished as the most miserable form of sedition; these deaths should be regarded as murder." She was appointed as the first head of the Maternal and Child Health Division of the World Health Organization in 1948 [11]. The nutrition debate has continued for 100 years, distracting health professionals from examination of oral motor function as a cause of maternal and infant symptoms and premature weaning.

Breastfeeding promotion and advocacy

Nursing and midwifery skills provided the basis for my practice as a mother in 1971. During the 1970s, midwives did not instruct mothers on holding (now called positioning) their infant at the breast. The nursery provided a more sterile environment than the bedside, and babies had restricted four hourly access to their mothers. The benefits of skin-to-skin contact were yet to be recognized, and before the milk supply eventuated, babies were fed 5% glucose and water by bottle.

On day 4, feeds commenced at 3 min for each breast and gradually increased to 5 min and then 10 min – to allow the nipple to 'toughen up.' If nipples were traumatized, grazed,bleeding, or painful, this was seen as a maternal deficiency– for example, fair skin, feeding too long, and nipples not yet toughened up. The baby was never considered as the cause of the damage, even though commonsense standard therapy was to rest the nipples for 24 h, feed by bottle, then try again[12]. Care of premature infants was an acknowledged medical domain, with technology a vital component for survival– for example, intravenous fluids, nasogastric tubes, high protein feeds, minimal handling, and 24-h care and monitoring. Immature physiology was the rationale. If babies were inefficient in feeding, other coping strategies were used to ensure caloric intake: weight gain indicated the timing of transfer to bottle feeding, then breastfeeding.

Over time, I changed from a nurse taking specific medical orders to a mother with personal goals and an understanding that my unique experience was not always described in textbooks. Cultural lessons were gleaned in Papua New Guinea,where breastfeeding is commonplace without the accoutrements Western women believe essential [13]: maternity bras,breast pads, electric pumps, books by experts, how to videos,and so on. It was common and unremarkable if a woman other than the mother breastfed another baby; quite different from the case of expatriate women attending Nursing Mothers'Association of Australia meetings, where I was the first counselor and president [14]. The Health Department recognized the dangers of bottle feeding in a tropical preindustrial society of low literacy, unreliable domestic water, and nonexistent sewerage treatment. As health employees, we could confiscate feeding bottles, especially those shaped like teddy bears or astronauts, as a life-threatening technology. As president of NMAA in PNG I brought these bottles to the attention of the Minister for Health and the national newspaper.

Two decades after my nursing training, in 1986 I completed the International Board of Certified Lactation Consultants(IBCLC) examination, followed closely by the birth of my fifth child. Soon after, I was a lecturer at a tertiary institution in Perth, adding breastfeeding issues as the curriculum for normal child development allowed. As president of a subsequent nongovernment lactation organization, I could advocate breastfeeding in various situations, in 1995 becoming an inaugural member of the steering committee which aimed to correct maternity hospital policies which previously inhibited breastfeeding and inadvertently made bottle feeding the default method. As an educator and assessor for this Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI), I contributed to the accreditation of the first BFHI hospital in Western Australia(Joondalup) and later, on my own initiative, visited similarly accredited hospitals in Melbourne, Singapore, Glasgow,Dundee, and Edinburgh. In 2012, another opportunity took me to Thomayer Hospital in Prague, Czech Republic, where there were some 60 BFHI-accredited maternity hospitals.

The history and technology of infant feeding influenced my choice of dissertation topic for my master of arts degree[15]. It was this unique combination of tertiary qualifications, community counseling, and nursing experience which resulted in an invitation to represent Australia, in Washington,DC, United States, as a member of the 1998 IBCLC examination committee as a specialist on child development, as the United States does not have a nursing qualification like that of a maternal and child health nurse. Consulting texts and reviewing the literature was vital to ensure the examination was evidence based. It became a habit to seek evidence based answers to clinical puzzles, leading to a light globe moment,when I checked Sheridan's text again; 4 weeks "baby sucks well" [15]. Why did we not measure oral motor function along with the hips, eyes, weight, length, height, skin tone, and testes? My concept of a deviant infant gradually developed from the descriptions used by Sheridan.

Assessment of functional development in infants

Stein [6] indicates that pediatricians in the United States were and continue to be responsible for developmental assessment of infants at 9, 18, and 30 months. This is a gap in assessment for the newly discharged neonate, and as yet there remains "no established evidence base for specific ages when screening is recommended." In Australia and New Zealand, community and Plunket nurses, respectively, are trained in a surveillance role, providing a free service to all infants from birth to school age. The concept of 'normal range' is an important prompt to action, either towait and seeor refer immediately. Poorly considered referrals result in false positives, perhaps unnecessary treatment and poor use of any specialist's time. Sheridan [16]emphasizes that "mother's suspicions" are usually the first indication of deviant development, and that "it is not safe to rely upon a single examination." The concept of normal range is vital in deciding how long a deviation is monitored, when referral should be made, and to which health professional.

Parents read the popular press on child development, where often the 0–6-month age group is covered in one paragraph.The previously mentioned text "Children's developmental progress from birth to five years, the Stycar sequences" [17]reflects the work of many over some 35 years. It is detailed and helpful. However the four designated categories of posture/large movements, vision/fine motor, hearing/speech, and social behavior/spontaneous play do not mention oral motor function [17]. Newborns have several survival reflexes to aid feeding, and anecdotally, many believe that sucking, swallowing, and rooting reflexes are all that is required for successful feeding and that average weight reflects healthy progress.During the 1950 and 1960s Sheridan worked with bottle-fed,handicapped infants who required a medical diagnosis to establish the degree of handicap, and enable access to specialized health and education services.

Barnard and Twigg [18] recount stories of many mothers,driven by unhelpful suggestions from physicians and nurses,to develop associations providing mother-to-mother support:Le Leche League in the United States in 1956 and the Nursing Mothers' Association of Australia in 1964. The mothers felt that parenting and feeding decisions should be personal ones.These organizations aimed to reverse the contemporary public mind set that "feeding a baby was synonymous with bottles and breastfeeding rendered virtually invisible" [9]. Initially research was lacking, so group magazines reported personal anecdotes and then case studies, and eventually peer-reviewed journals developed as did conferences with international researchers and objective information. Medical advice had been challenged because of the mismatch between advice and actual experience – for example, my mother had been told to wean me at 9 months "because the milk is too weak," then in 1972, I was told "baby doesn't need it now, insufficient iron!."I knew from my child health nurse training that the iron in human milk was bioavailable and sufficient from 6 months with other foods [19]. Medicine lost some credibility, and mothers opted to treat themselves, using commonsense parenting, while persisting with demand feeding and seeking a better scientific rationale for action.

Evolution to technology

It is beyond the scope of this article to address the origins of human lactation in monotremes and marsupials: the platypus exudes milk directly onto the skin, and wallabies enhance the survival of their young by delaying and modifying lactation to suit the age of juveniles in the pouch. The complex evolution of human lactation is described by McClellan et al. [20], the various components of milk being both protective and nutritive.When technical options such as formula are used, the protective components are lost. The use of any technology in augmenting a natural process may be defined as sophisticated or deviant: reading glasses, walking stick, false teeth; technology is, however, a useful adjunct to a range of normal functions.Well-intentioned humans cannot fix every survival problem of infant mammals – for example, orphaned blue whales usually die. However, there has been success in Perth with an endangered marsupial, the numbat. Staff in this research program know it is a fruitless task if the neurological system is immature (i.e., the numbat has not yet developed fur). Jackson [21]describes the requirements for artificially feeding age-appropriate young: intravenous electrolyte replacement, 1–3-mL syringe, feeding tube, teat of appropriate size, a shot glass, a blindfold, and unique formula. Many of these items are needed for feeding premature human infants, where the developmental age may dictate survival.

As the new technology of obstetrics became popular in the 1700s I doubt there was an ethics approved study to test the hypothesis for use of forceps or for internal estimation of cervical dilation. But maternal and infant deaths were common,something needed to be done, so if the technology seemed to help, it was worth a try. Today obstetrics is considered a benefit, a natural corollary to deviation in the birth process. What of the baby where such technical assistance is used perhaps predisposing it to deviations in feeding and underdeveloped suckswallow-breathe (SSB) coordination? The complexity of this process is described in a prospective study by Goldfield et al.[22]. They note the potential for nipple confusion, hoping that principles derived from the study will contribute to improved methods of supplementation. A normal delivery should result in a normal infant who does not cause maternal symptoms.

In recent decades, normal postnatal hospital stay has significantly reduced; whereas in 1945 it was 14 days, in 2015 it is 1–3 days. Some medical practitioners suggest to parents that 38 weeks' gestation is full term, yet nerve development is consistent with 38 weeks. Normal lactation is usually around the fourth postnatal day, so it is difficult for a new mother to know first hand what she should expect. She may complain of nipple trauma within 24 h, and be told to keep feeding until the nipples toughen up, or to take the baby off the breast and feed it by bottle while the nipples heal. I am still looking for a scientific rationale of the physiology of tough nipples.

Maternal symptoms from the infant perspective

Eventually the following question formed: why has the mother got nipple trauma? What is the cause of the cause? In becoming an infant advocate and using an infant perspective, one can identify a different cause of feeding difficulty. For ease of discussion, from this point on maternal symptoms will be assumed to have been caused by an infant who has a deviation,usually muscle tightness and pain, oesophageal pain from gastric acidity, or the existence of lingual or labial frenulum [23].Normal development derives from normal anatomy and physiology, and the technological quick fix hides any biological basis for deviation. In a community setting, it helps to first examine the infant, then track back to maternal symptoms and reports.

When no problems are found during the discharge check,parents assume all is normal. At home, the baby should be observed to lie comfortably on both sides, head and face are symmetrical, there is no head tilt and cry in a conversational frequency range. Neck control is not achieved until about 2 months of age. The deviant infant will cause associated maternal symptoms:

? Head tilt, reduced oral gape, restricted tongue extension:traumatized nipples,pain.

? Inefficient SSB coordination:milk stasis,mastitis.

? Breast refusal, sleeping at breast, screaming:maternal anxiety,failing confidence.

Parents may describe infant behaviors which are not seen during a consultation, perhaps recording them on cell phones as photographs or sound recordings. The Neonatal Pain Policy from Royal Prince Alfred [24] hospital notes the infant's right to pain relief and the necessity of others to recognize, assess,and manage the infant's pain. Parents can use nonmedical strategies, massage, exercise, and repositioning before deciding something is not right, and resorting to analgesics or medications. The act of feeding is not intrinsically painful.

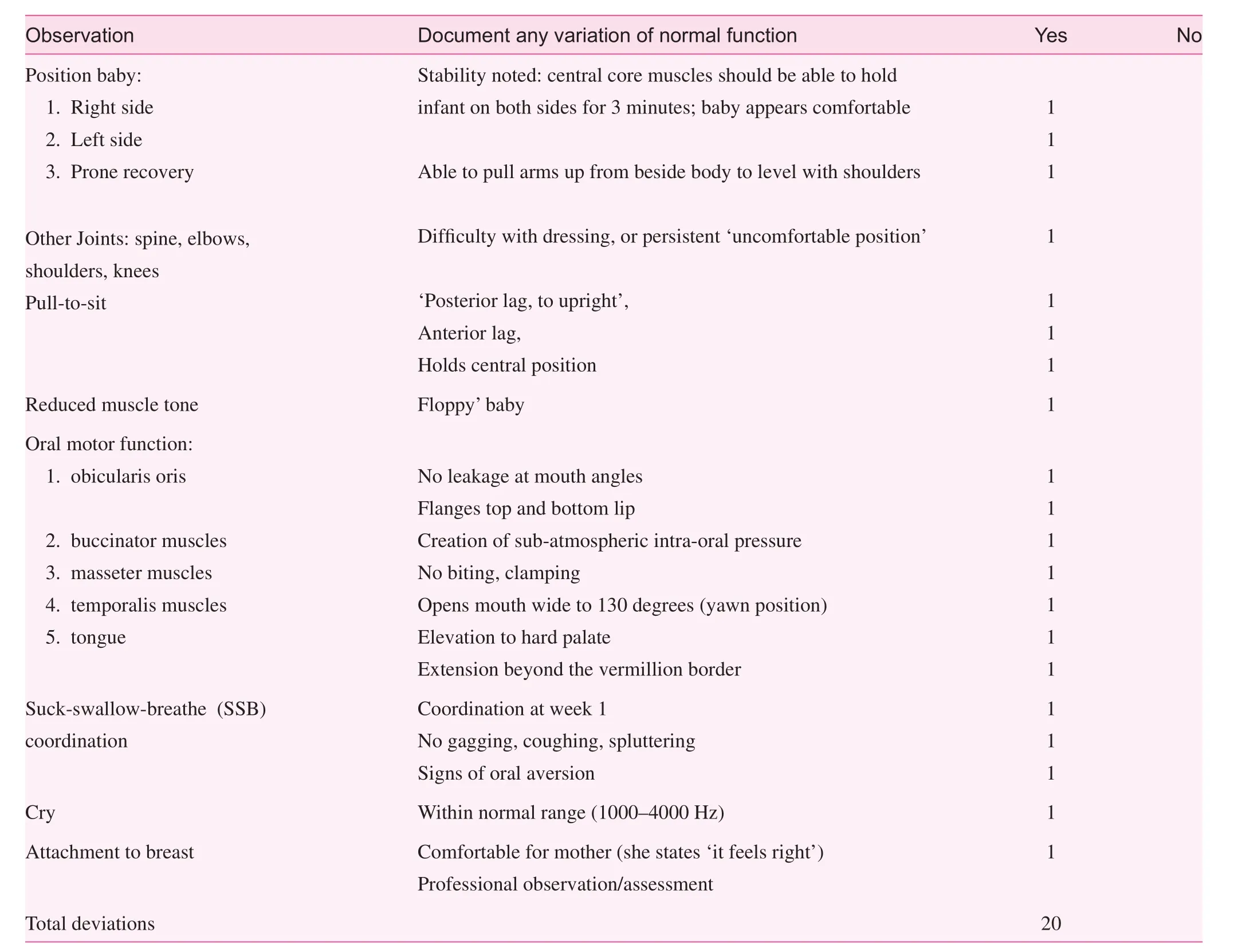

No validated assessment tools currently exist to objectively measure feeding efficiency. Over several years I developed a checklist to help myself be more objective, using information from parents and the literature in nursing premature infants and occupational therapy for stroke patients. By using Sheridan's 4-week marker of "baby feeds well," we can reason that this is a normal developmental milestone. However, other health professionals assume that 'feeding' relates only to solid foods from a spoon at around 4–6 months i.e. feeding skills(conversations with allied health professionals), appropriate referral is difficult due to lack of an approved referral pathway.When definitions are nonexistent or poor, objective measurement is difficult. Clinically, a simple assessment process helps clarify causes of infant discomfort and likely solutions. It is important that parents view the baby from a commonsense perspective and not be intimidated by any perception of superior health professionals' expertise in this nonmedical area.

Correction of deviations related to feeding

Any identified deviation requires correction or monitoring.Suck retraining is used on the principle of behavior-activated neuroplasticity [25]; when sensory input is correct, appropriate motor output is achieved. Using the checklist in Table 1,one can detect specific deviation and modify generic exercises for the individual. When head tilt exists, side-lying exercises use head weight against gravity as a corrective strategy. This is simple, cost-effective, and easy for either parent to do. When the SSB cycle is uncoordinated, suck retraining with modified finger feeding trains the baby [20, 26]. If gastric acid reflux is present, settling strategies are discussed, and if ankyloglossia or labial tie exists, the baby is referred to a pediatric dentist.Normal infant function is the goal, the feeding method is a parental choice. Today, health professionals do not receive specific training in bottle feeding, as happened in the 1960s,and many parents think that specific skills are not required.

When bottle feeding is used, the same principles of SSB apply;no leaking, clicking, or slurping. The list in Table 1 focuses on facial and central core muscles, SSB coordination, and maternal/infant comfort. It is a checklist, and any item found indicates a deviation and can be used after intervention to measure improvement. When infants demonstrate efficient feeding skills, maternal symptoms resolve. An instruction list was included in my 2009 book, in the "Parent coaches" chapter,but is best learned by supervised practice [27].

For too long feeding deviation has been detected by mothers, reported to health professionals, then ignored. If a health professional indicates that attachmentlooks good, but the mother insists that pain persists, it is a good indication that something is amiss. Weight trajectory is a useful indicator, but says nothing about normal development. Infant ability to coordinate SSB in the first week of life is a developmental task.Deviation which is not addressed before 3 months is difficult to correct. Consideration should be given to the National Health and Medical Research Council's (NHMRC) definition of prevention developmental surveillance and its indication that use of a process where we ask about parent concerns, attend to them, and make accurate observations will contribute to connection of the proverbial dots [28].

Clinical implications

Does this checklist (Table 1) meet the criteria for a screening test? In the NHMRC systematic review of screening and diagnosis tests [29], the Cochrane Methods Group indicated that screening involves "any measurement aimed at identifying individuals who could potentially benefit from intervention." If at the first contact, child health nurses checked for signs of oral motor deviation, many feeding difficulties could be averted.This would be an improvement on the reality of past decades when strict feeding regimes ruled, maternal pain was expected,weaning to formula and bottles by 6–8 weeks was unremarkable, and personal comments by health professionals were considered facts. The automatic use of a feeding bottle to increase nutrition does correct a physiological oral motor deviation.

If this paradigm of normal development is used in clinical practice, what screening tool should be used? The tools in current use in Western Australia – Ages and Stages Questionnaire(ASQ), Denver 11, and Parent Evaluation of DevelopmentalStatus (PEDS) – imply that they can be used from birth, but in their current form there is no item for oral motor assessment,indicating an identified gap in assessment. The National Health and Medical Research Council published a comprehensive review of evidence for and against developmental screening,stating that there is a case for less stringent expectations for test sensitivity and specificity [29]. Feeding difficulty can be an indicator of several medical conditions and rarely, I have in the past decade rarely found conditions where exercises and suck retraining were not effective (e.g., cerebral palsy,congenital dislocation of hip, fractured clavicle, upper motor neuron atrophy).

Table 1. Assessment of deviation in well full tern infants

Looking for more objective assessment, I developed a tool;the Australian Intra-oraL Suck Assessment (AILSA) as a simple objective method of conducting before and after assessment, attributing a score to efficiency of milk transfer from the milk container to the mouth. To date, this tool has been used effectively in everyday conditions, domestic and clinical;ethical requirements of the tool were considered, but validation is yet to occur. A mother seeking help is often at her wit's end and quickly warms to use of a relatively simple corrective strategy, where she can feel, see, and hear any improvement.

A lactation consultant assessment is quick, followed by supervision of the mother in the technique. The mother, being a coach for her baby, gets insight into how feeds will change at home, she has control over the situation, and can apply the principles as she sees fit. It may take 60 min to explain the causes of deviations, and how use of appropriate muscle activity will correct the deviation. Within 60–90 min, the most common feedback is: "Ah, now that makes sense." Fathers are often happy to be included in the process, especially if they have technical skills (e.g., a mechanic). The principles of a mechanical pump where a gasket is required to create a vacuum are the same as the principles for efficient oral motor function. Research is required to establish sensitivity and specificity for an oral motor assessment tool. All my attempts to undertake academic research have been fraught with difficulty and unsuccessful to date. The insights of practice-based evidence and a range of clinical experience have driven the search for solutions to this age-old problem. The quest for appropriate research methodology has been difficult because of the lack of evidence relating to specific IBCLC or child health nurse clinical practice.

Mothers have been trying to alert health professionals to problems of painful feeds for long enough. They have questioned much casual advice when it seemed unscientific or simply subjective. The World Health Organization's attempt to improve maternity hospital policies through the BFHI improved initiation rates but had little impact on feeding duration. Today mothers report that much advice received in maternity units echoes that given in 1945. It is time for a paradigm shift, for the infant to take center stage, and for deviations to be corrected.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

1. Titler MG. Nursing science and evidence-based practice. J Nurs Res 2011;33(3):291–5.

2. Gordon D. Health, sickness and society. St Lucia, Queensland:University of Queensland Press; 1976.

3. Porter R, editor. Patients and practitioners: lay perceptions of medicine in pre-industrial society. The Edinburgh Building,Cambridge, CB2 2RU, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1985.

4. Lounden I. Patients and practitioners. Lay perceptions of medicine in pre-industrial society. J Med Hist 1987;31(1):104–7.

5. Valenze D. Milk; a local and global history. New Haven &London: Yale University Press; 2011.

6. Stein M. Developmental surveillance and screening in primary care: a new AAP policy statement. J Watch 2007;5(11). Available from: www.medscape.com/viewarticle/550823.

7. Thomson D. Children of the wilderness. South Yarra, Victoria:Currey O'Neil Ross Ltd; 1983.

8. Bryder L. A voice for mothers: the Plunket society and infant welfare 1907–2000. Auckland, New Zealand: Auckland University Press, University of Auckland; 2003.

9. Barnard J, Twigg K. Nursing mums: a history of the Australian breastfeeding association 1964–2014. Malvern East, Victoria:Australian Breastfeeding Association; 2014. p. xv.

10. Duchan J. A history of speech-language pathology: overview.2011. Availbale from: www.acsu.buffalo.edu/~duchan/new_history/overview.html.

11. Knutson T. Breastfeeding pioneer: Cicely Williams. Le Leche League International (Asia); 2005 [Retrieved 2015 Oct 13].

12. Rothenbury A. Personal experiences during midwifery training at the North West Regional Hospital in Burnie, Tasmania; birth of 1st child at Royal North Shore Hospital in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia; birth of 2nd child at the Regional Hospital, Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea; 1969–1974.

13. Barnard J, Twigg K. Nursing mums: a history of the Australian breastfeeding association 1964–2014. Malvern East, Victoria:Australian Breastfeeding Association; 2014. p. 68.

14. Rothenbury A. Human lactation into the 21st century: a public policy issue or a lifestyle choice for parents? Perth, Western Australia: Murdoch University; 1992.

15. Sheridan M. Children's developmental progress from birth to five years: the Stycar sequences. Windsor, Berkshire, UK: NFER Publishing Company Ltd; 1973. p. 25.

16. Sheridan M. Children's developmental progress from birth to five years: the Stycar sequences. Windsor, Berkshire, UK: NFER Publishing Company Ltd; 1973. p. 16.

17. Sheridan M. Children's developmental progress from birth to five years: the Stycar sequences. Windsor, Berkshire, UK: NFER Publishing Company Ltd; 1973. p. 4.

18. Barnard J, Twigg K. Nursing mums: a history of the Australian Breastfeeding Association 1964–2014. Malvern East, Victoria:Australian Breastfeeding Association; 2014. p. 22.

19. Rothenbury A. Personal experience. Sydney, New South Wales,Australia, 1972.

20. McClellan HL, Miller SJ, Hartmann PE. Evolution of lactation:nutrition v. protection with reference to five mammalian species.Nutr Res Rev 2008;21:97–116.

21. Jackson S. Australian mammals: biology and captive management. Australia: CSIRO Publishing; 2007.

22. Goldfield EC, Richardson MJ, Lee KG, Margetts S. Co-ordination of sucking, swallowing and breathing and oxygen saturation during early infant breast-feeding and bottle-feeding. Pediatr Res 2006;60:450–5.

23. Rothenbury A. Parent teaching: correcting infant feeding diffi-culty in a community setting (poster). Presentated at International Society for Research into Human Milk and Lactation, University of Western Australia; 2008.

24. Royal Prince Alfred. Neonatal Pain Policy, 2001. Availbale from:www.slhd.nsw.gov.au/rpa/neonatal%5Ccontent/pdf/guidelines/pain.pdf.

25. Dunlop S. Activity-dependent plasticity: implications for recovery after spinal cord injury. Trends Neurosci 2008;31(8):410–8.

26. Oddy W, Glenn K. Implementing the baby friendly hospital initiative: the role of finger feeding. Breastfeeding Rev 2003;11(1):5–9.

27. Rothenbury A. Breastfeeding is not a spectator sport. Ailsa Rothenbury, Perth, Western Australia; 2009. p. 58.

28. Rothenbury A. Breastfeeding is not a spectator sport. Ailsa Rothenbury, Perth, Western Australia; 2009. p. 14, 38–52.

29. Centre for Community Child Health. Child health screening and surveillance: a critical review of the evidence. Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne for the National Health and Medical Research Council; 2002.

Ailsa Rothenbury 21c Bathurst Street, Dianella,WA 6059, Australia

E-mail: arothenbury@gmail.com

18 May 2015;

Accepted 18 August 2015

Family Medicine and Community Health2015年4期

Family Medicine and Community Health2015年4期

- Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- Current situation of AIDS prevention and control with traditional Chinese medicine and relevant policies in China

- Exploration and practice of general practitioner responsibility system in an urban community of Shanghai

- Family structure and support for the oldest old: A cross-sectional study in Dujiangyan, China

- Guest Editors' Prof le

- China's General Practice Conference highlights review

- The role of a community health service in the prevention of violence against women