Effects of Explicit Focus on Form on L2 Acquisition of EnglishPassive Construction

JI-YUNG JUNGZHAOHONG HAN

Teachers College, Columbia University, USATeachers College, Columbia University, USA

EffectsofExplicitFocusonFormonL2AcquisitionofEnglishPassiveConstruction

JI-YUNG JUNGZHAOHONG HAN

Teachers College, Columbia University, USATeachers College, Columbia University, USA

Intensive research on instructed second language acquisition (ISLA) over the last two decades has, overall, pointed to the usefulness of Focus on Form—a type of pedagogical intervention that engages learners’ metalinguistic attention in an otherwise meaning-based environment—in fostering learners’ communicative accuracy. A finer-grained understanding thereof has yet to be sought, especially vis-à-vis the type of focus on form and the nature of the target construction as potential mitigating variables. This small-scale study attempts to investigate the effectiveness ofexplicitFocuson Form (FonF) in the acquisition of the English passive construction. Two intact, lower-advanced level English-as-a-second-language (ESL) classes of a community English program in the U.S. participated in the study, with one serving as an experimental group and the other a control group. The study adopted a pretest, posttest, and delayed posttest design and spanned five weeks, including two weeks of treatment wherein the experimental group received eight mini-sessions of C-R and metalinguistic explanation, while the control group continued with their regular instruction. Results indicated that the treatment significantly facilitated the learning of the passive construction.

implicit/explicit focus on form, consciousness-raising, metalinguistic explanation, noticing, complexity

INTRODUCTION

The literature on instructed second language acquisition (ISLA) has, in the main, established that Focus on Form (FonF; Long, 1991)—a type of pedagogical intervention that engages learners’ metalinguistic attention in an otherwise meaning-based environment—facilitates second language (L2) development (e.g., Ellis, 2002a; Norris & Ortega, 2000, 2001; Spada & Tomita, 2010). Several questions have remained unclear, nonetheless. Which type of FonF is most beneficial to L2 learning? What types of knowledge follow from different types of FonF? Do the effects of FonF vary depending on the nature of the targeted construction? The last question, in particular, has drawn increasing attention in recent years. Extant empirical studies have yielded mixed results, but the thrust of the findings seems to be that implicit FonF, which makes no overt reference to rules or forms, is more effective than explicit FonF, which overtly engages learners’ metalinguistic attention, when the target grammatical construction is complex (e.g., Krashen, 1982; Reber, 1989). The jury is still out.

Recent ISLA research has witnessed a growing interest in explicit FonF, especially in its effectiveness promoting accuracy in adult L2 learners (e.g., Ellisetal., 2006; Lightbown & Spada, 1990; Rosa & Leow, 2004). Compared to child learners, adult learners, in general, have lower sensitivity to input, and, as a result, are less able to benefit from mere exposure to input (Han, 2004). It has thus been argued that L2 learners’ accuracy development should benefit from external facilitation of metalinguistic attention or explicit instruction (e.g., Hulstijn & Schmidt, 1994; Sharwood Smith, 1993). Schmidt (1990) claims that no learning can take place without ‘noticing’ or being aware of the target language (TL) input. But other researchers maintain that complex features are often not easily noticeable, especially in naturally occurring input or under implicit FonF conditions, in which case explicit FonF would be necessary, though ascertaining the effectiveness of explicit FonF on complex constructions would not be an easy undertaking. Contributing to the challenge of documenting the efficacy of explicit FonF on complex constructions are several factors. For one, there is not yet a uniform definition of complexity, as extant studies have demonstrated. Compounding the difficulty is, second, the need to tease out the effects of instruction from many of its potentially confounding variables, such as learners’ out-of-classroom exposure to the instructional target and learner differences in terms of prior experience and metalinguistic sensitivity. It is no wonder that to date researchers have generally shied away from embarking on studies to explore the instructional efficacy on simple versus complex constructions.

Small-scaled, the study reported in this paper was part of a larger attempt at understanding the relative effectiveness of explicit and implicit FonF on the learning of simple versus complex structures. Focusing on a putative complex construction, the English passive, we explored the effectiveness of explicit FonF in the forms of consciousness-raising activities and metalinguistic explanation. In the sections that follow, we will first provide a brief review of the relevant literature, highlighting gaps in the current understanding. After that, we will report the method and results of the study and discuss the main findings. We will conclude with a note on the limitations of the study and future directions.

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

ImplicitandExplicitFocusonForm

FonF, as originally proposed by Long (1991), involves an occasional shift in learners’ focal attention to formal linguistic properties as necessitated by the communicative demand of the task at hand. It is different from the traditionalfocusonformsapproach, which has as its goal the accumulation of individual, isolated linguistic forms irrelevant to the context. Somewhat different from Long’s conception, Doughty and Williams (1998) conceptualize FonF as a continuum of pedagogical options, ranging from unobtrusive to obtrusive procedures. Explicit or obtrusive FonF involves direct attention to form and grammatical rules, including rule explanation and overt correction, while implicit or unobtrusive FonF features absence thereof.

The present study explored the effectiveness of consciousness-raising (C-R), as an explicit FonF technique, in the learning of the English passive, a putatively complex construction. C-R is an intentional endeavor to draw learners’ attention to specific grammatical elements in order to improve learners’ grammatical competence (Rutherford & Sharwood Smith, 1985). As such, it is a loose approach with various instantiations of elaboration and explicitness. C-R differs significantly from conventional grammar activities as the former is essentially “concept forming” in orientation, whereas the latter is primarily “behavioral” requiring repeated production (Ellis, 2002b, p. 169).

Previous research has pointed to several factors that may influence the efficacy of FonF, in general, including the extent of instruction, outcome measure, learner characteristics, and the type or nature of the target grammatical construction. The latter has often been conceived of in terms of the level of complexity (e.g., Ellis, 2002b; Spada & Tomita, 2010), as further discussed next.

TheConceptofComplexity

Previous studies have appeared to vary considerably in how they define complexity, often, depending on whether the perspective taken is linguistic, psycholinguistic, pedagogical, or acquisitional.

From the linguistic perspective, complexity is viewed as having to do primarily with the formal or structural operations of a given construction. It concerns, therefore, such things as the number of transformations or rules involved in deriving the structure (White, 1991). In the psycholinguistic perspective, complexity is often defined in terms of processability constraints that determine the order of acquisition (Pienemann, 1989). The pedagogical perspective tends to associate complexity with the perceived ease or difficulty of learning a given construction (Robinson, 1996). An additional perspective on complexity comes from viewing it as determined by what is or is not ultimately acquirable (Han & Lew, 2012). Acquisition is, in turn, construed as a multi-dimensional and unitary process involving form, meaning, and use. The acquisitional perspective on complexity takes account of idiosyncrasy, thereby treating complexity as relative rather than universal.

EmpiricalStudies

To date there have only been a small number of studies, conducted in laboratory or classroom settings, that directly compare the relative effectiveness of implicit and explicit FonF on grammatical learning (e.g., Carroll & Swain, 1993; Murunoi, 2000) or examine whether either type of FonF facilitates it (e.g., Han, 2002; Philp, 2003). However, there have been several meta-analyses attempting to aggregate findings from an otherwise wide array of ISLA studies (e.g., Ellis, 2002a; Norris & Ortega, 2000, 2001; Spada & Tomita, 2010). Together, both the primary and the secondary research have yielded mixed findings. The present understanding seems to be that both types of FonF, explicit and implicit, can be beneficial to L2 development, but that their effects are modulated by learner internal and external variables, including the nature of the target construction in question.

Previous research has, usefully, revealed that implicit FonF generally has a positive, albeit tardy, effect on learning (e.g., Leeman, 2003; Mackey & Goo, 2007). Several studies have shown that complex constructions or constructions governed by probabilistic rather than categorical rules are better learned implicitly, in a meaning-based environment (DeKeyser, 1995; Krashen, 1982; Reber, 1989; Sorace, 2005).

Explicit FonF has also been found beneficial, sometimes more beneficial than implicit FonF (e.g., Carroll & Swain, 1993; Ellisetal., 2006; Rosa & Leow, 2004), yet its effects appear to be limited to the learning of simple constructions or constructions governed by categorical rules (e.g., Spada,etal., & White, 2005; Williams & Evans, 1998). In addition, it has been noted that explicit FonF is quick at inducing learning but falls short of retaining it (Gass & Selinker, 2008).

Recent ISLA research appears to underscore the need for explicit FonF, suggesting that it is capable of efficiently getting adult learners to drop non-target-like forms and start using target-like forms (e.g., Doughty, 1991; Fotos & Ellis, 1991; Spada & Lightbown, 1993). But the fundamental argument for explicit FonF has been that, due to maturational constraints and native language influence, adult L2 learners, in general, have low sensitivity to input and hence a weak ability to benefit from mere exposure to input (Han, 2004; Long, 2014). Ellis (2008) claims that what can be acquired implicitly is “typically quite limited” among adult L2 learners, without “additional resources of consciousness and explicit learning” (p. 119). Many have even gone so far as to state that what can be learned implicitly are simple morpho-syntactic structures, and the learning of complex structures has to rely on explicit FonF (e.g., Carrolletal., & Swain, 1992; De Graaff, 1997; DeKeyser, 1995; Gassetal., 2003; Hulstijn & De Graaff, 1994; Schmidt, 1990). A more detailed review of select studies follows.

Experimenting witheXperanto, an artificial language, as the target language, De Graaff (1997) found a significantly facilitative effect of computer-assisted explicit FonF on the acquisition of complex syntactic, complex morphological, simple syntactic, and simple morphological structures. Where the two syntactic structures are concerned, explicit instruction seemed more effective for the complex than for the simple structure, as revealed by the grammaticality judgment, gap-filling, vocabulary translation, and sentence correction tasks.

Similarly, in a lab setting, using a computer to mediate instruction, Robinson (1996) compared the effects of four different learning conditions—implicit, incidental, rule search, and metalinguistic explanation—on the acquisition of English pseudo-clefts and subject-verb inversion. Based on the number of derivations needed to produce a correct form, the former was judged a more complex structure than the latter. Measured by the speed and accuracy of grammaticality judgments, the metalinguistic or explicit FonF condition was, reportedly, significantly more conducive to the learning of subject-verb inversion than the other three conditions. It also seemed more facilitative of the learning of pseudo-clefts when compared to the other three conditions, though the difference did not reach significance. Thus, unlike the De Graff (1997) study where explicit FonF emerged as the ideal strategy for teaching complex structures, the Robinson study yielded less clear-cut findings, insofar as explicit FonF was seen as beneficial for the learning of both simple and complex structures, with greater impact on the simple than on the complex.

Studies conducted in classroom settings have, likewise, displayed a mixed bag of results. Defining complexity in terms of abstractness and first language (L1) and L2 difference, Gassetal. (2003) found that explicit FonF, operationalized into rule explanations plus provision of exemplars, was the most effective for learning Italian question formation, which was considered the most abstract and complex, less effective for Italian pronouns, and least effective for Italian vocabulary items, which was considered the most “isolatable” (p. 508) and least complex. However, the opposite was found in the implicit FonF condition involving only exposure to input: Implicit FonF was most beneficial for the lexicon, the least complex, but least beneficial for syntax, the most complex.

Such, however, was not the finding of another study. Comparing the effects of recasts and metalinguistic explanation on developmentally early and late features, one instantiating implicit FonF and the other explicit FonF, Varnosfadrani and Basturkmen (2009) reported that the developmentally early—presumably simple—features such as English definite articles, irregular past tense, and plural -swere better learned explicitly, whereas developmentally late—presumably complex—features such as English indefinite articles, regular past tense, relative clauses, active/passive voice, third person singular -swere better learned implicitly.

Complicating the general picture further, in yet another study, Housen, Pierrard, and Van Daele (2005), explicit FonF, operationalized as C-R (consciousness raising) with additional pedagogical rule explanations, was found to have similarly facilitated the learning of both complex (the French passive) and simple structures (the French negation). The complexity of the target structures was determined on the grounds of their structural and psycholinguistic properties. Furthermore, the instructional benefit was more pronounced in the participants’ unplanned than their planned oral production, suggesting, at least, that explicit FonF promoted implicit knowledge as much as explicit knowledge.

Williams and Evans (1998) compared the effects of recasts (i.e., implicit FonF) and metalinguistic rule explanation (i.e., explicit FonF) on the English passive and participial adjectives. Adopting both pedagogic and linguistic definitions of complexity, the English passive construction was taken to be more complex than participial adjectives. Results showed, overall, no noticeable difference in the effects of implicit versus explicit FonF on the learning of the passive construction. However, a closer inspection of the results from two of the measurement tasks, open-ended sentence completion and oral narration, revealed that explicit FonF produced substantial, albeit statistically insignificant, variance between the explicit and the implicit groups. On two other tasks, grammaticality judgment and close-ended sentence completion, explicit FonF had a significant effect on participial adjectives, the putatively less complex target feature. Taken at their abstract, these findings directly conflict with those from the Gassetal. (2003) study.

In a study involving younger learners, Spadaetal. (2005) engaged Francophone children in a variety of games followed by metalinguistic explanation over four weeks, three times a week. The targeted structures were English third person singular possessive determinershisandherand question formation. The latter was deemed more complex than the former, based on whether, and if so, how much, derivation is involved in each structure, as well as French-English crosslinguistic conceptual differences. From the participants’ overall performance on the grammaticality judgment, and oral and written production tasks, it appeared that the explicit FonF produced slightly better results for the acquisition of possessive determiners than for question formation. The pendulum, thus, swings back to supporting explicit FonF and its efficacy for simple rather than complex structures (cf. Gassetal., 2003).

In sum, the studies so far have not yielded conclusive findings regarding the effectiveness of explicit FonF in learning either simple or complex constructions. This is, in part, due to a lack of uniformity in defining what is simple or complex. Most of the studies seem to have based their decisions solely on the formal properties of the constructions in question, and, therefore, defined complexity purely from a linguistic perspective. The studies varied in their settings too—laboratory or classroom—where instruction was delivered by a researcher, teacher or computer. In addition, the studies differed in how they operationalized explicit FonF. The C-R activities in Housenetal. (2005), for instance, looked rather likefocusonforms, in that the treatment began with an emphasis on metalinguistic explanations. Last but not least, the outcome measures employed by the studies were dissimilar, some using grammaticality judgment (e.g., Gassetal., 2003; Robinson, 1996) while others additionally included free production (e.g., Spadaetal., 2005; Williams & Evans, 1998). And so forth.

Against this backdrop of a continued lack of understanding of the efficacy of explicit FonF for simple versus complex grammatical constructions, the present study made an exploratory attempt to understand how explicit FonF might affect the learning of a putatively complex construction, the English passive (Williams & Evans, 1998). Results from the study were meant to inform a fuller and larger scale study to follow. The questions that guided this small-scale study were as follows:

a. What are the effects of explicit FonF on the learning of the English passive construction?

b. Does explicit FonF increase accuracy in L2 learners’ knowledge and use of the English passive?

c. If so, are the effects durable?

In light of extant research, we hypothesized that explicit FonF in the form of intensive C-R would engender significant improvement in learners’ knowledge and use of the English passive.

METHOD

Participants

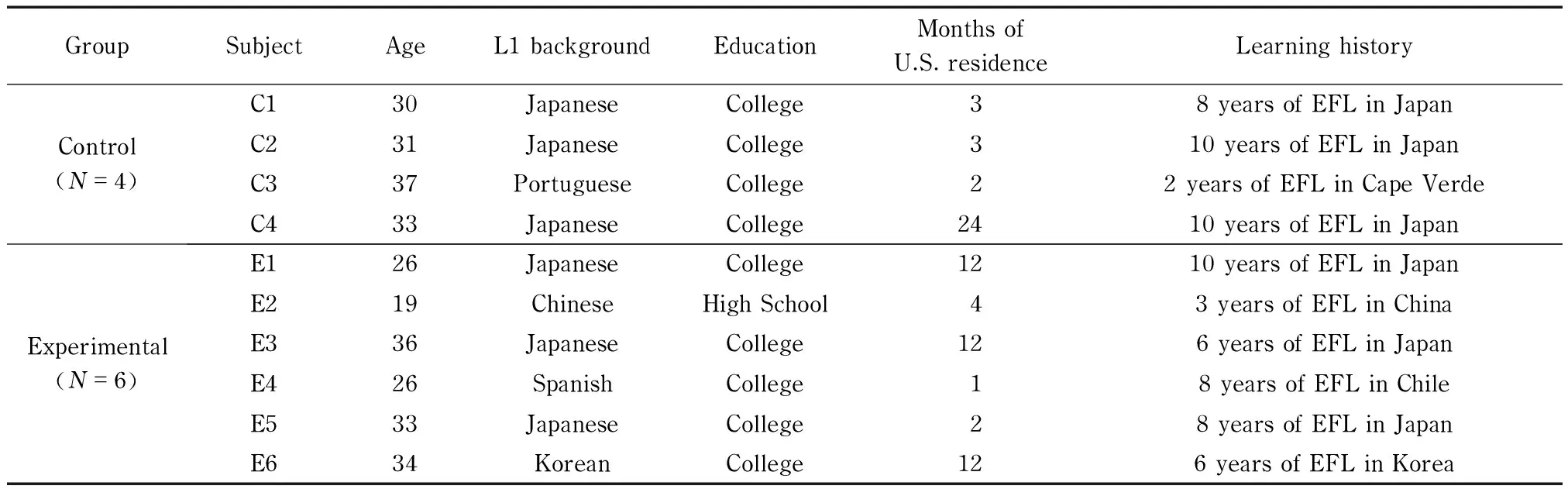

Two intact, lower-advanced level English-as-a-second-language (ESL) classes of a community English program in the U.S. were chosen as the site of the study. Participants were 10 adult learners, four of whom were assigned to a control group, and six assigned to an experimental group. They came from diverse L1 backgrounds—Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Portuguese, or Spanish—and had varying lengths of residence in the U.S., ranging from two months to a year (Table 1). All 10 participants had received similar, grammar-based English-as-a foreign language (EFL) instruction in their home countries. Pretest scores (see Table 2, 3, and 4) indicated they variously had partial knowledge of the target construction, the English passive, at the onset of the study. All reported a high level of motivation for learning English.

Table 1 The biographic information of participants (N=10)

TheTargetConstruction

The English passive was chosen as the linguistic target of the study, for its alleged linguistic, psycholinguistic, and acquisitional complexities (cf. William & Evans, 1998). First, this grammatical structure is governed by a set of syntactic and morphological rules: Among others things, the internal argument of the verb must be placed in the subject position of the sentence; different predicate configurations (e.g.,be+the main verb realized in its past participle form) must be employed to convey different temporal, aspect, and number meanings; and the agents of the action, if overtly expressed, must be enacted through aby-phrase in the post-verbal position (Le Coq, 1944). The passive structure poses a high level of psycholinguistic complexity, especially when used with varying tense and aspect. In order to successfully acquire the structure, learners need to understand and process the agent-argument relationships and different temporal references such as the point of speech, point of event, and point of reference (Reichenbach, 1947). Above all, the construction is developmentally late (Han, 2000; Spinner, 2011), and, therefore, acquisionally complex, the acquisition of which entails integral knowledge of its form, meaning, and discourse function (Han & Lew, 2012, p. 196). Pretest results have indicated that although the participants had some familiarity with the formal properties of the construction, they fell short of understanding when and where to use it.

Procedure

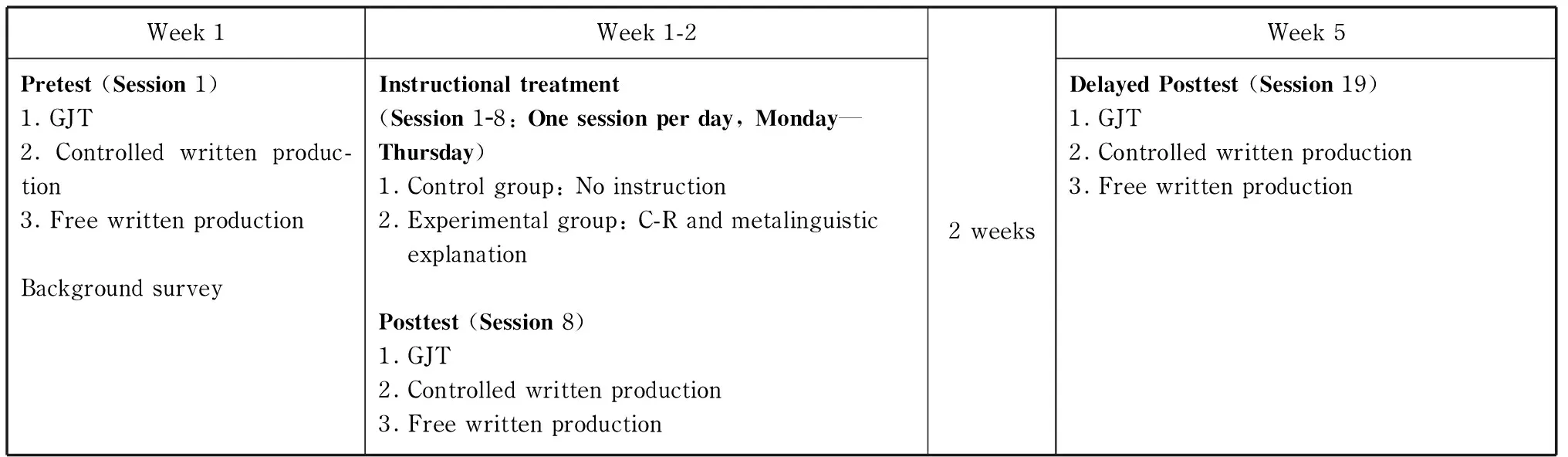

The study employed a pretest, posttest, and delayed posttest design over a span of five weeks (see Figure 1). The experimental group received explicit FonF on the English passive during a two-week period, while the control group did not receive such instruction. Both the experimental and control groups met four days a week, Monday through Thursday, for one session a day of two and a half hours. On the first day of the study, all participants took a battery of pretests, consisting of a grammaticality judgment task (GJT), a controlled written production task, and a free written production task, to display their initial knowledge of the target structure. In addition, the participants each filled out a biographic background questionnaire. During the treatment period, the experimental group received eight mini-sessions of instruction where they engaged in C-R tasks and were given metalinguistic explanations, while the control group continued with their regular instruction. An immediate posttest—with tasks comparable to those of the pretest—was administered to all the participants right after the last session to see if any noticeable changes had occurred in their knowledge and use of the target construction. A delayed posttest comparable to the pretest and immediate posttest was, then, conducted two weeks later to see if the changes (or lack thereof) observed on the immediate posttest were retained.

Figure1 Design of the Study

Materials

Four written texts were used during the treatment. Two of them, titledGeorgeZambelliFireworkEntertainment(see Figure 2) andAGoodLimousineDriver, came verbatim from the participants’ textbook,InCharge1, both texts within 120 words. The other two texts were adapted from the scripts of sitcomFriends, S5E9TheOnewithRoss’sSandwichand S9E6TheOnewiththeMaleNanny, each containing about 200 words.

Figure2 A Sample Text

Treatment

During the two-week treatment period, the experimental group engaged in four C-R tasks, each of which was administered every other day (Monday and Wednesday) and took about 30 minutes to complete. On Tuesday and Thursday, the participants received 10 to 20 minutes of additional metalinguistic rule explanations on either the formation of the passive construction or its tense and aspect configurations. The treatment proceeded as follows:

1. Reading the assigned text individually

2. Discussing the content with peers, guided by the given questions (e.g.,HowdidRossreactwhenhefoundthathissandwichhadalreadybeeneaten?)

3. Identifying and underlining the instances of the target construction in the text

4. Answering questions about the form, meaning, and function of the identified instances (e.g.,Whatisthepurposeofusing(1)passivevoiceand(2)pastperfecttensein‘Rossfoundthathissandwichhadalreadybeeneaten’?Wouldtheuseofactivevoicechangethemeaningofthesentence?)

5. Checking and discussing the answers with peers

6. Receiving metalinguistic explanation: Using Power Point slides, the instructor provided 10-15 minutes of instruction on the rules (e.g., word order, past particles, time lines, etc.)

7. Performing error correction activities: Participants were asked to correct errors in a paragraph adapted from the treatment text.

MeasuresGrammaticalityJudgmentTask(GJT)

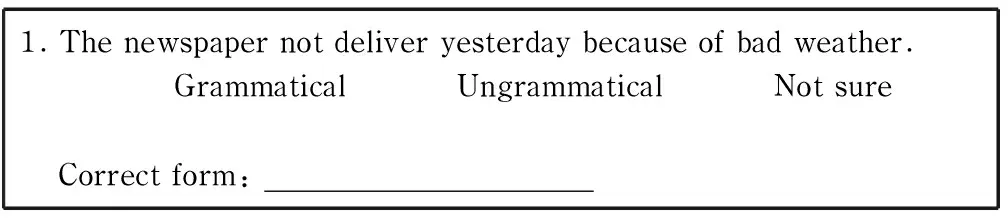

Three versions of a GJT were created for the pretest, immediate posttest, and delayed posttest. Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test showed that they were comparable in terms of the difficulty level (z=-0.816,p=0.414). Each version comprising 10 sentences was adapted from an online test designed by ESL teachers (EnglishExercise.org).

Each test sentence was followed by three choices: (1) Grammatical, (2) Ungrammatical, and (3) Not Sure. In the case of (1), participants were simply to circle the answer; in (2), they were to underline and correct the perceived error; and in (3), they were to provide a brief explanation. A sample item is given in Figure 3.

Figure3 A sample GJT item

Each correct answer was awarded two points; each accurate indication of the error but with incorrect correction received one point; and each incorrect answer or incorrect indication of the error received zero point.

ControlledProductionTask

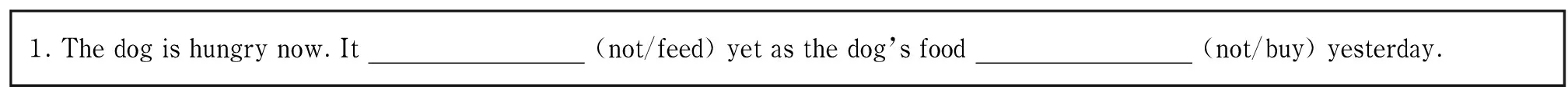

Similarly, three versions of a fill-in-the-blank task were created for the pretest, immediate posttest, and delayed posttest. Each version consisted of 10 different items adapted from the online test (EnglishExercise.org). The three versions had a comparable difficulty level (z=-1.300,p=0.194). One point was awarded for a correct answer and zero point for an incorrect answer. An example is provided in Figure 4.

Figure 4 A sample fill-in-the-blank item

FreeWrittenProductionTask

Three versions of a written narrative task (z=-0.552,p=0.581) were administered to elicit free written production of the target structure. In the pretest version, participants were asked to write a complaint letter to a wedding specialist, about the items that had not been prepared yet. Two sample sentences were provided to illustrate how to begin the letter (e.g.,Ivisitedyourofficetodaybutyouwereout.Ihaveseenthatmostoftheweddingarrangementshavenotyetbeenmade.Tobeginwith...). The immediate posttest version consisted of (a) reading an online article about the late Steve Job’s stolen iPad (about 250 words) and (b) retelling the story, via email, to a friend working at an Apple Store. The delayed posttest version involved condensing an onlineNewYorkTimesarticle “Crazy Pills” (about 900 words) into less than 500 words. The article reports on the use and regulations of the drugLariam.

The accuracy of production was assessed using a target-like-use formula (Pica, 1983). Since the study focused not only on the formal accuracy but also on the mapping of form, meaning, and use of the target structure, any grammatically felicitous constructions that were semantically anomalous (e.g.,anewmiraclehastobedeveloped) were coded as incorrect.

ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

Given the small sample size, a nonparametric Friedman Test was run with the treatment as the independent variable and the two posttest scores as the dependent variables. In addition, the participants’ scores on the pretest and two posttests were compared on another nonparametric test, the Wilcoxon Singed Rank Test, to ascertain the significance of the differences before and after the instructional treatment. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 22.0.0, with the level of significance set at 0.05.

GrammaticalityJudgmentTask(GJT)

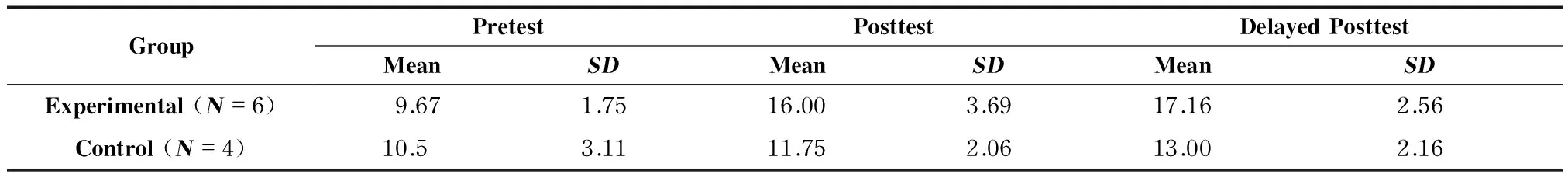

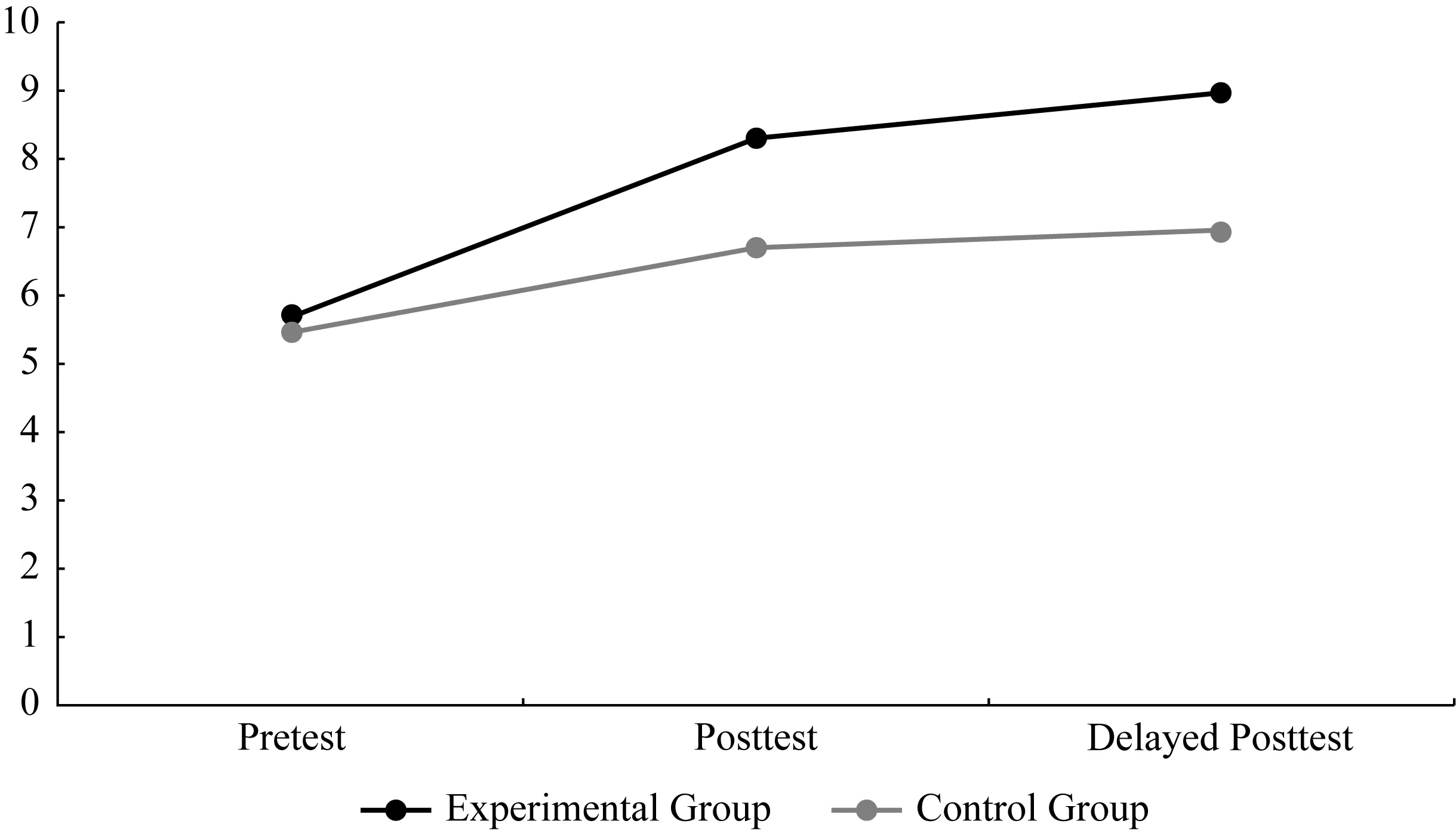

As shown in Table 2, the experimental group scored better than the control group in both posttests. Interestingly, compared with their pretest scores (M=9.67 for the experimental group andM=10.5 for the control group), participants generally performed better on both the immediate (M=16.00 and 11.75) and delayed posttests (M=17.16 and 13.00). When the changes from the pretest to the two posttests were compared visually (see Figure 5), however, the line of the experimental group exhibited a noticeably steeper slope than that of the control group.

Friedman Test results indicated a significant main effect for the explicit FonF (x2=9.364,df=2,p=0.009), whereas the increase of the scores in the control group was negligible (x2=2.000,df=2,p=0.368). Additionally, according to a Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test, the experimental group improved significantly in the immediate posttest (p=0.042), the effect sustained in the delayed posttest. Conversely, there was no measurable difference between the pretest, immediate posttest, and delayed posttest scores of the control group.

Table 2 Descriptive statistics for the GJT scores (max. score=20)

Figure 5 Pretest, Posttest, Delayed Posttest Scores of the GJT Tasks

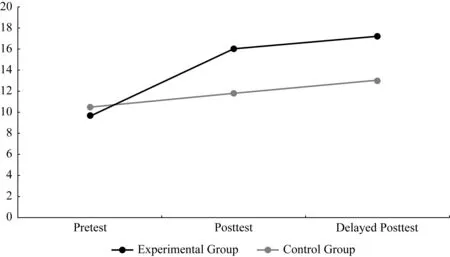

TheControlledWrittenProductionTask

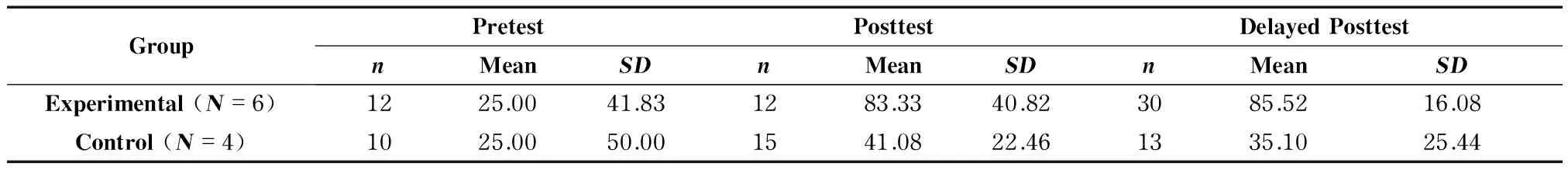

The overall results of the fill-in-the-blank tasks are summarized in Table 3. Similar to the GJT scores, the experimental group did noticeably better in both posttests, though the control group also showed slight improvement. The Friedman Test indicates that the instruction had a significant effect (x2=6.300,df=2,p=0.043) on the experimental group. Unlike the GJT results, however, the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test shows a significant change from the pretest to the delayed posttest (p=0.042); no such difference was observed between the pretest and immediate posttest (p=0.116). The control group showed no significant difference over time, from the pretest to the delayed posttest.

Table 3 Descriptive statistics for the fill-in-the-blank scores (max. score=10)

Figure 6 Pretest, Posttest, Delayed Posttest Scores of the Fill- in-the-Blank Tasks

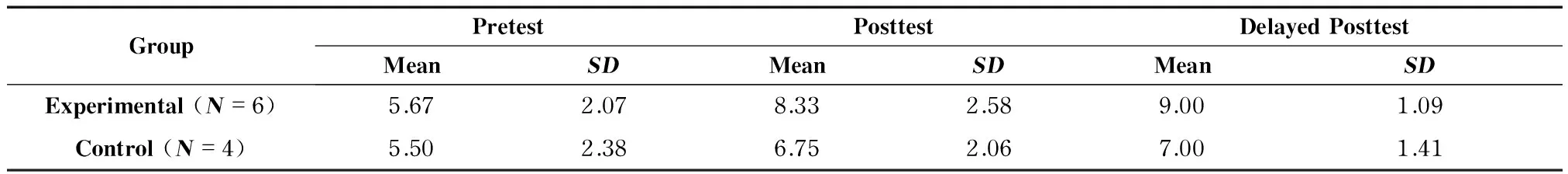

TheFreeWrittenProductionTask

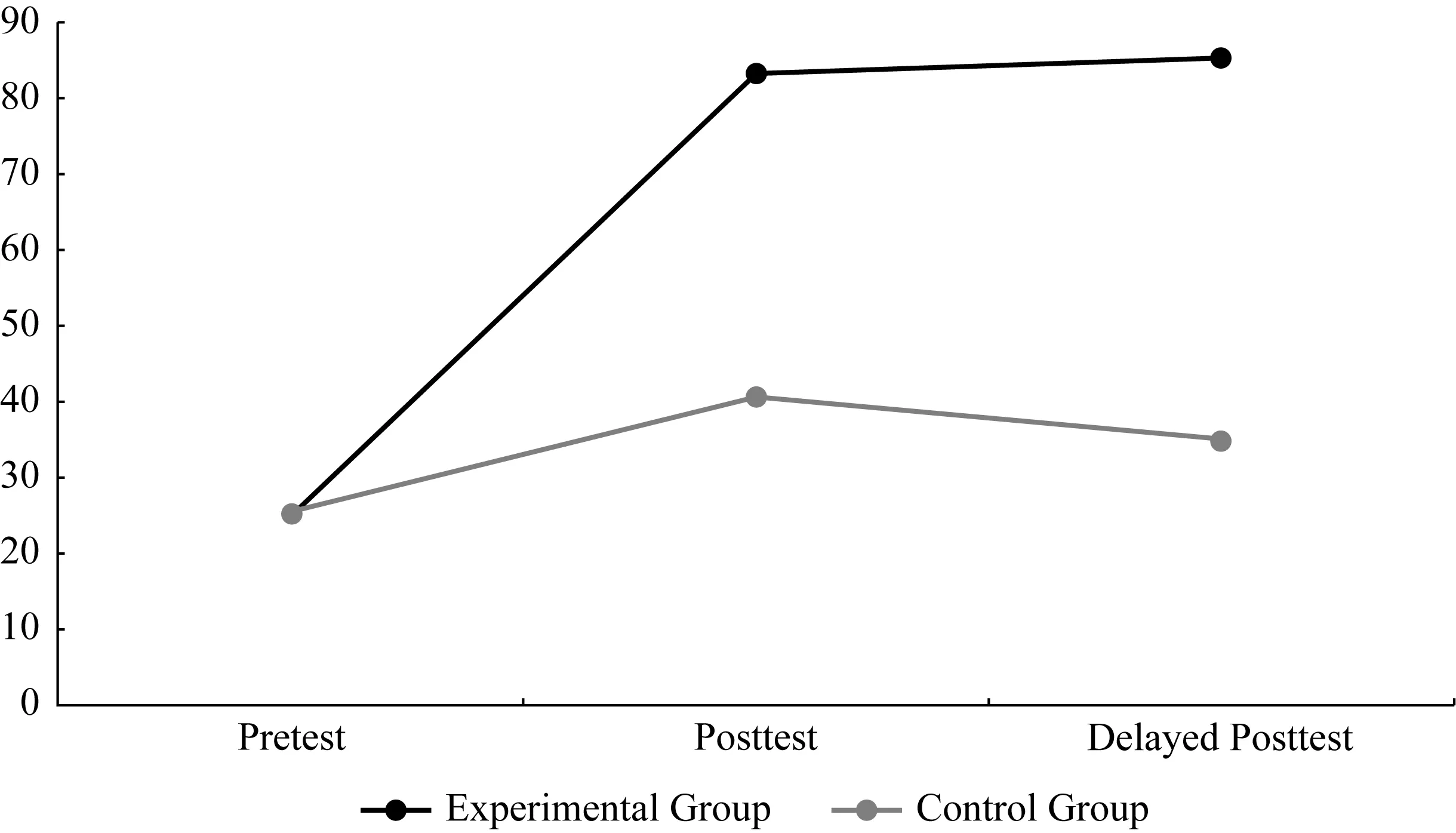

The free written production tasks produced the most intriguing findings. The overall results are presented in Table 4. As with the two previous tasks, the Friedman Test reveals that the participants’ free written production was affected significantly by the explicit FonF treatment (x2=7,df=2,p=0.030). While both the experimental and control groups performed similarly in the pretest and the immediate posttest, a significant difference showed up on the delayed posttest, with the experimental group outperforming the control group producing twice as many tokens of the target construction. Below are sample tokens of production from the free written production tasks.

1. Experimental group a. Tokens coded as “correct” (obligatory context)HisexperiencewascausedbythesideeffectofLariam.Drugscanbeimportedfromforeigncountriesbyillegalroutes.Therefore,productionofLariamhavetobestopped.Hewasfoundbyapolicemaninthetrainstationfourmilsawayhisapartment.Otherexamplescommittingsuicideormurderwerealsoreported.TheserioussideeffectsofLariamhadnotbeenopenedtothepublicforalongtime.However,thesideeffectisapttobeignoredbecauseitisinvisible.Ithasbeensaidthatasmallnumberofpeoplehavesymptomslikeamnesia.Ifthedrug’seffectswerevisible,itwouldhavebeeneliminatedfromthemarket.

b. Tokens coded as “incorrect” (non-obligatory context)Theauthor,calledDavidStuartMacLean,Hewasstayedinhospitalforthreedays.Sometravelershavebeenusedthisdrug.Andanewmiraclehavetobedeveloped.

c. Tokens copied from the texts and eliminated from codingOnly1in10000peoplewereestimatedtoexperiencetheworstsideeffects.SinceLariamwasapprovedin1989

2. Control group a. Tokens coded as “correct” (obligatory context)Afterthevictimsfoundthatitwascausedbythedrug,theysuedthecompany.Ittalkaboutcountlesshorrorcaseofpeoplewhohavebeenaffectedbydisturbancesandpractice.

b. Tokens coded as “incorrect” (non-obligatory context)Thebadsideeffectswillcausebythedrug.ItcausedofsideeffectofdrugLariam.Thearticletalkaboutlegaldrugsthatisprescript.

c. Tokens copied from the texts and eliminated from codingAnewmiracledrugisfoundandheraldedanddefendeduntilitdestroysenoughlives.

The treatment appears to have induced a developmental pattern that is unique to the experimental group. First, the experimental group exhibited substantial improvement from the pretest to the immediate posttest (M=25.00 versusM=83.33;p=0.059), and subsequently, significant improvement in the delayed posttest (p=0.042). The control group, on the other hand, though scoring higher on the immediate posttest, did not seem able to retain well the gain on the delayed posttest (M=25 versusM=41.08 andM=35.10). Second, there was considerable reduction of within-group variation for the experimental group from the immediate to the delayed posttest (SD=40.82 versusSD=16.08), while the control group exhibited similar amounts of variation (SD=22.46 versusSD=25.44). Of course, these results should not be overstated, given the small sample size.

Table 4 Descriptive Statistics for the Free Written Production Scores

Figure 7 Pretest, Posttest, and Delayed Posttest Scores of the Free Written Production Tasks

DISCUSSION

Based on the theoretical rationale of FonF and some empirical results from previous research (e.g., Doughty & Varela, 1998; Ellis & Sheen, 2006; Rosa & Leow, 2004), we hypothesized that the explicit FonF treatment in our study would benefit the experimental group who were engaged in C-R activities and who received metalinguistic explanation. Statistical analyses show that the treatment induced significantly better performance in the experimental group on all three outcome measures, and the gain was retained on the delayed posttest. Specifically, the two groups were alike at the onset of the study, but the experimental group outperformed the control group by more than oneSDunit on the GJT (d=4.25) and free written production (d=42.25) tasks and about oneSDunit (d=1.58) on the controlled production task in the immediate posttest. Greater differences were revealed in the delayed posttest: The experimental group significantly outperformed the control group by more than oneSDunit on the GJT (d=3.84), controlled production (d=2.00), and free written production (d=60.42) tasks. The benefit of the treatment was most pronounced on the free written production task, where more accurate production of the target structure and greater within-group homogeneity were observed for the experimental group, suggesting that the treatment had an overall impact on the individuals within the group. All of these constitute evidence that the explicit FonF treatment did improve the learners’ knowledge and use of the English passive construction.

Still, the results call for a more nuanced appreciation. As reported in the previous section, on two of the tasks, controlled production and free written production, the experimental and the control group performed better on the immediate posttest, albeit to varying extent, as seen in the differentpvalues (p=0.116 vs.p=0.059). Worthy of note here is that both groups, but especially the experimental group, performed differently on the two tasks. In general, when the sample size is small, individuals’ performance can easily tip the scale, and this is indeed what we see happen on the controlled production task (i.e., filling in the blanks). The relatively weaker performance of the experimental group on this task can be attributed to two individuals, E2 and E4, both of whom had had a relatively shorter length of residence in the U.S. than their peers. Seventy-five percent of their errors were related to the structurebedone, due to their lack of knowledge ofdone, the past participial form ofdo, which had a prominent presence in the immediate posttest (20% of the test items) but zero presence in the pretest and the delayed posttest. Interestingly yet not surprisingly, the two learners were not alike in their performance: E4 was consistent (e.g.,Dishesaredidbymysister,Laundryisdidbyme), while E2 exhibited random behavior (e.g.,Dishesaredobymysister,Laundryaredidbyme). Moreover, it appears that the treatment took longer to exert an influence on E4, who had had the shortest length of residence (i.e., one month) in the U.S. She showed no improvement in performance on any of the measures of the immediate posttest, but her delayed posttest scores from all three measures revealed a substantial gain. On the immediate GJT posttest, for example, she identified as ungrammatical such grammatically correct sentences involving the simple future tense asit[adressbeingfixednow]willbefinishedtomorrowandthey[documents]willbereviewedatthemeetingtomorrow, and corrected them intoitwillfinishedandtheywillreviewed. There might be a transfer effect here from her L1, Spanish, in which the passive voice is expressed by the copula verb ser (be-verb in English) conjugated in tense (i.e.,será, orserásforwillbein English) followed by the past participle of the main verb. On the delayed posttest, E4 correctly producedThegamewillbewonbywhoeverplaysthebest.

As reported in the previous section, the intensive FonF had the most noticeable effect on free production, and the gain was both substantial and lasting (M=83.33 for the immediate posttest andM=85.52 for the delayed posttest). In contrast, the control group, although showing some change in the immediate posttest, regressed in the delayed posttest by a quarter of an SD unit (M=35.10). This result lends support to a finding from previous research that exposure to input without further explicit instruction leads only to limited learning (e.g., Sharwood Smith, 1993; Winke, 2013). More studies are needed to further clarify this argument.

Apart from demonstrating a durable impact of intensive explicit FonF, the present study has shown that the explicit FonF in the form of C-R led not only to significantly better but also more homogeneous performance (SD=16.08). The passive constructions of the two groups differed not only quantitatively but also qualitatively. For example, whereas the experimental group produced mostly lexical errors (e.g.,Sometravelershavebeenusedthisdrug), the control group produced more syntactic errors (e.g.,Thebadsideeffectswillcausebythedrug).

The present study seemingly downplays an alleged weakness of intensive explicit instruction, namely that it can result in learners’ overuse of the target construction (Lightbown, 1983). While evidence was indeed found in the present study, its incidence was low—only three instances were observed in the experimental group’s written narratives (e.g.,sometravelershavebeenusedthisdrug,hewasstayedinhospitalforthreedays, andanewmiraclehastobedeveloped). Perhaps, the low number might have to do with the fact that the focus of the instruction concerned not merely the form, meaning, and use of the English passive but also other grammatical elements, such as tense and aspect. The broader focus may have helped to balance the experimental group’s attention to the target construction per se and to other more generally useful features such as tense and aspect. Of note, in addition to producing many more tokens of the passive construction (N=30) than did the control group (N=13) in the delayed posttest, the experimental group produced longer narratives (M=456 words), compared to the control group (M=321 words).

Interestingly, more instances of overproduction were observed in the performance of the control group. C3, for instance, produced several instances of overuse in her written narrative in the immediate posttest (e.g.,athiefwasenteredhishome;theclownwhowasreceivedit;hewasgainitbyKenneth). Since the control group received no focused instruction on the target structure, C3’s heightened awareness of the form may have stemmed from the textbook itself or even from peer communication outside the classroom about the intervention the experimental group was receiving.

Two other factors may have contributed to the positive results of the study. First, the measures employed—written GJT, gap filling, and written narration—may have allowed more efficient utilization of awareness, compared, for instance, to oral tasks. Second, due to their EFL background, the participants were, in general, amenable to explicit, metalinguistic instruction. Although their knowledge of the English passive appeared variable at the time of the pretest, the truth of the matter was that the participants had been taught the structure in junior and senior high schools, a standard grammar point in both EFL and ESL textbooks. In other words, the learners were ready for further instruction. This might also account for the gains observed in the control group.

CONCLUSION

The present study hypothesized that intensive explicit FonF would have a positive and durable impact on the learning of the English passive, a linguistically, psycholinguistically, and acquisitionally complex structure. The hypothesis was borne out, as in a number of previous studies (e.g., Gassetal., 2003; Housenetal., 2005; Hulstijn & Schmidt, 1994). The present study has shown, among other things, that a complex linguistic construction governed by verbalizable rules is amenable to explicit FonF, at least in the case of adult learners.

The positive results notwithstanding, the shortcomings of the study are obvious, which compromise the generalizability of its findings. The most obvious are the small sample size and the unmatched number of participants in the experimental and control groups. Somewhat less obvious, but no less important, are several weaknesses concerning the measures employed in the study. First, the assessment tasks, by virtue of their being untimed as opposed to timed (i.e., GJT) and written as opposed to oral (i.e. the two production tasks), favor the utilization of awareness, and, therefore, play to the advantage of the experimental group. Second, the GJT and fill-in-the-blank tasks included no distractors, which might have helped direct learner attention to the target construction. Last but not least, the three versions of the free written production task did not provide the same number of obligatory contexts, rendering impossible a straightforward comparison of the scores over time. Future studies must be mindful of these pitfalls in their design and execution.

Indeed, where assessment of the efficacy of explicit FonF is concerned, further research is needed on both conceptual and empirical levels. Theoretically, the concept of complexity requires a more nuanced understanding, and so does the concept of awareness. On the empirical level, future research would benefit from stronger methodological designs that, ideally, permit concurrent investigation of both explicit and implicit FonF, since the understanding of one may facilitate that of the other. Such studies should also target a wider range of structures, effectively control for extraneous factors (e.g., prior knowledge), and accurately measure both short-term and longer-term effects of instruction.

ISLA research has increasingly been hailed as an indispensible source of professional knowledge for second and foreign language teachers, but it is only through constant and conscientious efforts on the part of the researchers to make improvements to their studies that it is hopeful that the field will live up to the practitioners’ expectations.

Carroll, S. & Swain, M. (1993). Explicit and implicit negative feedback: An empirical study of the learning of linguistic generalizations.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 15(3), 357-389.

Carroll, S., Roberge, Y., & Swain, M. (1992). The role of feedback in adult second language acquisition: Error correction and morphological generalizations.AppliedPsycholinguistics, 13(2), 173-198.

De Graaff, R. (1997). The eXperanto experiment: Effects of explicit instruction on second language acquisition.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 19(2), 249-297.

DeKeyser, R. (1995). Learning second language grammar rules: An experiment with a miniature linguistic system.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 17(3), 379-410.

Doughty, C. (1991). Second language instruction does make a difference: Evidence from an empirical study of ESL relativization.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 13(4), 431-469.Doughty, C. (2003). Instructed SLA: Constraints, compensation, and enhancement. In C. Doughty & M. H. Long (Eds.),Thehandbookofsecondlanguageacquisition(pp. 256-310). Malden: Blackwell.

Doughty, C. & Varela, E. (1998). Communicative focus on form. In C. Doughty & J. Williams (Eds.),Focusonforminclassroomsecondlanguageacquisition(pp. 114-138). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Doughty, C. & Williams, J. (1998).Focusonforminclassroomsecondlanguageacquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Ellis, N. (2008). Implicit and explicit knowledge about language. In J. Cenoz & N. Hornberger (Eds.),Encyclopediaoflanguageandeducation(pp. 119-131). New York: Springer.

Ellis, R. (2002a). Does form-focused instruction affect the acquisition of implicit knowledge?: A review of the research.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 24(2), 223-236.Ellis, R. (2002b). Grammar teaching: Practice or consciousness-raising? In J. C. Richards & W. A. Renandya (Eds.),Methodologyinlanguageteaching:Ananthologyofcurrentpractice(pp. 167-174). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ellis, R., Loewen, S., & Erlam, R. (2006). Implicit and explicit corrective feedback and the acquisition of L2 grammar.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 28(2), 339-368.Ellis, R. & Sheen, Y. (2006). Re-examining the role of recasts in L2 acquisition.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 28(4), 575-600.Fotos, S. & Ellis, R. (1991). Communicating about grammar: A task-based approach.TESOLQuarterly, 25(4), 605-628.Gass, S. & Selinker, L. (2008).Secondlanguageacquisition:Anintroductorycourse. New York: Routledge.

Gass, S., Svetics, I., & Lemelin, S. (2003). Differential effects of attention.LanguageLearning, 53(3), 497-545.

Han, Z -H. (2000). Persistence of the implicit influence of NL: The case of the pseudo-passive.AppliedLinguistics, 21(1), 78-105.

Han, Z -H. (2002). A study of the impact of recasts on tense consistency in L2 output.TESOLQuarterly, 36(4), 543-572.

Han, Z-H. (2004).Fossilizationinadultsecondlanguageacquisition. New York: Multilingual Matters.

Han, Z-H. & Lew, W. (2012). Acquisitional complexity. In B. Kortmann & B. Szmrecsanyi (Eds.),Languagecomplexity(pp. 192-217). Boston, MA: Walter de Gruyter.

Hulstijn, J. & De Graaff, R. (1994). Under what condition does explicit knowledge of a second language facilitate the acquisition of implicit knowledge?AILAReview, 11, 97-112.

Hulstijn, J. & Schmidt, R. (1994). How implicit can adult second language learning be?AILAReview, 11, 83-96.

Housen, A., Pierrard, M., & Van Daele, S. (2005). Rule complexity and the efficacy of explicit grammar instruction. In A. Housen & M. Pierrard (Eds.),Investigationsininstructedsecondlanguageacquisition(pp. 235-269). Amsterdam: Mouton de Gruyter.

Krashen, S. (1982).Principlesandpracticeinsecondlanguageacquisition. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Le Coq, P, J. (1944). A neglected point of grammar in the passive voice.TheModernLanguageJournal, 28(2), 117-122.

Leeman, J. (2003). Recasts and second language development: Beyond negative evidence.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 25(1), 37-63.

Lightbown, P. (1983). Exploring relationships between developmental and instructional sequences in L2 acquisition. In H. Selger & M. Long (Eds.),Classroomorientedresearchinsecondlanguageacquisition (pp. 217-243). Rowley: Newbury House.

Lightbown, P. & Spada, N. (1990). Focus on form and corrective feedback in communicative language teaching: Effects on second language learning.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 12(4), 429-448.

Long, M. (1991). Focus on form: A design feature in language teaching methodology. In K. de Bot, R. Ginsberg & C. Kramsch (Eds.),Foreignlanguageresearchincross-culturalperspective(pp. 39-52). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Long, M. (2014).Secondlanguageacquisitionandtask-basedlanguageteaching. New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

Mackey, A. & Goo, J. (2007). Interaction research in SLA: A meta-analysis and research synthesis. In A. Mackey (Ed.),Conversationalinteractioninsecondlanguageacquisition:Aseriesofempiricalstudies(pp. 407-452). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Murunoi, H. (2000). Focus on form through interaction enhancement.LanguageLearning, 50(4), 617-673.Norris, J. & Ortega, L. (2000). Effectiveness of L2 instruction: A research synthesis and quantitative meta-analysis.LanguageLearning, 50(3), 417-528.

Norris, J. & Ortega, L. (2001). Does type of instruction make a difference? Substantive findings from a meta-analytic review. In R. Ellis (Ed.),Form-focusedinstructionandsecondlanguagelearning(pp. 157-213). New York: Blackwell.

Philp, J. (2003). Constraints on “noticing the gap”.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 25(1), 99-126.

Pica, T. (1983). Methods of morpheme quantification: Their effect on the interpretation of second language data.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 6(1), 69-78.Pienemann, M. (1989). Is language teachable?: Psycholinguistic experiments and hypotheses.AppliedLinguistics, 10(1), 52-79.

Reber, A. S. (1989). Implicit learning and tacit knowledge.JournalofExperimentalPsychology:General, 118(3), 219-235.

Reichenbach, H. (1947).Elementsofsymboliclogic. New York: Macmillan.

Robinson, P. (1996). Learning simple and complex second language rules under implicit, incidental, rule-search, and instructed conditions.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 18(1), 27-68.

Rosa, E. & Leow, R. (2004). Awareness, different learning conditions, and second language development.AppliedPsycholinguistics, 25(2), 269-292.Rutherford, W., & Sharwood Smith, M. (1985). Consciousness-raising and universal grammar.AppliedLinguistics, 6(3), 274-281.

Schmidt, R. (1990). The role of consciousness in second language learning.AppliedLinguistics, 11(2), 129-158.

Sharwood Smith, M. (1993). Input enhancement in instructed SLA: Theoretical bases.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 15(2), 165-179.

Sorace, A. (2005). Syntactic optionality at interfaces. In L. Cornips & K. Corrigan (Eds.),Syntaxandvariation:Reconcilingthebiologicalandthesocial(pp. 46-111). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Spada, N. & Lightbown, P. (1993). Instruction and the development of questions in the L2 classroom.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 15(2), 205-221.

Spada, N., Lightbown, P., & White, L. (2005). The importance of form/meaning mappings in explicit form-focused instruction. In A. Housen & M. Pierrard (Eds.),Investigationsininstructedsecondlanguageacquisition(pp. 199-234). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Spada, N. & Tomita, Y. (2010). Interactions between type of instruction and type of language feature: A meta-analysis.LanguageLearning, 60(2), 263-308.

Spinner, P. (2011). Second language assessment and morphosyntactic development.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 33(4), 529-561.

Varnosfadrani, D. A. & Basturkmen, H. (2009). The effectiveness of implicit and explicit error correction on learners’ performance.System, 37(1), 82-98.

White, L. (1991). Adverb placement in second language acquisition: Some effects of positive and negative evidence in the classroom.SecondLanguageResearch, 7(2), 133-161.

Williams, J. & Evans, J. (1998). What kind of focus and on which forms?. In C. Doughty & J. Williams (Eds.),Focusonforminclassroomsecondlanguageacquisition(pp. 139-155). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Winke, P. (2013). The effects of input enhancement on grammar learning and comprehension.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 35(2), 323-352.

10.3969/j.issn.1674-8921.2014.12.003

Correspondence should be addressed to Ji-Yung Jung, Teachers College, Columbia University, USA. Email: muellerj@umd.eduin

- 當代外語研究的其它文章

- How to Make L2 Easier to Process? The Role of L2 Proficiency andSemantic Category in Translation Priming

- Call For Papers

- Language Learning Strategies in China: A Call for Teacher-friendlyResearch

- A Meta-analysis of Cross-linguistic Syntactic Priming Effects

- Development of Implicit and Explicit Knowledge of GrammaticalStructures in Chinese EFL Learners

- Extending the Distributional Bias Hypothesis to the Acquisition ofHonorific Morphology in L2 Korean