Language Learning Strategies in China: A Call for Teacher-friendlyResearch

YONGQI GU

Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

LanguageLearningStrategiesinChina:ACallforTeacher-friendlyResearch

YONGQI GU

Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

The astronomical number of people learning English in China and a small proportion of success stories mean a practical demand of research that focuses on learning how to learn. Research interest in language learning strategies started in China in the early 1990s and gradually gained momentum and peaked around twenty years later. The staggering amount of publications on the topic, however, has not produced the expected impact on learning and teaching, mainly because of the fact that the research has not been well applied. Meanwhile, a few findings can be said to have been over applied. These mainly include an over-emphasis on memory strategies and on the intentional learning of explicit knowledge. Luckily, some research findings have been well applied. Apart from providing many insights into strategic learning, research on language learning strategies has seen its salient impact on the national curriculum for basic education and on the textbooks. It is contended that researchers should re-orientate our research agenda from knowledge accumulation to knowledge application, and from facilitating learning to empowering learners.

language learning strategies, applicable findings

INTRODUCTION

At least 240-million Chinese students at various levels are learning English as a foreign language (EFL) in China (MOE China, 2010). Only a tiny proportion of these learners can achieve a level of proficiency good enough for communication in English. The Herculean task of learning means that finding effective and efficient ways of learning will be among the most popular research interests. Indeed, learning strategies (LS) for EFL learning in China have received a lot of research attention.

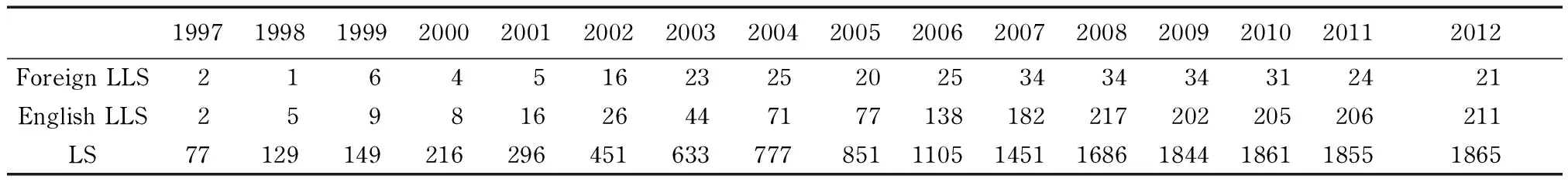

This article is not meant to be a comprehensive and systematic review of language learning strategy (LLS) research published in China. In fact, I will be deliberately brief about achievements over the last thirty years. Focus will be placed upon the application of research findings. That said, many insights do come from my analysis of journal publications on the topic included in the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), a large database that has digitised almost all formal publications in China since its establishment in 1999. A search of “English language learning strategies”, “foreign language learning strategies”, and “l(fā)earning strategies” in CNKI shows that the number of publications on the topic rapidly increased over the years and peaked around 2006-2009 (See Table 1).

Table 1 Number of publications by year (1997-2012)

My observations in this article are mainly based on the 67 most cited articles with a minimum of 100 citations each centrally related to EFL learning strategies and autonomous learning, ranging from 1737 citations (Wen, 2001) to 107 citations (Yao, 2000).

Drawing on forty years of research on the topic throughout the world, as well as the list of most cited articles and other publications in China—e.g., the national curriculum standards and a widely used textbook series (Wang & Editorial team, 2009a), I will first present a general summary of the research, and then provide my own judgement as to the areas of research that have been well applied, not well applied, or over applied.

STRATEGIC LANGUAGE LEARNING: WHAT ITIS AND WHAT IT IS FOR

Strategic learning refers to a learner’s active, intentional engagement in the learning process by selectively attending to a learning problem, mobilising available resources, deciding on the best available plan for action, carrying out the plan, monitoring the performance, and evaluating the results for future action. Strategic learning is triggered and defined by task demands and is tied to a purpose. The purpose of strategic learning is to solve a learning problem, perform a novel task, accelerate the learning rate, or to achieve overall learning success.

The above definition focuses on the individual learner’s active engagement with the learning task. This focus on the learner and his/her own desires, aspirations and efforts for success in language learning comes from the cognitive tradition of learning theories. As such, it has been seen as promoting a “marginalised, psychologised, individualised and decontextualized” version of learner autonomy (Pennycook, 1997). For many scholars (e.g., Canagarajah, 2006), learner strategy is “defined at the most micro level of consideration in somewhat individualistic and psychological terms”, and may therefore “l(fā)ack direction without a larger set of pedagogical principles” (p. 20). Indeed, researchers now believe that LLS do not have to be confined to the “individualistic” and “psychologised” focus on language learning outcomes. Getting students engaged in their own process of learning and reflecting on how they can learn better is to ensure that learners obtain a sense of control, and eventually establish their own voice in the target language, and be able to author their own lives (Pennycook, 1997). Similarly, Brown (1991) is upbeat about a “transformative” role of LLS as early as 1991, and views learner strategy training as “the strategic investment of learners in their own linguistic destinies” (p. 256).

Another way of broadening the strategic learning concept is the widely accepted integration of learning strategy and learner autonomy (Oxford, 2011; Wen & Wang, 2004). In other words, successful use of learning strategies should lead to not only higher proficiency in language, but also more learner autonomy. This also entails a more balanced perspective of strategic learning, between the individual and the social side of learning, in that the strategic and autonomous learner not only actively self-regulates his/her own learning process, but is also keenly aware of the situatedness and the social nature of the learning task. Littlewood (1996) postulates three components of autonomous learning: the autonomous learner, the autonomous communicator, and the autonomous person. In other words, teachers can help their students become self-regulated learners, strategic communicators and users of the language, and proactive, self-reflective members of society who are keenly aware of the balance between the self and others around him/her. By the same token, LLS research should eventually aim to empower learners as learners, communicators, and socially responsible problem solvers as well. All these may sound a tall order, but they do coincide with traditional expectations of teachers in the Chinese context, in that teachers are expected to play two roles, in both instructing (jiao shu) and educating (yu ren) (Jin & Cortazzi, 1998). In this sense, LLS researchers should and can make our research useful.

WHAT HAVE WE LEARNED ABOUT STRATEGICLANGUAGE LEARNING?

Academic interest in the strategic learning of a second/foreign language started with Rubin (1975) and Stern’s (1975) lists of “good” language learning behaviours (e.g., guessing, risk-taking, and actively using what has been learned) that were thought to be precursory qualities for the successful learning of a second language. The lists were substantially expanded during the 1980s and 1990s when researchers went to the classrooms and learners to collect the naturally occurring strategies for language learning. LLS research was introduced to China at the beginning of the 1990s, especially with the publication of Wen’s landmark study inForeignLanguageTeachingandResearch(Wen, 1995). Today, LLS research in China has gone a long way in understanding the nature of strategic language learning, from initial exploratory examinations of “l(fā)anguage learning strategies” to a much more detailed look at strategies for different aspects of language learning, and reflective summaries of learner strategy research.

Many of these studies employed exploratory approaches and investigated the strategy use of Chinese students in performing various aspects of English language learning. For example, Zhang (2005) used a survey and correlated five types of metacognitive strategies with general proficiency grades. Yang (2003) used a writing strategies questionnaire and a think-aloud approach to discover that successful and unsuccessful writers used different writing strategies at different stages of writing. He and Liu (2004) combined a survey with a corpus-based approach and discovered that communication strategies were employed more by low oral proficiency students than by their high oral proficiency counterparts, and that the low oral proficiency group mainly used L1-based strategies, time-gaining strategies and reduction strategies while the high oral proficiency group mainly used L2-based strategies.

While a number of studies (e.g., Wang & Yin, 2003; Wen & Wang, 2004b) attempted to put learner strategies in an overall framework of interrelated factors, Wen and Wang’s (2004a) insightful reflections and critiques added considerable depth in current thinking on learner strategies. They first reviewed findings on three common research threads: strategic differences between top and bottom scoring students, predictive power of strategies, and effects of strategy training. Next they pointed out some of the fallacies in a few underlying assumptions. For example, current research has focused much attention on the strategies that the top students use exclusively at the expense of those strategies that are used by both top and bottom students. When both groups use the same strategies or a substantial proportion of students in each group use the same strategies, the effects of these strategies will be cancelled out and their predictive power will not be shown in a statistical analysis. This, however, should not be taken as meaning that these shared strategies between top scorers and low scorers are not useful in learning. Wen and Wang also rightly maintained that the ultimate purpose of strategy training is learner autonomy which is not something that is achievable within a short period of time. In sum, they argued that the relationship between learner strategies and learning results is much more complex than a linear model can offer. For many strategies, e.g. guessing, excessive use beyond the appropriate level will not result in positive learning results. Many strategies arise out of learning difficulties. In some circumstances, good learners will have less problems and therefore many problem solving strategies will not need to be activated.

One study (Lu, 2002) is worth mentioning in that it tried to explore the relationship between metacognitive and cognitive strategies in meticulous detail. It focused on the effects of metacognitive judgment of learning aim, task difficulty, time pressure, and perceived interest on the cognitive strategy of time allocation. Three experiments were used to manipulate the conditions of metacognitive judgment. Results showed that in free reading, the subjects allocated more time to materials that were judged to be easy; while in a reading for test condition, the subjects allocated more time to difficult materials. When under high time pressure, the subjects allocated more time to easy materials; while under less time pressure, the subjects allocated more time to difficult materials. Under all conditions, materials that were judged to be more interesting were given more time. While I believe that learner strategies research should continue to explore patterns of strategy choice and use and their relationship to learning results, studies like this that explore particular aspects of strategy choice and use should receive more attention.

To sum up, LLS research in China has answered some major exploratory questions such as “What strategies do Chinese EFL learners use?” “How are these strategies related to learning results?” and “Do successful learners and unsuccessful learners use different strategies?” Like LLS research elsewhere, a large repertoire of strategies for the learning of the four skills and vocabulary has been identified, and is found to be correlated with learning outcomes. The relationship between strategy choice, use, and effectiveness has been found to be complicated, and mediated by various learner-, task-, and context-related factors. While this is quite an achievement, research on LLS has generally failed to produce the practical impact on teaching and learning many had hoped for at the beginning of our field (e.g., Rubin, 1975).

HAS RESEARCH ON LLS MADE A DIFFERENECTO EFL CLASSROOMS?

The majority of studies on LLS in China have focused on exploring and establishing a relationship between LS and some measures of learning outcomes. These findings have exerted limited influence on the ways students learn and the ways teachers teach. In fact, most research findings hardly reach the classroom at all. Even if they do, teachers and learners have little idea as to how these findings can be applied to teaching and learning tasks. With the exception of a few, e.g. Gu, Hu, Zhang, and Bai (2011), which provides detailed rationale, materials, and procedures for strategy-based instruction in the classroom, most publications are directed at the academic community, and their research findings are normally not packaged in ways that are accessible to teachers and learners in the classroom.

One type of research, strategy intervention, has reached the classroom, albeit mostly for research purposes. For example, Yang (2003) trained a group of freshman students on their use of metacognitive strategies for listening and reported some positive results on both listening improvement and strategy use. Wang (2002) trained a group of second year English majors on three communication strategies (topic avoidance or replacement, circumlocution, and stalling devices) over a 20-week period and found that the training was useful in increasing the frequency of strategy use. In particular, increasing the use of fillers improved the fluency of these students. Meng’s (2004) intervention involved two classes of university non-English majors (n=84). The experimental class was taught four reading strategies (skimming, scanning, making global inferences, and making lexical inferences) for 12 weeks. At the end of the training, the experimental class outperformed the control class on a reading comprehension test and on a test of reading speed. Interestingly, Meng also compared the training effect on the four types of comprehension questions involved in the reading test. Strategy training was found useful in questions that focused on the main idea, global inferencing and new word guessing, but not on finding detailed information in the text. It should be noted that a number of these studies do not include details as to what exactly was trained, why, how the training took place, and how effectiveness was exactly measured. As such, teachers will find it hard to make use of the research findings.

Indeed, while these studies reveal some useful findings about the importance of strategy instruction, it has been hard to find articles that describe how classroom teachers have incorporated some of these findings successfully. One apparent reason is that these articles normally do not reach teachers. And even if they do, teachers do not get enough information as to what exactly each strategy is, and how exactly it is used to obtain the beneficial effect described in the published reports. The majority of Chinese journals publish very short articles that cannot accommodate a detailed methodology section. Sometimes even the findings section can also be very short and sketchy. For most of the intervention studies, readers are normally not given the instruction materials and the step-by-step procedures for strategy intervention, making it very hard for teachers to apply the research results in their classrooms. For example, in a report on the development of LLS among early primary school pupils published by a flagship journal for school teachers (Institute of Foreign Language Teaching and Teacher Education, Beijing Normal University, Beijing Institute of Curriculum Studies, & The Primary School Integrated Curriculum Reform Experiment Project Team, 2008), strategy training details were totally removed from the report. Instead, nine tables of statistics were presented. Research reports like this will not be helpful in guiding teachers on incorporating strategy training inside their classrooms.

The problem is especially serious at the primary or secondary school levels. There is enough evidence suggesting that when classroom teachers talk about LLS, they mean their own perceived methods of language learning, perceptions from their own experiences as learners and from their informal observations as teachers (experience-based) rather than from research findings (research-informed). In a survey of “strategy guidance” by junior secondary school teachers of English, Wang (2011) asked 62 teachers to report on their LS guidance in teaching. Although these teachers reported a moderate level of strategy guidance on the questionnaire (with frequency averages between 3.38 and 4.04 on a 5-point Likert scale), follow-up interviews indicated that the teachers basically understood strategy guidance as experience-based general ways of helping students learn, e.g. memorising words, categorising rules, planning revision, and encouraging students to participate in class. The only article I have found that gave some detailed guidance on how teachers should incorporate strategy instruction into their regular teaching practices, talked about strategies of analysis, revision, induction, planning, and making use of resources (Xiang, 2010). There is no indication that these suggestions were based on insights from previous research on LLS. To my knowledge, practical textbooks such as Ellis and Sinclair (1989) and Chamot Barnhardt, El-Dinary, and Robbins (1999) providing research-based advice on LLS are not available in China. Chinese researchers have in general not bothered to compile such practical texts for classroom teachers either.

For tertiary level teachers of English who should be more informed than school teachers in terms of access to LLS research findings, many articles introduce the idea of LLS instruction (e.g., Liu & Fu, 2003; Hou & Dai, 2011). A number of studies can be found reporting the effect of strategy instruction (e.g., Cheng, 2006). There is, however, little evidence suggesting that LLS research has been widely drawn upon in the teaching and learning of English at the tertiary level. In a comparison between teachers’ (N=35) teaching and students’ (N=174) learning of listening strategies at a top university in Shanghai, Ji & He (2004) found that the teachers reported a moderate level of frequency in teaching metacognitive strategies (M=3.18), cognitive strategies (M=3.17), and social/affective strategies (M=3.14) on a 5-point Likert scale. Their students’ reported frequency of strategy use was found to be lower (M=2.93, 3.04, and 2.69 respectively). The report did not include details about the teachers’ and the students’ understanding of LS and exactly how the strategy instruction was done. Since no qualitative descriptions of how LS were taught or used could be found, the self-report data could hardly form convincing evidence for anything.

Out of the 67 most cited articles in the CNKI related to LLS, 14 focused on an aspect of learner autonomy. Some studies (e.g., Xuetal. 2004) explored the status quo of learner autonomy among Chinese students, but the majority presumed the usefulness in fostering learner autonomy. On the one hand, the popularity of the topic is encouraging, especially in fostering independent learning habits. On the other hand, most of these publications stopped short of seeing the relevance of learner autonomy and LLS as tools for the establishment of a voice in a foreign language at individual and social levels. In other words, almost all LS and learner autonomy studies have taken a weak (Smith, 2003) or narrow (Kumaravadivelu, 2003) approach to the concepts, seeing them as “l(fā)earning to learn”, and not “l(fā)earning to communicate”, not to mention “l(fā)earning to be” (Littlewood, 1996). Rarely can we see research aimed at the nurturing of proactive, self-reflective, and self-regulated, responsible members of society. Not much can be found about teachers making use of research findings on fostering learner autonomy either.

One reason why LLS research in China has in general not reached its target consumers, as it were, must be due to the fact that people doing the research are mostly academics in tertiary institutions, and their audience are in actual fact their peers in academia. Only one (Ge, 2006) of the most cited publications on LLS focused on secondary school learners; another (Si, Zhao, & He, 2005) focused on students at the vocational level; and the remaining either focused on LLS at the tertiary level, or talked about LLS in general. China’s examination culture must have also played a part in preventing LLS research from reaching the classroom. Even if classroom teachers are informed about research findings, the pressure from high-stakes examinations would mean that the majority of the strategies may well become irrelevant in real learning situations where students are mostly interested in getting high scores in exams rather than learning and using the language, not to mention becoming independent learners, or thinking and responsible members of society. If the above reasons are generally out of the researcher’s control, the following reason is very much at the heart of the researcher’s own choice. For many researchers, the ultimate goal of research is publication and not application. In this sense, improving the usefulness of LLS research must start from researchers, in becoming more aware of our social and educational responsibilities, and in a re-orientation of research criteria from publishability to usefulness.

PRAISE-WORTHY APPLICATION EFFORTS

Despite the general pattern I describe above, certain aspects of LLS research have been well applied. Researchers now know much more about how Chinese learners learn English than we did 20 years ago. In fact, this knowledge has become so deeply rooted that LLS has become one of the five curriculum targets in China since 2001, along with language skills, knowledge about language, affect and attitudes, and cultural awareness (MOE China, 2001, 2003, 2011). LLS is also incorporated into textbooks designed after 2001. In addition, a few researchers have tried to integrate research findings on LLS into an online learner support system.

Curriculumintegration

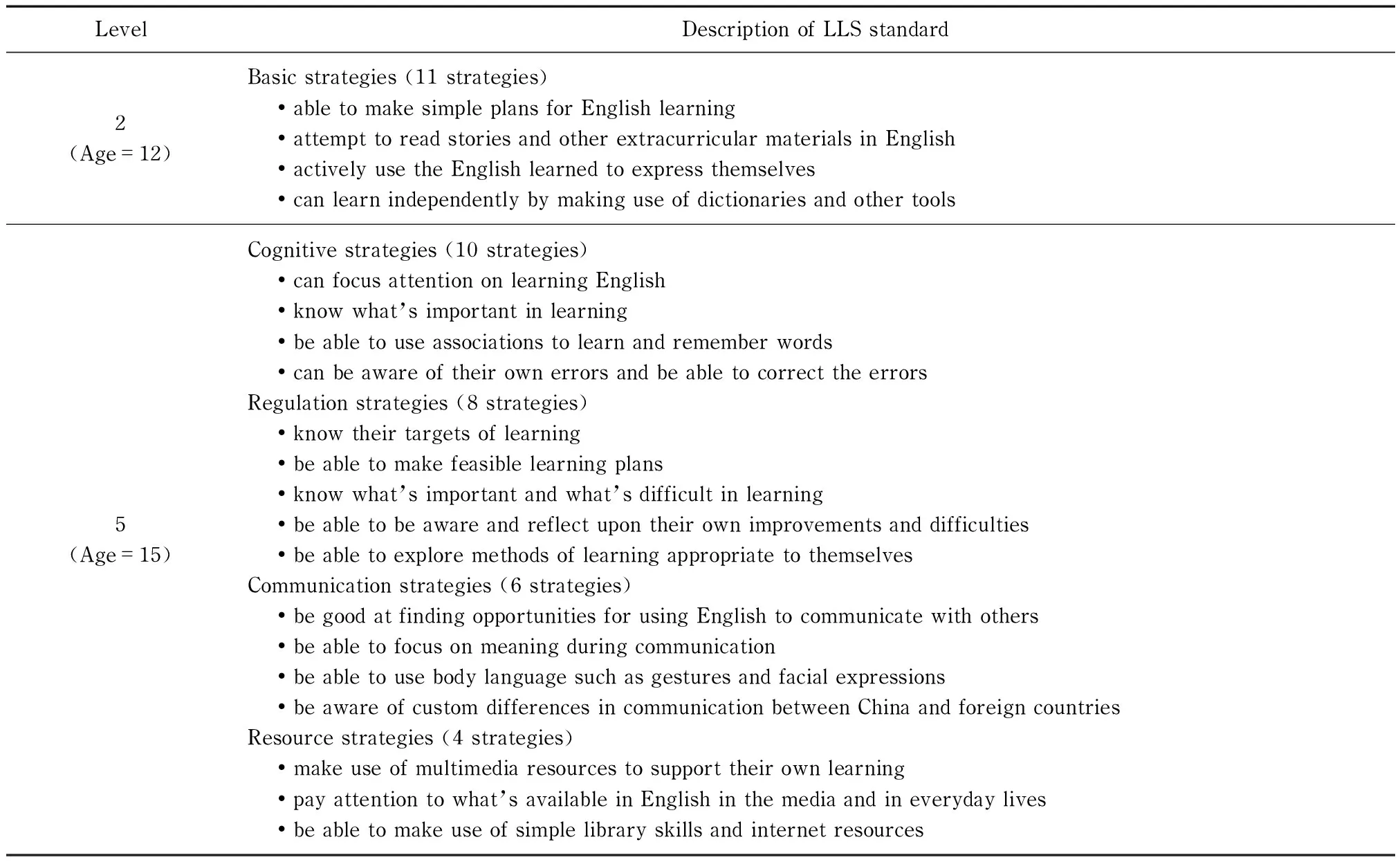

One area where LLS research has been well applied is curriculum integration. In fact, I am not aware of any other national curriculum that explicitly spells out LS as a major curricular target. Starting from 2001, China’s national curriculum standards have included not only a mention of LLS, but also explicit strategy standards for levels 2, 5, and 8, which correspond to the end targets at Grade 6 for primary school, Grade 9 for junior secondary school, and Grade 12 for senior secondary school respectively (MOE China, 2001, 2003, 2011).

In the latest curriculum standards for compulsory education (which ends at Grade 9 or the end of junior secondary school) (MOE China, 2011), five types of LLS are listed as the curriculum targets for strategies. At the end of primary school (level 2), students should be able to obtain eleven “basic strategies”, including, for example, “being able to make simple plans for English learning”. By the end of junior secondary school (level 5), students should be able to make use of ten “cognitive strategies”, eight “regulation strategies”, six “communication strategies”, and four “resource strategies”. Table 2 below includes examples taken and translated from the 2011 curriculum standards.

Table 2 Learning strategy standards by level (adapted from MOE China, 2011: 22-23)

Of course, explicitly including LLS standards in the national curriculum does not necessarily lead to classroom implementation. In a classroom observation study not designed to study LLS (Gu, 2014), a senior secondary school teacher simply ignored the references to LLS in the curriculum and the textbook (see next section). Teachers shouldn’t be blamed for the lack of implementation, because they are not given information as to what it means to have reached the curricular target for each strategy; nor do they know how exactly strategy performances should be promoted and evaluated. There is also a lack of transparency as to why these strategies and not others were chosen in the first place. Despite all these problems, having some concrete targets in the curriculum standards is arguably one of the best ways in making teachers and learners aware of the importance of strategic learning.

TextbookintegrationofLLS

Some new textbooks published with the express purpose of implementing the curriculum standards (e.g., Wang & Editorial team, 2009a) have included LLS. InSeniorHighEnglish, for example, there is aLearningtolearnsection at the beginning of each compulsory module of the Learner’s Book, which aims to foster learner independence by informing learners what the module covers, how to make use of dictionaries, how to organise vocabulary books and make grammar notes (Wang & Editorial team, 2009b, p. 9). In each theme-based unit of teaching, there are strategy boxes that contain a few strategy tips for a particular task (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1 Strategy boxes in Unit 11 of Senior High English

This is definitely an encouraging sign. However, to what extent are these strategies related to the strategies listed in the curriculum standards? To what extent are they applications of research findings? A quick look at the list does not give me a very positive answer. For example, the listening strategies look more like test-taking strategies than strategies for an authentic listening task. Further questions that arise immediately would have to include “Are teachers teaching these strategies?” and “Are students able to make use of these strategies?” Again, answers are not that encouraging. The strategies for reading suggest that learners guess what an expression means, and if they are not able to guess, look it up in a dictionary, an atlas or an encyclopaedia. The point is: learners are not taught how to guess, or how to look up an expression in a dictionary. In the teacher’s book (Wang & Editorial team, 2009b), the guide reads:

?Read the strategies with the class.

?Have students look at the newspapers you have brought in and find cultural references that would not be familiar to a British or American reader.

?In pairs, students underline names in the texts and classify them into the given categories (p. 44).

Previous research informs us that teachers need to show how a task is done before students can be expected to perform the task strategically (Crabbe, 1993). This means that simply reading the strategies to the class will not be useful. In fact, video recordings of a senior teacher teaching this unit in a key school in Beijing (Gu, 2014) showed that the strategies part of the teaching and learning aims were completely ignored in the classroom. This shows the importance of teacher education in the integration of LLS. Despite the good practice of listing LLS in the curriculum and including LLS in the textbook, more concrete research findings such as what strategies Chinese EFL learners need to learn at which level, and how best they should be learned and taught should be taken into consideration before classroom integration of LLS can become a fruitful reality.

Learningstrategiesinlearnerguidance

Another area where research on LLS has been applied is exemplified by one group of scholars’ work on integrating LLS into a “Personalized Online System for Diagnosis and Advice in English Learning Strategies” (Ma & Meng, 2008; Ma Xiaomei Research Team, 2008). This is a web-based system where students can log on and get diagnostic information and then advice for learning, plus customised exercises in language skills, personality, learning style, and LS. Conceptualisation of the whole system was based on an analysis of theoretical and empirical research on learner variables, learning styles, language learning theories and LS. The system comprises four modules: (1) a self-diagnosis module which elicits a learner’s personality type, learning style, motivation and LS; (2) a dynamic diagnosis module that tries to establish a student’s current ways of learning, e.g. reading behaviours; (3) an ”autonomous learning and strategic guidance” module that provides customised guidance based on the information obtained from 1 and 2 above; and (4) an independent module, which provides narratives from successful learners about how they have achieved success. This is a very innovative system that makes integrated use of not just research results on LLS but also how LS work in relation to task demands and personal preferences. Despite a lack of research findings in terms of its effectiveness, the system has reportedly received very encouraging feedback from users.

A FEW MORE WORRIES

The whole idea of strategic learning assumes intentional and deliberate learning of certain targeted aspects of language competence. While an emphasis on strategic learning does not rule out the intentional use of appropriate strategies for the incidental learning of implicit skills, there is a potential danger of overlooking the incidental aspects of learning which are necessary for the building of skills, and for the contextualised, intuitive and implicit competence of language in use. This is especially true in an input-poor EFL environment such as China where textbooks and classrooms are practically the only resources for language input, and high-stakes examinations are the main tools for the evaluation of learning results. Indeed, a look at the 67 most cited articles in CNKI suggests that none of the empirical studies has focused on the strategic learning of implicit knowledge. My point is, in a learning culture that stresses intentional efforts in learning, there is a need for special attention to be paid to the strategic deployment of efforts on not just the explicit knowledge aspect of language (e.g., the meaning, the grammar rules), but also the implicit aspect of language competence. In other words, deliberate, intentional deployment of strategies such as reading for pleasure should be encouraged in order to pick up implicit knowledge such as processing automaticity, contextual nuances in meaning, and depth of vocabulary knowledge.

A related area is in the excessive attention paid to certain aspects of language learning, e.g. vocabulary size (or breadth), that are believed to be both difficult and important. A central core of strategic learning begins with task analysis (Gu, 2012). Deployment of the right strategies only comes after the learner has come to a temporary conclusion that the chosen strategies will help in solving the learning problem at hand and in improving learning outcomes, given the contextual support or constraints, and given the learner’s own strengths, weaknesses, and repertoire of available strategies for similar tasks. Successfulness of implementation will be evaluated against the criteria of task completion and problem solution. Wrong conclusions in task analysis will lead to the deployment of wrong strategies that do not help with the solution of problems in learning.

A case in point is the widespread overuse of memory strategies in China for the learning of vocabulary, partly due to a common erroneous conception of language competence being words plus grammar, and of perceiving the vocabulary learning task as mainly a memory task. Neither researchers nor teachers have paid enough attention to the strategic learning of productive vocabulary. For example, vocabulary learning strategies have received much attention. Nine out of the 67 most cited articles focused on vocabulary learning strategies. Apart from Liu (1999), which compared the spontaneous use of guessing strategies in both English and Chinese and concluded that the ability to guess is related to both English proficiency and ability to guess in Chinese, all other studies were exploratory surveys, and the dependent variable normally involved a passive vocabulary size measure. Given the gravity of the perceived difficulty in vocabulary learning and the research emphasis on passive vocabulary size, it is not surprising that teachers and learners are over-using memory strategies which help increase the number of words learners know. Another example is the over-emphasis on mnemonic devices. Research on mnemonics (e.g., Hulstijn, 1997) has in general shown the usefulness of mnemonic devices in vocabulary learning. However, when we see book-length volumes (e.g., Song, 1989) and TV programmes and multimedia packages (Zhang & Wang, 2007) that provide learners with a bizarre associative link between the English spelling of each word and a Chinese sound-alike word (e.g., DELAY: Landmines/dilei/delayed the enemy’s attack), we know that the research result is being over-applied. Another strategy that is widely researched in vocabulary learning is using word lists and the use of repetition in learning the lists. In fact, even common sense would tell us that repetition is useful in committing a word to memory. However, when we see bookstores full of books that contain nothing but lists of words for memorisation, and see learners doing everything to memorise decontextualized word lists, we know it is overkill, at the expense of other useful strategies for not just the memory but also the depth and automaticity of the words memorised.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

The topic of LLS is now a mature research focus in China, as reflected in the huge number of publications in Chinese journals, and in the number of citations these articles receive. For example, the fact that an early article (Wen, 1995) has been cited almost two thousand times indicate to me both the popularity and the maturity of the research. The overwhelming majority of this research has remained exploratory, finding patterns of strategy use and charting relationships among variables. Strategy training studies are gaining momentum, but most of these studies cater to research rather than pedagogical needs. Likewise, most studies that relate learner autonomy to LS have also been exploratory and correlational. Even the training studies have generally focused on academic rather than practical purposes, and most do not go beyond a language learning framework, without making the leap from the autonomous learner to the autonomous communicator and finally to the autonomous person (Littlewood, 1996). In general, it is sad to see most research findings on LLS not applied or not well applied to language learning. It is perhaps even sadder to see researchers not being aware of the necessity of making their findings applicable in the first place.

Researchers on LLS should do more teacher/learner-friendly research. This involves making research results more readable to classroom teachers and learners. More practical textbooks should be published aiming at integrating LLS research findings into real teaching and learning situations. Teacher-friendly research also involves teachers being encouraged to do their own action research by trying out different ways of LLS intervention. Perhaps a fundamental way of moving this forward is to build LLS into teacher training programmes, so that pre-service and in-service teachers begin to rely more on research findings and less on their own teaching and learning experiences only.

Not all research findings have been shelved. In fact, a few have received too much attention, so much so that there is a real danger that learners and teachers can be misguided as to how a foreign language should be learned. One such example is the over-use of memory strategies. A related issue is the over-use of strategies for explicit knowledge, at the expense of those for implicit aspects of language competence. While it is mainly an issue of selected use of research findings on the part of learners and teachers, as researchers, we cannot shrug off our responsibility of not doing enough to inform those who need our research, and of collective silence in the face of market-hungry profiteers who selectively oversell a few learning gimmicks that may or may not be related to our research findings.

On a more positive note, we now know much better in terms of both a whole repertoire of LLS Chinese students use and the relationship between strategy use and EFL learning results. Strategic learning as an important phenomenon in language learning has received so much attention in China that it has become an important part of the national curriculum and has been included in the textbooks. Despite a lack of clarity and transparency in the selection of LLS and in the guidance for implementation and evaluation, a concrete set of curriculum standards in strategic learning provides at least a basis for teachers and learners to take strategic learning seriously. Given the problem of curriculum implementation, which to a certain extent can be remedied by teacher education, raising the awareness of LLS among teachers and learners and showing some examples of use are certainly a good start. With this level of emphasis and guidance at the top, and the ubiquitous need of learning how to learn at the classroom level, what is left is a re-orientation of research focus from basic research to applied research, from an aim for the advancement of knowledge about strategic language learning only to the ultimate aim of improving language learning results, and empowering language learners.

Brown, H. D. (1991). TESOL at twenty-five: What are the issues?TESOLQuarterly, 25(2), 245-260.

Canagarajah, A. S. (2006). TESOL at forty: What are the issues?TESOLQuarterly, 40, 9-34.

Chamot, A. U., Barnhardt, S., El-Dinary, P. B., & Robbins, J. (1999).Thelearningstrategieshandbook. White Plains, NY: Longman.

Cheng, B. (2006). Daxue yingyu xuexi celue peixun shijian yu xiaoguo fenxi [Effects of learning strategy instruction on College English proficiency].JournalofXi’anInternationalStudiesUniversity, 14(3), 48-50.

Crabbe, D. (1993). Fostering autonomy from within the classroom: The teacher’s responsibility.System, 21(4), 443-452.

Ellis, G. & Sinclair, B. (1989).LearningtolearnEnglish:Learner’sbook. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ge, B. (2006). Guanyu zhongxuesheng yingyu xuexi dongji guannian celue guanxi de yixiang shizheng yanjiu [An empirical study of motivation, beliefs, and learning strategies among secondary school students].ForeignLanguageTeachingAbroad, 1, 14-23.

Gu, Y. (2012). Learning strategies: Prototypical core and dimensions of variation.StudiesinSelf-AccessLearningJournal, 3(4), 330-356.

Gu, Y. (2014). The unbearable lightness of the curriculum: what drives the assessment practices of a teacher of English as a foreign language in a Chinese secondary school?AssessmentinEducation:Principles,Policy&Practice, 21(3), 286-305.

Gu, Y., Hu, G. W., Zhang, J., & Bai, R. (2011).Strategy-basedinstruction:Focusingonreadingandwritingstrategies. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

He, L. & Liu, R. (2004). Jiyu yuliaoku de daxuesheng jiaoji celue yanjiu [A corpus-based study of communication strategies among university students].ForeignLanguagesResearch, 83, 60-65.Hou, Y. & Dai, Z. (2011). Daxue yingyu jiaoxue zhong de xuexi celue zhidao: Xunlian fangshi yu jiaoshi jiaose [Learning strategy guidance in College English teaching: Modes of training and the teacher’s role].TechnologyInformation, 20, 452-453.Hulstijn, J. H. (1997). Mnemonic methods in foreign language vocabulary learning. In J. Coady & T. Huckin (Eds.),Secondlanguagevocabularyacquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 203-224.Institute of Foreign Language Teaching and Teacher Education, Beijing Normal University, Beijing Institute of Curriculum Studies, & The Primary School Integrated Curriculum Reform Experiment Project Team. (2008). Xiaoxue yi zhi san nianji xuesheng yingyu xuexi celue fazhan yanjiu [A study of the development of English learning strategies among Primary 1 to 3 learners].ForeignLanguageTeachinginSchools, 8, 1-6.

Ji, P. & He, M. (2004). Daxue yingyu shisheng tingli celue yanjiu [A survey of listening strategies among College English teachers and learners].ForeignLanguageWorld, 103(5), 40-46.Jin, L. & Cortazzi, M. (1998). The culture the learner brings: A bridge or a barrier. In M. Byram & M. Fleming (Eds.),Languagelearningininterculturalperspective:Approachesthroughdramaandethnography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 98-118.Kumaravadivelu, B. (2003).Beyondmethods:Macrostrategiesforlanguageteaching. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Littlewood, W. (1996). ‘Autonomy’: An anatomy and a framework.System, 24(4), 427-435.Liu, D. & Fu, Y. (2003). Ketang jiaoxue zhong de xuexi celue zhidao [Learning strategy guidance in classroom teaching].JournalofSouthwestChinaNormalUniversity(HumanitiesandSocialSciencesEdition), 29(6), 36-39.

Liu, J. (1999). Waiyu xuexi celue yanjiu: Cai ci nengli yu waiyu shuiping [Foreign language learning strategies: Vocabulary guessing and foreign language competence].ForeignLanguageEducation, 20(3), 31-35.Lu, Z. (2002). Yingyu xuesheng de yuanrenzhi yu xuexi shijian fenpei celue [English learners’ metacognitive strategies for time management].ModernForeignLanguages, 25, 396-407.

Ma, X. & Meng, Y. (2008). Jiyu xuexizhe kekong yinsu de gexinghua yingyu xuexi celue zhenduan yu zhidao xitong yanfa [Developing a diagnostic and counseling system for personalized English learning strategies based on EFL learners’ controllable factors].JournalofPLAUniversityofForeignLanguages, 31(4), 38-42.

Ma Xiaomei Research Team. (2008). Gexinghua yingyu xuexi zhenduan yu zhidao xitong shizheng yanjiu yu xitong jiagou gaiyao [A framework and empirical research for the Personalized English Learning Diagnosis and Advice System].ForeignLanguageTeachingandResearch, 40(3), 184-187.

Meng, Y. (2004). Daxue yingyu yuedu celue xunlian de shiyan yanjiu [An experimental study of reading strategies training at the tertiary level].ForeignLanguagesandTheirTeaching, 179, 24-27.

MOE China. (2001).Englishlanguagecurriculumstandardsforfull-timecompulsoryeducationandseniorsecondaryschools(Trialversion). Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press.

MOE China. (2003).Englishlanguagecurriculumstandardsforseniorsecondaryschools(Experimental). Beijing: People’s Education Press.

MOE China. (2010). Education statistics 2009. Retrieved January 5, 2012, from http:∥www.moe.edu.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/moe/s4959/index.html

MOE China. (2011).Englishcurriculumstandardsforcompulsoryeducation,Version2011. Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press.

Oxford, R. L. (2011).Teachingandresearchinglanguagelearningstrategies. Harlow: Pearson Longman.

Pennycook, A. (1997). Cultural alternatives and autonomy. In P. Benson & P. Voller (Eds.),Autonomyandindependenceinlanguagelearning. New York: Longman, 35-53.

Rubin, J. (1975). What the ‘good language learner’ can teach us.TESOLQuarterly, 9(1), 41-51.

Si, J., Zhao, J., & He, M. (2005). Zhongguo gaozhi xuesheng yingyu xuexi celue diaocha [A survey of English language learning strategies among vocational school students].ForeignLanguageTeachingAbroad, 1, 23-27, 7.

Smith, R. C. (2003). Pedagogy for autonomy as (becoming-) appropriate methodology. InLearnerautonomyacrosscultures:Languageeducationperspectives. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 129-146.

Song, Y. (1989).Fengbaomishiyingyudancisujifa[ThestormpuzzlemethodofacceleratedEnglishvocabularylearning]. Beijing: Popular Science Press.Stern, H. H. (1975). What can we learn from the good language learner?CanadianModernLanguageReview, 31, 304-318.

Wang, F. (2011). Chuzhong yingyu jiaoshi xuexi celue zhidao de xianzhuang diaocha [A survey of middle school English teachers’ learning strategy guidance].CollectedPapersinScienceandTechnology, 5, 154-155.

Wang, L. (2002). Daxuesheng yingyu kouyuke jiaoji celue jiaoxue de shiyan baogao [Teaching communication strategies in spoken English classes at the tertiary level].ForeignLanguageTeachingandResearch, 34, 426-430.

Wang, Q. & Editorial team (Eds.). (2009a).SeniorHighEnglish—Module4:Studentbook. Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press; Pearson Education.

Wang, Q. & Editorial team (Eds.). (2009b).SeniorHighEnglish—Module4:Teacher’sbook. Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press; Pearson Education.

Wang, X. & Yin, T. (2003). Yingyu xuexi celue xitong juedingxing yinsu de shizheng yanjiu [An empirical study of the factors affecting English language learning strategies].ForeignLanguageResearch, 115, 99-102.Wen, Q. (1995). Yingyu xuexi chenggongzhe yu bu chenggongzhe zai fangfa shang de chayi [Learning strategy differences between successful and non-successful English language learners].ForeignLanguageTeachingandResearch, 92(3), 61-66.

Wen, Q. (2001). Yingyu xuexizhe dongji guannian celue de bianhua guilu ye dedian [Developmental patterns in motivation, beliefs and strategies of English learners in China].ForeignLanguageTeachingandResearch, 33(2), 105-110.Wen, Q. & Wang, L. (2004a). Dui waiyu xuexi celue youxiaoxing yanjiu de zhiyi [On the effectiveness of foreign language learning strategies].ForeignLanguageWorld, 100, 2-7, 28.

Wen, Q. & Wang, L. (2004b). Yingxiang waiyu xuexi celue xitong yunxing de gezhong yinsu pingshu [Factors in the effective use of foreign language learning strategies].ForeignLanguagesandTheirTeaching, 186, 28-32.Xiang, J. (2010). Chuzhong yingyu jiaoxue shentou xuexi celue zhidao de tansuo [Strategy-based instruction in the teaching of English in junior secondary schools].Examinination,TeachingandResearch, 12, 58-60.

Xu, J., Peng, R., & Wu, W. (2004). Fei yingyu zhuanye daxuesheng zizhuxing yingyu xuexi nengli diaocha yu fenxi [A survey of learner autonomy among non-English majors].ForeignLanguageTeachingandResearch, 36, 64-68.

Yang, J. (2003). Tingli jiaoxue zhong de yuanrenzhi celue peixun [Metacognitive strategy training in the teaching of listening].ForeignLanguageEducation, 24(4), 65-69.Yang, S. (2002). Yingyu xiezuo chenggongzhe yu bu chenggongzhe zai celue shiyong shang de chayi [Successful and non-successful writers and their use of writing strategies].ForeignLanguageWorld, 89, 57-64.

Yao, M. (2000). Dangqian waiyu cihui xuexi celue de jiaoxue yanjiu quxiang [Teaching and research trends on vocabulary learning strategies].JournalofBeijingNormalUniversity(HumanitiesandSocialSciences), 161(5), 123-129.

Zhang, X. (2005). Jichu jieduan yingyu zhuanye xuesheng yuanrenzhi celue diaocha [A survey of metacognitive strategies among English majors at the foundation stage].JournalofPLAUniversityofForeignLanguages, 28(3), 59-62.

Zhang, J. & Wang, M. (2007). Danci buyong ji 3.0 [Words don’t need to be memorised Ver. 3]. Sun Yat-sen University Press (Multimedia).

10.3969/j.issn.1674-8921.2014.12.001

Correspondence should be addressed to Yongqi Gu, School of Linguistics and Applied Language Studies at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. Email: peter.gu@vuw.ac.nz

- 當代外語研究的其它文章

- How to Make L2 Easier to Process? The Role of L2 Proficiency andSemantic Category in Translation Priming

- Call For Papers

- A Meta-analysis of Cross-linguistic Syntactic Priming Effects

- Effects of Explicit Focus on Form on L2 Acquisition of EnglishPassive Construction

- Development of Implicit and Explicit Knowledge of GrammaticalStructures in Chinese EFL Learners

- Extending the Distributional Bias Hypothesis to the Acquisition ofHonorific Morphology in L2 Korean