Physiological Testosterone Retards Cardiomyocyte Aging in Tfm Mice via Androgen Receptor-independent Pathway△

Li Zhang,Da Lei,Gui-ping Zhu,Lei Hong,and Sai-zhu Wu*

1Department of Cardiology,First Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Pharmaceutical University,Guangzhou 510080,China

2Department of Cardiology,Nanfang Hospital,Southern Medical University,Guangzhou 510515,China

TESTOSTERONE is the major androgen and deficiency in its circulating levels is a prominent feature observed in aging males.Testosterone exerts a variety of anabolic and androgenic effects on many organs,most of which are mediated by the nuclear androgen receptor (AR).AR is expressed in mammalian and primate cardiomyocytes,suggesting that androgens may play a role in the heart.1Reduced androgen levels have been associated with aging-related cardiovascular diseases and testosterone replacement therapy may have some benefits for cardiovascular function.2Furthermore,in experimental rats with low testosterone levels,physiological testosterone therapy can improve the reduced cardiac functional capacity,probably by inhibiting tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α),3which is a pro-inflammatory cytokine closely linked to the aging process.4In addition to the AR pathway,the beneficial effect of long-term testosterone on cardiomyocytes may be attributed to its conversion to estradiol through aromatase activity.5These findings have led to the hypothesis that testosterone has a mitigating impact on the aging process of the cardiovascular system.

With aging,cardiac function is organically and cellularly impaired.Cardiomyocytes,as the major components of the contractile apparatus,undergo a number of physiological and morphological changes in that process,and these changes are thought to contribute to cardiac function reduction and heart diseases.4It is suggested that cardiomyocyte aging is initiated by oxidative stress,and that mutations and changes in gene expression are the central elements in“memorization”and progression of aging.4The present study investigated the effect of low testosterone levels and physiological testosterone therapy on oxidative stress and aging-associated gene expression in murine cardiomyocytes.Furthermore,whether testosterone therapy modulating cardiomyocyte agingviathe classical AR-dependent pathway or conversion to estradiol was discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals

All the experimental procedures in this study were approved by the Animal Research Committee of Nanfang Hospital,Southern Medical University.Breeder mice were purchased from the Model Animal Research Center of Nanjing University (female,AW-J/AW-JEdaTa-6J+/+ArTfm;male,AW-J/AW-JEdaTa-6J+/Y).Male littermates and the testicular feminized (Tfm) mice were bred in the Laboratory of Cardiovascular Disease,Southern Medical University.The gender of the Tfm mice was determined with polymerase chain reaction.Tfm mice exhibit an X-linked,single-base-pair deletion in the AR-encoding gene.This deletion results in premature termination of AR protein synthesis,which in turn leads to the production of non-functional AR.6In addition,circulating levels of testosterone are reduced in the Tfm mice,approximately 90% lower compared to their male littermates.7

At 12 weeks of age,8 male littermates and 22 Tfm mice were grouped for separate treatment.Briefly,the Tfm mice were randomly divided into 3 groups using computer software.The mice then received intramuscular injection of saline (male littermates,control,n=8;Tfm,n=7),testosterone propionate injection (Tfm+T,n=8),and testosterone propionate injection in combination with 10 mg/(kg·d) of aromatase inhibitor anastrazole in drinking water7(AstraZeneca,London,UK;Tfm+T+A,n=7).Testosterone propionate was injected at 3 mg/kg,diluted in sesame oil,once every 72 hours for 3 months.

Pharmacokinetic determination of physiological testosterone levels

To establish and maintain a dosing regimen of testosterone at physiological levels,we first determined the appropriate volume and frequency of administration of 25 mg/mL testosterone propionate.Twelve-week-old Tfm mice (n=33)received a single 3 mg/kg intramuscular injection of testosterone propionate (the human replacement dose of testosterone propionate is 0.35 mg/kg administered 2-3 times per week according to manufacturer’s instructions).The mice were sacrificed at 0,0.5,1,2,4,8,16,24,32,48,and 72 hours after injection (n=3 at each time point) for the measurement of testosterone concentrations in duplicate [enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)kits,R&D Systems,Inc.,Minneapolis,MN,USA].To ensure reproducibility,18 additional Tfm mice received a second-cycle injection (double administration) 72 hours after the first cycle and were sacrificed at 1,2,4,8,24,and 72 hours after the second injection (n=3 at each time point).In order to determine normal testosterone concentrations,9 male littermates were sacrificed at 0∶00,8∶00,and 16∶00.

Isolation of cardiomyocytes

Left ventricular myocytes were enzymatically isolated from the 30 grouped mice as previously described.8The solutions were supplements of modified commercial minimal essential medium (MEM) Eagle-Joklik.The washing solution contained HEPES-MEM added with 0.5 mmol/L ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA).The resuspension medium contained HEPES-MEM supplemented with 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.3 mmol/L CaCl2.Briefly,the hearts were quickly removed and connected to a plastic cannula for retrograde perfusion through the aorta.The cell isolation procedure consisted of 3 main steps∶(1) for low-calcium perfusion,blood washout in the presence of EGTA was performed for about 10 minutes,and collagenase (selected type I,Worthington Biochemical Corp.,Lakewood,NJ,USA) perfusion of the myocardium was carried out at 37°C with HEPES-MEM gassed with 85% O2and 15% N2;(2) the heart was removed from the cannula,the left ventricle was cut into small pieces (1 mm3) and subsequently shaken in resuspension medium at 37°C,supernatant cell suspensions were washed and resuspended in resuspension medium;(3) intact cells were enriched by centrifugation at 8 000 ×gfor 2 minutes.This procedure was repeated 4-5 times.

Preparation of homogenates

Freshly isolated cardiomyocytes (5×106) were mixed with 1 mL of cell lysis solution,repeatedly pipetted and sonicated in ice.In order to eliminate debris,the crude homogenate was centrifuged at 6 700 ×gfor 10 minutes at 4°C.The supernatant was used for the assay of superoxide dismutase (SOD),glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px),and malondialdehyde (MDA).

Assay of antioxidant enzyme activity and MDA levels

The activities of SOD and GSH-Px were determined using assay kits (Jian Cheng Biology Research Center,Nanjing,China).SOD activity was measured through the inhibition of nitroblue tetrazolium reduction by O2-generated by the xanthine/xanthine oxidase system.One unit of SOD activity was defined as the amount of enzyme causing 50%inhibition in 1 mL reaction solution.GSH-Px activity was measured by using H2O2and GSH as substrates.One unit of GSH-Px activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to degrade 1 mmol/L of GSH per minute subtracting the degradation by non-enzymatic reaction.Each end-point assay was monitored using absorbance at 550 nm in SOD activity and at 412 nm in GSH-Px activity.The enzyme activities are expressed as U/mL.

MDA levels were determined with thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay using a MDA assay kit(Jian Cheng Biology Research Center).TBARS is widely used to quantify the lipid peroxidation caused by high reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels.Each end-point assay was monitored using absorbance at 532 nm and the results are expressed as nmol/mL.

Western blotting

Freshly isolated cardiomyocytes were lysed in 250 μL lysis buffer (50 mmol/L Tris-HCl,pH 7.5,5 mmol/L ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid,250 mmol/L NaCl,and 0.1%Triton X-100) containing protease inhibitors (2 mmol/L phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride,1 μg/mL aprotinin,5 mmol/L dithiothreitol,and 1 mmol/L Na3VO4).The cardiomyocyte lysates were centrifuged at 6700 ×gfor 10 minutes.Protein (40 μg) was separated with 10%-15%sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad Life Science,Hercules,CA,USA).After blocking with 5% BSA for 1 hour,the membranes were incubated overnight with primary antibody dilution buffer at 4°C.Anti-p16INK4α(F-12,Santa Cruz Biotechnology,Inc.,Dallas,TX,USA),and anti-unphosphorylated Rb (Wuhan Boster Co.,Wuhan,China)were used.Horse radish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and goat anti-rabbit (Bio-Rad Life Science) served as the secondary antibodies.The membranes were briefly incubated with electrochemiluminescence detection reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.,Waltham,MA,USA) to visualize the proteins and exposed to X-ray film.β-actin (Wuhan Boster Co.) was used as an internal control.The data of Western blotting in this study were from at least 3 independent experiments.

Measurement of testosterone concentration

At the time of measurements,blood was collected without anticoagulant from the retroorbital venous plexus.Samples were centrifuged at 1400 ×gfor 10 minutes,serum was collected and stored at -20°C until assay.Total testosterone levels were measured in duplicate using commercially available ELISA kits (R&D Systems,Inc.).Inter-assay variation was 2.9%-4.0% and intra-assay variation was 5.6%-6.8%.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 13.0.Data are reported as means±SD,analyzed using one-way analysis of variance,with equal variances assumed with the least significant difference test and not assumed with Dunnett’s T3 multiple comparisons.The level of significance was set at α=0.05.

RESULTS

Dosing regimen to physiological testosterone levels in Tfm mice

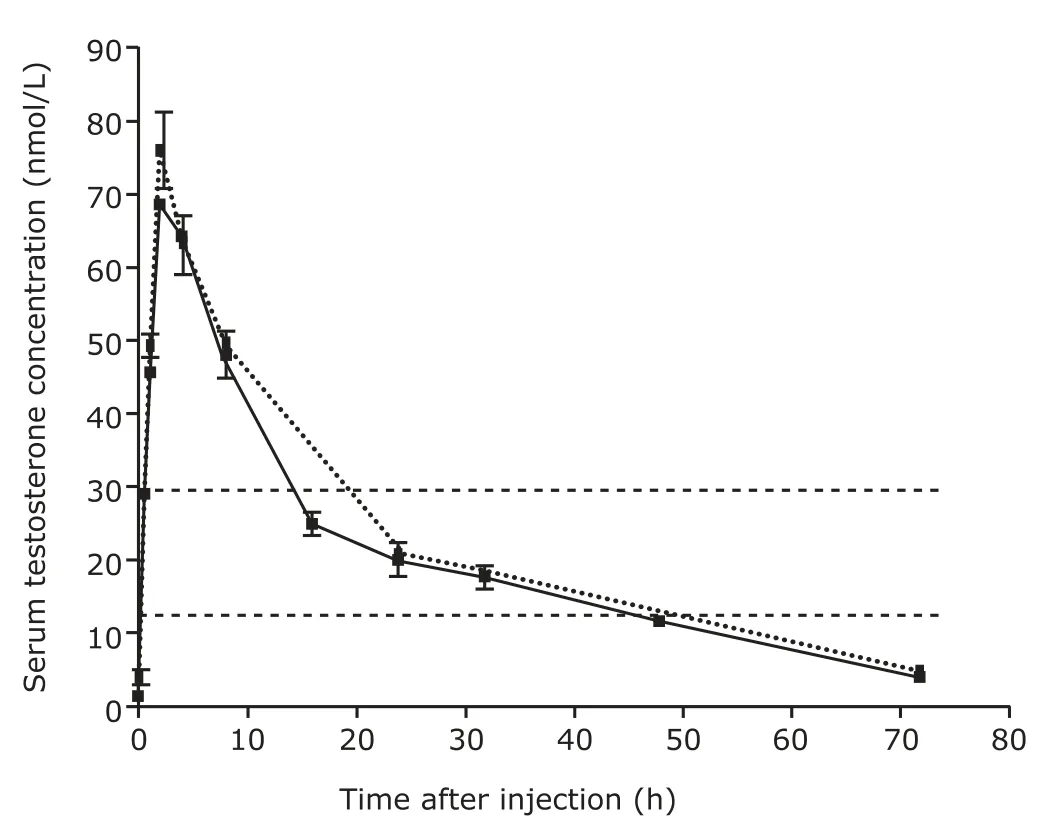

The normal range of testosterone concentrations in male littermates was 11.3-30.2 nmol/L.Baseline levels of serum testosterone in Tfm mice were 12% of the normal levels.The levels rose significantly after intramuscular injection of 3 mg/kg testosterone at 0.5 hour,reached a peak at 2 hour,and remained within the normal range between 14 and 50 hours (Fig.1).The mean area under the curve (AUC) for the first 72-hour period was 19.8 nmol/L and the mean AUC for the second 72-hour period was 20.9 nmol/L.Pharmacokinetics showed no statistical difference in the peak time,AUC,or testosterone concentrations between single and double cycles of injection.Furthermore,after both cycles of injection,the mean AUC were all within the normal range.

Figure 1.Pharmacokinetic curves of testosterone concentrations after single and double 72-hour cycles of testosterone propionate injection in testicular feminized (Tfm) mice.The testosterone levels in Tfm mice receiving a single 3 mg/kg intramuscular injection of 25 mg/mL testosterone were measured at 0,0.5,1,2,4,8,16,24,32,48,and 72 hours after injection (n=3 at each time point,the solid line).An additional 3 mg/kg intramuscular injection of 25 mg/mL testosterone was administered 72 hours after the first injection,and the testosterone levels were measured at 1,2,4,8,24,and 72 hours after the second injection (n=3 at each time point,the dashed line).The area between the parallel dotted lines indicates the physiological range of testosterone concentration measured with male littermates(11.3-30.2 nmol/L,n=9).

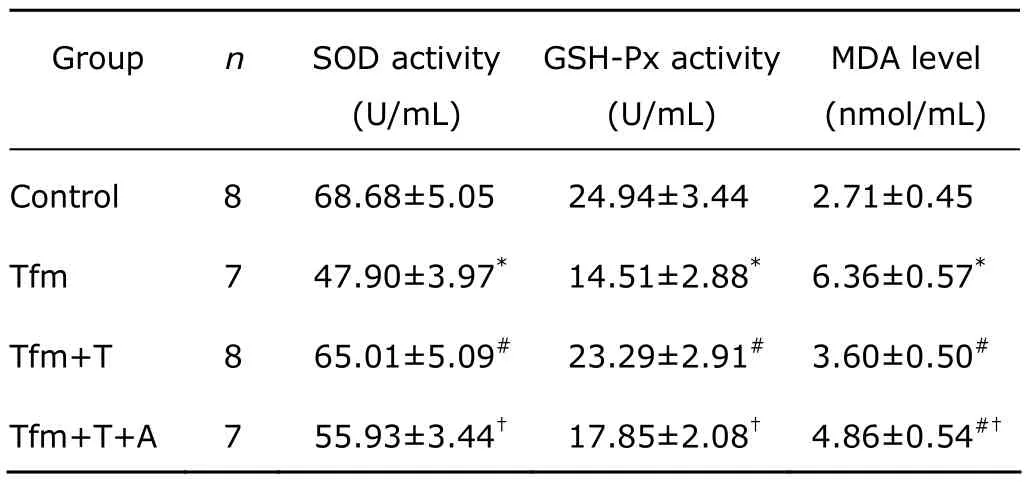

Antioxidant enzyme activity and MDA levels

Significant decreases of the SOD and GSH-Px specific activities were observed in cardiomyocytes isolated from Tfm mice compared with the age-matched control group(SOD,P=0.002;GSH-Px,P=0.000).In Tfm mice receiving testosterone propionate injection,SOD and GSH-Px activities increased significantly compared with untreated Tfm mice (SOD,P=0.006;GSH-Px,P=0.002).The SOD and GSH-Px activities were significantly lower in Tfm mice receiving testosterone in combination with anastrazole than in those receiving testosterone alone (SOD,P=0.048;GSH-Px,P=0.037);and higher than in untreated Tfm mice,but the differences did not reach the level of significance(Table 1).

A significant increase in the MDA level was found in Tfm mice compared with the age-matched control group(P=0.000).In the Tfm mice injected with testosterone propionate,MDA level decreased significantly compared with that in untreated Tfm mice (P=0.000).The MDA level was significantly higher in the Tfm mice receiving testosterone in combination with anastrazole than in those receiving testosterone alone (P=0.018),but still lower than in untreated Tfm mice (P=0.007,Table 1).

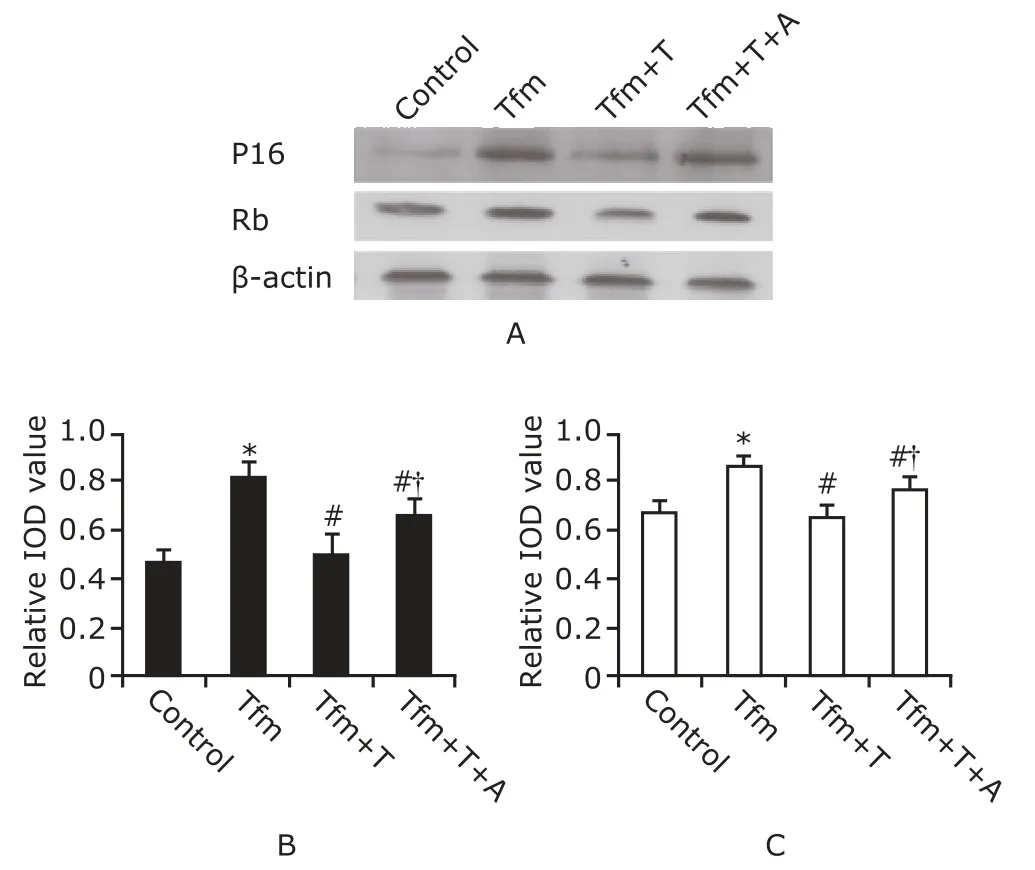

Expressions of p16INK4α and Rb proteins

Expressions of p16INK4αand Rb proteins were low in the control group (Fig.2).The expression levels were significantly higher in Tfm mice than in control mice(p16INK4α,P=0.001;Rb,P=0.002).The expression levels of p16INK4αand Rb proteins were significantly lower in the Tfm mice with testosterone injection than in untreated Tfm mice (bothP=0.001).The expression levels of p16INK4αand Rb proteins were significantly higher in the Tfm mice receiving*testosterone in combination with anastrazole than in those receiving testosterone alone (p16INK4α,P=0.039;Rb,P=0.027),but still lower than in untreated Tfm mice (p16INK4α,P=0.048;Rb,P=0.026).

Table 1.The enzyme activities of SOD and GSH-Px,and the level of MDA in cardiomyocytes§

Figure 2.Western blotting of p16INK4α and Rb proteins in cardiomyocytes (A).Densitometric analysis of p16INK4α protein(B) and Rb protein (C).Data are reported as means±SD.IOD∶integrated optical density.

DISCUSSION

Cardiomyocytes are rich in mitochondria,which can provide rapid and substantial ATP production to meet the energy demands for increased work.However,this boosted energy production can lead to an increased ROS generation that may surmount antioxidant defenses and lead to the intrinsic generation of oxidative stress,4a typical aging factor.Both enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant defenses protect the cell from ROS.9The cellular antioxidant defense system consists of SOD,GSH-Px,and other related enzymes.10This dynamic system must be precisely regulated in order to protect cells from oxidative damage.Membrane lipids are vulnerable to peroxidation by oxidants,forming MDA in this process;therefore the level of MDA could serve as an indicator of oxidative damage.

Senescent cardiomyocytes are characterized by an irreversible cell cycle arrest,which is mediated and indicated by an up-regulation of p16INK4αand p53.4Kajsturaet al11reported that the proportion of p16INK4αpositive myocytes increased with age.Torella et al8found that the expression of p16INK4αand p53 increased with age in cardiomyocytes of wild-type mice.Hypophosphorylated Rb was predominant in aging wild-type cardiomyocytes,reflecting the up-regulation of p16INK4α.Similarly,Maejimaet al12found the mRNA levels of p16INK4αand acetylated p53 increased in aged rat cardiomyocytes.

The present study revealed that the left ventricular myocytes from Tfm mice had decreased SOD and GSH-Px activities,increased MDA levels,and increased expressions of p16INK4αand Rb proteins compared with the male littermates (control),suggesting that testosterone deficiency contributes to cardiomyocyte aging,consistent with the results reported by Barpet al,13K?apcińskaet al14in hearts and Meydanet al10in the hippocampus.In agreement with our findings on MDA levels,previous studies found that castration leads to higher MDA content14and an increase in lipid peroxidation15in the left ventricle.To our knowledge,few researches explore the direct association between testosterone levels and the expressions of p16INK4αand Rb proteins.

Furthermore,we observed that the aging of cardiomyocytes was ameliorated with physiological testosterone therapy as indicated by increased SOD and GSH-Px enzyme activities,reduced MDA levels,and lowered expressions of p16INK4αand Rb proteins.Evidence regarding the potential antioxidant role of exogenous testosterone in the heart is very scarce,and conflicting results have been observed in different tissues.K?apcińskaet al14reported that testosterone replacement in castrated rats exacerbated the decline in myocardium antioxidant defense,including SOD and GSH-Px activities.In contrast,exogenous testosterone increased SOD and GSH-Px enzyme activities in the hippocampus,which were reduced after castration.10It has been reported that testosterone administration leads to a decrease in MDA levels in rat liver and brain.10,16In the study by Sreelatha Kumariet al,15administration of testosterone in castrated rats partially reversed the increase in lipid peroxidation in the hearts.However,K?apcińskaet al14found that testosterone replacement in castrated male rats led to a further increase in MDA levels in the left ventricle.The discrepancies may be attributed to the fact that those experiments were performed using tissue lysates,in which other cell types were present and could mask the changes in ventricular cardiomyocytes.It is probable that the effect of testosterone is tissue-dependent.17Luet al18showed that androgen down-regulated the expression of the cyclindependent kinase inhibitor p16INK4αgene in LNCaP-FGC cells.In the study conducted by Gregoryet al,19the hypophosphorylated Rb was down-regulated by testosterone propionate treatment in castrated mice.

Another finding of the present study was a positive effect of testosterone on cardiomyocyte aging independent of AR,because the Tfm mice expressing non-functional AR still responded to exogenous testosterone.Furthermore,increased SOD and GSH-Px enzyme activities,decreased MDA levels,and down-regulated expressions of p16INK4αand Rb proteins in testosterone-treated Tfm mice were significantly inhibited by co-treatment with anastrazole,an aromatase inhibitor.The degree of cardiomyocyte aging in the Tfm mice treated with the combination of testosterone and anastrazole,however,was still lower than in Tfm mice,in regards of MDA levels and expressions of p16INK4αand Rb proteins.These data demonstrated that physiological testosterone ameliorates cardiomyocyte aging partlyviaaromatization to estradiol in cardiac myocytes.Michelset al5reported that the long-term effect of testosterone on single T-type calcium channel was mediated in partviathe estrogen pathway in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes.Co-incubation of rat cardiomyocytes with testosterone and the specific aromatase inhibitor showed an inhibition of estrogenresponsive element activation,but this was not observed in cells incubated with testosterone alone,implicating that conversion to estradiol is the mechanism underlying the action of testosterone in cardiomyocytes.

In conclusion,testosterone deficiency contributes to cardiomyocyte aging in Tfm mice and the beneficial effect of physiological testosterone on aging cardiomyocytes may be independent of the classical AR pathway and mediated in part by conversion to estradiol.However,further investigations are needed before these results can be extrapolated from mice to humans.

1.Golden KL,Marsh JD,Jiang Y,et al.Gonadectomy alters myosin heavy chain composition in isolated cardiac myocytes.Endocrine 2004;24∶137-40.

2.Gooren LJ.Androgens and male aging∶current evidence of safety and efficacy.Asian J Androl 2010;12∶136-51.

3.Li ZB,Wang J,Wang JX,et al.Testosterone therapy improves cardiac function of male rats with right heart failure.Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue 2009;15∶994-1000.

4.Bernhard D,Laufer G.The aging cardiomyocyte∶a mini-review.Gerontology 2008;54∶24-31.

5.Michels G,Er F,Eicks M,et al.Long-term and immediate effect of testosterone on single T-type calcium channel in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes.Endocrinology 2006;147∶5160-9.

6.Jones RD,Pugh PJ,Hall J,et al.Altered circulating hormone levels,endothelial function and vascular reactivity in the testicular feminised mouse.Eur J Endocrinol 2003;148∶111-20.

7.Nettleship JE,Jones TH,Channer KS,et al.Physiological testosterone replacement therapy attenuates fatty streak formation and improves high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in the Tfm mouse∶an effect that is independent of the classic androgen receptor.Circulation 2007;116∶2427-34.

8.Torella D,Rota M,Nurzynska D,et al.Cardiac stem cell and myocyte aging,heart failure,and insulin-like growth factor-1 overexpression.Circ Res 2004;94∶514-24.

9.Park CJ,Park SA,Yoon TG,et al.Bupivacaine induces apoptosis via ROS in the Schwann cell line.J Dent Res 2005;84∶852-7.

10.Meydan S,Kus I,Tas U,et al.Effects of testosterone on orchiectomy-induced oxidative damage in the rat hippocampus.J Chem Neuroanat 2010;40∶281-5.

11.Kajstura J,Pertoldi B,Leri A,et al.Telomere shortening is anin vivomarker of myocyte replication and aging.Am J Pathol2000;156∶813-9.

12.Maejima Y,Adachi S,Ito H,et al.Induction of premature senescence in cardiomyocytes by doxorubicin as a novel mechanism of myocardial damage.Aging Cell2008;7∶125-36.

13.Barp J,Araújo AS,Fernandes TR,et al.Myocardial antioxidant and oxidative stress changes due to sex hormones.Braz J Med Biol Res 2002;35∶1075-81.

14.K?apcińska B,Jagsz S,Sadowska-Krepa E,et al.Effects of castration and testosterone replacement on the antioxidant defense system in rat left ventricle.J Physiol Sci 2008;58∶173-7.

15.Sreelatha Kumari KT,Menon VP,Leelamma S.Testosterone and lipid peroxide metabolism in orchidectomised rats.Indian J Exp Biol 1993;31∶323-6.

16.Guzmán DC,Mejía GB,Vázquez IE,et al.Effect of testosterone and steroids homologues on indolamines and lipid peroxidation in rat brain.J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2005;94∶369-73.

17.Alonso-Alvarez C,Bertrand S,Faivre B,et al.Testosterone and oxidative stress∶the oxidation handicap hypothesis.Proc Biol Sci 2007;274∶819-25.

18.Lu S,Tsai SY,Tsai MJ.Regulation of androgen-dependent prostatic cancer cell growth∶androgen regulation of CDK2,CDK4,and CKI p16 genes.Cancer Res1997;57∶4511-6.

19.Gregory CW,Johnson RT Jr,Presnell SC,et al.Androgen receptor regulation of G1 cyclin and cyclin-dependent kinase function in the CWR22 human prostate cancer xenograft.J Androl2001;22∶537-48.

Chinese Medical Sciences Journal2013年2期

Chinese Medical Sciences Journal2013年2期

- Chinese Medical Sciences Journal的其它文章

- Unsuspected Gallbladder Cancer During or After Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

- Ureteral Stent Fragmentation:a Case Report andReview of Literature

- Blood Lead Levels During Pregnancy and Its Influencing Factors in Nanjing,China

- Introduction of Management of Prostate Cancer:a Multidisciplinary Approach

- Chinese Herbal Medicine in Treatment of Polyhydramnios: a Meta-analysis and Systematic Review△

- Open Surgical Insertion of Tenkchoff Straight Catheter Without Guide Wire