Iron supplementation during malaria infection in pregnancy and childhood: A review

Neha Surela,Amrendra Chaudhary,Poonam Kataria,Jyoti Das

National Institute of Malaria Research,Sector-8,Dwarka,New Delhi-110077,India

ABSTRACT Malaria presents a significant global public health challenge,with severe malarial anaemia being a primary manifestation of the disease.The understanding of anaemia caused by malaria remains incomplete,making the treatment more complex.Iron is a crucial micronutrient essential for haemoglobin synthesis,oxygen delivery,and other vital metabolic functions in the body.It is indispensable for the growth of human beings,as well as bacteria,protozoa,and viruses in vitro and in vivo.Iron deficiency is among the most common nutritional deficiencies and can have detrimental effects during developmental stages of life.Malaria-induced iron deficiency occurs due to the hemolysis of erythrocytes and the suppression of erythropoiesis,leading to anaemia.Meeting iron requirements is particularly critical during pivotal life stages such as pregnancy,infancy,and childhood.Dietary intake alone may not suffice to meet adequate iron requirements,thus highlighting the vital role of iron supplementation.While iron supplementation can alleviate iron deficiency,it can exacerbate malaria infection by providing additional iron for the parasites.However,in the context of pregnancy and childhood,iron supplementation combined with malaria prevention and treatment has been shown to be beneficial in improving birth outcomes and ensuring proper growth and development,respectively.This review aims to identify the role and impact of iron supplementation in malaria infection during the life stages of pregnancy and childhood.

KEYWORDS: Iron supplementation;Malaria;Pregnancy;Childhood

1.Introduction

Iron is the second most prevalent metal in the earth’s crust[1].It is an essential micronutrient vital for the growth and survival of human beings and all bacteria,protozoa,and viruses.Malaria,an infectious disease caused by the protozoa Plasmodium parasite,relies on iron to proliferate during the disease phase and the silent liver stage of the erythrocyte infection.When iron status is low,it confers protection from malaria infection,which makes the relationship between malaria and iron complex in human survival during malaria infection[2].Across the globe,over 37% of pregnant women and 40% of children less than five years are affected by iron deficiency[3].Malaria is a global health problem,with 247 million cases worldwide in 2021 resulting in 619 000 deaths[4].This review discusses the detrimental as well as beneficial effects of iron supplementation (2005-2023)in malaria infection during pregnancy and childhood.The search strategy used for this review includes PubMed and Google Scholar searches between June 2021 and May 2023 with search terms “Malaria during Pregnancy”,“Malaria during Childhood”,“Malarial Anaemia Mechanism” and “Malaria and iron supplementation” (Figure 1).

2.Malarial anaemia mechanism

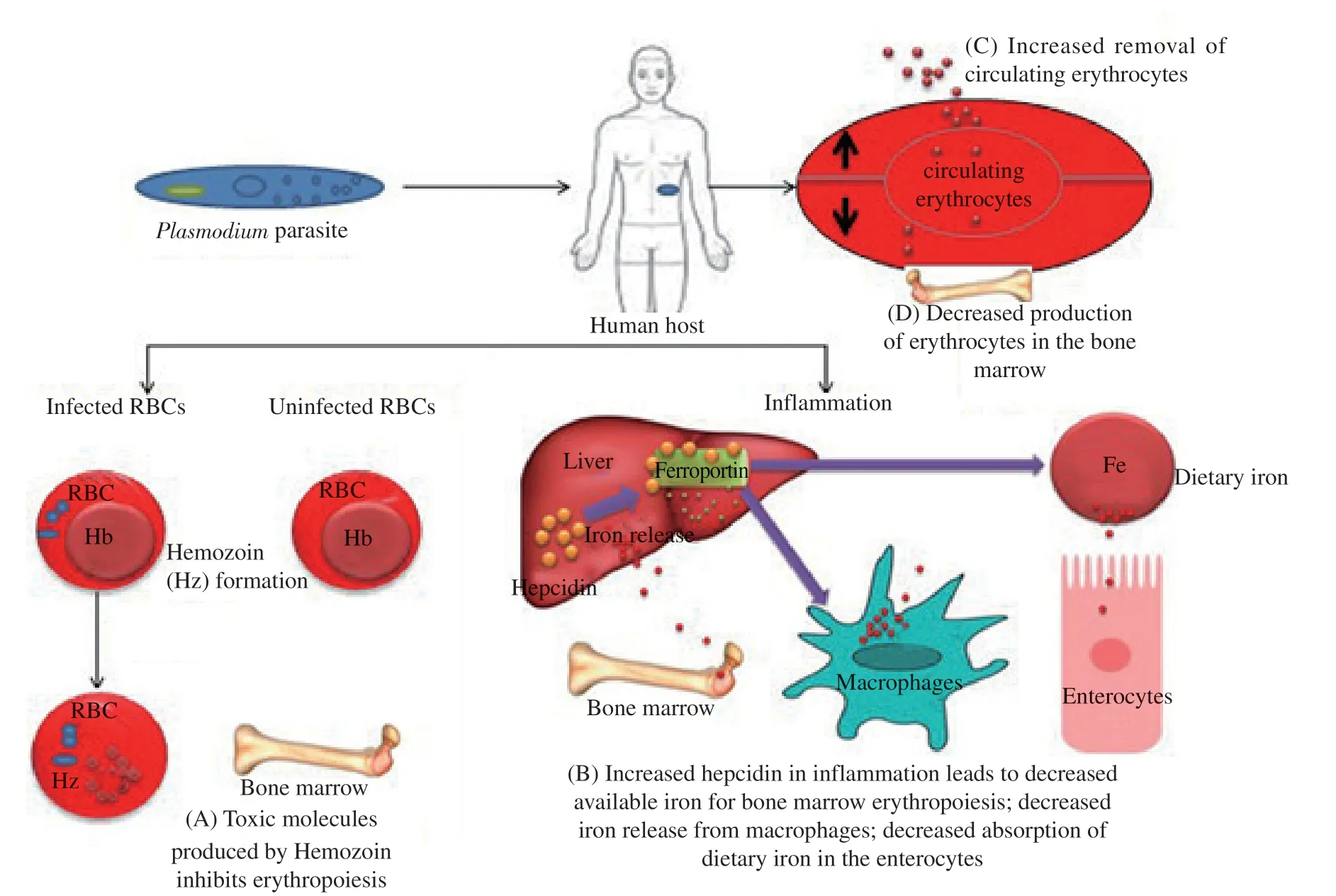

The mechanism of malarial anaemia is complex.Malaria infection leads to ineffective erythropoiesis and dyserythropoiesis,as well as hemolysis of infected and uninfected erythrocytes/RBCs(red blood cells) (Figure 2).Replenishing erythrocytes/RBCs lost by hemolysis is difficult due to poor erythroid response and suppression of erythropoiesis.The loss of erythrocytes in malaria is due to parasite maturation (observed in infected erythrocytes)and antibody sensitization,physiochemical membrane changes and increased reticuloendothelial activity in spleen (observed in uninfected erythrocytes)[5,6].There is accumulation of malarial pigment hemozoin in the bone marrow and altered production of inflammatory mediators (tumor necrosis factor and nitric oxide),which suppress erythropoiesis by direct and indirect acting on erythroid cells[7].Toxic molecules produced by hemozoin inhibit erythropoiesis[8].

Figure 2.Malarial anaemia mechanism: Plasmodium parasite enters human host and (A) infects human RBCs which leads to degradation or digestion of hemoglobin into hemozoin[8].(B) Hepcidin production is increased during malaria infection/inflammation which acts on ferroportin,the sole iron transporter,which leads to decreased iron absorption from dietary iron,and decreased iron release from liver and macrophages,therefore,rendering decreased availability of iron for bone marrow erythropoiesis.(C) while there is decreased production of erythrocytes in the bone marrow,there is increased removal of circulating erythrocytes[9].RBC: Red blood cells;Hb: Hemoglobin;Hz: Hemozoin.

3.Iron and malaria during pregnancy

Each year,over 125 million women are at risk of malaria[10].One of the factors responsible for iron deficiency and anaemia is the low intake of dietary iron.To compensate for iron deficiency in the diet,iron supplementation programs are implemented worldwide to benefit pregnant women and children.However,the relationship between iron and malaria,is controversial in malaria endemic regions and thus impedes the widespread implementation of iron supplementation[11].A study conducted using data from 19 endemic malaria countries,which included analysis of 101 636 singleton live-birth deliveries in the sub-Saharan Africa,showed that mothers who received intermittent-preventive treatment with sulphadoxinepyrimethamine along with iron-folic acid supplementation had less neonatal death as compared to mothers who did not receive either of these.This result was not observed among mothers who received only intermittent-preventive treatment with sulphadoxinepyrimethamine or iron-folic acid supplementation.Therefore,we can conclude that iron supplementation and malaria prophylaxis are associated with better maternal and infant outcomes.However,in malaria endemic areas,when iron supplementation with folic acid is given in the absence of malaria prophylaxis,it increases the risk of malaria morbidity[12-14].

3.1.Increased iron needs and the role of hepcidin

Anaemia during pregnancy may lead to maternal mortality and stillbirth,which necessities increased requirements during pregnancy[14].It is estimated that 450 mg iron is required to support the erythropoiesis and red cell mass expansion essential for the normal growth of the placenta and the fetus.Hepcidin,the main iron regulatory hormone,acts on ferroportin which inhibits (when stimulated) or allows (when suppressed) the oral iron absorption and release of iron from macrophages and the liver (Figure 2).During pregnancy,iron absorption increases due to the suppression of the hormone hepcidin[15].However,in the cases of infection or inflammation during pregnancy,the hepcidin hormone is stimulated,inhibiting iron absorption.Hence,iron sufficiency may not be met through dietary sources,if the diet is plant-based with limited bioavailability of iron due to phytates and polyphenols[15,16].Therefore,iron supplementation is required during pregnancy to meet the additional iron requirements.Maternal iron supplementation results in improved birth weight and iron stores in the newborn[17,18].

3.2.Iron deficiency protects against malaria infection

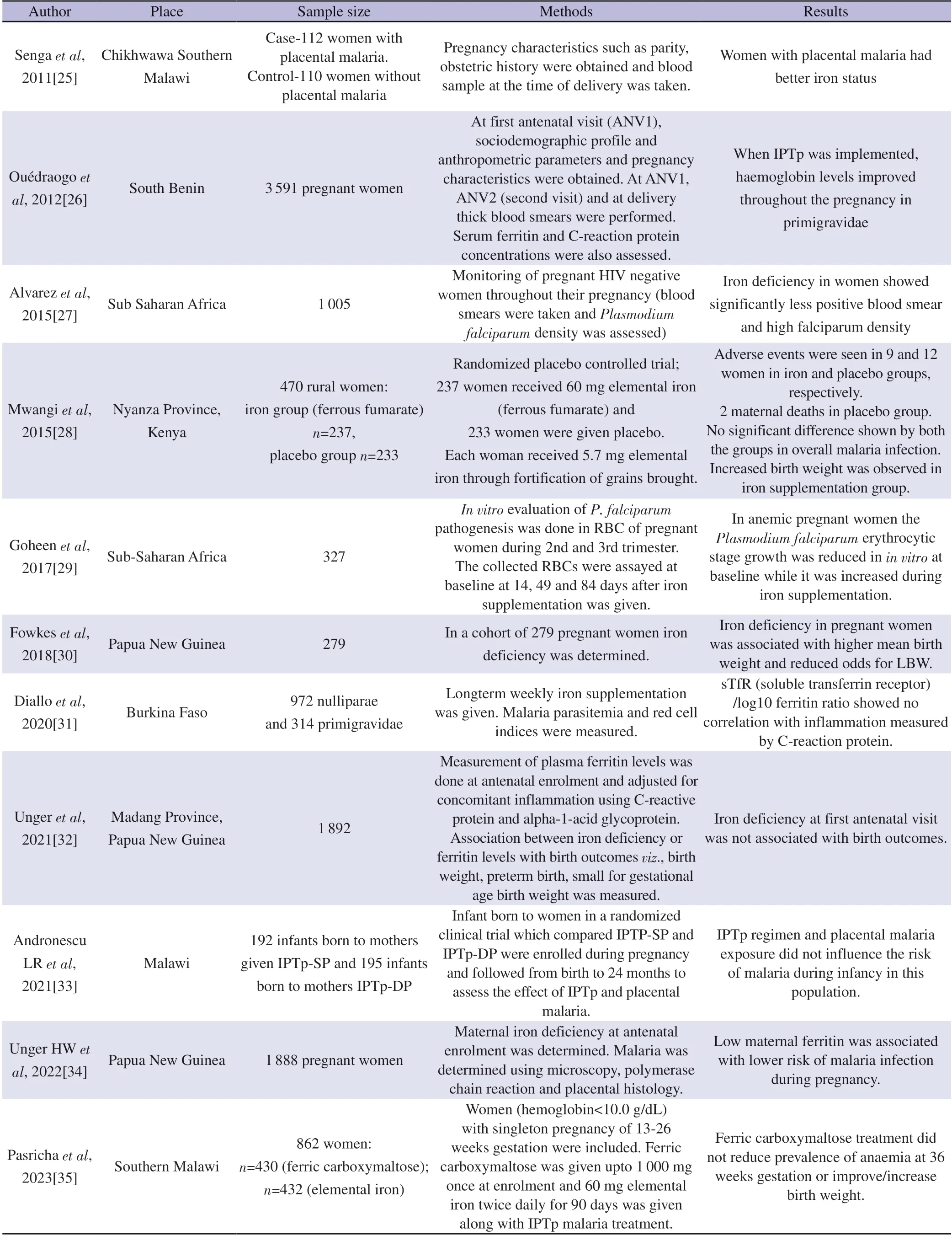

According to Brittenham,malaria morbidity and mortality may increase in the presence of iron deficiency anaemia.The mechanisms that lead to adverse effects with iron supplementation are yet to be established[19].There are findings by different research groups on iron supplementation and malaria risk among pregnant women,but these studies could not resolve whether iron supplementation increases malaria risk in pregnancy.This could be the result of variations in research populations,including factors such as gravidity,baseline iron status,supplementing methods,dosage and timing.A study in Papua Guinea found that when primiparous and multiparous women were given intravenous iron treatment,the frequency of malaria was higher in primiparous women but not in women who are multiparous[11].Besides,a study from Tanzania showed that women who have normal iron stores demonstrated higher prevalence and more severe malaria as compared with women who are deficient in iron,particularly in primiparous women lacking immunity[20].Moreover,maternal iron deficiency is associated with a 5.5-fold decrease in the prevalence of placental malaria[21],suggesting that iron deficiency may protect against malaria infection[22-24].Table 1 illustrated iron status and malaria during pregnancy.

Table 1.Iron status and malaria in pregnancy.

4.Iron and malaria during childhood

The deficiency of iron has detrimental effects on child growth and development[36],and malarial infection negatively affects the iron status of children[37].However,several studies have shown that iron supplementation in malaria-endemic areas raises the risk of malaria in children[21,38,39].In addition,high hepcidin concentration during malaria infection leads to poor distribution and absorption of iron,making iron supplementation ineffective.One of the WHO’s Global Targets for Nutrition 2025 addresses anaemia in children in developing countries[22].The availability of sufficient iron is important for the proper development of immune and hematologic systems and brain in children;therefore,the WHO recommends iron supplementation and malaria treatment for children with anaemia and malaria[40].However,in malaria-endemic regions,the WHO has revised the iron supplementation recommendation for children from universal supplementation to targeted supplementation for only those children who are iron deficient.This change was evidenced by the findings from the Pemba,Zanzibar trial where iron and folic acid supplementation was given to children in the age of 1 to 35 months of age,which resulted in an increased risk of hospitalization and mortality compared to the placebo group[41].This shows that malaria control should be the priority in high malaria-endemic areas.

4.1.Importance of malaria surveillance and treatment

A Cochrane review by Ojukwu et al.on iron supplementation among children in malaria-endemic regions concluded that supplementation with iron did not increase malaria risk or mortality in areas with regular malaria surveillance and treatment.Therefore,iron supplementation should not be held back in malaria endemic regions;instead,emphasis should be given to regular malaria surveillance,prevention and treatment[41,42].Moreover,a recent review by Ojukwu et al.highlighted the revised WHO guidelines that universal supplementation is not recommended for children aged<2 years in malaria-endemic areas.Children should be screened for iron deficiency before receiving supplementation[43].Similarly,some studies suggest that iron supplementation should be delayed until malaria control is ensured,while some studies recommend malaria prophylaxis or treatment when iron supplementation is given.Malaria treatment and control would reduce anaemia,consequently leading to increased iron absorption and improved effectiveness of iron supplementation[43].Iron supplementation may not have adverse effects when regular malaria surveillance and treatment is done,but it can be risky if iron supplementation is given without these measures[2].Many studies have showed that iron supplementation increases the risk of malaria infection.

4.2.Pros and cons of iron supplementation

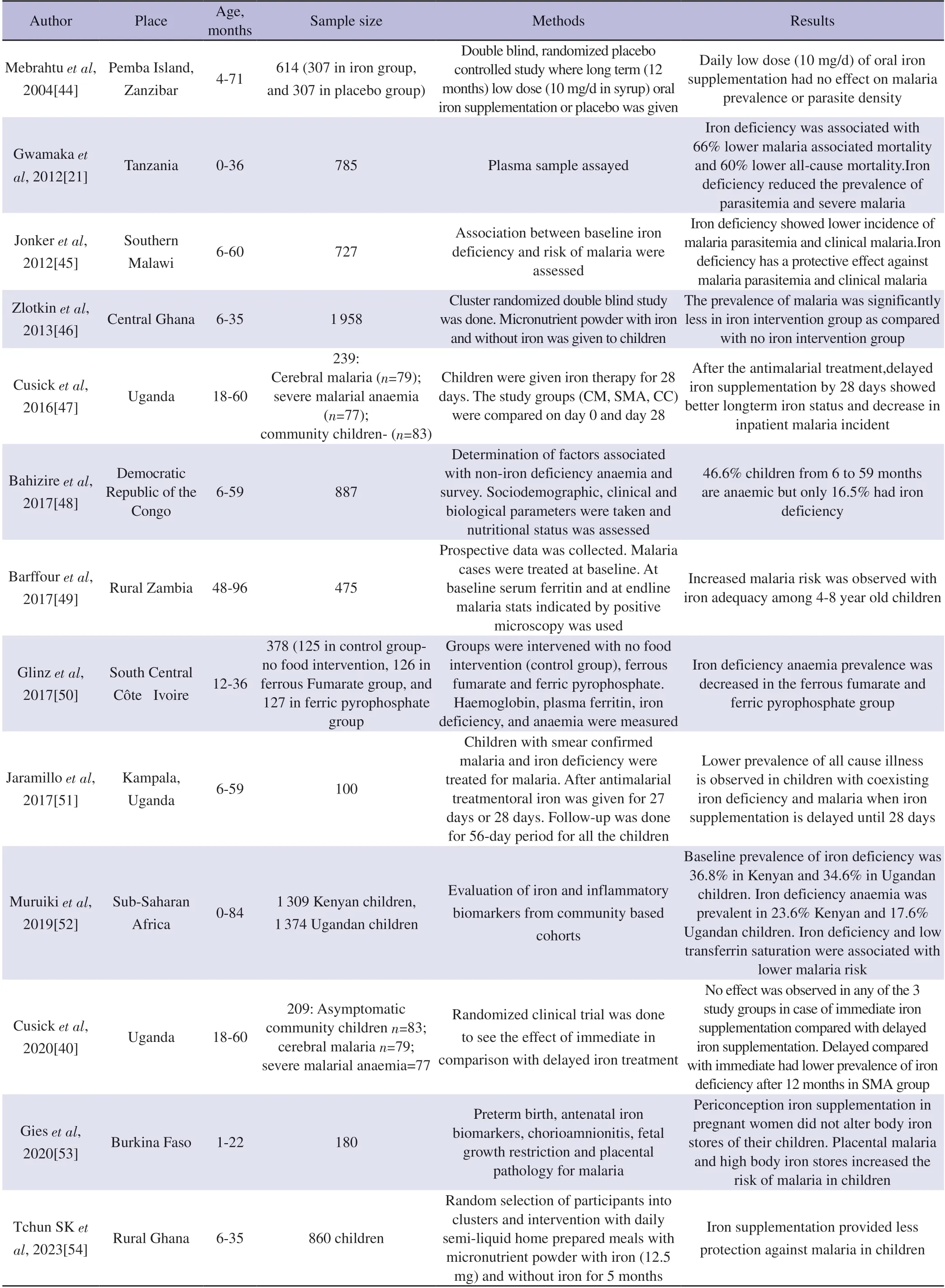

Studies have shown that iron supplementation during malaria infection can aggravate the disease and may even cause death[38].However,a study done by Cusick et al.has demonstrated that supplementing iron 28 days after antimalarial treatment in Ugandan children with iron deficiency and severe malarial anaemia resulted in better iron status in the long term,this effect could be due to a lower concentration of hepcidin after malaria treatment.Also,the inpatient malaria incident decreased in these children[40].Also in a study by Gara et al.,in Nigeria among children 6-60 months of age found that iron plus folate supplementation improved the hematocrit levels compared to folate alone supplementation,and no harm was observed when iron supplementation was given along with folate and antimalarial treatment in acute malaria.This could be due to the inclusion of antimalarial agents and iron and folate supplementation[37].Another study conducted in a birth cohort(n=785,from birth up to 36 months of age) in Tanzanian children reported that iron deficiency provides protection to children from malaria infection,morbidity and mortality.However,a randomized,placebo-controlled trial done in Pemba,Zanzibar,wherein children were given iron and folic acid supplementation showed a 15%increase in all-cause mortality,raising concern over routine supplementation with iron in regions where malaria is prevalent[21].When long-term (12 months) low-dose (10 mg/d in syrup) oral iron supplementation was given to preschool children of Pemba Zanzibar in 2004,it was observed that it did not increase malaria infection.Table 2 briefly describes about iron status and malaria in children.

Table 2.Iron status and malaria in children.

5.Recommendations

a.The WHO recommends that supplementation with iron and folic acid in malaria should be given only with malaria treatment.

b.In malaria endemic areas iron supplementation to infants and children should be given in combination with public health measure to diagnose,prevent and treat malaria infection[55].

c.In malaria-endemic regions,supplementation with iron and folic acid should be given only to anaemic group and blanket supplementation of iron and folic acid should be avoided.

d.Regular malaria surveillance and treatment services should be provided.

e.Care should be taken while providing diet and/or dietary supplement during malaria infection.

f.No nutritional supplement should be given during malaria infection unless necessary.

g.Improving malaria awareness to seek timely healthcare to prevent and treat malaria is crucial in malaria endemic areas[56].

h.Aiming iron supplementation programmes at the end of wet season could reduce the potential risks of malaria[57].

6.Conclusions

This is a perspective type narrative review article;therefore,this article provides only a broad perspective on this topic.The incomplete understanding of the risks and advantages of iron supplementation in malaria-endemic regions is a major challenge for the scientific community.Supplementation with iron for anaemia treatment in malaria-affected individuals increases the severity of the disease.Malaria parasites require iron for their growth,therefore,iron supplementation can exacerbate the severity of malaria.Although iron deficiency anaemia and malaria are amongst the major global public health problems,the coverage of iron and folic acid supplementation and intermittent preventive treatment of malaria is limited in many countries.In contrast,the prevalence and exposure to malaria in pregnancy is high.It has been observed that supplementation with iron along with malaria chemoprophylaxis reduces the risk of preterm birth,low birth weight and stillbirth and decreases malnutrition.In pregnancy,malaria infection through placental malaria leads to maternal anaemia,preterm birth,low birth weight,small for gestational age,miscarriage,or stillbirth.Pregnant women should be advised against travelling to malaria-endemic areas.If they must travel,proper region-specific chemoprophylaxis must be given to prevent malaria infection.The WHO recommends administering iron supplementation with malaria prophylaxis and treatment in high malaria transmission areas.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to ICMR National Institute of Malaria Research ICMR-NIMR) for infrastructural support.Neha Surela is the recipient of junior research fellowship from the University Grants Commission (UGC) Govt.of India.Amrendra Chaudhary is the recipient of junior research fellowship from the Dept of Biotechnology (DBT),Govt.of India.Poonam Kataria is the recipient of junior research fellowship from the University Grants Commission (UGC) Govt.of India.We also thank all lab members for their generous support during this work.

Funding

The authors received no funding for the study.

Authors’ contributions

NS and JD designed the original idea and developed it in detail,reviewed the literature and wrote the manuscript.NS generated all the tables and arranged references.AC and PK helped review the literature,provided valuable feedback,and helped revise the manuscript.

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine2024年1期

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine2024年1期

- Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine的其它文章

- Unveiling health rights: A call to action for sex workers' HIV care in the Philippines

- Fatal cases in pediatric patients after post-exposure prophylaxis for rabies: A report of two cases

- Clinical profile and risk factors of Strongyloides stercoralis infection

- Occurrence of K1 and K2 serotypes and genotypic characteristics of extended spectrum β-lactamases-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from selected hospitals in Malaysia

- Informing policy makers in developing countries: Practices and limitations of geriatric home medication review in Malaysia-A qualitative inquiry

- Ferritin and mortality in hemodialysis patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis