SsRSS1 mediates salicylic acid tolerance and contributes to virulence in sugarcane smut fungus

ZHANG Hao-yang,YANG Yan-fang,GUO Feng,SHEN Xiao-rui,LU Shan,,,CHEN Bao-shan,,

1 College of Agriculture/Guangxi Key Laboratory of Sugarcane Biology,Guangxi University,Nanning 530004,P.R.China

2 State Key Laboratory for Conservation and Utilization of Subtropical Agro-Bioresources/College of Life Science and Technology,Guangxi University,Nanning 530004,P.R.China

3 Ministry and Province Co-sponsored Collaborative Innovation Center for Sugarcane and Sugar Industry,Guangxi University,Nanning 530004,P.R.China

Abstract Sugarcane smut caused by Sporisorium scitamineum is a destructive disease responsible for significant losses in sugarcane production worldwide. However,the mechanisms underlying the pathogenicity of this fungus remain largely unknown. In this study,we found that the disruption of the SsRSS1 gene,which encodes a salicylic acid (SA) sensing regulator,does not affect phenotypic traits such as the morphology,growth rate,and sexual mating ability of haploid basidiospores,but rather reduces the tolerance of basidiospores to SA stress by blocking the induction of SsSRG1,a gene encoding a SA response protein in S.scitamineum. SsRSS1 deletion resulted in the attenuation of the virulence of the fungus. In addition to a significant reduction in whip formation,a portion of plantlets (18.3%) inoculated with the ΔSsRSS1 strains were found to be infected but failed to produce whips for up to 90 days post-inoculation. However,the development of hyphae and teliospore from the ΔSsRSS1-infected plants that formed whips seemed indistinguishable from that in the wild-type-infected plants. Combined,our findings suggested that SsRss1 is required for maintaining fungal fitness in planta by counteracting SA stress.

Keywords: Sporisorium scitamineum,SsRSS1,pathogenicity,salicylic acid response

1.Introduction

Sugarcane smut,first reported in Natal,South Africa,approximately one and a half centuries ago,is now an important disease in the sugarcane industry worldwide(McMartin 1945;Gaoet al.2021;Rajputet al.2021;Maiaet al.2022). The most prominent symptom of the disease is the development of a black whip composed of teliospores and debris of plant tissues in the apex of the shoot in the late stage of infection (Tanigutiet al.2015). The basidiomyceteSporisoriumscitamineum,the causative agent of sugarcane smut,is a dimorphic,biotrophic fungus that exhibits three distinct cell forms during its life cycle,namely,haploid basidiospores,dikaryotic hyphae,and diploid teliospores (Tanigutiet al.2015). The dikaryotic hyphae formed by the mating of two yeast-like,non-pathogenic basidiospores are capable of invading host plants (Yanet al.2016).

Salicylic acid (SA) is a phenolic phytohormone widely present in higher plants (Lefevereet al.2020;Houet al.2022). Acting as an inducer of abiotic stress tolerance or activator of systemic acquired resistance in plants,SA has been shown to be involved in the regulation of a variety of biological processes,including seed germination,growth,and defense responses to biotrophic pathogens by regulating a complex network of signaling pathways (Saleemet al.2021). The SA-mediated signal transduction network activates defense responses in the host plant in response to an invading pathogen,ultimately inducing cell death at the site of infection to prevent further invasion (An and Mou 2011). However,some pathogens have evolved mechanisms that limit SA biosynthesis that involve the elimination of its precursor,a strategy that allows them to counteract host defenses and successfully colonize the plant (Doehlemannet al.2008).

Rss1 proteins belong to the binuclear zinc cluster of transcription factors found only in fungi and are characterized by the presence of a highly conserved DNAbinding domain (CysX2CysX6CysX5-9CysX2CysX6-8Cys)(Rabeet al.2016). These proteins regulate a variety of cellular processes,including meiosis,nitrogen utilization,sexual development,and the cell cycle (Pan and Coleman 1990;Andersonet al.1995;Toddet al.1997;Goldaret al.2005). In the maize smut pathogen,Ustilagomaydis,theRSS1gene was reported to be activated by both SA and anthranilic acid to regulate the expression of genes related to SA and tryptophan degradation during biotrophic growth (Rabeet al.2016). AlthoughRSS1was found to be significantly upregulated during the infection of maize,its deletion did not affect the virulence of the pathogen (Rabeet al.2016). In contrast toU.maydis,little is known about SA-responsive genes inS.scitamineum. In this study,we characterized the homolog of Rss1 inS.scitamineum,SsRss1,and found that in addition to similarities to Rss1 ofU.maydis,SsRss1 was also required for maintaining the fitness of the fungus during plant colonization. Our findings advance our understanding of the mechanism underlying the pathogenicity of this important phytopathogenic fungus.

2.Materials and methods

2.1.Fungal and bacterial strains and culture conditions

Wild-type haploid basidiospores of opposite mating types,JG36 (MAT-1) and JG35 (MAT-2),of the sugarcane smut fungusS.scitamineumwere grown in liquid YEPS(1% yeast extract,2% sucrose,and 2% peptone) on a rotary shaker at 200 r min-1or in solid YEPS plates at 28°C for 2 days (Brachmannet al.2001;Luet al.2017).Escherichiacolistrain DH5α was grown on Luria agar(LA) plates or Luria broth (LB) supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics at 37°C. For fungal transformation,Agrobacteriumtumefaciensstrain Agl1 was grown at 28°C on LA plates or in liquid LB with shaking at 200 r min-1.

2.2.Construction of SsRss1 deletion mutants and complementation strains

The sequences of all the primers used in this study are listed in Table 1.SsRSS1gene deletion was performed using the previously described CRISPR/Cas9/T-DNA system forS.scitamineum(Luet al.2017). The target sequence (5′-ggcaagctggagccggcag-3′) ofSsRSS1was introduced into the sgRNA expression cassette by overlapping PCR using pSgRNA-SsU6 as the template and four primers (U-F,gR-R,gRT rss1+,and U6T rss1-). The PCR product served as a template for amplifying the sgRNA expression cassette using the primer pair U-Fs-BamHI/gR-R-HindIII. The sgRNA expression cassette was cloned into pLS-HCas9 between theBamHI andHindIII restriction sites to generate the disruption construct pLS-rss1,which was then transformed intoA.tumefaciensstrain Agl1 by electroporation (Mainet al.1995). A colony carrying pLSrss1 was used for the transformation of JG35 and JG36 basidiospores to generate strains JG35-ΔSsRSS1and JG36-ΔSsRSS1,as previously described (Sunet al.2014).

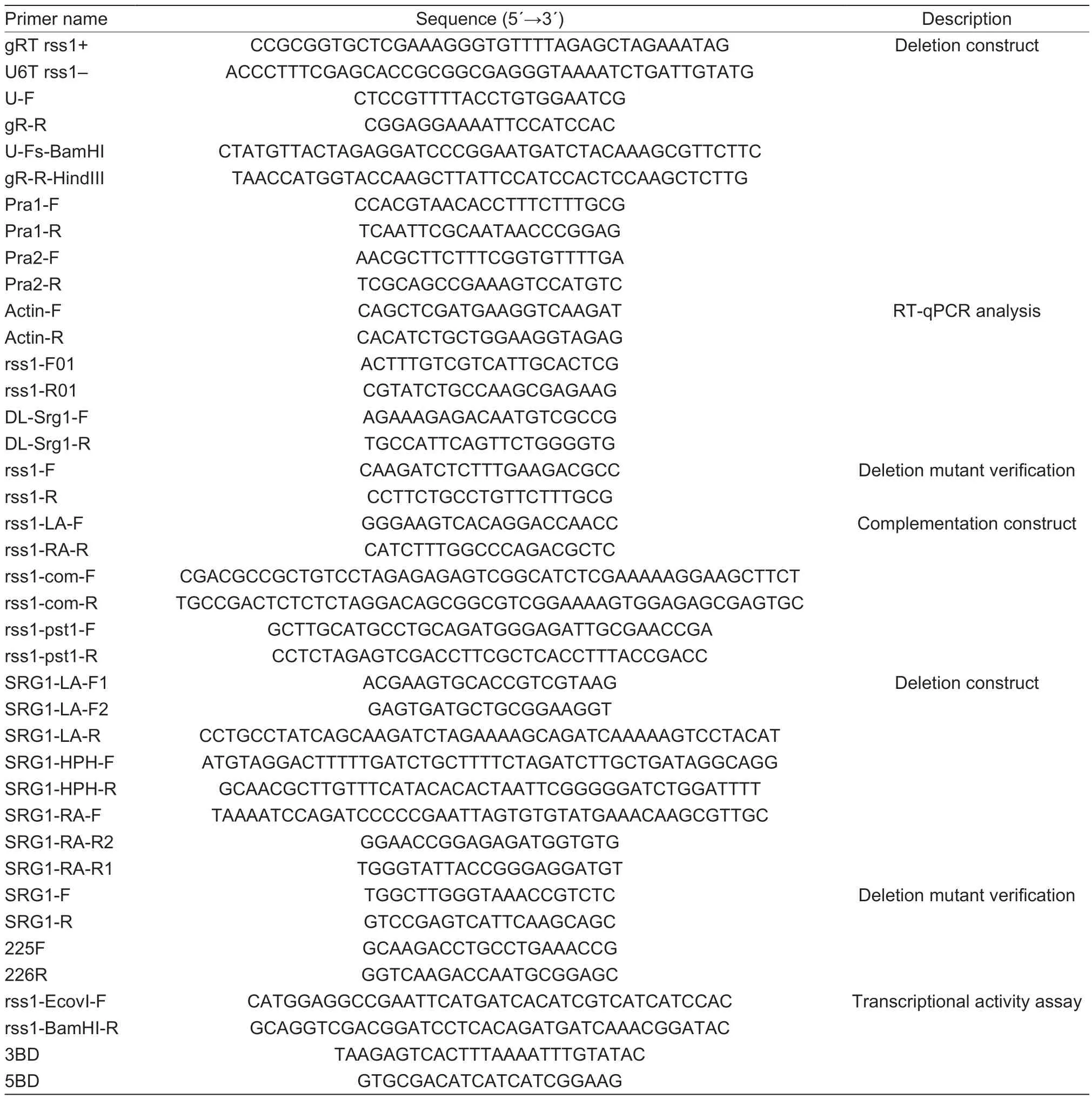

Table 1 Primers used in this study

For the complementation ofSsRSS1mutant strains,the target sequence in theSsRSS1sequence was modified by base substitution that did not change the amino acid sequence,as previously described (Luet al.2017). A fragment containing the promoter and the open reading frame with a modified sequence was PCR amplified from JG35 genomic DNA and cloned into pLSNcom at thePstI restriction site. The resulting plasmid pRss1-C was transformed intoA.tumefaciensstrain Agl1 by electroporation. A colony carrying pRss1-C was used for the transformation of theSsRSS1mutant to yield strains C-JG35-ΔSsRSS1and C-JG36-ΔSsRSS1.

2.3.Construction of SsSRG1 deletion mutants

The primers used for generating ΔSsSRG1were listed in Table 1. The gene deletion follows the strategy described(Sunet al.2019). The two fragments flaking theSsSRG1gene were amplified using wild-typeS.scitamineumgenomic DNA as template and fused with half partial-overlapping hygromycin B resistance gene sequence which were amplified using plasmid pEX2 as template (Yanet al.2016).

2.4.Transcriptional activity assay

Plasmid pGBKT carries a reporter (Mel-1,encoding α-galactosidase) that is capable of hydrolyzing the substrate X-α-Gal to produce blue products,once it is transcriptionally activated by a transcription factor.The CDS sequence ofSsRSS1was amplified by PCR with the primer pair rss1-EcoVI-F/rss1-BamHI-R usingS.scitamineumJG36 cDNA as template. The PCR products were cloned into theEcoRI andBamHI restriction sites of pGBKT vector using an ClonExpress II One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme,Nanning,China) to generate the construct pGBKT-SsRSS1. After amplification and clone selection inE.coli,the pGBKTSsRSS1was transformed into yeast strain Y2HGold using Yeastmaker Yeast Transformation System 2(Clontech,Beijing,China) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Yeast strains carrying pGBKT-SsRSS1were spotted onto the solid tryptophan-deficient medium (SDO)supplemented with the X-α-Gal (a final concentration of 40 mg mL-1) and incubated at 30°C for 3 days for colorization.

2.5.Phenotypic characterization and stress tolerance assays

For the growth assay,haploid sporidia of wild-type and mutant strains were cultured overnight and then diluted to an OD600of 0.1 with fresh liquid YEPS medium. An aliquot was cultured for another 48 h at 28°C with shaking at 200 r min-1. The OD600was measured with a UV-Vis Spectrophotometer Model TU-1950 (Persee Ltd.,Beijing,China) every 4 h to monitor the budding of haploid sporidia (Sunet al.2019).

For the stress tolerance assay,serial dilutions(1×107to 1×103mL-1) ofS.scitamineumsporidia were inoculated on solid YEPS plates supplemented with NaCl(500 mmol L-1),H2O2(1 mmol L-1),Congo Red (0.5 mmol L-1),SDS (0.1 mmol L-1),or SA (5 mmol L-1) (Denget al.2018).

For the mating assay,wild-type or mutant haploid sporidia were grown in liquid YEPS medium to an OD600of 1.0. Compatible haploid sporidia were mixed in a 1:1 ratio,co-spotted on solid medium,and incubated in the dark at 28°C for 2-3 days before imaging (Zhuet al.2019).

2.6.Virulence assay and microscopy

Sugarcane inoculations were performed by soaking the roots of sugarcane tissue culture seedlings in cell suspensions (1×107cells resuspended in H2O) for 3 days.The tissue culture seedlings were then planted in nursery substrate as previously described (Luet al.2021a).

Colonies ofS.scitamineumwere photographed using a Nikon SMZ25 stereomicroscope equipped with a DS-Fi2 camera. Sugarcane tissue preparation and staining were performed as described in (Luet al.2021a). Fungal cells were visualized using Olympus BX53 and Olympus CX33 Microscopes (Olympus Corporation,Tokyo,Japan).

2.7.RNA isolation and RT-qPCR

Basidiospores of wild-type and ΔSsRSS1mutant strains grown on YEPS plates with or without 5 mmol L-1SA were ground to a powder in liquid nitrogen and total RNA was extracted using an RNA Extraction Kit (TaKaRa,Beijing;No.9769) following the manufacturer’s protocol.A PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (TaKaRa;RR047A) was used for cDNA synthesis. qPCR analysis of target genes was performed on a LightCycler 480 II using TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa;RR820A). The experiment was done in three biological and three technical replicates. Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCtmethod,with theS.scitamineumactin gene serving as an endogenous control.t-tests were used to assess statistically relevant differences between expression levels in the different strains. AP-value <0.05 was considered significant.

2.8.Teliospore isolation and germination

Whips were excised from plantlets inoculated with mixtures of compatible wild-type strains or ΔSsRSS1mutants. The teliospores were collected and suspended in sterile water to a cell density of 1×103mL-1. Teliospore suspensions were spread on YEPS plates and incubated at 28°C until germination. After 3 days,the percentage of germination was compared between wild-type and ΔSsRSS1mutant strains.

3.Results

3.1.ldentification of the S.scitamineum RSS1 gene

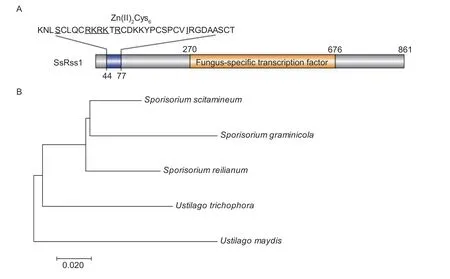

The putativeSsRSS1gene encoding SsRss1,a homolog of the Rss1 protein ofU.maydis(UMAG_05261),was identified by BLASTn search against theS.scitamineumnucleotide sequence database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assembly/GCA_900002365.1,2022-05-04)usingU.maydisRss1 as a query by Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi,2022-05-04). SsRss1 shares 73.46%sequence similarity to UmRss1. TheSsRSS1gene is 2 586 bp long with no detectable introns and encodes a protein of 861 amino acids. The amino acid sequence of SsRss1 contains a characteristic GAL4-like Zn(II)2Cys6DNA-binding domain (aa 47-77) that forms a binuclear zinc ion cluster. In addition,SsRss1 was predicted to contain a putative fungal-specific transcription factor domain spanning aa 301-461 (Fig.1-A). We further showed that SsRss1 had transcriptional activity in the GAL4 transcriptional activation assay(Appendix A). Phylogenetic analysis revealed that Rss1s of basidiomycetous fungi formed a unique clade differentiating from those of the genusSporisoriumandUstilago(Fig.1-B).

3.2.SsRSS1 is not required for budding and sexual mating

Fig. 1 Phylogenetic analysis of the SsRss1 protein. A,domain arrangement of the SsRss1 protein. The underlined letters indicate DNA-binding sites and the cysteine indicates zinc ion-binding sites. B,phylogenetic tree analysis of SsRss1. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method. The optimal tree with the sum of branch length=0.36092104 is shown. The tree is drawn to scale,with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Poisson correction method and are in the units of the number of amino acid substitutions per site. The analysis involved 5 amino acid sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There was a total of 681 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7. The accession numbers: SJX62697.1,Sporisorium reilianum;XP_011392291.1,Ustilago maydis;XP_029738294.1,Sporisorium graminicola;SPO26878.1,Ustilago trichophora.

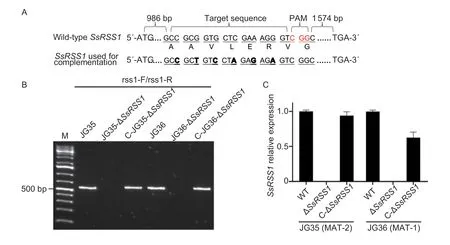

Fig. 2 Verification of the disruption and complementation of the SsRSS1 gene. A,nucleotide and amino acid sequences of wild-type and base-modified SsRSS1 targets. B,PCR-based verification of the disruption and complementation of the SsRSS1 gene. The primer pair rss1-F/rss1-R was used to amplify a 500-bp fragment of the SsRSS1 gene. C,quantification of the SsRSS1 transcript levels in ΔSsRSS1 and complemented strains (C-ΔSsRSS1). Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method with the Sporisorium scitamineum actin gene serving as an endogenous control. Data are mean±SD. The experiment was done in three biological and three technical replicates.

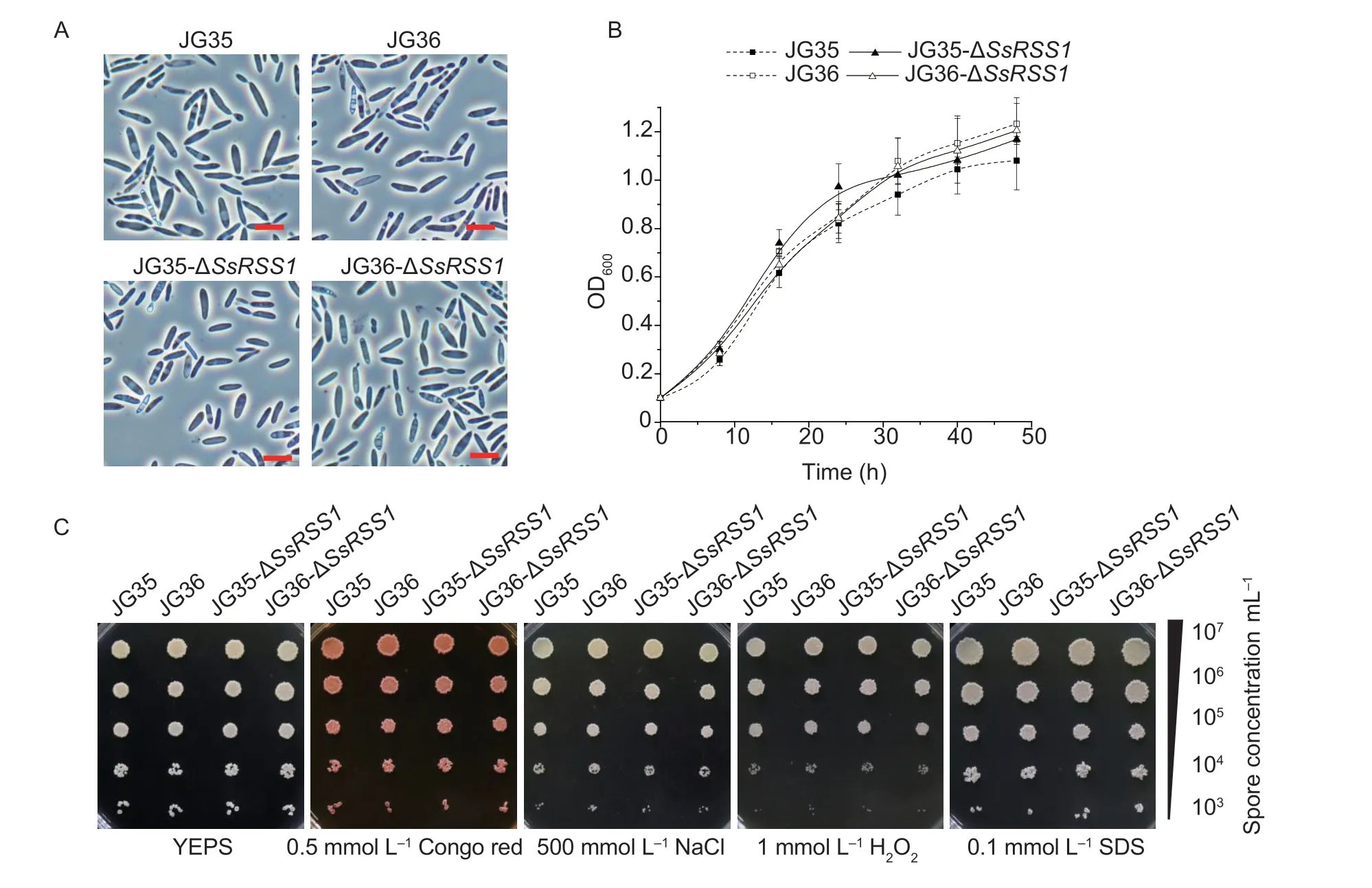

Fig. 3 Characterization of Sporisorium scitamineum SsRSS1 deletion strains. A,microscopic observation and imaging of basidiospores of wild-type strains and ΔSsRSS1 mutants. Scale bar=10 μm. B,the saprophytic growth curve of wild-type strains and ΔSsRSS1 mutants. The strains were cultured in liquid YEPS for 48 h. Data are mean±SD. The experiment was performed in three biological and three technical replicates. C,SsRSS1 is dispensable for stress tolerance. Serially diluted basidiospores of wild-type strains and ΔSsRSS1 mutants were spotted onto solid YEPS medium supplemented with Congo red (0.5 mmol L-1),NaCl (500 mmol L-1),H2O2 (1 mmol L-1),or SDS (0.1 mmol L-1) and incubated at 28°C for 72 h.

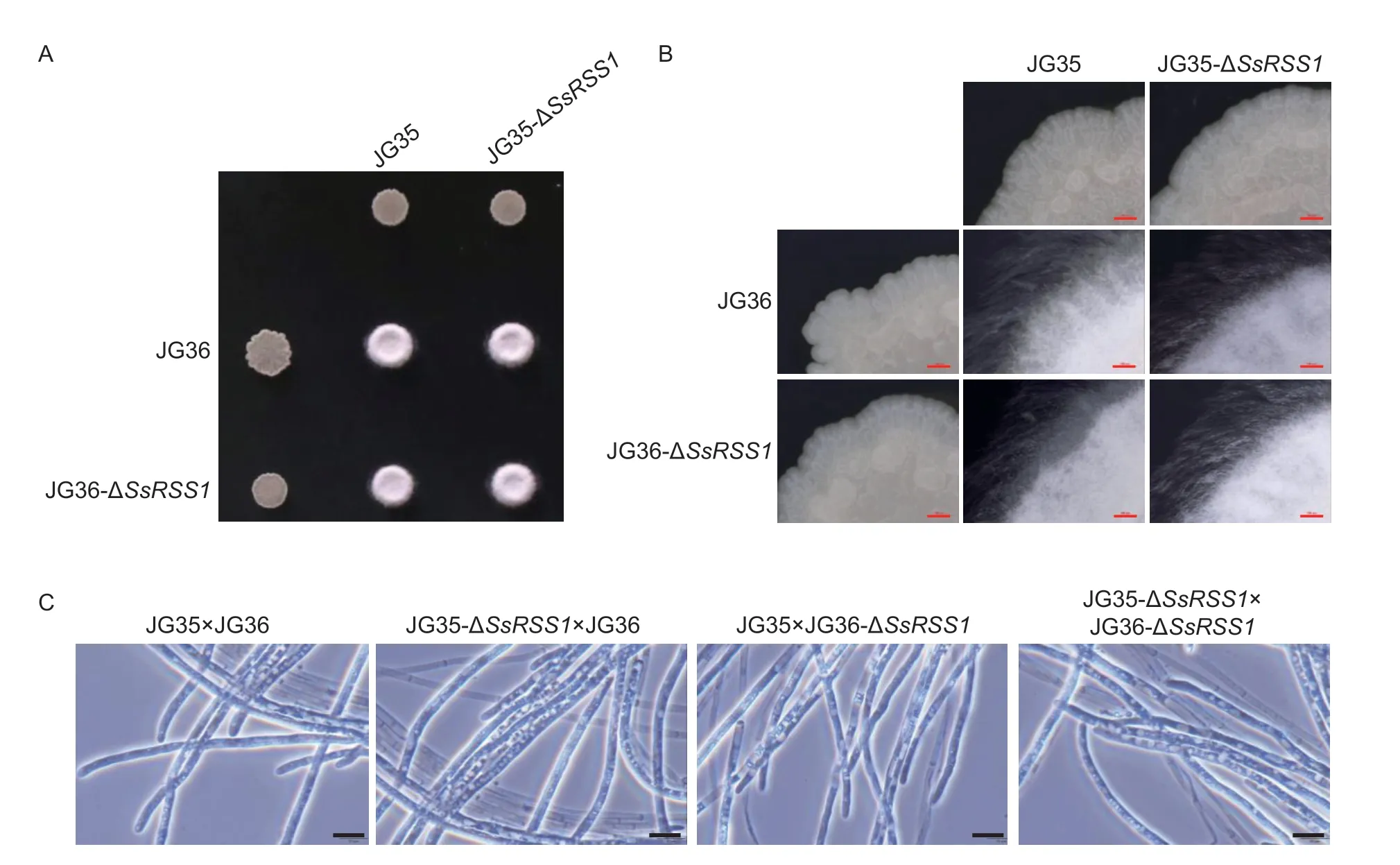

Fig. 4 Mating behavior of SsRSS1 deletion mutants. A,mating assay with the sporidia of wild-type strains and SsRSS1 deletion mutants on a YEPS plate. B,colonies of SsRSS1 deletion mutants after mating. Scale bar=500 μm. C,dikaryon hyphae of SsRSS1 deletion mutants after mating. Scale bar=10 μm.

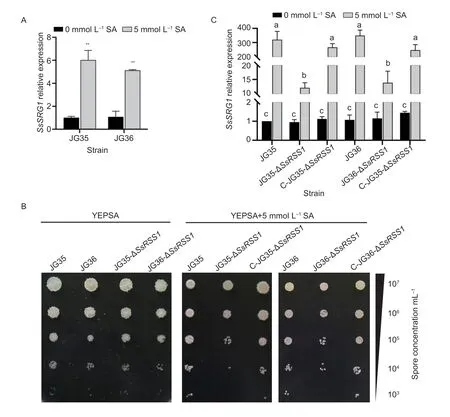

Fig. 5 SsRSS1 is involved in tolerance to salicylic acid. A,quantification of the SsRSS1 transcript levels in the wild-type strains cultured on YEPS plates and YEPS medium supplemented with 5 mmol L-1 SA. B,serially diluted basidiospores of wild-type strains and ΔSsRSS1 mutants were spotted onto solid YEPS medium supplemented with 5 mmol L-1 SA and incubated at 28°C for 72 h. C,quantification of the SsSRG1 transcript levels in the SsRSS1 deletion and complemented strains cultured on YEPS plates or under 5 mmol L-1 SA-induced stress. Data are mean±SD. The experiment was done in three biological and three technical replicates. P-values were calculated based on a Student’s t-test of replicate 2-ΔΔCt values for SsRSS1 in the wild-type strain which cultured in YEPS plates and YEPS medium supplemented with 5 mmol L-1 SA. **,P<0.01. Different lowercase letters above columns indicate statistical differences at P<0.05.

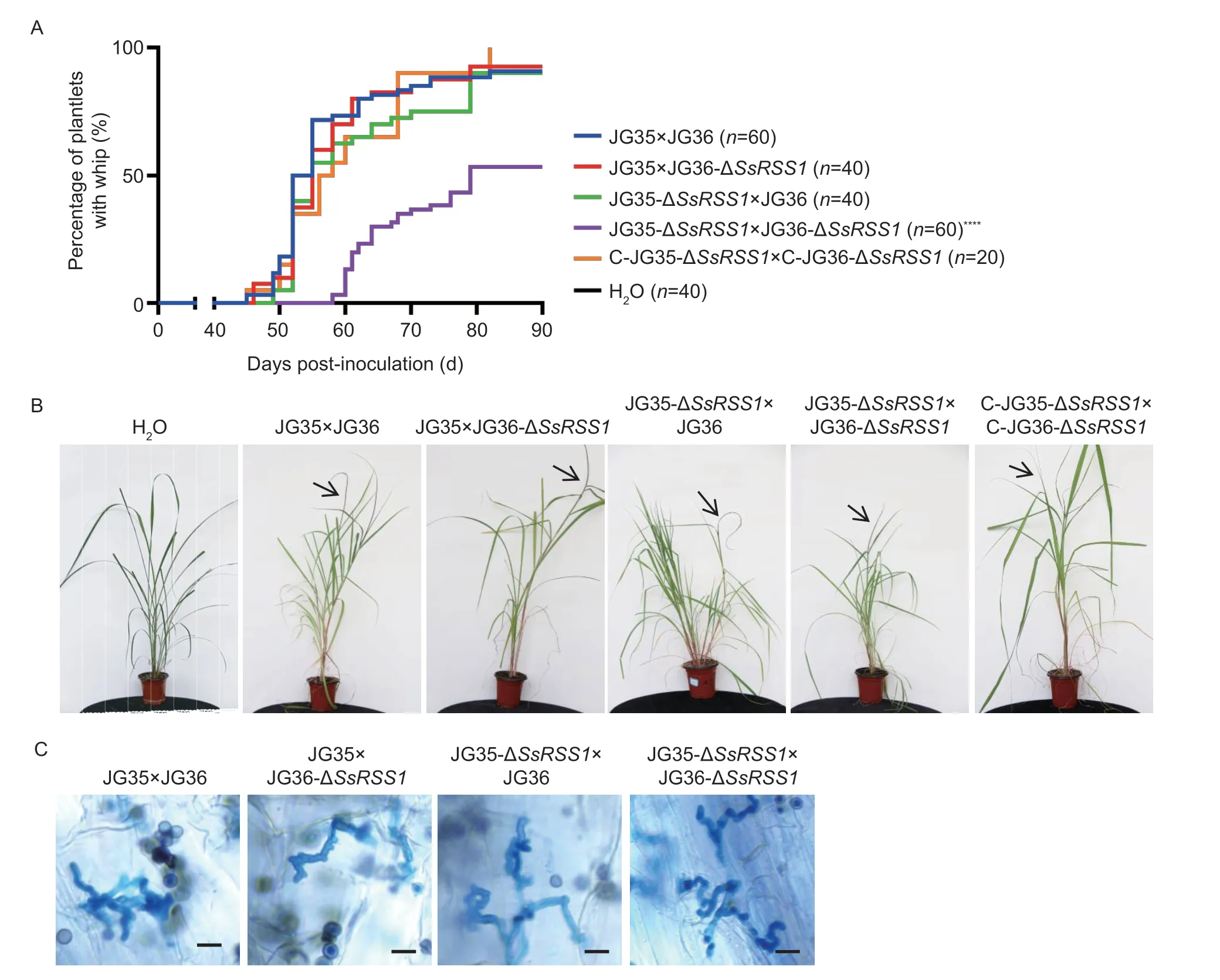

Fig. 6 SsRSS1 is essential for Sporisorium scitamineum pathogenicity. A,the progression of whip development in SsRSS1 deletion mutants and complemented strains. Tissue culture-derived plantlets of the smut-susceptible sugarcane variety ROC22 were inoculated with combinations of wild-type strains (JG35×JG36),ΔSsRSS1 mutants,and/or complemented strains (C-ΔSsRSS1)at an OD600 of 1.0. Significance was set at P=0.05. ****,P<0.0001. B,no differences were observed between infected plantlets inoculated with wild-type strains and those inoculated with the ΔSsRSS1 strains. Arrows indicate whips. C,histopathological analysis of dikaryotic hyphae and in vivo. Scale bar=10 μm.

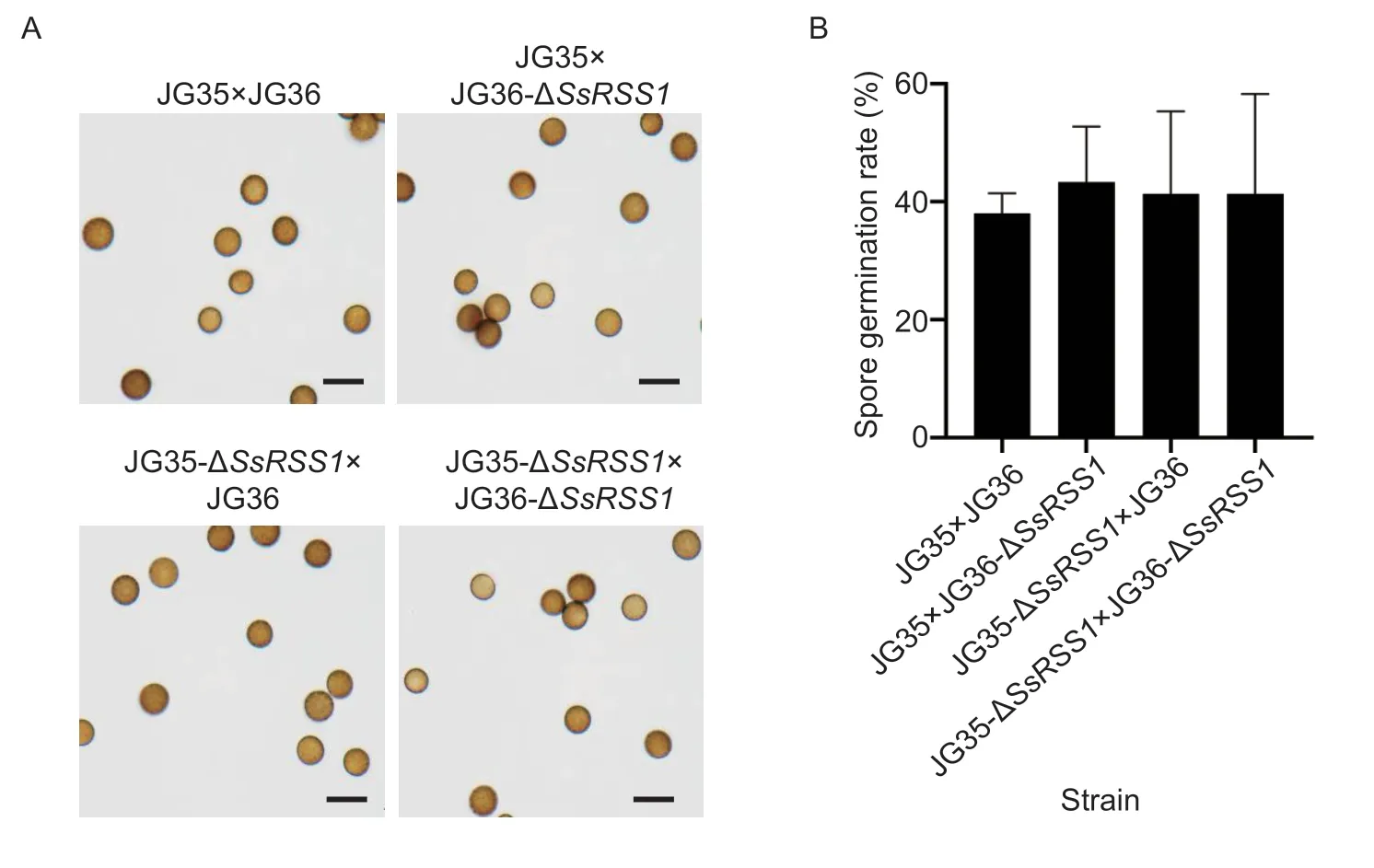

Fig. 7 SsRSS1 is dispensable for teliospore formation and germination. A,microscopic imaging of teliospores from wild-type(JG35×JG36) and SsRSS1 deletion mutants. B,the germination rate of teliospores of SsRSS1 deletion mutants. Teliospores were collected and suspended in sterile water to a cell density of 1×103 mL-1. Teliospore suspensions were spread onto YEPS plates and incubated at 28°C until germination. Bar=10 μm.

To explore the role of SsRss1 inS.scitamineum,the CRISPR-Cas9/T-DNA system was used to generateSsRSS1deletion mutants and the corresponding complementation strains (Fig.2-A and B). RT-qPCR analysis confirmed thatSsRSS1was not expressed in the disruptants and thatSsRSS1expression was restored fully (C-JG35-ΔSsRSS1) or up to 60% (C-JG36-ΔSsRSS1) in the complementation strains (Fig.2-C).

No obvious difference in cell morphology,growth rate,tolerance to cell wall stress,hyperosmotic stress,or oxidative stress was detected between the haploid basidiospores of the wild-type strains and theSsRSS1-null mutant during sporidial growth (Fig.3),indicating thatSsRSS1is not required for basidial budding and is not involved in responses to hyperosmotic or oxidative stress or the maintenance of cell wall integrity.

Mating assays showed that the disruption ofSsRSS1did not affect the mating behavior of the fungal strains as the co-spotting of JG35-ΔSsRSS1×JG36,JG35×JG36-ΔSsRSS1,or JG35-ΔSsRSS1×JG36-ΔSsRSS1combinations all resulted in filamentous growth and fluffy white colonies with normal dikaryotic hyphae (Fig.4).

3.3.Deletion of SsRSS1 increases the sensitivity of S.scitamineum to SA stress

To investigate whetherS.scitamineumSsRSS1gene is induced by SA,total RNA was isolated from the wildtype haploid basidiospores grown onto YEPS medium supplemented with 5 mmol L-1SA and used for cDNA synthesis. RT-qPCR quantification showed that the expression of theSsRSS1gene was upregulated in the presence of salicylic acid by 5 and 6 folds for the wild-type JG35 and JG36,respectively (Fig.5-A).

To evaluate the tolerance of theSsRSS1-null mutants to SA stressinvitro,serial dilutions of wild-type cells andSsRSS1-null haploid mutant cells were spotted onto YEPS medium supplemented with SA at varied concentration.Since the wild-type strains failed to grow at medium supplemented with 10 mmol L-1SA and the mutants at 8 mmol L-1SA with inoculum of OD600=1.0 (Appendix B),the final assay medium was set at 5 mmol L-1SA. As shown in Fig.5-B,mutants of both mating types exhibited marked growth inhibition compared with the wild-type or their complemented strains that reached at least an order of magnitude,demonstrating thatSsRSS1is required for resistance to SA inS.scitamineum.

We further measured the expression level ofSsSRG1,a gene inS.scitamineumthat is homologous to the SAresponsive geneSRG1ofU.maydis(UMAG_05967;Rabeet al.2016) with 90.6% sequence similarity between their corresponding proteins.SsSRG1expression were upregulated by more 300 folds in the wild type when exposed to medium supplemented with 5 mmol L-1SA,as compared with on regular YEPSA medium,but only 22.8 folds (JG35 background) and 29.9 folds (JG36 background) in ΔSsRSS1mutants;reintroduction of aSsRSS1into the mutant fully restored the induction level ofSsSRG1(Fig.5-C). These results suggest thatSsRSS1is required to mediate the full upregulation ofSsSRG1in response to the SA stress.

To investigate whetherSsSRG1play a role in SA tolerance,SsSRG1deletion mutants were generated in both mating type strains (Appendix C). Deletion ofSsSRG1did not seem to affect the cell morphology and sexual mating (Appendix D) or impair the tolerance of theSsSRG1deletion mutants to SA stressinvitro(Appendix E),indicating thatSsSRG1does not contribute to the SA tolerance inS.scitamineum.

3.4.Deletion of SsRSS1 attenuates the virulence of S.scitamineum

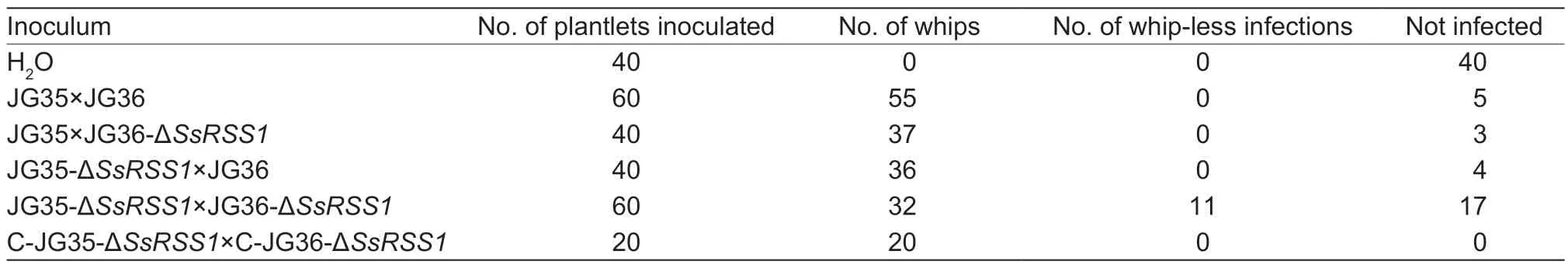

To assess the role ofSsRSS1in the pathogenicity ofS.scitamineum,virulence assays of ΔSsRSS1mutants were performed in tissue culture-derived plantlets of the smut-susceptible sugarcane variety ROC22. The first sign of whip appeared at 45 days post-inoculation (dpi),with a final incidence of 91.7% at 90 dpi being recorded with the wild-type strains (JG35×JG36). Similar rates(90-100%) were recorded with the deletion of one allele ofSsRSS1(JG35-ΔSsRSS1×JG36 or JG35×JG36-ΔSsRSS1) and the complemented strains (C-JG35-ΔSsRSS1×C-JG36-ΔSsRSS1). However,the first sign of whip appeared at 58 dpi and the final whip percentage was 53.3% at 90 dpi for mutants with bothSsRSS1alleles deleted (JG35-ΔSsRSS1×JG36-ΔSsRSS1) in dikaryotic cells,significantly lower than that of the wild types (Fig.6;Table 2).

Table 2 Detection of the pathogenicity of SsRSS1 deletion and complemented strains1)

To investigate whether the asymptomatic plantlets had been infected,the stem apical meristem of the whip-less plantlets was examined for the presence of fungal hyphae.Histopathological examination revealed that 11 out of 28 whip-less plantlets inoculated with JG35-ΔSsRSS1×JG36-ΔSsRSS1were hyphae-positive,whereas the rest that had been inoculated with other combinations of fungal strains or the control were all hyphae-negative (Table 2).Sporisoriumscitamineum-specific PCR confirmed that the whip-less but hyphae-positive plantlets were indeed infected with JG35-ΔSsRSS1×JG36-ΔSsRSS1(data not shown). No obvious differences in the morphology of the hyphae and teliospores or the germination of teliospores between ΔSsRSS1mutants and the wild-type strains were observed (Fig.7),suggesting that SsRss1 is not required for teliospore development and germination.

4.Discussion

To date,most of the genes found to regulate pathogenicity inS.scitamineumare also essential for regulation of mating,e.g.,SsKPP2,SsGPA3,SsUAC1andSsADR1,components of MAPK and cAMP/PKA signal transduction pathways (Denget al.2018;Changet al.2019),and those encoding ligands and receptors of the pheromone system or its regulators (Luet al.2017;Sunet al.2019;Zhuet al.2019),andSsPEP1,SsATG8,SsAGC1(Wanget al.2019;Zhanget al.2019;Luet al.2021b). SsPEP1 functions to counteract the oxidative stress from the host plant to guard the fungus in the sugarcane plant (Luet al.2021b),a mechanism similar to the PEP1 for the maize smut fungusU.maydis(Hemetsbergeret al.2012). By genetic dissection of filamentous mutants,Luetal.(2021a)

showed that filamentous growth and virulence could be uncoupled inS.scitamineum,implying that sexual mating and pathogenicity were two different events,though cross-talk may exist. In this study,we demonstrated that the SA-inducible SsRss1 has transcriptional activity and played an essential role in SA stress responses inS.scitamineum,and contributed to virulence (Figs.5 and 6). To the best of our knowledge,this is the first observation that SA tolerance of a pathogenic fungus contributes to its pathogenicity.

Within the genusSporisorium,Rss1 similarities are from 82.55 to 85.51% between species,and between species of different genera within the order Urocystidales,Rss1 similarities are from 75.08 to 75.85% (Fig.1-B).Determined by the structural similarity,the function of SsRss1 is similar to UmRss1 in that they are both induced by SA. However,the profound difference between these proteins are that SsRss1 is required for full virulence inS.scitamineum,but UmRss1 not required for virulence inU.maydis(Rabeet al.2016).

SA is a crucial signaling molecule in the activation of plant defense responses (Ding and Ding 2020;Jandaet al.2020).In a healthy plant,the SA content is maintained at an extremely low level;however,its level can undergo significant upregulation in response to biotic or abiotic stresses (Coquozet al.1998). In this regard,the decline of virulence,including the delay in whip development (Fig.6) and a significant portion of infected plants unable to develop into the whips (Table 2),exhibited by ΔSsRSS1mutants fitted well with the assumption that theSsRSS1mutant may suffer from SA stressinplanta(Houet al.2022). It is speculated that the fitness of the ΔSsRSS1mutants might have been jeopardized by the SA stress from the sugarcane plants.This is in sharp contrast to that seen with the maize smut fungusU.maydis,whereRSS1deletion does not affect its pathogenicity (Rabeet al.2016).Therefore,targeting SsRss1 may be a potential strategy for the control of sugarcane smut.

AlthoughSsSRG1was also induced upon SA stress,partially mediated by SsRss1 (Fig.5),deletion of this gene did not seem to impair the SA tolerance of the fungus nor the sporidial growth and sexual mating (Appendices CE),suggesting that it does not participate in resistance to SA stress. It is likely thatSsSRG1may not play a role inS.scitamineumpathogenicity. Furthermore,the gene responsible for degradation of SA has yet to be identified.

5.Conclusion

In the present study,we identified an ortholog of theRSS1gene in the sugarcane smut fungusS.scitamineumand investigated its functions using a gene disruption approach. The results indicated thatSsRSS1is dispensable for basidiospore morphogenesis,budding,growth,and sexual mating,but contributes toS.scitamineumSA stress tolerance and virulence.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31872635),the Guangxi Key Laboratory of Sugarcane Biology,China(2018-266-Z01),and the Department of Science and Technology of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region,China (AD17129002). We are grateful to Dr.Meng Jiaorong of Guangxi University,China for the technical assistance with the sugarcane tissue culture.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendicesassociated with this paper are available on https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jia.2022.10.006

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年7期

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年7期

- Journal of Integrative Agriculture的其它文章

- Understanding changes in volatile compounds and fatty acids of Jincheng orange peel oil at different growth stages using GC-MS

- Untargeted UHPLC-Q-Exactive-MS-based metabolomics reveals associations between pre-and post-cooked metabolites and the taste quality of geographical indication rice and regular rice

- A double-layer model for improving the estimation of wheat canopy nitrogen content from unmanned aerial vehicle multispectral imagery

- The potential of green manure to increase soil carbon sequestration and reduce the yield-scaled carbon footprint of rice production in southern China

- lmprovement of soil fertility and rice yield after long-term application of cow manure combined with inorganic fertilizers

- A novel short transcript isoform of chicken lRF7 negatively regulates interferon-β production