The Historical Fiction Based on True Stories: An Analysis of the Menghui Gushu by Huang Jianhua with the Aid of Historical Records and Archaeological Objects of Art

Tang Lin*

Sichuan Academy of Social Sciences

Abstract: The Gushu Chuanqi [Legend of Ancient Shu] trilogy is historically grounded, although it is largely fictional.Five characteristics of the society represented in the trilogy, i.e., walled cities, sacred statues, silk fabrics,burials, and pottery, were examined with the aid of related historical records and archaeological objects of art unearthed in Sichuan.This paper made a comparative study of these things with their respective textual descriptions in the Menghui Gushu [Ancient Shu Revisited in the Dream],the first volume of the Gushu Chuanqi [Legend of Ancient Shu] trilogy by Huang Jianhua.The results support the assertion that the trilogy is not a free interpretation of history but historical fiction based on true stories.

Keywords: ancient Shu/ancient Sichuan, historical records, archaeological objects of art,comparative study

TheGushu Chuanqi[Legend of Ancient Shu] trilogy,which was published in 2021 by Sichuan Fine Arts Publishing House, consists of theMenghui Gushu[Ancient Shu Revisited in the Dream], theJinsha Chuanqi[The Legend of Jinsha], and theWuding Beige[An Elegy to Five Strong Men].This lengthy trilogy, involving numerous historical figures, is the first full-length novel on the history of ancient Shu, which spanned a thousand years and went through five dynasties from Cancong, Baiguan, Yufu, and Duyu, to Kaiming (partially overlapping with the reign of Lord Bing, the first king of the Ba state).Admittedly, the trilogy is largely fictional, and is based on a few historical records, such asShuwang Benji[Biographies of the Kings of Shu]①Shuwang Benji [Biographies of the Kings of Shu], also called Shu Benji or Shuji, is a chronicle of the ancient state of Shu in present-day Sichuan.The book is believed to have been compiled by Yang Xiong (53 BC–AD 18) of the Western Han Dynasty.The book was already lost during the Song period (960–1279),but fragments of it are quoted in some literary works by men of letters of the Tang and Song dynasties, with over a score of quotes coming down the ages.by Yang Xiong of the Western Han Dynasty (202 BC–AD 8), andHuayang Guo Zhi[Chronicles of Huayang] by Chang Qu of the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317–420).Although there is not much relevant information, except for some vague words in the historical records (Huang, 2021a, pp.514–515).②Regarding the starts and durations of these dynasties, there are only academic deductions, which can be found in the postscripts of the trilogy by Huang Jianhua (2021a, 2021b).Nevertheless, Huang’s narrative (particularly descriptions concerning the social customs and objects of ancient Shu) did not come out of thin air, but was inspired by by archaeological discoveries in Sichuan over the ages.The trilogy has had many positive reviews.For example, some say that it fills the vacuum in the historical writing of ancient Shu.As a long-term researcher of the history of fine arts (the history of fine arts in Sichuan in particular), I am to share my view on theGushu Chuanqi[Legend of Ancient Shu] trilogy, with a special focus on Volume oneMenghui Gushu[Ancient Shu Revisited in the Dream] with the aid of related historical records and archaeological objects of art.

The “wenxian” [literature] refers to pieces of writing on a particular subject, while “shiliao”[historical source] refers to things that can be used as a basis for historical research and discussion.Therefore, the compound “wenxian-shiliao” [historical record] in Chinese refers to written sources for historical research and discussion.

Archaeology of fine arts, which is about ancient history, aims to rebuild the ancient society and culture by using various artworks as physical materials.This branch of archaeology covers archaeological objects of art from the Paleolithic through various historical eras.What do fine arts refer to in this paper? Fine arts here should be understood in a traditional sense, that is,“general fine arts,” which fall into four main categories: painting, calligraphy, architecture, and sculpture.Physical objects are the concrete material existence of the four categories.

Figure 1.Cover of the Menghui Gushu [Ancient Shu Revisited in the Dream] by Huang Jianhua

Since there are countless historical records and archaeological objects of art related to ancient Shu, it is impossible to mention them all.This paper only focuses on five types, i.e., walled cities,sacred (bronze) statues, silk fabrics, burials, and pottery, to analyze textual descriptions in theMenghui Gushu[Ancient Shu Revisited in the Dream], the first volume of theGushu Chuanqi[Legend of Ancient Shu] trilogy.All of the five types belong to “general fine arts.” Walled cities and burials are of the architectural art category; sacred (bronze) statues, silk fabrics, and pottery are of the arts and crafts category (or rather, metal arts, textile arts, and pottery arts) (Tang, 2015).Chronologically, the five types came from three historical periods: the reign of the House of Cancong of Shu (presumed to be the same period as that of Emperor Ku, Yao, and Shun, after the Yellow Emperor), the reign of the House of Yufu of Shu (presumed to have lasted through Xia,Shang, and Zhou dynasties), and the reign of the House of Lord Lin of Ba.

Walled Cities

A walled city, referring to a large human settlement enclosed by a wall, is an umbrella term here for cities and towns in ancient China.In ancient times, walled cities were strongholds of political rule, and also representations of the economic, cultural, and technological achievements of the times.In the era of slavery, when kingship was paramount, a state’s capital was its political center and had the largest urban area.The earliest known cities in China appeared on the land of Qi (present-day Shandong) of the Longshan culture between 4,000 and 4,600 years ago.Among them was Chengziya, an archaeological site in Longshan town under the administration of Zhangqiu city, Shandong province (Li, 1992, p.628).

In theGushu Chuanqi[Legend of Ancient Shu] trilogy, Cancong, founder of the Shu state,headed the migration to the plain from the Min River valley in Sichuan.When they reached the confluence zone of rivers, they decided to settle on higher ground nearby.It was at that time that Cancong made a major decision, that is, to build a city.In Huang’s imagination, the city was built under Cancong’s leadership as follows:

Cancong decided to build a city.So, his men drew on local resources around their settlement and rammed down the earth hard to build a high city wall.This large earthen city was in a square shape outlined by a tall and wide wall, which was as magnificent as a dike.The tribe lived in the earthen city, and could make full use of its multiple functions to defend themselves against wild animals and prevent floods.More importantly, compared with scattered settlements in the wilderness, a clustered settlement in a walled city could better unite people to accomplish big causes, such as the later establishment of the Shu state (Huang,2021a, p.48).

The narrative is echoed by some historical records.In “Kao Gong Ji” [Records of Examinationof Craftsman] ofZhou Li[The Rites of Zhou], a classic work compiled in the pre-Qin period, there is a description of the layout of the king’s capital:

The craftsmen built the city as a square of nineliper side and each side with three gates.Within the city, there were nine north-south arteries and nine east-west boulevards.The roads of the north-south arteries measured nine axle-lengths across.On the left was the ancestral temple; on the right, the altars to soil and grain.In the front was the royal court, and behind it,the marketplace.Both the marketplace and the royal court measured 100 steps (c.140 m) per side.

Also, there is a mention of a city building inWu Yue Chunqiu[Spring and Autumn Annals of Wu and Yue], an unofficial history by Zhao Ye from the late Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220).It reads, “Gun built a citadel in order to guard the ruler, and constructed an outer city wall to give the people somewhere to live.” Admittedly, these records date back over 1,000 years from the era of Cancong, and are not about the ancient Shu state.Still, they can serve as useful guidelines.

Archaeological objects of art in this regard are abundant in Sichuan.So far, six prehistoric city sites have been found in Sichuan, and all are located in the Chengdu Plain.They respectively are the Baodun site (at present-day Baodun village, Longma township, Xinjin district, Chengdu), the Mangcheng site (at present-day Mangcheng village, Qingcheng township,Dujiangyan city, Chengdu), the Yufu site (at present-day Yufu village, Wanchun town,Wenjiang district, Chengdu), the Pixian site (at present-day Gucheng village, Gucheng town, Pidu district, Chengdu), as well as the Shuanghe site and the Zizhu site (at present-day Shuanghechang,Shangyuan township, and present-day Zizhu village, Liaoyuan township under Chongzhou city, Chengdu) (Ma, 2003, p.112).The absolute ages of the six prehistoric city sites range from about 2,875 to 4,500 years ago (Meng, 1988), and they all belong to the Baodun culture (Jiang et al.,1997).Walled cities of this period in the Ba-Shu region had similar patterns, with rammed walls in irregular rectangular shapes (except the site of Yufu, whose wall is in an irregular polygonal shape).From the six city sites, it can be inferred that prehistoric cities in Sichuan tended to be built on higher ground near rivers, that the longest sideof their rectangular wall was often parallel to the river course and the higher ground trend, and that the urban outlines were nearly rectangular or square (Zhang, 2015, p.32).During this time,“western Sichuan was the rainiest area,” and “flash floods wreaked havoc across the Shu state,forcing people to live like fish in the river,” wrote Chen Shen inShi Xi[Stone Rhinoceros].Given that, the above architectural patterns were for flood prevention purposes.It should be noted that it was not until many centuries after the reign of Cancong that Li Bing, administrator of Shu Prefecture, built the Dujiangyan project to tame the floods.In Cancong’s era, the Chengdu Plain was vulnerable to flooding.

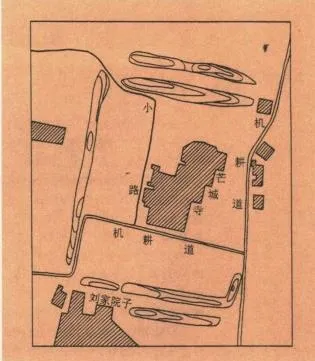

Figure 2.Plan of the Mangcheng site, a prehistoric city in Sichuan province① Source: Prehistoric Chinese Cities by Ma Shizhi (2003, p.115).

The exact location of the ancient city built by Cancong on the Chengdu Plain remains unknown, but one thing for sure is that the ancient city has all of the above characteristics.Considering the historical fact that Cancong of Shu led his people to the plain by traveling down the Min River, his city was probably built in the area of present-day Dujiangyan in Sichuan.It happens that there is the site of a prehistoric city called Mangcheng in Dujiangyan.The Mangcheng site is located at Mangcheng village, Qingcheng township, some 12 kilometers south of downtown Dujiangyan.The site is a slightly irregular rectangle (10° east of north).The inside of the city is higher than the outside by about 0.3 centimeters.The city consists of two parts, namely, the outer city and the inner city, each of which is enclosed by a wall.The outer city is about 360 meters long from north to south, and 340 meters wide from east to west, covering an area of about 120,000 square meters; the inner city is about 290 meters long from north to south, and 270 meters wide from east to west, covering an area of about 78,000 square meters.The existing outer wall has four sections, i.e., the 238 meters north section,the 36 meters east section, the 224 meters south section, and the 224 meters west section.The existing inner wall is 8–13 meters in width, and 1–1.2 meters in height (Wang & Jiang, 1996).Different from later wall construction methods, their construction method involved piling up rammed earth into a slope-shaped wall.The wall was built of rammed earth on flat ground in a sloped shape.According to Duan Yu, a historian, the prehistoric city site at Mangcheng village was a crucial place, where water from the upper course of the Min River was channeled to the Chengdu Plain for irrigation, and its era also roughly coincided with the time when Cancong and Yufu migrated from the Min Mountains to the Chengdu Plain in historical records.

In short, Huang’s narrative of city-building is historically grounded.Also, Huang’s narrative highlights two key points on city building in the early years of Shu: a) build a high and strong wall to prevent floods according to the trend of the nearby rivers, and b) build a city or town on higher ground near the confluence zone of rivers according to the local terrain.

Sacred Statues

According to theXiandai Hanyu Tujie Cidian[An Illustrated Dictionary of Modern Chinese Language], which was compiled by Shuoci Jiezi Cishu Yanjiu Zhongxin [Center forWord Interpretation and Dictionary Studies] and published by Sinolingua in 2017, the Chinese term “shenxiang” [sacred statue] has two meanings: a) effigy of the deceased (old use), and b)portrait or statue of gods/buddhas.

In order to dispel the hatred between tribes and unite the people, King Yufu (the second king of Shu after Cancong) decided to cast sacred statues of Cancong and numerous dead tribal chiefs.In this case, “sacred statue” refers to the effigy of the deceased.

King Yufu asked craftsmen to cast (bronze) statues of King Cancong and numerous dead tribal chiefs to form a group of sacred statues.This vast project was something unprecedented…The Shu craftsmen, in a fever of excitement, gave full play to their imagination and worked hard in cooperation with a due division of labor.Soon, they completed the first statue of King Cancong in an imperial robe and crown in the middle of worshipping the deities.The statue highlighted his grave and dignified bearing.Then,a second statue was cast, featuring protruding eyes.Following that, the craftsmen carefully conceived the images of numerous dead tribal chiefs, with some wearing hats, some braids,and some hairpins, forming a group of vivid statues with different looks and in varied postures.It took months to complete the design and casting (Huang, 2021a, p.317).

Relevant information is easy to find in historical records.According to “Shan Quan Shu”ofGuangzi, “Tang of Shang minted coins with metal from the Zhuang Mountain.” The Zhuang Mountain refers to a copper mountain in Yandao, and is now the copper mine in Yingjing.Whether this quote is true remains to be proven, but what is certain is that Yandao was known to the Central Plains for its copper deposits.According to “Shu Zhi” [Records of Shu] ofHuayang Guo Zhi[Chronicles of Huayang], “There are many precious deposits in Sichuan, such as copper, iron, lead, tin, and hollow azurite.” Both lead and tin were important raw materials for making bronze.Hollow azurite was probably the principal raw material used by people in the ancient Ba-Shu region to make bronze.In the tenth volume ofBencao Gangmu[Compendium of Materia Medica] by Li Shizhen, there is a quote fromMingyi Bielu[Supplementary Records of Famous Physicians]:

Hollow azurite occurs naturally with copper in the valleys of Yizhou (present-day Chengdu, Sichuan) and in the mountains of Yuexi (present-day Liangshan, Sichuan).It is produced by weathering copper ore deposits.It has a “hollow heart” and normally, but not necessarily, appears in the third lunar month.It can be mixed with copper, iron, lead, and tin,to make certain metallic substances.

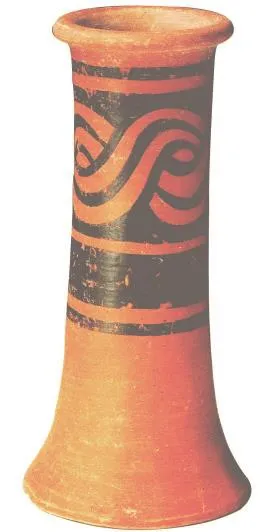

There is no shortage of archaeological objects of art made of bronze in Sichuan, which can be exemplified by a group of bronze sculptures unearthed from Sanxingdui.In 1986, local workers accidentally found sacrificial pits containing a large number of bronze sculptures dating back to the Shang Dynasty over 4,000 years ago.Bronze sculptures found in the first and second sacrificial pits included human figures, human heads, human faces, human-faced masks, and animal-faced masks.They have different shapes and postures, such as a kneelingfigure, a standing figure, a half-length figure in a beast-headed crown, a human figure with a bird’s claw-shaped feet, a small kneeling figure holding azhangblade, a kneeling figure on a horn-shaped base with azun(wine vessel) on top of the head, and a large sacred tree.There were a total of 242 bronze sculptures, including eight human figures, 57 human heads, 34 masks, 109 pairs of eyes, and 34 animals.①Source: Contrastive Table of Bronze Vessels Unearthed from Pit 1 and Pit 2 of Sanxingdui and Those from the Sacrificial Zone of Jinsha in “Jinsha Yizhi Jisiqu Chutu Yiwu Yanjiu” [Researches on the Artifacts Unearthed from the Sacrificial Zone of Jinsha Site] by Shi Jinsong (2011).They are by far the largest group of bronze sculptures in China, both by number and by shape (Yao, 2004).

In terms of craftsmanship, the exquisite bronze sculptures of Sanxingdui show that ancient Shu people excelled at bronze casting.As early as the late Shang Dynasty, they had already mastered two bronze-casting processes:separate casting and integral casting, and also began to use methods, such as brazing, hot patching, and riveting.They did this a few hundred years earlier than the people in the Central Plains (Xing & Zheng, 1989).Their superb casting techniques and procedures reflect the advancement of metal smelting and casting.In terms of design, most of the bronze figures,heads, and masks of Sanxingdui were cast realistically.These sculptures, realistic yet larger than life, highlight the diversity, completeness, and artistry of bronze design of that time.Some bronze figures are so lifelike that one can tell their tribes and classes by their distinct facial features, hairstyles, and clothing.Some bronze figures are more expressive and exaggerative.For example, there is a huge human face with protruding eyes, a curved and elongated mouth,and big stretching ears, creating an exceptionally grotesque and overwhelmingly awe-inspiring vibe.Others are a combination of realism and distortion, with finely chiseled features for vivid texture, and a few elements of exaggeration for artistic appeal.They are both concrete and abstract, realistic and romantic, powerful and mysterious, as well as man-like and supernatural.In terms of decorative art, the decorative patterns on the bronzes can be divided into two types:animal-shaped patterns and geometric patterns (Chen, 1990).According to Duan Yu (1991),judging from their cultural origin, these bronze sculptures should be the images of the ruling group of the ancient Shu state headed by King Yufu.

Evidently, the above narrative by Huang Jianhua is based on the bronze sculptures unearthed from Sanxingdui.In fact, bronze sculptures of Sanxingdui were already the theme of Huang’searly publications, such asSanxingdui: Zhenjing Tianxia De Dongfang Wenming[Sanxingdui:An Oriental Civilization That Shocked the World] andSanxingdui(Korean version).

Figure 3.A bronze mask with protruding eyes from the Shang-Zhou period at the Sanxingdui Museum in Deyang, Sichuan

Silk Fabrics

Silk fabrics refer to textiles made of natural silk (mainly mulberry silk, partially wild silk,and cassava silk).In ancient times, farming and sericulture were essential for a state and its people to grow rich and strong, as silk fabrics had long been the nobility’s main material for clothing and an important export.During the Three Kingdom’s period, brocade, a special silk product made in the state of Shu, was deemed a major strategic material by Zhuge Liang,chancellor of Shu.

The term “silk fabrics” frequently appears in Huang’sMenghui Gushu[Ancient Shu Revisited in the Dream] to help depict how Xiling, wife of Cancong, popularized sericulture among women of her tribe, and spread it to other tribes and people on the plain for a bigger harvest.For space reasons, just one example is given below:

In preparation for this grand sacrificial rite (after migration to the plain), Xiling (wife of Cancong) hunted out a newly made silk gown for Cancong, washed it clean, and embroidered a cloud pattern beneath the existing dragon-and-horse pattern, making the gown even more gorgeous.As soon as the tribe moved to the plain, Xiling began to popularize sericulture among women of her tribe.The fertile land and humid climate created favorable conditions for mulberry growth on the plain.Tender mulberry leaves made sure that silkworms were well-nourished and that their cocoons were particularly full.Subsequently, silk fabrics made of such cocoons were exceptionally beautiful and lustrous.Sericulture soon became a novelty to smaller tribes in the vicinity, and more and more people came to learn the technique from the Shushan tribe.Thus, sericulture quickly spread across the plain (Huang, 2021a, p.317).

The development of sericulture in Sichuan is well documented.The Sichuan Basin, along with its surrounding areas (known as the state of Shu in ancient times), has a long history of sericulture and silk production, and is one of the birthplaces of China’s silk culture.That explains why the Shu state is also known as the “ancient state of Cancong,” meaning an ancient state ruled by God of the Bluegreen Clothes/Sericulture.The emergence of the Ba-Shu civilization was marked by sericulture and silk production.As early as remote antiquity,the Shu people had already learned sericulture, silk reeling, and brocade weaving.According toShuowen Jiezi[Discussing Writing and Explaining Characters], the Chinese character “蜀”[shu] means “a silkworm on a ‘kui’ [mulberry] leaf.” The interpretation of “kui” as mulberry is given inErya, the first surviving Chinese dictionary.As it is said in “Dong Shan, Odes of Bin” of theBook of Poetry, “Creeping about were the caterpillars, all over the mulberry grounds.” These historical records document that the state of Shu (ancient Sichuan) derived its name from sericulture and that sericulture originated in the state of Shu (Fu, 2006, p.41).In the late Neolithic, the Shushan tribe and the Cancong tribe in the state of Shu were known for their sericulture.Legend has it that it was Fuxi that discovered wild silkworms on mulberry leaves when he “found things for consideration at a distance in things in general”in present-day Langzhong, Sichuan.The mulberry Mulberry tree was deemed the sacred tree of the estate of Leizu, a legendary Chinese empress and wife of the Yellow Emperor.Leizu was also from the Xiling tribe.According to tradition, she domesticated wild silkworms previously discovered by Fuxi in a grove of mulberry trees, and later initiated a silk culture by inventing silk reel and silk loom in China.Leizu’s native place was in present-day Yanting county (Sichuan), which is less than 100 kilometers away from Langzhong as the crow flies.Because of Fuxi’s discovery of wild silkworms on mulberry leaves in Langzhong (near Yanting) and the “Silkworm Mother” Leizu’s domestication of wild silkworms in a grove of mulberry trees in Yanting, Yanting became the source of Chinese silk culture and the starting point of the (Northern and Southern) Silk Road.The legend of Matou Niang (lit.“woman with a horse head”) gives another explanation regarding the beginning of sericulture, raw silk reeling, and silk and brocade weaving in Sichuan.Her poignant story also mirrors a long history of sericulture in Sichuan.According to “Ba Zhi” [Records of Ba] ofHuayang Guo Zhi[Chronicles of Huayang], “Yu (the Great) requested the presence of lords of vassal states at Kuaiji.Tens of thousands of lords, including those from the states of Ba and Shu, went there with gifts of ‘yu’ [jade articles] and ‘bo’ [silk products].” It can thus be inferred that ancient people in Sichuan 4,000 years ago were already able to produce “bo,” which was the earliest form of “jin” [brocade] (Huang, 2011, p.1).

There are also silk relics as archaeological objects of art.For example, many scholars,including Huang Nengfu, a professor at the Academy of Arts and Design, Tsinghua University,believe that the world-famous standing bronze statue excavated from the Sanxingdui Ruins site was originally clothed in silk.Among the findings of further archaeological excavations at the sacrificial zone of Sanxingdui in 2021 were silk fabric residues in some ritual pits.Moreover,silk protein was found in multiple soil samples from the ritual pits.The discovery shows that more than 3,000 years ago, silk fabrics were already in use in the Sanxingdui kingdom.

The above evidence tallies with Huang’s narrative of how Xiling introduced and popularized sericulture and silk production among the Shu people.In other words, Huang’s narrative is based on solid historical facts of a particular period.

Burials

A burial is a form or act of burying a dead body.Ancient burial customs varied according to the times and places, including but not limited to in-ground burial, cremation, and water burial.Modern archaeological findings prove that as early as the Paleolithic period, the ancestors consciously buried the dead in the ground and that in the Neolithic period, it became the normto bury the dead in a collective burial pit (Xie, 2018, p.162).

Upon the death of Cancong’s father in the Min River valley, Cancong and his family held a grand funeral for the late chief in accordance with the tradition of the Shushan tribe.The burial ceremony was depicted by Huang Jianhua as follows:

The Shushan tribe had its own (funeral) tradition, with burial objects and coffin pits unique to itself and distinctive from other tribes.After the chief was dead, Cancong had a sarcophagus made for him, and placed the sarcophagus containing the remains in a coffin chamber for a few days.When the auspicious day came, a grand funeral was held for the late chief.Then,the sarcophagus was carried to the graveyard, where it was put into an already prepared outer coffin made of stone slabs and buried in a sacrificial ritual.The origin of such a burial could be traced back to the era of Cancong’s grandfather (Huang, 2021a, p.18).

The abovementioned burial is the famous “sarcophagus” in ancient Sichuan.The so-called“sarcophagus” (also known as “stone coffin,” “stone slab burial,” or “stone slab tomb”) is a type of archaeological and cultural relic characterized by a coffin chamber piled up with stone slabs or stone blocks (Shi, 2009, p.177).

There are historical records on the sarcophagus in Sichuan, and the earliest mention can be found in “Shu Zhi” [Records of Shu] ofHuayang Guo Zhi[Chronicles of Huayang].It reads:

After King You of (Western) Zhou violated the laws of the imperial court, the head of the Shu region took the opportunity to proclaim himself king.Thus, Cancong, Marquis of Shu,who had protruding eyes, became the first king of Shu.When he died, his body was put into a sarcophagus inside an outer stone coffin.This way of burying was followed by people in the state of Shu.

Thus, “sarcophagus” was known for being the graves of men with protruding eyes.

Sarcophagi as archaeological objects of art have also been found in Sichuan.The Yingpan Mountain site south of Fengyi town (Mao county, Aba Tibetan and Qiang autonomous prefecture, Sichuan) is by far the earliest and also the largest complex of sarcophagi ever discovered in China.There are tens of thousands of sarcophagi distributed in an area of 150,000 square meters (Chen, 2005).Most of the sarcophagi there were placed in vertical earth pits.These sarcophagi were all roofed but bottomless, and both the pits and sarcophagi were customized to the physical builds of the deceased, whose remains and grave goods were directly placed on the earth floor.These sarcophagi, pilled up with stone slabs of different sizes and thicknesses, were all without base slabs.Flagstones were used as side slabs, front slabs,and cover slabs.Small flat stones can be found at the bottom of side slabs for reinforcement purposes.In most cases, there is a thin bed of clay on the tomb bottom protecting the remains,and filled earth on the coffin top.Coffin chambers are generally 1–1.8 meters in length, and 0.2–0.4 meters in width, and there are even dual chambers.The Shushan tribe mentioned in the fiction originated in Diexi town (also known as Canling town) in Mao county.As Diexi is only about 50 kilometers away from the Yingpan Mountain, exchanges between the two placesshould be easy and unencumbered, even in the era of Cancong.

Sarcophagus as a form of burial was mainly found in a half-moon-shaped belt of cultural dissemination stretching along the borderlands from northeastern China, through northern China, Gansu, and Qinghai, to western Sichuan and eastern Tibet.The upper reaches of the Min River in Sichuan remain the region with the most densely distributed and numerous sarcophagi in China, and sarcophagi discovered and excavated there account for more than half of the total number in southwestern China (Li, 2008, p.75).Many archaeologists have done research on sarcophagi in this region, including Feng Hanji and Tong Enzheng.The sarcophagus, popular in the Western Sichuan Plateau, was the burial custom of the Diqiang people (Duan, 2010, p.325).

Huang’s narrative is in line with the then reality.

Pottery

Pottery is a major cultural feature of the Neolithic period, and is also the most prominent epitome of primitive artistic achievements in the history of arts and crafts (Wang, 1994, p.16).In the prehistoric period, pottery, which was made by ancient people from raw clay through kiln firing, served for both practical and aesthetic purposes.This Neolithic invention is epochmaking in human history.Pottery came into being following the emergence of food cooking(Zhang, 2017, p.9).

Huang Jianhua mentioned pottery making when detailing the founding of the Ba state in theMenghui Gushu[Ancient Shu Revisited in the Dream].Wuxiang (also known as Lord Lin, who later became the founder of the Ba state) made unsinkable pottery ships by firing clay ships somewhere in present-day Jiajiang, Chongqing, in the early days of the Ba state.It is presumed that the Ba state was established by Lord Lin after the Cancong era and that it co-existed with the Yufu dynasty in ancient Sichuan.Huang Jianhua wrote:

Exhausted, Wuxiang dozed off.In the dream, he went to a smoky place, where some old men were busy making and firing pottery.Sand clay was molded into a variety of vessels,which were then fired with dried firewood into pottery jars, pots, bowls, and cups for daily use.Wuxiang was looking at the fired pottery, fascinated and excited.Could this be a sign from gods (Huang, 2021a, p.335)?

According to historical records, the Chinese people were among the earliest in the world to have mastered the pottery-making technique, and they were the first to put the pottery-making technique down in writing.There were mentions of pottery making in some ancient Chinese classics, such as “Shennong promoted the practices of agriculture and pottery making” inYi Zhou Shu[Lost Book of Zhou], and “(Shun) made pottery by the Yellow River” in “Zashi Yi”[Miscellaneous Affairs 1] ofXinxu[New Order].As early as the Yellow Emperor’s era, there was a special post calledtao zheng[chief potter] in charge of pottery making.Early in the Neolithic period, the ancestors of the Chinese had already learned how to mix water and soilinto plastic clay, which was molded and fired into pottery in the kiln (Ruan, 2008, p.428).The pottery-making technique was the most outstanding and diverse art creation of the Neolithic period,and is a precious heritage left by the ancestors of the Chinese nation in art history (Bo, 2003, p.3).

Figure 4.Painted earthenware bottle unearthed from the site of Daxi Neolithic culture in Wushan county, Chongqing① Source: Pictorial Encyclopedia: Ba-Shu Culture by Tan Jihe and Duan Yu (1999, p.108).

Regarding archaeological objects of art, a pottery sherd with early Neolithic characteristics was unearthed at a stratum formed 7,500 years ago in Yifupu, Fengjie county, Chongqing (part of the Ba state in ancient times) in the 1990s.A lot of pottery was excavated from the site of Daxi Neolithic culture in Wushan county, Chongqing Municipality, and the pottery falls into four categories: red pottery, gray pottery, black pottery, and painted pottery.Of the pottery unearthed there, red earthenware, which was coated and fired at 800–870 °C, features a smooth and delicate surface with a reddish hue; some earthenware has a unique style of the red outer surface and black inner surface, due to “reversed”firing, which caused insufficient oxidation of the inner surface but complete oxidation of the outer surface (Shao, 2005, p.44).

Huang’s narrative of how Lord Bing, founder of the Ba state, made pottery ships was well-grounded and persuasive.

Conclusion

This paper examined the above five types of things of ancient Shu with the aid of related historical records and archaeological objects of art unearthed in Sichuan, and made a comparative study of these things with their respective textual descriptions by Huang Jianhua.It is thus concluded that theGushu Chuanqi[Legend of Ancient Shu] trilogy by Huang Jianhua is not a free interpretation of history but historical fiction based on true stories.Or, to put it another way, the trilogy is historically grounded, although it is largely fictional.Huang Jianhua is an accomplished scholar and prolific writer with a number of academic publications(monographs in particular), which become an edge not possessed by most historical writers.His representative works includeHuayang Guo Zhi Gushi Xinjie[A New Interpretation of Stories in the Chronicles of Huayang],Si Lu Shang De Wenming Guguo[Ancient Civilizations along the Silk Road], andLiterary Masters in Chengdu.

“Cancong and Yufu of ancient dates were kings of the land with frontiers,” said Li Bai in his poemShu Dao Nan[Ode to Hard Roads to Sichuan].Ancient Shu was a mysterious statein what is now Sichuan province.Due to a lack of written records, ancient Shu often leaves an impression of being mysterious (Huang, 2021b, p.493).It is not practical for young people today (except researchers and those who are truly interested in the history of ancient Shu) to read such ancient literature asShuwang Benji[Biographies of the Kings of Shu] by Yang Xiong andHuayang Guo Zhi[Chronicles of Huayang] by Chang Qu, because of the high threshold of classical literature and insufficient reading time.Given that, Huang’sGushu Chuanqi[Legend of Ancient Shu] trilogy, which is easy to read and fascinating, offers readers an opportunity to approach ancient Shu.

A straw shows which way the wind blows.TheGushu Chuanqi[Legend of Ancient Shu]trilogy is historical fiction based on true stories.

Contemporary Social Sciences2022年2期

Contemporary Social Sciences2022年2期

- Contemporary Social Sciences的其它文章

- The Belt and Road Initiative: Multilingual Opportunities and Linguistic Challenges for Guangxi, China

- Research on the Impact of Venture Risk Tolerance on R&D Investments:Based on Entrepreneur Ability

- Research on Big Data Platform Design in the Context of Digital Agriculture: Case Study of the Peony Industry in Heze City, China

- A Preliminary Study of Embedded Supervision Thoughts: Based on a Distributed Financial System

- Financial Knowledge, Capability to Guard Against Risks, and Rural Households’ Selection of Financial Assets: An Empirical Study Based on Rural Households in China

- A Brief Introduction to the English Periodical of Contemporary Social Sciences