Surgical perspective on treatment of pediatric undifferentiated sarcoma of the liver

Ana M. Calinescu, Barbara E. Wildhaber, Florent Guérin

1Division of Pediatric Surgery, University Center of Pediatric Surgery of Western Switzerland, Geneva University Hospitals,Geneva 1205, Switzerland.

2Pediatric Surgery Unit, Bicêtre Hospital, Université Paris-Saclay, Paris 94275, France.

Abstract Surgical resection and chemotherapy are the mainstay of the treatment for undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver. Whether neoadjuvant chemotherapy should be systematically performed is a matter of debate;perioperative morbidity and mortality should be carefully weighed against chemotherapy-associated complications. In order to manage undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver and to allow for accurate outcome analysis, there is a clear need for standardization of disease extent as well as for a risk stratification system, including the PRETEXT grouping system, patient age, and tumor size.

Keywords: Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver, staging system, positive margins, neoadjuvant chemotherapy

INTRODUCTION

Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver (UESL) is the third most frequent liver malignancy in children. Its peak of incidence lays between that of hepatoblastoma (young children) and hepatocellular carcinoma (older children)[1]. Most children who develop UESL are aged 6 to 10 years[2]. The clinical presentation is often non-specific: an abdominal mass with or without abdominal pain can be observed,fever if hemorrhage, and/or necrosis, as well as secondary symptoms (e.g., weight loss, anorexia,etc.)[3].

Laboratory findings are usually not specific (i.e., normal liver tests and negative neoplastic markers)[3].Radiological diagnosis might be difficult because of overlapping features with other pediatric liver masses;ultrasound may show a mass with mixed solid and cystic components and computed tomography usually depicts a large hypodense mass with multiple septations and solid nodules[3-5]. The cystic appearance might be misleading, causing delayed management[3]. UESL is often larger than 10 cm at diagnosis, with 75% of the cases located in the right liver lobe, 10% in the left lobe, and 15% in both lobes[3,6]. Pathological examination and immunohistochemical analysis of biopsy specimens, as well as of the surgical resection material, is the mainstay of diagnosis for UESL[7]. In contrary to other liver tumors such as hepatoblastoma and hepatocellular carcinoma, there is no universally agreed treatment of UESL. But two elements are constant and acknowledged within the worldwide used protocols: UESL is a chemo-sensitive tumor and complete surgical resection is of utmost importance. The aim of this perspective is to discuss the state-of-the-art surgical strategy of UESL as well as the necessity to define a new risk stratification grouping system for this particular pediatric liver malignancy.

TREATMENT PROTOCOLS

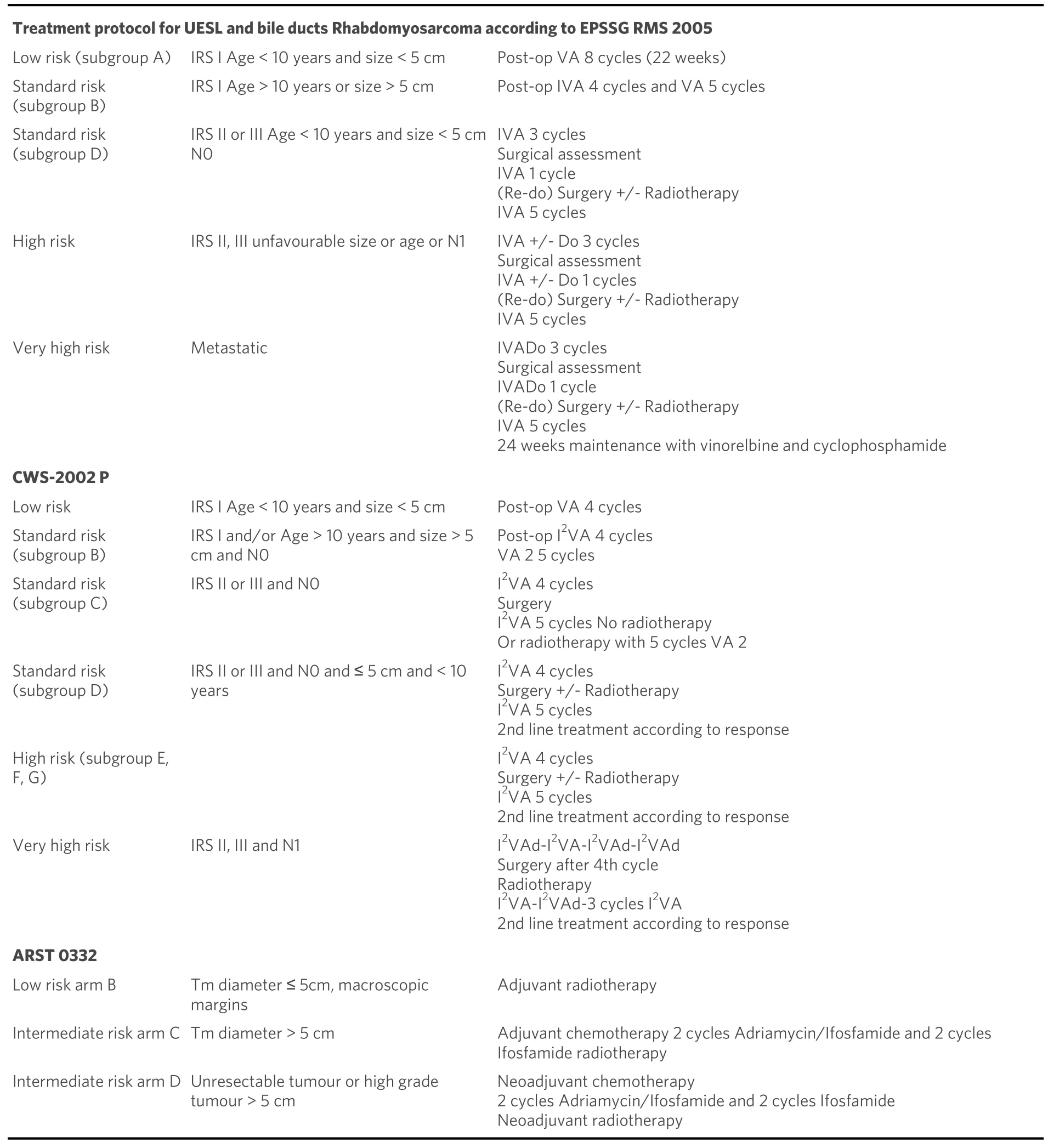

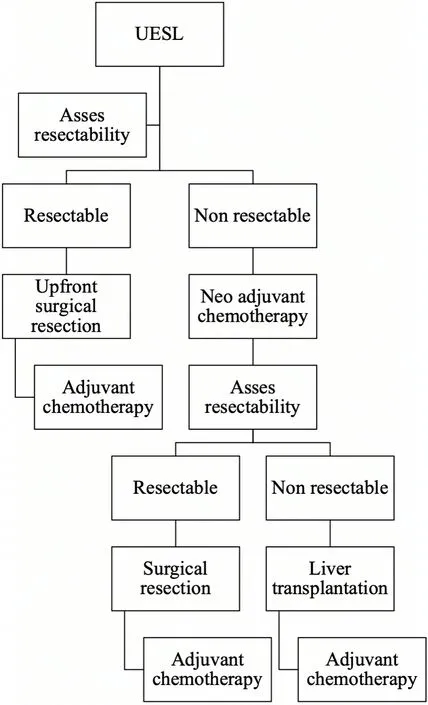

Treatment for UESL evolved from a surgery-only based treatment in the early 1980’s, when chemo- and radiotherapy was used only occasionally, to a multimodal treatment management plan including(neo)adjuvant chemotherapy[8]. But still, and as mentioned above, the management for UESL varies within different oncological societies, as further addressed below [Table 1]. Nonetheless, the general agreement is as follows: if the mass is resectable, an upfront surgical resection followed by adjuvant chemotherapy is advised; however, if the mass is deemed an unresectable mass, a neoadjuvant chemotherapy, reassessment,surgical resection or liver transplantation, and subsequent chemotherapy is recommended [Figure 1][9,10].

As for the timing of surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy within the different protocols of the different societies, the “European” treatment of UESL initially, between 1995 and 2005, followed the rules of theSocié té Internationale d’Oncologie Pédiatrique(SIOP) using the “Malignant Mesenchymal Tumors Protocol SIOP-MMT95”; from 2005, the protocol has changed to the RMS2005 EpSSG that evaluates surgical feasibility after the 3rd course and actually performs it after the 4th course[9]. The German CWS(Cooperative Weichteilsarkom Studie) also evaluates treatment response after 3 courses of chemotherapy,and if deemed feasible a definitive delayed surgery is performed after the 4th course; within both protocols,abdominal irradiation is recommended only if local control cannot be achieved otherwise[11]. The American Children Oncology Group (COG) uses different protocols; within the “soft tissue sarcoma protocol”, 5 courses of neoadjuvant chemotherapy are employed[10].

As for radiotherapy, the role and average dose in UESL is not well-defined[11]. Radiotherapy might help in preventing recurrence but its effectiveness as well as impact on survival is unknown yet[12]. Reports of its use in peritoneal dissemination confirm its feasibility but data is still scarce[13]. But still, the use of radiation therapy is reported to be as high as in 15% of the patients[12,14].

A case series dating from 2000, evaluating the role of transhepatic arterial chemoembolization (TACE) in liver tumors, showed that in two children with UESL TACE did not show any response to this type of therapy[15]. However, in a recent report of two cases, TACE combined with neoadjuvant chemotherapy with reduced dosage, allowed for significant reduction of tumor size. Zhaoet al.[16]consider that TACE might be used as a preoperative therapy in pediatric UESL where the tumor is initially deemed unresectable.

Unresectable tumors might benefit from the transarterial radioembolization as a bridge to resection or transplantation or as a less toxic, palliative treatment alternative[17]. Minimal data exists for this treatment option in pediatric liver malignancies[17,18].

Table 1. Treatment protocols for paediatric undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver (UESL)

As with other liver tumors, in the case of tumor rupture or spontaneous bleeding and if the patient is unstable, arterial embolization or, if feasible, complete upfront resection might be performed[9].

Figure 1. Decisional algorithm for the management of undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver (UESL).

THE ROLE OF PREOPERATIVE CHEMOTHERAPY

Preoperative chemotherapy has shown to reduce tumor size and minimizes the risk of intraoperative spillage or microscopic residue. Between 30% to 40% of the patients might not be amenable to a primary tumor resection and are subjected to neoadjuvant chemotherapy to facilitate a complete surgical resection[1,14]. In fact, after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, resectability has been reported to improve in up to 81% in recent series, with varied regimens that are basically used for other pediatric soft tissue sarcomas[11,19]. Another, less studied effect of the neoadjuvant chemotherapy is the percentage of tumor necrosis, which ranged between 70%-100% in a series of seven patients, even if the radiologic response was not as obvious as the pathologic response[9].

Despite the commonly recognized credo that in case of resectable UESL, surgery could or should be done upfront without neoadjuvant chemotherapy, some centers advocate preoperative chemotherapy regardless of the stage of resectability. Resections seem to become easier after chemotherapy, and thus are associated with a reduced morbidity. Nevertheless chemotherapy is also associated with multiple side effects: 5% and 8% after IRS III regimens 38 and 35, respectively, where two thirds of the complications were reported to be secondary to sepsis developed after neutropenia[20]; cardiac toxicity, metabolic complications, respiratory distress syndrome and central nervous system toxicity were less frequently described. Of note, within the EpSSG protocol the number of chemotherapy cycles remains the same even if upfront surgery is performed,which supports the safer attitude of preoperative chemotherapy[9]. Yet, there is not enough solid evidence to support the benefit of systematic neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus upfront surgery and larger prospective,multicentric studies are required to draw a conclusion.

SURGICAL STRATEGIES

The surgical challenges in the treatment of UESL are mainly related to the large size at the moment of diagnosis[10]. Fortunately, initial aggressive surgeries are less required nowadays, since, as stated above,neoadjuvant chemotherapy decreases tumor size and makes it more amenable to a more standard complete resection[20,21]. The most frequently performed surgical resections are hemihepatectomy (37%), followed by sectionectomy (28%) and trisectionectomy (10%)[12]. But to allow for proper patient management (i.e.,surgery planning), a preoperative staging system is needed.

UESL staging system

Regrettably, preoperative staging such as COG-staging or PRETEXT is not always mentioned in the literature[12], making interpretations and comparison of publications more difficult. One of the first series reporting on UESL usedIntergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Studyclinical grouping [Table 2][22]. In a series of 5 patients, the American COG stage was reported as stage I in 4 patients and stage II in 1 patient(preoperative rupture); no correlations could be found with this tumor staging given the small sample size[23]. PRETEXT staging was used for the UESL in only two series, a review of pediatric liver malignancies in Finland with 7 PRETEXT II-III tumors and a monocentric retrospective review of 6 PRETEXT II-III tumors. Again, given the small sample size, conclusions for tumor size correlation with survival were difficult to draw[10,24]. Finally, European prognosis groups are stratified according to theInternational Rhabdomyosarcoma Study group[9]. Given the heterogeneity of staging for UESL, no clear correlations between extent of disease and survival can be made. A uniform reporting with the PRETEXT grouping system might be helpful for the standardization of patient grouping, and subsequent patient management, and thus survival analysis. Additional data including age and size of the tumor, together with the PRETEXT grouping system, could be included in a new risk stratification protocol for UESL.

Positive resection margins

The significance of microscopic residuum is still debated. In a cohort of 103 patients of which 20 had positive microscopic margins, R1 resection did not seem to affect outcome, (P= 0.11), but the best survival rates are still reported for patients with negative margins 95% 5-year survivalvs. 83% 5-year survival for patients with positive margins (i.e., R0 resection)[11,12,23]. Nevertheless, the burden of treatment could not be evaluated in the 103 patient cohort of the American National Cancer Database[12], but consisted in 52%neoadjuvant chemotherapy in a smaller CWS cohort of 25 patients in which resection type impacted survival[11]. Again, larger, standardized studies focusing on the matter are needed to obtain a definite answer on the effect of microscopic margins on outcome.

Metastatic UESL

Although UESL metastases are seen in only 15% of cases[12], overall survival falls from 91% in patients without metastatic disease to 70% in patients with metastatic UESL[12]. The most common sites for metastasis are the lungs, adrenal gland, peritoneum, and pleura[12,25-28]. Cardiac metastases are found in 10%-25% of the patients dying from UESL. Surgical approach in this situation is tailored to the tumor type and extension; staged approaches are reported: either removal of cardiac extension under cardiopulmonary bypass followed later by hepatic tumor resection, or the opposite, hepatic tumor resection first, followed by removal of cardiac extension under cardiopulmonary bypass[29,30].

Table 2. PRETEXT, COG and IRS liver tumor staging systems

Preoperative tumor rupture

Preoperative tumor rupture raises questions about recurrence as it can lead to inappropriate primary tumor resection[9]. Spontaneous tumor rupture was reported to occur in 6.5% of the patients[31]. The emergency treatment in case of spontaneous or post biopsy tumor rupture is arterial embolization of the feeding artery[32,33]. Recent data supports that secondary tumor resection with preoperative chemotherapy is more successful than primary resection without an effective adjuvant regimen in this particular setting[31].

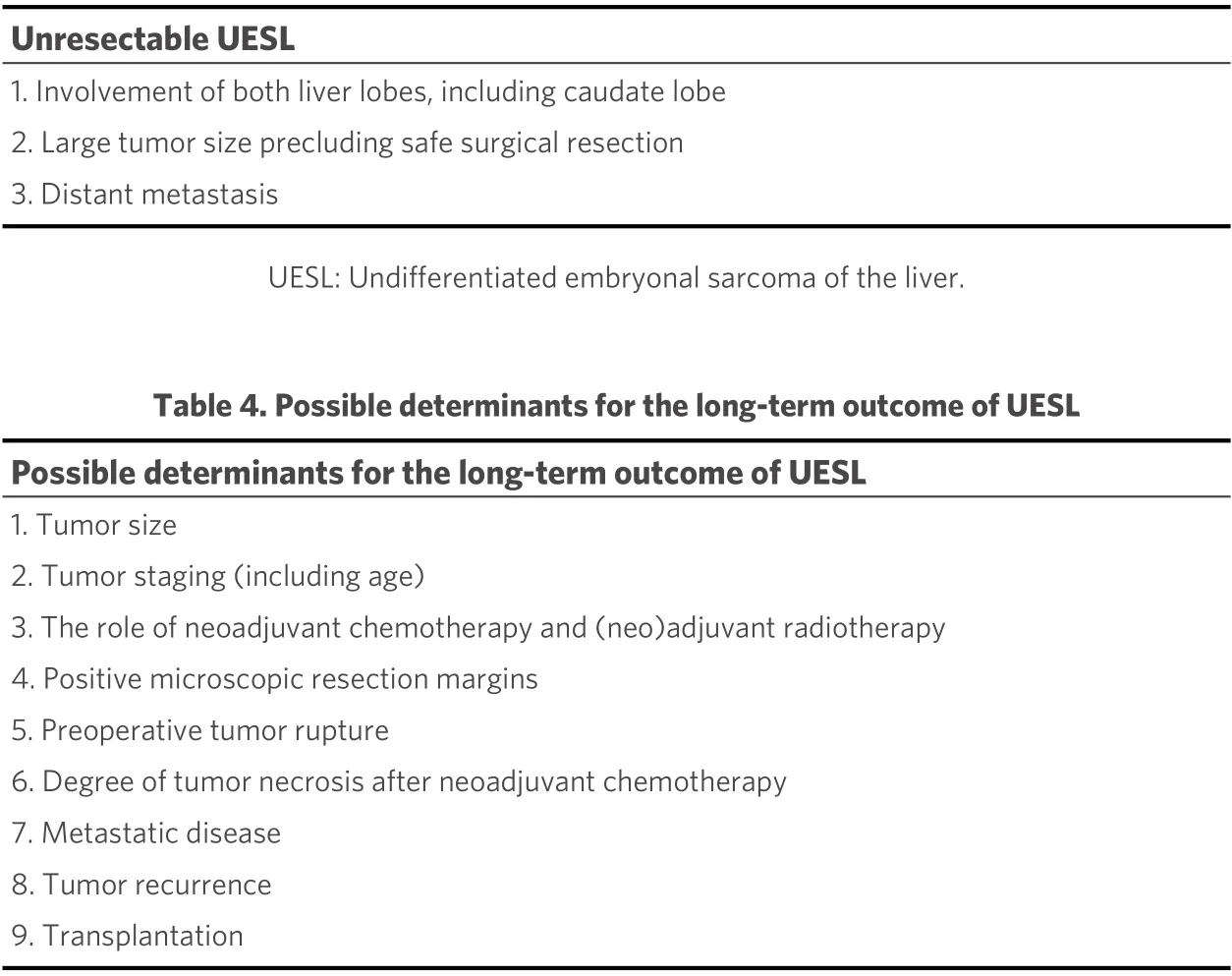

Unresectable UESL and liver transplantation

In the context of unresectable tumors [Table 3][20], two strategies might be adopted and can be defended,aggressive resections versus liver transplantation as an alternative[20]. A recent review reported on twelve liver transplanted patients within the United Network for Organ Sharing, with only one needing a retransplantation and another one succumbing the disease[14]. Individual case reports are supporting this increasingly accepted indication[10,14,34-37]. Overall, transplantation seems to concern 10% of UESL patients[12].

COMPLICATIONS AFTER UESL SURGICAL TREATMENT

Complications after surgical management of UESL are rarely reported, but exist as in all liver surgery.Typically, biliary complications were the most frequently reported complication. In a series of seven patients, bile leaks occurred in 28% (2/7) of patients, with one resolving spontaneously and one needing an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with biliary drainage[29]. Biloma rate was higher in a fivepatient case series, in which two (right lobectomy) patients required a drain placement, and one (left lobectomy) a cholecystectomy with bile duct ligation; this last patient also had a cavernomatous transformation of the portal vein[38]. A bile duct injury after a right hepatectomy needed a redo surgery with a Roux-en-Y loop[9].

Table 3. Reported criteria for unresectable UESL

Liver failure was described in a three-patient case series causing one patient’s death, but data concerning tumor location and surgical excision is scarce[39]. One post-resection liver failure needed a rescue liver transplantation in another series[9].

One in 17 patients was reported to die after a right lobectomy in an early report of 2002, due to surgical complications[22].

SURVIVAL

Five-year survival rate was less than 40% in the early 1980’s[11], with current survival rates higher than 80%[11,14,28]. It seems that diagnosis errors with inadequate surgical management lead to lower survival rates[40], again, supporting the evidence that more generally accepted standardized protocols are needed.

Studies focus mainly on the chemotherapy regimens when making correlations with survival rates. The role of other determinants for the long-term outcome summarized in Table 4 needs further clarifications[9,12,41].

CONCLUSIONS

Over the last decades, the outcome of pediatric UESL has improved. To allow for optimal management of UESL, and thus for accurate outcome analysis, systematic, preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy should be further defined, as compared to upfront surgery. A new risk stratification grouping system for UESL including the PRETEXT staging, age of patient, and size of the mass might be considered in a prospective study. Further, the role of positive microscopic margins needs to be defined.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study, performed data analysis and interpretation, finally approved the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work: Calinescu AM, Wildhaber BE, Guérin F

Performed the draft: Calinescu AM, Wildhaber BE

Critical revision of the intellectual content: Wildhaber BE, Guérin F

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

? The Author(s) 2021.

- Hepatoma Research的其它文章

- GENERAL INFORMATION

- AUTHOR INSTRUCTIONS

- The prognostic evaluation of marginal positive resection in hepatoblastoma: Japanese experience

- Role of CD4+ T-cells in the pathology of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and related diseases

- Defining the role of laparoscopic liver resection in elderly HCC patients: a propensity score matched analysis

- Contribution of C3G and other GEFs to liver cancer development and progression