The International Profile of Chinese Visiting Scholars in the UK:Improvement Needed in Linguistic,Cultural, and Academic Confidence

Zhang Rui

Xi’an International Studies University

Abstract: This study used Chinese visiting scholars in the UK as a sample,discussed Chinese visiting scholars’ cross-cultural adaptation from the perspectives of linguistic confidence, cultural confidence and academic confidence, analyzed the correlation among the three types of confidence,and then proposed the concept of establishing a positive international profile of Chinese visiting scholars. It was recommended that Chinese visiting scholars should make more improvements in their cross-cultural adaptation. They should become the representative of China’s international image, and play a more active role in further internationalizing of Chinese higher education.

Keywords: Chinese visiting scholars, international profile, linguistic confidence, cultural confidence, academic confidence

With the strategic development of higher education internationalization in China, Chinese higher education is moving forward even more rapidly and steadily. As the internationalization of faculty is the core of Chinese higher education internationalization (Chen & Liu,2011), more and more Chinese scholars, mainly university teachers, have been provided with chances to study and visit abroad, especially in well-developed Western countries. Since the establishment of the China Scholarship Council (CSC) in 1996, an increasing number of Chinese scholars have been selected and sent abroad annually for academic exchanges (CSC, 2010). In 2018 alone a total of 27,392 people were sponsored by CSC to study abroad, among whom 70 percent were senior scholars,visiting scholars, post-doctoral scholars or doctoral students, and 77 percent of them went to the US,the UK, Canada, Germany, France, Russia, Australia, Japan, etc. (Sheng, 2019). Given the number of scholars sponsored by other funding agencies and institutions and self-funded scholars, there are a great number of Chinese scholars going to different countries all over the world every year.

Returning scholars have exerted significant influence on the reform of traditional disciplines, the establishment of new disciplines, and the improvement of the quality of teaching and personnel training. They have contributed to the remarkable progress of domestic scientific research, further narrowing the gap between the research level in China and the international level. While spreading Chinese culture to the world through their academic exchanges, they have also brought about economic benefits for China by undertaking international programs and the applications of their research achievements (CSC, 2010).

Previous Studies on Visiting Scholar Mechanisms

As a result of the rapid development of the visiting scholar programs in China, both accomplishments and problems related to the mechanisms involved have been observed.Several studies discussed the merits, problems and barriers reflected in the cooperative process between Chinese visiting scholars and the host universities. By using the case of Chinese visiting scholars at a university in Canada, Miller and Blachford (2012) explored how fostering collaboration among Chinese visiting scholars, the host university and the community enhanced internationalization, and put forward a partnership model connecting the interests of the university, international visiting scholars, and the local community by emphasizing mutual benefit, shared learning, cross cultural understanding, collaboration and sustainability.Xue et al. (2015) studied Chinese visiting scholars’ academic socialization in some universities in the US, and found that Chinese scholars employed strategies such as motivation, social networking development, academic recognition, goal orientation, and community involvement;meanwhile, their studies analyzed the reasons for Chinese visiting scholars’ dilemmas like marginalization, time constraints, and external critiques. Li Y. X. and Li Z. S. (2018) discussed the reasons and motives for Canadian universities’ acceptance of international academic visitors, and the challenging problems in their cooperation, gains from their cooperation and suggestions for future cooperation. According to Liu and Jiang (2015), before 2015, Chinese literature on Chinese faculty studying abroad mainly focused on policies and management issues. The two researchers found that there were few empirical studies on the experiences and outcomes of the returning Chinese visiting scholars, so they did a systematic investigation into the challenges facing Chinese visiting scholars and the gains made by them and came to the conclusion that visiting scholar programs should be viewed as a crucial approach to the professional development of faculty and be incorporated into a comprehensive package for Chinese university faculty (Liu & Jiang, 2015). Since then, more researchers have conducted various surveys among Chinese visiting scholars, mainly about their gains from the overseas experience. Jiang and Liu (2015) pointed out in another paper that Chinese visiting scholars had achieved considerable internal and external outcomes through their overseas experiences in terms of changes in values, improvement in teaching and research practices, and enhancement of international academic cooperation. Similar results can be found in another paper which demonstrated that overseas faculty training could bring direct and indirect benefits in faculty attitude, teaching, research, and service (Ma & Wen, 2016). Huang et al. (2016) proved that there was a significant positive correlation among the motivation, procedures and effects of the overseas visiting scholar programs, and suggested China should enhance the correct motivation,strictly monitor the applications, expand the scope of cooperation, and continue to increase the investment. Zhao et al. (2018) discussed and analyzed visiting scholars’ practical obstacles:Preparations before leaving the country were complicated and time-consuming; the external drive to visit foreign countries was too strong while internal motivation was insufficient; the level of enthusiasm for academic cooperation between Chinese scholars and their foreign mentors differed; procedural supervision did not show substantive meaning; social and cultural differences negatively affected endogenous academic pursuits; diffusion mechanisms after returning from visits were not effective.

While most of the studies mentioned above concluded that Chinese visiting scholars had indeed achieved beneficial outcomes from their academic visits and studies abroad, some also pointed out that Chinese scholars’ lack of English proficiency and cross-cultural knowledge hindered the cooperation between them and their foreign mentors (Li & Li, 2018; Liu &Jiang, 2015; Jiang & Liu, 2015; Xue et al., 2015). Few studies discussed Chinese scholars’ own reflections on their academically adaptive barriers induced by an insufficient reservoir of language and culture, their mentors’ feedback on the impact of their adaptive barriers on the academic cooperation, and how they could get rid of this dilemma and smooth the academic cooperation between them and their mentors in a context of cross-cultural communications.Although Liu C. (2016) discussed the profile of Chinese scholars as the interpreter of China’s international image, the conveyor of Chinese culture, and the victim of the so-called “China threat” theory, the profile was drawn from the perspective of international media, rather than in a cross-cultural context closely related to Chinese visiting scholars’ everyday overseas experience. Other than his discussion, few studies have drawn an overall international profile for Chinese visiting scholars in terms of their linguistic, cultural and academic capabilities in the host countries, through which scholars and professors in other countries could learn more about Chinese visiting scholars and thus improve mutual understanding and further cooperation between Chinese scholars and their foreign mentors, as well as the host universities.

Kim’s Theory as the Theoretical Framework

Chinese visiting scholars’ communication and adaptation in the host countries are a multidimensional procedure. As a result, it is necessary to apply a comprehensive and integrative theory to investigate their overseas experiences. Compared with previous theorists and researchers involved in intercultural communication and adaptation, Young Yun Kim used open-systems theory as an organizing framework and proposed a comprehensive theory of cross-cultural communication and adaptation based on a wide range of existing concepts, models, and research data derived from different disciplines (Qian, 2013). The theory incorporated an individual’s communicative capability in accordance with the host communication system and his or her psychological and social interactions with the host environment. Kim went beyond the traditional linear-reductionist conceptions of adaptation and focused on its interactive, multifaceted, and evolving nature. Kim’s theory, including three open-systems assumptions, three boundary conditions, 10 axioms, and 21 theorems, has so far been the most broad-based theoretical account of cross-cultural adaptation; it not only brought many conceptions together but also clarified the interrelationships among different conceptions.Kim’s comprehensive theoretical framework can be applied to research into both long-term and short-term adaptation processes (Qian, 2013).

According to Kim’s theory of communication and cross-cultural adaptation (2001, p. 5),once strangers entered a new culture, the cross-cultural adaptation process started and the strangers’ habitual patterns of cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses experienced adaptive changes. Through the process, the strangers increased their proficiency in selfexpression and fulfilled of their various social needs.

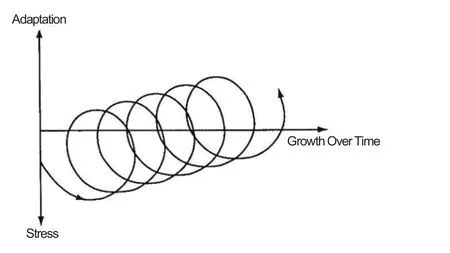

Kim proposed a process model to present the dynamic adaptation process of strangers(see Figure 1). She explained that stress,adaptation, and growth highlighted the core of strangers’ cross-cultural experiences in a new environment, and that the three were closely correlated.Additionally, the stress-adaptation-growth dynamic worked not in a smooth, linear progression, but in a cyclic and continual“draw-back-to-leap” pattern, analogous to the movement of a wheel. Strangers responded to each stressful experience by“drawing back,” which in turn activated adaptative energy to help them reorganize themselves and “l(fā)eap forward” (Kim, 2001, pp. 3-4).

Figure 1 The stress-adaptation-growth dynamic: A process model (Kim, 2001, p. 57)

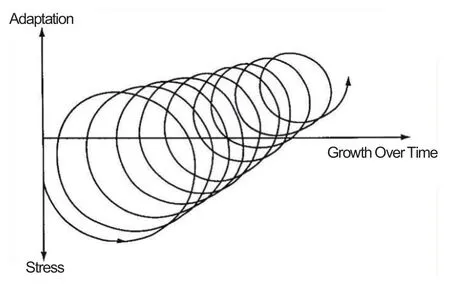

Kim further explained that over a long period of time, when strangers experienced certain internal changes, the fluctuations of stress and adaptation were likely to become less severe, resulting in internal calmness,indicating the strangers’ gradual adaptation to a new environment. As a result, the depiction of the stress-adaptation-growth dynamic could be modified to reflect a diminishing severity in its fluctuation over time (2001, p. 59) (see Figure 2).Kim added that not all individuals were equally successful in better adaptation. The degree of adaptation was dependent on an individual’s existing inner resources (2001, pp. 59-60).

Figure 2 Diminishing stress-adaptation-growth fluctuation over time(Kim, 2001, p. 59)

Once Chinese visiting scholars enter a cross-cultural environment, they will encounter problems caused by their lack of language proficiency and cross-cultural knowledge, as indicated in previous research on Chinese visiting scholars. Kim’s focus on the importance of language and culture in the process of cross-cultural adaptation can be employed to explain Chinese visiting scholars’ underperformance in a foreign culture. By applying Kim’s theory of communication and adaptation as its theoretical basis, this study aims to determine how much Chinese visiting scholars’ inadequate language proficiency and insufficient cross-cultural knowledge influence their academic adaptation in a foreign university, and how they and their mentors perceive the communicative barriers caused by language and culture-related factors,as well as what they (should) do to improve their linguistic confidence, cultural confidence,and academic confidence. At the end of the study, an international profile of Chinese visiting scholars in the UK will be drawn based on previous discussions and analyses; also, it is proposed that all Chinese visiting scholars should bear in mind the concept of, and strive for the establishment of a positive international profile for Chinese scholars.

Research Methods

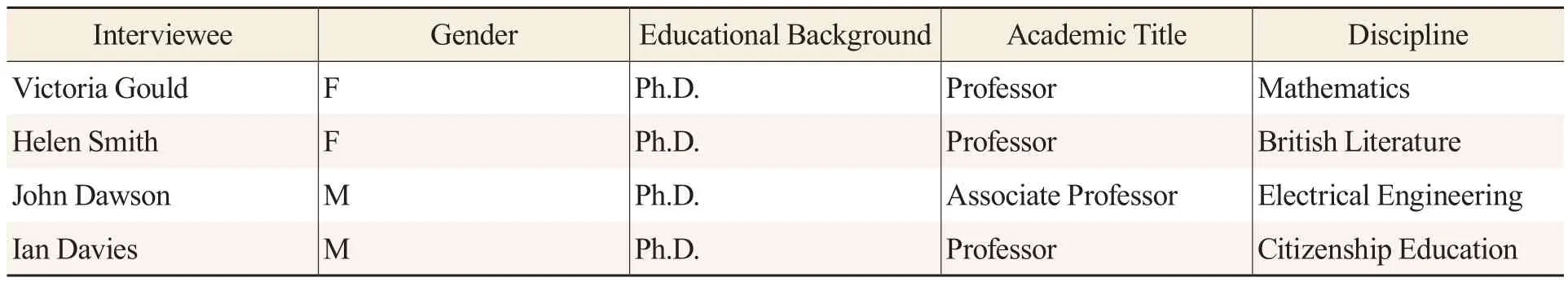

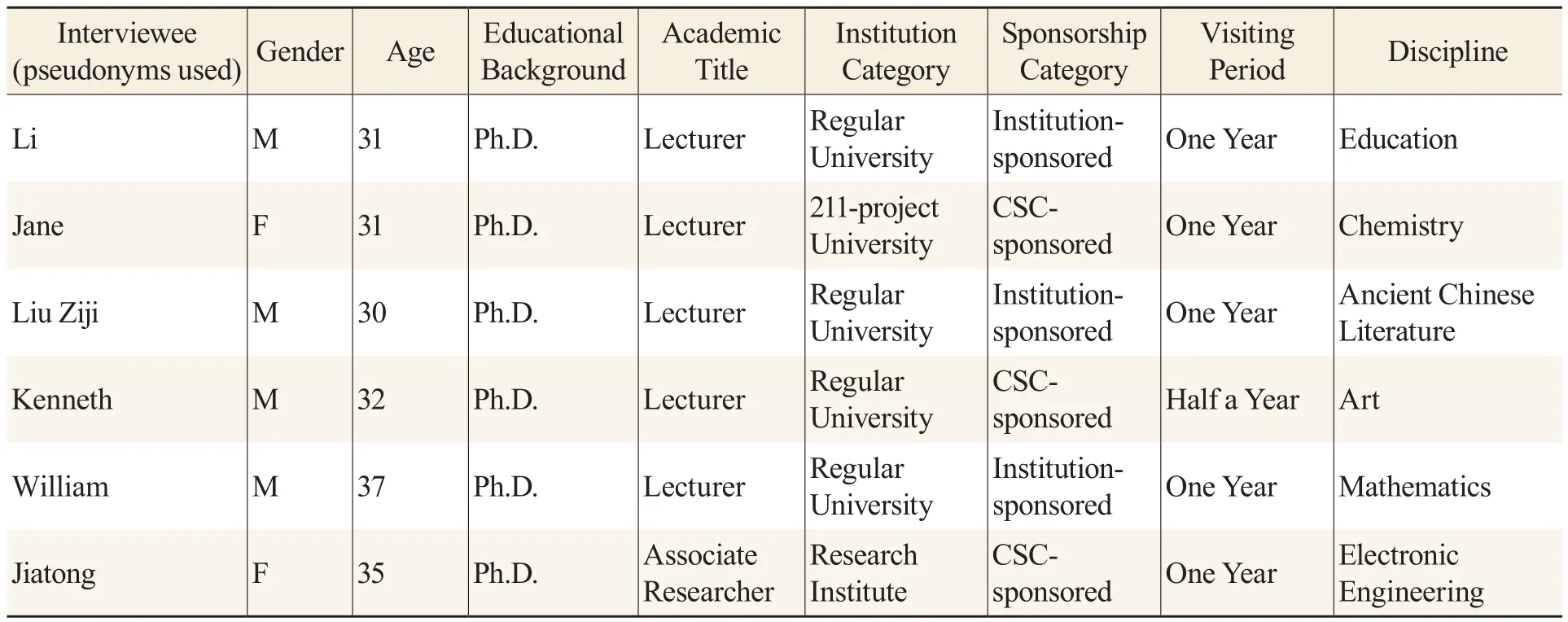

A combination of quantitative research and qualitative research was employed in this study.Chinese visiting scholars who visited academic institutions in the UK were exclusively selected as the target population. With Questionnaire Star, a software tool for questionnaires widely used in China, a questionnaire survey was conducted among Chinese visiting scholars, and a total of 120 questionnaires were collected using WeChat and QQ as the media for investigation;excluding the questionnaires from non-visiting scholars, 106 of the 120 questionnaires were valid. In order to obtain more accurate and reliable data, another small-scale questionnaire survey was conducted among Chinese visiting scholars who were visiting or had visited the University of York, and a total of 30 questionnaires were collected; excluding the questionnaires from non-visiting scholars, 27 of the 30 questionnaires were valid; also, face-to-face interviews were conducted with four professors at the University of York (Table 1), and a WeChat interview was conducted with six Chinese visiting scholars during their academic visits at the University of York (Table 2).

Table 1 Interviewees’ Profiles (professors at UoY)

Table 2 Interviewees’ Profiles (Chinese visiting scholars)

The data from the two questionnaires were analyzed and used to create a general outline of Chinese visiting scholars’ cross-cultural adaptation in British academic institutions. The data collected from the semi-structured interviews with the four professors at the University of York (UoY) and the six Chinese visiting scholars helped to investigate the interactions and communication between Chinese scholars and their mentors more deeply. The essential features of Chinese visiting scholars’ cross-cultural adaptation were derived and refined from a comprehensive analysis of the data collected from both the questionnaires and the interviews,and thus a brief international profile of Chinese visiting scholars in the UK was established.Suggestions for improving Chinese visiting scholars’ general international profile were provided after a systematic analysis of all data.

Chinese Visiting Scholars’ Linguistic, Cultural and Academic Confidence

English Proficiency and Relevant Problems

As proposed by Richard Clément, linguistic self-confidence is a powerful mediating process in a multicultural setting that affects a person’s motivation to use the language of another speech community (Wong, 2015).

As a result of the typical way of English teaching in China, which focuses mainly on students’grammar, reading and writing, but pays less attention to listening and speaking, most English learners in China are good at English reading and writing, but poor in listening and speaking. To a great extent, English is no longer considered as a communication tool but viewed as a survival skill for job-hunting or promotion in China (Ye, 2008). The older people are, the more obvious this phenomenon is among them. Since Chinese visiting scholars are mainly aged from 30 to 45, they are a generation deeply influenced by the typical Chinese way of English teaching.In the questionnaire survey, 15 of the 106 Chinese scholars were English majors, marked by a comparatively higher level of linguistic confidence. By contrast, the situation among the 91 non-English majors was a different picture: Many of them (57.14 percent of the 91) admitted that their listening and speaking were not as good as their reading and writing. The situation was more or less the same among the 27 Chinese visiting scholars who visited the University of York. Among the six Chinese scholars involved in the WeChat interview, most were not confident with their listening and speaking, but had more confidence in their reading and writing.

On the part of their mentors, the situation was not overly optimistic, either. According to Victoria Gould, many people in China have been taught to read and write in English quite well.However, it can be hard for some of her Chinese visitors to understand the spoken word. It might be the way in which native speakers speak English; presumably the tone and the way of speaking are so different from what people learn in China.

John Dawson mentioned that quite often his Chinese research visitors did not understand him while he did not always understand them either. Ian Davies summarized from his communication with several Chinese scholars he had hosted that the older the scholars,generally the more difficult it was to communicate with them.

Obviously, Chinese visiting scholars’ inadequate English proficiency, especially their listening and speaking, hinders their daily cross-cultural communication in the UK, and the problem seems even more serious when they participate in academic communication and exchanges. According to Vitoria Gould, a person’s language proficiency is crucial in academic exchanges.

Since academic activities are mainly conducted in the form of lectures and seminars, it is a great challenge for most Chinese visiting scholars to fully understand and then articulate their personal viewpoints; even the English majors in the questionnaire survey were not very confident with their English in academic exchanges. As was pointed out in one study on the internationalization of college teachers in China, the overall level of Chinese college teachers’ English proficiency was not very high, and from the perspective of scientific and academic exchanges, this problem would lead to unbalanced communication and collaboration between Chinese scholars and Western scholars, making it difficult to realize academic internationalization in China’s higher education (Chen & Liu, 2011). From the questionnaire surveys, nearly half of the Chinese visiting scholars (48.11 percent of 106; 44.44 percent of 27)agreed that their lack of linguistic confidence negatively influenced their academic confidence.

According to Kim’s cross-cultural adaptation theory, host language competence is the primary agent of socialization with which individuals can approach the host culture and pursue personal and social goals (Kim, 2001). For most Chinese visiting scholars, however, due to insufficient linguistic competence, they were unable to get involved in a meaningful way in a cross-cultural academic environment; thus, it was little wonder that most Chinese visiting scholars encountered obstacles such as marginalization and did not have a sense of belonging during their academic visit in a foreign country (Xue et al., 2015).

Strategies for Improving English Proficiency

The use of positive intercultural communication strategies will serve to minimize the level of anxiety and enhance linguistic self-confidence (Wong, 2015). It was only through extensive and continuous exposure to, and participation in host social processes that individuals were able to develop a deeper understanding of the pragmatics of the host language (Kim, 2001). In the questionnaire survey among the 106 Chinese scholars, more than half (52.83 percent) had a relatively strong desire to improve their English and practiced on certain occasions, and 15.09 percent had a very strong desire to improve their English and practiced whenever they could.All of the six interviewees said their English had improved noticeably through continuous academic exchanges and by communicating more with native speakers in their daily lives.

The greater the preparedness for change, the greater the host communication competence(Kim, 2001); the greater the adaptive personality, the greater the host interpersonal and mass communications (Kim, 2001). Despite the fact that inadequate English capacity negatively impacted Chinese visiting scholars’ academic interactions with their mentors, they were always making great efforts to improve their English to smooth the intercultural communication.During their time in the UK, Chinese visiting scholars could always take advantage of the language environment to immerse themselves in English so as to improve their linguistic confidence and become more proficient in their cross-cultural adaptation.

Cultural Knowledge Reserve and Relevant Problems

Confidence in native culture means a country or a nation fully confirms the value of their own culture and has a firm faith in the vitality of their own culture (Yun, 2011). Since cultural confidence primarily concerns proper attitudes towards culture and must be based on cultural consciousness (Xu & Chen, 2018), it is reasonable to conclude that confidence in a foreign culture should include a good command of corresponding knowledge and proper attitudes towards the foreign culture.

It is preferable to discuss Chinese scholars’ confidence in both Chinese culture and Western culture as both factors have certain influence on Chinese scholars’ cross-cultural communication and adaptation. In the questionnaire survey of the 106 Chinese scholars, 36.79 percent said their knowledge of traditional Chinese culture was not adequate, and more than half thought they knew about traditional Chinese culture comparatively well. As for their cross-cultural knowledge, while 33.96 percent of the scholars were relatively confident with their cross-cultural knowledge, more than half of the scholars thought they only had a limited amount of cross-cultural knowledge. Once cultural differences emerged, 26.42 percent of the 106 scholars said they would respect Western culture and admit the existence of cultural differences but would not accept Western culture voluntarily; while 73.58 percent thought they would also respect Western culture and could fully understand the cultural differences,preferring to selectively accept some Western culture.

From the data above, it was not difficult to summarize that Chinese scholars’ cultural knowledge was not strong in general, whether of Chinese culture or Western culture; luckily,a great majority held an open mind towards Western culture and cultural differences. What is more, cultural differences indeed hindered the communication and interactions between Chinese visiting scholars and their mentors. For instance, due to a lack of cross-cultural knowledge of the two sides, the academic communication between John Dawson and his Chinese visitors sometimes really puzzled him, especially when he discovered that the visitors did not quite understand his points but still kept silent without asking him to explain in detail, let alone challenging his academic ideas. When the six Chinese visiting scholars involved in the interview were asked to comment on the phenomenon above, nearly all of them attributed it to the differences between Western culture and Chinese culture, with the latter advocating harmony and integration and paying great attention to holistic appeals such as unity, moderation, kind-heartedness, justice and harmony (Xu & Chen, 2018). Li (pseudonym)and William (pseudonym) said when they were in such a situation, they would first think over their mentors’ views very carefully and deeply; Li thought he would not challenge his mentors because in his mind they were very authoritative in his research field, and William said he would not challenge his mentor unless he was absolutely confident with his own idea.

Kim (2001) summarized that cultural understanding helped individuals to share the native people’s shared memory, to interpret underlying meanings, and to see how and why the native people communicated in the ways they did. From the instance discussed above, it was clear that most Chinese visiting scholars did not grasp enough cross-cultural knowledge; the dilemma was that their traditional Chinese ways of doing things sometimes confused their mentors, but the Chinese scholars themselves did not realize this. Thus, it is quite reasonable to conclude that Chinese visiting scholars should command more cross-cultural knowledge in order to adapt better in a foreign country and achieve more academic outcomes. However, few people seemed to realize the importance of knowing more about Chinese culture and publicizing it when necessary. China has a long history characterized by one of the most ancient and unique civilizations in the world. Thanks to its rapid socio-economic development, China nowadays attracts more and more attention from the global community. Chinese visiting scholars are mainly the elite in their academic fields and the pillars of the nation. When they are sent abroad to study and work as academic visitors, they will enter a cross-cultural environment; to promote their cross-cultural adaptation and enhance the transmission of Chinese culture, they should know a great deal about both the host culture and traditional Chinese culture (Jiang &Zeng, 2012). Only in this way can they promote knowledge about China and Chinese people to other cultures; only when others know more about China and Chinese people, can better mutual understanding and smoother cross-cultural communication be realized and enhanced.

Nevertheless, the fact that cultural barriers to some extent block smooth academic exchanges between Chinese visiting scholars and their mentors cannot be ignored. The necessity that Chinese scholars should both increase their cross-cultural knowledge and learn more about traditional Chinese culture cannot be overemphasized. Otherwise, as it was stated in a previous study, not only did communication difficulties and breakdowns restrict Chinese scholars’ involvement in academic socialization, academic cultural differences also limited their academic learning outcomes (Xue et al., 2015).

Strategies for Improving Cross-cultural Communication

Culture and language are inseparable. The acquisition of cultural knowledge can not only stimulate one’s enthusiasm in language learning, but also help promote deep understandings of cross-cultural communication. Thus, it is necessary to make comparisons between one’s native culture and the host culture, and the purpose of doing so is not to decide which one is superior, but to identify the essential differences between them, thus achieving a profounder comprehension of the essence of each culture (Chen, 2006). Through this purposeful comparison between the native culture and the host culture, one would find it easier to adjust in a cross-cultural environment. The problem for most Chinese visiting scholars is that even though they are familiar with Chinese culture, it is difficult for them to express Chinese culture in English (Jiang & Zeng, 2012). Therefore, the key to this problem is that Chinese scholars should learn more of the English expression of Chinese culture while they are becoming more familiar with Western culture.

In addition, the establishment of cultural confidence is based on certain qualities like cultural tolerance, adaptability, and reflective capacity (Xu & Chen, 2018). To achieve better cross-cultural adaptation, one of the prerequisites is that people should establish a good sense of intercultural awareness, not feeling inferior or arrogant when faced with cultural differences,but keeping an open mind to cultural differences and seeking common ground while reserving differences (Shen, 2019). Chinese visiting scholars should keep appropriate attitudes towards foreign cultures and reflect frequently and deeply on cultural differences.

Academic Adaptation

The fundamental aim of the visiting scholar programs in China is to promote national modernization and internationalization, and a large-scale study conducted by Zweig et al.showed that the returnees were significant contributors to economic growth, technology,and skill transfer (Miller & Blachford, 2012). Meanwhile, a good number of studies in recent years also indicated that returning Chinese scholars gained both external and internal benefits from their overseas experience (Jiang & Liu, 2015; Ma & Wen, 2016; Huang et al.,2016). As discussed previously, although Chinese scholars’ inadequate language proficiency and insufficient cultural knowledge exerted a negative impact on their academic adaptation,most Chinese scholars had acquired much from their academic visits abroad. This trend was consistent with Kim’s cross-cultural adaptation theory, which held that an individual’s crosscultural experiences were characterized by stress, adaptation, and growth and that the stressadaptation-growth dynamic did not function in a smooth, linear progression, but in a cyclic and continual “draw-back-to-leap” pattern (Kim, 2001). In spite of the fluctuations in Chinese visiting scholars’ cross-cultural adaptation, they were indeed heading forward and making more achievements.

Cross-cultural Academic Exchange and Adaptation

The academic communication between Chinese scholars and their mentors could be categorized into the following types: 42.45 percent of the 106 Chinese scholars conducted independent research; 28.3 percent could get academic supervision from their mentors when necessary; 15.09 percent cooperated with their mentors to carry out research; a small percentage(5.66 percent) could be supervised by their mentors throughout the academic visit and deemed that the mentor played a significant role in the entire research process; very few complained that they needed supervision from their mentors but were always ignored.

In the questionnaire survey, when asked to compare the academic atmosphere of their domestic institution in China with that of the host institution in the UK, most Chinese visiting scholars (89.63 percent of 106) were inclined to say that the host institution was marked by a better and stronger academic atmosphere. The six interviewees used modifiers such as “free”,“clear”, “l(fā)ively”, “strict”, “rigorous” and “humanistic” to describe the academic atmosphere at the University of York, and they thought this kind of academic atmosphere helped faculty fully concentrate on academic research. Most Chinese scholars thought highly of their mentors’academic capability. All the six Chinese scholars having a mentor at the University of York were highly impressed by their mentors’ rigorous academic attitude and extraordinary academic capability.

When it came to their self-reported academic capability, 52.83 percent of the 106 Chinese scholars thought their capability was of a medium level; 40.57 percent thought their academic capability was relatively good and could conduct certain research; only 6.6 percent thought their academic capability was extraordinary and were able to conduct profound and complicated research. Clearly, most Chinese visiting scholars still had great potential for further academic improvement. This feature was meanwhile a striking reflection of the general profile of Chinese visiting scholars: Among the 106 participants, 70.75 percent were associate professors and 20.75 percent were lecturers, which indicated that they were in the rising phase of their academic career. Victoria Gould commented on Chinese visiting scholars’ academic capability by using the word “mixed”. The five scholars she hosted had been of a broad range of mathematical preparation and background.

In a cross-cultural context, it would be unavoidable for Chinese scholars to make comparisons between their foreign peers’ academic capability and their own academic capability; they should be aware that many types of academic confidence are negatively influenced by people making upwards comparisons, and that low self-confidence and illusory inferiority can result in slower progress (Pulford et al., 2018). Therefore, Chinese visiting scholars should hold an objective view of their individual academic capability and employ active strategies to enhance their academic confidence. The more academic confidence they develop, the more they will be motivated to pursue greater academic achievements. When they are immersed in an environment with a stronger academic atmosphere marked by innovation and vitality, and with more rigorous mentors who possess better academic capability and abundant achievements, they will be assimilated academically.

After having been immersed in a good academic environment and impressed by their mentors’ extraordinary academic capability, Chinese visiting scholars would be expected to build more academic confidence and better academic capability. Academic confidence is based on academic capability. Academic confidence is not only a question of how capable a scholar is in academic research. More exactly, it refers to an academic group’s positive attitudes towards their own values and capabilities, and themselves as academic scholars (Cao, 2019). In a cross-cultural context, the exhibition of academic confidence in academic exchanges can be very complicated as an individual scholar’s language proficiency plays a role in the exhibition process. Even though a scholar is highly confident in his/her academic capability in China, he/she would feel greatly discouraged and frustrated if limited language proficiency restricts the expression of their academic capability in the host university. What makes things worse is that according to relevant management regulations in some Chinese universities, to be promoted as associate professor or professor, one should have overseas study experience. As a result, many scholars chose to go abroad because of external stimuli (Zhao et al., 2018), despite the fact that some scholars’ English was not good enough or even disadvantageous to their academic capability in a cross-cultural academic environment. This phenomenon certainly had a negative impact on the exhibition of Chinese visiting scholars’ general academic confidence on the international stage. In one word, in a cross-cultural context, linguistic capability becomes the medium of the exhibition of academic capability. The higher one’s linguistic capability is, the easier it would be for one to show more academic confidence, and vice versa.

Chinese Visiting Scholars’ Reflection on Their Academic Visit in the UK.

Nearly all the participants in this study mentioned that they had achieved prominent outcomes in different aspects and on different levels. First of all, despite the fact that most of them were non-English majors and their English was not very good, most scholars found that their listening and speaking had become better as a result of practice during their academic stay in the UK. In this modern society characterized by globalization and internationalization,it is a definite trend for academics in countries where English was used as a second language to publish papers in the process of academic internationalization (Xu, 2014). For example, to build a world-class university, many universities in China require the faculty to publish more papers in international journals (Luo, 2014). Also, faculty’s overall English proficiency is crucial for bilingual teaching in most Chinese universities in an effort to promote the development of internationalization (Liang, 2009; Li, 2011). As the driving force in China’s higher education internationalization, university teachers, including most Chinese visiting scholars, are much clearer about the importance of English proficiency. Meanwhile, more Chinese visiting scholars are starting to realize the necessity of developing cross-cultural competence.

Chinese visiting scholars’ academic involvement in the host academic department and university varied in terms of disciplines, the degree of independence, and their mentors’requirements. Scholars spent their time in the UK in different ways and gained different experiences from their academic visits. Certainly, the overseas experience influenced them to a great extent. According to this survey, the outcomes that Chinese visiting scholars achieved could be summarized into the following categories: international perspectives, new academic visions, rigorous academic attitudes, distinct research models, and management approaches.Also, Chinese scholars’ living style, mental state and vision were different from those before.They obtained much from their academic stay in the UK, something tangible, and something intangible.

Just as was shown in Kim’s modified Stress-Adaptation-Growth Dynamic (see Figure 2)(Kim, 2001), over a certain period of time, as Chinese scholars went through a progression of internal change, the fluctuations of stress and adaptation were likely to become less intense or severe, leading to an overall “calming” of the scholars’ internal conditions. There were indeed ups and downs in Chinese visiting scholars’ cross-cultural adaptation due to linguistic and cultural problems, but they adapted to the cross-cultural environment and moved forward holistically.

The Establishment of a Positive International Profile of Chinese Visiting Scholars

Owing to their overseas academic experience, most of the Chinese visiting scholars became the backbone in their domestic institutions and had great potential for development. From previous studies, both compliment and criticism could be found regarding the profile of Chinese visiting scholars. After all, most scholars worked very hard and achieved a lot during their overseas experience. They not only made great progress in their own career development, but also brought new ideologies, perceptions and thinking modes back to their domestic institutions.In the questionnaire survey, when it came to the concept of “establishing a positive international profile of Chinese visiting scholars,” 34.91 percent of them always paid a great deal of attention to their conduct and manners, and always remembered to establish a positive international profile of Chinese visiting scholars; 50.94 percent of the 106 Chinese scholars said that they paid some attention to their conduct and manners, trying to establish a positive international profile of Chinese visiting scholars; 9.43 percent paid attention to their own conduct and behaviors but did not sense the existence of this concept; 2.83 percent did not relate the concept to themselves; very few (1.89 percent) were only concerned about themselves. It is true that one visiting scholar cannot represent all Chinese scholars, but if many individual scholars do not behave like a scholar or do not do what a scholar should do, that would damage the international profile of Chinese scholars as a whole.

When asked about their impression of Chinese visiting scholars, the four professors at the University of York thought highly of Chinese scholars and were impressed by their diligence,devotion to work, courtesy, and easygoingness. Although being confused quite often by the cultural differences between himself and his Chinese research visitors and scholars, John Dawson said he enjoyed working with them. According to Helen Smith, Chinese scholars were very thoughtful, courteous, serious, and very keen to make the most of their time in the UK. That was her general impression. Gould said her Chinese visiting scholars had very good work ethics, who worked very hard and were always nice and studious.

Ian Davies made a relatively comprehensive comment on Chinese scholars and contributed some advice for improvement in Chinese scholars’ international profile. He said that it was very easy to be with Chinese people because they were very quiet and respectful. But that easiness in many ways might suggest or reveal a lack of confidence. It was quite a subtle process of maintaining the very constructive and respectful approach which was wonderful. At the same time, they should be more proactive and show more initiative and critique.

As a result of both the influence of traditional Chinese culture and the fact that English was their second language, most Chinese visiting scholars were unable to fully show their academic capability and confidence, which was a hinderance for the establishment of a positive international profile of Chinese visiting scholars in general. 55.66 percent of the 106 participants in the questionnaire survey agreed that linguistic confidence and cultural confidence could enhance academic confidence, but 66.98 percent found that their low level of linguistic confidence negatively influenced their academic confidence, and 24.53 percent found that their low level of cultural confidence negatively influenced their academic confidence.Linguistic confidence and cultural confidence cannot determine one’s academic confidence, but can affect the exhibition of one’s academic confidence. Moreover, as Ian Davies commented,Chinese scholars should be more proactive, both academically and culturally. To be specific,it is not enough for them to know more about Western culture and learn how to adjust to the Western environment; they should be clear that nowadays more and more people in the West also want to know more about China and Chinese culture. If scholars become more proactive,they will create more chances to publicize Chinese culture, so that intercultural communication would become easier and smoother.

Chinese scholars should also be more innovative. From the survey, more than half (57.55 percent) of the 106 scholars said that they were relatively innovative but could not put this innovation into practice. During intercultural academic communication, both sides would like to obtain something innovative, something enlightening, and something that they have not seen or experienced. It would not be a sensible choice for one to stick to the cliché, reporting what they have already seen and repeating what have been said to them. Just as Ian Davies said, some visiting scholars simply observed what was going on in the department, and wrote reports when they are back. Thus, together with improved language proficiency and an enriched cultural reservoir, innovation, collaborative spirit and international vision can never be overemphasized in the establishment of a positive international profile of Chinese visiting scholars, and the three factors should also be at the core of the long-lasting development of the visiting scholar programs.

Conclusion

Based on two questionnaire surveys and two groups of semi-structured interviews, this study discusses Chinese visiting scholars’ cross-cultural adaptation from the perspectives of linguistic confidence, cultural confidence and academic confidence, analyzes the correlation among the three types of confidence, and then proposes the concept of establishing a positive international profile of Chinese visiting scholars.

Since linguistic confidence and cultural confidence may enhance academic confidence in a cross-cultural context, and typically, linguistic confidence is the medium of the exhibition of academic confidence, Chinese scholars should first of all improve their language proficiency and make English learning part of their daily routines. Second, they should enrich their cultural reserve and raise their cultural awareness by striking a balance between their absorption of Chinese culture and Western culture to smooth their cross-cultural communication. Also,Chinese visiting scholars should always bear in mind their identity as academics, that is,during their academic visit, they should strive to improve their academic capability, academic performance, and academic achievements by actively becoming involved in more international academic exchanges. The establishment of a positive profile of Chinese visiting scholars should be based on a systematic improvement in a profound integration of Chinese scholars’ linguistic confidence, cultural confidence and academic confidence. Chinese visiting scholars should be more open-minded, initiative, proactive, and far-sighted in the process of their academic visits.They should become the representatives of China’s international image, helping people in the host country to learn and understand more about China and Chinese culture, and should play a more active role in further internationalizing Chinese higher education.

Finally, although the study uses Chinese visiting scholars in the UK as a sample, it is believed that the notions in this paper will bring benefits for future visiting scholars from China and also for the sustainable development of the visiting scholar programs worldwide.

Implications and Limitations

This study may have implications for the following subjects: First, CSC and the domestic universities and institutions in China should enhance the concept of “mutual benefits” and“sustainable development” of the visiting scholar programs. Meanwhile, they should improve the management of Chinese visiting scholars while they are abroad by keeping a balance between supervising rigorously and granting academic freedom. Second, individual scholars planning to go abroad should thoroughly improve their English proficiency and cultural knowledge, and the eleven Ministry of Education (MOE) Training Centers in charge of visiting scholars’ language training should improve their training effectiveness and training modes to strengthen Chinese scholars’ linguistic proficiency and cultural reservoir; both the individual scholars and the eleven Training Centers should strike a balance between the input of Chinese culture and the input of Western culture. Third, more research should be conducted on the importance of and practical approaches to establishing a positive international profile of Chinese visiting scholars.

Due to the small sample sizes of both the questionnaire surveys and interviews, the participants from different universities and institutions in the UK do not represent all the Chinese visiting scholars; the 10 interviewees, including four professors and six Chinese visiting scholars from the University of York, do not represent all the mentors and Chinese visiting scholars.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Professor Helen Smith, my mentor at the University of York. Without Professor Smith’s warm support, this study would not have been possible. I would also like to thank Professor Ian Davies, Professor John Dawson, and Professor Victoria Gould for their insightful contributions to this research. I also wish to extend my thanks to all the Chinese scholars who participated in the questionnaire surveys and interviews.

Contemporary Social Sciences2021年2期

Contemporary Social Sciences2021年2期

- Contemporary Social Sciences的其它文章

- The Information Efficiency of QFII’s Investment in China’s Capital Market

- Research on the Realization Mechanism of and Approach to Ecological Product Valuations

- Research on the Cultivation of the Innovative Subcenters in Sichuan Based on the Chengdu-Chongqing Economic Circle Strategic Background

- Analysis of the Focal Issues of the Implementation of the Block System Reform in China—From the Perspective of the Protection of Civil Rights

- A Comparative Study on the Buddhist and Brahmanic Conceptions of the Relationship between the Secular World and the Emancipation Realm

- Fractal Analyses Reveal the Origin of Aesthetics in Chinese Calligraphy