Efficacy and safety of acupuncture for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Wang Ting-ting (汪婷婷),Liu Yang (劉楊), Ning Zhi-yuan (寧志遠(yuǎn)),Qi Rui(齊瑞)

1Schoolof Acupuncture-moxibustion and Tuina,ShanghaiUniversity of Traditional Chinese Medicine,Shanghai 201203,China

2College of Clinical Medicine,ShanghaiJiaoTong University,Shanghai 200025,China

3Department of Rehabilitation, Yueyang Hospital of Integrated Chineseand Western Medicine ShanghaiUniversity of Traditional Chinese Medicine,Shanghai 200437,China

Abstract

Keywords:AcupunctureTherapy;Osteoarthritis, Knee;Pain; Meta-analysis; SystematicReview;RandomizedControlled Trials

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common chronic joint disorder andcanleadtodegenerationof articular cartilage andsecondary bone hyperplasia.It often affects weight-bearing joints, such as hips, knees, spine,as well as hands and feet[1]. Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is oneof the considerablecauses of physicaldisability worldwide[2]and impairs the quality of life (QOL)[3]. Pain,swelling,stiffnessandfunctionallimitationare the primary clinical manifestations of KOA. At least 19% of adults aged 45 years or older suffer from KOA in the US[4], and the prevalence of KOA in Chinese women is muchhigher thaninAmericanwomen(46.6%vs.34.8%)[5]. Moreover, households with OA patients tend topay moreannualout-of-pocket (OOP)costsin comparison with those without OA patients[6].

There is no known cure for KOA so far. According to recent OsteoarthritisResearchSociety International(OARSI)guidelines for KOA[7],biomechanical intervention,intra-articular corticosteroids,exercise,self-management and strength training are applicable toallindividuals.Among non-surgicalapproaches,acupunctureis recommendedfor uncertainspecific clinical sub-phenotypes and has been verified to be of great benefit for pain due to OA or after replacement surgery[8-10]. Conversely, some studies have shown that there was insufficientevidenceto support the effectiveness of acupuncture in relieving pain[11-12].

Acupuncture,amajor formof traditionalChinese medicine treatment, has already become an important alternative option for KOA patients because of its fewer side effects and short-term pain relief[13]. The potential mechanismsof acupunctureinvolvebiologicaland kinetic aspects.A recent study suggestedthat electroacupuncture (EA) may slow the progression of cartilage degradation[14].Intermsof alleviating dysfunction, acupuncture can improve both short- and long-term physical function[13]and can also increase the velocity of stair climbing by developing theloading capacity of the knee joint on both sagittal and coronary planes[15].

At present,studiesassociatedwithacupuncture differ widely in their trial protocols. Thus, the results may beaffectedby considerablefactors,anditis difficult to eliminate the placebo effect of acupuncture.Moreover,there arefew high-quality randomized controlledtrials (RCTs)comparing shamandtrue acupuncture for treatment of KOA, and it is hard to obtain the effect of acupuncture from individual cases.Therefore,thismeta-analysisaimsto explore the efficacy of acupuncture and to critically evaluate the current evidencefromRCTs of acupunctureinthe management of patients with KOA.

1 Methods

1.1 Data sources and searches

This study wasconductedinaccordancewith the guidelinesof theCochrane InterventionSystematic Review[16]andCochrane Reviewers' Handbook[17]. Eight databases were extensively searched up to March 2018.RCTs comparing the efficacy of acupuncture with sham acupuncture or no acupuncture for KOA were included.Study selection, data extraction and quality assessment were independently conducted by two reviewers (Wang Ting-ting andLiu Yang). The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool wasused for assessing therisk of bias.Review Manager 5.3 and Stata 12.0 were used to conduct the quantitative analysis of the efficacy of acupuncture in the treatment of KOA.

Tworesearchers(Wang Ting-ting andLiuYang)independently searched the following databases from their inceptiontoMarch2018:CochraneCentral Register of ControlledTrials (CENTRAL),Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE), PubMed, Web of Science,ChinaNationalKnowledge Infrastructure(CNKI),Chongqing VIPDatabase (CQVIP), ChineseBiomedical LiteratureDatabase(CBM)andWanfangAcademic JournalFull-text Database(Wanfang).Thesearch strategies are shown in Table 1.In addition, we also manually retrieved eligible studies by browsing Google Scholar and reading relevant research.Language was limited to Chinese and English.

Table 1. Search strategy (taking PubMed as an example)

1.2 Study selection

RCTs comparing acupuncture with sham acupuncture(SA) or no acupuncture (NA) in the treatment of KOA patients were included.1.2.1 Inclusion criteria

RCTs;adult patientswhohadbeenclinically or radiographically diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis; the experimentalgroupwas treatedwithmanual acupuncture (MA) or EA; the control group was treated with SA or NA; pain and physical function assessed by WesternOntarioandMcMaster Universities osteoarthritisindex (WOMAC)were consideredthe outcomes; acupuncture treatment consisted of at least 6 overall sessions, at least 1 session per week and at least 20 min per time[13].

1.2.2 Exclusion criteria

Participants with KOA who had knee arthroplasty and interventions combined with other treatments such as traditional Chinese medicine; studies without needed outcomes or sufficient data.

Tworeviewers (Wang Ting-ting andLiuYang)independently selectedstudiesaccording to the inclusionandexclusioncriteria.Any disagreement wouldberesolvedthroughdiscussionwithathird reviewer (Ning Zhi-yuan).

1.3 Definitions

We definedSA astheuseof shamor placebo needles[18],whileNA representedeither standard conservativetreatment equivalentto thatof the experimental group or no routine treatment, such as education and waiting for treatment. Conventional care wastheonly additionalinterventionfor both experimentalandcontrolgroups,including pharmacological treatments,physicaltherapy,and health education[19].

1.4 Data extraction

Tworeviewers (Wang Ting-ting andLiuYang)independently extracted data from the selected studies using astandardizedformthat includedpublication year and place, authors, age of the participants, sample size, interventions, frequency and course of treatment andoutcomemeasures.Any disagreement was resolvedby negotiationwithathirdauthor (Ning Zhi-yuan).Furthermore,wecontactedthe correspondingauthors of thearticlesif therewas insufficient information.

1.5 Assessment of risk of bias

Tworeviewersindependently assessedtherisk of bias of each trialusing the CochraneCollaboration’s tool[20],whichincludessevendomains:sequence generation;allocationconcealment;blinding of participantsandpersonnel;blindingof outcome assessment;incompleteoutcomedata;selective outcome reporting and other bias. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion with a third reviewer.

1.6 Quantitative data synthesis

Statistical analysis of the data was mainly conducted using Review Manager 5.3 and Stata 12.0. We chose the standardizedmeandifference(SMD)andthe corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) to present the pooled effect size because the scores of the scales variedgreatly intheincludedtrials.We preferred changes from baseline values but used final values only if these were the only available data. If we could not obtain standard deviations (SDs) even after contacting the authors, we would then useP-value, standard error,CIsor correlationcoefficientR to calculate the final values according to the methods recommended by the Cochrane Handbook[16]. Engauge Digitizer 3.0 software was used to extract data from the figures if the studies only providedfigures[18].AP-valueless than0.05is statistically significant. The statisticI2was used to assess the size of the heterogeneity. IfI2≤50%, a fixed effects model was adopted; ifI2>50%, a random effects model wasapplied.If heterogeneity existed,sourcesof heterogeneity wouldbeexplored.If thenumber of studies was ≥10, we used Stata 12.0 for meta-regression to find the source of heterogeneity. Sensitivity analyses would be performed to evaluate whether the primary results were stable. If the number of the included trials was≥10,funnelplotsor Egger’s testwouldbe conducted to assess the potential publication bias.

1.7 Subgroup analysis

We performedsubgroupanalysesaccording to different interventions of thecontrolgroups,which could be divided into two categories: sham acupuncture and no acupuncture. Hence, we compared the effect of acupuncture versus sham acupuncture and the effect of acupuncture versus no acupuncture.

2 Results

2.1 Search results

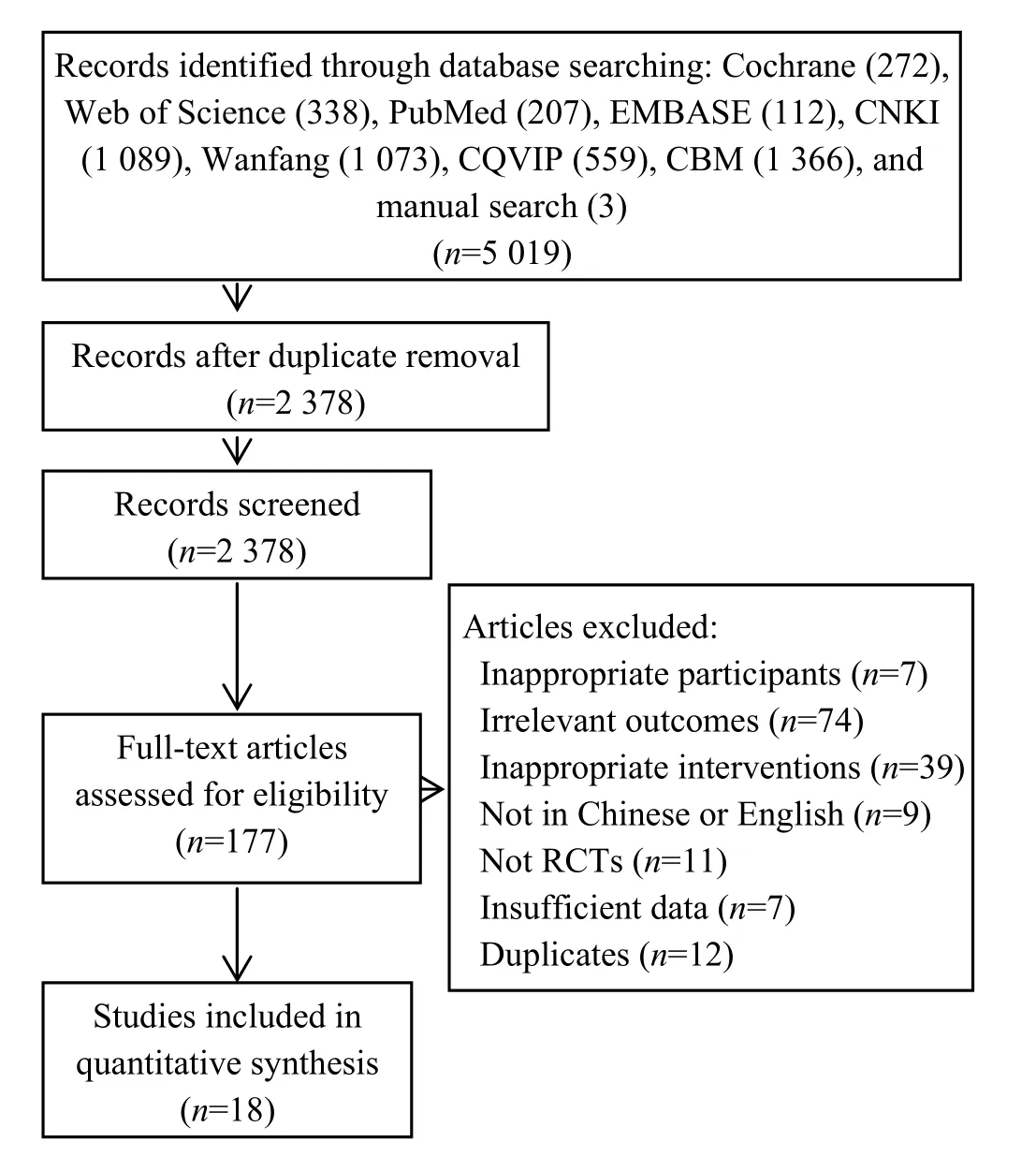

A totalof 5019recordswereretrievedthrough electronic andmanualsearch,and2378records remained after the removal of duplicates. Through title and abstract screening, 177 studies were considered to be potentially eligible. Then, we read the full texts and excluded159records for reasonslikeinappropriate participants,irrelevant outcomes,inappropriate interventions, insufficient data, in languages other than English and Chinese, and duplicates.For studies that only provided WOMAC total score or figures from which the datacouldnot be extracted,andwe failedto receive replies when contacting the authors, we would exclude them for insufficient data. Finally, 18 RCTs with a total of 3 522 participants were recruited for metaanalysis. The selection process is shown in Figure 1.

2.2 Study characteristics

Table 2 presents the basic characteristics of the 18 includedRCTs.Thesetrials werepublishedbetween 1994 and 2017; 15 in English[21-35]and 3 in Chinese[36-38].The included studies were implemented in 9 different countries.No significant differences in age, sex ratio,pain or physical function scores were detected between the experimental and control groups at baseline. The 18 RCTscomprised12comparisonsbetweenthe acupuncture group and the sham-acupuncture group,and 20 comparisons between the acupuncture group and the no-acupuncture group.Half of theincluded studies combinedroutine treatmentslikemedication and physical therapy or health education. According to whether needlepenetratedtheskin,SA couldbe dividedinto twocategories:penetrating and non-penetrating, which may have a potential impact on efficacy. Therefore, in the meta-regression, we explored therelevanceof thisfactor totheresults.Each treatmenttimewas basically 20-30 min,but the frequency varied greatly, from once per week to 5 times per week. The number of sessions also differed: one study[37]offered a total of 50 treatments, while the rest had 6-16 sessions. The duration of intervention ranged from2to13weeks,andthe assessment timewas almost within 2 weeks after the last treatment, except one trial[25], which assessed the result 3 weeks after the end of the treatment.

2.3 Risk of bias of the included studies

The risk of bias assessment is shown in Figure 2. A total of 16 trials[21-26,28-29,31-38]reported the method of random sequence generation, while theremaining 2 trials[27,30]were evaluatedas unclear.Eleven trials[21-26,28,32-35]carriedout allocationconcealment,and the rest did not describe their process of allocation concealment in detail. Because it is almost impossible to blind the operators during physical therapy, most of the studies had high or unclear risk of bias in the item of performancebias.However,5trials[22-23,26,28,32]were considered having low risk of bias in regard to this item because they evaluated the masking effectiveness after treatment,andtheresultssuggested their blinding strategies were credible. Only 4 trials[21,34,36-37]did not mention theblinding of outcome assessment.In the domain of incomplete outcome data, the control group of 3 studies[22,34-35]had a much higher dropout rate than the experimental group, and 1 study[35]even reported that several participants were lost to follow-up owing to lack of improvement, so these 3 trials were considered tohave ahighrisk of bias. Another 4 studies[30,36-38]failedto report thedropout rateandthushadan unclear risk of bias. Only 1 trial[25]had a low risk in the domain of reporting bias because the study protocol was provided prior to the trial. However, for the other bias items, 5 studies[27,30,36-38]were assessed as unclear.

2.4 Primary outcome analysis

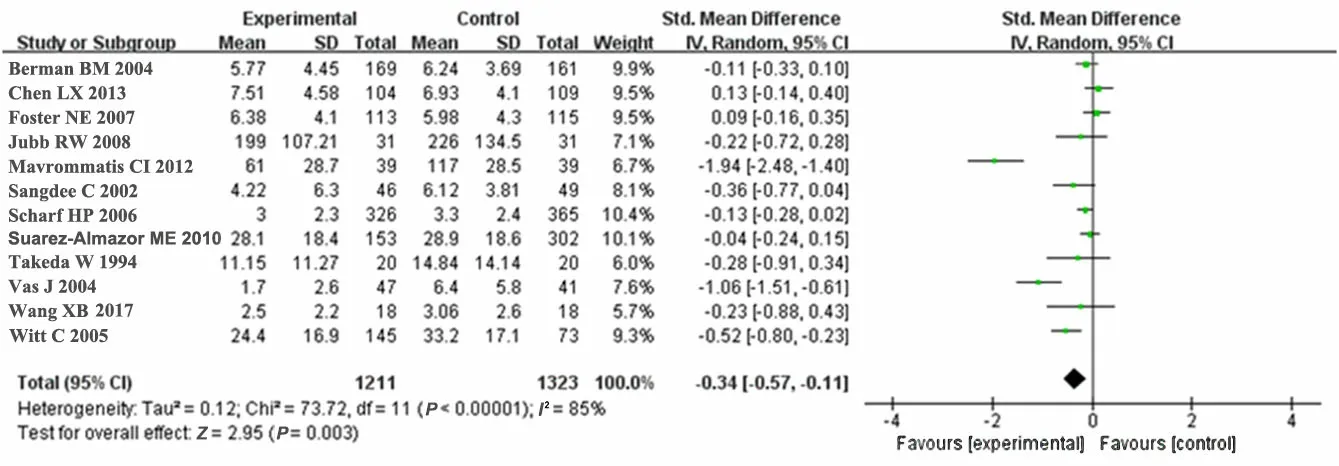

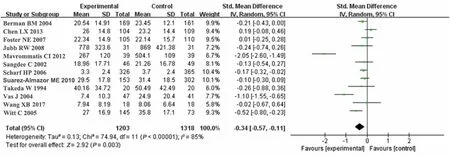

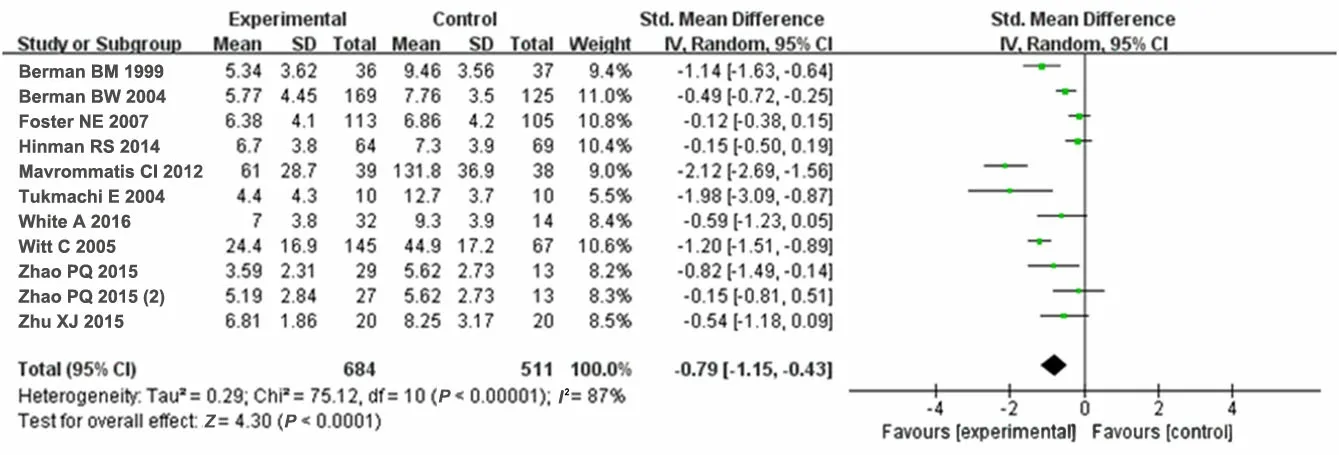

Since finalvalues wereavailablefor mostof the includedstudies,weselected thefinalvaluesfor meta-analysis. For 3 studies[22,26-27]that provided only values of changes frombaseline,weusedthe correlation coefficient R to calculate the final values and then analyzed the data of all studies. According to the control groupinterventions, a subgroupanalysis was conducted. The results showed that acupuncture was better thanshamacupuncturein painreduction(SMD=-0.34; 95%CI: -0.57 to -0.11;I2=85%;P=0.003),Figure3)andphysicalfunctionimprovement (SMD=-0.34; 95%CI -0.57 to -0.11;I2=85%;P=0.003),(Figure4).Comparedwithnoacupuncture,the acupuncture group also showed significant advantages in pain reduction (SMD=-0.79; 95%CI -1.15 to -0.43;I2=87%;P<0.0001),(Figure5)andphysicalfunction improvement(SMD=-0.75;95%CI-1.19to-0.31;I2=91%;P=0.0008),(Figure 6).However, the tests for heterogeneity showedsignificant.Therefore,we performed sensitivity analyses and meta-regression in multiple ways to find the source of heterogeneity.

2.5 Sensitivity analysis

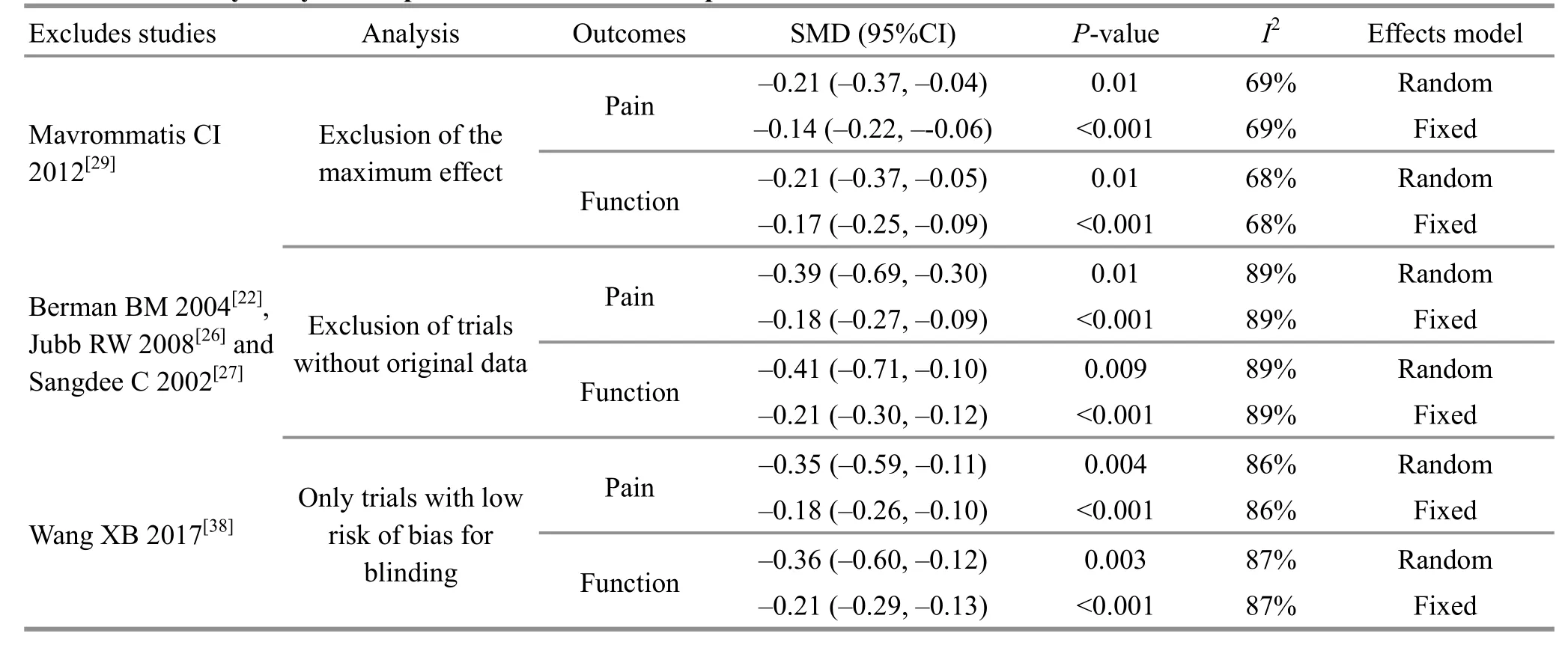

Sensitivity analyses were carried out on the basis of the subgroupanalysesusing thefollowing four methods[39]:excluding the study withthemaximum effect, excluding research with insufficient original data(studiesonly with valuesof changes frombaseline),changing the effectsmodel(random- or fixed-effects model) and including only trials with low risk of bias for blinding (at least blinding of the patients and outcome assessors).Thelastonewasonly conductedinthe comparisonbetweentheacupunctureand sham-acupuncture groups, as it is difficult to blind the patients in the no-acupuncture groups. The sensitivity analysisof theacupuncturegroupversus the sham-acupuncture group is shown in Table 3, and that for the acupuncture group versus the non-acupuncture group is shown in Table 4.

Table 2. Characteristics of the included studies

Figure 2. Risk of bias of the included studies

Figure 3. Acupuncture versus sham acupuncture for pain reduction

Figure 4. Acupuncture versus sham acupuncture for physical function improvement

Figure 5. Acupuncture versus noacupuncture for pain reduction

Notonly inthe comparisonbetweenthe acupunctureandthesham-acupuncture groupsbut also in the comparison between the acupuncture and the no-acupuncture groups, the effect sizes of the RCT by Mavrommatis CI,et al[29]for improving painand physical function were much greater than those of the other studies or thepooled effects.For example,in comparing thepainrelief effect of acupuncture with that of shamacupuncture,theeffect sizewas approximately 5 timesmore than thepooledeffect.When this RCT was excluded in the sensitivity analysis,I2decreased to a certain degree but was still substantial,while the pooled effects decreased, andP-values were as significant as before.

There were 3 studies[22,26-27]that provided only values of changes from baseline, so we excluded them in the sensitivity analysis to observe the potential effect on theresults,whichpresentedno significant changes whether they wereincludedor not.Onestudy[38]compared the effect of acupuncture with that of sham acupunctureanddidnot mentiontheblinding of patients, so we excluded it in the sensitivity analysis,and the meta-analytic estimate was very close to the primary results. When the effects model was changed,the results tended to be more conservative because in the fixed-effects model,largesamplestudieswith smaller effects occupied greater weight. In short, our primary results werestillrobust to avariety of sensitivity analyses.

2.6 Meta-regression

Univariate meta-regression was performed based on publication years and interventions. In the comparison of acupuncturewithshamacupunctureor no acupuncture group, publication years and the types of acupuncture (MA or EA) were regarded as the factors to be analyzed.In the comparison of acupuncture with sham acupuncture, we observed the influence of the types of shamacupuncture(penetrating or non-penetrating) on the results. In the comparison of acupuncturewithnoacupuncture,we exploredthe potential impact of the different interventions (whether containing routine treatmentsor not)of thecontrol group on the results. Finally, we found no significant differencesinthesefactors (P>0.05).Univariate meta-regression indicated that these covariates could not explain the heterogeneity, and these factors may not be the source of the heterogeneity.

Table 3.Sensitivity analyses:acupuncture versus sham acupuncture

Table 4.Sensitivity analyses:acupuncture versus no acupuncture

2.7 Publication bias

Egger’s test and jackknife analysis were conducted for allsubgroups.Egger’stestrevealednosignificant publication bias (P>0.05), and further jackknife analysis suggested that no test was needed to add or remove,indicating that the includedstudies wererelatively comprehensive.Jackknifeanalysis,asamethodof sensitivity analysis,also verifiedthestability of our primary results.

2.8 Adverse effects

Therewere only 3studies[29,36-38]that didnot mention adverse effects. The most common side effects includedbruising,bleeding,dizziness,nausea,numbness,excitement,weakness,musclesoreness,tingling, swelling, sleepiness, fainting, muscle cramps,headache, increased pain, infection at the acupuncture site, etc., and most of these were mild and acceptable.

2.9 Follow-up

Ninestudies[21,23,25-26,28-32]evaluatedWOMAC pain and physical function scores from 1 to 6 months after randomization, and 4 studies[21,28-30]showed that the acupuncturegroupwasstillsuperior to thecontrol group at follow-up. Two studies[25,31]even evaluated the outcomes at 1 year after randomization, and the results were negative.

3 Discussion

According to the results of this study, acupuncture wasmoreeffectivethanshamacupuncture andno acupunctureregarding painrelief andfunctional improvement.However,the effect sizesamong the eligible studies differed greatly, and there were several studies that even had much higher effect size than the pooledeffect,whichmay leadtoconsiderable heterogeneity. Notably, the effect became conservative when the study with the maximum effect was removed.Thoughmeta-regressiondidnot show asignificant difference between different types of intervention, their effect on the pooled effect could not be entirely ruled out because different treatments may lead to different effects in clinical practice.

This systematic review and meta-analysis has certain strengths. First of all, we carried out a comprehensive searchof eligiblestudies fromChineseandEnglish databasesanddemonstratedaprofoundsubgroup analysis to investigate the differences in efficacy in the twocomparisons (acupuncture versussham acupuncture and acupuncture versus no acupuncture).Besides, we conducted a variety of sensitivity analysis andmeta-regression toseek thepotentialsource of heterogeneity, and our primary results were still robust to a variety of sensitivity analyses.

Our study still has some limitations. Though various sensitivity analyses wereapplied,significant heterogeneity stillexistedandthesourcewas still unclear.Inaddition,someRCTsof thisstudy were assessed as having a high risk of bias, so the quality of evidence was downgraded because of the inclusion of these studies. And, all of the outcomes were evaluated by scales thathaveacertaindegreeof subjectivity,which may lead to bias.

In this study, we investigated the effect of the blend of bothMA andEA onosteoarthritisof theknee.Thoughmany systematic reviews andmeta-analyses oftenanalyzedtheeffectof thesetwo typesof acupuncture together in one study, compared to MA,EA displayed more significant analgesic effect for KOA[40]and displayed greater analgesic effect for different types of pain[41]. Thus, there are some systematic reviews and meta-analyses[19,42]that only focused on the effect of EA treatment of KOA because including both MA and EA may generate heterogeneity[43].

Shamacupuncture,oftencombinedwithadevice that canmakesoundsor emit light,includes penetrating andnon-penetrating shamacupuncture.The former is named minimal acupuncture[44], and the latter is named ‘Streitberger’ acupuncture[45]. Though both types of sham acupuncture have been widely used,the blinding in sham acupuncture study is still likely to fail, especially in theparticipants whohavereceived acupuncture treatment before. One study[46]found that realacupuncturetreatment hadsignificantly greater real-timepainrelief thannon-penetrating sham acupuncture,but not penetrating sham acupuncture.However,therewas no significantdifferenceinthe effect estimatebetweenthe two typesof sham acupuncture.

Other factors generating heterogeneity included the following factors:differentnumber and frequency of treatment sessions, time of each treatment, duration,evaluationtimepoints,acupoint selection,depthof acupuncture,andacupuncturist’sexperience,etc.WOMAC has been recommended as one of the highest performing outcome measuresfor knee andhip osteoarthritis,intermsof reliability,validity,responsiveness and interpretability[47-49]. It is often used as a comparator to assess the measurement properties of other outcome measures[50-51]. This scale consists of three sub-scales: pain (5 items), stiffness (2 items) and physicalfunction(17items).This scale mainly incorporates a Likert-style version and a visual analog scale (VAS) version, which may differ in efficiency[47]. In thisstudy, the two different versions wereusedfor assessment,andpartof theraw data waseven normalized to 0-10 points[28]or 0-100 points[31-32], which may result in heterogeneity.

Thereare few studies identifying theminimum clinically important difference (MCID)for thetotal WOMAC score and its component scores, and it is hard to measure MCID because it can be influenced by many factors such as age, gender, body mass index (BMI), as wellas baselineWOMAC score[52].Inthe Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook[17], the effect size of SMD can be graded as three levels: lower than 0.41, small; 0.41-0.70,moderate;higher than0.70,large.Hence, compared withshamacupuncture,acupuncture only hadmild advantage. After the study with themaximum effect wasremoved,theSMDof painandfunction improvement was reduced to 0.2, which may not have clinicalsignificance[53-54].Whilecomparedwithno acupuncture, acupuncture showed moderate to large advantage. Therefore, this meta-analysis indicated that acupuncture may be an effective treatment for pain and physicaldysfunctionassociatedwithKOA compared with sham acupuncture or no acupuncture.

4 Conclusion

Theacupuncturegrouphadsignificantadvantages over the sham acupuncture or no-acupuncture groups in relieving pain and improving physical function. And our resultswererobust toavariety of sensitivity analyses.

Conflict of Interest The authorsdeclareno conflictsof interest.Acknowledgments Thiswork wassupported by grantsfrom Project of Clinical BaseConstruction of ChineseMedicine Rehabilitation of ShanghaiHealth and Family Planning Commission (上海市衛(wèi)計委中醫(yī)康復(fù)臨床基地建設(shè)項目,No. ZY3-LCPT-1-1008).

Received:20 September 2019/Accepted:22October 2019

Journal of Acupuncture and Tuina Science2020年3期

Journal of Acupuncture and Tuina Science2020年3期

- Journal of Acupuncture and Tuina Science的其它文章

- Therapeutic observation on lung-clearing and spleen-strengthening tuina in children with exogenous cough

- Effects of electroacupuncture plus drug anesthesia on pain and stress response in patients after radical surgery for stomach cancer

- Therapeutic effect of heat-sensitive moxibustion plus medications for senile osteoporosis and its effect on serum BMP-2 and OPG levels

- Clinical observation on heat-sensitive moxibustion plus lactulose for postoperative constipation of mixed hemorrhoid due to spleen deficiency

- Therapeutic efficacy observation on auricular point sticking therapy for cardiac syndrome X in women

- Therapeutic observation of manipulation plus exercise therapy in treating upper crossed syndrome postures of primary school students