Targeted mutagenesis of amino acid transporter genes for rice quality improvement using the CRISPR/Cas9 system

Shiyu Wang, Yihao Yang, Min Guo, Chongyuan Zhong, Changjie Yan*, Shengyuan Sun,*

aJiangsu Key Laboratory of Crop Genetics and Physiology/Key Laboratory of Plant Functional Genomics of the Ministry of Education/Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Crop Genomics and Molecular Breeding, Yangzhou 225009, Jiangsu, China

bJiangsu Co-Innovation Center for Modern Production Technology of Grain Crops, Yangzhou 225009, Jiangsu, China

cAgricultural College of Yangzhou University, Yangzhou 225009, Jiangsu, China

ABSTRACT High grain protein content (GPC) reduces rice eating and cooking quality (ECQ). We generated OsAAP6 and OsAAP10 knockout mutants in three high-yielding japonica varieties and one japonica line using the CRISPR/Cas9 system.Mutation efficiency varied with genetic background in the T0 generation, and GPC in the T1 generation decreased significantly,owing mainly to a reduction in glutelin content. Amylose content was down-regulated significantly in some Osaap6 and all Osaap10 mutants. The increased taste value of these mutants was supported by Rapid Visco Analysis(RVA) profiles,which showed higher peak viscosity and breakdown viscosity and lower setback viscosity than the wild type. There were no significant deficiencies in agronomic traits of the mutants. Targeted mutagenesis of OsAAP6 and OsAAP10, especially OsAAP10, using the CRISPR/Cas9 system can rapidly reduce GPC and improve ECQ of rice, providing a new strategy for the breeding cultivars with desired ECQ.

1.Introduction

Rice is one of the most important world food crops. As rice yields increase, the demand for high rice grain quality increases with the improvement of human living standards.Rice grain quality is generally evaluated for four quality standards: processing quality, appearance quality, eating and cooking quality (ECQ), and nutritional quality. ECQ is determined by three major endosperm components: starch(80%-90%),protein(7%-10%),and lipids(about 1%)[1].Studies have focused on the genetic dissection of the mechanism underlying rice starch composition and structure [2,3]. Key genes controlling amylose content and amylopectin fine structure, including Wx, SSII-3, and SSIII-1, have been identified [3,4], and multiple alleles at the Wx locus have been identified and applied toward ECQ improvement[4].However,it has emerged that ECQ varies dramatically even in cultivars with similar amylose contents. In fact, rice grain protein content(GPC)has a negative effect on chalkiness and ECQ and leads to inferior palatability [1,5,6]. In breeding practice,cultivars with satisfactory ECQ are required to have relatively low (generally <7%) GPC [7]. Managing GPC is essential for improving rice quality,in particular ECQ.

Grain protein content is a complex agronomic trait that may be controlled by multiple minor genes and is sensitive to environmental factors. The genetic mechanisms underlying GPC are unknown,making it difficult to artificially manipulate GPC in rice breeding practice [3]. Accumulated knowledge indicates that higher protein content severely reduces the taste value of rice, owing perhaps to the high negative correlation between protein content and peak viscosity and breakdown value and to the positive correlation between protein content and hardness [8]. Reducing the protein content to lie in a certain range can improve the taste,owing perhaps to the water-holding capacity of the protein after hydration [3,6,9]. Thus, manipulating genes that control GPC may be applied in improving rice ECQ.

Of many QTL influencing GPC detected in various crosses,two have been cloned: qPC1 [10] and qGPC-10 [7], which provide targets for manipulating GPC. qPC1 is the first QTL controlling GPC that has been cloned in rice, and encodes an amino acid transporter(OsAAP6).Amino acids,the substrates for protein synthesis, play an important role in protein formation, and their transport efficiency is strongly affected by the expression levels of genes participating in the transport system[11,12].Many amino acid transporter genes have been identified in Arabidopsis, rice, poplar, potato, and soybean[13,14].Their products play an important role in the transport of amino acids between source and sink streams[15].

Eight members(AtAAP1-8)of the AAP family,with distinct functions, have been identified in Arabidopsis. AtAAP1 and AtAAP8 are involved in transportation of amino acids to seeds.AtAAP8 provides amino acids for early embryo growth;mutation in AtAAP8 reduces yield with no change in protein level [16]. AtAAP1 is the main transporter of amino acids during seed maturation [17]. AtAAP2 is highly expressed in phloem, and its mutation led to a decrease of amino acid content in leaves,resulting in the reduction of protein content in the endosperm [18]. AtAAP6 is expressed in xylem, and its mutation resulted in increased seed size[19].

Although the function of AtAAPs has been extensively studied in Arabidopsis, the role of OsAAPs in rice is largely unknown.In a genome-wide analysis[14],the rice AAP family was found to consist of 19 members. The expression level of OsAAP6 is associated with root absorption of a range of amino acids and ultimately with the biosynthesis and deposition of grain proteins[10].In contrast,high expression of OsAAP3 and OsAAP5 reduced tiller number and yield but did not affect rice grain quality[20].The functions of other OsAAP genes remain unknown.

The CRISPR/Cas9 system is the most widely used geneediting technology owing to its simple operation, mature technology, high mutation efficiency, and non-transgenic application in the field [21]. It has been applied to generate new mutants with desirable traits in many crop species,especially rice [22-26]. In the present study, we edited two amino acid transporters in three high-yield japonica rice varieties and one breeding line and measured the GPC and starch composition of the resulting mutants, with the aim of developing targeted mutagenesis for rice ECQ improvement.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Field planting and trait measurement

Rice plants were grown in an experimental farm in Yangzhou province in summer seasons and in Hainan province in winter seasons. Plants were separated by 16.5 cm in a row and 26.5 cm between rows. Field management followed standard agricultural practices.At the harvest stage,five plants of each cultivar were used for measurement of plant height, tiller number, grain number per panicle, grain shape, and setting rate. Grain length and width were determined with the YTS machine(Wanshen,Hangzhou,China).Harvested grains were air-dried and used for measurement of grain quality traits.

2.2. Vector construction and transformation

The CRISPR/Cas9 system was used to generate knock-out mutants [27]. The target sgRNAs for OsAAP6 (LOC_Os01g 65670) and OsAAP10 (LOC_Os02g49060) were CGATGGCCGCG TCAGAACAGG and GGGAAGGCGACGGCCAGACGG. The specificity of the target sites were confirmed using blast in NCBI(http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and CRISPR-GE (http://skl.scau.edu.cn/offtarget/) [28]. Off-targets with off-scores > 0.1 were located in introns or intergenic regions but not the coding sequence (CDS) (Table S1). The sgRNA under the U3 promoter was inserted into the vector pC1300-2×35S::Cas9 to generate the knockout constructs pC1300-2 × 35S::Cas9-gAAP6and pC1300-2 × 35S::Cas9-gAAP10, respectively. All the constructs confirmed by sequencing were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens EHA105 and transformed into three widely-cultivated japonica varieties, namely Yanggeng 158(YG158), Nangeng 9108 (NG9108) and Wuyungeng 30(WYG30), and one japonica breeding line named 17GTM11 by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation[29].

Specific primers Cas9-F/Cas9-R and Hyg-F/Hyg-R were used to confirm T0transgenic-positive plants.AAP6-jc-F/AAP6-jc-R and AAP10-jc-F/AAP10-jc-R were then used to amplify the target sites,which were sequenced to validate the mutation in T0and further confirmed in the T1generation. The sequence results were decoded by DsDecodeM (http://skl.scau.edu.cn/dsdecode/)[30].

In the T1and T2generation, T-DNA-free plants were selected for further analysis using the primers Cas9-F/Cas9-R and Hyg-F/Hyg-R, which both showed negative amplification.All primers are described in Table S2.

2.3. Grain protein content (GPC) measurement

For measurement of rice quality and yield traits, rice seeds were harvested 40 days after fertilization and stored at room temperature for 3 months to stabilize moisture content.Dried seeds were dehulled into brown rice by TR 200 dehuller(Kett,Tokyo, Japan), milled by Pearlest rice refiner (Kett, Tokyo,Japan) and then grinded into flour by cyclone crusher (FOSS AB, Hoganas, Sweden). A Kjeltec 2300 (FOSS AB, Hoganas,Sweden)was used to measure crude GPC and storage protein components in the flour.GPC was calculated using a nitrogen conversion coefficient of 6.25. The four components of protein, albumin, globulin, prolamin and glutelin were sequentially extracted from 150 mg rice flour each sample using respectively 1 mL ddH2O, 1 mL extraction buffer (pH 6.8)containing 50 mmol L?1KH2PO4, 0.5 mmol L?1NaCl and 1 mmol L?1EDTA-2Na, 1 mL 75% ethanol and 1 mL solution containing 0.1 mol L?1NaOH and 1 mmol L?1EDTA-2Na.Each extraction was performed by shaking at 4 °C for 6 h and centrifugation at 10,000×g for 15 min,repeated 3 times.

2.4. Amino acid determination

For each sample, 10 mg rice flour was hydrolyzed in a 2 mL screw-cap tube by addition of 1 mL 6 mol L?1HCl containing 10 nmol L-(+)-norleucine(Wako Pure Chemicals,Osaka,Japan)as internal control.The solution was held in a 110°C oven for 24 h to complete hydrolysis. The sample was evaporated in a 60 °C water bath until completely dried and dissolved in 500 μL sodium buffer (80-2037-67, Biochrom, Cambridge,England). Samples were centrifuged at 1600 ×g for 10 min after complete dissolution and the supernatant was filtered with an 0.45 nm nylon membrane. An automatic amino acid analyzer (Biochrom, Cambridge, England) was used to determine amino acid contents.

2.5. Measurement of pasting properties

To determine rice pasting properties, 3 g rice flour and 25 g water were mixed in a sample can. A Rapid Visco Analyser(Model 3-D, Newport Scientific, Warriewood, Australia) was used to measure peak viscosity, hot viscosity, final viscosity,breakdown value (peak viscosity - hot viscosity), setback viscosity(final viscosity-peak viscosity)and pasting temperature. The program of the RVA cycle was as follows:50 °C for 1 min, 95 °C for 2.5 min, 50 °C for 1.4 min. The heating and cooling time were set for 3.8 min.The RVA paddle rotated at a constant speed of 160 r min?1,except in the first 10 s when the speed was 960 r min?1.

2.6. Taste value measurement

Polished rice (30 g) was washed four to five times with tap water and soaked in water for 30 min before cooking. Each sample was cooked in an MB-YH16 model rice cooker(Midea,Guangdong, China) at a ratio of polished rice: water = 1.0:1.3.After steaming for 30 min and simmering for 10 min,the rice was cooled in a cooling box for 10 min.A sample of 8.00 g was used for measuring taste value in the taste analyzer STA/A(Satake,Tokyo,Japan).

2.7. RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from tissues containing root, shoot,leaf,leaf sheath, and endosperm from Nipponbare at 25 days after flowering using an RNA extraction kit(TIANGEN,Beijing,China). A Reverse transcription kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China)was then used for synthesizing first-strand cDNA with 2 μg total RNA. qRT-PCR was performed with a total volume of 25 μL containing 2 μL of the cDNA product, 0.25 mmol L?1gene-specific primers,and 12.5 μL SYBR GreenMasterMix on a CFX96 Real-time PCR system (Bio-rad, Hercules, CA, USA)according to the manufacturer's instructions. The rice actin gene (LOC_Os03g50885) was used as reference. Primers used for qRT-PCR analysis are listed in Table S2. A relative quantification method[31]was used for the measurements.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Three independent samples were taken from each genetic background for measurement of GPC, amino acids, RVA, and taste value in a mixture of T-DNA-free T1plants from several T0events.For agronomic trait measurement,five plants from one T2line were used. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 15.0(IBM,Armonk,NY,USA).

3. Results

3.1. Generation of OsAAP6 and OsAAP10 mutations

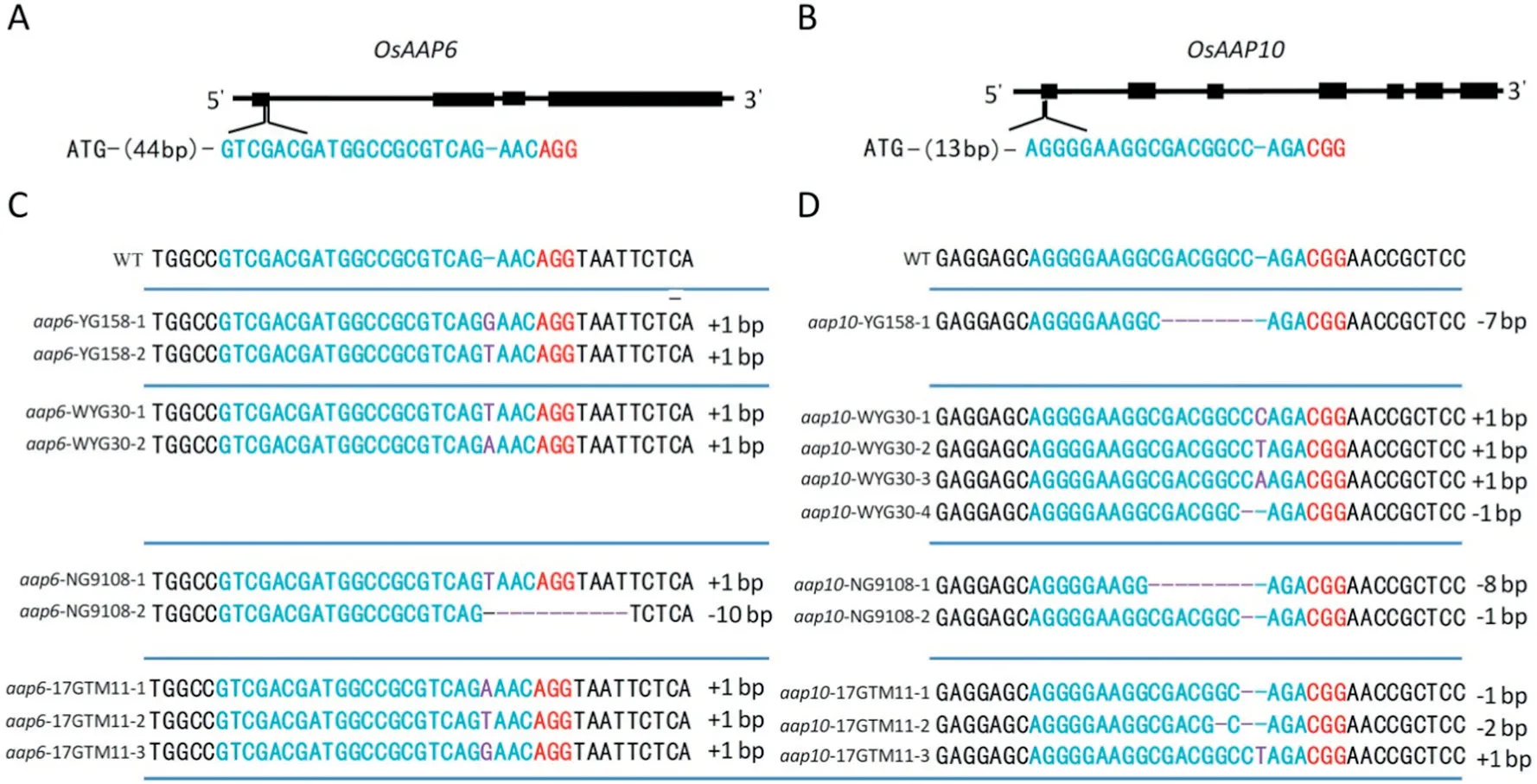

The expression level of OsAAP6 was associated with GPC variation in indica accessions but not validated in a japonica genetic background [10]. We designed a CRISPR/Cas9 construct to edit OsAAP6 in the first exon(44 bp downstream from ATG) (Fig. 1-A), which was expected to cause mutation in the coding region and thus inactivate the OsAAP6 protein,reduce the protein level,and increase ECQ in YG158,NG9108,WYG30,and 17GTM11.In the T0generation,we obtained 18,23,24,and 22 independent transgenic plants, sequencing of which showed that 14, 15, 23, and 22 plants were successfully knocked out. The respective mutation efficiencies were 77%,65%,95%,and 100%in the four genetic backgrounds(Table S3).

(A,B)Schematic map of the genomic region of OsAAP6 and OsAAP10. The sgRNA target sites are shown in blue and the PAM motif (NGG) is shown in red. (C, D) Sequence alignment of the sgRNA target region showing altered bases in mutant lines.Mutated sequences are shown in purple.

In qRT-PCR analysis, another family member, OsAAP10 also showed an expression level as high as that of OsAAP6 in the endosperm, compared to the expression in the leaf and leaf sheath (Fig. S1). To validate its function in protein level regulation, another CRISPR/Cas9 construct targeting the first exon (13 bp downstream ATG)of the OsAAP10 was generated(Fig. 1-B). The OsAAP10 CRISPR/Cas9 construct was also transformed into the four genetic backgrounds. The T0generation revealed respectively 15, 21, 18, and 20 independent transgenic plants, of which 10, 20, 14, and 20 were confirmed by sequencing of the mutated region. The respective mutation efficiencies were 67%, 95%, 78%, and 100%(Table S3).

Fig.1- CRISPR/Cas9-induced Osaap6 and Osaap10 mutants.(A-B) Schematic map of the genomic region of OsAAP6 and OsAAP10;the sgRNA target sites are shown in blue;The PAM motif(NGG)is shown in red.(C-D)Sequence alignment of the sgRNA target region showing altered bases in different mutant lines.Mutated sequences are shown in purple.

To produce stable mutants without the CRISPR construct,one to three T0lines of each transgenic evidence were selfpollinated. Several randomly selected T1plants derived from each T0line were genotyped individually at the target site and analyzed using PCR amplification with Cas9-specific primers(Table S4). T-DNA-free mutants were observed in the T1generation. Insertion and deletion of various nucleotides that would cause frame shifts were confirmed in each background (Fig. 1-C, D). All of the mutations were also detected using the Cas9-specific and Hyg-specific primers in the T2progeny, and PCR assays all yielded negative results.This finding confirmed the elimination of the T-DNA and the inheritance of the mutations in later generations, suggesting that stable mutants without exogenous transgenic DNA could be produced after a few generations.

3.2.Grain protein content(GPC)of the OsAAP6 and OsAAP10 mutants

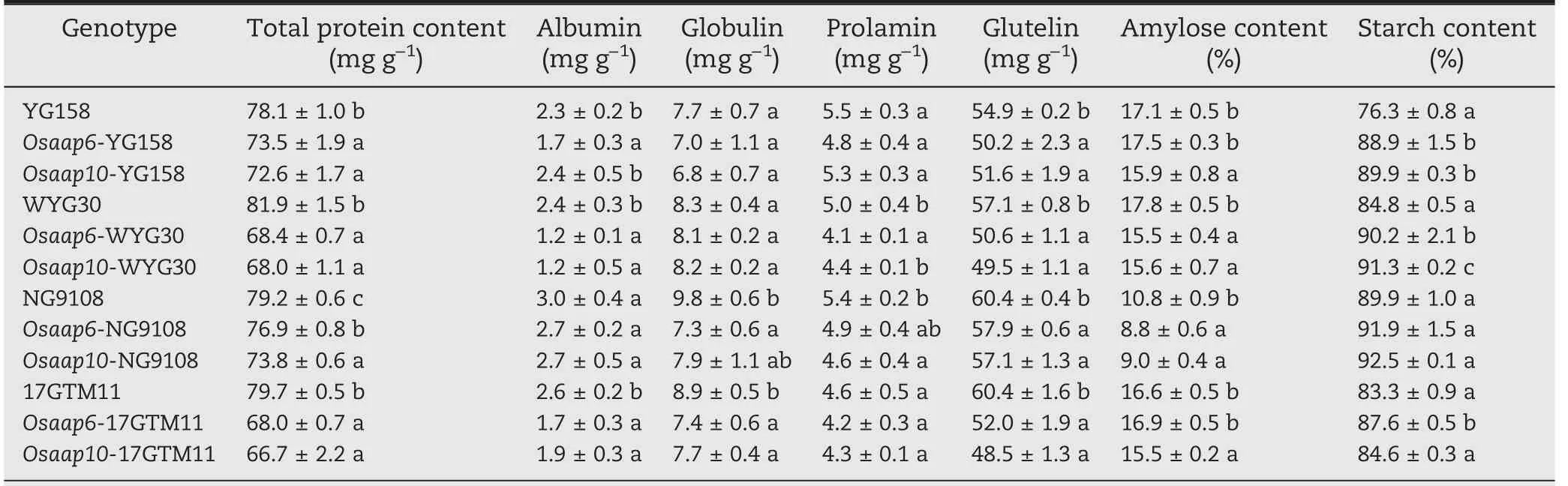

A mixture of rice seeds from independent T1T-DNA free plants were used to quantify the effects on GPC of loss of function of OsAAP6 and OsAAP10 in all of the tested japonica varieties(Table 1).In comparison with the WT,the GPC values of the Osaap6 and Osaap10 mutants were significantly decreased by respectively 16.5%, 14.7%, 5.9%, 2.9% and 17.0%,16.3%,7.0%,6.8%in YG158,NG9108,WYG30,17GTM11.GPC in Osaap10 mutants generally decreased more than that in Osaap6 mutants in each background. However, this effect difference was statistically significant only between Osaap6-NG9108 and Osaap10-NG9108 and not in the other three genetic backgrounds, suggesting that the mutations ofOsAAP6 and OsAAP10 had similar effects on GPC reductions with a slightly stronger effect in OsAAP10.

Table 1-Grain quality traits of mutants and wild-type plants in T1 generation.

The contents of the four storage proteins, especially glutelin, were significantly decreased in Osaap6 and Osaap10 mutants, with the extent of decline of albumin,globulin, and prolamin varying among genetic backgrounds (Table 1).Except for Osaap10-YG158, Osaap6-NG9108, and Osaap10-NG9108, albumin showed significant decreases in all genotypes in comparison with their counterparts. Only Osaap6-NG9108, Osaap6-17GTM11, and Osaap10-17GTM11 showed significant decreases in globulin, whereas significant decreases in prolamin were detected only in Osaap6-WYG30 and Osaap10-NG9108 relative to the wild type. These results indicated that the reduction of glutelin content is the main reason for the decrease of GPC in the Osaap6 and Osaap10 mutants.

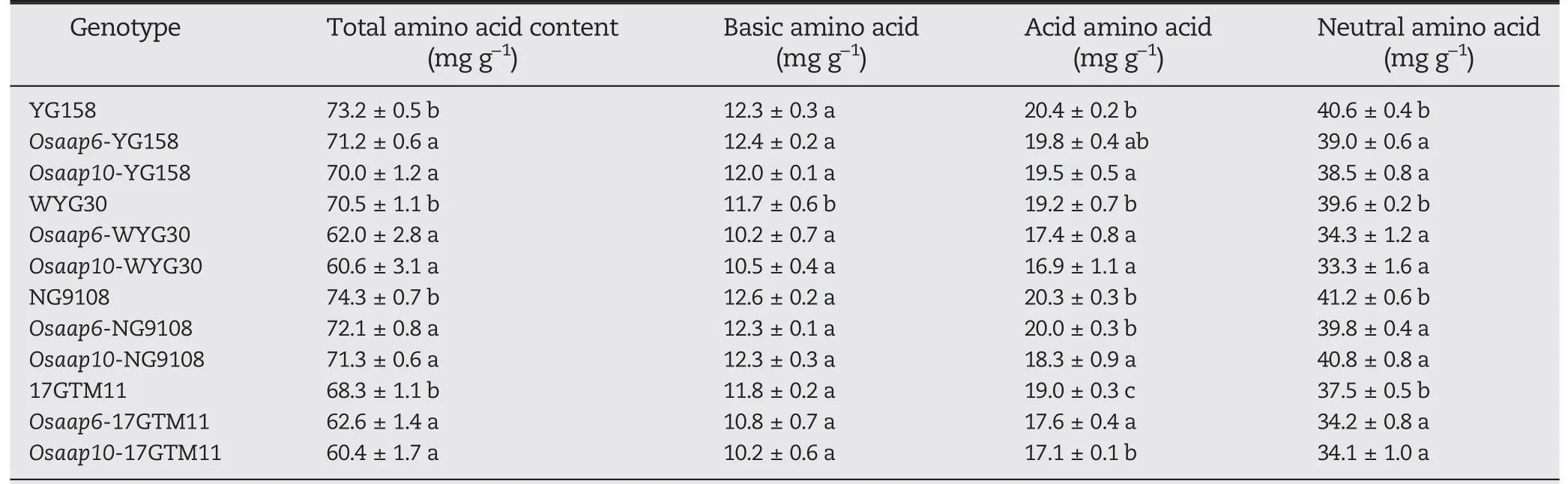

3.3. Amino acid content in Osaap6 and Osaap10 mutants

Loss-of-function mutations in OsAAP6 and OsAAP10 may interfere with amino acid transport, resulting in a reduction in protein levels. For this reason, we measured amino acid contents in the grains of Osaap6 and Osaap10 mutants. Total amino acid contents decreased in all Osaap6 and Osaap10 mutants (Table 2). Among the Osaap6 mutants, Osaap6-WYG30 showed the greatest reduction, followed by Osaap6-17GTM11, Osaap6-YG158, and Osaap6-NG9108, displaying the same trend as the GPC decrease. In agreement with the Osaap6 mutants, total amino acid contents showed higher reductions in Osaap10 mutants in the same genetic background and followed the same trend as the protein-content decline. The amino acids affected differed between Osaap6 and Osaap10 mutants.Neutral amino acids were significantly affected in all Osaap6 and Osaap10 mutants, but basic amino acids decreased only in the WYG30 background. The acidic amino acids decreased significantly in all OsAAP10 mutants,but only in Osaap6-WYG30 and Osaap6-17GTM11(Table 2).

3.4. Starch content and physicochemical properties

Most of the mutants showed higher starch contents than their wild types,except for mutants with NG9108 as genetic background and Osaap10 mutants in 17GTM11. Amylose contents showed a decreasing trend, with most of the mutants showing lower contents. In Osaap10 mutants,amylose content was decreased by 6.6%-16.7% (Table 1).These results showed that mutations in the OsAAP6 and OsAPP10 not only affect GPC in grains, but also change starch content and composition.

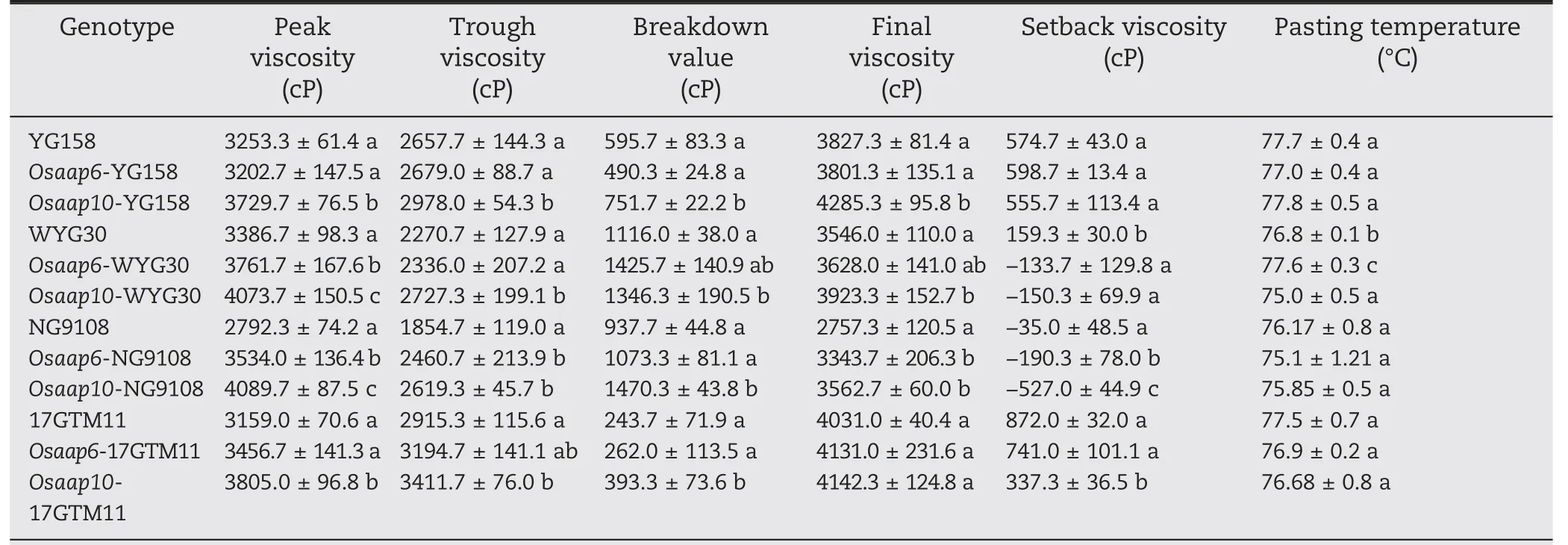

The RVA test, which simulates the rice cooking process and measures the pasting properties of the starch,is a proven tool for the assessment of rice ECQ. Peak viscosity (PV),Trough viscosity (TV), and Breakdown value (BDV) were increased in all Osaap10 mutants compared to the wild type.The Final viscosity (FV) of Osaap10-WYG30, Osaap10-YG158,and Osaap10-NG9108 increased,whereas the Setback viscosity(SBV) of Osaap10-NG9108 and Osaap10-17GTM11 decreased.Only Osaap10-WYG30 showed a significant decrease in the pasting temperature analysis. Osaap6 mutants showed the same trends as Osaap10,but revealed less effect than Osaap10.PV increased only in Osaap6-WYG30 and Osaap6-NG9108,while TV, FV, and SBV decreased only in Osaap6-NG9108(Table 3).

3.5. Taste quality in Osaap6 and Osaap10 mutants

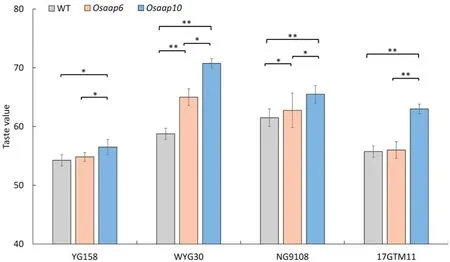

To investigate whether mutation of Osaap6 or Osaap10 increased taste quality, we further quantified taste values in all mutants(Fig.2).All the Osaap6 mutants showed increased taste value, but only those of Osaap6-WYG30 and Osaap6-NG9108 were statistically significant(Fig.2).Osaap10 mutants showed effects similar to but more powerful than those in Osaap6.All the Osaap10 mutants showed significant increases in taste value compared to the wild type. Taste values in Osaap10 mutants were higher than those of Osaap6 mutants in all four genetic backgrounds. These results indicate that taste quality can be improved by the editing of Osaap6 or Osaap10. However, the utilization of Osaap6 is genetic background-dependent.

3.6. Agronomic trait in Osaap6 and Osaap10 mutants

The agronomic traits of Osaap6 and Osaap10 mutants in the four genetic backgrounds are described in Fig.S2 and Table S5.In the Osaap6-YG158 mutant,plant height was decreased,but the number of grains per panicle was increased, whereas Osaap10-YG158 showed increased tiller number.Both Osaap6-WYG30 and Osaap10-WYG30 mutants showed increased plant height, grain length, and 1000 grain weight. Both Osaap6-WYG30 and Osaap10-WYG30 mutants showed a slight reduction in setting rate.The OsAAP6 mutation led to a decrease in plant height, whereas Osaap10 increased tiller number in the 17GTM11 background.

Table 2-Amino acid content in grains of mutants and wild-type plants in T1 generation.

Table 3-RVA profile of mutants and wild plants in T1 generation.

4. Discussion

CRISPR/Cas9 has become a useful tool for editing genes that may be used in breeding in several species [22,32-34]. In the present study, editing two AAP-family genes OsAAP6 and OsAAP10 resulted in reduced GPC and improved taste value in some or all of three japonica rice cultivars and one breeding line. Editing both OsAAP6 and OsAAP10 reduced amino acid transportation, thereby reducing protein content. The effects differed by genetic background, with mutation of Osaap6 reducing protein content by 2.9%-16.5% and that of OsAAP10 by 6.8%-17%. Both OsAAP6 and OsAAP10 showed relatively high expression in endosperm, but only OsAAP10 was relatively highly expressed in the shoot.

In this study, the function of OsAAP10 was similar to that of OsAAP6, but its effect was stronger than that of OsAAP6.This difference may be due to the high expression of OsAAP10 in roots and stems (Fig. S1), which led to a reduction in longdistance amino acid transport efficiency in the mutants.Another reason may be due to their different preferences for transporting different amino acids. Our results showed that OsAAP6 affects mainly the transport of neutral amino acids,whereas OsAAP10 regulates both neutral and acidic amino acids(Table 2).

OsAAP6 may indirectly affects key genes for starch biosynthesis [10]. Increasing OsAAP6 expression can result in increased amylose content (AC) which negatively correlates with rice ECQ [35]. Mutation of Osaap10 significantly changed starch composition by reducing AC in all four genetic backgrounds. However, mutation of Osaap6 reduced AC only in WYG30 and NG9108 (Table 1). The reduced GPC together with the amylose content both contributed to the increased ECQ.

Fig.2- Taste value of mutants and wild plants in T1 generation.Values are given as mean±SEM(n= 3). *and** indicate significant differences at P <0.05 and P <0.01 respectively by one-way ANOVA with Duncan's multiple range test.

The improved ECQ was further supported by RVA test which is an important index of rice taste quality. The degree of stability determined by the ease of disrupting swollen starch granules was measured by breakdown viscosity(BDV),peak viscosity(PV),and trough viscosity (TV) [36]. Gel consistency is highly correlated with BDV [37]. The degree of retro-gradation or hardening of starch during cooling is revealed by setback viscosity(SBV)which is calculated as the difference between final viscosity (FV) and peak viscosity (PV). A low SBV value is associated with softness and desirable sensory qualities of cooked rice.High-ECQ varieties usually have higher BDV and lower SBV than inferior-ECQ varieties[38].PV,TV and BDV increased in all Osaap10 mutants,whereas SBV decreased in Osaap10-NG9108 and Osaap10-17GTM11. Only Osaap6-WYG30 and Osaap6-NG9108 increased PV, while Osaap6-NG9108 decreased TV, FV, and SBV. In consistent, the taste values of Osaap10 mutants in all four backgrounds and of Osaap6 mutants in WYG30 and NG9108 were improved (Fig. 2). Meanwhile, mutation of OsAAP6 and OsAAP10 do not show obvious deterioration in agronomic traits(Fig.S2 and Table S5).By developing non-transgenic cultivars by self-pollination in which transgenes can be allowed to segregate out,we can use these two genes to control protein level.

5. Conclusions

We used a CRISPR/Cas9 system to edit two amino acid transporter genes, OsAAP6 and OsAAP10, in three japonica cultivars and one breeding line, yielding homozygous plants in each background. Grains from mutated plants showed decreased amino acid content and protein levels.Mutation of Osaap10 in all four materials and mutation of Osaap6 only in WYG30 and NG9108 increased rice ECQ.These results suggest that using CRISPR/Cas9 technology can bring about rapid improvement of rice grain quality.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China(2016YFD0100501),the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31871241,31371233),the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province(BE2017345, PZCZ201702, BE2018351), the Research and Innovation Program of Postgraduate in Jiangsu Province(KYCX17_1886), the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions, and the Yangzhou University International Academic Exchange Fund.

Author contributions

CY conceived and designed the research. SS, YY, and SW performed the experiments. CZ assisted in vector construction and contributed reagents, materials, and analysis tools. SS and CY analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Appendix A.Supplementary data

Supplementary data for this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cj.2020.02.005.

- The Crop Journal的其它文章

- Brief Guide for Authors

- Crop genome editing: A way to breeding by design

- Less and shrunken pollen 1 (LSP1) encodes a member of the ABC transporter family required for pollen wall development in rice (Oryza sativa L.)

- OsABA8ox2, an ABA catabolic gene, suppresses root elongation of rice seedlings and contributes to drought response

- Mutagenesis reveals that the rice OsMPT3 gene is an important osmotic regulatory factor

- Precise base editing of non-allelic acetolactate synthase genes confers sulfonylurea herbicide resistance in maize