The Historical Development of Literary Anthropology in China

Xu Xinjian*

Abstract: From a perspective of the correlation between literature and anthropology, this paper unveils the background and characteristics of literary anthropology as an emerging subject. Through contrastive analysis of two correlative fields,this paper focuses on “l(fā)iterary issues” and “anthropological issues,” highlights literature’s anthropological turn and the interaction between anthropology and literature, and reviews the brief history of literary anthropology in contemporary China.

Keywords: Chinese literature; anthropology; literary anthropology

1. An interdisciplinary approach to literature and anthropology

Since the “introduction of Western learning to China” (a historical trend starting from the late Ming Dynasty), the academic system of China has been in the process of constant reform and reconstruction. Through over one hundred years of evolution, a complete subject system with its special division of teaching and research has gradually developed. This system is based on the “three legs of a tripod,” namely, Western natural sciences, social sciences and humanities, each of which is within their own boundary and independent of each other. Nowadays,constantly challenged by the academic community and influenced by a real demand from society, the existing subject system and its divisions are involved in a new round of subject crossovers and restructuring. This trend has a wide-reaching effect on almost all subjects and can be exemplified by the development of “l(fā)iterary anthropology” in contemporary China.

Since modern times, through long-term Sinicization, many academic areas, including literature and anthropology, have completed linguistic and terminological localization. The relentless efforts made by generations of Chinese intellectuals enable the academic narration of literature and anthropology in Chinese. This in fact concerns the representation of a nation, behind which lies an almost forgotten fact that the current academic narration in Chinese is an adaptation of the imported Western learning.The seemingly oriental path is in nature a reflection and imitation of foreign literature and anthropology.In an age featuring worldwide interdisciplinarity and category-restructuring, literature and anthropology,the two seemingly irrelevant independent academic categories, are approaching each other without prior consultation. Such a trend is also manifested in contemporary China. With a strong influence from Western learning since their introduction to China,literature and anthropology, believed to have been localized, are becoming more and more intertwined and compatible with each other.

Zhang Zhidong

During China’s “introduction of Western learning”, Zhang Zhidong argued in his China’s Only Hope: An Appeal, that “the empowerment of China and the survival of traditional Chinese learning cannot be achieved without reference to Western learning.” Later, Kang Youwei also stressed, “Much of the new Western learning is exactly what China lacks. It is imperative to establish special organizations to translate such learning into Chinese.”①Association of Chinese Historians, 1953, p.119Under such circumstances, institutions of higher education established in succession since the late Qing Dynasty were primarily based on a Western-style subject classification. Within such a classification framework, literature enjoyed an important and independent place. It was arguably a representative of humanities between natural and social sciences, and also shouldered the missions of social mobilization and national character reshaping.With the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, literature was incorporated into Chinese departments or foreign language departments,becoming a platform that carried forward domestic traditions and enabled Chinese people to access the outside world. The full name of a Chinese department should be the department of Chinese language and literature. However, due to multiple restrictions concerning region, concept and faculty, for a long time, many universities in China, including Peking University, Nanjing University and Fudan University,only offered a “Han Chinese language program,”which could not entirely represent and inherit China’s multi-ethnic literature. At the same time, highereducation programs offered by institutions in ethnic minority areas tended to only highlight the local language, literature and culture, which lacked a comprehensive approach to Chinese literature.

Such a binary system of literature classification was not conducive to the interpretation and passingon of China’s multi-ethnic literature. With the formulation and implementation of national policies promoting ethnic unity, Chinese literature as a subject-and-education category interacted with ethnology and anthropology, and thereby took an interdisciplinary and compatible path. With the advancement of the reform and opening-up policy in the new era, the once isolated foreign literature education in China, driven by the tide of comparative literature and comparative culture,began to embrace “influence study,” “parallel study” and “world literature.” The “influence study”highlighted specific differences and relevance between countries; the “parallel study” attached importance to interdisciplinary dialogues; the vision of “world literature” called for more attention to global care. The emergence of these new phenomena not only required an integration of literature with anthropology to echo the call of the times, but also provided solid social support for it.

Through the joint efforts of generations of scholars, literary anthropology, featuring interdisciplinarity, was included in the subject catalogue of the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, and thus became a new academic platform. Established in 1993, the Research Society of Chinese Literary Anthropology under the Chinese Comparative Literature Association has launched the literary anthropology program and research base in a number of universities in China, including Sichuan University, Xiamen University and Shanghai Jiaotong University. In the summer of 2012, approved by the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, the first literary anthropology training session for college teachers was jointly held by these universities, which marked the beginning of literary anthropology’s new journey in China.①Liu, 2012

2. A question of “l(fā)iterature:”Reflections on Chinese word translation

What is literature? There must be a variety of answers to this question. It has triggered heated debate among scholars and shifted the academic focus to “l(fā)iterariness.” So far, numerous attempts have been made to define literature and to determine whether online/mobile contents, text message and even advertising slogan can be counted as forms of literature. Some scholars think so because the notion of literature keeps developing. Some are against it because, in their opinions, literature should not be generalized and that the essence of literature is about aesthetics. Thus, no consensus has been reached over what literature is. Not many people have realized that a clear definition of literature should be initiated prior to the discussion of “what literature is”. Without a comparison with “l(fā)iterature” in the Western world, there is no way for scholars in China to truly understand the meaning of “l(fā)iterature” in the Chinese language. Prior to modern times, Chinese people seldom touched upon the concept of literature,or deliberately discussed literature. In most cases,the Chinese character “文” (wen, meaning writing)was used to serve similar purposes. According to The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons, the word“wen” had many different meanings and was selfcontained, for which it could hardly be corresponded to “l(fā)iterature” and to some extent transcended the latter. In this regard, there were some “doublecharacter” words (Chinese compounds), which were interrelated and at the same time distinct from each other. Examples of such “double-character” words included “文章” (wenzhang, meaning articles),“文采” (wencai, meaning literary talent), “文筆”(wenbi, meaning styles of writing, “文韻” (wenyun,meaning literary charm), “文理” (wenli, meaning unity and coherence in writing) and even “文道”(wendao, meaning literary form). Why was the word“文學” (wenxue, meaning literature) retained and highlighted as the correspondence of “l(fā)iterature”while others were not retained in modern China?From a perspective of discourse alteration, such a phenomenon manifested a genealogical aphasia in corresponding academic studies. When no related view was voiced, there was no other choice but to adopt the translated term “wenxue” (literature) to express the time-honored and transnational notion.

In terms of translation, however, the word“wenxue” (literature) is problematic. Like other translated words of modern times, such as “huaxue”(chemistry), “suanxue” (arithmetic), “qunxue”(sociology), the root of “wenxue” is “xue” (study),which highlights its status as a knowledge and a subject. This is in fact in conflict with the Western categorization of literature as part of the arts and confuses abstract academic theory with vivid creation, resulting in ambiguous and vague meanings in its Chinese translation. The English word‘’literature” with its Latin root literatura/litteratura(derived itself from littera: letter or handwriting),was later used to refer to the art of written works. So literature was understood as an “art,” rather than a“study” in the West. Even today, when asked what literature is, a literature major will surely answer that literature is an art. Yet, the department of literature at any university of China does not aim to train writers, but literature researchers. That is why China’s literature program focuses on courses like the history of literature, literary criticism and theories of literature, not literary creation.

Given this, I hold that “wenxue” (literature) in modern Chinese is a problematic pseudo-word. What is the problem? The problem lies in the latter part of this compound word, i.e. “xue” (meaning study in Chinese). If literature is understood as an art, a discipline or subject about literature should be named“wenxue xue” (the study of literature). The study of literature is a subject, just like the study of physics is a subject. Likewise, the so-called comparative literature has the same problem. A subject on comparative study of literature should be called comparative literature study.

3. An anthropology-based probe to examine Western-style subjects

The second subject that is closely related to literary anthropology is anthropology. In such an open era, anthropology is supposed to be known by all. This term has been more and more extensively applied. It was used in the opening ceremony of the 2012 London Olympics. Both in official and non-official contexts, from scholars to media professionals, many people use anthropology as an academic term and an interpretive tool to demonstrate national image and ethnic identity. Yet,these are only superficial phenomena. In fact, the public knows even less about anthropology than literature.

China’s anthropology, imported from the U.K.and North America includes four categories.

The first category is biological or physical anthropology, which is more of natural science and focuses on the studies of human species, origins,evolution, distribution and also genetic inheritance. In this regard, for example, to identify the physical characteristics of one ethnic group in south China, relevant researchers have to offer them trainings on biological/physical anthropology; then they need to sample some members from that ethnic group for height measurement, blood typing and gene testing; based on thorough analysis and comparison, they are expected to come to a corresponding conclusion. Physical anthropology is arguably a classic category and approach.

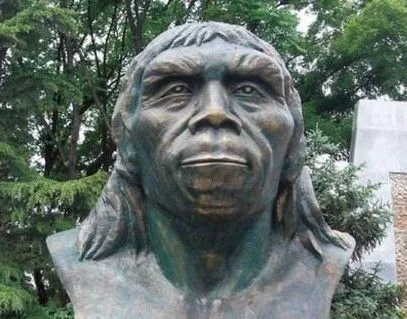

The second category is archaeological anthropology. Mainly focusing on ancient human civilizations and extinct cultural relics, archaeological anthropology has exerted significant impact on the knowledge genealogy of the world today. As it has re-constructed prehistoric civilizations and evolutionary hierarchies based on scientific evidence,archaeological anthropology enables the formation of various “pre-histories,” which are unified yet distinctive, for different ethnic groups around the world. Archaeological anthropology also has a profound influence on China, a country with a long uninterrupted history. The discovery and interpretation of ape-man fossils at Zhoukoudian, along with many other prehistoric sites at Yangshao, Hongshan, etc.,inspired scholars and government officials to prove China’s 5000-year history and translate the ancient legends and imaginations into scientific facts. Now,more and more regions in China hope to re-shape their cultural traditions, highlight local presence and increase social capital through archaeological excavation. In other words, they utilize archeology to re-write history. Recently, there have been production crews from China Central Television (CCTV) engaged in live broadcasting the unearthing of some ancient tombs, which are believed to belong to renowned figures in ancient China. Why is archeology, a branch of anthropology, extensively accepted as a new competitive edge? That is because archeology enables the unearthing of more cultural relics, which can be traded for profits and, more importantly, can develop a strong discourse power capable of conveying stories simply beyond the description of written words.Although it has not been long since archeology was first introduced to China, this subject has already attracted extensive attention from all walks of life.Museum construction has now become a fashion competing for more say in historical culture through archaeological narratives. Such a context gives rise to a new approach to the representation of China.The origin of this new approach can be traced to recent Chinese history. It started with the discovery of the Peking Man Site at Zhoukoudian, through the discovery of the Yuanmou Man Remnants at Yuanmou County and the discovery and promotion of the Yangshao culture in Central China, to the recent promotion of the Hongshan culture in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region and the Sanxingdui Ruins site in the Chengdu Plain. These discoveries and excavations have significantly changed the general public’s collective cognition of China, the Chinese people and the history of China.

Peking Man Relics at Zhoukoudian Site

The third category is linguistic anthropology. It is an important and difficult category of anthropology.Nevertheless, linguistic studies today are not much favored by the academic community. As a result linguistic anthropology fails to attract high attention.When it comes to cultural identity, the inclination of “ethnocentrism” can easily narrow the scope and vision of linguistic studies to the mother tongue of each ethnicity (such as Han Chinese, Tibetan or Mongolian) and overlook the languages of other ethnicities. However, as one of the earliest pillars of anthropology, linguistic studies are of great significance to the explanation of mankind and their cultural functions. It is characterized by its abstract and profound structural analysis of human linguistic phenomena and its comparative study of speech acts among different ethnic groups.

The fourth category, according to the Anglo-American classification system, is cultural and social anthropology which is already familiar to many and therefore needs no more elaboration. Still, it is noteworthy that such a classification system is not universal, but quite region-specific, for which the four categories can be regarded as “l(fā)ocal knowledge” of anthropology. Besides, archaeological anthropology and linguistic anthropology are increasingly powerful and independent. Under such circumstances, even in the U.S. and the U.K., anthropology is now reduced to two main categories: biological/physical anthropology and cultural/social anthropology.①Xu, 2008

Through over 100 years of development and evolution, cultural/social anthropology is now more influential in China. As a result of such a biased scope-narrowing, some scholars claim that anthropology is a “study of otherness” which focuses on the common features and historical changes of different cultures.

Different from the Anglo-American version,the classification of anthropology on the European Continent traditionally follows a tripartite method,according to which anthropology mainly falls into three categories, i.e. biological/physical anthropology,cultural/social anthropology and philosophical/theological anthropology.②Xu, 2008

This shows how significant and sophisticated the literature-anthropology integration can be. Behind this interdisciplinarity lies an integrated cross-field research paradigm. This “two-become-one” subject represents traditional humanities and at the same time echoes classic natural sciences and contemporary social sciences. That is why literary anthropology can be regarded as a good example of a contemporary academic transformation.

4. Four issues: the internal constitution of literary anthropology

Combining literature and anthropology into an organic whole, literary anthropology concerns four issues, which respectively are the issue of literature,the issue of anthropology, the issue of literatureanthropology relations, as well as the issue of literary anthropology. The four issues are inter-related to and different from one another.

4.1 Issue of literature

In fact, this so-called “issue of literature” has already been mentioned above in discussing the translation of the word “l(fā)iterature” into Chinese,the introduction of this word to China as a modern Western concept, and its integration into Chinese language teaching. It is still necessary to have further discussions on this issue. For example, a BA or MA program of Chinese language usually includes the history of modern and contemporary Chinese literature, the history of ancient Chinese literature, and even the history of foreign literature(at some universities) covering the development of literature in the West, Japan, India, etc. Nowadays,this long-established system is faced with doubts and challenges, which can be summarized as the following two aspects.

First, there is a clear lack of ethnic diversity in Chinese literature. The existing written history of Chinese literature is largely restricted to the history of Han Chinese language literature and Han ethnic literature. From the Book of Songs to the works of Lu Xun, Chinese literature had been dominated by Han ethnic writers and filled with Han literary works composed from the perspective of the Central Plains.Such a lack of ethnic diversity prevents an objective and fair representation of the literary achievements of the other 55 ethnic minorities in China. This is indeed a serious issue.

Second, the definition of literature in the Chinese context is to a large extent restricted by the Western tradition. Owing to the restriction, literature is subdivided into four major forms, which are poetry,novels, essays and drama, and must be presented in printed version. Works not fulfilling the above requirements are excluded from the category of literature. This elite perspective, along with the written form requirement, strangles the development of living literary forms (folk form, oral form and rite form). Almost all oral epics, such as King Gesar,Manas, Liu Sanjie and Ashima, are without exception excluded from the orthodox system of literary classification. The best treatment they can expect is to be labeled as an independent category, which is either in binary opposition to the elite literature in writing or relieved against the former.

In this sense, China’s existing literary concepts,theories and history are far from sound and complete.As a subject, the so-called “wenxue” (literature) in modern Chinese, which in fact ambiguously means“study of literature,” is a knowledge about literature and therefore is quite problematic. To settle such a problem, the Chinese concept of literature must be enriched in an era of “hyper-texts” and online media that such texts are based on.

Given the diversity of the world today and the dynamics of human history, the extensively applied literature textbooks and corresponding value systems can no longer answer all literature-related questions.A possible solution is to orient towards anthropology.

4.2 Issue of anthropology

The ultimate question of anthropology lies in“what mankind is.” In a broader sense, anthropology also concerns the existence and changes of all mankind from ancient times until today. This subject needs to answer the question of “who we are,”“where we are from,” “where we are,” and “where we go” respectively proposed by ancient and modern Chinese (Han majority and ethnic minorities alike),Indian, American, etc.

King Gesar

In the West, answers to these questions had already been found prior to the formation of modern anthropology. Their answers were provided by the God in “creationism” and the Bible. Later, modern anthropology subverted such creationism-based answers by replacing “creationism” with “naturalistic evolutionism, substituting science for religion,and rewriting history with humanism. During this process, initiated and represented by Charles Darwin,anthropologists began to rewrite “human story”based on animal fossils and archaeological sites;following that, through gene mapping, they presented the “new epic” that all humans originated in Africa.Intentionally challenging the Bible, they renamed the protagonist of that “human story” as the “Real Eve”,instead of a woman made from Adam’s rib. Thus, all ethnicities from diverse cultural backgrounds and in different skin colors (including Chinese) across the world came from the same matrix of nature.①More information can be found in the documentary The Real Eve (ISRC:CNA510501270) made by American Discovery Communications, imported by China Wencai Audiovisual Publishing Company in 2005.

Advocating scientism, anthropologists’ new answers “transcended” those of the Bible in form and integrated the two major Western traditions of Hebrew and Greece. Even so, their answers failed to address other challenges from “axis discourses”in the non-Western world.②The above mentioned “axis discourses” are developed based on Karl Jaspers’s coined term “Axial Age” and Michel Foucault’s discourse theory.For example, these challenges can be found in the Taoist theory of “Yin-Yang and Five Elements” and the Buddhist theory of“Six Realms in the Wheel of Karma.”

Yin Yang and Five Elements

I hold that the Buddhist answers to the ultimate questions of mankind are not inferior to those in Bible stories. Take the interpretation of “Painting on the Six Realms of Existence” as an example.Extensive and profound, this interpretation touches upon a wide religious scope ranging from “greed,hatred and ignorance” of human nature, the “twelvelinked causal formula” that determines human destiny, and the recurring and unpredictable “six realms concerning life and death” to Nirvana. It gives a thorough and coherent analysis of human origin, circumstances and relationships with their surroundings. It is not compulsory for one to accept such an interpretation. Yet, as a religious discourse different from that of Christianity, it requires more attention and comparative studies.①Xu, 2011

Thus, anthropology is all about mankind. From an anthropological perspective, literature is also related to mankind and is reflected in different depictions and descriptions of “what mankind is.” The fact that anthropology needs to answer questions concerning both anthropology and literature creates the possibility of exploring the relevance between literature and anthropology.This forms an inevitable transition to literary anthropology.

4.3 Issue of literature-anthropology relation

This relation includes two different dimensions,both of which lead to the combining of literature with anthropology. As mentioned, this issue attempts to link the two academic areas or subjects. On one hand, anthropology helps to better understand literature. On the other hand, literature is applied to mirror anthropology. The combination of the two may give rise to the birth of a new interdisciplinary subject: literary anthropology.

Painting on the Six Realms of Existence

This literature-anthropology alliance brings about the following questions. What is its new focus?What are the research targets and methods? How should corresponding interdisciplinary studies be conducted? These questions lead to the fourth issue.

4.4 Issue of literary anthropology

Judging from the development context and practice of this new subject, literary anthropology,strictly speaking, is still at the stage of paradigm exploration so there is no need to prematurely define literary anthropology in a hurry. It is better to describe the existing practices, and to showcase the status quo and future prospects of literary anthropology through process analysis and case studies.

Below is a brief analysis of relevant Chinese scholars’ academic practice.

5. Inclusive class ification:exploration and practice of literary anthropology in contemporary China

The development of literary anthropology in China has witnessed several ups and downs. It can be divided into two stages: 1905-1949 and 1949-present.Characterized by fundamental achievements,the first stage required thorough review and summarization. This stage also saw the emergence of many prominent figures such as Wen Yiduo, Zheng Zhenduo and Mao Dun. Featured by reconstruction of the subject system, the marked achievements of the second stage mainly fall into five types or five domains of discourse.

5.1 Classics and reinterpretation

In the 1980s, with the introduction of Western“archetypal criticism” theory and the emergence of “root-seeking literature” in China’s Mainland, a book series entitled An Anthropological Explanation for Chinese Civilization was published. This book series contains a sequence of books, among which are A Cultural Interpretation on Chu-ci Poems by Xiao Bing, Explanation of Culture in the Book of Songs by Ye Shuxian and A Cultural Interpretation on Shuowen jiezi by Zang Kehe. Regarding the significance of this book series, its editor-inchief Wang Xiaolian commented,①Wang, 1995“(the authors)kept balance between the reference of traditional documents and the application of Western theories, based on which their own insights were developed”. Looking back, in terms of disciplinary development, this book series, along with its advocacy and practice of reinterpreting classics,marked the start of China’s literary anthropology in the new era. The major significance of this book series lies in its attempts to reinterpret traditional Chinese documents with anthropological vision and methods and to abandon such conventions as textual criticism and explanation in a philological approach.Of course, their conclusions are not necessarily recognized by Chinese academia; in fact, some have even triggered heated debates. Nevertheless,the reinterpretation does make way for thoughtprovoking discussions and even facilitate a new type of literary anthropology.

5.2 Archetypes and criticism

This practice applies anthropological theories and methods to the study of Chinese literary criticism. Since the late 1980s, a group of scholars,represented by Fang Keqiang and Ye Shuxian, have published multiple papers, applying the archetype theory to the analysis of Chinese literary works.Examples of these papers are “Archetype theme:Goddess worship in Dream of the Red Chamber”,“Prototype pattern: the puberty rite of Journey to the West” and “Prototype images in the classics of China”. In 1992, Mythology: Archetypal Criticism①Ye, 1987and Criticism of Literary Anthropology②Fang, 1992were successively published. The latter systematically summarized the anthropological criticism of literature. Its author Fang Keqiang later launched a course on this topic. Targeting MA students, this course covers“primitivism-based literary criticism,” “mythological archetype-based literary criticism,” “global trend of literary anthropological criticism,” etc. Through this course, Fang has introduced such practice of criticism to China’s public system of higher education and enhanced literary anthropology’s recognition and influence as an emerging subject in Chinese academia.

5.3 Literature and rites

In this new era, the integration and study of literature and rites has emerged as a new type of literary anthropology. A representative scholar in this regard is Peng Zhaorong at Xiamen University.In his early stage of comparative literature studies,Peng mainly focused on Greek drama. In an interdisciplinary approach integrating literature with anthropology, Peng analyzed the Dionysian and the rites mentioned in the Golden Bough, unveiling the ceremonial symbols behind this drama. Having returned to China as a visiting scholar in rite studies in 2004, Peng published a book on literature and rites based on the first-hand documents he had collected overseas. The subtitle of this book is “Literary anthropology from a cultural perspective”. Following in his steps, many scholars took part in the study and interpretation of rites in local literature.

Looking back, the focus on literature and rites should be a key achievement of the study of literary anthropology. After all, this domain of discourse relates literature with rites from a perspective of anthropology and, more importantly, regards literature as a collection of rites in theory. This is a significant contribution. What is special about literature and rites as a domain of discourse?For example, rite study is an important part of anthropology. For many people, rites are always associated with ancient, remote and rural customs,easily remind one of religious occasions or witchcraft, and have nothing to do with the secular and cosmopolitan life of today. This is a biased view.In fact, in the secular and cosmopolitan context of today, one can hardly avoid being encompassed by all our contemporary meaningful rites, ranging from opening ceremonies (school opening ceremony,national day ceremony, the Olympics opening ceremony, the World Expo opening ceremony, etc.)to award ceremonies. Each of these rites is worth detailed analysis and interpretations from a literary or anthropological perspective. No other case can better demonstrate the tight integration of literature and rites than a national flag-raising ceremony, which is performed daily across the world. This ceremony mainly consists of two parts, i.e. playing the national anthem and raising the national flag, accompanied with the literary form of lyrics. During a flag-raising ceremony, Chinese people stand facing the national flag and sing the solemn sacred national anthem,“Arise! Ye who refuse to be slaves!” On such an occasion, literature is thus exhibited in the form of a rite.

This domain of discourse relates literature with rites from the perspective of anthropology. More importantly, it regards literature as a collection of rites in theory. In human society, rites are everywhere.Even those living in the metropolises of today cannot escape being encompassed by rites.

Judging from the actual research progress, the literature-rites domain is still in the ascendant, for which more efforts are needed to free literature from textual limitations, enrich the existing monotonous classification patterns based on written words, and regard literature as a collection of rites (dynamic and interactive cultural phenomena in life scenarios).

5.4 Ballad and sinology

This domain attempts to rationalize “authorityscholar-public” structure and combine elite written literature with folk verbal arts into an organic whole.In this regard, I did some research and published a work entitled Ballads and Sinology. Many more similar achievements have been made by other scholars, who have published works such as Going to the People: Chinese Intellectuals and Folk Literature 1918-1937 and A Downward Revolution. Those attempts were supposed to review and interpret the literary expressions of a nation, folklore and customs from a macro-perspective. Relevant scholars are engaged in the study of “grand literature,”“l(fā)iving literature,” “grass-roots literature” and even “l(fā)ife literature” and “ultimate literature” in an anthropological sense.①Xu, 2008; Hung, 1993; Zhao, 1999

In addition, I also conducted field studies in the ethnic minority areas of Guizhou province and Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region and accordingly published the book Research on Folk Custom of Kgal Laox. The purpose of this book was in line with that of the above mentioned books.That is, within the framework of national discourse and a Sinological narrative, the book examines and interprets the literary expressions of a nation,its folklore and customs. Of course, literature here should be understood as “grand literature,” “l(fā)iving literature,” “grass-roots literature” or even “l(fā)ife literature” or “divine literature” in an anthropological sense. Examples in this regard are rare but can be found, including but not limited to Chao Gejin’s study of oral traditions of the ethnic minorities along the Silk Road, Luo Qingchun’s research and passingon of Yi ethnic literature, as well as the studies of the Zhuang ethnic folk song contests and Liu Sanjie’s oral epic made by Liang Zhao, Lu Xiaoqin, Liao Mingjun, etc.②Liang, 2007; Lu, 2005; Liao & Lu, 2011

5.5 Mythology and history

This domain sees mythology and history as an integrated whole and is arguably a pioneering extension of literary anthropology in the new era.Representative achievements in this regard are a few collections of related books compiled by a team led by Ye Shuxian.

In the context of “new-vernacular literature”promoted by the May 4th Movement in 1919, myths began to be included in the textbooks of literature.For example, there was mention of ancient Greek and Chinese myths, along with other myths and fairy tales of ethnic minorities from around the world. However, due to the excessive emphasis on the theory of evolution, myth interpretations have the associations of being “past,” “foreign,” “uncultured”and “outdated.” Now, with structure-functionism replacing evolutionism as the research paradigm,scholars in this field tend to study mythology from a perspective of cultural relativism and pluralism and have a more tolerant and inclusive understanding of mythology. Meanwhile, adhering to the so-called“new mythological view,” they attempt to further interpret ethnic memories, which concern ethnic literature, history and other aspects. In such a context,Ye Shuxian, proposed to reinterpret the “mythological China” in an integrated approach of literature and history. According to Ye Shuxian:

“Mythology, as the crystallization of human wisdom in primitive times, carries the DNA of a nation. The subject classification systems,which emerged later and covered literature,history and philosophy, have failed to include mythology in its entirety. As a form of sacred narration, mythology was in coexistence with prehistoric religious beliefs and rites. Together,they formed the common source of literature,history and philosophy. The early history of China is arguably a“history of mythology.”The integration of literary anthropology and historical anthropology is the right approach to the revival of traditional Chinese culture and the re-appreciation of the myth-history of China. Thus, this paper hereby calls for the shift of academic focus“Chinese mythology from a literary perspective”to“mythological China from an integrated cultural perspective.”①Ye, 2009

Furthermore, the study of mythology and history from a perspective of literary anthropology also involves a contrastive analysis of ancient texts and contemporary society. Corresponding research results have already been made, among which are some historians’ reviews of time-honored notions and phenomena on “descendants of Yan and the Yellow Emperor,” “Worship of the Yellow Emperor,”“hero ancestors,” and “story of brotherhood,”etc.②Shen, 1997; Sun, 2000; Wang, 2000Following the trend, heated debates over the representation of new myths (wolf totem, descendants of the dragon, etc.) in contemporary times are held among scholars and artists.③Jiang, 2004; Xu, 2006It can be concluded from these debates that Chinese mythology continues to this day and is represented by “overseas Chinese’s on-site worship of Yan and the Huang Emperor”and the building of “memorial halls in honor of Yan and the Huang Emperor and Warrior Chi-you” in provinces like He’nan and Guizhou.

As far as I am concerned, the analysis and interpretation of ancient mythology and history from an anthropological perspective is of great significance to the practice of literary anthropology in China.That is because such an analysis and interpretation concern a key matter, i.e. how to carry forward and evaluate the ethnic memory of China, which includes a diversity of written documents and oral heritage passed on from ancient times to this day.

The above mentioned types or domains of discourse indicate three orientations of literary anthropology in the academic practice in contemporary China. These three orientations are multi-text, multi-literature and multi-culture, which are all valued by relevant scholars. This paper holds that the core or basis of the three orientations can be summed up as a “matter of presentation”.

6. Conclusion

The historical development of literary anthropology in China can be defined by a list of figures, namely, one subject, two disciplines, three orientations, four issues and five domains.

“One subject” refers to the fact that literary anthropology is a subject, an approach, a field or an attempt, and at the same time it is also a new paradigm of knowledge introduced from the West and gradually developed in China.

“Two disciplines” refer to literature and anthropology, which are closely connected.

“Three orientations” refer to multi-texts,multi-literature and multi-culture, which must be simultaneously considered by scholars of literary anthropology. The common intent of the three lies in the building of a holistic literary view for the subject of anthropology.

“Four issues” refer to the issue of literature,the issue of anthropology, the issue of literatureanthropology relations, as well as the issue of literary anthropology. Integrated into an organic whole, the four issues form the basic research content of this paper.

“Five domains” refer to Chinese literary anthropology’s five representative domains of discourse and corresponding achievements made so far, ranging from “classics & interpretation,” through“archetypes & criticism” and “l(fā)iterature & rites,”to “ballad & sinology” and “mythology & history.”These five domains demonstrate the persistent pursuit of Chinese scholars, whose efforts have brought about successes and failures, both of which are worth reflection and review.

There will be variations. As time goes by, new topics and domains are sure to emerge. For example,in recent years, there are discussions on topics like“multi-evidence,” “intangible cultural heritage,”“ethnographic text,” “anthropological writing” and“ethnographic text,” all of which are worth further study.

As an emerging subject that concerns both liberal arts and sciences, literary anthropology is still in the early stage of development in China. For many more achievements in this regard, relevant scholars should work even harder and secure more support from like-minded scholars committed to an integrated,interdisciplinary research approach. The future of literary anthropology relies on the participation and reform of later generations, as well as the sustained endeavor of previous and current scholars.

Contemporary Social Sciences2018年5期

Contemporary Social Sciences2018年5期

- Contemporary Social Sciences的其它文章

- Cultural Structure of Solar Terms and Traditional Festivals

- The Development of China’s Intellectual Property Law over the Past Forty Years of Reform and Opening Up

- The Evolution, Characteristics of Poverty and the Innovative Approaches to Poverty Alleviation

- Balance and Sharing: Women’s Childcare Time and Family’s Help

- Social Security Internationalization During China’s Reform and Opening Up from 1978 to 2018— Viewed from the Paradigm of a Community with a Shared Future for Mankind

- Pattern of Opening Up, Integration and Reshaping Economic Geography—A New Economic Geography Analysis of the Belt and Road Initiative and the Yangtze River Economic Belt