Improve access to the EU market by identifying French consumer preference for fresh fruit from China

WANG Er-peng, Zhifeng Gao , Yan Heng

1 School of Economics and Management, Nanjing Tech University, Nanjing 211800, P.R.China

2 College of Economics and Management, Jilin Agricultural University, Changchun 130118, P.R.China

3 Food and Resource Economics Department, University of Florida, Gainsville, FL 32606, USA

1. Introduction

From 2005 to 2014, fruit production in China increased from 161 million to 261 million tons (NBSC 2015). At the same time, fresh fruit exports have increasingly played an important role in generating income for rural households in China. Fresh fruit exports increased significantly from 147 954 tons in 2002 to 342 297 tons in 2013 (FAO 2013).In general, Chinese growers heavily rely on pesticides and chemical fertilizers, and there is a high occurrence of residues in fruits and vegetables (Hamburger 2002; Chenet al. 2011). These practices have resulted in a significant increase in yield and total output, while at the same time may impair food safety (Nieet al. 2005; Haoet al. 2015).A variety of recent food safety scandals not only affects Chinese consumers’ confidence in the food safety and quality of domestically produced products but also damages the image of Chinese food products globally (Ortegaet al.2011; Guo and Wu 2014).

In the meanwhile, the mandatory country-of-origin labeling(COOL) requirement in many economically developed countries makes selling Chinese food products in the global market even more challenging. Under the mandatory COOL requirement, retailers must provide information about the country where a product is produced. In 2009, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) required retailers to provide information regarding the country-of-origin (COO)of selected products (USDA 2009). In the EU, COOL has been mandatory for honey, fruit and vegetables, olive oil,fishery and aquaculture products, and beef around the 2000s. The EU further extended the mandatory COOL rules for meat other than beef in 2014 (USDA 2014).

These developments in mandatory COOL occurred concurrently with an increasing realization in the Chinese food industry that competing on price alone is not the most attractive business strategy. To develop more effective strategies to promote Chinese agricultural products in the global market, growers and fresh fruit exporters in China need a better understanding of consumers’ perceptions and preferences for Chinese fresh fruit. In addition, identifying the factors that affect the likelihood of purchases and heterogeneous preferences of Chinese fresh fruit in the global market are crucial for fresh fruit exporters in China to design appropriate market promotion and segmentation programs.

The objective of this article is to identify the French consumers’ perception and preferences of fresh fruit from China. Particularly, we will examine French consumers’safety and quality perceptions for fresh fruit from China;estimate French consumer preferences for Chinese fresh fruit; identify the important factors influencing French consumers’ likelihood to purchase Chinese fresh fruit, especially grapefruit and pomelo; and determine heterogeneous consumer preferences. Because most economically developing countries rely heavily on agricultural export to generate foreign currency, results of this paper will provide critical information to both China and other economically developing countries in their efforts to improve market penetration in economically developed countries.

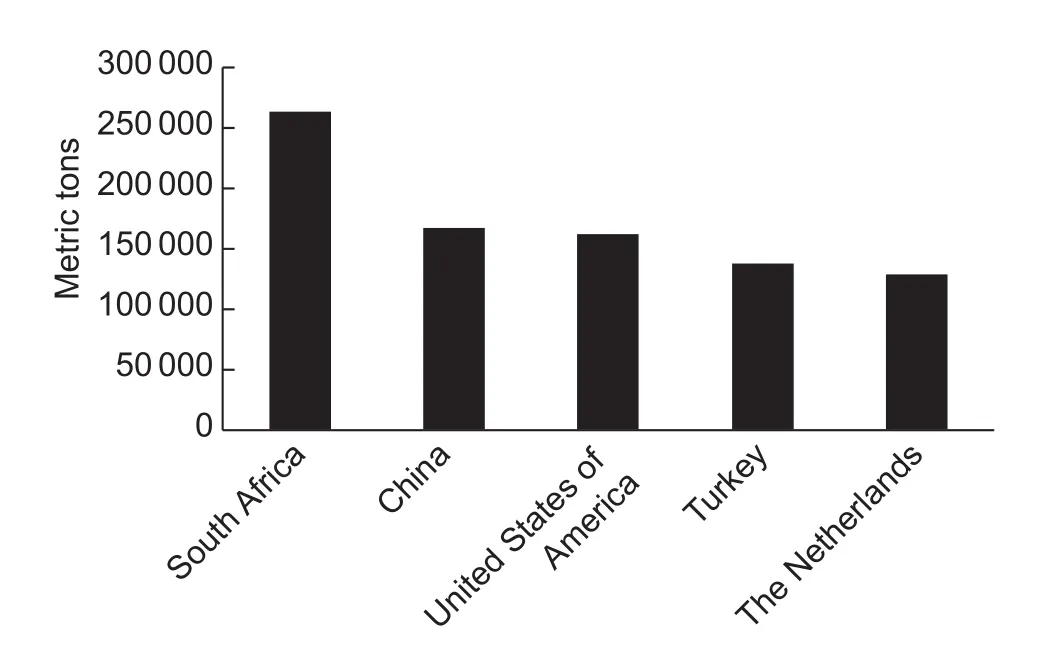

The world market of fresh fruit, especially that of fresh citrus (e.g., grapefruit/pomelo), is both important for China and French. China is one of the world’s largest citrus producers. From 2005 to 2015, citrus production in China increased by more than 128%, from 15 million to 35 million tons. Also, China is the second top exporter (166 782 metric tons in 2013) of grapefruit/pomelo after South Africa (FAO 2013) (Fig. 1), and exports of grapefruit/pomelo increased from 11 606 metric tons in 2002 to 166 782 metric tons in 2013. China is also a major supplier of fresh citrus and the most significant exporter of pomelo to the EU (EUC 2012;CBI 2016). Among the EU, France is the second largest grapefruit importer among the EU-27 countries. The total fresh grapefruit import of France was 85 013 tons, equivalent to 83.41 million US dollars in 2013 (GTA 2017). In 2013, the Chinese grapefruit accounted for about 8% of France’s fresh grapefruit import, ranked number five after South Africa, the United States, Spain, Israel, and Mexico. Most importantly France is one of the largest and the most important importers of Chinese pomelo in the EU countries (GTIS 2016). From 2010 to 2017, France imported 6 783 metric tons pomelo from China, ranked as the 6th largest export market in the EU of Chinese pomelo (GTA 2017). Therefore, determining French consumer preference for Chinese fresh fruit and grapefruit and pomelo would provide critical information for Chinese agricultural industry to expand the market in France as well as other countries in the EU.

Fig. 1 Grapefruit (inc. pomelos) exports of top five exporters.

2. Literature review

For fruits and vegetables, freshness, taste, and aroma are the most important attributes consumers take into account(Mooret al. 2014). As examples, Houseet al. (2011) and Gaoet al. (2011) found that sweetness, shape, acidity, and flavor are the most important factors influencing consumers’willingness to buy mandarins. Bruhn (1995) identified firmness and external color of peaches as the most important attributes for consumers to judge the internal quality of fruit.Miglioreet al. (2015) showed that the quality attributes such as color, number of seeds, and ease of peeling are more important for cactus pear fruit.

Other than sensory attributes, credence attributes also play an important role in consumers’ fruit and vegetable consumption. Studies conducted in various countries have found that credence attributes, such as price, origin,production methods, and quality indicators, are essential drivers of fruit purchases (Campbellet al. 2013; Mooret al. 2014; Miglioreet al. 2015). Among all the credence attributes, COO is one of the most important attributes of food products (Caswell 1998; Yuet al. 2016). Researches have shown that consumers are willing to pay a price premium for COO that is associated with healthier and safer foods (Yiridoeet al. 2005; Batteet al. 2007; Gao and Schroeder 2009). Consumers in economically developed countries are willing to pay a premium price for domestic agricultural products because of the perceived high quality of the food products from their own country (Verlegh and Steenkamp 1999; Loureiro and Umberger 2003; Gao and Schroeder 2009; Petersonet al. 2013). Growers and ranchers in economically developed countries have supported COOL because they regard it as a non-tariff trade barrier that can potentially provide producers with a competitive advantage in domestic markets (Carter and Zwane 2003; Umberger 2004).

However, COOL might be a challenge for economically developing countries that are more likely to rely on the agricultural exports to increase rural income. This is because there seems a positive relationship between product evaluations and degree of economic development(Schooler 1965; Krishnakumar 1974; Hampton 1977; Wang and Lamb 1983). For example, food from an economically developed country such as the Netherlands may be perceived to be of higher quality than similar food from a less economically developed country (Juric and Worsley 1998). Xieet al. (2015) show that US consumers are willing to pay a significantly lower price for fresh broccoli from China even when the products carry USDA certified organic labels.

In general, agricultural export of economically developing countries is very important for their foreign income earnings. Therefore, determining consumers’ attitudes and preferences in economically developed countries for agricultural products from economically developing countries is critical for growers and exporters in economically developing countries to improve marketing strategies and access to the global market. As most studies focused on consumer preferences for domestic agricultural products in economically developed countries, this paper aims to fill this gap by using France and China as examples to examine how consumers in an economically developed economy perceive and prefer agricultural products from an economically developing economy.

3. Methods and data

3.1. Consumer survey and data collection

Toluna USA, Inc., an international survey company, helped distribute our survey online to its national representative consumer panels in France. To qualify for the survey,respondents had to be 18 years old or older; the primary shopper of the household; and a consumer of fresh citrus.To improve the data quality, we identified the respondents who may not carefully read the survey questions by using the “trap question” method (Gaoet al. 2015, 2016; Joneset al. 2015). Removing respondents who fail the “trap questions” and those with any missing responses resulted in 533 observations for final analysis. The sample size is more than the requirement (384) for a population of one billion, with ±5% marginal errors and 95% confidence interval(Dillmanet al. 2014). In the survey, we measured consumer perceptions of fresh fruit from China, the importance of fresh citrus fruit attributes, and the stated likelihood of purchasing Chinese fresh fruit based on consumer demographics such as gender, age, income, etc. Table 1 defines all the variables used in the analysis.

The importance of fresh citrus attributes was measured by asking respondents to rate the importance of citrus characteristics in their fresh fruit purchase decisions. These attributes include intrinsic attributes, such as Freshness,Flavor, Appearance, Juiciness, Fruit Size, Ease of Peeling,and Seeds (number of seeds in fruit), and extrinsic attributes,such as Price, Package, Brand, and COOL. The stated likelihood of consumers’ willingness to buy Chinese fresh fruit, grapefruit, and pomelo was measured on a five-point Likert scale using a series of questions such as1Cronbach’s alpha of the stated likelihood of consumers’ willingness to buy Chinese fresh fruit, grapefruit, and pomelo is 0.87, which is significantly higher than the recommended value of 0.70 (DeVellis 2012).:

(1) If the price is the same, how likely would you buy fresh fruit from China?

(2) Assuming the price is the same, please indicate the likelihood of your willingness to buy grapefruit from China.

(3) Assuming the price is the same, please indicate the likelihood of your willingness to buy pomelo from China.

3.2. Research methods: Ordered logit and latent class models

To determine the factors that affect consumer preference for Chinese fruit and identify consumer heterogeneous preferences, ordered logit models and a latent class model are used in the econometric analysis.

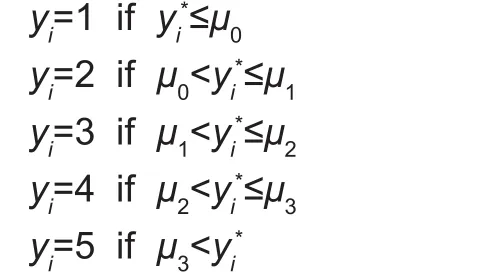

The ordered logit modelAn ordered logit model is used to determine the important factors affecting the likelihood for French consumers to purchase fresh fruit, grapefruit,and pomelo from China based on an ordinal ranking in five categories using the following specification:

Where,Direpresents a vector of demographic variables,such as age, income, education, marital status, and gender;Iipresents a vector of preference variables, including the importance rating of price, freshness, flavor, etc.; andPirepresents a vector of perception variables such as risk and quality perception of fresh fruit from China.εiis the disturbance term. Becauseyi*is unobserved, representing consumers’ true likelihood of willingness to buy fresh fruit from China, we do observe that:

TheμSare unknown threshold parameters to be estimated withβsin eq. (1).

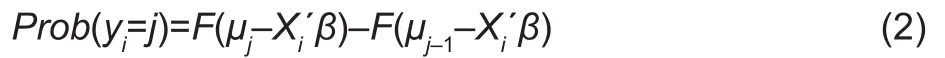

The probability that consumeriwill select a specific responsejis given by:

Where,Fis a cumulative standard logistic distribution.

The same model is also estimated for consumers’probabilities of buying fresh fruit, grapefruit, and pomelo from China.

The latent class modelTo capture the heterogeneity, a latent class model (LCM) was used to cluster consumers into different groups based on key demographic variables.This method substantially outperforms other cluster methods such as thek-means technique, and it provides more formal criteria for the decision of the number of clusters (Magidson and Vermunt 2002; Chenet al. 2016). The underlying theory of the LCM is that individual behavior depends on observable attributes and unobserved factors that vary by latent heterogeneity (Greeneet al. 2003). Several information criteria such as Bayesian information criterion(BIC), adjusted BIC, and Akaike information criterion (AIC)can be used to determine the optimal number of classes

and the variables included in the final analysis (lower valuesrepresent better fit) (Miller-Graffet al. 2015).

Table 1 The definitions and statistics of all variables

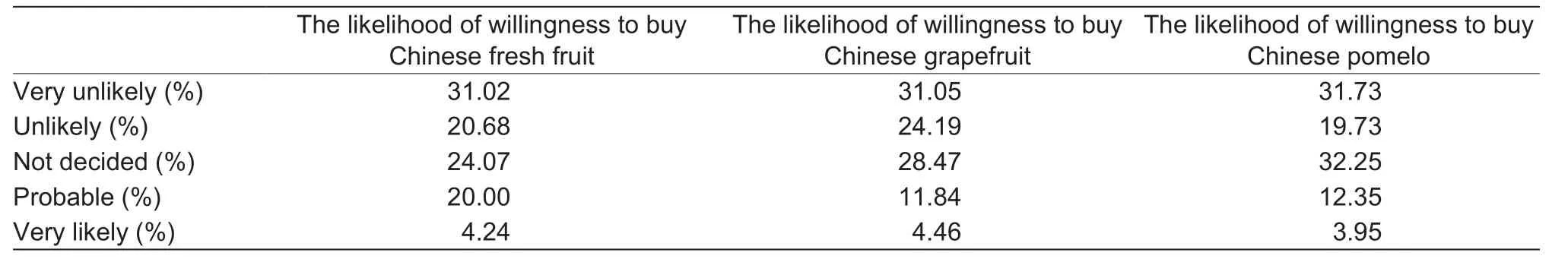

Table 2 Likelihood of consumer willingness to buy fresh grapefruit and pomelo from China

4. Results

4.1. Summary statistics

We used Stata12.0 to obtain the statistics of the variables.Overall, the average age of respondents was the same as the 2011 French national median age. Our sample has 64.7% female which was much higher than the 51.7% of the general population; this is reasonable because respondents needed to be the primary shopper of their household.Median household income of our sample was 26 993 Euros which was slightly higher than the French national median household income of 20 071 Euros in 2010 (Table 1). This may because that our survey was distributed online. Overall,the survey sample reflects the general characteristics of French households.

Results show that 89.49% respondents often ate grapefruit before and 48.78% of the respondents often ate pomelo before; 65.67% of the respondents had bought grapefruit/pomelo in the last year before the survey; and 27.02% of the respondents had eaten or heard of pomelo from China (Table 1). Table 2 shows that more than 50%of the respondents were very unlikely or unlikely to buy Chinese fresh fruit. As for fresh grapefruit and pomelo,the results are similar. This is consistent with the study by Ehmkeet al. (2008) on French consumer preferences for white onions; they found that there is a clear preference for domesticvs. imported white onions. French consumers also place great importance on the country-of-origin when they choose olive oil (Dekhiliet al. 2011).

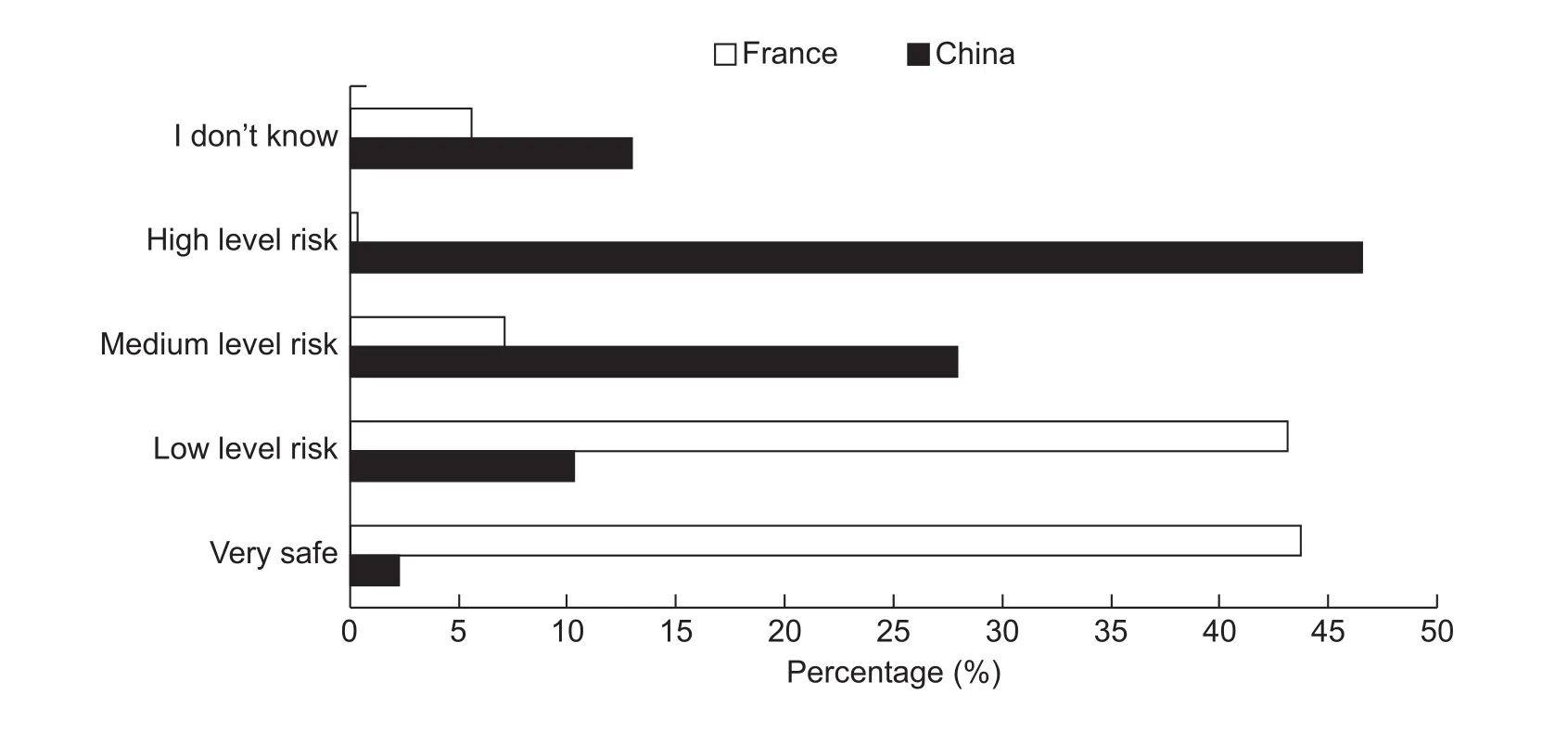

Fig. 2 demonstrates the potential reasons for French consumers’ unwillingness to purchase fresh produce from China. It shows that about 46.5 and 28.0% of the respondents considered fresh fruit from China to have a high-level risk and medium-level risk, respectively. Only 12.6% of the respondents thought fresh fruit from China had a low-level risk or was very safe. In the meanwhile, about 43.7 and 43.2% of respondents rated fresh fruit from French as low-level risk or was very safe. The result is consistent with studies on consumer preferences for COOL as the most frequently stated motivation for preferring domestic food products was food safety (Ehmkeet al. 2008; Lagerkvistet al. 2014; Mooret al. 2014).

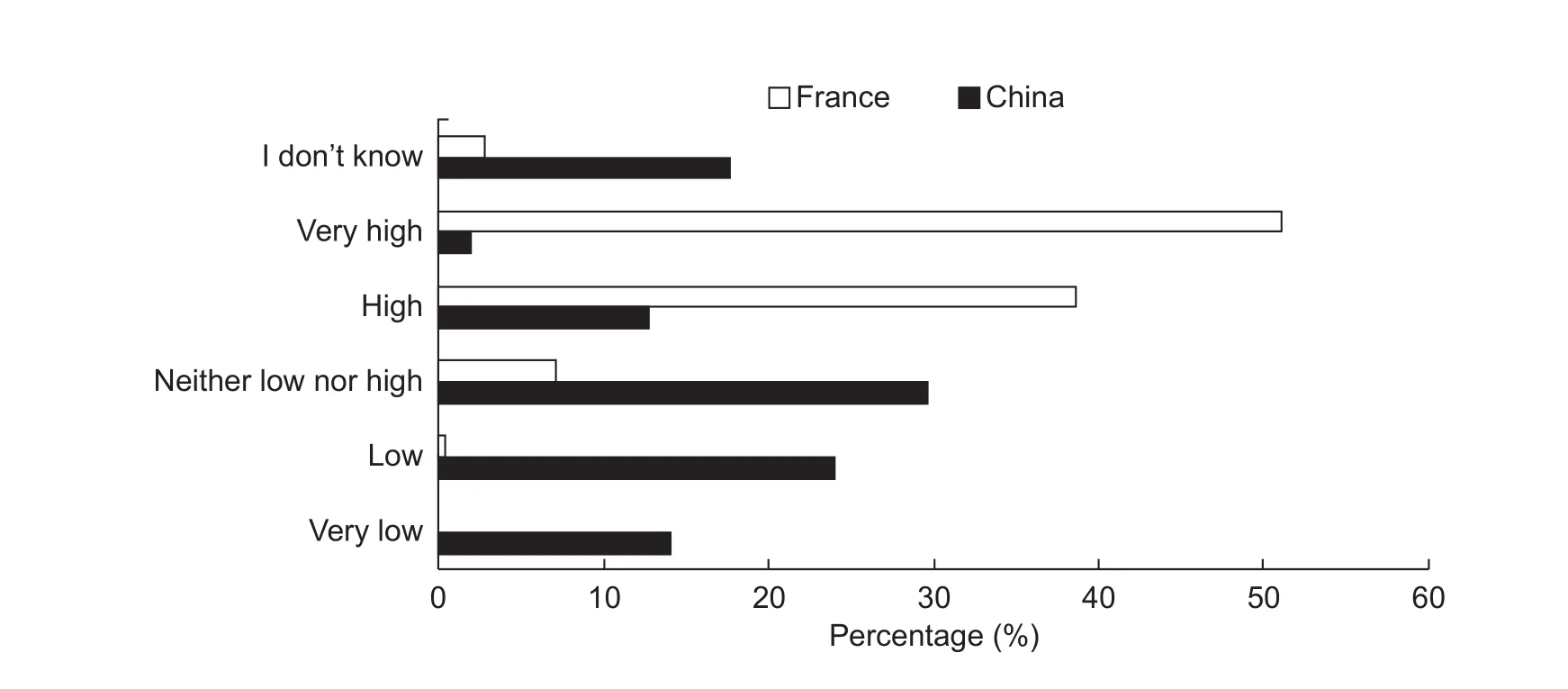

Consumers’ unwillingness to purchase fresh fruit from China can be further explained by the perceived low quality of fresh fruit from China. Fig. 3 shows that about 3 and 17% of the respondents didn’t know the quality of fresh fruit from France and China, respectively. About 38.1%of the respondents thought that fresh fruit from China had very low or low quality, and only 14.6% of the respondents believed that fresh fruit from China had very high or high quality. In the meanwhile, about 38.7 and 51.0% of the respondents considered French fresh fruit to have very high or high quality. Fig. 3 also shows that approximately 47.3%of the respondents thought that fresh fruit from China had average quality or had no opinion on their quality. This result indicates that there may be rooms to improve the quality perception of Chinese fresh fruit among French consumers.

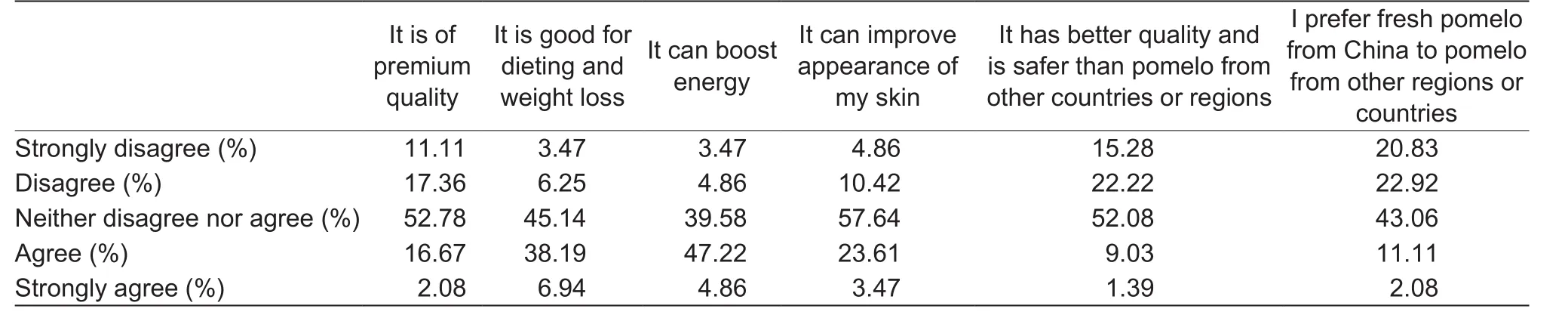

Table 3 reports the statistics of French consumers’perception of the quality of Chinese fresh pomelo (because there is no Chinese grapefruit in the French market, we only asked French consumers’ quality perception of Chinese pomelo). More than 43% of the respondents disagreed with the statement “I prefer fresh pomelo from China to pomelo from other regions or countries.” More than 28%of the respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement that fresh pomelo from China had premium quality. More than 37% of the respondents disagreed that Chinese fresh pomelo had better quality and was safer to eat than pomelo from other countries or regions. Results also show that 45% of the respondents considered fresh pomelo from China to be good for dieting and weight loss.And more than 52% of the respondents agreed with the statement that eating fresh pomelo from China could boost energy. These results imply that there are some market opportunities for Chinese pomelo if the product is promoted appropriately focusing on the health or functionality of pomelo.

4.2. Factors influencing willingness to buy fresh fruit from China

Fig. 2 French consumer risk perception of fresh fruit from China and France.

Fig. 3 French consumer quality perception of fresh fruit for China and France.

Table 3 French consumer agreement with the statements about Chinese pomelo

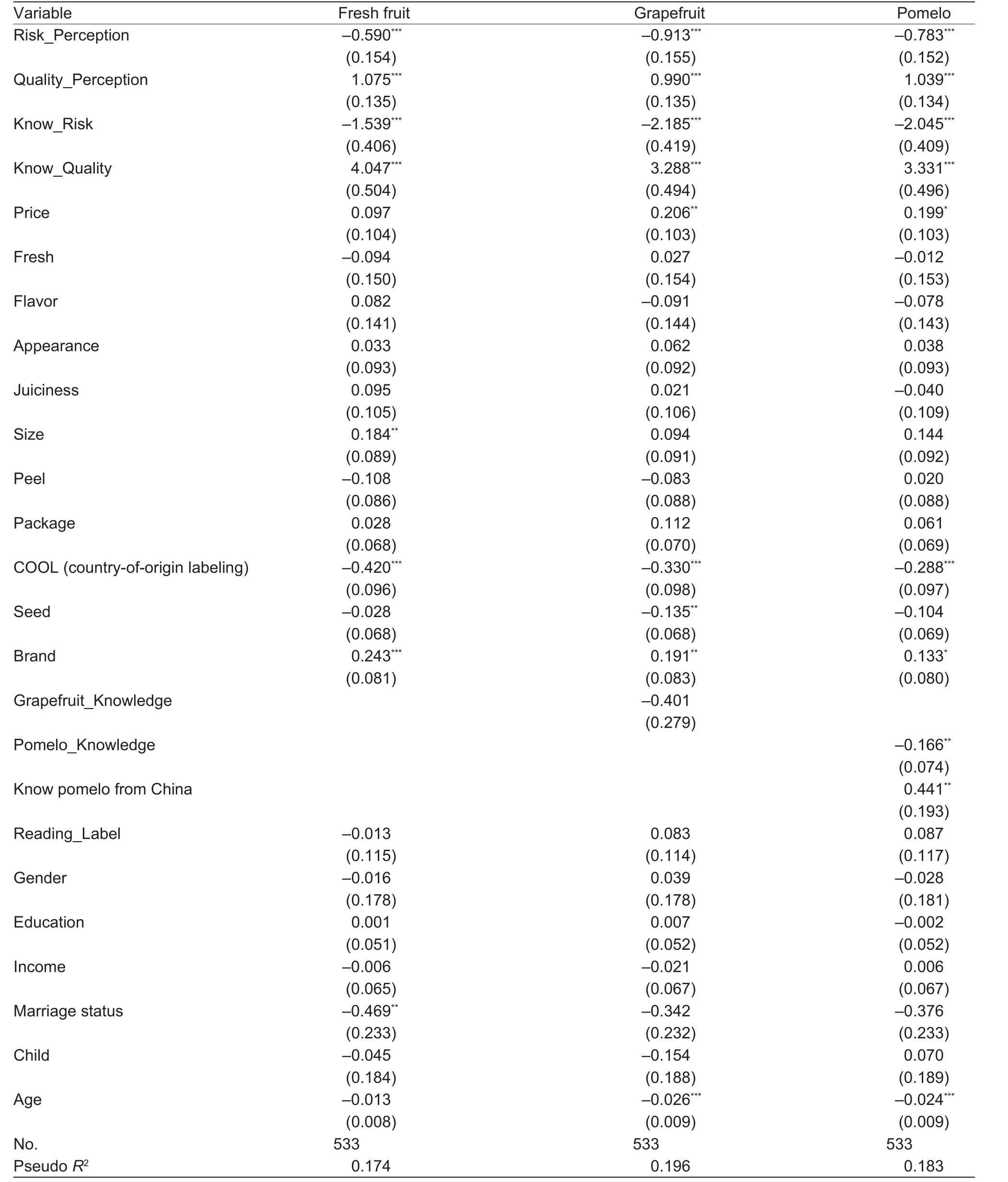

Results from the ordered logit modelResults of ordered logit models for fresh fruit, grapefruit, and pomelo are presented in Table 4. The independent variables forall models included demographic variables such as age,income, education, marital status, and gender; preference variables such as the importance rating of price, freshness,flavor, etc.; and perception variables such as risk and quality perception of fresh fruit from China. Four perception variables Know_Risk, Know_Quality, Risk_Perception, and Quality_Perception were included in the models. Know_Risk and Know_Quality indicated whether a respondent had any risk and quality perception, respectively for Chinese fresh fruit. Risk_Perception and Quality_Perception indicated a respondent’s level of food safety risk and quality perception,respectively, of Chinese fresh fruit.

The results show that among perception variables,risk and quality perceptions have a significant impact on consumers’ likelihood to buy Chinese fresh fruit, grapefruit,and pomelo. Compared to respondents who were unsure about the risk level of Chinese fresh fruit, respondents who did perceive a risk were less likely to buy Chinese fresh fruit,grapefruit, and pomelo. Respondents who perceived an overall quality of Chinese fresh fruit were more likely to buy Chinese fresh fruit, grapefruit, and pomelo than those who

were unsure about the overall quality of Chinese fresh fruit.Besides, consumers who had a high risk or a low-quality perception of Chinese fresh fruit were less likely to purchase Chinese fresh fruit, grapefruit, and pomelo.

Table 4 Parameter estimates for ordered logit models

From the view of economic significance, the results also show that the effect of quality perception is more significant than that of risk perception. Consumers who reported some levels of perceived risk of Chinese fresh fruit would have a significantly lower probability of stated “Unlikely” or“Very Unlikely” to purchase Chinese fresh fruit by 16.7%;while those who reported some levels of perceived quality of Chinese fresh fruit would have a significantly higher probability of stated “Likely” or “Very likely” to purchase Chinese fresh fruit by 55.4% (Appendix A). The same conclusions can be drawn to the likelihood to purchase of Chinese pomelo and grapefruit (Appendices B and C).These results indicate increasing the knowledge of the quality of Chinese fruit would increase consumers’ likelihood of purchase of Chinese fresh fruit. And improved quality perception has more effect on consumers’ purchasing intent than improved risk perception (consider fresh fruit from China less risky to consume).

Results also show that respondents who considered COO as an important attribute were more unlikely to buy Chinese fresh fruit, grapefruit, and pomelo. In the opposite,respondents who cared brand were more likely to buy Chinese fresh fruit, grapefruit, and pomelo. Respondents who cared about fruit size were more likely to buy Chinese fresh fruit, but not for grapefruit and pomelo. Respondents who cared about seeds in fruit were less likely to buy grapefruit, but not fresh fruit and pomelo from China.Interestingly, respondents who had more knowledge about pomelo were more likely to buy Chinese pomelo,while knowledge about grapefruit had no impact on their purchases of Chinese grapefruit. Experience with Chinese pomelo also significantly increased the purchase intent of Chinese pomelo. Most demographic variables had no statistically significant impact on consumer likelihood to purchase, except that single respondents were less likely to purchase Chinese fresh fruit, and older respondents were less likely to purchase Chinese grapefruit and pomelo. This is consistent with past studies that consumer demographics are commonly believed to be poorly related to consumer behavior and preference (Franket al. 2001; Johns and Gyimothy 2002). Psychological factors such as attitudes,beliefs, and personality characteristics are important factors influencing consumers’ purchase decision (Roberts 1996;Robinson and Smith 2002).

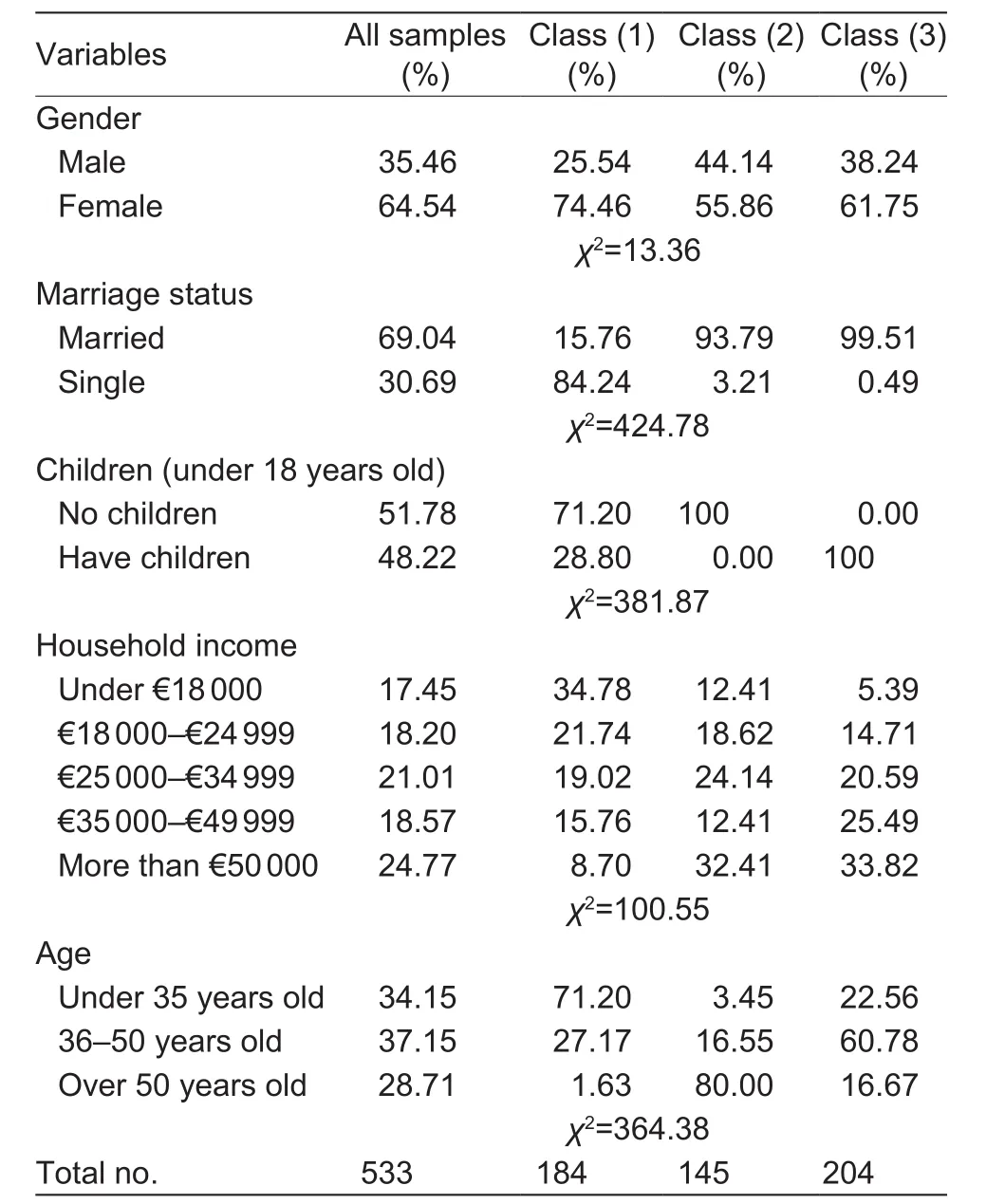

Result from the latent class modelWe used gender, age,marriage status, children in the household, and household income as the class determinants (we did not include education as a class determinant because the values of AIC, BIC and adjusted-BIC increase dramatically if including education variable). After comparing the information criteria in Table 5, we segment the whole sample into the three classes. Class (1), (2), and (3) included 34.5, 27.2, and 38.3% of the sample, respectively.

We tested for demographic differences across classes using chi-squared test and rejected the null hypothesis that demographics across three classes are the same.Therefore, the demographic differences across three classes are significant. Table 6 shows that class (1) had more respondents who were young, female, single, and without children. More than half of the respondents had a household income less than EU€24 999. Class (2) had relatively more respondents who were male, married, and without children. More than 80% of the respondents inclass (2) were 50 years or older and had relatively higher income than respondents in class (1). Finally, most of the respondents in class (3) were between 36 and 50 years old,married, and had at least one child. This class had a higher income than the other two classes.

Table 5 Information criteria used in determining number of classes in the latent class model

Table 6 Statistics of consumer profiles by segment

Regression results in Table 7 show that in all the three classes, respondents who cared about COO were unlikely to buy Chinese fresh fruit, and both risk perception and quality perception had a significant impact on consumers’ purchase decisions. Based on the coefficients in the regression models for the three classes2Statistical test of the difference in the parameter estimates between classes are reported in Appendix D., we can define class (1) as the less quality sensitivity consumer group because the coefficients of overall quality perception and Know_Quality are significantly smaller than those in the other classes. Class (2) can be identified as the brand and size concerned consumer group because in this class the respondents who cared about price,brand, and size were more likely to buy Chinese fresh fruit than those in other classes. Class (3) can be defined as the juiciness and package concerned consumer groupand it had the largest number of respondents, accounting for 38.3% of the sample. In this class, the respondents who cared about juiciness and package of fresh fruit were more likely to buy Chinese fresh fruit.

5. Discussion

Fresh fruit exports play an important role in generating revenue for Chinese agricultural industry, especially with the increasing amount of fresh fruit production and exports in China. However, the most recent food safety incidences damaged the image of Chinese-produced food products both domestically and globally. To keep Chinese freshfruit exports competitive in the world market, there is a critical need for a better understanding of foreign consumer attitudes and preferences for Chinese fresh fruit.

Table 7 Parameter estimates for latent class model

Using an online survey of French consumers, our study shows that the likelihood of French consumers’ willingness to buy fresh products from China is relatively low because of perceived high risk and low quality of fresh fruit from China.Regression results show that risk perception and quality perception have significate impact on consumers’ purchases of Chinese fresh fruit. French consumers who cared about COO were less likely to buy Chinese fresh fruit. Such findings are consistent with previous studies that consumers prefer domestically produced fresh produce over imports and the most frequently stated motivation for purchasing domestic products was food safety (Gaoet al. 2014; Mooret al. 2014; Xieet al. 2015). However, consumers who care about brand were more likely to select Chinese fresh fruit, grapefruit, and pomelo. And preferences for fresh fruit attributes are fruit specific. The results of latent class models obtained with key consumer demographics show that heterogeneity in preferences exists between different consumer groups. Fresh fruit juiciness and packaging have a more influential impact on French consumers’ purchases of Chinese fruit among those who were middle-aged (36 to 50 years old), married, parents.

6. Conclusion

Results in this study provide critical policy implications to China and other economically developing countries in their efforts to improve market penetration in economically developed countries. Firstly, suppliers from economically developing countries should keep improving their food safety and quality to enhance the quality and safety perception of their products in the world market. The marketing strategy may focus on health benefits to promote Chinese fresh fruit.Secondly, building premium brands and enhancing brand loyalty might be able to alleviate the adverse effect from COOL. Thirdly, marketing strategies should be customized to different consumer groups and Chinese fruit growers should enhance the specific fruit qualities preferred by the target consumer groups.

One of the limitations of the study is that consumer preferences are estimated in a hypothetical situation and there always remains the question of whether consumers would make the same choices in a real purchase situation.Research could also estimate consumers’ willingness to pay so that consumer preferences for Chinese fresh products could be quantified in monetary values. Because few studies have focused on food imports from economically developing economies, more studies to investigate consumer preferences for food imports from developing economies in different markets are needed. Future research could also compare the Chinese agricultural products with those from other countries to testify the factors that influence the consumers’ attitude or choice in France.

Acknowledgements

This work is/was supported by the USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) (Hatch project FLA-FRE-005292).Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the NIFA or the USDA.This research is also supported by the China Scholarship Council, the Humanities and Social Science Fund of the Ministry of Education of China (13YJC790138), the Jiangsu University Philosophy and Social Science Fund, China(2017SJB0191).

Appendicesassociated with this paper can be available on http://www.ChinaAgriSci.com/V2/En/appendix.htm

Batte M T, Hooker N H, Haab T C , Beaverson J. 2007. Putting their money where their mouths are: Consumer willingness to pay for multi-ingredient, processed organic food products.Food Policy,32, 145–159.

Bruhn C M. 1995. Consumer and retailer satisfaction with the quality and size of California peaches and nectarines.Journal of Food Quality,18, 241–256.

Campbell B L, Mhlanga S, Lesschaeve I. 2013. Consumer preferences for peach attributes: Market segmentation analysis and implications for new marketing strategies.Agricultural and Resource Economics Review,42, 518–541.

Carter C A, Zwane A P. 2003.Not so Cool?Economic Implications of Mandatory Country-of-Origin Labeling.[2017-02-15]. https://s.giannini.ucop.edu/uploads/giannini_public/b4/31/b4317373-e1d0-4de3-8a3c-5ab5e3e55421/v6n5_2.pdf

Caswell J. 1998. How labeling of safety and process attributes affects markets for food.Agricultural and Resource Economics Review,27, 151–158.

CBI (The Centre for the Promotion of Imports from Developing Countries). 2016. CBI product factsheet: Fresh pomelo in Europe. [2016-11-03]. https://www.cbi.eu/sites/default/files/market_information/researches/product-factsheet-europefresh-pomelo-2016_final_approved.pdf

Chen C, Qian Y, Chen Q, Tao C, Li C, Li Y. 2011. Evaluation of pesticide residues in fruits and vegetables from Xiamen,China.Food Control,22, 1114–1120.

Chen X, Gao Z, House L A, Ge J, Zong C, Gmitter F. 2016.Opportunities for western food products in China: The case of orange juice demand.Agribusiness,32, 343–362.

Dekhili S, Sirieix L, Cohen E. 2011. How consumers choose olive oil: The importance of origin cues.Food Quality and Preference,22, 757–762.

DeVellis R F. 2016.Scale Development: Theory and Applications.vol. 26. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks,California, USA.

Dillman D A, Smyth J D, Christian L M. 2014.Internet,Phone,Mail,and Mixed-Mode Surveys:The Tailored Design Method. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, New Jersey, USA.

EC (European Commission). 2012. Monitoring agri-trade policy:The EU and major world players in fruit and vegetable trade.[2016-08-26]. http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/trade-analysis/map/2012-2_en.pdf

Ehmke M D, Lusk J L, Tyner W. 2008. Measuring the relative importance of preferences for country of origin in China, France, Niger, and the United States.Agricultural Economics,38, 277–285.

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations).2017. FAOSTAT, Crop and livestock products. [2016-03-01]. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/TP

Frank C A, Nelson R G, Simonne E H, Behe B K, Simonne A H.2001. Consumer preferences for color, price, and vitamin C content of bell peppers.HortScience,36, 795–800.

Gao Z, House L A, Bi X. 2016. Impact of satisficing behavior in online surveys on consumer preference and welfare estimates.Food Policy,64, 26–36.

Gao Z, House L A, Gmitter Jr F G, Valim M F, Plotto A, Baldwin E A. 2011. Consumer preferences for fresh citrus: Impacts of demographic and behavioral characteristics.International Food and Agribusiness Management Review,14, 23–40.

Gao Z, House L A, Xie J. 2015. Online survey data quality and its implication for willingness-to-pay: A cross-country comparison.Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics/Revue Canadienne D’agroeconomie,64, 199–221.

Gao Z, Schroeder T C. 2009. Effects of label information on consumer willingness-to-pay for food attributes.American Journal of Agricultural Economics,91, 795–809.

Gao Z, Wong S, House L A, Spreen T H. 2014. French consumer perception, preference of, and willingness to pay for fresh fruit based on country of origin.British Food Journal,116, 805–820.

Greene W H. 2003.Econometric Analysis. Pearson Education,India.

GTA (Global Trade Atlas). 2017 Global import/export commodity trade data. IHS Markit Inc. [2018-05-01]. https://www.gtis.com/gta/

GTIS (Global Trade Information Services). 2016. World trade atlas. [2016-11-03]. http://www.tradestatistics.com/product.cfm?level=2&type=W&product=E

Guo J, Wu L. 2014. Trade effect analysis of food safety standards: The example of China’s agricultural exports.Agricultural Outlook,11, 69–74. (in Chinese)

Hamburger J. 2002. Pesticides in China: A growing threat to food safety, public health, and the environment.China Environment Series,5, 29–44.

Hampton G M. 1977. Perceived risk in buying products made abroad by American firms.Journal of Academy of Marketing Science,5, 45–88.

Hao B, Qin S, Wang X. 2015. Shanxi fruit producing apples,pears, peaches and jujube fruit pesticide residue levels and evaluation.Shanxi Agricultural Science,43, 452–455.(in Chinese)

House L A, Gao Z, Spreen T H, Gmitter F G, Valim M F, Plotto A, Baldwin E A. 2011. Consumer preference for mandarins:Implications of a sensory analysis.Agribusiness,27,450–464.

Johns N, Gyimóthy S. 2002. Market segmentation and the prediction of tourist behavior: The case of Bornholm,Denmark.Journal of Travel Research,40, 316–327.

Jones M S, House L A, Gao Z. 2015. Respondent screening and revealed preference axioms: Testing quarantining methods for enhanced data quality in web panel surveys.Public Opinion Quarterly,79, 687–709.

Juric B, Worsley A. 1998. Consumers’ attitudes towards imported food products 1.Food Quality & Preference,9,431–441.

Krishnakumar P. 1974. An exploratory study of the influence of country of origin on the product images of persons from selected countries. Ph D thesis, University of Florida, USA.

Lagerkvist C J, Berthelsen T, Sundstr?m K, Johansson H.2014. Country of origin or EU/non-EU labelling of beef?Comparing structural reliability and validity of discrete choice experiments for measurement of consumer preferences for origin and extrinsic quality cues.Food Quality and Preference,34, 50–61.

Loureiro M L, Umberger W J. 2003. Estimating consumer willingness to pay for country-of-origin labeling.Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics,28, 287–301.

Magidson J, Vermunt J. 2002. Latent class models for clustering: A comparison with K-means.Canadian Journal of Marketing Research,20, 36–43.

Migliore G, Galati A, Romeo P, Crescimanno M, Schifani G.2015. Quality attributes of cactus pear fruit and their role in consumer choice: The case of Italian consumers.British Food Journal,117, 1637–1651.

Miller-Graff L E, Howell K H, Martinez-Torteya C, Hunter E C. 2015. Typologies of childhood exposure to violence:Associations with college student mental health.Journal of American College Health,63, 539–549.

Moor U, Ldma P P, Moor A, Heinmaa L. 2014. Consumer preferences of apples in Estonia and changes in attitudes over five years.Agricultural & Food Science,23, 135–145.

NBSC (National Bureau of Statistics of China). 2015. Statistics.[2016-08-26]. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2015/indexch.htm (in Chinese)

Nie J, Cong P, Yang Z. 2005. The report of Chinese apple pesticide residue.Chinese Agricultural Science Bulletin,21, 88–90. (in Chinese)

Ortega D L, Wang H H, Wu L, Olynk N J. 2011. Modeling heterogeneity in consumer preferences for select food safety attributes in China.Food Policy,36, 318–324.

Peterson H H, Bernard J C, Fox J A S, Peterson J M. 2013.Japanese consumers’ valuation of rice and pork from domestic, US, and other origins.Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics,38, 93–106.

Roberts J A. 1996. Green consumers in the 1990s: Profile and implications for advertising.Journal of Business Research,36, 217–231.

Robinson R, Smith C. 2002. Psychosocial and demographic variables associated with consumer intention to purchase sustainably produced foods as defined by the Midwest Food Alliance.Journal of Nutrition Education & Behavior,34, 316–325.

Schooler R D. 1965. Product bias in the Central American common market.Journal of Marketing Research,2,394–397.

Umberger W J. 2004. Will consumers pay a premium for country-of-origin labeled meat.Choices,19, 15–19.

USDA (United States Department of Agriculture). 2009. Cool regulations. [2016-08-26]. https://www.ams.usda.gov/rulesregulations/cool

USDA (United States Department of Agriculture). 2014. The EU’s country of origin labeling (COOL) policy. [2017-03-01]. http://gain.fas.usda.gov/Recent%20GAIN%20 Publications/The%20EU’s%20Country%20of%20 Origin%20Labeling%20(COOL)%20Policy_Brussels%20 USEU_EU-28_3-19-2014.pdf

Verlegh P W, Steenkamp J E. 1999. A review and metaanalysis of country-of-origin research.Journal of Economic Psychology,20, 521–546.

Wang C K, Lamb C W. 1983. The impact of selected environmental forces upon consumers’ willingness to buy foreign products.Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science,11, 71–84.

Xie J, Gao Z, Swisher M, Zhao X. 2015. Consumers’preferences for fresh broccolis: Interactive effects between country of origin and organic labels.Agricultural Economics,47, 181–191.

Yiridoe E K, Bonti-Ankomah S, Martin R C. 2005. Comparison of consumer perceptions and preference toward organic versus conventionally produced foods: A review and update of the literature.Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems,20, 193–205.

Yu X, Gao Z, Shimokawa S. 2016. Consumer preferences for US beef products: a meta-analysis.Journal of Agricultural Economics/Rivista di Economia Agraria,71, 177–195.

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2018年6期

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2018年6期

- Journal of Integrative Agriculture的其它文章

- Factors influencing hybrid maize farmers’ risk attitudes and their perceptions in Punjab Province, Pakistan

- Long-term grazing exclusion influences arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and their association with vegetation in typical steppe of lnner Mongolia, China

- Soil microbial characteristics and yield response to partial substitution of chemical fertilizer with organic amendments in greenhouse vegetable production

- Reducing nitrogen fertilization of intensive kiwifruit orchards decreases nitrate accumulation in soil without compromising crop production

- Ultrastructure of the sensilla on antennae and mouthparts of larval and adult Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae)

- In field control of Botrytis cinerea by synergistic action of a fungicide and organic sanitizer