Counseling strategies for nutritional anemia by family physicians in Saudi Arabia, 2016: Implication for training

Fakhralddin Abbas Mohammed Elfakki, Njood Suliman Muhammed AlBarrak

1. Assistant Professor of Community Medicine, Family and Community Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine Tabuk University, Tabuk, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

2. Health Consultant at Vision Health Consultancy, Khartoum,Sudan

3. Faculty of medicine, Qassim University, Qassim, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Counseling strategies for nutritional anemia by family physicians in Saudi Arabia, 2016: Implication for training

Fakhralddin Abbas Mohammed Elfakki1,2, Njood Suliman Muhammed AlBarrak3

1. Assistant Professor of Community Medicine, Family and Community Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine Tabuk University, Tabuk, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

2. Health Consultant at Vision Health Consultancy, Khartoum,Sudan

3. Faculty of medicine, Qassim University, Qassim, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Context:Prevalence of nutritional anemia among Saudi female and children is evident and has been reflected in different studies, most of researchers conclude that there is a gap in dietary counseling in addition to the poor awareness of community about appropriate dietary habits; this study is trying to assess counseling behavior and training competency of family physician at primary health centers with respect to nutritional anemia.Objective:Study objective is to assess general beliefs, practice, and level of training in counseling by family physician.Methodology:This is a cross-sectional study design; data collected using self-administered questionnaire provided to the doctor at clinic site.Results:The most commonly learned counseling technique in order as follows motivational interviewing (68%), cognitive behavioral therapy (58%), and 15-Minute Hour approach (53%).Conclusion:This study confirms the presence of positive counseling beliefs and practices by family physicians; however, the result is also reflects the current reluctant state of family physicians in devoting ample time for nutritional anemia counseling.

Counseling; beliefs; dietary habits; nutritional anemia

Introduction

Family physicians at primary health centers are considered as gatekeepers and frontline physicians who handle patients at the first encounter; therefore, more attention is needed so as not to miss patients with nutritional anemia as a result of inappropriate dietary habits that could be well managed through provision of comprehensive counseling at the first encounter. The prevalence of nutritional anemia among Saudi women and children is evident and has been reflected in several studies [1, 2]; most researchers conclude that there is a gap in dietary counseling in addition to poor awareness of the community about appropriate dietary habits in the Qassim region, which is located in the heart of the country and has a total population of 1,402,974 and a geographical area of about 58,046 km2[3, 4]. Qassim has 18 government hospitals providing secondary health care in addition to 172 primary health care facilities; the frequency of patient visits to primary health care facilities is 100—105 patients per health center per day, of which 45 are men and 60 are women or children [5].This study aims to assess counseling beliefs of family physicians at primary health centers with respect to nutritional anemia.

Family physicians’ beliefs, practices, and previous training in dietary counseling need more exploration with a focus on counseling for nutritional anemia as a result of inappropriate dietary habits.

This study hypothesizes that family physicians at primary health centers have poor counseling practices and negative beliefs toward counseling patients with nutritional anemia as a result of inappropriate dietary habits; likewise, they do not receive comprehensive training in patient counseling.

General objective

We aimed to assess beliefs toward counseling for nutritional anemia and dietary habits by family physicians working at primary health care centers in the Qassim region in Saudi Arabia.

Specific objective

We aimed to determine common types of counseling approaches studied by family physicians during the family medicine training program. Further, we aimed to provide recommendations for family physicians’ beliefs, practices, and training in counseling approaches for nutritional anemia as a result of inappropriate dietary habits at the primary health care level.

Research questions

The aim of the study is to answer the following questions:

?Why do patients with nutritional anemia as a result of inappropriate dietary habits not receive enough counseling by family physicians at primary health care clinics?

?Do family physicians at primary health centers receive a comprehensive package of training on patient counseling?

Methods

Research questions and measured variables were used to help explain the previously stated null hypothesis claiming that family physicians have negative beliefs toward counseling.

Participants

The participants were family physicians working at family health centers; they included a selection of those who were recruited and appointed by the Saudi ministry of health in Riyadh to work in the Qassim region. The sample population consists of family physicians working at primary health care facilities in the Qassim region.

Study design

This is a cross-sectional, facility-based study exploring counseling for nutritional anemia beliefs, practices, and training with regard to family physicians at primary health care facilities in the Qassim region.

Study area

The study area is the primary health care facility where staff(i.e., physician, nurse, and technician) are available and ready to counsel patients with nutritional anemia and inappropriate dietary habits; therefore, patients are expected to come for clinical and/or counseling services at the first encounter as a prerequisite before being transferred to a secondary health facility.

Data collection tools

Data were collected by a self-administered questionnaire adapted from a questionnaire used in a study of family physician beliefs and practices on mental health counseling [6].

Sampling and technique

The study involves family physicians working at the level of health centers in the Qassim region represented by the sample taken from the capital city of the region, Buraydah, which contains approximately 49% of the region’s total population [5].

Inclusion and e xclusion c riteria:For inclusion, family physicians had to be working at government health centers.Family physicians working at private sector health facilities and physicians working at accident and emergency care centers were excluded.

Sampling technique:The unit of analysis is the resident family medicine physician or the corresponding staff at the primary health facility that provides patient counseling; sampling followed the rule of dual frame sampling for a stand-alone facility survey approach [7]; therefore, sampling of health centers followed the procedure of simple random sampling technique as a perfect, accurate, and updated list of health facilities was used to create a list frame sample for facilities and an area frame sample to balance the coverage through the allocation of health facilities with use of an updated map from the Ministry of Health.

On the other hand, geographical balance was considered when health centers were selected; therefore, health centers were identified by our dividing the sample (67) by five areas,resulting in 12 health centers being selected from five directions; that is, i.e. the north, south, east, west, and central parts of the city.

Both the northern area and the city center are more populated than the three other directions; hence, these two areas had additional selection of two or three health facilities to give 14 or 15 health centers in total.

Simple random sampling was also applied for sampling of the family physicians in health centers.

Sample size

The sample size was determined on the basis of updated information from the Ministry of Health regarding the number of current primary health facilities and the estimated workforce at the level of primary health facilities in the Qassim region:125 family physicians working in 125 health centers and representing the total sampled population.

Therefore, the sampled facilities were used as a frame from which staff were sampled by ratio-based techniques (6); therefore, of the total number of family physicians in the region(125) resident family physician), the study covered more than 50% (67) of the total number (125) of family physicians in the region, with an equal chance of each staff being selected in the sample.

Statistical methods for data analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics version 21 was used to analyze the six Likert scale questions on family physicians’ beliefs and practices in respect of the general concept of counseling and nutritional anemia counseling, in addition to five dichotomous questions yielding a yes/no response that elicit answers about previous training in five counseling approaches.Frequency tables with percentages for six Likert scale variables were generated, and further statistical tests, such as bivariate correlations, were performed at the 0.5 significance level.

Results

Response rates

Sixty-seven self-administered questionnaires were distributed to resident family physicians working at primary health centers; there was a 100% response rate. The respondents are male and female family physicians who were appointed by the Saudi Ministry of Health to work in the primary health care sector.

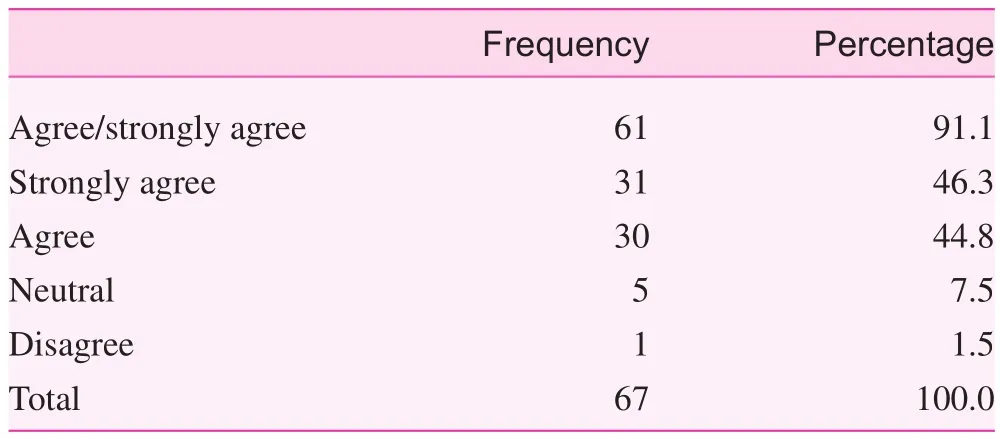

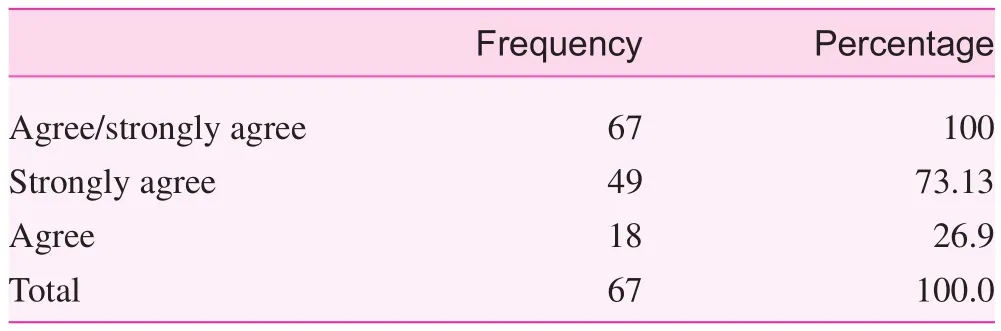

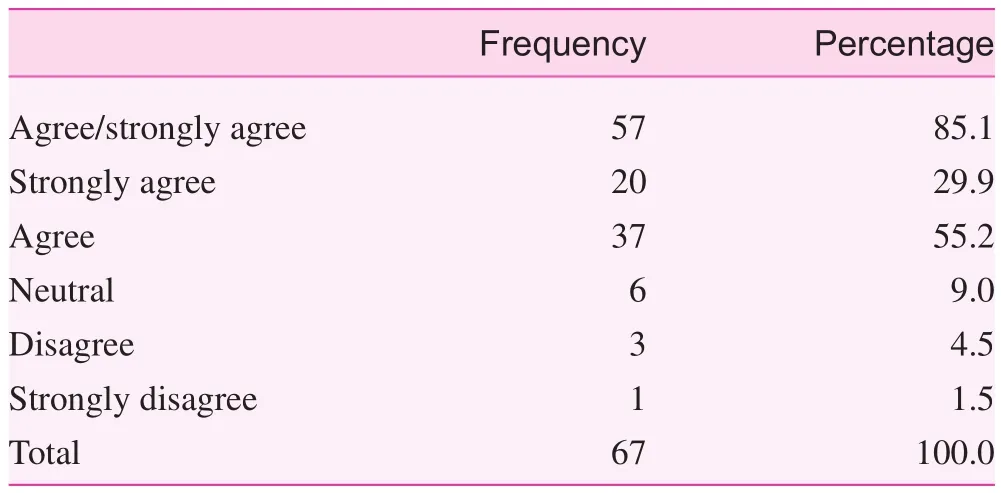

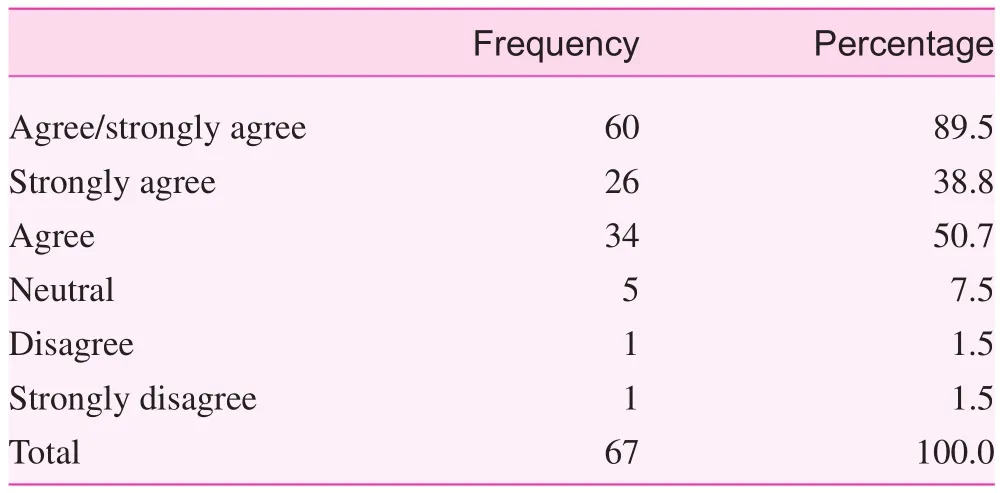

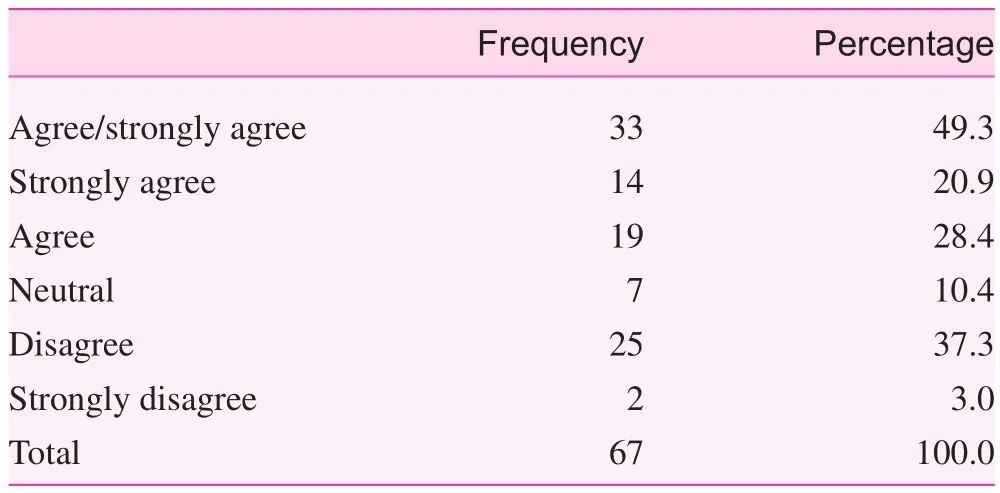

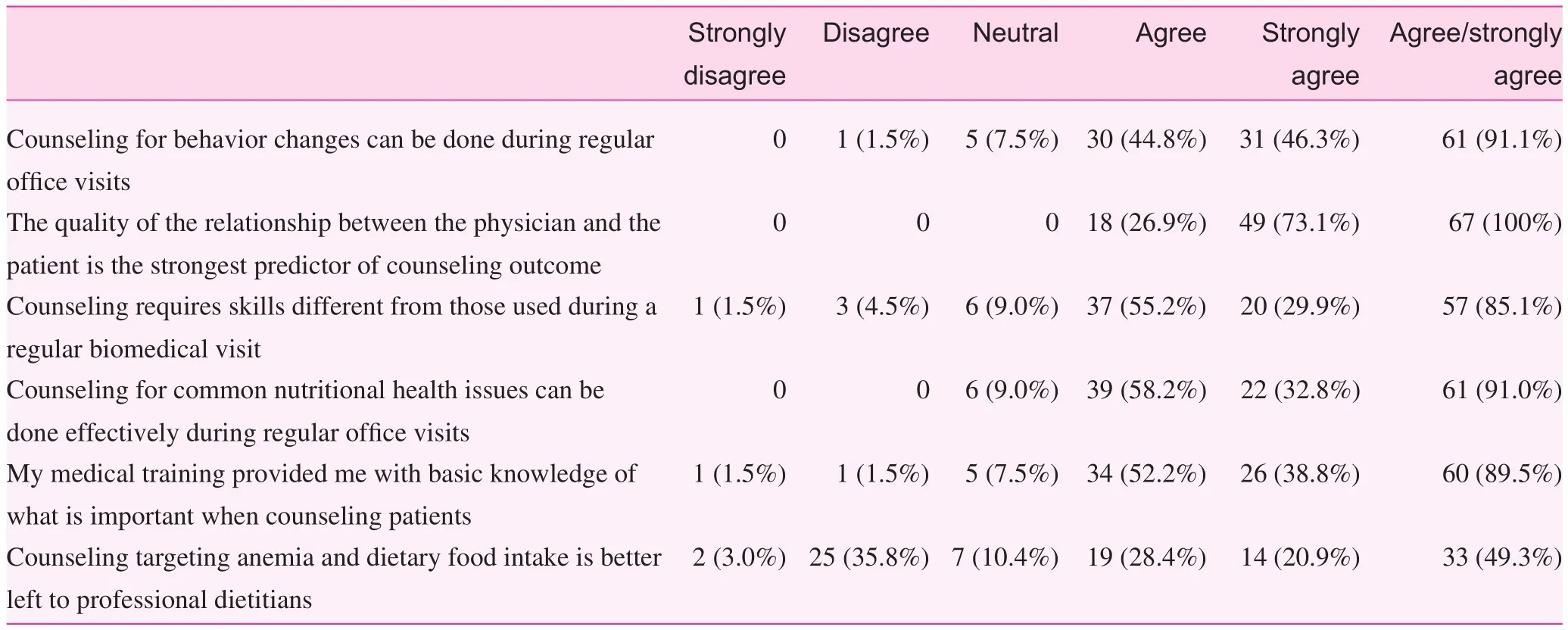

Beliefs about the role of counseling in practice

Most of the respondents either agreed or strongly agreed that counseling for nutritional anemia as a result of inappropriate dietary habits can be done during regular office visit (91%)(Table 1). Most of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the quality of the relationship between the physician and the patient is the strongest predictor of counseling outcome(100%) (Table 2). A large proportion of respondents (85%)agreed or strongly agreed that counseling requires different skills, which could be gained through knowledge and training practice targeting physicians on when, why, and how to approach a patient with nutritional anemia, which is different from superficial counseling at regular consultation during a regular clinical visit (Table 3). Eighty-nine percent of respondents either agreed or strongly agreed that they had received basic knowledge during previous training on what is important when counseling patients (Table 4). Slightly less than half of the respondents (49.3%) agreed or strongly agreed that counseling targeting nutritional anemia as a resultof inappropriate dietary habits is better left to professional dietitians (Table 5).

Table 1. Regular office visit counseling is possible

Table 2. The quality of the physician—patient relationship predicts counseling outcome

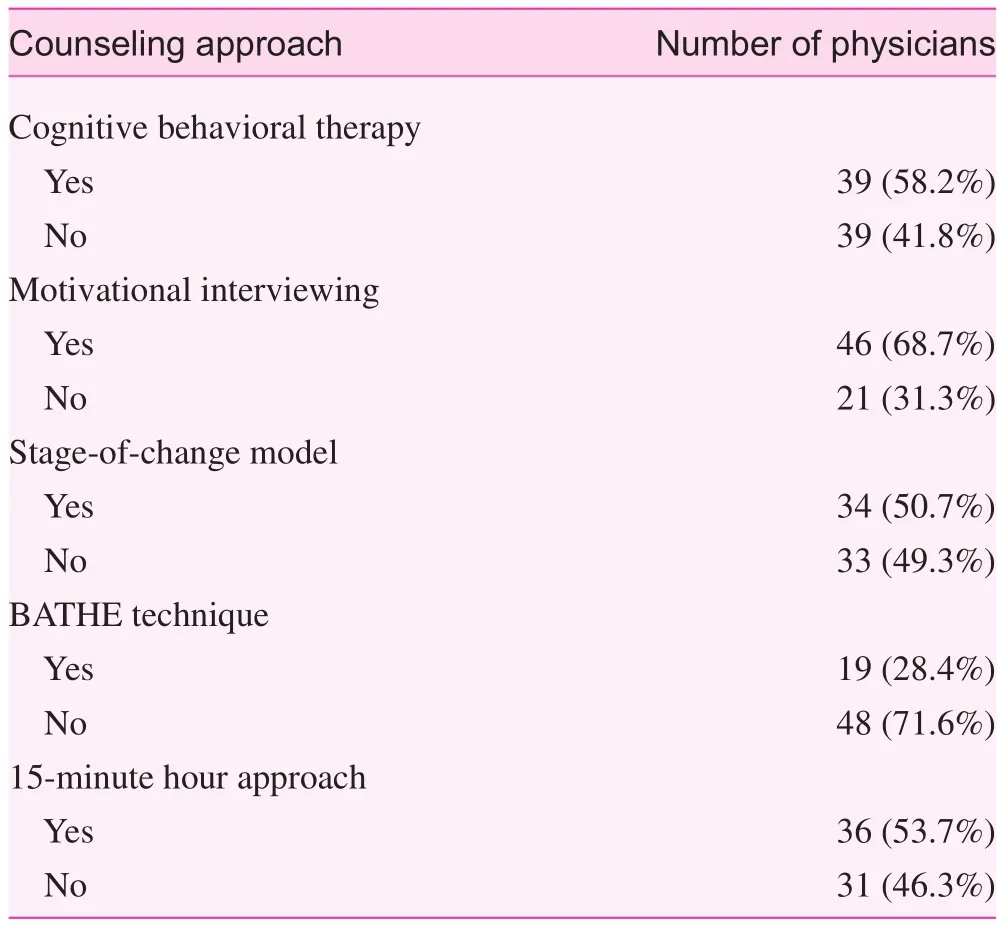

Counseling approaches learned during previous training

Motivational interviewing was the most commonly used and most commonly learned counseling technique during a previous family medicine residency program (68%), followed by cognitive behavioral therapy (58%), and then the 15-minute hour approach (53%); however, the stage-of-change model(i.e., description of the hierarchical stages that we should follow to change our daily habits), and background, affect, trouble, handling, and empathy (BATHE) techniques were the least common approaches learned during previous training(50% and 28% respectively) as shown in Table 6.

Table 3. To provide dietary counseling, competent counseling skills other than the general ones are required

Table 4. I received enough training on counseling

Discussion

This study elicited family physicians’ beliefs and practices regarding patient counseling at primary health care facilities. Likewise, it reflects the general knowledge and perception of family physicians regarding the essential counseling concepts and the beneficial effect with regard to counseling for nutritional anemia as a result of inappropriate dietary habits as an important tool for providing preventive services at family health care centers in Saudi Arabia; researchers in the field have confirmed the valuable impact and acceptability of family physician counseling [8].

The study highlights some valuable facts about the focus of the previous family medicine training of the participants with regard to the types of commonly used counseling approaches that have been learned (Table 6).

Table 5. Nutritional anemia counseling is a dietician’s job

Table 6. Counseling approaches learned during previous training

Generally speaking, a large proportion of the sample believed that their counseling efforts have generally been effective in helping patients make positive changes; similarly, most of the respondents either agreed or strongly agreed that they had received basic knowledge of what is important when counseling patients during previous training. In addition, a modest majority believed that counseling for nutritional anemia as a result of inappropriate dietary habits involves actively teaching the patient good selection of an iron-containing diet.

On the other hand, most of the research sample either agreed or strongly agreed that counseling for anemia as a result of inappropriate dietary habits can be done during a regular office visit (Table 1). However, it is valuable to report that about half of the respondents (33; 49.3%) agreed or strongly agreed that counseling targeting anemia and dietary habits is better left to professional dietitians (Table 7).

This wide agreement of beliefs on nutritional anemia counseling as a responsibility of other professionals, however, highlights family physicians’ conception of the counseling process as an additional task that should be delegated to dietitians or other health professionals (Table 5). Further, this finding could also be interpreted in light of other studies as time constraint or failure of family physicians to plan their time so as to perform preventive roles during regular patient visits [9, 10].

The response by family physicians suggesting their belief and preference is to delegate dietary counseling of nutritional anemia to dietitians or other health professionals points to the current reluctant state of family physicians in devoting ample time for provision of this valuable preventive service. This finding is consistent with the findings of other study findings on time constraints and multiple causes as a barrier to counseling activities at primary health care facilities [11, 12].

Table 7. Beliefs about counseling among family physicians (n=67)

With regard to the question about counseling approaches that have been used and learned during training, motivational interview was the most commonly used counseling approach,followed by cognitive behavioral therapy and the 15-minute hour approach; however, the stage-of-change model with five stages (precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action,maintenance, and relapse) [13] and BATHE techniques were the least used ones.

This response explains why the preference for using the motivational interview approach over cognitive behavioral therapy and the 15-minute hour approaches is to some extent influenced by the nature and simplicity of performing the technique itself. In contrast, poor training or no training received on BATHE techniques, most likely, is a simple expression of the low response when asked about this approach. This finding is coherent with the findings of previous studies on medical school curricula and nutrition education [14]. This study finding adds new information on the positive beliefs and practices of family physicians with regard to dietary counseling in the primary health care setting; however, this trend in belief is for counseling in general.

Limitations

One of limitations of this study is the underreporting of family physicians’ qualifications, as little is known about the recruitment procedures and the required type of training for family physicians before appointment. Another limitation is the small sample size of the study population drawn from one geographical area by a ratio-based technique to represent another four cities with the same or a slightly smaller population.

Conclusion

This study confirms the presence of positive counseling beliefs and practices of family physicians; however, the results also reflect the current reluctance of family physicians to devote ample time for counseling for nutritional anemia as a result of inappropriate dietary habits.

Recommendations

?Scaling up of programs for continuous professional development involving family physicians in the primary health care setting is recommended.

?Delivery of updated guidelines on counseling in the primary health care setting with accompanying training workshops covering the main concepts is recommended.

?Specific counseling on nutritional anemia as a result of inappropriate dietary habits should be done through incorporation of continuous medical education training of family medicine practitioners at primary health centers.

?Introduction of core modules on dietary counseling to the residency program of family medicine is crucial.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

1. Al-Assaf AH. Anemia and iron intake of adult Saudis in Riyadh City-Saudi Arabia. Pak J Nutr 2007;6(4):355—8.

2. Waggiallah HA, Alzohairy M. Awareness of anemia causes among Saudi population in Qassim Region, Saudi Arabia. Natl J Integr Res Med 2013;4(6):35—40.

3. Riya AlQuaiz AM, Gad Mohamed A, Khoja TA, AlSharif A,Shaikh SA, Al Mane H, et al. Prevalence of anemia and associated factors in child bearing age women in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.J Nutr Metab 2013;2013:636585.

4. Kedir H, Berhane Y, Worku A. Khat chewing and restrictive dietary behaviors are associated with anemia among pregnant women in high prevalence rural communities in eastern Ethiopia.PLoS One 2013;8(11):e78601.

5. Directorate General of Information and Statistics. Health statistical year book. Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Ministry of Health; 2009.

6. Fraser K, Oyama O, Burg MA, Spruill T, Allespach H. Counseling by family physicians: implications for training. Fam Med 2014;47(7):517—23.

7. World Health Organization. Health facility survey: tool to evaluate the quality of care delivered to sick children attending outpatient facilities. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003.

8. McKee MD, Maher S, Deen D, Blank AE. Counseling to prevent obesity among preschool children: acceptability of a pilot urban primary care intervention. Ann Fam Med 2010;8(3):249—55.

9. Kolasa KM, Rickett K. Barriers to providing nutrition counseling cited by physicians: a survey of primary care practitioners. Nutr Clin Pract 2010;25(5):502—9.

10. Yarnall KS, Pollak KI, ?stbye T, Krause KM, Michener JL.Primary care: is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health 2003;93(4):635—41.

11. Frank E, Segura C, Shen H, Oberg E. Predictors of Canadian physicians’ prevention counseling practices. Can J Public Health 2010;101:390—5.

12. Howe M, Leidel A, Krishnan SM, Weber A, Rubenfire M,Jackson EA. Patient-related diet and exercise counseling:do providers’ own lifestyle habits matter? Prev Cardiol 2010;13(4):180—5.

13. Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot 1997;12(1):38—48.

14. Adams KM, Kohlmeier M, Powell M, Zeisel SH. Nutrition in medicine nutrition education for medical students and residents.Nutr Clin Pract 2010;25(5):471—80.

Njood Suliman Muhammed AlBarrak

Internship student, Faculty of medicine, Qassim University,Qassim, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

E-mail: njoodsb@hotmail.com

25 October 2016;Accepted 17 March 2017

Family Medicine and Community Health2017年4期

Family Medicine and Community Health2017年4期

- Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- An automated management system for the community health service in China

- Survey and analysis of patient safety culture in a county hospital

- Additive manufacturing techniques and their biomedical applications

- A case of probable sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

- Seguin Form Board as an intelligence tool for young children in an Indian urban slum

- Assessment of family physicians’ knowledge of childhood autism