HARD CELL

BY HATTY LIU

HARD CELL

BY HATTY LIU

Telecom operator Seatel discusses the challenges and strategies facing Chinese companies abroad

將4G網(wǎng)絡(luò)鋪去東南亞

When Thailand’s government backed out of an agreement to lay 870 kilometers of high-speed Chinese railway through the country last spring due to financing disputes, skeptics were quick to suggest cracks were appearing in China’s “One Belt One Road” (OBOR) initiative.

Indeed, for a project on the scale and ambition of a modern-day Silk Road, which aims to build infrastructure connecting around 50 countries (and counting) over land and sea, most people were surprised that roadblocks hadn’t appeared sooner.

Over the past year, as another high-speed rail project failed to materialize in Indonesia and plans to build a vast industrial park sparked protests in Sri Lanka, critics having been impatiently trying to figure out the endgoal of China’s overseas infrastructural investments—will OBOR ultimately deliver anything new, or will China just ferry all the same goods to more countries somewhat faster than before?

To one Chinese-owned private telecommunication provider, the Southeast Asia Telecom Group (Seatel), the answer is quite clear: build it, but make sure you have to have something to deliver too.

“Some of the Chinese projects [under OBOR] are about building other infrastructure, such as office buildings for the local government; some…are providing equipment. Very few, practically no companies invest in or operate telecom projects,”says Zhang Yudong, Seatel’s Chief Administrative Officer. “For this product, because the end-users are the general public, we can have an idea of the feelings about the products and services from a Chinese company and the advanced technologies.”

After all, the ancient Silk Roads from which OBOR took inspiration were not so much defined, physical routes than a loose network of trading links, sustained by the appetite for fine Chinese silk and other goods. It was the silk that created the road—not the other way around.

“So far, most of the products provided, delivered, or conducted by Chinese companies [in the region] are providing basic infrastructures to the developing countries, like building bridges or building reservoirs or building roads,” Zhang says. He believes Seatel is at the forefront of something different: “Our company is in the business of providing hightech telecom communication, so if our products are excellent and outstanding, then the local people have a better impression of Chinese companies.”

Specifically, Seatel is in the business of providing what aims to be the“most advanced 100 percent 4G VoLTE [voice over LTE] mobile communication network in [the] Southeast Asia area,” according to the company’s official statements. As mobile operators usually use 4G (LTE) systems for carrying data only, reverting to 2G or 3G systems for carrying voice, Seatel’s plans would make it the first 100 percent 4G carrier in the region.

Sales representatives present Seatel's proprietary terminals at an event in December, 2016

THE ANCIENT SILK ROADS FROM WHICH OBOR TOOK INSPIRATION WERE A LOOSE NETWORK OF TRADING LINKS, SUSTAINED BY THE APPETITE FOR FINE CHINESE SILK

On the most basic level, the project concerns infrastructure: installing 10,000 kilometers of fiber routes under the ground of the company’s host country Cambodia, a total investment of 400 million USD. However, the company also offers user-oriented mobile and wireless communication services, making a bold bid to differentiate itself from Cambodia’s existing telecom operators—as well as the general blueprint of mobile network development worldwide—by jumping straight into a 4G-only service package.

This strategy, says Zhang, takes to the logical extreme what developmental theorists have long called the “l(fā)eapfrog” model of telecom development in the Third World: “The system in Cambodia is relatively primitive; not many people use landlines; but then because we introduce mobile telecom technologies, they can ‘leap’ into smartphones…and you can use the internet and call at the same time.”

Seatel’s deputy sales manager Cheang Kimeang, a longtime resident of Phnom Penh, presents these developments as beneficial for local economic growth—“it brings connectivity not only to the entire country but to the entire world…starting from local people, [to] local investors, [to] foreign investors.”Local social-media marketing analyst Anthony Galliano, on the other hand, puts it in more practical terms:“The market is starving for faster internet...if Seatel can differentiate with demonstrably better speed, the consumer will shift,” he told the Phnom Penh Post back when Seatel launched their services in 2015.

It’s also a strategy that will likely give Seatel customers faster and better-quality mobile services than is available in most of China itself, where many customers still straggle with 2G and 3G infrastructure as they wait for state operators’ 4G upgrades. There’s also opportunity for China’s rising smartphone makers to showcase their products in Southeast Asian markets through telecom investments: in addition to their own proprietary smartphone models, Seatel customers have access to the latest flagship phones from Huawei and ZTE.

Registered in Singapore under Chinese ownership in 2014, Seatel has established subsidiaries in Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Nepal, Bangladesh, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Guangzhou, China. The company entered Cambodia the same year it was founded by buying out Russianrun mobile company GT-TELL, which at the time had the smallest market share of Cambodia’s seven existing mobile operators. The acquisition helped to internationalize Seatel’s body of employees, which is now composed of Chinese technical staff integrated into a team which is 80 percent Khmer and includes employees from India, France, South Korea, and Central Asian nations, some of which are regions where Seatel hopes to expand.

Zhang is betting on his team’s diversity to ensure future success, as “having technical skills and international connections, including foreign languages, is important in a Chinese company to communicate with its employees and customers.”

Is this a blueprint for success for OBOR initiatives in risky and emerging markets? For now, it’s too soon to tell. But with Seatel having established a foothold in all 25 provinces of Cambodia within two years of launch, with an eye to becoming at least the country’s second largest telecom company in two years, it makes a persuasive argument.

Chinese Characters: Cognition

(Chinese-German Edition)

Winner of the Friedhelm Denninghaus Prize 2015

·Available in both German and English

·15 lessons with 295 characters

·Exercises and games designed to develop students’ ability to recognize and use characters

·From the “Chinese Language, Chinese Characters”textbook series, planned by Dr. Brigitte K?lla of Zurich University, expert in teaching Chinese

·Entry-level textbook for use after Chinese Characters: Writing and Chinese Language: I

·Complete with instruction manual

The Friedhelm Denninghaus Prize is awarded every two to three years for outstanding achievements in the promotion of Chinese education in Germanspeaking countries by the German Association of Chinese teachers (FaCh).

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Wan Yexin is a professor and PhD advisor at Beijing Language and Culture University and an expert in etymology and calligraphy.

WHERE TO BUY

Both the German and English editions of the entire series are available at www.theworldofchinese.com/store/

THE YOUNG MAN TOOK A FOLDING DAGGER OUT FROM HIS POCKET, AND TAPPED IT ON THE TABLE

[CONTINUED FROM PAGE 23]

happy families milling about like ants; their happiness seemed to spread like fire, around the old men with long beards waiting under the wall to read people’s fortunes.

Zhao threw another cigarette butt to the ground. He’d already seen the plaza go from deserted to packed, and thought over all the relatively major events in his life in detail, especially those who had died—relatives, friends, his wife, his daughter, people from the factory. He thought about their expressions at various moments, smiling, contrite, disappointed, sad, lonesome, pained. This was how life went—he wasn’t extremely old but he wasn’t young, didn’t have a shot at prospering, what did he hope for in life? What did he hope for his child? He thought about Huajun again—where was that little fucker?

Zhao still hadn’t eaten, but he wasn’t hungry. He felt like his stomach was full of cigarette smoke, pushing against the walls of his stomach like air in a balloon. By the time the streetlights lit up, Zhao felt that it was time for him to get a move on, go get something to eat. He felt apprehensive for a second—he’d spent the entire day at the plaza, observing the purity of the children and happiness of the families.

Zhao went to the Pig Head Diner to drink a bit, and eat a bit of pig’s cheek and trotter. This restaurant was opened by people from out of town—supposedly from Heilongjiang—who’d given their restaurant a rather unusual name: Pig Head Diner. This name was quickly engraved into the minds of the people of Tongcheng: walking past the plaza towards the train station, one could quickly discover this restaurant, looking like a guesthouse from a movie of antiquity, its interior populated with dark wooden tables and large vats of liquor in the corners. Zhao knew the restaurant was quite popular, and on holidays would be packed with diners enticed by the smell of pig’s head from across the street. People came to drink, eat, and chat about their hardships over the continual din inside.

The restaurant wasn’t expensive, and it had character—very much an everyman’s restaurant. Before he was laid off, Zhao would frequently come here with his colleagues to drink after work.

The Pig Head Diner was full of customers. Zhao couldn’t find a table, so when a young man let him, he sat down across from him. Zhao liked this kind of atmosphere: not highclass, just a relaxed environment in which one could sit down, enjoy, and drink. Everyone was unrestrained, speaking in loud voices as to be heard by their companions over the roil of others’. Zhao gnawed on a trotter and enjoyed his drink, satisfied, suddenly feeling quite happy, having already drunk a good deal, just like the young man across from him. He could see something troubling was on the man’s mind, that he was drowning his sorrows in liquor. Zhao didn’t speak, even though he’d been sitting across from him for an hour and a half.

Finally, the young man was drunk. Looking at him, Zhao thought he must know he was drunk. The young man suddenly returned his gaze, eyes shining, filling with tears, and spoke:“I was planning to do them.”

Zhao looked up at the young man, but didn’t say anything.

“Really, I was planning to do them.”The young man took a folding dagger out from his pocket, and tapped it on the table, avoiding Zhao’s gaze, looking at his little weapon, tongue quivering. “I mean, of course I knew; I’m not stupid. I’m poor, what can I do?” Besides castigate himself, what could he do?

“So you’re a university student?”Zhao finally spoke.

“She shouldn’t have lied to me.” The young man spoke, hurt and angry.“I’m not stupid, how could I not know? I made a call, talked to Linlin, everything was easy to figure out. I’m 20-something, I’m educated, am I that easy to fool? I’m not an idiot, I know everything, but what could I do? I’m not brave, I can’t be ‘hard core,’ so I’m not a mover or shaker. I’m too nice, no; too much of a pussy, and I’m broke, so how the fuck can I live with myself? I can’t die, there’s nothing, nothing I can do, I mean, what can I do, really? What can I do?”

Zhao didn’t pay attention to him, and instead looked elsewhere at the middle-aged men, faces beet-red from the alcohol, talking loudly as they smoked and drank. The youth’s voice blurred, became simply a buzz in his ear. Shortly after, he turned to look at the young man, head on the table, silent.

It was already quite late, yet people were still walking in small groups outside the train station, carrying luggage as they scurried about under the pale white light of the streetlights. When Zhao left the Pig Head Diner, the young man was still lying at the table, not making any noise, like a wearied traveler in deep sleep. Zhao knew it was very late, and that he should go home, as he staggered out of the door of the restaurant to see pedestrians in the distance, only dark outlines to him.

A group of youths, cigarettes in their mouths, walked by, full of energy, bouncing about, talking and laughing. Zhao focused to see if Huajun wasamong them, but was met with disappointment; he didn’t know if his son had returned home yet.

Approaching the intersection in front of the stock exchange, he saw a group crowding around something: a traffic accident. Two prominent-looking police cars were parked over there, the vehicle involved surrounded by policemen and a few middle-aged men and women speaking loudly. He couldn’t see much of the accident, only the vehicle’s rear plates—LIAO-T85 something—so he drew nearer. Elbowing his way forward. Zhao was surprised to suddenly see his son, Huajun.

“Zhao Huajun!” Zhao ran forward, and waved his hands as he cried out.

“Dad!” As Huajun stood by the police officers, he turned to face Zhao.

“Where did you go? What were you doing?” Zhao pointed at his son’s nose as he scolded him.

“Zhu Liang was hit by a car.” Huajun pointed to a body, prostrate upon the ground.

“He was hit?” Zhao walked a couple paces closer, and strained to see.

“Dad…” Huajun stuck his hand out and tugged at his shirt.

“Yeah?” Zhao turned his head to look at Huajun.

“I’m hungry.” Huajun spoke, his small Adam’s apple shaking.

— TRANSLATED BY MOY HAU (梅皓)

Author’s Note:“The Pig Head Diner” was completed in 2009 when I first started writing, and I enjoyed writing about the life I was familiar with. Northeast China used to be the PRC’s cradle of industrialization, filled with factories, while factory workers had high social status. In the late 1990s, when massive layoffs hit, these once-glorious factories closed down. Workers all lost their jobs. The entire Dongbei region quickly declined. Those unusual times led to unusual lives and stories, values, and social environment: The desperation of the older generation, the losses and desires of the new generation, the impulsive yet fragile youths, all affected by the industrial decline. In this story, I wrote realistically about the people around me. They are only ordinary, but when putting their ordinary life into words, cruelty manifests.

Are you a writer? Do you have insightful stories to tell about China? The World of Chinese is looking for bright, knowledgeable freelance writers and reporters, with relevant experience and qualifications, to contribute to our bi-monthly print and digital magazine. We cover a wide variety of subjects, from food to film, law to literature, technology to travel, with both regular columns and feature-length articles.

The ideal freelance candidates should be experienced writers who have lived, worked, or traveled in China, and/or the Chinese diaspora, and have a deep understanding of their subject and a lively, engaging style. In return, we offer a competitive word rate and the opportunity to be published in one of best-known English language magazines in China.

To apply, please send a resume and a brief covering letter, stating why you’d like to write for The World of Chinese, along with (ideally) two previously published articles and three story pitches of 50-150 words to rfh@theworldofchinese.com with the subject line “Writers.”

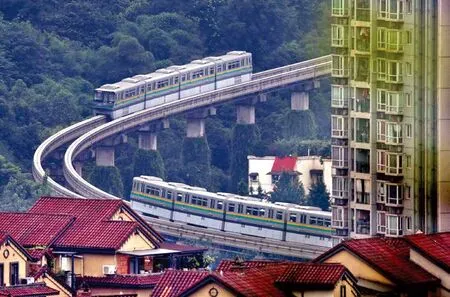

The through train:Line 2 of Chongqing’s mass rail transit network exits a 19-storey building on its route. Residents can access the train via a station in the building.