Uncoupling protein 2 deficiency reduces proliferative capacity of murine pancreatic stellate cells

Sarah Müller, Sandra Maria Klingbeil, Andreea Sandica and Robert Jaster

Rostock, Germany

Uncoupling protein 2 deficiency reduces proliferative capacity of murine pancreatic stellate cells

Sarah Müller, Sandra Maria Klingbeil, Andreea Sandica and Robert Jaster

Rostock, Germany

BACKGROUND: Uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) has been suggested to inhibit mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by decreasing the mitochondrial membrane potential. Experimental acute pancreatitis is associated with increased UCP2 expression, whereas UCP2 deficiency retards regeneration of aged mice from acute pancreatitis. Here, we have addressed biological and molecular functions of UCP2 in pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs), which are involved in pancreatic wound repair and fibrogenesis.

METHODS: PSCs were isolated from 12 months old (aged) UCP2-/-mice and animals of the wild-type (WT) strain C57BL/6. Proliferation and cell death were assessed by employing trypan blue staining and a 5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine incorporation assay. Intracellular fat droplets were visualized by oil red O staining. Levels of mRNA were determined by RT-PCR, while protein expression was analyzed by immunoblotting and immunofluorescence analysis. Intracellular ROS levels were measured with 2’, 7’-dichlorofluorescin diacetate. Expression of senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA β-Gal) was used as a surrogate marker of cellular senescence.

RESULTS: PSCs derived from UCP2-/-mice proliferated at a lower rate than cells from WT mice. In agreement with this observation, the UCP2 inhibitor genipin displayed dosedependent inhibitory effects on WT PSC growth. Interestingly, ROS levels in PSCs did not differ between the two strains, and PSCs derived from UCP2-/-mice did not senesce faster than those from corresponding WT cells. PSCs from UCP2-/-mice and WT animals were also indistinguishable with respect to the activation-dependent loss of intracellular fat droplets, expression of the activation marker α-smooth muscle actin, type I collagen and the autocrine/paracrine mediators interleukin-6 and transforming growth factor-β1.

CONCLUSIONS: A reduced proliferative capacity of PSC from aged UCP2-/-mice may contribute to the retarded regeneration after acute pancreatitis. Apart from their slower growth, PSC of UCP2-/-mice displayed no functional abnormalities. The antifibrotic potential of UCP2 inhibitors deserves further attention.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2016;15:647-654)

pancreatitis;

proliferation;

stellate cell biology;

uncoupling protein 2

Introduction

Regeneration of the exocrine pancreas after pancreatitis is a tightly regulated process that involves transient phases of inflammation, metaplasia, and redifferentiation. The regenerative process is driven by coordinated interactions between resident and nonresident cells with acinar cells, leukocytes and extracellular matrix (ECM)-producing cells as the key players.[1]Pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs) are the main source of ECM proteins in the diseased pancreas.[2,3]Quiescent PSC (roughly 4% of all pancreatic cells[4]) store vitamin A in fat droplets[4,5]and display properties of stem cells.[6]In response to pancreatic injury, the cells undergo a transition from a quiescent to an activated stage,[2,3]which is characterized by an enhanced expression of the myofibroblastic marker α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA).[4,5]PSC activation involves cell proliferation, an enhanced capability to synthesize large amounts of collagen type I and other ECM proteins, as well as exhibition of a secretory phenotype that is characterized by the secretion of various profibrogenic and mitogenic mediators.[2,3]

Potent triggers of ECM synthesis and PSC proliferation include transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), respectively.[7,8]In addition, ethanol metabolites[9]and oxidative stress[10,11]have been directly implicated in the activation process. Enhanced deposition of ECM is considered as an essential step of pancreatic wound healing and not pathological per se. Noteworthy, PSC activation has been shown to contribute to regeneration early after acute necrotizing pancreatitis in humans.[12]In the context of chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer, however, PSC activation persists and results in pancreatic fibrosis, a characteristic feature and a putative progression factor of both diseases.[2,3]An improved understanding of the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms may eventually lead to the development of novel therapies for chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer, which are based on the inhibition of fibrosis. On the other hand, promoting the physiological wound healing function of activated PSC may be an effective approach to support regeneration after acute pancreatitis or episodes of chronic pancreatitis progression.

We have recently shown that mice which are lacking uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2), a carrier protein of the inner mitochondrial membrane,[13-15]are prone to a retarded tissue regeneration after acute pancreatitis: Compared with wild-type (WT) mice, a more severe pancreatic damage at late time points after the induction of cerulein pancreatitis (24 hours and 7 days, respectively) was observed.[16]Our findings are in line with previous investigations, which have shown an increased expression of UCP2 in two independent models of acute pancreatitis, cerulein-induced pancreatitis in mice and taurocholate-induced pancreatitis in rats (at two degrees of severity).[17]Interestingly, in our study a retarded regeneration was detected in aged mice (12 months old) only, and unrelated to acinar cell function.[16]

UCP2 has been suggested as a negative regulator of mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species (ROS) production by decreasing the mitochondrial membrane potential,[18-20]and UCP2 expression in different tissues increases with age.[21]Enhanced UCP2 expression may therefore be important to attenuate ageing-associated oxidative stress burden, as also suggested by studies in UCP2-/-mice.[22,23]

In this study, we addressed the question if functional defects or peculiarities of PSC from UCP2-/-mice may account for the longer persistence of the pancreatic damage in aged mice. Since oxidative stress has also been implicated in PSC activation,[10,11]we hypothesized that putative malfunctions of UCP2-/-PSC might be related to the intracellular ROS level, which was therefore monitored experimentally.

Methods

Animals and reagents

UCP2-/-mice[23]were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Sulzfeld, Germany) and kept on the C57BL/6 background (WT control strain). The mice had access to water and standard laboratory chow ad libitum. For cell isolation, balanced numbers of female and male mice at an age of 12 months were employed. Unless stated otherwise, all reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Deisenhofen, Germany).

Cell culture

PSCs were isolated from mice pancreas by collagenase digestion followed by Nycodenz? (Nycomed, Oslo, Norway) density gradient centrifugation as described before for pancreata from rats.[24]Immediately after isolation, PSCs were resuspended in cryopreservation medium [fetal calf serum (FCS) supplemented with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide] and stored at -150 ℃ until required as previously described.[25]After thawing, the cells were cultured in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium supplemented with 17% FCS, 1% non-essential amino acids (dilution of a 100× stock solution), 105U/L penicillin and 100 mg/L streptomycin (all reagents from Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). After approximately 7 days in primary culture, proliferating PSC reached subconfluency and were harvested by trypsination. Afterwards, the cells were recultured according to the experimental requirements. Unless stated otherwise, experiments were performed with cells passaged no more than one time. Trypan blue staining was used to distinguish live from dead cells and to determine absolute cell counts.

Quantification of DNA synthesis

Cell proliferation was assessed by quantifying incorporation of 5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine (BrdU) into newly synthesized DNA, using the BrdU labelling and detection enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (BrdU ELISA; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Therefore, cells were plated in 96-well plates at equal seeding densities (2×103cells per well) and allowed to adhere overnight. Subsequently, recombinant mouse PDGF, recombinant human TGF-β1 (both from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), genipin, or solvent only (controls) were applied as indicated. After 24 hours, BrdU labelling was initiated by adding labelling solution at a final concentration of 10 μmol/L. Another 24 hours later, labelling was stopped, and BrdU uptake was measured according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Measurement of ROS

For the detection of intracellular ROS levels, 2’, 7’-di-

chlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA) was employed. DCFH-DA, a cell-permeable non-fluorescent probe, is deesterified intracellularly and turns to highly fluorescent 2’, 7’-dichlorofluorescin upon oxidation in the presence of hydroxyl, peroxyl and other ROS activity. Therefore, PSC growing in 96-well plates were preincubated with DCFHDA at a final concentration of 50 mmol/L for 30 minutes, using culture medium without phenol red. Afterwards, the medium was substituted by DCFH-DA-free culture medium (supplemented as indicated), and incubation continued for another 30 minutes. Finally, fluorescence intensity was determined at 495 nm excitation and 529 nm emission wavelengths using an automated fluorescence reader (GloMax-Multi+ Detection System, Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Data are expressed as percentage of controls as described in the figure legend.

Immunoblotting

Protein extracts of PSCs (growing in 24-well plates and pretreated as indicated) were prepared and subjected to immunoblotting analysis as described before,[24]using polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Merck Millipore) for protein transfer. The following primary antibodies were employed: anti-α-SMA (#A2547; Sigma-Aldrich) and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; #sc-20357, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The blots were developed using LI-COR reagents for an Odyssey? Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA) as described before.[26]Signal intensities were quantified by means of the Odyssey? software version 3.0, and normalized to GAPDH prior to the comparison of expression levels.

Cytochemical staining of intracellular fat

Freshly thawed PSC were grown in primary culture on glass coverslips for the indicated periods of time, before they were fixed for 30 minutes in 2.5% paraformaldehyde. Intracellular fat droplets were visualized by oil red O staining as described before.[27]Therefore, three parts of an oil red O stock solution (1% w/v dissolved in isopropanol) were mixed with two parts of distilled water. Afterwards, fixed PSC were incubated with the dye solution for 15 minutes followed by counterstaining with Mayer’s hemalum solution (Merck Millipore).

Detection of senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA β-Gal)

PSCs were cultured on coverslips for 2 days as indicated. Afterwards, SA β-Gal-positive cells were stained using a specific kit according to the instructions of the manufacturer (New England BioLabs, Frankfurt, Germany). The nuclei were counterstained with nuclear fast red (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany). Subsequently, specimens were analyzed by light microscopy, and SA β-Galpositive and -negative cells were counted. All samples were evaluated in a blinded manner.

Indirect immunofluorescence staining

PSC growing on coverslips were fixed with methanol for 10 minutes. Non-specific binding sites were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20; PBS-T) for 30 minutes. Subsequently, antiα-SMA antibody (diluted in PBS-T) was added for 30 minutes. Antibody binding was detected by incubation for 30 minutes with Alexa Fluor 488-labelled goat antimouse IgG (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Darmstadt, Germany). Nuclei were visualized by counterstaining with 4’, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Analysis of fluorescence was performed using a Leica DFC320 fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Quantitative RT-PCR

PSCs growing in 12-well plates were treated with TGF-β1 as indicated, and total RNA was isolated using TriFast reagent (PEQLAB Biotechnologie, Erlangen, Germany). Unless indicated otherwise, all further steps were performed with reagents from Thermo Fisher Scientific. First, any traces of genomic DNA were removed employing the DNA-free kit. Afterwards, 250 ng of RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA by means of TaqMan ?Reverse Transcription Reagents and random priming. Relative quantification of target cDNA levels by real-time PCR was performed in a Viia 7 sequence detection system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Therefore, qPCR MasterMix (Eurogentec, Seraing, Liège, Belgium) and mouse-specific TaqMan? Gene Expression Assays with fluorescently labelled MGB probes were used. The following assays were employed: Mm00446190_m1 (interleukin-6; Il-6), Mm01178820_m1 (TGFβ1), Mm00801666_m1 (α1 type I collagen, Col1a1), and Mm01545399_m1 (hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase; Hprt; housekeeping gene control). PCR conditions were: 95 ℃ for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 15 seconds at 95 ℃/ 1 minute at 60 ℃. The relative amount of target mRNA in untreated WT PSC (control) and all other samples was expressed as 2-(??Ct), where ??Ctsample=?Ctsample-?Ctcontrol.

Statistical analysis

All data were stored and analyzed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0. Values are expressed as mean±standard error (SE) for the indicated number of separate cultures per experimental protocol. Analysis of variance was performed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. For posthoc testing, the Mann-Whitney U test was employed. A

P<0.05 (Bonferroni adjusted) was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

UCP2 deficiency and PSC growth

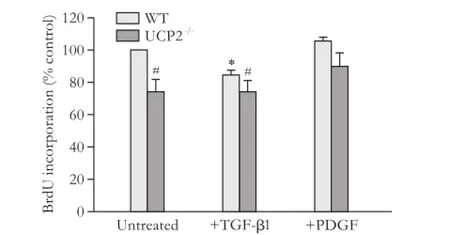

PSC from UCP2-/-mice incorporated less BrdU than PSC from WT mice, suggesting a lower level of DNA synthesis (Fig. 1, columns 1 and 2). The growth advantage of WT cells was also observed by trend when the cells were cultured with TGF-β1, which inhibits PSC growth (columns 3 and 4). Somewhat unexpectedly, PDGF failed to enhance BrdU incorporation of PSC from either strain (columns 5 and 6); a finding that was possibly caused by the fact that the cells were already exposed to FCS. Still, also under these conditions, WT PSC, by trend, incorporated more BrdU than cells of the knockout strain.

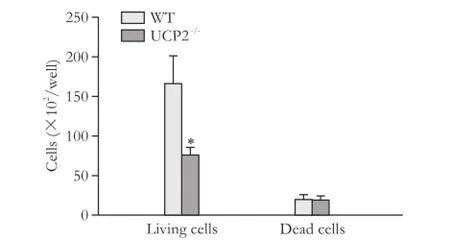

Consistent with the BrdU incorporation data, cell counting showed that WT cells proliferated at a higher rate (Fig. 2, columns 1 and 2). While the numbers of living cells differed significantly, numbers of dead cells were very similar (columns 3 and 4). Nevertheless, the ratio of live and dead cells was lower in cultures of the knockout strain.

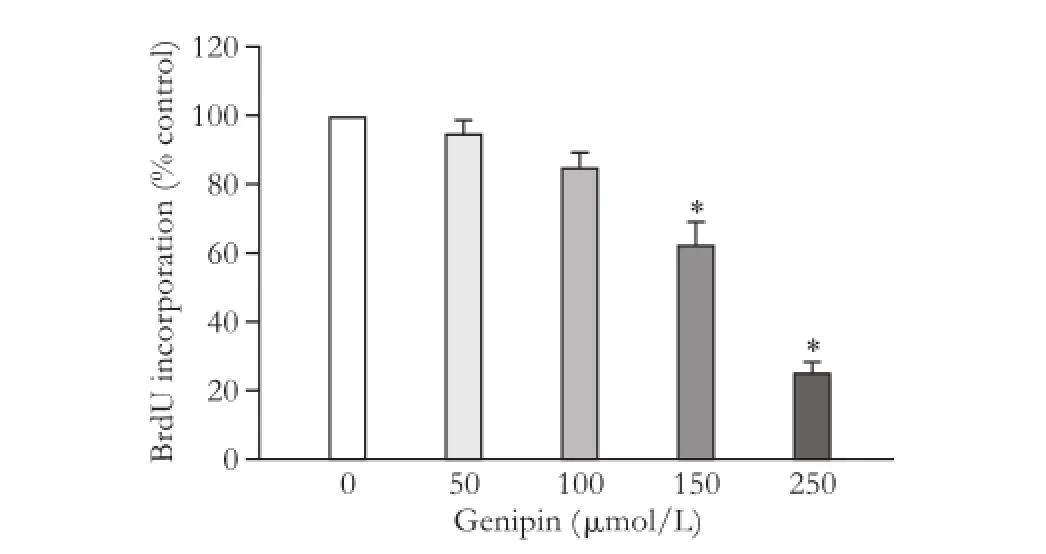

Taking an alternative approach, WT cells were treated with the UCP2 inhibitor genipin.[28]The drug suppressed DNA synthesis in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3) without displaying cytotoxic effects (data not shown), providing further evidence for an important role of UCP2 in PSC proliferation.

ROS levels in PSC from WT and UCP2-/-mice

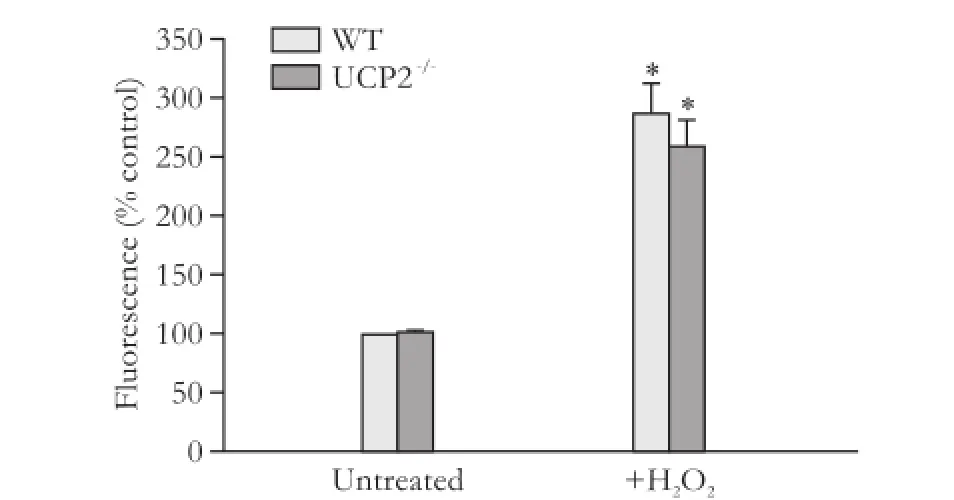

We supposed that the effects of UCP2 on PSC growth might be linked to its putative role in the inhibition of ROS production. A quantification of the intracellular ROS levels, however, revealed no differences between WT and UCP2-/-PSC, independent of the presence or absence of the stressor hydrogen peroxide (Fig. 4).

UCP2-/-deficiency has no effect on PSC activation and senescence

Fig. 1. Basal and cytokine-modulated BrdU incorporation of PSC from WT and UCP2-/-mice. PSC were treated with TGF-β1 (5 ng/mL) and PDGF (10 ng/mL) as indicated for 24 hours before they were labelled with BrdU for another 24 hours. Data are presented as mean±SE (n=9 in each group). *: P<0.01, versus untreated cultures of the same mouse strain; #: P<0.01, versus untreated WT PSC.

Fig. 2. Growth rates of PSC from WT and UCP2-/-mice. PSC were seeded at equal densities and grown for 48 hours before live and dead cells were detected by trypan blue staining. Data are presented as mean±SE (n≥21). *: P<0.01, versus living and dead WT PSC, respectively.

Fig. 3. Effects of genipin on PSC growth. BrdU incorporation of genipin-treated WT PSC was analyzed using the protocol described in the legend to Fig. 1. Data are presented as mean±SE (n=6). *: P<0.05, versus untreated PSC.

Fig. 4. ROS levels in PSC isolated from WT and UCP2-/-mice. DCFH-DA-labeled PSC were treated with hydrogen peroxide (100 μmol/L) for 30 minutes. Data are presented as mean±SE (n=6 in each group). *: P<0.05, versus untreated PSC of the same mouse strain. There were no statistically significant differences between the two strains.

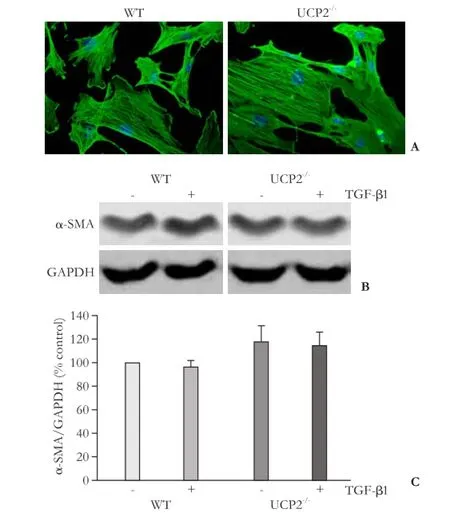

As expected, recultured PSC from WT mice (passage 1) exhibited an activated phenotype that was characterized by the expression of the myofibroblastic protein α-SMA (Fig. 5A, B), which was organized in intracellular

networks of stress fibers. PSC from UCP2-/-mice were virtually indistinguishable from WT cells with respect to organization of the α-SMA fibers and expression of the protein. TGF-β1, which has previously been shown to accelerate PSC activation,[7,8]had no effect on the α-SMA protein levels under the experimental conditions used in this study (Fig. 5C).

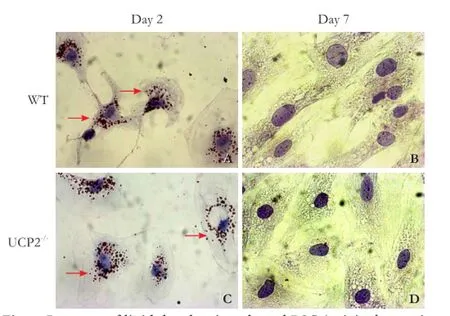

To further monitor the process of PSC activation, cells on days 2 and 7 of primary culture were stained with oil red O to detect intracellular lipid droplets (Fig. 6). In agreement with previous studies,[4,5,27]culture-induced activation of WT PSC was accompanied by a gradual loss of lipid droplets from days 2 to 7 (Fig. 6A, B). Essentially the same changes were observed in UCP2-/-PSC (Fig. 6C, D).

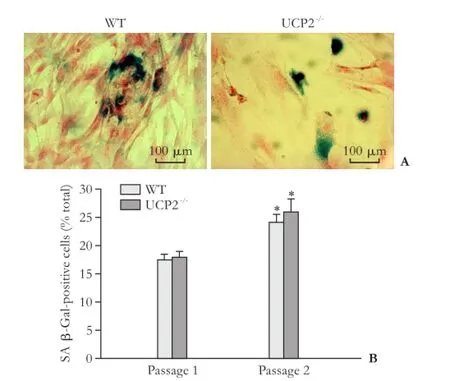

We have previously shown that continuous culture of rat PSC (over several passages) is associated with an increase of senescent cells, which is accompanied by decreased cell proliferation.[29]As shown in Fig. 7, cultures of mouse PSC already after one passage contained significant portions of senescent cells. These portions further increased (in UCP2-/-PSC, by trend only) when the cells were recultured a second time. The high number of senescent PSC most likely resulted from the relatively low seeding density of the cells, which may has caused an early replicative senescence. Importantly, however, there were no significant differences between the two mouse strains, suggesting that UCP2-/-deficiency has no effect on the ageing of cultured PSC.

Fig. 5. Expression of α-SMA in cultured PSC from WT and UCP2-/-mice. A: PSC were grown on coverslips for 48 hours before subjected to α-SMA and DAPI staining (original magnification × 400). The photographs are typical of 6 independent experiments. B and C: cultured PSC were treated for 48 hours with TGF-β1 (5 ng/mL) as indicated, before expression of α-SMA and GAPDH (internal control) was analyzed by Western blotting. B: representative results for each mouse strain are shown. C: Normalized signal intensities are presented as mean±SE (n=16 separate cultures). There were no statistically significant differences between the experimental groups.

Fig. 6. Presence of lipid droplets in cultured PSC (original magnification ×400). PSC from WT mice (A, B) and UCP2-/-mice (C, D) were grown in primary culture on coverslips. After the indicated periods of time, intracellular lipid droplet (pointed out by arrows) were stained with oil red O. The photogaphs are typical for 6 independent samples per mouse strain and time point.

Fig. 7. Senescence of cultured PSC from WT and UCP2-/-mice. A: Exemplary photographs of PSC cultures (passage 1) from both mouse strains after SA β-Gal staining. B: SA β-Gal-positive cells of the indicated passage were determined on blinded samples. Data are presented as mean±SE (n≥6). *: P<0.01, versus passage 1 of the same mouse strain. There were no statistically significant differences between the two strains.

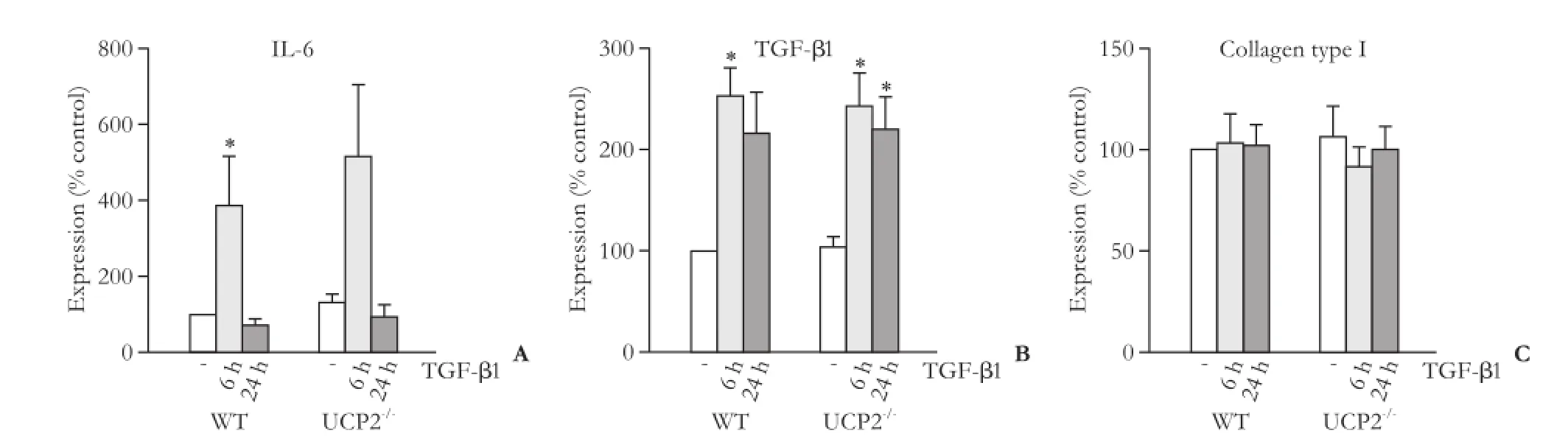

Fig. 8. mRNA expression of IL-6 (A), TGF-β1 (B) and collagen type 1 (C) in PSC from WT and UCP2-/-mice. The cells were treated with TGF-β1 (5 ng/mL) for the indicated periods of time. Data are presented as mean±SE (n≥8). *: P<0.01, versus untreated cultures of the same mouse strain. There were no statistically significant differences between the two strains at any time point.

Gene expression profiles of PSC from WT and UCP2-/-mice

We first checked that WT PSC expressed UCP2 whereas PSC from UCP2-/-mice did not, which was confirmed at the mRNA level (data not shown). Subsequently, we focused on two selected autocrine mediators of PSC activation, the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6[30]and TGF-β1.[7,8]The expression of both genes was induced by TGF-β1, although for IL-6 this effect reached statistical significance in WT cells only (Fig. 8A, B). Despite its overall role as a trigger of ECM synthesis, TGF-β1 did not alter the mRNA level of type I collagen (specifically, its chain α1; Fig. 8C). For all three genes, WT PSC and cells from UCP2-/-mice showed identical expression patterns without significant quantitative differences.

Discussion

PSCs are playing a dual role in pancreatic regeneration: on the one hand, they may contribute to normal wound healing after injury through the deposition of ECM; on the other hand an overshooting ECM production leads to pancreatic fibrosis.[2,3]Increased ROS levels have been shown to trigger PSC activation,[10,11]raising the possibility that a lack of the mitochondrial uncoupling protein UCP2 may have an impact on PSC function. Perhaps even more importantly, aged UCP2-/-mice display a prolonged pancreatic damage upon challenge with cerulein, suggesting that UCP2 is required for efficient organ regeneration.[16]To further elucidate UCP2 functions in the exocrine pancreatic compartment, we performed in vitro studies with PSC from WT and UCP2-/-mice. In order to reflect the experimental conditions of our previous in vivo studies,[16]the cells were isolated from 12 months old animals. The key findings of this investigation are firstly that UCP2-/-PSC proliferate at a lower rate than WT PSC and secondly that there was no correlation between growth rates and intracellular ROS levels, which did not differ between the two strains. Although these data do not exclude differences of ROS levels in subcellular compartments (specifically, the mitochondria), they still point to the possibility that mechanisms apart from lowering ROS contribute to the function of UCP2 in PSC proliferation. Indeed, the function of UCP2 as an effective uncoupling protein of the mitochondrial chain is currently under debate,[31]while other functions of UCP2 have been proposed that may be at least equally important, depending on the cellular context. Thus, at least in tumor cells UCP2 appears to directly influence metabolism by acting as an uniporter for pyruvate, which promotes pyruvate efflux from mitochondria, restricts mitochondrial respiration, and increases the rate of glycolysis.[32,33]UCP2 also displays anion transport and nucleotidebinding activities, which have been implicated in a further function of the protein: to promote the engulfment of apoptotic cells by increasing the phagocytic capacity of cells.[34,35]Furthermore, UCP2 deficiency has been shown to enhance the insulin secretory capacity of β cells in UCP2-/-mice.[23]It is therefore tempting to speculate that increased insulin levels might be associated with a downregulation of cell surface receptors for insulin and possibly other growth factors, providing a hypothetical explanation for the reduced growth rate of UCP2-/-PSC in the presence of serum. The relevance of these additional, or alternative, functions of UCP2 for PSC biology needs to be addressed in follow-up studies.

Most interestingly with respect to our findings, UCP2 inhibition has been shown to exert a synergistic antiproliferative effect with gemcitabine in pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells.[36]Furthermore, UCP2 expression is significantly higher in human pancreatic cancer samples than in the adjacent normal tissues, suggesting that UCP2 may promote tumor growth in this tumor type.[37]The role of PSC in pancreatic cancer is a matter of ongoing research activities. While a variety of previous studies has shown that PSC and PSC-derived ECM are promoting tumor

growth (e.g., by providing a barrier against immune cells and cytostatic drugs, as well as through mitogenic/antiapoptotic effects of secreted mediators),[2,3,38-42]two recent publications have indicated that stroma depletion may also have detrimental effects and even accelerate tumor spreading.[43,44]Based on our data, we hypothesize that inhibition of UCP2 will simultaneously hit stroma and cancer cells and thereby provide an attractive tool to study, in experimental models of pancreatic cancer, how a combined antifibrotic and tumor cell-directed therapy will affect tumor progression.

Apart from its role in proliferation, UCP2 seems to be dispensable for biological activities of PSC, specifically the exhibition of a myofibroblastic phenotype (as indicated by the loss of intracellular fat droplets and the formation of stress fiber networks), expression of type I collagen, IL-6 and TGF-β1, and the capability to undergo senescence: In none of these assays, statistically significant differences between WT PSC and PSC from UCP2-/-mice were observed.

Some interesting additional findings of this study are related to the effects of TGF-β1 on PSC of the two mouse strains which were used in our investigations. In accordance with previous studies,[45,46]TGF-β1 diminished DNA synthesis of WT PSC. In contrast, there was no significant antiproliferative effect of TGF-β1 on UCP2-/-PSC. This phenomenon might be related to the fact that the proliferation rate of UCP2-/-PSC was already reduced by the absence of the uncoupling protein. An additive growthinhibitory effect of the cytokine could not be detected.

Given the established profibrogenic activity of TGF-β1, the finding that TGF-β1 did not enhance expression of α-SMA and collagen type I in PSC of either of the two mouse strains was somewhat unexpected. However, it should be noted that the cells were fully activated already prior to TGF-β1 application, and themselves expressed the cytokine (Fig. 7B). In pilot experiments, we furthermore observed that rat PSC (which were frequently used in previous studies by us and others) retain their responsiveness to the profibrogenic effects of exogenous TGF-β1 over longer periods of culture time than mouse PSC (unpublished data).

In summary, our previous in vivo study[16]and the current in vitro experiments indicated that UCP2 may play an important role in PSC proliferation after acute pancreatitis. Open questions include ROS-independent functions of UCP2 in PSC, the mechanisms which underlie the age-dependency of the consequences of UCP2 deficiency and, most of all, the relevance of our findings to the human pancreas.

Acknowledgement: We gratefully acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Mrs. Katja Bergmann.

Contributors: MS and JR designed the research. MS, KSM and SA performed the experiments and analyzed the data. JR wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and contributed to the final manuscript. JR is the guarantor.

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (0315892A, GERONTOSYS program).

Ethical approval: All experiments were performed according to the guidelines of the local animal use and care committee (Landesamt für Landwirtschaft, Lebensmittelsicherheit und Fischerei Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Rostock, Germany).

Competing interest: No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Murtaugh LC, Keefe MD. Regeneration and repair of the exocrine pancreas. Annu Rev Physiol 2015;77:229-249.

2 Erkan M, Adler G, Apte MV, Bachem MG, Buchholz M, Detlefsen S, et al. StellaTUM: current consensus and discussion on pancreatic stellate cell research. Gut 2012;61:172-178.

3 Jaster R, Emmrich J. Crucial role of fibrogenesis in pancreatic diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2008;22:17-29.

4 Apte MV, Haber PS, Applegate TL, Norton ID, McCaughan GW, Korsten MA, et al. Periacinar stellate shaped cells in rat pancreas: identification, isolation, and culture. Gut 1998;43:128-133.

5 Bachem MG, Schneider E, Gross H, Weidenbach H, Schmid RM, Menke A, et al. Identification, culture, and characterization of pancreatic stellate cells in rats and humans. Gastroenterology 1998;115:421-432.

6 Kordes C, Sawitza I, G?tze S, H?ussinger D. Stellate cells from rat pancreas are stem cells and can contribute to liver regeneration. PLoS One 2012;7:e51878.

7 Schneider E, Schmid-Kotsas A, Zhao J, Weidenbach H, Schmid RM, Menke A, et al. Identification of mediators stimulating proliferation and matrix synthesis of rat pancreatic stellate cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2001;281:C532-543.

8 Apte MV, Haber PS, Darby SJ, Rodgers SC, McCaughan GW, Korsten MA, et al. Pancreatic stellate cells are activated by proinflammatory cytokines: implications for pancreatic fibrogenesis. Gut 1999;44:534-541.

9 Apte MV, Phillips PA, Fahmy RG, Darby SJ, Rodgers SC, Mc-Caughan GW, et al. Does alcohol directly stimulate pancreatic fibrogenesis? Studies with rat pancreatic stellate cells. Gastroenterology 2000;118:780-794.

10 Kikuta K, Masamune A, Satoh M, Suzuki N, Satoh K, Shimosegawa T. Hydrogen peroxide activates activator protein-1 and mitogen-activated protein kinases in pancreatic stellate cells. Mol Cell Biochem 2006;291:11-20.

11 Masamune A, Watanabe T, Kikuta K, Satoh K, Shimosegawa T. NADPH oxidase plays a crucial role in the activation of pancreatic stellate cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2008;294:G99-G108.

12 Zimmermann A, Gloor B, Kappeler A, Uhl W, Friess H, Büchler MW. Pancreatic stellate cells contribute to regeneration early after acute necrotising pancreatitis in humans. Gut 2002;51:574-578.

13 Ricquier D, Bouillaud F. The uncoupling protein homologues: UCP1, UCP2, UCP3, StUCP and AtUCP. Biochem J 2000;345:161-179.

14 Fleury C, Neverova M, Collins S, Raimbault S, Champigny O, Levi-Meyrueis C, et al. Uncoupling protein-2: a novel gene linked to obesity and hyperinsulinemia. Nat Genet 1997;15:269-272.

15 Gimeno RE, Dembski M, Weng X, Deng N, Shyjan AW, Gimeno CJ, et al. Cloning and characterization of an uncoupling protein homolog: a potential molecular mediator of human thermogenesis. Diabetes 1997;46:900-906.

16 Müller S, Kaiser H, Krüger B, Fitzner B, Lange F, Bock CN, et al. Age-dependent effects of UCP2 deficiency on experimental acute pancreatitis in mice. PLoS One 2014;9:e94494.

17 Segersv?rd R, Rippe C, Duplantier M, Herrington MK, Isaksson B, Adrian TE, et al. mRNA for pancreatic uncoupling protein 2 increases in two models of acute experimental pancreatitis in rats and mice. Cell Tissue Res 2005;320:251-258.

18 Skulachev VP. Uncoupling: new approaches to an old problem of bioenergetics. Biochim Biophys Acta 1998;1363:100-124.

19 Echtay KS, Roussel D, St-Pierre J, Jekabsons MB, Cadenas S, Stuart JA, et al. Superoxide activates mitochondrial uncoupling proteins. Nature 2002;415:96-99.

20 Boss O, Hagen T, Lowell BB. Uncoupling proteins 2 and 3: potential regulators of mitochondrial energy metabolism. Diabetes 2000;49:143-156.

21 Barazzoni R, Nair KS. Changes in uncoupling protein-2 and -3 expression in aging rat skeletal muscle, liver, and heart. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2001;280:E413-419.

22 Kuhla A, Trieglaff C, Vollmar B. Role of age and uncoupling protein-2 in oxidative stress, RAGE/AGE interaction and inflammatory liver injury. Exp Gerontol 2011;46:868-876.

23 Zhang CY, Baffy G, Perret P, Krauss S, Peroni O, Grujic D, et al. Uncoupling protein-2 negatively regulates insulin secretion and is a major link between obesity, beta cell dysfunction, and type 2 diabetes. Cell 2001;105:745-755.

24 Jaster R, Sparmann G, Emmrich J, Liebe S. Extracellular signal regulated kinases are key mediators of mitogenic signals in rat pancreatic stellate cells. Gut 2002;51:579-584.

25 Witteck L, Jaster R. Trametinib and dactolisib but not regorafenib exert antiproliferative effects on rat pancreatic stellate cells. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2015;14:642-650.

26 Rateitschak K, Karger A, Fitzner B, Lange F, Wolkenhauer O, Jaster R. Mathematical modelling of interferon-gamma signalling in pancreatic stellate cells reflects and predicts the dynamics of STAT1 pathway activity. Cell Signal 2010;22:97-105.

27 Sparmann G, Kruse ML, Hofmeister-Mielke N, Koczan D, Jaster R, Liebe S, et al. Bone marrow-derived pancreatic stellate cells in rats. Cell Res 2010;20:288-298.

28 Zhang CY, Parton LE, Ye CP, Krauss S, Shen R, Lin CT, et al. Genipin inhibits UCP2-mediated proton leak and acutely reverses obesity- and high glucose-induced beta cell dysfunction in isolated pancreatic islets. Cell Metab 2006;3:417-427.

29 Fitzner B, Müller S, Walther M, Fischer M, Engelmann R, Müller-Hilke B, et al. Senescence determines the fate of activated rat pancreatic stellate cells. J Cell Mol Med 2012;16:2620-2630.

30 Aoki H, Ohnishi H, Hama K, Shinozaki S, Kita H, Yamamoto H, et al. Existence of autocrine loop between interleukin-6 and transforming growth factor-beta1 in activated rat pancreatic stellate cells. J Cell Biochem 2006;99:221-228.

31 Donadelli M, Dando I, Fiorini C, Palmieri M. UCP2, a mitochondrial protein regulated at multiple levels. Cell Mol Life Sci 2014;71:1171-1190.

32 Baffy G. Uncoupling protein-2 and cancer. Mitochondrion 2010;10:243-252.

33 Donadelli M, Dando I, Dalla Pozza E, Palmieri M. Mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 and pancreatic cancer: a new potential target therapy. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:3232-3238.

34 Lee S, Moon H, Kim G, Cho JH, Lee DH, Ye MB, et al. Anion transport or nucleotide binding by Ucp2 is indispensable for Ucp2-mediated efferocytosis. Mol Cells 2015;38:657-662.

35 Park D, Han CZ, Elliott MR, Kinchen JM, Trampont PC, Das S, et al. Continued clearance of apoptotic cells critically depends on the phagocyte Ucp2 protein. Nature 2011;477:220-224.

36 Dalla Pozza E, Fiorini C, Dando I, Menegazzi M, Sgarbossa A, Costanzo C, et al. Role of mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 in cancer cell resistance to gemcitabine. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012;1823:1856-1863.

37 Li W, Nichols K, Nathan CA, Zhao Y. Mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 is up-regulated in human head and neck, skin, pancreatic, and prostate tumors. Cancer Biomark 2013;13:377-383.

38 Müerk?ster S, Wegehenkel K, Arlt A, Witt M, Sipos B, Kruse ML, et al. Tumor stroma interactions induce chemoresistance in pancreatic ductal carcinoma cells involving increased secretion and paracrine effects of nitric oxide and interleukin-1beta. Cancer Res 2004;64:1331-1337.

39 Bachem MG, Schünemann M, Ramadani M, Siech M, Beger H, Buck A, et al. Pancreatic carcinoma cells induce fibrosis by stimulating proliferation and matrix synthesis of stellate cells. Gastroenterology 2005;128:907-921.

40 Qian LW, Mizumoto K, Maehara N, Ohuchida K, Inadome N, Saimura M, et al. Co-cultivation of pancreatic cancer cells with orthotopic tumor-derived fibroblasts: fibroblasts stimulate tumor cell invasion via HGF secretion whereas cancer cells exert a minor regulative effect on fibroblasts HGF production. Cancer Lett 2003;190:105-112.

41 Armstrong T, Packham G, Murphy LB, Bateman AC, Conti JA, Fine DR, et al. Type I collagen promotes the malignant phenotype of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10:7427-7437.

42 Schneiderhan W, Diaz F, Fundel M, Zhou S, Siech M, Hasel C, et al. Pancreatic stellate cells are an important source of MMP-2 in human pancreatic cancer and accelerate tumor progression in a murine xenograft model and CAM assay. J Cell Sci 2007;120:512-519.

43 Rhim AD, Oberstein PE, Thomas DH, Mirek ET, Palermo CF, Sastra SA, et al. Stromal elements act to restrain, rather than support, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 2014;25:735-747.

44 ?zdemir BC, Pentcheva-Hoang T, Carstens JL, Zheng X, Wu CC, Simpson TR, et al. Depletion of carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and fibrosis induces immunosuppression and accelerates pancreas cancer with reduced survival. Cancer Cell 2014;25:719-734.

45 Kordes C, Brookmann S, H?ussinger D, Klonowski-Stumpe H. Differential and synergistic effects of platelet-derived growth factor-BB and transforming growth factor-beta1 on activated pancreatic stellate cells. Pancreas 2005;31:156-167.

46 Fitzner B, Brock P, Nechutova H, Glass A, Karopka T, Koczan D, et al. Inhibitory effects of interferon-gamma on activation of rat pancreatic stellate cells are mediated by STAT1 and involve down-regulation of CTGF expression. Cell Signal 2007;19:782-790.

Received March 7, 2016

Accepted after revision July 22, 2016

Author Affiliations: Department of Medicine II, Division of Gastroenterology, Rostock University Medical Center, E.-Heydemann-Str. 6, 18057 Rostock, Germany (Müller S, Klingbeil SM, Sandica A and Jaster R)

Robert Jaster, MD, Department of Medicine II, Division of Gastroenterology, Rostock University Medical Center, E. - Heydemann-Str. 6, 18057 Rostock, Germany (Tel: +49-381-4947349;

Fax: +49-381-4947482; Email: jaster@med.uni-rostock.de)

? 2016, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(16)60154-6

Published online November 4, 2016.

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2016年6期

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2016年6期

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumor in three patients

- Postoperative day one serum alanine aminotransferase does not predict patient morbidity and mortality after elective liver resection in non-cirrhotic patients

- Jagged1 and DLL4 expressions in benign and malignant pancreatic lesions and their clinicopathological significance

- Endoscopic bilateral stent-in-stent placement for malignant hilar obstruction using a large cell type stent

- Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma with bile duct tumor thrombus after R0 resection: a matched study

- Urgent ERCP for acute cholangitis reduces mortality and hospital stay in elderly and very elderly patients