Urgent ERCP for acute cholangitis reduces mortality and hospital stay in elderly and very elderly patients

Chan Sun Park, Hee Seok Jeong, Ki Bae Kim, Joung-Ho Han, Hee Bok Chae, Sei Jin Youn and Seon Mee Park

Cheongju, Korea

Urgent ERCP for acute cholangitis reduces mortality and hospital stay in elderly and very elderly patients

Chan Sun Park, Hee Seok Jeong, Ki Bae Kim, Joung-Ho Han, Hee Bok Chae, Sei Jin Youn and Seon Mee Park

Cheongju, Korea

BACKGROUND: Acute cholangitis in old people is a cause of mortality and prolonged hospital stay. We evaluated the effects of methods and timing of biliary drainage on the outcomes of acute cholangitis in elderly and very elderly patients.

METHODS: We analyzed 331 patients who were older than 75 years and were diagnosed with acute calculous cholangitis. They were admitted to our hospital from 2009 to 2014. Patients’ demographics, severity grading, methods and timing of biliary drainage, mortality, and hospital stay were retrospectively obtained from medical records. Clinical parameters and outcomes were compared between elderly (75-80 years, n=156) and very elderly (≥81 years, n=175) patients. We analyzed the effects of methods [none, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage, or failure] and timing (urgent or early) of biliary drainage on mortality and hospital stay in these patients.

RESULTS: Acute cholangitis in older patients manifested as atypical symptoms characterized as infrequent Charcot’s triad (4.2%) and comorbidity in one-third of the patients. Patients were graded as mild, moderate, and severe cholangitis in 104 (31.4%), 175 (52.9%), and 52 (15.7%), respectively. Urgent biliary drainage (≤24 hours) was performed for 80.5% (247/307) of patients. Very elderly patients tended to have more severe grades and were treated with sequential procedures of transient biliary drainage and stone removal at different sessions. Hospital stay was related to methods and timing of biliary drainage. Mortality was very low (1.5%) and not related to patient age but rather to the success or failure of biliary drainage and severity grading of the acute cholangitis.

CONCLUSIONS: The methods and timing used for biliary drainage and severity of cholangitis are the major determinants of mortality and hospital stay in elderly and very elderly patients with acute cholangitis. Urgent successful ERCP is mandatory for favorable prognosis in these patients.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2016;15:619-625)

acute cholangitis;

biliary drainage;

prognosis;

elderly;

very elderly

Introduction

Acute cholangitis varies in severity from a mild form, which improves with antibiotics alone, to a severe form, which needs urgent biliary drainage.[1]Biliary decompression is the most important treatment for acute obstructive cholangitis and it is best accomplished by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with complete stone removal or by endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) or stent placement.[1,2]Alternative methods are percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) or surgery; however, they carry higher morbidity and mortality risks.[1,3]

The timing of ERCP is controversial. Most patients with acute cholangitis improve after conservative man-

agement and an endoscopic procedure can be performed at a scheduled time during normal working hours.[4]Urgent ERCP should be performed for high-risk patients, including those with severe cholangitis,[4]elderly patients,[5]patients with a prolonged international normalized ratio (INR), and initial intensive care unit triage.[6]Delaying ERCP for more than 48 hours is associated with death, persistent organ failure, intensive care unit stays,[7,8]and/or an increased risk of 30-day readmission.[9]A recent study[10]reported that urgent ERCP is also helpful for shortening hospital stay for patients with mild to moderate acute cholangitis as compared to elective ERCP. Because ERCP is associated with risks of technical failure and procedure-related complications, and urgent ERCP is a burden in terms of utilization of resources, the necessity of urgent ERCP should be clearly defined.[6]

Acute cholangitis in elderly patients is different from that in younger individuals, with vague symptoms, higher rates of comorbidities, and a delayed diagnosis.[2]The prognosis is reported to include high morbidity, mortality, and prolonged hospital stay.[2,3,5,11]Recently, ERCP for acute obstructive cholangitis was shown to be effective and safe for elderly patients.[5,12,13]Whether age is considered a risk factor for complications from cholangitis is controversial. The revised severity grading of acute cholangitis in the updated Tokyo guidelines (TG13) included age greater than 75 years as a risk factor.[14]Because age is suggested as a risk factor in acute inflammatory diseases, the timing of biliary drainage might be different in elderly patients. However, the impact of the timing of ERCP on elderly patients has not been clearly defined.

We evaluated the prognosis of acute cholangitis in elderly (75-80 years) and very elderly (≥81 years) patients, considering the timing of the procedures and the methods used for biliary drainage. The primary aim of this study is to identify risk factors associated with mortality and hospital stay in elderly and very elderly patients with acute cholangitis. The secondary aim is to evaluate the impact of urgent ERCP on the outcomes of elderly and very elderly patients with acute cholangitis.

Methods

Patients

Three hundred thirty-one (29.4%) out of 1126 patients were enrolled in this study. Included patients were ≥75 years old and were treated under the diagnosis of acute calculous cholangitis from 2009 to 2014 at Chungbuk National University Hospital. Patients with malignant biliary obstruction and indwelling biliary stents were excluded. The mean age of the patients was 81.4±4.8 years (range 75-96) and the male to female ratio was 158:173. Thirty-four (10.3%) and 40 (12.1%) patients had a previously sphincterotomy and a cholecystectomy, respectively. We divided the patients into the elderly (75-80 years, mean age 77 years, 156 patients) and very elderly (≥81 years, mean age 85 years, 175 patients) groups. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and it was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chungbuk National University Hospital.

Methods

Patient demographics, presenting symptoms, severity, and outcomes were collected through retrospective review of medical records. Patient demographics included age, gender, and comorbidities. Comorbidities included liver cirrhosis, diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular accident, ischemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic renal failure. Presenting symptoms at admission included abdominal pain, fever, jaundice, altered mental status, and shock. Laboratory data included white blood cell count, platelet count, prothrombin time, and alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, albumin, and total bilirubin levels.

The definite diagnosis of acute cholangitis was based on the Tokyo guidelines, namely, evidence of systemic inflammation (fever and/or shaking, chills, or laboratory data), cholestasis (jaundice or laboratory data), and imaging data of the biliary tract (dilatation, stricture, stone, or stent).[15]The severity was graded as mild, moderate, or severe following the revised Tokyo guidelines.[15]Third generation cephalosporin was administered before causative organisms were isolated. Metronidazole was added to the treatment for patients with severe cholangitis. Methods of biliary drainage included ERCP, PTBD, surgery, none, or failed. The timing of biliary drainage was determined by the endoscopists’ discretion. Urgent ERCP was performed for patients with severe cholangitis. Patients with mild to moderate cholangitis underwent ERCP during normal working hours depending on arrival time at the hospital. Timing of biliary drainage after admission was recorded and analyzed as urgent (within 24 hours) and early (24-48 hours) drainage. We performed ERCP as our first choice and PTBD for patients with anatomical derangement or failed ERCP. ERCP was performed in patients with oxygen saturation >90% and with a systolic blood pressure >90 mmHg by using oxygen supplement and inotrope administration. All patients were stable enough to undergo ERCP procedures and no serious adverse events occurred. Complete stone removal or temporary placement of ENBD or biliary stents were performed at the endoscopists’ discretion. Temporary biliary decompression was done for patients

who could not tolerate a prolonged procedure. Complications related to ERCP were evaluated.[16,17]Mortality was defined as patients who died within 30 days after admission irrespective of etiology. Outcomes were hospital stay and mortality within 30 days.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 16.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used to analyze the data. The differences between groups were evaluated by using a Chi-square test for categorical data and a Student’s t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test for non-categorical data. The relationship between timing of biliary drainage and hospital stay was analyzed with Pearson’s test. Logistic regression analysis was conducted on the factors that may have affected mortality for severity grading and success or failure of biliary drainage. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics of acute cholangitis

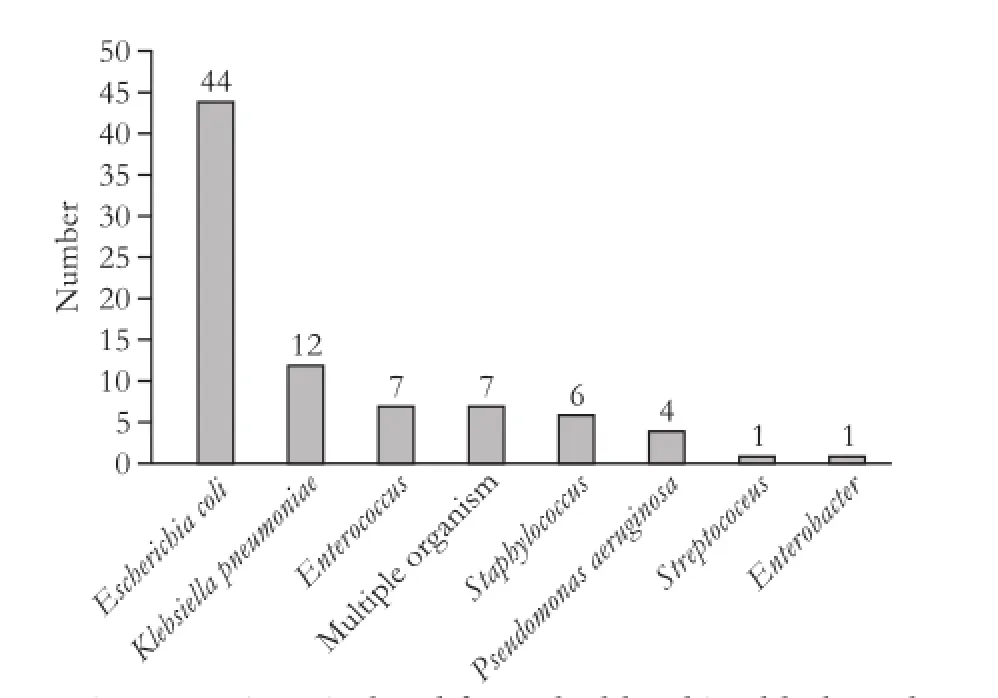

Presenting symptoms at admission were abdominal pain, fever, and jaundice in 284 patients (85.8%), 147 patients (44.4%), and 35 patients (10.6%), respectively. Charcot’ s triad was seen in 14 patients (4.2%), and hypotension or mental confusion was seen in 11 (3.3%) and 10 (3.0%), respectively. Thirty percent of patients had more than one comorbidity; diabetes mellitus in 40 (12.1%), stroke in 27 (8.2%), ischemic heart disease in 27 (8.2%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in 13 (3.9%), and chronic renal failure in 9 (2.7%). Laboratory data revealed leukocytosis or leukopenia (>12×1012/L or <4.0 × 1012/L) in 27 patients (8.2%), thrombocytopenia (<100 × 1012/L) in 35 (10.6%), hypoalbuminemia (<2.5 g/dL) in 21 (6.3%), and hyperbilirubinemia (>5.0 mg/dL) in 58 (17.5%). Mild, moderate, and severe cholangitis were diagnosed in 104 (31.4%), 175 (52.9%), and 52 (15.7%) patients, respectively. The severity of acute cholangitis tended to be graver in very elderly patients than elderly patients (P=0.028). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (P=0.044) and chronic renal failure (P=0.015) were more prevalent in elderly patients (Table 1). Causative organisms, isolated from 82 (29.0%) out of 283 patients with blood cultures, were dominant for Gram-negative rods including Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae (Fig. 1). The detection rates of bacteremia increased according to severity grades (mild 16.7% vs moderate 30.1% vs severe 45.1%, P=0.002). Patients with bacteremia had the longer hospital stay than those without it (8.7 ±5.0 vs 7.0±4.0 days, P=0.003).

Methods and timing of biliary decompression

Biliary drainage was done with ERCP in 284 (85.8%) patients and with PTBD in 23 (6.9%). Mean timing of ERCP and PTBD after admission were 19 and 43 hours, respectively. PTBD was performed for 7 patients when ERCP failed and 16 patients for deranged anatomy.

Twenty-four patients were treated with antibiotics only; there was no evidence of persistent biliary obstruction in 18 patients and drainage failure occurred in 6 patients (technical failure in 1 patient, disagreement about procedures in 3, and not tolerable conditions in 2). The technical success rate of ERCP was 96.9% (284/293). Selective bile duct cannulation was failed in 9 patients.Repeated ERCP was performed in 77 out of 284 patients (27.1%) consisting of first a temporary ENBD catheter or plastic stent followed by complete stone clearance by repeated ERCP after a mean of 52 hours. Numbers of ERCP sessions were not different between elderly and very elderly patients. Complications related to ERCP were acute pancreatitis in 18 (6.3%) patients and bleeding in 7 (2.5%), which improved after conservative management and were not different between the two groups. Mean hospital stay and mortality were not different between the groups (Table 2).

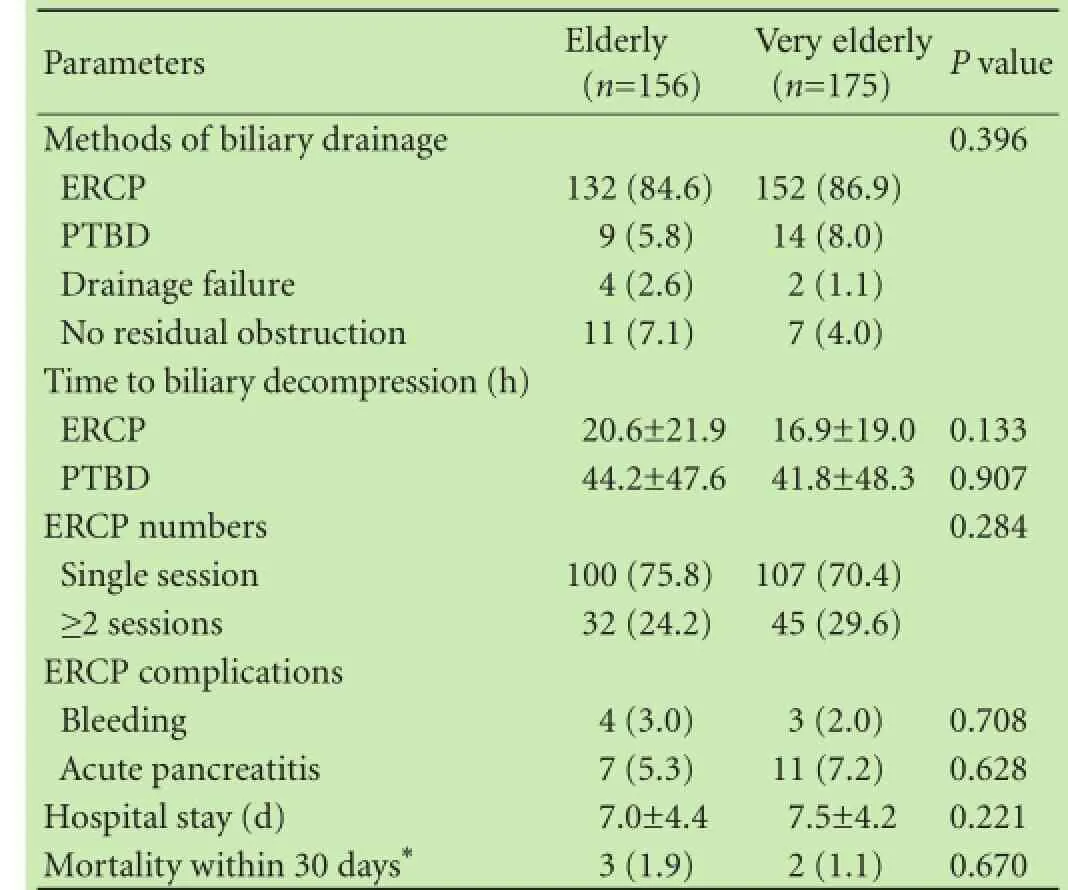

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of elderly and very elderly patients with acute cholangitis (n, %)

Fig. 1. Microorganisms isolated from the blood in elderly and very elderly patients with acute cholangitis.

Hospital stay and mortality

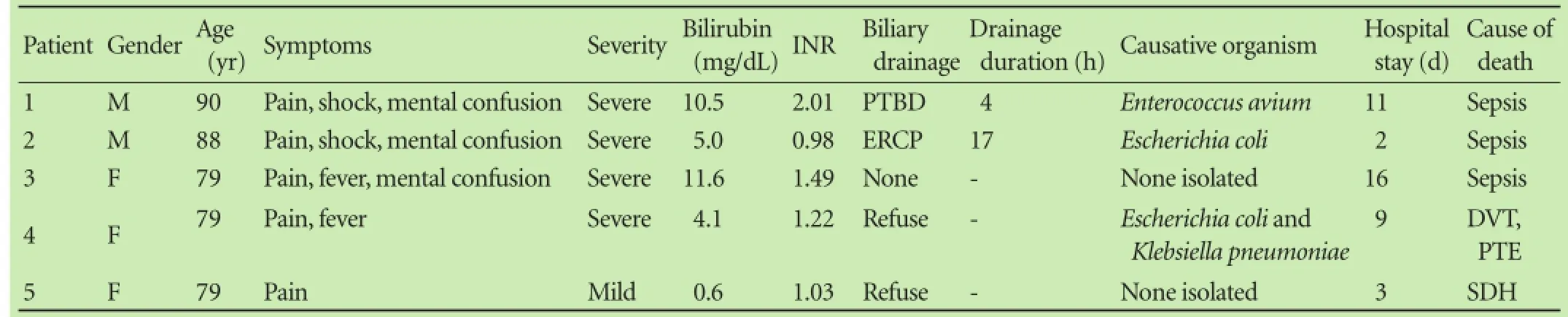

Five patients (1.5%) died and one was referred to another hospital. The causes of mortality were septic shock in three patients and pulmonary thromboembolism and subdural hemorrhage in one patient each. Among the five who died, four patients had severe cholangitis and three had failed biliary drainage because of two patients’refusal of the procedure due to pulmonary thromboembolism or subdural hemorrhage in one patient each and one patient with poor general condition (Table 3).

Table 2. Methods and timing of biliary drainage for acute cholangitis in elderly and very elderly patients (n, %)

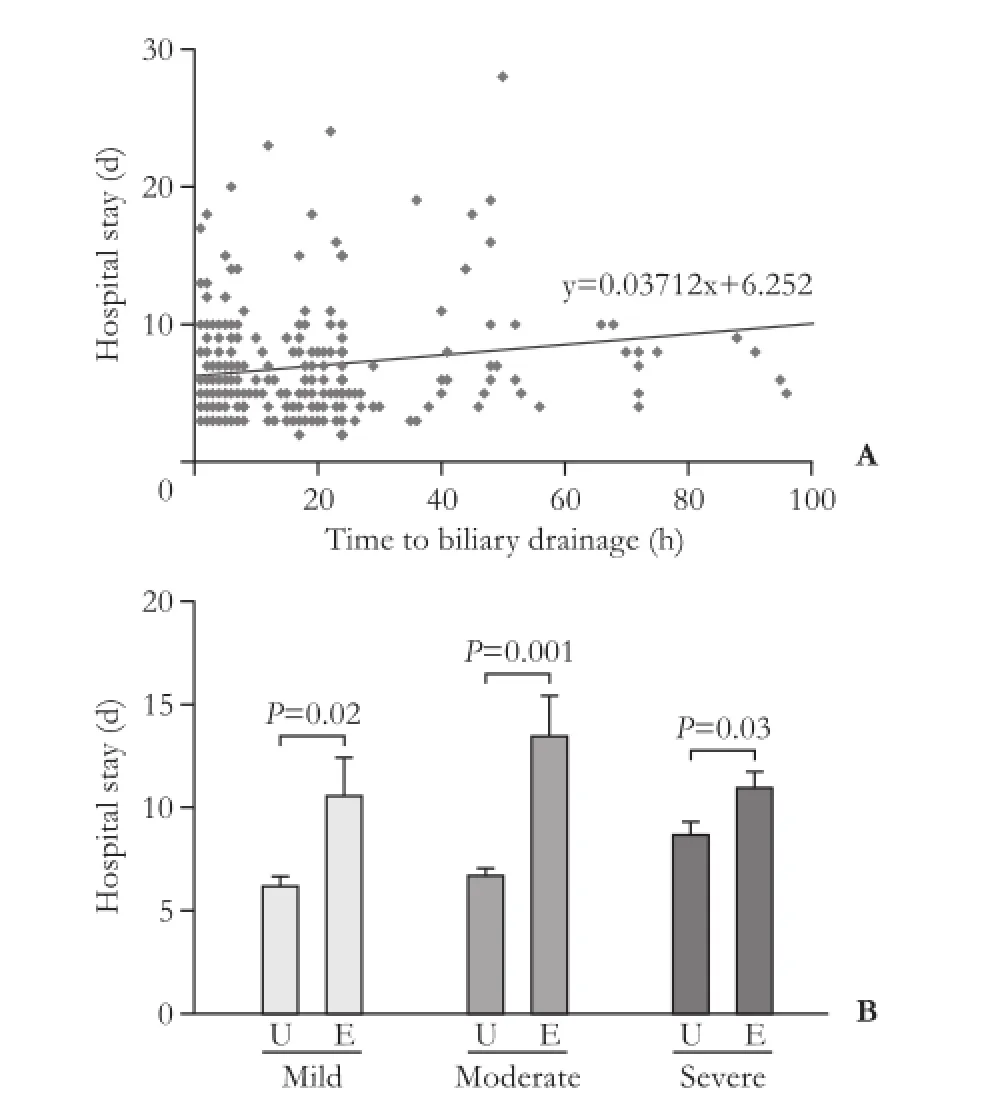

Fig. 2. Hospital stay according to timing of biliary drainage. A: correlation between timing of biliary drainage and hospital stay (P=0.001); B: comparison of hospital stay according to urgent or early biliary drainage in mild, moderate, and severe acute cholangitis. Urgent biliary drainage is related to shorter hospital day in mild (6.2±4.1 vs 10.6±4.2 days, P=0.02), moderate (6.7±3.6 vs 13.5±6.6 days, P=0.001), and severe (8.7±4.0 vs 11.0±1.6 days, P=0.03) acute cholangitis. U: urgent biliary drainage; E: early biliary drainage.

Table 3. Patients profiles with mortality

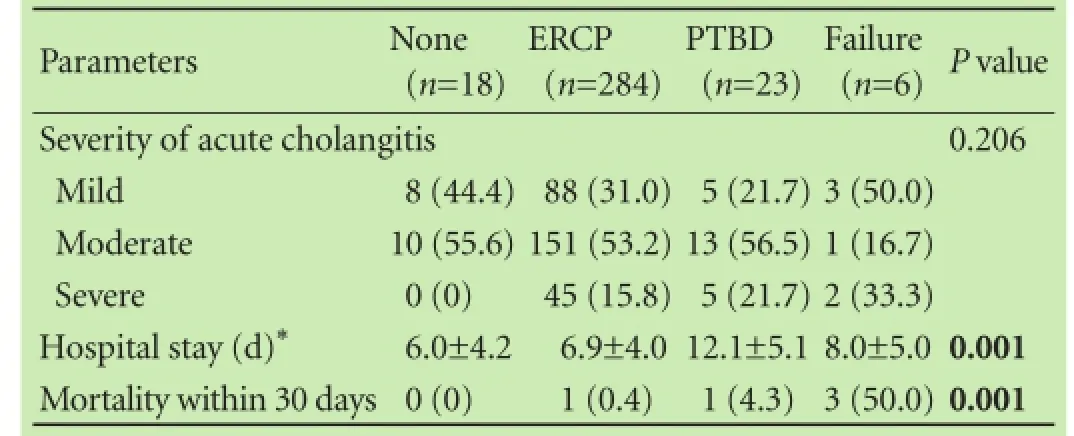

Table 4. Severity and outcomes of acute cholangitis according to methods of biliary drainage (n, %)

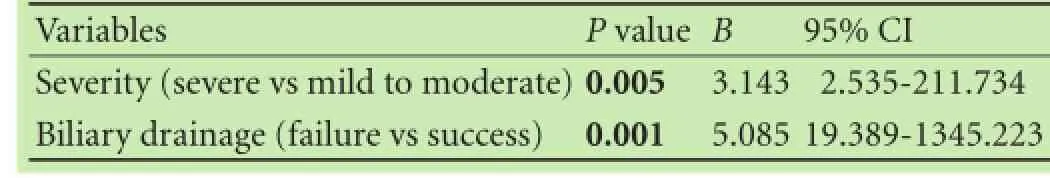

Table 5. Univariate analysis for parameters related with 30-day mortality in the elderly and very elderly patients with acute cholangitis

The type of biliary drainage procedure [none (n=18), ERCP (n=284), PTBD (n=23), and failure (n=6)] was related to mortality (P=0.001) and hospital stay (P=0.001). Biliary drainage with PTBD was associated with prolonged hospital stay (Table 4). Mean hospital stay was 7.3 days, which was related to the timing of biliary drainage (Fig. 2A, P=0.001). Hospital stay for urgent (n=247) and early biliary drainage (n=60) were 7.0±3.7 and 8.8±5.8 days, respectively (P=0.02). Urgent biliary drainage was associated with shorter hospital stay in all patients irrespective of severity (Fig. 2B). Mortality was related to the severity of acute cholangitis (severe vs mild to moderate, P=0.005) and success or failure of biliary drainage (failure vs success, P=0.001) by logistic regression analysis (Table 5).

Discussion

This study demonstrated that urgent ERCP for acute cholangitis in elderly and very elderly patients showed favorable outcomes. All patients except six recovered from acute cholangitis. Urgent successful biliary drainage with ERCP is related to lower mortality and shorter hospital stay for acute cholangitis in older patients. There were no differences in mortality or hospital stay between elderly and very elderly patients.

Acute cholangitis in older people is characterized by vague symptoms, delayed diagnosis, comorbidities, and more severe grades than in younger patients. Charcot’ s triad was manifested in only 4.2% of patients in this study, which was a lower level than recorded for general population in a previous study.[15]Laboratory data and imaging tests should be considered for the diagnosis in addition to symptoms.[2]Tokyo guidelines 2013 (TG13) recommends that acute cholangitis should be considered in patients with biliary stones with only one symptom without evidence of inflammation.[14]

Accumulating evidence shows that patients ≥75 years with cholangitis have higher morbidity and mortality.[2,3,5,11]Old age (≥75 years) is one parameter for a moderate grade of acute cholangitis according to TG13.[15]Our study found that severe cholangitis is more common in very elderly patients than elderly patients, similar to the findings of previous studies.[18,19]We also demonstrated that ERCP can be performed safely in all patients irrespective of age, which is consistent with the results of a previous study.[18]Comorbidities were present in 30% of our patients. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic renal failure occurred more frequently in elderly than in very elderly patients in this study. A previous study[20]has reported that comorbidities were more frequent in very elderly than in elderly patients.

Causative organisms for acute cholangitis are Gramnegative rods, found in patients of all ages in a previous study.[21]The most predominant organisms are Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. All of our cases had acute calculous cholangitis without indwelling biliary devices. The organisms isolated from the blood were similar to those from community acquired bacteremia.[22]Our study found that patients with bacteremia had prolonged hospital stay and severe grades, which is consistent with a previous study that reported that bacteremia was a risk factor for persistent organ failure.[8]

The methods used for biliary drainage and success or failure are the most important factors for mortality and hospital stay in this study. Several studies[1,3]have reported that biliary drainage via ERCP is the safest and most effective for old patients compared to PTBD or surgery. TG13 recommends that endoscopic drainage should be the first choice treatment for biliary decompression.[4]We performed ERCP as a first choice and PTBD was only performed for patients with surgically altered anatomy or with a failed ERCP.

Temporary biliary drainage with ENBD or a biliary stent was performed in 77 out of 284 patients (27.1%) with a poor general condition at the endoscopists’ discretion. A brief procedure for biliary drainage is well tolerated by patients in poor general condition or very elderly patients.[18,20]Many reports, including this study, have shown that ENBD is very effective and safe in nonagenarian (≥90 years) patients with unstable hemodynamics.[23,24]However, hospital stay were longer for patients with two-stage treatment than for those with a single-stage procedure

(9.0±3.8 vs 6.2±3.8 days, P<0.0001). A recent study[25]reported that a single-stage endoscopic procedure was effective and safe for mild to moderate acute cholangitis.

Timing of biliary drainage is an important issue for management of acute cholangitis. Many studies[4-10]have demonstrated that “the earlier, the better.” They indicate that urgent biliary drainage is necessary in severe acute cholangitis.[4]Another study showed that urgent ERCP reduced hospital stay for cases with mild to moderate calculous acute cholangitis.[10]A recent study[8]revealed a significant association between delayed ERCP (>48 hours) and persistent organ failure (odds ratio=3.1), with every 1 day delay in ERCP predicting a 17% risk increase. In addition, it was reported that urgent biliary drainage is necessary for people more than 75 years old.[5]The current study also demonstrated that urgent biliary drainage is related to shorter hospital stay in all cases of acute cholangitis irrespective of severity. Mean hospital stay in this study was 7.3 days, which was similar to or shorter than that reported by previous studies.[7,20]

Mortality was related to grading of severity and unsuccessful biliary drainage, but not to age alone. This is consistent with previous studies.[7,18,26]This study showed that mortality in elderly and very elderly patients was 1.5%, which is very low compared to the 5%-10% in other studies.[8,27]The causes of the favorable outcomes may be due to performing urgent successful biliary drainage with a brief procedure time. We treated 233 out of 284 patients (82.0%) with urgent ERCP and only nine were not successful for biliary decompression.

Our complication rate related to ERCP was 8.5%, and it was not different between elderly and very elderly patients, which is consistent with the previous study.[17]A recent study[24]has revealed that ERCP-induced acute pancreatitis is rare in older patients because of pancreatic atrophy and fibrosis. Bleeding during or after ERCP occurs frequently because of the frequent use of antithrombotic agents in older patients.[28,29]

However, because this was a retrospective study, the timing of biliary drainage and patient’s discharge were not determined by strict criteria but by the doctor’s discretion, and this is a limitation of the study.

In conclusion, acute cholangitis in elderly and very elderly patients can be diagnosed based on laboratory and imaging data in conjunction with the atypical clinical presentation. Urgent biliary drainage with ERCP using a brief procedure time is necessary for a favorable prognosis, especially in patients with severe grades.

Contributors: PCS and JHS proposed the study. PCS and PSM performed research and wrote the draft. KKB, HJH, CHB and YSJ collected and analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. PSM is the guarantor.

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chungbuk National University Hospital.

Competing interest: No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Lai EC, Mok FP, Tan ES, Lo CM, Fan ST, You KT, et al. Endoscopic biliary drainage for severe acute cholangitis. N Engl J Med 1992;326:1582-1586.

2 Rahman SH, Larvin M, McMahon MJ, Thompson D. Clinical presentation and delayed treatment of cholangitis in older people. Dig Dis Sci 2005;50:2207-2210.

3 Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Treatment of acute cholangitis due to choledocholithiasis in elderly and younger patients. Arch Surg 1997;132:1129-1133.

4 Miura F, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Solomkin JS, Pitt HA, Gouma DJ, et al. TG13 flowchart for the management of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2013;20:47-54.

5 Pang YY, Chun YA. Predictors for emergency biliary decompression in acute cholangitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;18:727-731.

6 Tabibian JH, Kane SV. Letter: acute cholangitis--understanding predictors of outcome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;42:777.

7 Khashab MA, Tariq A, Tariq U, Kim K, Ponor L, Lennon AM, et al. Delayed and unsuccessful endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography are associated with worse outcomes in patients with acute cholangitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:1157-1161.

8 Lee F, Ohanian E, Rheem J, Laine L, Che K, Kim JJ. Delayed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography is associated with persistent organ failure in hospitalised patients with acute cholangitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;42:212-220.

9 Navaneethan U, Gutierrez NG, Jegadeesan R, Venkatesh PG, Butt M, Sanaka MR, et al. Delay in performing ERCP and adverse events increase the 30-day readmission risk in patients with acute cholangitis. Gastrointest Endosc 2013;78:81-90.

10 Jang SE, Park SW, Lee BS, Shin CM, Lee SH, Kim JW, et al. Management for CBD stone-related mild to moderate acute cholangitis: urgent versus elective ERCP. Dig Dis Sci 2013;58: 2082-2087.

11 Nishikawa T, Tsuyuguchi T, Sakai Y, Sugiyama H, Sakamoto D, Nakamura M, et al. Old age is associated with increased severity of complications in endoscopic biliary stone removal. Dig Endosc 2014;26:569-576.

12 Fritz E, Kirchgatterer A, Hubner D, Aschl G, Hinterreiter M, Stadler B, et al. ERCP is safe and effective in patients 80 years of age and older compared with younger patients. Gastrointest Endosc 2006;64:899-905.

13 Ashton CE, McNabb WR, Wilkinson ML, Lewis RR. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in elderly patients. Age Ageing 1998;27:683-688.

14 Itoi T, Tsuyuguchi T, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Pitt HA, Kim MH, et al. TG13 indications and techniques for biliary drain-

age in acute cholangitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2013;20:71-80.

15 Kiriyama S, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Solomkin JS, Mayumi T, Pitt HA, et al. New diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute cholangitis in revised Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2012;19:548-556.

16 Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, et al. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med 1996;335:909-918.

17 Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc 1991;37:383-393.

18 Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile duct stones in patients 90 years of age and older. Gastrointest Endosc 2000;52:187-191.

19 Agarwal N, Sharma BC, Sarin SK. Endoscopic management of acute cholangitis in elderly patients. World J Gastroenterol 2006;12:6551-6555.

20 Kim JE, Cha BH, Lee SH, Park YS, Kim JW, Jeong SH, et al. Safety and efficacy of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatograpy in very elderly patients. Korean J Gastroenterol 2011;57:237-242.

21 Goo JC, Seong MH, Shim YK, Lee HS, Han JH, Shin KS, et al. Extended spectrum-β-lactamase or carbapenemase producing bacteria isolated from patients with acute cholangitis. Clin Endosc 2012;45:155-160.

22 Esposito AL, Gleckman RA, Cram S, Crowley M, McCabe F, Drapkin MS. Community-acquired bacteremia in the elderly: analysis of one hundred consecutive episodes. J Am Geriatr Soc 1980;28:315-319.

23 Sharma BC, Kumar R, Agarwal N, Sarin SK. Endoscopic biliary drainage by nasobiliary drain or by stent placement in patients with acute cholangitis. Endoscopy 2005;37:439-443.

24 Lee JK, Lee SH, Kang BK, Kim JH, Koh MS, Yang CH, et al. Is it necessary to insert a nasobiliary drainage tube routinely after endoscopic clearance of the common bile duct in patients with choledocholithiasis-induced cholangitis? A prospective, randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;71:105-110.

25 Eto K, Kawakami H, Haba S, Yamato H, Okuda T, Yane K, et al. Single-stage endoscopic treatment for mild to moderate acute cholangitis associated with choledocholithiasis: a multicenter, non-randomized, open-label and exploratory clinical trial. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2015;22:825-830.

26 Siegel JH, Kasmin FE. Biliary tract diseases in the elderly: management and outcomes. Gut 1997;41:433-435.

27 García-Alonso FJ, de Lucas Gallego M, Bonillo Cambrodón D, Algaba A, de la Poza G, Martín-Mateos RM, et al. Gallstonerelated disease in the elderly: is there room for improvement? Dig Dis Sci 2015;60:1770-1777.

28 Ueki T, Otani K, Fujimura N, Shimizu A, Otsuka Y, Kawamoto K, et al. Comparison between emergency and elective endoscopic sphincterotomy in patients with acute cholangitis due to choledocholithiasis: is emergency endoscopic sphincterotomy safe? J Gastroenterol 2009;44:1080-1088.

29 Lukens FJ, Howell DA, Upender S, Sheth SG, Jafri SM. ERCP in the very elderly: outcomes among patients older than eighty. Dig Dis Sci 2010;55:847-851.

Received November 18, 2015

Accepted after revision June 15, 2016

Author Affiliations: Department of Internal Medicine, Chungbuk National University College of Medicine, 1 Chungdae-ro, Seowon-gu, Cheongju 28644, Korea (Park CS, Jeong HS, Kim KB, Han JH, Chae HB, Youn SJ and Park SM)

Seon Mee Park, MD, PhD, Department of Internal Medicine, Chungbuk National University College of Medicine, 1 Chungdae-ro, Seowon-gu, Cheongju 28644, Korea (Tel: +82-43-269-6019; Fax: +82-43-273-3252; Email: smpark@chungbuk.ac.kr)

? 2016, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(16)60130-3

Published online September 13, 2016.

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2016年6期

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2016年6期

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumor in three patients

- Postoperative day one serum alanine aminotransferase does not predict patient morbidity and mortality after elective liver resection in non-cirrhotic patients

- Uncoupling protein 2 deficiency reduces proliferative capacity of murine pancreatic stellate cells

- Jagged1 and DLL4 expressions in benign and malignant pancreatic lesions and their clinicopathological significance

- Endoscopic bilateral stent-in-stent placement for malignant hilar obstruction using a large cell type stent

- Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma with bile duct tumor thrombus after R0 resection: a matched study