Training medical undergraduates in the core disciplines of community medicine through community postings – an experience from India

Hemant Deepak Shewade, Chinnakali Palanivel, Kathiresan Jeyashree

1. Department of Community Medicine, Indira Gandhi Medical College and Research Institute,Puducherry, India

2. Department of Community Medicine, Velammal Medical College Hospital amp; Research Institute, Madurai, India

Training medical undergraduates in the core disciplines of community medicine through community postings – an experience from India

Hemant Deepak Shewade1,a, Chinnakali Palanivel1,b, Kathiresan Jeyashree2

1. Department of Community Medicine, Indira Gandhi Medical College and Research Institute,Puducherry, India

2. Department of Community Medicine, Velammal Medical College Hospital amp; Research Institute, Madurai, India

Objective:Family medicine, epidemiology, health management and health promotion are the core disciplines of community medicine. In this paper, we discuss the development of a community posting program within the framework of community medicine core disciplines at a primary health centre attached to a teaching hospital in Puducherry, India.

Methods:This is a process documentation of our experience.

Results:There were some shortcomings which revolved around the central theme that postings were conducted with department in the teaching hospital as the focal point, not the primary health centre (PHC). To address the shortcomings, we made some changes in the existing community posting program in 2013. Student feedback aimed at Kirkpatrick level 1 (satisfaction)evaluation revealed that they appreciated the benefits of having the posting with PHC as the focal point. Feedback recommended some further changes in the community posting which could be addressed through complete administrative control of the primary health centre as urban health and training center of the teaching hospital; and also through practice of core disciplines of community medicine by faculty of community medicine.

Conclusion:It is important to introduce the medical undergraduates to the core disciplines of community medicine early through community postings. Community postings should be conducted with primary health centre or urban health and training centre as the focal point.

Family medicine; community posting; clinical posting; community-based medical education; undergraduate medical education; epidemiology; health management; health promotion

Background

The concept of community medicine started in South Africa in the 1940s when the need was felt to incorporate family medicine into preventive and social medicine to deliver primary health care [1]. Community medicine has components of both family medicine and public health [2, 3]. Family medicine provides continuing and comprehensive health care for the individual and the family, emphasizing disease prevention and promotion [4]. The public health components of community medicine are epidemiology, health promotion, and health management.

Each core discipline of community medicine has a role to play in the development of physcians. Understanding family medicine will make the graduate a better family physician who is able to address biological and social determinants of health and not focus on the individual alone. Health management skills will aid him/her in managing a primary health center (PHC) as a medical officer. Sensitization to health promotion will help him/her in primordial and primary prevention in his/her PHC area. Knowledge of and skills in epidemiology will enable the graduate to become a researcher who will effectively use observations and knowledge gained from the community to inform health care planning and implementation. The aim is to develop a physician who, besides possessing clinical skills,can effectively deliver primary health care and manage a PHC.

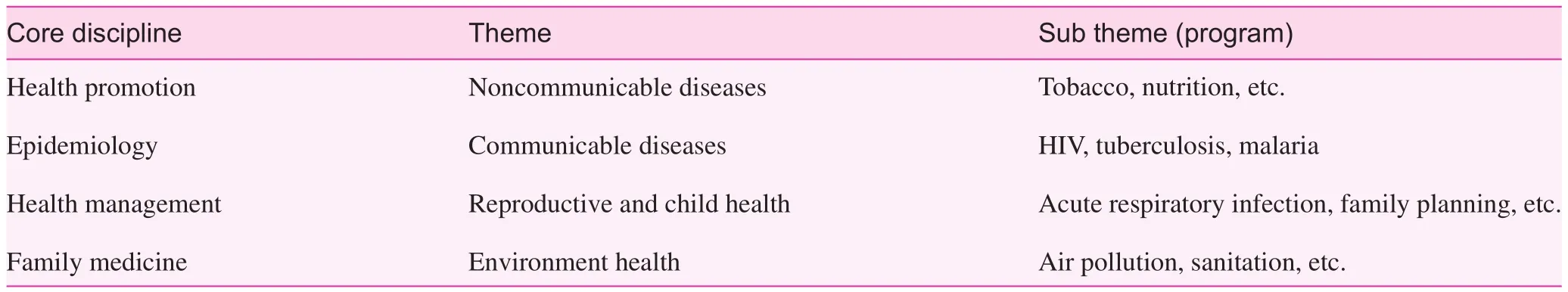

Worldwide, there are three general contexts in which community-based medical education is provided: programs that are developed primarily to provide services to an underserved community; programs that have a research focus; and programs that have (clinical) training of students as their primary goal [5]. In India, departments of community medicine in teaching hospitals provide community-based medical education through urban health and training centers (UHTCs) and rural health and training centers (RHTCs) with training of students as their primary goal. The primary role of community medicine specialists is that of health service provision, teaching/training, and research through UHTCs and RHTCs [6]. In addition to their primary role, community medicine specialists can choose one or more of the four core subspecialties/core disciplines of community medicine [2] (Table 1).

Suggestions for systematic changes of the status quo in Indian medical education have been documented [7–10]. One of the suggestions has been to produce medical graduates who are socially motivated for community health services [10].Community-based medical education for undergraduates may be imparted through clinical postings in community medicine(community postings) and implementation of the skills during medical internship in UHTCs and RHTCs.

This is a process documentation of our experience of developing a community posting program for undergraduate medical education based on a conceptual framework consisting of core disciplines of community medicine. The lessons learned may be used by other teaching hospitals to develop or improve their programs for undergraduates.

Conceptual framework of community posting

Indira Gandhi Medical College and Research Institute,Puducherry, India, is a teaching hospital established by the Government of Puducherry, with medical undergraduate(MBBS) students enrolled since 2010. As per Medical Council of India guidelines, throughout their MBBS degree, students undergo 12 weeks of community posting under Department of Community Medicine: 4 weeks in each of the third, fourth,and sixth semesters (3 hours each day). The Department of Community Medicine is located in and is part of the teaching hospital. A government PHC (located in an urban area) is attached to the Department of Community Medicine to serve as a peripheral health center to conduct MBBS teaching/training (approx. 40 students per posting). The PHC is 4 km from the teaching hospital.

Under family medicine, students are involved in clinical–psychosocial case reviews of common illnesses and diseases of public health importance. Students are expected to work on a family having illness or disease of public health importance with focus on the index case. In the first posting (third semester) students are expected to perform history taking and examination and arrive at a clinical and family diagnosis. In the second posting (fourth semester), students are trained tomanage the above-mentioned conditions/diseases as a primary health care provider following standard treatment guidelines.Also, the national health program related to the illness or disease of the index case is discussed in the final community posting (sixth semester).

Table 1. Core disciplines of community medicine [2]

Alongside clinical–psychosocial case reviews, students are involved in planning and conducting epidemiological exercises/research projects on relevant public health topics during their community postings. Epidemiological exercises can be community based or done at the PHC itself. This way, the students develop practical knowledge pertaining to research methods, epidemiology, and biostatistics. The students attempt to translate the results of the epidemiological exercises to the benefit of the community. This could be organizing a health education session (health promotion) in the form of a role play/health talk in the community or interaction with significant members of the community to share the results and way forward.

Under health management, students visit an antenatal clinic, an immunization clinic, and an anganwadi center (first posting) and a designated microscopy center under the national tuberculosis program and an integrated counseling and testing center (second posting) under the national AIDS program.The students understand the functioning and management of a PHC and also the implementation of various national health programs. The PHC-based epidemiological exercise and case discussion in the third community posting also aids in this process.

Shortcomings of the community posting program

Earlier, students were sent directly to the field practice area of the PHC for a clinical–psychosocial case within a family or an epidemiological exercise or health education session in the community. Students visited the PHC only during visits to the designated sputum microscopy center. Students were given a case (to be taken in field) and were expected to present it before the faculty and students of the department located in the teaching hospital, not in the PHC. Similarly, presentations were made on the epidemiological exercise, health management, and health-promotion-related exercises in the department. Assessment was also coupled with presentations. Our experience with previous clinical postings in the department taught us that these exercises lacked a community orientation.This process did not enhance students’ complete learning in the context of the PHC and the community. Active interaction with PHC staff and community-based learning were missing.Discussions were predominantly focused on the index case and the views of PHC staff about the case were missing. Faculty involvement in training was passive. We felt that interaction and discussion was required on a daily basis. Assessment needed to be dealt with separately at the end of the posting.

The revised community posting program

To overcome the shortcomings, we revised the community posting program in 2013, maintaining the need to streamline the program within the conceptual framework (community medicine core disciplines). First, community postings were conducted with the PHC and not the department in the teaching hospital as the focal point. Second, daily discussion for 1 hour (final hour of 3 hours allotted to community postings)related to the activity in the first two hours was required at the PHC itself. This required the faculty member in charge of the community posting to be present at the PHC. Third, there was a need to have separate sessions for assessment at the end of the posting and not to have them with routine discussions and presentations. Fourth, students required some reference material in addition to their textbook and clarity of what was expected of them at the beginning of the community posting.

In 2013 we implemented this revised community posting program for sixth-semester students (n=40) and a faculty member was appointed in charge. On a typical community posting day at the PHC, students travelled to the PHC by institution bus at 10 am and returned to the teaching hospital by 1 pm. The faculty member in charge accompanied them daily. The schedule was prepared such that each student was exposed to each activity in the areas of family medicine,health management, epidemiology, and health promotion in the first two hours, followed by discussion on the same activities in the last hour.

We encouraged the students to form an online group so that soft copy of study material could be shared with all at one go. Faculty, at the beginning of the posting, e-mailed relevant study material, such as the timetable, standard treatment guidelines, national health program guidelines/documents,basics in epidemiology/biostatistics, and must know and desirable to know (take-home) points.

In the last week of the community posting, students were assessed through case presentations to faculty, an epidemiological exercise presentation in the form of a PowerPoint presentation, and response stations.

Feedback from students

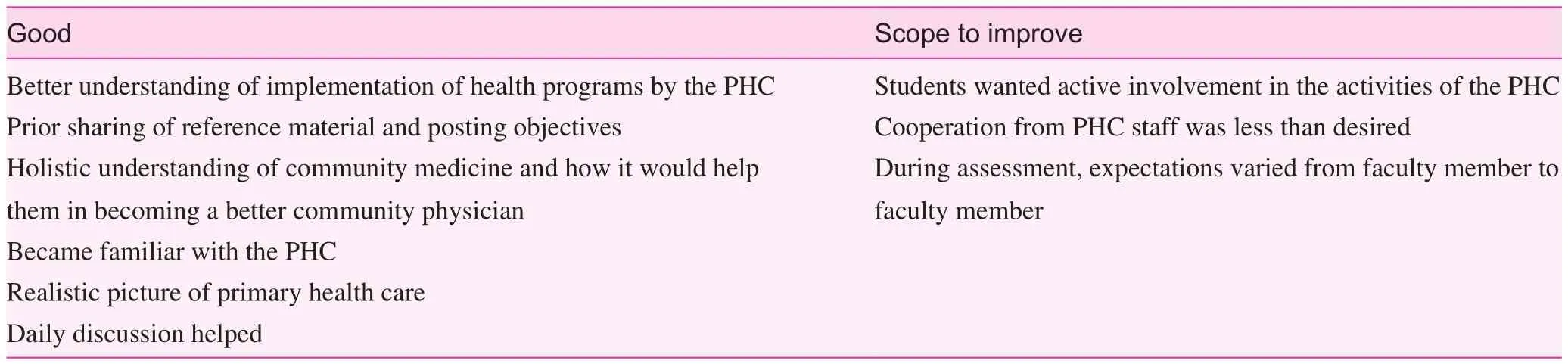

Anonymous written feedback was taken from these sixthsemester students. We asked them to classify their comments into two groups: points/themes perceived as ‘good’ by students, and points where there was scope for improvement,keeping in mind the changes in the community posting from their previous posting in the fourth semester. The findings are summarized in Table 2. The aim was Kirkpatrick level 1 (satisfaction) evaluation, keeping the revised community posting schedule in context.

Under points perceived as ‘good,’ students acknowledged that daily discussion helped them to understand the concepts better when compared with one-time discussion and assessment during their previous two community postings in the third and fourth semesters. Through the posting being conducted entirely in the PHC, they became familiar with the functioning of the PHC and with its staff. This gave them a realistic picture of primary health care of common ailments in resource-constrained settings. Students found the health management and epidemiological exercise to be informative.They also appreciated that relevant study materials/guidelines and learning objectives of the postings were e-mailed to them. Students mentioned that they understood the principles of community medicine better, and how active learning will aid their overall development as a community physician. They also understood the relevant health programs which were being implemented through the PHC. Students were able to understand the various factors affecting health at individual,family, and community levels.

Students stated that they would have appreciated more active participation by their being involved in the different functions of the PHC – namely, out patient department, special clinics( antenatal, immunization), domiciliary visits of health staff etc.A few difficulties were reported by the students. First, they found it difficult to identify houses that were allotted to them for family cases. Second, there was less than expected cooperation from families as well as PHC staff in this regard. Third, students mentioned that during the assessment of the clinical– psychosocial case review, expectation from each faculty member was different when it came to PHC-level management of a case.

Way forward

Our approach ensured that the community posting was totally community based. By the sharing of study materials with the students at the beginning of the posting through e-mail,students had the opportunity to prepare for the posting and were clear about what was expected of them. Students, by becoming sensitized to core disciplines of community medicine, got a holistic understanding of the subject, which was previously perceived to be associated only with departmental presentation/assessment and sporadic visits to a PHC.

Our community posting program was in a setting where training of students was the primary goal. During thiscommunity posting, the department was not involved in providing health services and conducting research at the PHC.The PHC, along with its staff, was not under administrative control of the community medicine department. This setup also does not encourage complete cooperation and involvement of the overburdened staff of the PHC. This reduces the motivation of students and they feel like outsiders or bystanders.

Table 2. Summary of students’ feedback regarding a revised community positing program at a primary health center (PHC) attached to a teaching hospital in Puducherry, India (2013)

The department is looking forward to getting complete administrative control of the PHC soon as a UHTC to provide health services and conduct need-based research in the UHTC. This will address all the points where there was scope for improvement according to the students; community (families) and health staff cooperation will not be an issue. Once community medicine faculty along with their team perform their primary role [6] and practice the four core disciplines in the UHTC, case management will be streamlined and students will appreciate the fact that faculty are practicing what they are teaching. Further, there will not be a need to have a faculty member in charge for every community posting as the faculty member in charge of the UHTC could manage the community postings.

Community medicine departments must refrain from merely ‘showing’ primary health care to undergraduate students; they should get actively involved in health care delivery. Provision of community-based health care services and/or research should be an integral part of community medicine practice as this helps in developing a rapport and getting accepted by the community [11]. It is the curative role that builds trust in the community. The same has not been addressed in similar communications where community posting was being assessed [12, 13]. We quote one of our students verbatim: “We would have benefitted more if we had our own PHC by now.”

In early 2014, the handover of the PHC to the Department of Community Medicine as a UHTC began in a phasewise manner. In the initial phase, a community medicine faculty member was involved in the routine functioning of the UHTC,with complete handover planned over 1 to 2 years. In early 2014, fourth-semester students had a clinical posting, where the points identified by students with scope for improvement were addressed.

Conclusion

It is important to introduce medical undergraduates to the core disciplines of community medicine early through community postings. Community postings should be conducted with the PHC/UHTC as a focal point. Departments of community medicine need to practice what they intend to teach in terms of students fulfilling their roles as community physicians and not just teach community medicine in classrooms. Assessment of students from the initiation (in the third semester) through completion (internship) of community postings has to be done in the future to understand the effectiveness of this framework of community postings better. A higher level of evaluation beyond Kirkpatrick level 1 needs to be conduced in the future.Feedback from others – namely, faculty, medical officers, and other PHC staff – also needs to be studied. The financial implications of the changes implemented in the community posting program are also an area of interest.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

1. Kark JD, Abramson JH. Sidney Kark’s contributions to epidemiology and community medicine. Int J Epidemiol 2003;32(5):882–4.

2. Kumar R. Development of community medicine sub-specialities.Indian J Community Med 2005;30(2):43.

3. Kumar R. Academic community medicine in 21st century: challenges and opportunities. Indian J Community Med 2009;34(1):1–2.

4. American Academy of Family Physicians. Family Medicine Specialty. [accessed 2015 Jun 14]. Available from: www.aafp.org/about/the-aafp/family-medicine-specialty.html.

5. Magzoub ME, Schmidt HG. A taxonomy of community-based medical education. Acad Med 2000;75(7):699–707.

6. Shewade HD, Jeyashree K, Chinnakali P. Reviving community medicine in India: the need to perform our primary role. Int J Med Public Health 2014;4(1):29–32.

7. Medical Council of India. Vision 2015. New Delhi, India; 2011.[accessed 2013 July 1]. Available from: www.mciindia.org/tools/announcement/MCI_booklet.pdf.

8. Rao S. Doctors by merit, not privilege. The Hindu. Chennai,India; 2013 Jun 26. [accessed 2013 July 1]. Available from: www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/doctors-by-merit-not-privilege/article4850500.ece.

9. Shewade HD, Jeyashree K, Tripathy J. Attracting doctors to rural health services of India. Natl J Med India 2012;25(6):374.

10. Kumar R. Medical education in India: an introspection. Indian J Public Adm 2014;60(1):146–54.

11. Nongkynrih B, Anand K, Kusuma YS, Rai SK, Misra P. Linking undergraduate medical education to primary health care. Indian J Public Health 2008;52(1):28–32.

12. Misra S, Baxi RK, Chavada P. Assessment of clinical postings in community medicine at a medical college in western India – a focus group discussion with teachers. National Journal of Community Medicine 2010;1(5):168–9.

13. Marahatta SB, Sinha NP, Dixit H, Shrestha IB, Pokharel PK.Comparative study of community medicine practice in MBBS curriculum of health institutions of Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J 2009;7(28):461–9.

Related lnformation

There are many articles focusing on family medicine training in developed countries, but few pay close attention to developing countries. In this article, the authors present their experience on training medical undergraduates in the core disciplines of community medicine through community postings in India, highlighting the importance of introducing medical undergraduates to the core disciplines of community medicine early through community postings, and noting that community postings should be conducted with a primary health center or an urban health and training center as the focal point. Although some aspects need further improvement, such as the lack of objective data, the article offers some valuable information on community posting, and can be a guide and reference for establishing training models or programs in developing countries.

More articles focusing on family medicine education and training in Family Medicine and Community Health are as follows.

· The challenges of cross-cultural research and teaching in family medicine – how can professional networks help?

www.ingentaconnect.com/content/cscript/fmch/2016/00000004/00000002/art00006

· Integrated care and training in family practice in the 21st century: Taiwan as an example

www.ingentaconnect.com/content/cscript/fmch/2016/00000004/00000001/art00010

· Turning cross-cultural medical education on its head: Learning about ourselves and developing Respectful Curiosity

www.ingentaconnect.com/content/cscript/fmch/2016/00000004/00000002/art00007

· The challenge of training for family medicine across different contexts: Insights from providing training in China

www.ingentaconnect.com/content/cscript/fmch/2016/00000004/00000002/art00009

· A resident’s perspective on why global health work should be incorporated into family medicine residency training

www.ingentaconnect.com/content/cscript/fmch/2016/00000004/00000001/art00008

· Implementation of a novel train-the-trainer program for pharmacists in China

www.ingentaconnect.com/content/cscript/fmch/2016/00000004/00000001/art00011

External Link

The Kirkpatrick Model

The Kirkpatrick Model is the worldwide standard for evaluating the effectiveness of training. It considers the value of any type of training, formal or informal, across four levels.

http://www.kirkpatrickpartners.com/OurPhilosophy/TheKirkpatrickModel/tabid/302/Default.aspx

Current Affiliation

aInternational Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease(The Union), South-East Asia Office, C-6, Qutub Institutional Area, New Delhi, India

bDepartment of Preventive and Social Medicine, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER),Puducherry, India

Hemant Deepak Shewade, MBBS,MD

International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union), South-East Asia Office,C-6, Qutub Institutional Area,New Delhi 110016, India

E-mail: hemantjipmer@gmail.com

9 September 2015;

Accepted 2 November 2015

Family Medicine and Community Health 2016;4(3):45-50

www.fmch-journal.org DOI 10.15212/FMCH.2015.0153

? 2016 Family Medicine and Community Health

Family Medicine and Community Health2016年3期

Family Medicine and Community Health2016年3期

- Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- Long-term care for aged ethnic minority people in Yunnan, China:Understanding the situation

- Maternal health and its affecting factors in Nepal

- The global reach of family medicine and community health

- ‘Face’ and psychological processes of laid-off workers in transitional China

- An innovation in child health: Globally reaching out to child health professionals

- The Malaysian health care system: Ecology, plans, and reforms