The Malaysian health care system: Ecology, plans, and reforms

Andrea Sebastian, Mohamed Ali Alzain,5, Collins Otieno Asweto, Gehendra Mahara, Xiuhua Guo, Manshu Song,Youxin Wang, Wei Wang,4

1. School of Public Health, Capital Medical University, Beijing,China

2. Beijing Municipal Key Laboratory of Clinical Epidemiology,Beijing, China

3. Beijing Municipal Key Laboratory of Environmental Toxicology, Beijing, China

4. School of Medical and Health Sciences, Edith Cowan University, Perth, WA, Australia

5. Community Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Dongola, Sudan

The Malaysian health care system: Ecology, plans, and reforms

Andrea Sebastian1,2, Mohamed Ali Alzain1,2,5, Collins Otieno Asweto1,3, Gehendra Mahara1,2, Xiuhua Guo1,2, Manshu Song1,2,Youxin Wang1,2, Wei Wang1,2,4

1. School of Public Health, Capital Medical University, Beijing,China

2. Beijing Municipal Key Laboratory of Clinical Epidemiology,Beijing, China

3. Beijing Municipal Key Laboratory of Environmental Toxicology, Beijing, China

4. School of Medical and Health Sciences, Edith Cowan University, Perth, WA, Australia

5. Community Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Dongola, Sudan

Malaysia is on its way to achieving developed nation status in the next 4 years. Currently,Malaysia is on track for three Millennium Development Goals (MDG1, MDG4, and MDG7). The maternal mortality rate, infant mortality rate, and mortality rate of children younger than 5 years improved from 25.6% (2012) to 6.6% (2013), and 7.7% (2012) per 100,000 live births, respectively whereas immunization coverage for infants increased to an average of 90%. As of 2013 the ratio of physicians to patients improved to 1:633 while the ratio of health facilities to the population was 1:10,272. The current government administration has proposed a reform in the form of the 10th Malaysian Plan coining the term “One Care for One Malaysia” as the newly improved and reorganized health care plan, where efficiency, effectiveness, and equity are the main focus. This review illustrates Malaysia’s transition from pre-independence to the current state, and its health and socioeconomic achievement as a country. It aims to contribute knowledge through identifying the plans and reforms by the Malaysian government while highlighting the challenges faced as a nation.

Health care; health care reform; One Care; Malaysia

Ecology

Geography and country profile

Malaysia is located immediately north of the Equator in Southeast Asia and is separated by the South China Sea as Peninsular Malaysia and East Malaysia/Malaysian Borneo (the states of Sabah and Sarawak) [1, 2]. Malaysia,a federal constitutional monarchy, comprises a 13-state federation and the federal territories of Kuala Lumpur (the capital city), Putrajaya (seat of the federal government and administrative hub), and Labuan [1, 2].

As of 2014 the estimated population was 30,337,911, with a density of 92/km2, approximately 80% of whom are concentrated in Peninsular Malaysia [3, 4]. Malaysia is a multiracial country of diverse ethnicities and culture; the country’s current demographics comprises Malay-Muslim Bumiputras and non-Muslim Bumiputras (67.9%), Chinese(24%), Indians (7.2%), and other ethnicities(0.9%) [5, 6]. With a GDP of 5.6% during the third quarter of 2014, Malaysia, a fairly young country, has had one of the best economic records in Asia since its independence in 1957 [3]. Malaysia is rich in natural resources, and these have traditionally fuelled the economy, but is ever expanding its field of science and technology, commerce, tourism,and medical tourism.

In 1999 the Malaysian health indicators revealed that it was virtually on par with developed nations and better than its neighbors within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) as stated in the World Heath Report [2, 7]. Fifteen years later, International Living, an American publication, rated Malaysia’s health care system as the third best among those of the 24 countries in its 2014 Global Retirement Index surpassing Spain, Ireland, New Zealand, Italy, and France, scoring an overall total of 95% after Panama and Ecuador, respectively [8]. It was pointed out that the expertise of Malaysian health care practitioners is “equal to or better than what it is in most Western countries” [8].

Malaysia’s standing on the world stage has been further elevated as Kuala Lumpur was ranked the fourth most popular city as a tourist destination for shopping as indicated by the CNN Travel 2013 Report and the Globe Shopper Index 2012 [6, 9, 10]. As this gives Malaysia the opportunity to highlight its health care services in concordance with its medical-tourism base, the government proposed 2014 as the Visit Malaysia Year and 2015 as the Year of Festivals to encourage and attract tourists thus expanding the tourism sector and its revenue [5].

In the 1950s before independence, conditions such as infectious diseases and malnutrition were prevalent [7, 11–13].However, since Malaysia’s independence (August 31, 1957),there has been an epidemiological transition to diseases that are associated with affluence and lifestyle [11–14]. As a consequence, the health care system has undergone a major reorganization, shifting it from an illness service to a wellness service [7, 11–13]. As research suggests, there is a strong association between quality primary health care services and improved health indicators. As such, the initial reorganization was concentrated predominantly on developing a nationwide primary health care network, which was further augmented by the Alma Ata Declaration in 1978 [2, 15].

Malaysia’s health care system

Malaysia has a dual health care system, and the three main providers of health care are public organizations, private organizations, and to a smaller extent, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) [2, 7, 12, 16]. However, in concordance with the Federal Constitution, the Ministry of Health (MOH)is the primary provider, financier, and regulator of health services; hence it is responsible for the population health and the implementation of health promotion [2, 7, 16]. This is achieved by the blanketing effect of all facets of care, such as prevention, promotion, therapy, and rehabilitation [2, 7, 16]. The hierarchical organization of the MOH is stratified into the federal,state, and district levels, which ensures efficiency through decentralization [2, 7, 16].

Under the umbrella of the MOH, 5 of 33 bodies complement the role of the MOH in upholding the health care system as a whole [2, 16, 17]. The provision of physical and sanitary health care education at government and privately owned schools, regulation and supervision of internationally recognized medical universities and teaching hospitals, the adherence to and maintenance of international protocols and standards in schools, universities, and hospitals, and the training of health personnel come under the purview of the Ministry of Education [2, 16, 17]. Responsibility for the safety and health of industrial and estate plantation workers as well as the estate hospitals falls under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Human Resources [2, 16, 17]. Under the aegis of the Ministry of Defense, health care services for its personnel and their dependents as well as the community at large within its territory are provided [2, 16, 17]. Native or aboriginal health and forest hospitals are the responsibility of the Ministry of Rural Development [2, 16, 17]. In addition, the Ministry of Housing and Local Government is responsible for the licensing and implementation of health legislation under its authority [2, 16, 17].

The private health sector, which encompasses private hospitals and clinics (private general practitioner practices), is the second major health care provider in the country [2]. With clinics mushrooming throughout the country, especially in the urban settlements around every housing area, it delivers closeto-home care, while also fulfilling the role of primary care providers, gatekeepers, and first-step referrals [2].

Traditional medicine that includes Malay, Chinese,Ayurvedic, and other herbal and complementary medication has also been incorporated in some private hospitals as a method of treatment [2]. The final tier of healthcare providers is the NGOs [2]. There are approximately 132 NGOs in Malaysia, and many of them complement the MOH in providing alternative health care and treatment [2]. Health care NGOs include Cancerlink Foundation, Hospis Malaysia,The Malaysian Liver Foundation, and The Malaysian AIDS Foundation, which work in tandem with other NGOs such as the Pink Triangle Foundation, Pelangi, Prihatin, and the Prostar Club – all of which help patients with HIV/AIDS [18–25].

Sociodemography and health indicators

Health indicators for the maternal mortality rate show that there was a massive decrease from 530 cases in 100,000 live births in 1950 to 25.6 cases in 100,000 live births in 2012 [12,26, 27] (Fig. 1). The infant mortality rate decreased from 75.5 per 1000 live births in 1957 to 6.6 per 1000 live births in 2013[12, 26–30] (Fig. 2). However, compared with the infant mortality rate in developed countries such as Singapore (2 per 1000 live births), the United Kingdom (4 per 1000 live births), the United States (6 per 1000 live births), Canada (5 per 1000 live births), and Australia (4 per 1000 live births), the infant mortality rate in Malaysia is still considered relatively high for a country aiming to become a developed nation by 2020 [31].

Childhood immunization coverage for infants as of 2013 was 98.56% for BCG, 96.92% for DPT-HIB, 96.87% for polio,96.32% for hepatitis B (third dose), and 94.33% for human papillomavirus for girls aged 13 years (third dose). The IMR for children aged 1 year to less than 2 years was 95.25%. The life expectancy at birth increased to 74.72 years in 2013 from 56.5 years in 1957 [27, 32].

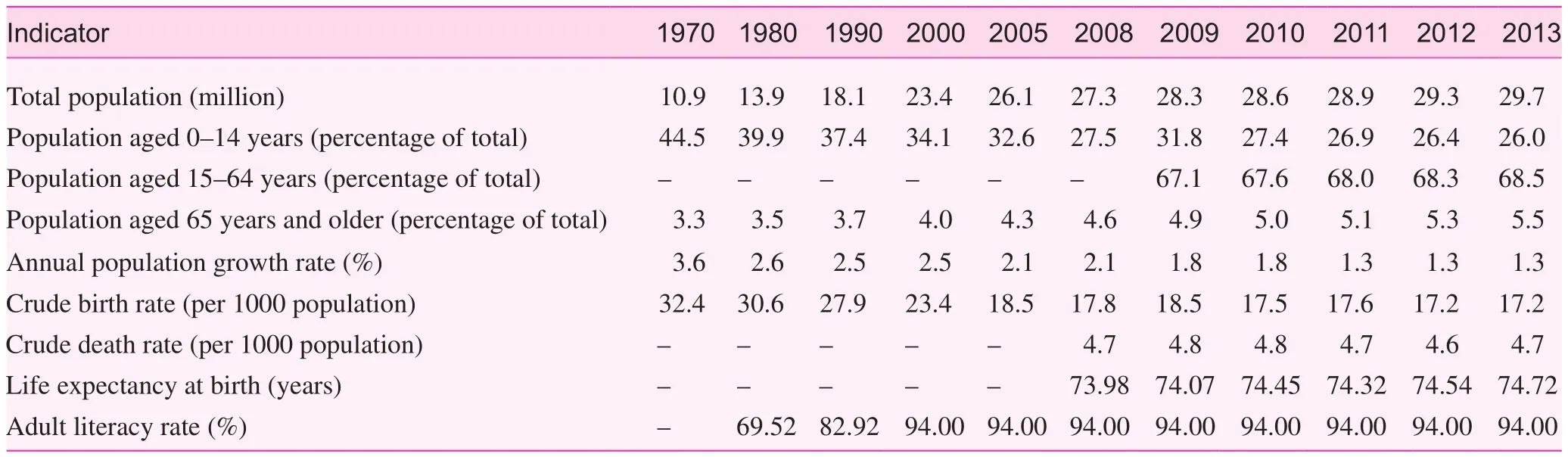

The annual population growth rate decreased from 3.6%in 1970 to 1.3% in 2013, with the proportion of the population older than 65 years increasing to 5.5% in 2013 from 3.3% in 1970, whereas the total dependency ratio decreased from 72.0% in 1985 to 46.4% in 2013 [12, 14]. The per capita income in 2013 was US$9754.46, with a GDP at constant 2005 prices of US$212.5 billion [4]. The unemployment rate was 2.7% in October 2014, and the literacy rate of individuals older than 15 years was 94% in 2013 [3] (Table 1).

Health care facilities and human resources

In 1999 the number of specialist doctors counted for 63.5%,and 82.8% for general practitioners [14]. In 2013, there were 46,916 physicians [20]. The ratio of clinicians (MOH, non-MOH, and private) to the population increased to 1:633 in 2013 from 1:1465 in 1999 [14, 27] however with the improved number of doctors there is still a need for more.

Fifty private hospitals in 1980 provided 1171 beds, increasing to 214 hospitals with 14,033 bed capacity in 2013 [2].Primary health care in Malaysia is delivered by private general practitioners as the first step of primary care for record keeping and referrals. In 1999 there were 1990 village clinics, 773 health clinics, and 120 government hospitals [14]. The ratio of village clinics to the population was 1:4787, and the ratio of health clinics to the population was 1:29,382 [14]. In 2013 the number of public hospitals under the MOH, special medical institutions (National Heart Institute, Institute of Pediatrics,and Institute of Respiratory Medicine), and non-MOH hospitals increased to 147, with 42,707 beds [4]. The number of health clinics increased to 919, the number of community clinics increased to 1831, the number of maternal and child health clinics increased to 106, and the number of 1Malaysia (One Malaysia) Clinics increased to 254 [4, 27]. The ratio of health facilities to the population improved to 1:10,272 [4]. The number of mobile health clinics increased to 212, with a Flying Doctor Service of 13 teams [27].

Reformed health plan

A formulated health plan is an integral part of national development [15]. The Ljubljana Charter states that the fundamental principles of health care must be driven by values, targeted at health, centered on people, focused on quality, based on sound financing, and oriented toward primary health care [2, 39].Reforms within a country should be transparent to the public and so should be continuously monitored and evaluated [15].

Table 1. Sociodemographic health indicators from 1970 to 2013

Health care reform in Malaysia began after independence and has been continuously restructured and improved, because a healthy population is an important asset to the country [15].The scope on which it was designed is based on three categories, specifically the Short Term Five Year Socioeconomic Development Plan, the Middle Term Outline Perspective Plan(OPP), and the Long Term Strategic Plan [2, 17]. All three plans converged with one intention: Vision 2020.

The Short Term Five Year Socioeconomic Development Plan, implemented as The First Malaya Plan, began in 1956 and Malaysia is currently in the 10th Malaysian Plan cycle(2011–2015) [17, 40, 41].

In the New Economic Policy (OPP1: 1971–1990), national unity was the primary framework [2, 17]. Restructuring of the community and eradication of poverty was the first course of action because there was a need to integrate a still young and newly formed nation into a system of harmonious and civilized culture [2, 17]. Following this 19-year plan was the National Development Policy (OPP2: 1991–2000) highlighting ‘growth with equity’ [2, 17]. This timeframe allowed the established governmental bodies to continue their efforts in alleviating poverty, eliminating economic imbalance, and introducing the private sector as the engine of growth within a national context[2, 17]. The final timeframe opened up the way to ‘national solidarity’ through its National Vision Policy (OPP3: 2001–2010)[2, 17]. This policy reiterates the eradication of poverty while continuing to foster unity within the nation, strengthening its human resource development, pursuing environmentally sustainable development and moving toward and sustaining high economic growth, and enhancing competitiveness through the development of a knowledge-based economy [2, 17].

The nation has developed from an agricultural-based economy into a modern industrialized economy and presently has an upper-middle-income status [5]. With the aim to become a fully ‘developed’ nation by 2020, Malaysia has to become a country with a high-income economy, and needs to have a lowest limit of yearly growth of 5.5% to achieve that status [17].

Vision 2020 states that “by the year 2020, Malaysia is to be a united nation with a confident Malaysian Society infused by strong moral and ethical values, living in a society that is democratic, liberal and tolerant, caring, economically just and equitable, progressive and prosperous, and in full possession of an economy that is competitive, dynamic, robust and resilient” [2, 17].

However, in 2010 Malaysia had a rising debt of RM362 billion and a rising deficit of RM47 billion, up from RM5 billion in 1998 [42], with debt having tripled in 2015 to RM740.7 billion [43]. If the government debt continues to increase at a rate of 12% per annum, the country will become bankrupt by 2019, with a debt exceeding RM1158 billion [42]. In a bid to save the country, measures have been taken to increase GDP and reduce expenditure [42]. The nation has been made aware that it is one of the most subsidized, and its subsidy bills in each category are RM42.4 billion for Public Welfare, RM23.5 billion for fuel and energy, RM4.8 billion for infrastructure,and RM3.4 billion for food, totalling RM74 billion, resulting in a subsidy of RM12, 900 per household [42]. Continuing at this rate would lead to bankruptcy, and thus a framework was developed for subsidy rationalization [42].

Therefore to progress toward achieving Vision 2020, a framework was created around the four pillars of change:the National Key Result Areas from the Government Transformation Programme; the 12 National Key Economic Areas of the Economic Transformation Programme; the New Economic Model; and the 10th Malaysian Plan [13]. The proposed model for the 10th Malaysian Plan includes the fivepoint National Mission Thrusts, which is a collective of six strategic directions leading to the six key result areas [41].

The National Mission Thrusts aims to move the economy up the value chain (thrust 1), to raise the capacity for knowledge and innovation and nurture ‘first class mentality’(thrust 2), to address persistent socioeconomic inequalities constructively and productively (thrust 3), to improve the standard and sustainability of quality of life (thrust 4), and to strengthen the institutional and implementation capacity(thrust 5) [17, 40, 41]. With focus on key resource area 2 of strategic direction 5, four strategies have been used to ensure access to quality health care and promotion of a healthy lifestyle [17, 40, 41]. To achieve an outcome where the key result areas reflect the health sector transformation toward a more efficient and effective health system in ensuring universal access to health care, health awareness, and healthy lifestyle, and where empowerment of individuals and the community is responsible for their health, measures have been applied to establish a comprehensive health care system and recreational infrastructure (strategy 1), encourage health awareness and healthy lifestyle activities (strategy 2),empower the community to plan or conduct individual wellness programs by taking responsibility for health (strategy 3), and transform the health sector to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of the delivery system (strategy 4) [17, 40,41]. The country’s aspirations for health care reform lead to restructuring and development within the delivery system,finance, and governance [17, 40]. Therefore the One Care concept was introduced to the nation. The One Care concept is a “restructured national health system that is responsive and provides choice of quality health care, ensuring universal coverage for health care needs of population based on solidarity and equity” [16].

One Care for One Malaysia budget proposition

The total health care budget for 2014 was set at RM22.1 billion [5]. Under the Operating and Development Expenditure,upcoming programs and projects which included construction and upgrading of hospitals and 30 rural clinics with the addition and establishment of 284 1Malaysia (One Malaysia)Clinics, accompanied by 2000 additional parking lots at the General Hospital Kuala Lumpur (the capital city hospital),were proposed [5]. In parallel, the National Cancer Institute likewise commenced operation [5]. Because of the continuous two-shift workload, the appointment of an additional 6800 nurses to improve the quality of nursing care was initiated[5]. Budget allocation similarly considered the purchasing of equipment and medicine to ensure appropriate treatment of patients, as well as the expansion of cardiothoracic services in hospitals within the major cities of different states [5].

To facilitate treatment of patients with end-stage kidney failure, the government anticipated providing free continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis kits to allow patients to be treated at home due to the difficulty patients have traveling to the hemodialysis center three times a week [5].Effective from 2013, the subsidy for sugar was abolished as statistics indicated that 2.6 million Malaysians younger than 30 years had diabetes [5].

As an addition to the human papillomavirus immunization services and mammogram screening, free breast prostheses and special bras for breast cancer patients have also been included in the budget [5]. The initiative will assist in offsetting the cost of purchasing the support material and will benefit more than 8000 breast cancer patients[5]. Furthermore, four special buses for the implementation of the Mobile Family Centre, which provides advisory services related to family matters, dietary requirements, and screening for chronic diseases, as well as testing for glucose and cholesterol, was initiated [5]. Supplementing the budget allocations, RM1.95 billion was provided for the financial support and upgrading of rural and Orang Asli (aborigines)living standards [5].

Malaysia: The Millennium Development Goals

Although health care improvements are highly welcomed, in terms of public health policies, they are inadequate, as health at a higher level is subjected to change by various circumstances [15]. The purpose of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) was to eliminate conditions that impede health.As of 2013 Malaysia had achieved one goal and was on track to achieve two others [44]. On the basis of the 2006 WHO reference population, Malaysia is on track to achieve MDG1 under the nutrition category [44]. Malaysia was also currently on track to achieve MDG4 according to the 2012 UN Interagency Group for Child Mortality Estimation [44]. Malaysia met the goal on water and sanitation under MDG7 as stated by the UNICEF/WHO Joint Monitoring Programme 2012 [44].The 2012 UNAIDS estimates for HIV/AIDS (MDG6) showed a low and concentrated epidemic [44].

To keep up with its MDG targets, the quality of education was to be improved further with the increase in the number of graduate teachers [13]. As a country trying to achieve a developed nation status, gender inequality must be addressed.Therefore the government took steps to ensure active participation of the female population within the workforce and that the female population contributes to decision making at all levels of both the public sector and the private sector [13]. Lastly,to ensure environmental sustainability in accordance with MDG7, conservation campaigns will be conducted to educate the people and with emphasis on the reduction of the production of greenhouse gases through the use of renewable energy and natural resources [13].

Current challenges and implications

The plans and reforms seem to be the right ingredients for a successful Malaysia, and on paper they seem to work well with reference to government statistics. However, the future of the economy looks to be unstable. With the external debt increasing from RM196 billion in the third quarter of 2013 to RM740.7 billion in 2015 [45], subsidy cuts [5], implementation of the 6%goods and services tax [46, 47] effected to prevent bankruptcy because of high government debt, and the increasing cost of living [48], the nation suffers as the country’s stability staggers. In the face of a political crisis that is affecting Malaysia, the central bank struggles as it tries to slow the decline of the ringgit, which slid from RM3.8 [49] per USD to RM4.29 per USD in 2015.The threshold level for poverty for a household is RM 1500 per month [50]. As cited by the World Bank, Malaysia nearly succeeded in eradicating poverty, where the proportion of households living below the national poverty threshold (US$8.5 per day in 2012) decreased from 50% to less than 1% in 2014 [51].With the economy being so precariously unstable, it remains to be seen if the government is committed to staying on track to achieve all the MDGs by 2020 – not just on paper but actively setting principals into action.

The current Malaysian health care system is just one of the many factions facing challenges within its structure[16]. One point of concern is the conflict-of-interest challenge between politicians and physicians [16, 52]. The number of medical representatives in parliament is very small compared with the number of politicians [52]. As very few politicians are medically literate and do not have experience or direct contact with patients, they do not really understand the current issues that are being faced by the medical community at large [52]. Therefore although it is easy to implement new regulations concerning health care, the two factions will not be able to come to an understanding that is mutually beneficial. This superfluous bureaucracy and protocol leads to corruption and unnecessary expenditure[52]. The consequence is that because of the lack of understanding and cooperation, development of the health care system is prolonged, and this leads to inefficiency on the part of physicians [52]. In the end, it is the public that suffers[52]. To curb such situations, implementation of the health care system should be reviewed and decisions should be left in the hands of those who are qualified to make them [49,52]. Medical practice and health issues should be considered separately without any political party being involved [52].

Another is the lack of integration between the public and private sectors [16, 52]. Rural health care in particular is still a cause for concern [14]. Although the rural clinics (1Malaysia Clinics) and hospitals are now better provided with equipment and facilities such as the Flying Doctor Service (eight helicopters), 1Malaysia Mobile Bus Clinics (eight teams), and 1Malaysia Mobile Boat Clinics (six teams), patients still prefer to seek medical care at tertiary hospitals instead of first seeking medical care from their primary care providers [14, 27]. One reason is that before the reform and the setting up of 1Malaysia Clinics, the primary care providers were almost always private practices that charged a fair amount for treatment. The consequence was that these practices could not perform their gatekeeping duties and thus the tertiary hospitals were flooded with patients requiring multiple levels of care [14]. Currently,the public sector is suffering because of the shortage of health care professionals (physicians and nurses) [49]. The public sector is still understaffed and housemen are working 120 hours a week, with a 40-hour shift with no rest [49]. This leads to suboptimal patient care. Health care professionals feel that they are being taken for granted and are not rewarded for their performance [16]. This gives rise to a brain drain within the public health sector as more and more professionals leave the country to seek better working conditions and better pay across the border, overseas, and even in the private sector within the country [2, 49, 52]. The consequence of this migration forces the MOH into a tight spot as practitioners are unwilling to be assigned to rural clinics/hospitals because services expected and taken for granted within the urban environment are hard to come by in the rural environment although access to them is being made much easier [14]. That said, however, there is still a huge gap, and so instead of continuously evolving in their learning of treatments and research, their education plateaus and thus stagnates. Professional and physical isolation creates a vacuum when what is required and needed is not provided. Substandard treatment because of dissatisfaction, lack of information and medical resources, and the inability to provide a proper diagnosis because of inadequate specialist care may lead to dangerous patient care [52]. Also, with the advent of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, it has been suggested that plants, animals, and medical procedures be subjected to patent protection and that patent law be approached in a very general manner [53]. This could mean greater patent litigation against physicians, surgeons, and medical professionals with regard to medical procedures especially [53]. Another resulting conundrum would be the delay in accessing generic drugs as patents could expire before the generic drug manufacturers produce and market them [53]. If this comes to pass, it would prove to be a major uphill battle for medical professionals, not just in Malaysia, but in many countries.

Third, is the limited coverage of treatments for catastrophic illnesses, which include hemodialysis, cancer therapy, and transplantations [16]. With the limited number of specialists on hand and full schedules daily, there is a long waiting list for certain treatments and medical care [14, 49, 52]. Although the private sector provides better facilities and quality treatment, it is mostly unaffordable for many citizens, preventing them from seeking medical care and treatment [52]. This then leads to greater expectations from members of the public as they depend on the government to provide an affordable and subsidized service with uniform accessibility [16].

Fourth is the cultural and religious challenge [52]. Although Malaysia is a multiracial country, it is a Muslim constitutionalized country. However, the practice of medicine is above culture and religion, but it is still somewhat influenced by the social components in Malaysia. For example, the teaching of sexually transmitted diseases and sex education are considered taboo [52, 54]. The overall outlook toward sexual intercourse is an abstinence and avoidance only approach [54]. As all the religions in Malaysia insist on sex after marriage, most people in Malaysia think that sex education is not required as they believe that sex education will lead to and increase premarital sexual activity among children and youths [54]. Parents leave the education of their children to the teachers and the education system which is imperfect. Thus the country suffers from ever-increasing numbers of teenage pregnancies, abortions,and abandoned babies [54]. In Malaysia, although the age at which one can legally marry is 18 years, according to Sharia law, Muslim girls younger than 16 years are allowed to marry with consent from the Syariah Court [55]. Statistics from the Malaysian Syariah Judiciary Department (JKSM) show that child marriages are still rampant, and this leads to risks to the physical health of the girls who marry and conceive too early[55]. The resultant effect is that many die of maternal health complications during delivery [55], increasing the maternal mortality rate.

Lastly, insufficient education on HIV/AIDS leads to misunderstanding and discrimination [52]. HIV/AIDS patients have to pay double the amount for medical treatment in certain hospitals in Malaysia [52]. Many health professionals tend to shy away from homosexuals, because alternative lifestyle choices are still not looked on kindly. Medical practice should be all encompassing, and physicians should remain neutral when treating patients, coinciding with the Hippocratic Oath that they swore [52]. Because sexually transmitted diseases are a very delicate matter, the treating physician should not exacerbate the problem with discrimination [52].

Conclusion

Malaysia faces a plethora of challenges, one of many being a multiracial country where religious freedom is practiced in an Islamic country. Implementations of policies have to take into account the many factions of races and how this affects the population at large. The focus on improving access to quality health care is lauded; however, as demographic and epidemiological transitions continue, demand for health care continues to rise while the government struggles with health care equity. That is not to say that the achievements so far are below par. Malaysia has risen beyond and above the status as a Southeast Asian country and is an example to many countries. However, there is still need for solutions to key challenges such as lack of access to water, sanitation, and proper waste management in rural areas,and the rapid rise in the cost of living. The increase in life expectancy has resulted in an increase in the incidence of noncommunicable diseases [56]. This is burden for a more efficient health care system with greater population coverage [56]. A worsening climate because of haze pollution leads to a rise in temperature,which then results in vector-borne diseases and exacerbated infectious diseases [56]. However, if the government continues to keep to its theme of “Strengthening Economic Resilience,Accelerating Transformation and Fulfilling Promises,” Malaysia will eventually meet all Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)and become a developed nation by 2020.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or from non-profit sectors.

1. Maps of the World. Map of Malaysia. 2014. [accessed 2014 Dec 30]. Available from: www.mapsofworld.com/malaysia/.

2. Ismail M, Yon R. Health care reform and changes: the Malaysian experience. Asia Pac J Public Health 2002;14(2):17–22.

3. Department of Statistics Malaysia. The source of Malaysia’s official statistics. Malaysia: Department of Statistics Malaysia; 2014.[accessed 2014 Dec 30]. Available from: www.statistics.gov.my/portal/index.php?lang=en.

4. Ministry of Health Malaysia. Health indicators 2013. Malaysia:Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2013.

5. Ministry of Finance Malaysia. Strengthening economic resilience, accelerating transformation and fulfilling promises. The Prime Minister/Minister of Finance’s 2014 Budget Speech. 2013.[accessed 2014 Oct 10]. Available from: www.treasury.gov.my/pdf/bajet/ucapan/ub14.pdf.

6. Department of Statistics. Population distribution and basic demographic characteristics 2010. Malaysia: Department of Statistics;2010. [accessed 2014 Dec 31]. Available from: www.statistics.gov.my/portal/index.php?option=com_contentamp;view=articleamp;i d=363amp;Itemid=149amp;lang=en#8.

7. Thomas S, Beh LS, Nordin R. Health care delivery in Malaysia: changes, challenges and champions. J Public Health Africa 2011;2(23):93–7.

8. International Living. The world’s best retirement haven 2014.International Living Global Annual Retirement Index 2014.2014. [accessed 2014 Sep 3]. Available from: http://internationalliving.com/2014/01/the-best-places-to-retire-2014/.

9. CNN Travel. World’s 12 best shopping cities. 2013. [accessed 2014 Dec 31]. Available from: http://edition.cnn.com/2013/11/18/travel/worlds-best-shopping-cities/.

10. Economist Intelligence Unit. The Globe Shopper Index – Asia Pacific. 2012. [accessed 2014 Dec 31]. Available from: www.globeshopperindex.com/en/Download/asian_paper.

11. Ministry of Health. Country health plan: 10th Malaysia Plan 2011–2015. Malaysia: Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2011.

12. Jaafar S, Noh KM, Muttalib KA, Othman NH, Healy J, Maskon K,et al. Malaysia health system review. Health Syst Transit 2013;3(1):1–103.

13. Economic Planning Unit Prime Minister’s Department Malaysia amp;United Nations Country Team Malaysia. Malaysia: United Nations Country Team; 2011. Malaysia, United Nations Country Team,Malaysia. 2010. [accessed 2014 Dec 8]. Available from: www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/MDG/english/MDG%20 Country%20Reports/Malaysia/Malaysia%20MDGs%20 report%20clean%202010.pdf.

14. Yusof K, Neoh KH, bin Hashim MA, Ibrahim I. Role of teleconsultation in moving the healthcare system forward. Asia Pac J Public Health 2002;14(1):29–34.

15. Raminashvili D, Bakhturidze G, Zarnadze I, Peikrishvili N,Bull T. Promoting health in Georgia. Glob Health Promot 2014;21(1):5–12.

16. Hamid MA. 2010. Report from the Deputy Director General of Health. 1Care for 1Malaysia: restructuring the Malaysian health system. 10th Malaysia Health Plan Conference, Malaysia.

17. Hamidy MA. 2010. The Malaysian health care system. Planning and Development Division, Ministry of Health. Malaysia.

18. Cancerlink Foundation. 2015. [accessed 2015 Jan 9]. Available from: www.cancerlinkfoundation.org/.

19. Hospis Malaysia. 2015. [accessed 2015 Jan 9]. Available from:www.hospismalaysia.org/.

20. Malaysian Liver Foundation. 2015. [accessed 2015 Jan 9].Available from: www.liver.org.my/.

21. Malaysian AIDS Foundation. 2015. [accessed 2015 Jan 9].Available from: http://www.mac.org.my/v3/.

22. Pelangi Foundation – Home For People Living With HIV / AIDS(PLWHA). 2015. [accessed 2015 Jan 9]. Available from: http://www.hati.my/children/pelangi-community-foundation/.

23. PROSTAR Club – Anti-AIDS Programme and Education Under The Healthy Programme Without AIDS for Youth. 2015.[accessed 2015 Jan 9]. Available from: http://www.hati.my/support-groups/prostar-club-anti-aids-programme-educationhealthy-programme-without-aids-youth/.

24. Pink Triangle Foundation – Community-based NGO Providing Information, Education and Care Services Relating to HIV/AIDS and Sexuality in Malaysia. 2015. [accessed 2015 Jan 9]. Available from: www.ptfmalaysia.org/.

25. Pertubuhan Masyarakat Prihatin. 2006. One stop crisis centre for single mothers and orphans living with HIV/AIDS.

26. Ministry of Health Malaysia. Health facts 2012. Malaysia:Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2012.

27. Ministry of Health Malaysia. Health facts 2014. Malaysia:Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2014.

28. Ministry of Health Malaysia. Health facts 2010. Malaysia:Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2010.

29. Ministry of Health Malaysia. Health facts 2013. Malaysia:Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2013.

30. World Bank. World development indicators – infant mortality rate data. 2014. [accessed 2014 Dec 30]. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/ indicator/SP.DYN.IMRT.IN.

31. World Health Organization. World health statistics 2014. Geneva:World Health Organization; 2014.

32. World Health Organization amp; UNICEF. Malaysia: WHO amp;UNICEF estimates of immunization coverage 2013 revision.2013. [accessed 2014 Jul 8]. Available from: www.childinfo.org/files/malaysia_rev_13_FINAL.pdf.

33. Ministry of Health Malaysia. Annual report 2010. Malaysia:Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2010.

34. Ministry of Health Malaysia. Health indicators 2010. Malaysia:Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2010.

35. Ministry of Health Malaysia. Annual report 2011. Malaysia:Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2011.

36. Ministry of Health Malaysia. Annual report 2012. Malaysia:Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2012.

37. Ministry of Health Malaysia. Health indicators 2012. Malaysia:Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2012.

38. Index Mundi. Malaysia – literacy rate. Index mundi – country facts. 2014. [accessed 2014 Dec 1]. Available from: www.indexmundi.com/facts/ malaysia/literacy-rate.

39. World Health Organization European Region. Ljubljana Charter On Reforming Health Care in Europe. Ljubljana: World Health Organization; 1996.

40. Ministry of Health. Strategic plan 2011 – 2015: 1Care for 1Malaysia. Planning and Development Division 2011. Malaysia:Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2011. [accessed 2014 Oct 10].Available from: www.moh.gov.my/images/gallery/Report/Plan_Strategik_KKM%202011-2015.pdf.

41. World Health Organization (WHO) Malaysia. Country cooperation strategy at a glance. Malaysia: World health Organization; 2013. [accessed 2015 Jan 8]. Available from: www.who.int/countryfocus/cooperation_strategy/ccsbrief_mys_en.pdf.

42. Jala I. The Performance Management and Delivery Unit(PEMANDU). Malaysian Subsidy 2010 report and Government Transformation Programme. Report of the Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department. 2010. [accessed 2014 Sep 23].Available from: www.slideshare.net/kzamandarus/malaysiansubsidy-2010-report.

43. Rahim R. Najib: Malaysia’s external debt trippled to RM740bil due to ‘new loan definitions’. The Star Online. 2015, March 11.[accessed 2015 Dec 20]. Available from: www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2015/03/11/najib-msian-debt-triple-definitions/.

44. UNICEF – Unite For Children. Malaysia: progress toward the Millennium Development Goals and other measures of the well-being of children and women. Statistics amp; Monitoring Section/Division of Policy and Strategy. 2013. [accessed 2014 Dec 27]. Available from: www.unicef.org/eapro/MDG_Profile_Malaysia_2013.pdf.

45. The Business Times Government and Economy. Malaysia reserves fall below US$100b as ringgit slumps. 2015, August 7.[accessed 2015 Dec 20]. Available from: www.businessties.com.sg/government-economy/malaysia-reserves-fall-below-us100bas-ringgit-slumps.

46. Ministry of Finance Malaysia. An Act to Apply a Sum from the Consolidated Fund for the Service of the Year 2015 and to Appropriate That Sum for the Service of That Year. The Prime Minister/Minister of Finance’s 2015 Budget Speech.2014. [accessed 2014 Oct 10]. Available from: www.pmo.gov.my/bajet2015/Budget2015.pdf.

47. Royal Malaysian Customs Department. Malaysia goods and services tax. Malaysia: Royal Malaysian Customs Department;2015. [accessed 2015 Dec 13]. Available from: http://gst.customs.gov.my/en/Pages/default.aspx.

48. Choong PK. Malaysians seen curbing spending as living costs surge economy. Bloomberg Business News. 2014. [accessed 2015 Dec 13]. Available from: www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-01-07/malaysians-seen-curbing-spending-asliving-costs-surge-economy.

49. Cheng T. Healthcare system needs ‘treatment’. The Star Online.2014, December 2. [accessed 2014 Dec 2]. Available from: www.thestar.com.my/Opinion/Letters/2014/12/02/Healthcare-systemneeds- treatment/.

50. The Edge Financial Daily. Selangor raises poverty threshold to RM1,500. 2014, November 25. [accessed 2015 Jul 2]. Available from: www.theedgemarkets.com/my/article/selangor-raises-povertythreshold-rm1500.

51. The World Bank. An overview of Malaysia: context, strategy, and results. 2015. [accessed 2014 Dec 30]. Available from: www.worldbank.org/en/country/malaysia/overview#1.

52. Hassan HI. A discourse on politics and current issues in healthcare system in Malaysia. Lecture Notes. Charles University Prague, First Faculty of Medicine. 2007. [accessed 2014 Dec 30]. Available from: http://web.lfhk.cuni.cz/patfyz/edu/CurrentHealthProblems2007-8/A%20Discourse%20 on%20Politics%20and%20Current%20Issues%20in.ppt.

53. Phelan A, Rimmer M. TPP draft reveals surgical strike on public health. East Asia Forum. 2013. [accessed 2015 Dec 9]. Available from: www.eastasiaforum.org/2013/12/02/tpp-draft-reveals-surgical-strike-on-public-health/.

54. Khalaf ZF, Wah YL, Merghati-Khoei E, Ghorbani B. Sexuality education in Malaysia: perceived issues and barriers by professionals. Asia Pac J Public Health 2014;26(4):358–66.

55. Azizan H. Child marriages on the rise. The Star Online. 2013, October 6. [accessed 2015 Dec 9]. Available from: www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2013/10/06/child-marriages-on-the-rise-1022-applications-approved-in-2012-compared-to-900-in-2011/.

56. Hashim J, Virasakdi C, Kai HP, Pocock N, Yap MT, Chhem RK,et al. Healthcare and healthcare systems in Southeast Asia.United Nations University-International Institute for Global Health. 2012. [accessed 2015 Dec 17]. Available from: http://iigh.unu.edu/ publications/articles/health-and-healthcaresystems-in- southeast-asia.html.

Related lnformation

There is a wide variety of health systems around the world. Malaysia, as a developing country, has a health care system that is better than some developed countries. Some of the challenges that Malaysia faces, such as the conflict-of-interest between politicians and physicians, the lack of integration between public and private sectors, the limited coverage of treatments for catastrophic Illnesses, cultural and religious issues, and insufficient education on HIV/AIDS leading to misunderstanding and discrimination also exist in many other countries. Nations should design and develop health care systems in accordance with their needs and resources.

Family Medicine and Community Health has published several articles in relation to health care system. These articles can give you important information on reform, model and other respects of health care system. You can find them below:

· Comprehensive reform of community health service in east, middle and west regions of China: from patients’ perspective

http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/cscript/fmch/2013/00000001/00000002/art00004

· Health professionals’ perspective on the impact of community health care reform in different regions of China

http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/cscript/fmch/2013/00000001/00000003/art00002

· Primary health care, a concept to be fully understood and implemented in current China’s health care reform

http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/cscript/fmch/2015/00000003/00000003/art00007

· The innovations in China’s primary health care reform: Development and characteristics of the community health services in Hangzhou

http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/cscript/fmch/2015/00000003/00000003/art00008

· Integration of community health workers into health systems in developing countries: Opportunities and challenges

http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/cscript/fmch/2016/00000004/00000001/art00006

· Exploration and practice of general practitioner responsibility system in an urban community of Shanghai

http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/cscript/fmch/2015/00000003/00000004/art00004

· Longitudinal study of a community hospital integrated model for diabetes management in the Beijing Jingsong community

http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/cscript/fmch/2014/00000002/00000001/art00004

External Link

Millennium Development Goals

http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/

S:Wei Wang, MD, PhD, FFPH

School of Medical and Health Sciences, Edith Cowan University, Perth, WA 6027, Australia

E-mail: wei.wang@ecu.edu.au

Youxin Wang, PhD

Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100069, China

E-mail: sdwangyouxin@163.com

22 December 2015;

Accepted 4 January 2016

Family Medicine and Community Health 2016;4(3):19-29

www.fmch-journal.org DOI 10.15212/FMCH.2016.0101

? 2016 Family Medicine and Community Health

Family Medicine and Community Health2016年3期

Family Medicine and Community Health2016年3期

- Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- Long-term care for aged ethnic minority people in Yunnan, China:Understanding the situation

- Maternal health and its affecting factors in Nepal

- The global reach of family medicine and community health

- ‘Face’ and psychological processes of laid-off workers in transitional China

- Training medical undergraduates in the core disciplines of community medicine through community postings – an experience from India

- An innovation in child health: Globally reaching out to child health professionals