Returning of cyclicity in infertile Corriedale Sheep with natural progesterone and GnRH based strategies

Lone F. A.*, Malik A. A., Khatun A., Islam R., Khan H. M, Shabir M.Division of Animal Reproduction, Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Faculty of Veterinary Sciences and Animal Husbandry, Shuhama, SKUAST-K, Shalimar Campus, 90 006, J & K, IndiaDivision of Animal Breeding and Genetics, Faculty of Veterinary Sciences and Animal Husbandry, Shuhama, SKUAST-K, Shalimar Campus, 90 006, J & K, IndiaDivision of Livestock Production Management, Faculty of Veterinary Sciences and Animal Husbandry, Shuhama, SKUAST-K, Shalimar Campus, 90 006, J & K, India

ABSTRACT

Objective:To evaluate the return of ovarian cyclicity with four hormone based protocols during nonbreeding season in infertile Corriedale sheep. Methods:The return to ovarian cyclicity was considered in terms of percent estrous response rate (ERR). The time of exhibition of estrus after either sponge removal or last PGF2-αinjection, was considered as time to onset of estrus. Infertile Corriedale ewes were randomly selected and distributed into four groups corresponding to four hormonal protocols such as PsE (intravaginal progesterone sponges for 12 days and eCG (equine chorionic gonadotropin) at the time of sponge removal; n=6), GP (GnRH on day 0 and PGF2-αon day 5; n=7), GPG (GnRH on day 0, PGF2-αon day 5 and second injection of GnRH on day 7; n=7) and PsPG (Intravaginal progesterone sponges for 12 days, PGF2-α and gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) respectively, at 24 hour before and after sponge removal; n=8). Results:PsPG protocol produced significantly (P<0.05) higher ERR (87.5%) in ewes as compared to GPG (28.57%) but non-significantly (P>0.05) higher than GP (85.71%) and PsE (66%). Estrus was compact and more synchronized in PsPG group because 75 % of ewes exhibited estrus during the first 48 hours. The collective incidence of estrus (78.94 %) was also maximum during the first 48 hours. Conclusion:PsPG estrus induction strategy has a potential to replace eCG based protocols for returning of ovarian cyclicity in infertile Corriedale sheep.

ARTICLE INFO

Article history:

Received 23 June 2015

Received in revised form 8 November 2015

Accepted 18 November 2015

Available online 1 January 2016

?

Returning of cyclicity in infertile Corriedale Sheep with natural progesterone and GnRH based strategies

Lone F. A.1*, Malik A. A.1, Khatun A.1, Islam R.1, Khan H. M3, Shabir M.2

1Division of Animal Reproduction, Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Faculty of Veterinary Sciences and Animal Husbandry, Shuhama, SKUAST-K, Shalimar Campus, 190 006, J & K, India

2Division of Animal Breeding and Genetics, Faculty of Veterinary Sciences and Animal Husbandry, Shuhama, SKUAST-K, Shalimar Campus, 190 006, J & K, India

3Division of Livestock Production Management, Faculty of Veterinary Sciences and Animal Husbandry, Shuhama, SKUAST-K, Shalimar Campus, 190 006, J & K, India

ABSTRACT

Objective:To evaluate the return of ovarian cyclicity with four hormone based protocols during nonbreeding season in infertile Corriedale sheep. Methods:The return to ovarian cyclicity was considered in terms of percent estrous response rate (ERR). The time of exhibition of estrus after either sponge removal or last PGF2-αinjection, was considered as time to onset of estrus. Infertile Corriedale ewes were randomly selected and distributed into four groups corresponding to four hormonal protocols such as PsE (intravaginal progesterone sponges for 12 days and eCG (equine chorionic gonadotropin) at the time of sponge removal; n=6), GP (GnRH on day 0 and PGF2-αon day 5; n=7), GPG (GnRH on day 0, PGF2-αon day 5 and second injection of GnRH on day 7; n=7) and PsPG (Intravaginal progesterone sponges for 12 days, PGF2-α and gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) respectively, at 24 hour before and after sponge removal; n=8). Results:PsPG protocol produced significantly (P<0.05) higher ERR (87.5%) in ewes as compared to GPG (28.57%) but non-significantly (P>0.05) higher than GP (85.71%) and PsE (66%). Estrus was compact and more synchronized in PsPG group because 75 % of ewes exhibited estrus during the first 48 hours. The collective incidence of estrus (78.94 %) was also maximum during the first 48 hours. Conclusion:PsPG estrus induction strategy has a potential to replace eCG based protocols for returning of ovarian cyclicity in infertile Corriedale sheep.

ARTICLE INFO

Article history:

Received 23 June 2015

Received in revised form 8 November 2015

Accepted 18 November 2015

Available online 1 January 2016

Keywords:

Cyclicity

Estrus response rate

Infertile ewes

GnRH

Progesterone

Tel:91-0194-2262208 (landline official); 91-9622552335(mobile personal)

E-mail:dr.farooz462@gmail.com

1. Introduction

In temperate climates with mid or high latitudes, as in some northern parts of India, Sheep is a seasonal breeder[1], resume their ovarian cyclicity only after a long period of ovarian quiescence during spring and summer. The fertile reproductive activity is exhibited during the autumn, which actually corresponds to the increased concentration of melatonin in the blood. During this season the length of light period becomes short and the dark period goes long. Therefore there is a transition in the photoperiod from summer to autumn[1]. It is this transition in the amount of light between different seasons that mainly controls the reproductive seasonality in sheep. There is an ample evidence that the ovarian follicular growth continues to occur during the seasonal ovarian quiescence revealed through ultrasonography[2], but the follicles do not ovulate mainly because of occurrence of less number of LH pulses (one LH pulse every 8-12 h as against one pulse every 20 minutes during preovulatory surge[3, 4] that are required for ovulation and with the result progesterone levels in blood become negligible [4]. However such follicles are active, synthesize and secrete estrogen, which makes them good candidates to the stimulation with exogenous gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)[5] and thus ovulation can occur. This provides an opportunity to manipulate the ewe reproductive physiology to resume ovarian cyclicity for increased lamb productivity.

The ovarian activity in animals has been stimulated with varioushormones like progesterone, prostaglandin (PGF), equine chorionic gonadotropin (eCG) and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH[6-8]. The controlled progesterone releasing devices like sponges are very effective for estrus induction during non-breeding season in small ruminants[9, 10] impregnated with either natural progesterone[11] or fluorogestone acetate or medroxyprogesterone acetate[8,12,13]. The use of intravaginal sponges in combination with either eCG has boosted estrous response rate as gonadotropins stimulate ovarian follicular growth of cyclic as well as acyclic females[14- 16], promoting higher levels of estrogen resulting in earlier and compact estrous response[8]. Prostaglandins cannot be used alone during non-breeding season as the animals are acyclic and do not posses corpus luteum on their ovaries. However, when used in combination with progesterone and GnRH injection prove to be efficient in controlling the life span of an active corpus luteum. A single injection of Prostaglandin 24 hour before norgestomet implant removal and GnRH 24 hour after implant removal has been used to induce estrus in Baladi goats[17]. Exogenous GnRH stimulates release of both FSH and LH, with former stimulates follicular growth and latter induces ovulation of dominant follicle.

There are two categories of ewes which can be utilized for ovarian manipulation during the period of acyclicity. The first category includes the normal ewes which will conceive during the breeding season but become acyclic after lambing in late winter or early spring and the second includes the ewes that fail to conceive during the previous breeding season are considered as infertile. The percentage of dry ewes (infertile) has been reported to be 23.62% [18] and if such ewes are utilized for ovarian stimulation during the following non-breeding season can substantially boost the economy of a sheep farm. With this trial was carried out to record the effectiveness of various hormonal protocols in inducing estrus in infertile ewes during non-breeding season. It is worth to mention here that the non-breeding season besides infertile condition of ewes was also a limiting factor for returning of cyclicity.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and experimental design

The study was carried out at Mountain Research Centre for Sheep and Goat, Faculty of Veterinary Sciences and Animal Husbandry, Shuhama, located at the foot hills of greater Himalayan mountainous region of Kashmir at the outskirt of Srinagar city, which is in latitude 34°5′ North and longitude 74°48′ East and lies above the centre of the Kashmir valley at an altitude of 1585 m above mean sea level. A total of 28 infertile (acyclic) sexually mature Corriedale ewes (2-5 years of age) were selected and randomly distributed among four treatment groups. The body condition score and mean body weight of the animals were respectively 3 and (32.50 ±5.00 kg. As the ewes did not conceive during the previous breeding season and were considered as infertile. However, on clinico-gynaecological examination, the ewes were found healthy and routine deworming was done before the trial. The trial was conducted during April to May, which corresponds to non-breeding season for this breed under temperate climate and the ewes were grazed on lush green pastures from 9:00 am to 3:00 pm. Water and salt lick was provided at ad libitum. The ewes were not allowed to come in contact with the rams during the entire study. The four treatment groups are as under:

1)Group *PsE (n=6) - on day 0, the ewes in this group received intravaginal progesterone sponges (CSWRI, India) for a period of 12 days followed by an intramuscular injection of 400 IU of eCG (Folligon, Intervet India Pvt. Ltd.) at the time of sponge removal.

2)Group *GP (n=7) - on day 0, ewes were injected with 5 μg of Buserelin acetate, a GnRH analogue (Receptal, Intervet India Pvt. Ltd.) followed by an intramuscular injection on day 5 with 263 μg of Cloprostenol, a PGF2 analogue (Cyclix, Intervet India Pvt. Ltd.).

3)Group GPG (n=7) - on day 0, ewes were injected with 5 μg of Buserelin acetate followed by an intramuscular injection on day 5 with 263 μg of Cloprostenol and finally second injection of 5 μg of Buserelin acetate on day 7.

4)Group PsPG (n=8)- on day 0, the ewes in this group received intravaginal progesterone sponges (CSWRI, India) for a period of 12 days, followed by an intramuscular injection of 263 μg of Cloprostenol at 24 hour before and 5 μg of Buserelin acetate at 24 hour after sponge removal.

*Ps is abbreviation of Progesterone sponges, G is Gonadotropin, P is Prostaglandin, and E is ecG.

2.2. Parameters recorded

The parameters that were recorded include estrous response rate and time to onset of estrus. After the sponge removal or PGF2 injection, two healthy normal aproned rams with colored mark on the brisket region were kept with treated ewes from 5:00 pm to 9:00 am for a period of five days. The estrus was detected on the basis of tupping mark on rump, hyperactivity of the ewes and edema of vulva. The estrus detection was done twice daily i.e. morning and evening. The ewes with color mark on croup region and vulvar edema in the morning time were considered to have exhibited estrus from midnight and those who had color mark on the croup region in the evening time were considered to have exhibited estrus from mid-day [8]. The calculations were done as:

Estrous response rate= [no. of ewes exhibited estrus/ total no. of ewes treated]×100

Time to onset of estrus= time elapsed from the sponge removal or PGF2 injection to occurrence of estrus

2.3. Statistical analysis

The data obtained in respect of estrous response rate (ERR %) under different hormonal treatments was analyzed with Z test [19]. P value≤0.05 was considered as significant.

3. Results

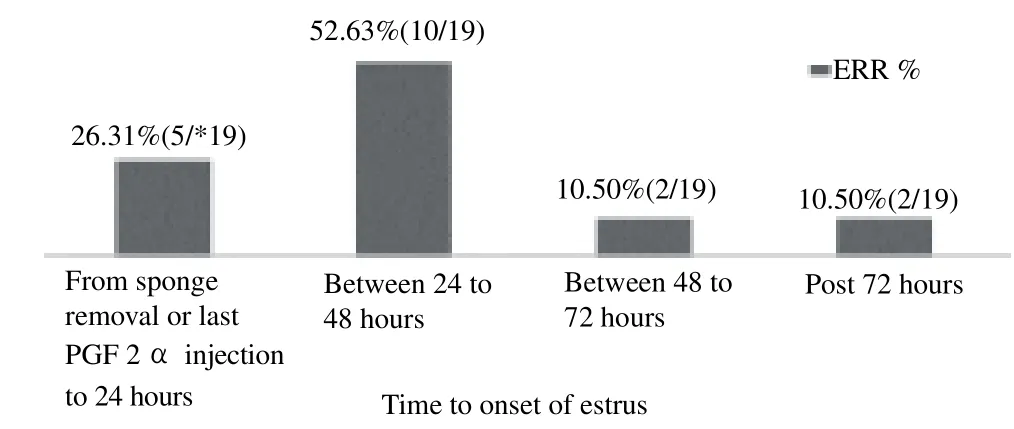

The distribution of the estrous response rate (ERR %) and timeto onset of estrus is set out in Table 1. The highest estrous response rate (87.50%) was recorded in group PsPG followed by GP and PsE protocols. This indicates that maximum ewes returned to ovarian activity in the PsPG (87.50%) and GP (85.71%) groups, which was significantly (P<0.05) higher than GPG (28.57%) and nonsignificantly higher than PsE (66.66%) groups (P>0.05). However, onset of estrus was more compact and synchronized in PsPG and PsE group as around 70% of ewes exhibited estrus up to 48 hours after sponge removal or last PGF2 injection. The estrus detected in GP group was more scattered and less synchronized. The most popular estrous induction protocol in cow (OVSYNCH) i.e., GPG produced estrus in only 28% of ewes. The ewes in this group showed estrus symptoms up to 48 hours only and no ewe was spotted in estrus after 48 hours. Irrespective of the treatment strategy, 78.14% ewes exhibited estrus during the first 48 hours after sponge removal or last PGF2 injection. The highest occurrence of estrous (52.63%) was between 24 to 48 hours (Figure 1). Only 10.5% of animals were spotted in estrus post 72 hours.

Figure 1. Cumulative response of ewes in terms of estrus with respect to time of initiation of treatment to exhibition. *Total number of ewes found in estrus = 19

Table 1 Estrous response rate and time to onset of estrus following different hormonal treatments during non-breeding season in ewes (%).

4. Discussion

Hormonal treatment to stimulate ovarian activity or to resume ovarian quiescence is a good strategy to ameliorate infertility condition in Corriedale ewes. The aim of this study was to resume cyclicity in ewes that did not conceive in previous breeding season. The ewes in group PsPG exhibited highest Estrous response rate (87.5%) as compared to other groups. These findings corroborate with Medan et al.[17], who obtained highly compact and synchronized estrous response rate (85%) in Egyptian Baladi goats during non-breeding season (3 mg norgestomet for 11 days + 150 μg of Cloprostenol at 24 hours before implant removal + 10.5 μg buserelin acetate 24 hours after implant removal). The higher estrous expression in PsPG group may be because of complete removal of endogenous progesterone source (CL) by the prostaglandin injection, culminating in strong progesterone withdrawal effect, which together with GnRH injection may have resulted in extensive follicular growth on the ovaries promoting higher levels of estrogen in blood. To our knowledge, PsPG protocol has never been tried in sheep and appears to be a better substitute for eCG based protocol in sheep because ecG may affect reproductive activity on subsequent use[17] through an immunological response against it (large glycoprotein and long half-life period). The second highest estrous response rate was recorded in GP group (85.71%) but the estrus was not compact. This is not in line with the study of Martemucci and D’Alessandro [8], who recorded only 47.7% estrous response rate with GP protocol. The reasons for higher estrous response rate in our study could be the difference in dose of Prostaglandin (263 μg), two different breeds, and climatic condition. The higher dose of prostaglandin ensures complete luteolysis which results in strong follicular wave emergence and more estrous expression. The estrus recorded in PsE (66.6%) group was comparable to the PsPG and GP protocol (P>0.05). In contrary to this, other workers[13]recorded an estrous response rate of 88.9% with MAP (60 mg) and PMSG (500 IU) and even higher estrous response rate (100%) was reported by Hashemi, et al[20] with MAP (60 mg) and PMSG (500 IU) and 93.3% by Martemucci and D’Alessandro[8], with FGA and ecG. The lower estrous response rate recorded in this study may be attributed to the infertility condition of ewes during the previous breeding season, breed and the dose of eCG (400IU). The most important finding of this study was that in GPG group, ewes only exhibited estrus (28%) before second GnRH injection. This is in accordance with Martemucci and D’Alessandro[8], who also obtained less estrous response rate (33.3%) with GPG protocol in Awassi ewes. This can be attributed to the fact that the dominant follicle formed after prostaglandin injection undergoes ovulation due to LH surge stimulated by the second GnRH injection. Thus the effect of estrogen gets abolished and the external exhibition of behavioral estrous ceases. It can be proposed that less estrous response rate in GPG protocol may result in less conception rate in natural mating because the portion of ewes that would have developed dominant follicle will not allow rams to mount after second GnRH injection because effect of estrogen vanishes due to ovulation of dominant follicle by the second GnRH injection. However, timed artificial insemination atsecond GnRH injection is the only choice to get maximum fertility in ewes stimulated with GPG. The time to onset of estrus was shorter i.e. maximum ewes exhibited estrus up to 48 hours in PsPG (75%) than in short term GnRH based protocols. This is in close agreement with the findings of other authors[8, 13, 21, 22]. The reason for compact and more synchronized estrous in PsPG group is attributed to the complete luteolysis of corpus luteum by prostaglandin given before the sponge removal and increased follicular activity with the GnRH injection given 24 hours after sponge removal. Collectively, more number of ewes (78.94 %) exhibited estrus during first 48 hours and only 10.5 % ewes displayed estrus post 72 hours after sponge removal or last PGF2 injection. The authors have not come across a single published report on returning of cyclicity in infertile ewes with hormones. In every published report, the experimental animals were cyclic during proceeding breeding season. Therefore this is the first report on returning of cyclicity in infertile ewes during nonbreeding season.

The authors concluded that PsPG protocol is a better substitute for estrus induction in infertile sheep for ameliorating infertility, but the fertility needs to be evaluated. Short-term GP protocol has also been proved effective in inducing cyclicity and GPG which is quite popular in bovines has limited applicability in sheep because natural mating is still practiced in this species and may find its place in timed artificial insemination where estrus detection is not required. However, further research in this area is required to evaluate the fertility of infertile ewes stimulated with PsPG, GP or GPG.

Declare of interest statement

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the staff of the division of Animal Reproduction, Gynecology and Obstetrics and MRCSG (Mountain research centre for Sheep and Goat), FVSc & AH Shuhama for their assistance during the entire trial.

References

[1] Gómez-Brunet A, Santiago-Moreno J, Toledano-Diaz A, López-Sebastián A. Reproductive seasonality and its control in Spanish sheep and goats. Trop Subtrop Agro Ecosyst 2012; 15(1):S47-S70.

[2] Souza CJH, Campbell BK, Baird DT. Follicular dynamics and ovarian steroid secretion in sheep during the follicular and early luteal phases of the estrous cycle. Biol Reprod 1997; 56:483-488.

[3] Bartlewski PM, Beard AP, Cook SJ, Rawlings NC. Ovarian follicular dynamics during anoestrous in ewes. J Reprod Fertil 1998; 113:275-285.

[4] I’Anson H, Legan SJ. Changes in LH pulse frequency and serum progesterone concentrations during the transition to breeding season in ewes. J Reprod Fertil 1988; 82:341-351.

[5] Southee JA, Hunter MG, Haresign W. Function of abnormal corpora lutea in vitro after GnRH-induced ovulation in the anestrous ewe. J Reprod Fertil 1988; 84:131-137.

[6] Keisler DH, Buckrell BC. Breeding strategies. In:Youngquist RS. (ed.) Current therapy in large animal theriogenology. Philadelphia:WB Saunders & Co; 1997, p. 603-611.

[7] Wildeus S. Current concepts in synchronization of estrous:Sheep and goats. J Anim Sci 2000; 77:1-14.

[8] Martemucci G, D’Alessandro AG. Estrous and fertility responses of dairy ewes synchronized with combined short term GnRH, PGF2 and estradiol benzoate treatments. Small Ruminant Res 2010; 93:41 - 47.

[9] Santos GMG, Silva-Santos KC, Melo-Sterza FA, Mizubuti IY, Moreira FB, Seneda MM. Reproductive performance of ewes treated with an estrous induction/synchronization protocol during the spring season. Anim Reprod 2011; 8(1/2):3-8.

[10] Abecia JA, Forcada F, González-Bulnes A. Hormonal control of reproduction in small ruminants. Anim Reprod Sci 2012; 130:173-179.

[11] Das GK, Naqvi SMK, Gulyani R, Pareek SR, Mittal JP. Effect of two doses of progesterone on estrous response and fertility in acycling crossbred Bharat Merino ewes in a semi- arid tropical environment. Small Ruminant Res 2000; 37:159-163.

[12] Ungerfeld R, Rubianes E. Short term primings with different progestogen intravaginal devices (MAP, FGA, and CIDR) for eCG-estrous induction in anestrous ewes. Small Ruminant Res 2002; 46:63-66.

[13] Dogan I, Nur Z. Different estrous induction methods during the nonbreeding season in Kivircik ewes. Vet Med-Czech 2006; 51:133-138.

[14] Cline MA, Ralston JN, Seals RC, Lewis GS. Intervals from norgestomet withdrawal and injection of equine chorionic gonadotropin or P.G. 600 to estrous and ovulation in ewes. J Anim Sci 2001; 79:589-594.

[15] Maurel MC, Roy F, Herve V, Bertin J, Vaiman D, Cribiu E, et al. Reponse immunitaire a la eCG uti- lisee dans le traitement de I’induction d’ovulation chez la chevre et la brebis. Gynecologie Obstetrique & Fer 2003; 31:766-769.

[16] Quintero-Elisea JA, Macías-Cruz U, Alvarez-Valenzuela FD, Correa-Calderón A, González-Reyna A, Lucero-Maga?a FA, et al. The effects of time and dose of pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG) on reproductive efficiency in hair sheep ewes. Trop Anim Health Prod 2011; 43:1567-1573.

[17] Medan M, Shalaby AH, Sharawy S, Watanabe G, Taya K. Induction of estrous during the non-breeding season in Egyptian Baladi Goats. J Vet Med Sci 2002; 64(1):83-85.

[18] Islam R, Nadroo GA, Sarkar TK, Bhat AS. Reproductive disorders of Corriedale ewes in an organized farm. Indian J Anim Reprod 2006; 27(11):37-41.

[19] Snedecor GW, Cochran WG. Statistical methods. 8th ed. Ames:Iowa State University Press; 1989.

[20] Hashemi M, Safdarian M, Kafi M. Estrous response to synchronization of estrous using different progesterone treatments outside the natural breeding season in ewes. Small Ruminant Res 2006:65:279-283.

[21] Zeleke M, Greyling JPC, Schwalbach LMJ, Muller T, Erasmus JA. Effect of progestagen and PMSG on estrous synchronization and fertility in Dorper ewes during the transition period. Small Ruminant Res 2005; 56:

47-53.

[22] Gardón JC, Escribano B, Astiz S, Ruiz S. Synchronization protocols in Spanish Merino sheep:reduction in time to estrous by the addition of ecG to a progesterone-based estrous Synchronization protocol. Ann Anim Sci 2015;

15(2):409-418.

doi:Document heading 10.1016/j.apjr.2015.12.012

*Corresponding author:Lone F. A., Division of Animal Reproduction, Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Faculty of Veterinary Sciences and Animal Husbandry, Shuhama, SKUAST-K, Shalimar Campus, 190 006, J & K, India.

Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction2016年1期

Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction2016年1期

- Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction的其它文章

- Diagnostic and decision-making difficulties:Placenta accreta at nine weeks’gestation

- Male masturbation device for the treatment of premature ejaculation

- Risk factors and adverse perinatal outcomes associated with low birth weight in Northern Tanzania:A registry-based retrospective cohort study

- Analysis of the androgen receptor CAG repeats length in Iranian patients with idiopathic non-obstructive azoospermia

- Effect of cooling to different sub-zero temperatures on boar sperm cryosurvival

- Milk supplements in a glycerol free trehalose freezing extender enhanced cryosurvival of boar spermatozoa