A revised Mississippian lithostratigraphy of County Galway (western Ireland) with an analysis of carbonate lithofacies, biostratigraphy, depositional environments and palaeogeographic reconstructions utilising new borehole data

Markus Pracht, Ian D. Somerville

1. Geological Survey of Ireland, Beggars Bush, Dublin 4, Ireland*

2. UCD School of Geological Sciences, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland

Abstract An integrated study of borehole data and outcrop of Mississippian (late Tournaisian to late Viséan) rocks in Co. (County) Galway, western Ireland has enabled a more detailed geological map and lithostratigraphy to be constructed for the region. Several carbonate formations have been distinguished by microfacies analysis and their precise ages established by micropalaeontological investigations using foraminifers and calcareous algae.In addition, palaeogeographic maps have been constructed for the late Tournaisian, and early to late Viséan intervals in the region. The oldest marine Mississippian (late Tournaisian)deposits are recorded in the south of the study region from the Loughrea/Tynagh area and further south in the Gort Borehole; they belong to the Limerick Province. They comprise the Lower Limestone Shale Group succeeded by the Ballysteen Group, Waulsortian Limestone and Kilbryan Limestone Formations. These rocks were deposited in increasing water depth associated with a transgression that moved northwards across Co. Galway. In the northwest and north of the region, marginal marine and non-marine Tournaisian rocks are developed,with a shoreline located NW of Galway City (Galway High). The central region of Co. Galway has a standard Viséan marine succession that can be directly correlated with the Carrick-on-Shannon succession in counties Leitrim and Roscommon to the northeast and east as far as the River Shannon. It is dominated by shallow-water limestones (Oakport, Ballymore and Croghan Limestone Formations) that formed the Galway-Roscommon Shelf. This facies is laterally equivalent to the Tubber Formation to the south which developed on the Clare-Galway Shelf. In the southeast, basinal facies of the Lucan Formation accumulated in the Athenry Basin throughout much of the Viséan. This basin formed during a phase of extensional tectonics in the early Viséan and was probably connected to the Tynagh Basin to the east. In the late Viséan, shallow-water limestones of the Burren Formation extend across much of the southern part of the region. They are characterized by the presence of rich concentrations of large brachiopod shells and colonial coral horizons which developed in predominantly high-energy conditions. These limestones also exhibit palaeokarstic surfaces and palaeosols which formed during regressive conditions of glacio-eustatically controlled cyclicity. Locally, slightly deeper water, lower energy conditions developed on the shelf with the formation of rare bryozoan-rich mud-mounds. Deep-water basinal facies were maintained in the central and southeastern parts of the region between the two shelves with the persistence of the Lucan Formation. Active syn-sedimentary faulting influenced deposition in the Viséan and interfingering of basinal sediments with slumps and shallow-water shelf carbonates are recognized.

Key words Carboniferous, Mississippian, western Ireland, carbonate microfacies,biostratigraphy, foraminifers, shelf and basin environments, palaeogeography

1 Introduction and geological setting

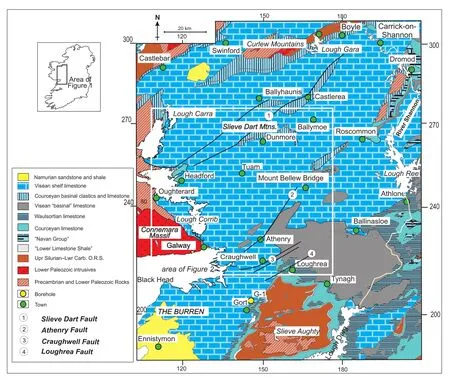

The study area includes a large terrane of flat-lying Lower Carboniferous (Mississippian) limestone in Co.Galway, western Ireland, approximately 2000 km2,extending from Lough Corrib in the west to the River Suck (Ballinasloe) in the east, and from Ballymoe and the Slieve Dart Fault in the north to Craughwell and Loughrea in the south (Figure 1). It represents part of an extensive carbonate platform (“Galway-Roscommon Shelf ” in Morriset al., 2003; Nagyet al., 2005 or “Tuam Block”in Longet al., 2004), adjacent to the older Precambrian and Lower Paleozoic Connemara Massif to the northwest of Galway city. Exposures are very limited and much of the area is covered by glacial and fluvioglacial sediments;the best sections are in the limestone quarries close to Galway city (Pracht and McConnell, 2012). The most recently published maps of the area (1:100,000; Prachtet al., 2004; Longet al., 2004) show that the majority of the exposed limestones are of Viséan age and mainly depicted as undifferentiated shelf carbonates, with small isolated patches of Viséan basinal limestones.

Figure 1 Geological map of western Ireland (adapted from Long et al., 2004; Pracht et al., 2004). O.R.S. = Old Red Sandstone.

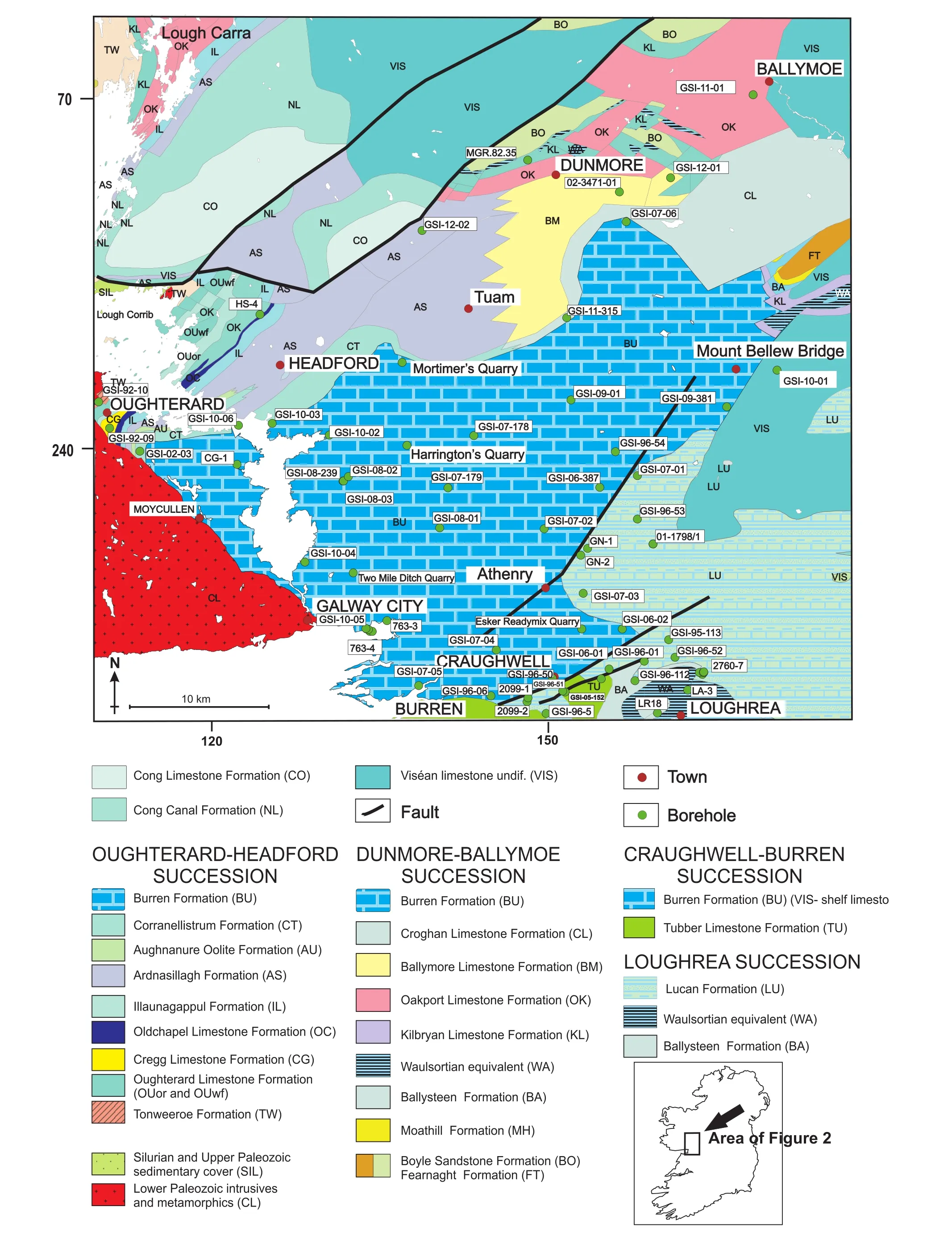

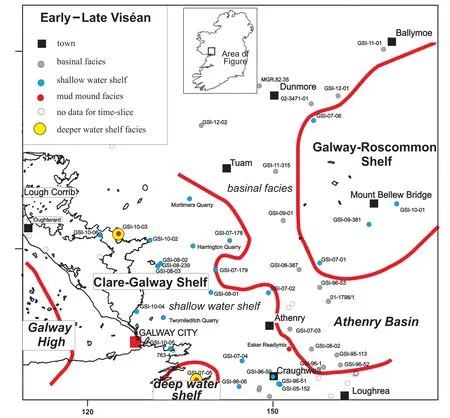

Recent investigations have attempted to differentiate this >800 m-thick Viséan carbonate succession into constituent formations, based on analysis of drillcore from several deep boreholes (>300 m thick) and many shorter boreholes (c.100 m thick) drilled by the Geological Survey of Ireland (GSI). In total, during the period from 2005 to 2012, 30 boreholes have been drilled within this region and logged in detail. Sampling of selected boreholes has been undertaken by the authors to determine the age of different stratigraphic units based on their macrofauna(corals) and microfossils (principally foraminifers and calcareous algae). Correlation between the deeper boreholes has recognized several distinct Viséan stratigraphic successions that clearly show lateral facies changes across the region. These comprise in the west the Oughterard-Headford succession around Lough Corrib, the Dunmore-Ballymoe succession in the northeast and centre, and further south the Craughwell-Burren succession (Figure 2). Also, in the southeast of the area, a transition from shelf to basin facies can be recognized, as well as an older Tournaisian succession with Waulsortian mud-mounds in the Loughrea-Tynagh area (Figures 1, 2).

The region has been affected by major NE- and ENE-trending Variscan faults with downthrows of hundreds of metres. The Athenry and Craughwell Faults juxtapose shelf and basinal successions, and the Loughrea Fault and Slieve Dart Fault expose inliers of basal Carboniferous siliciclastic rocks and Tournaisian (Courceyan) limestones(Prachtet al.,2004; Longet al.,2004; Pracht and McConnell, 2012; Figures 1, 2).

The main aim of this study is a synthesis of the newly acquired borehole data from the 30 recently drilled GSI boreholes integrated with older borehole data on file in the GSI (28 boreholes; comprising 14 drilled by GSI and 14 non-GSI commercial drillholes), together with new field data we have collected. The result of collating data from the 58 boreholes is a much improved and detailed geological map and lithostratigraphy of the region (Figure 2), with an attempt to show the areal distribution of Viséan formations tied to key boreholes and outcrops.Also, a wealth of microfacies and micropalaeontological data from the limestones has been gathered and used to help characterize and date the various formations, and to correlate them within the region and with other type sections and boreholes outside the study area. These are principally from the Burren region of Co. Clare and Gort Borehole (G-1) in southern Co. Galway in the southwest,and around Boyle, Co. Roscommon and Carrick-on-Shannon, Co. Leitrim to the northeast (Figure 1). Finally, analysis is made of the carbonate depositional environments and palaeogeographic maps are reconstructed for the region.

2 Lithostratigraphy, biostratigraphy and microfacies

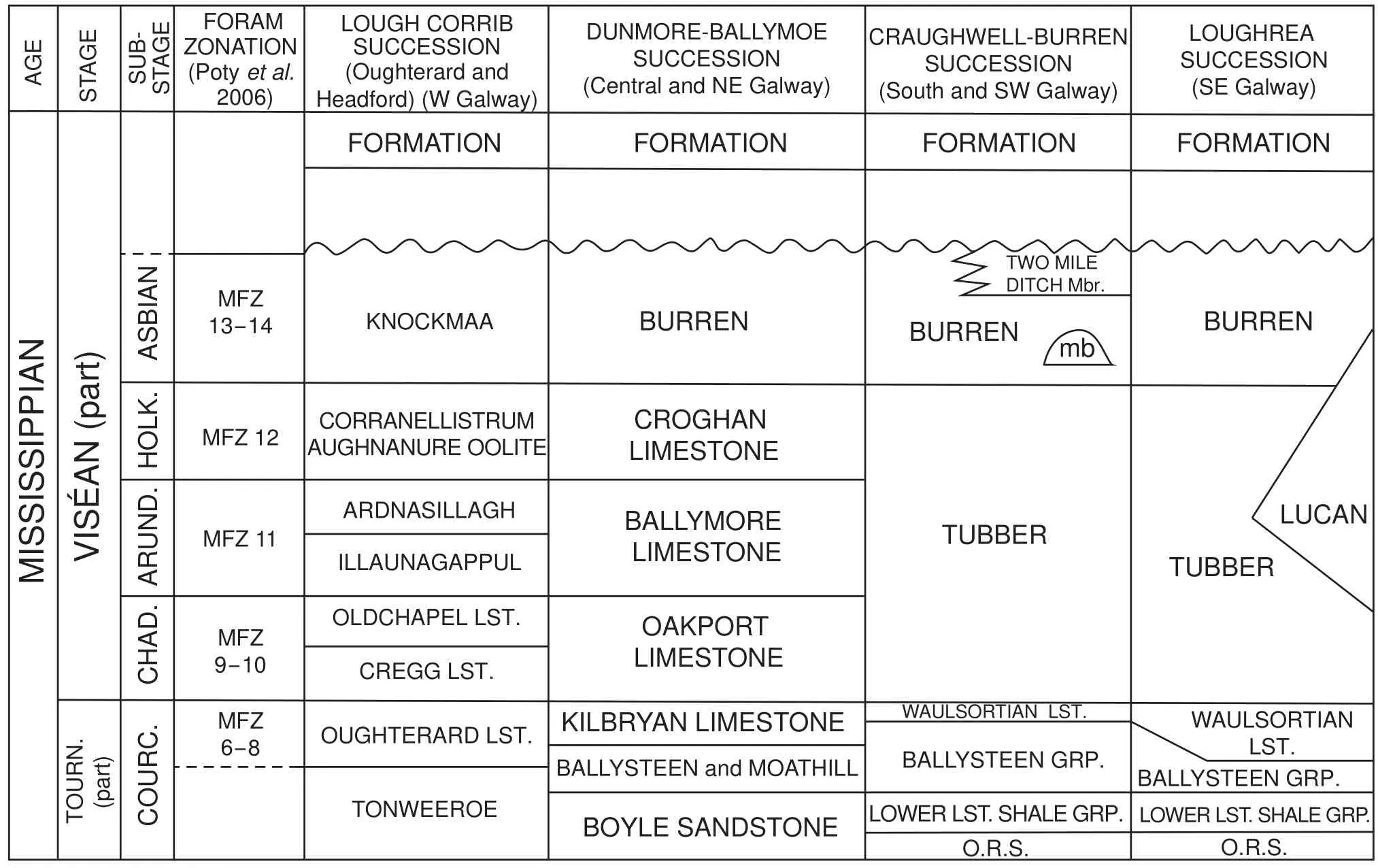

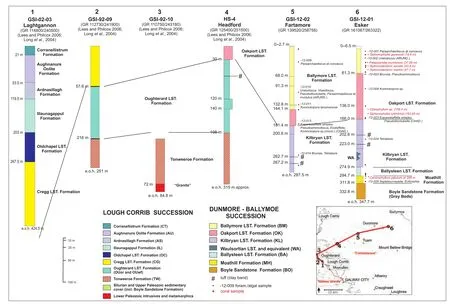

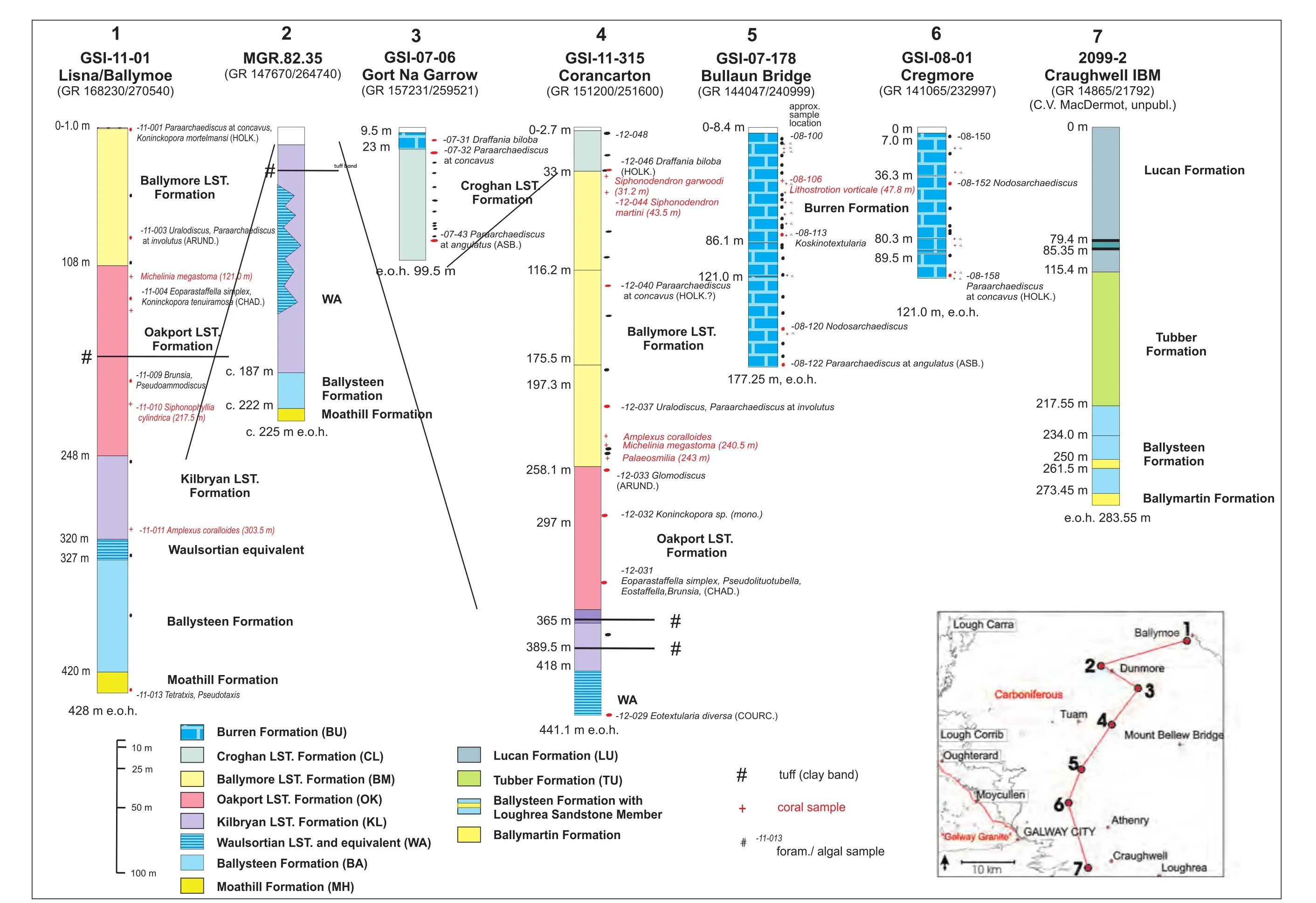

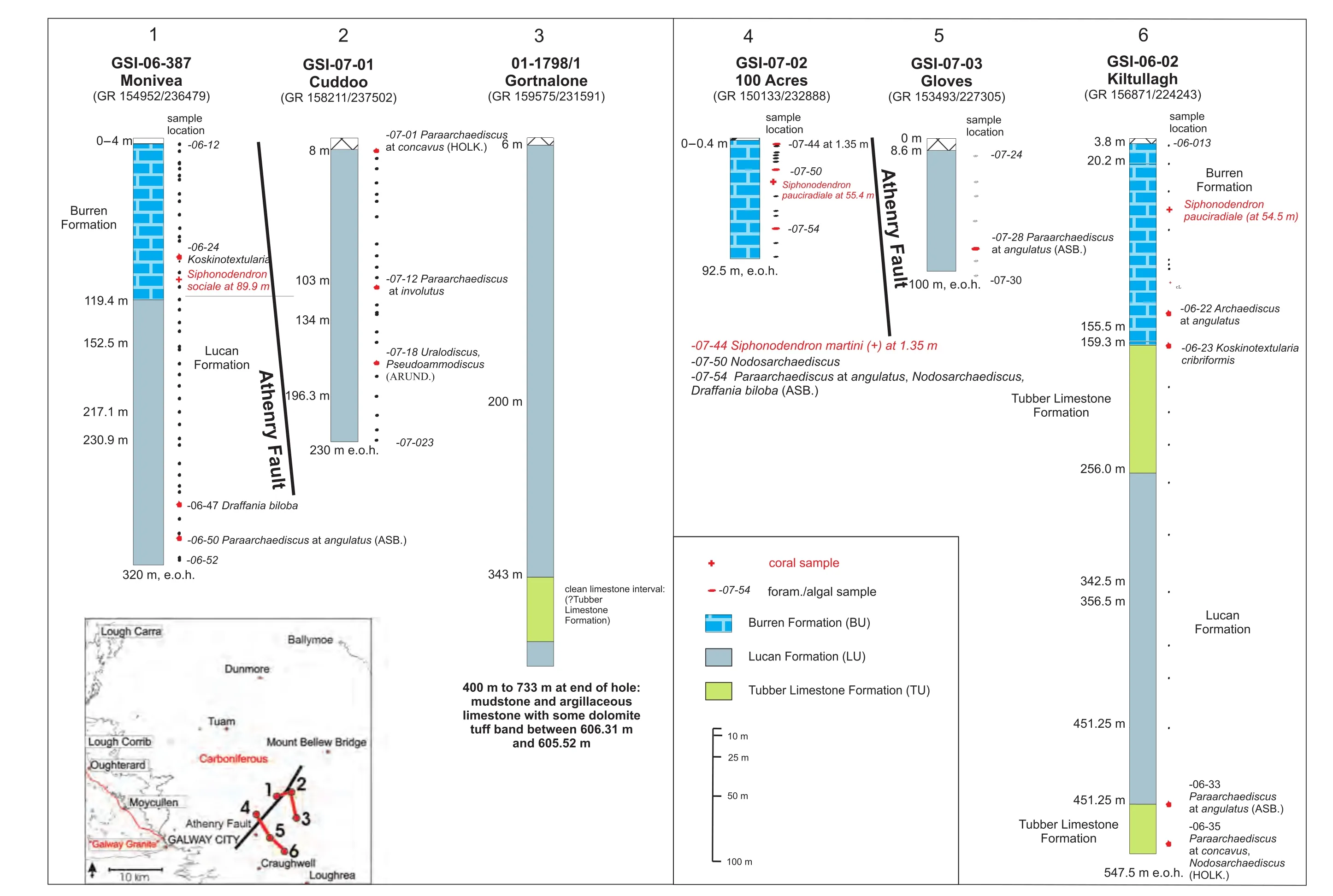

Succeeding the basal Carboniferous siliciclastic units and Tournaisian limestones, four distinct Viséan lithostratigraphic successions have been recognized within the study area (Table 1). In the northeast and central part of the region is the Dunmore-Ballymoe succession, identified in the Esker (GSI-12-01), Fartamore (GSI-12-02),Lisna (GSI-11-01), Corancarton (GSI-11-315) and Bullaun Bridge (GSI-07-178) boreholes (Figures 2, 3).The stratigraphic units identified are closely comparable to the succession defined by Caldwell (1959) from the Carrick-on-Shannon Syncline, 40 km to the northeast in counties Roscommon and Leitrim (Figure 1, Table 1),which crops out between Boyle and Carrick-on-Shannon.In the western part of the region is the Oughterard-Headford (Lough Corrib) succession, based on boreholes(HS-4, GSI-02-03, GSI-92-09, GSI-92-10; Figure 2) and outcrops around the shores of Lough Corrib (Prachtet al.,2004; Longet al., 2004). In the south of the region is the Craughwell-Burren succession, identified in GSI-06-02,GSI-06-387, GSI-07-179, GSI-08-239, GSI-10-04 and GSI-96-50 boreholes (Figures 2, 5) and comparable to the Burren-Gort succession in south Co. Galway and north Co. Clare (Prachtet al.,2004; Gallagheret al.,2006).In addition, thick Viséan basinal successions are present in the southeast of the region recognized in GSI-07-01(Cuddoo), GSI-07-03 (Gloves), 2099-2 and 01-1798/1 boreholes (Figures 4, 5) (Loughrea succession).

Figure 2 Geological map of Co. Galway and location of selected boreholes and localities mentioned in the text. The three main stratigraphic successions are also highlighted.

Table 1 Revised Mississippian lithostratigraphy for Co. Galway showing lateral equivalence of the main successions (Modified and updated from Morris et al., 2003; Pracht et al., 2004; Pracht and McConnell, 2012). Abbreviations: TOURN. = Tournaisian, COURC. =Courceyan, CHAD. = Chadian, ARUND. = Arundian, HOLK. = Holkerian, MFZ = Mississippian foraminiferal zone, Mbr. = Member,mb = mud?mound (bioherm/buildup), O.R.S. = Old Red Sandstone, LST. = limestone, GRP. = Group.

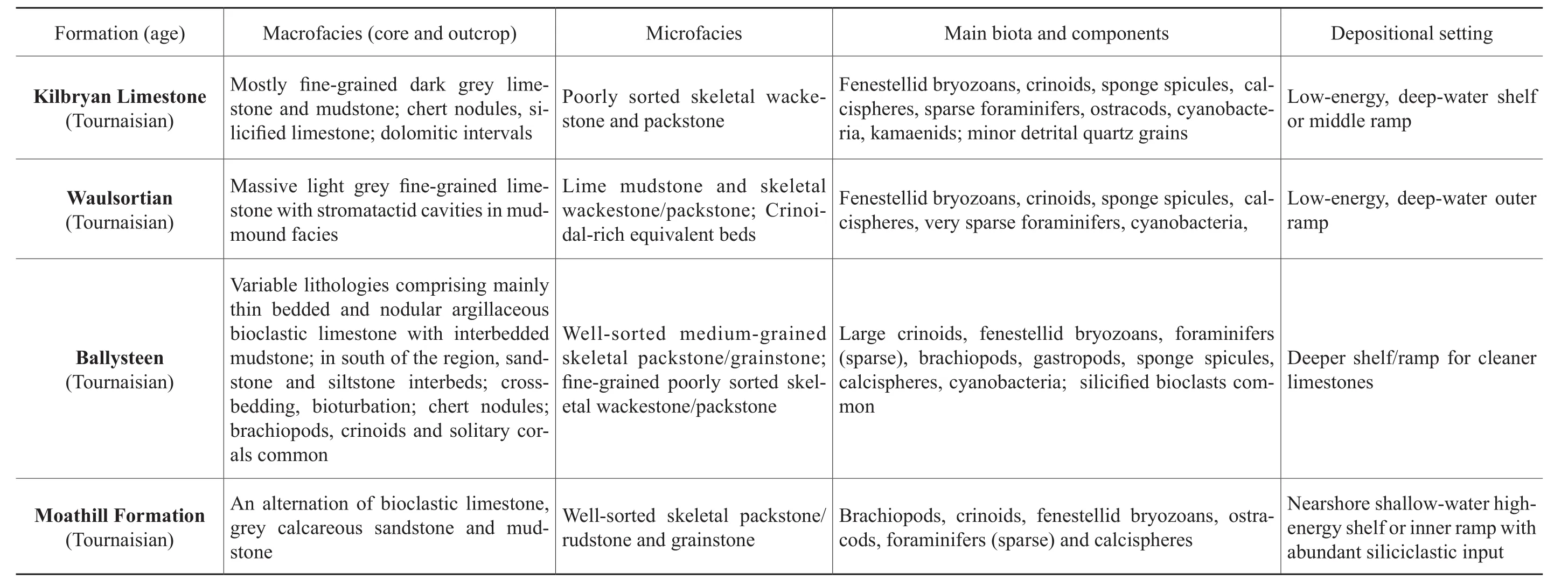

The description of the various Lower Carboniferous formations is from oldest to youngest, beginning with the basal siliciclastic and limestone formations of Tournaisian age. These are only briefly described, as the main focus of this paper is on the younger Viséan formations, which areally account for the majority of the region. More comprehensive descriptions of these Tournaisian units can be found in Prachtet al.(2004). Also, as the Viséan limestone formations defined around the shores of Lough Corrib in the west of the region can be directly equated to the limestone succession further east (see Table 1), only details of the stratigraphy in the Dunmore?Ballymoe area,which is regarded as the standard succession for most of the Galway?Roscommon Shelf (see Morriset al., 2003),is documented here. More detailed descriptions of the Lough Corrib succession can be found in Prachtet al.(2004). Biostratigraphic dating of the Tournaisian and Viséan limestones has been achieved principally using foraminifers. The assemblages have been assigned to the standard Mississippian foraminiferal biozones MFZ 6-MFZ 14 of Potyet al.(2006; Table 1) (broadly equivalent to the former Cf2-Cf6? zones and subzones, as used in Jones and Somerville, 1996). Important characteristics of the limestone microfacies are summarized in Table 2,based on an examination of over 400 thin sections.

2.1 Basal Carboniferous siliciclastic units

In the north of the region, the basal siliciclastic unit is identified as the Boyle Sandstone Formation, which forms inliers in Slieve Dart and Castlerea and has its type section near Boyle, Co. Roscommon (Caldwell,1959; Morriset al., 2003) where it isc.105 m thick. It is represented in GSI?12?01 by >30 m of grey sandstone. Its lateral equivalent in the western Lough Corrib succession(GSI?92?10 and HS-4) is the Tonweeroe Formation(>115 m thick) which shows a lower red?bed sandstone and conglomerate sequence passing up to grey bioturbated sandstones and mudstones (Figure 2). In GSI?92?10 borehole the Tonweeroe Formation rests directly on the Silurian-Devonian Galway granite. The age of the Boyle Sandstone Formation has been confirmed as late Tournaisian based on spore data (CM Zone) from the type section (Morriset al., 2003). In GSI?12?01 the Boyle Sandstone Formation is followed by marine limestones of the Moathill Formation (Figures 2, 3). In the southern boundary of the study region a thicker and more complete Tournaisian succession is preserved around Craughwell(2099-2) and Loughrea (Figure 1). There, continental red bed sediments pass up to a transitional marine succession(Lower Limestone Shale Group) developed around the margin of the Slieve Aughty Inlier (Figure 1), succeeded by an open marine limestone succession (Ballysteen Group) (Table 1), typical of the Gort borehole (G-1) in the Limerick Province (see Philcox, 1984; Somerville and Jones, 1985; Sleeman and Pracht, 1999; Somerville and Waters, 2011; Somervilleet al.,2011).

Figure 3 Correlation of boreholes from west to east across northern Co. Galway with important coral taxa (in red) andmicrofossils indicated. Abbreviations: e.o.h. =end of hole, LST. =Limestone, CHAD. =Chadian, ARUND. =Arundian.

Figure 4 Correlation of boreholes from north to south across Co. Galway with important coral taxa (inred) andmicrofossils indicated. Abbreviations: e.o.h. =end of hole, COURC. =Courceyan, CHAD. =Chadian, ARUND. =Arundian, HOLK. =Holkerian, ASB. =Asbian.

Figure 5Correlation of boreholes in southern and southeastern Co. Galway to show platform-basin transitions with important coral taxa (in red) and microfossils indicated. Abbreviations:e.o.h. =end of hole, ARUND. =Arundian, HOLK. =Holkerian, ASB. =Asbian.

Table 2 Characterization (macrofacies, microfacies andinterpretation of depositional facies) of late Tournaisianand Viséan limestone formations in the Co. Galway region, arranged in approximately stratigraphical order (oldest at the base). The limestones are classified according to the Dunham, 1962 scheme (modified by Embry and Klovan, 1971).

Table 2 , continued

2.2 Moathill Formation

This formation comprises an alternation of bioclastic limestone, grey calcareous sandstone and mudstone. It isc.15 m thick in GSI-12-01 in the north of the region (Figure 2). It represents the local transitional unit into the succeeding limestone-dominant Ballysteen Formation. The Moathill Formation forms part of the Navan Group which is better developed east of the River Shannon in Co. Longford (Morriset al.,2003; Somerville and Waters, 2011).

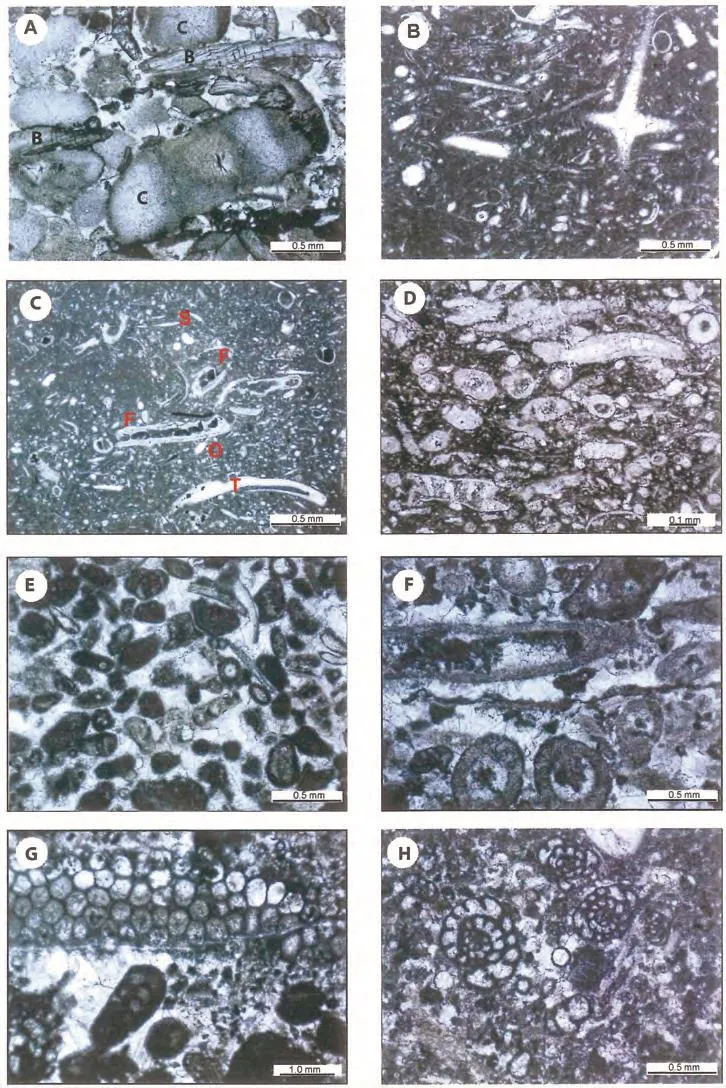

Microfacies: The limestones typically comprise moderately well-sorted, coarse-grained skeletal grainstone/rudstone (Figure 6A). The main skeletal components are brachiopods, crinoids, fenestellid bryozoans, ostracods,algae (Kamaena), foraminifers and calcispheres.

Depositional setting: The formation was deposited in a nearshore, shallow-water siliciclastic-dominant shelf in which both fine- and coarse-grained clastic sediments accumulated. Periodically, shelf limestones with a rich and diverse benthic biota developed, when siliciclastic input onto the shelf was reduced. High-energy conditions prevailed during the formation of the limestones, as suggested by the good sorting and rounding of skeletal material.

Age:The Moathill Formation is late Tournaisian in age, based on a sparse foraminiferal assemblage includingEndothyra, Septatournayella, Earlandia, Eoforschia(MFZ 6), and algal/cyanobacteria and microproblematica(Girvanella, Salebra sibirica).

2.3 Ballysteen Formation

This formation comprises light-grey and dark-grey,fine-grained argillaceous bioclastic limestone alternating with calcareous mudstone. The limestones are often bioturbated and chert nodules are commonly developed.Rare large solitary rugose corals and crinoids are the main macrofaunal elements. Identified taxa include: Caninophyllum patulum, Sychnoelasma,andAmplexizaphrentis.In the northeast of the region, in GSI-11-01, the Ballysteen Formation is nearly 100 m thick (Figure 4), but thins westwards around Dunmore (c.35 m in MGR.82.35 and 20 m in GSI-12-01 respectively; Figures 3, 4). In the south of the region near Craughwell (2099-2), the Ballysteen Formation is also thin (c.56 m), but thickens southeast to Loughrea where it isc.168 m (Prachtet al.,2004) and contains oolitic and sandy intervals. In the south of the region near Gort, the Ballysteen Formation together with the Ballymartin Formation form the Ballysteen Group(Somervilleet al.,2011).

Microfacies: Typically poorly sorted skeletal wackestone/packstone and grainstone. The main skeletal components are crinoids, brachiopods, fenestellid bryozoans,sponge spicules, algae (Kamaena), sparse foraminifers,gastropods and calcispheres. Partial silicification of bioclasts is common.

Depositional setting: The Ballysteen Formation was deposited mostly in an offshore shelf/middle ramp, below fairweather wave-base but above storm wave-base,in which fine-grained siliciclastic sediment accumulated.The biota is rich and diverse with abundant large crinoids,brachiopods and solitary corals. The lack of sedimentary structures, poor sorting of bioclasts and abundance of bryozoans implies low-energy, relatively quiet water conditions. Locally, though, in the Loughrea area, shallower water, higher energy conditions developed with the presence of ooids and better sorting of bioclasts.

Age:The Ballysteen Formation is late Tournaisian in age based on a sparse foraminiferal assemblage includingEoforschia, Septatournayella, Earlandia, Eblanaia(MFZ 6), and algal/cyanobacteria and microproblematica(Parachaetetes, Girvanella, Salebra sibirica).

2.4 Waulsortian Limestone Formation

Within the study area, the Waulsortian Limestone Formation mainly occurs around Loughrea in the southeast,where it reaches a thickness ofc.500 m (Prachtet al.,2004). Although no boreholes in the recent drilling programme encountered this unit, further to the north in the Slieve Dart Borehole (02-3471-01; Figure 2), 45 m of Waulsortian Limestone were recorded (Morriset al.,2003). The dominant Waulsortian lithology is pale-grey,massive limestone, which, at outcrop in eastern Galway,forms large mud-mounds several tens of metres in thickness (Lees, 1964, 1994; Lees and Miller, 1985, 1995).There is a sharp basal contact with dark grey argillaceous limestones of the Ballysteen Formation. In the Loughrea area it is succeeded by either the Tubber Formation (see below) or basinal facies (Lucan Formation), but in the northern part of the region it is overlain by and is partly equivalent to the Kilbryan Limestone Formation (Morriset al.,2003; Table 1). In some boreholes (GSI-12-01,GSI-11-01, GSI-11-315 and MGR.82.35) where typical massive pale-grey micritic Waulsortian limestone is not developed, a thinly-bedded, fine-grained nodular limestone and shale unit is present and referred to as ‘Waulsor-tian equivalent’ (Figures 3, 4). The latter unit is differentiated from the Kilbryan Limestone Formation by its higher proportion of limestone to mudstone.

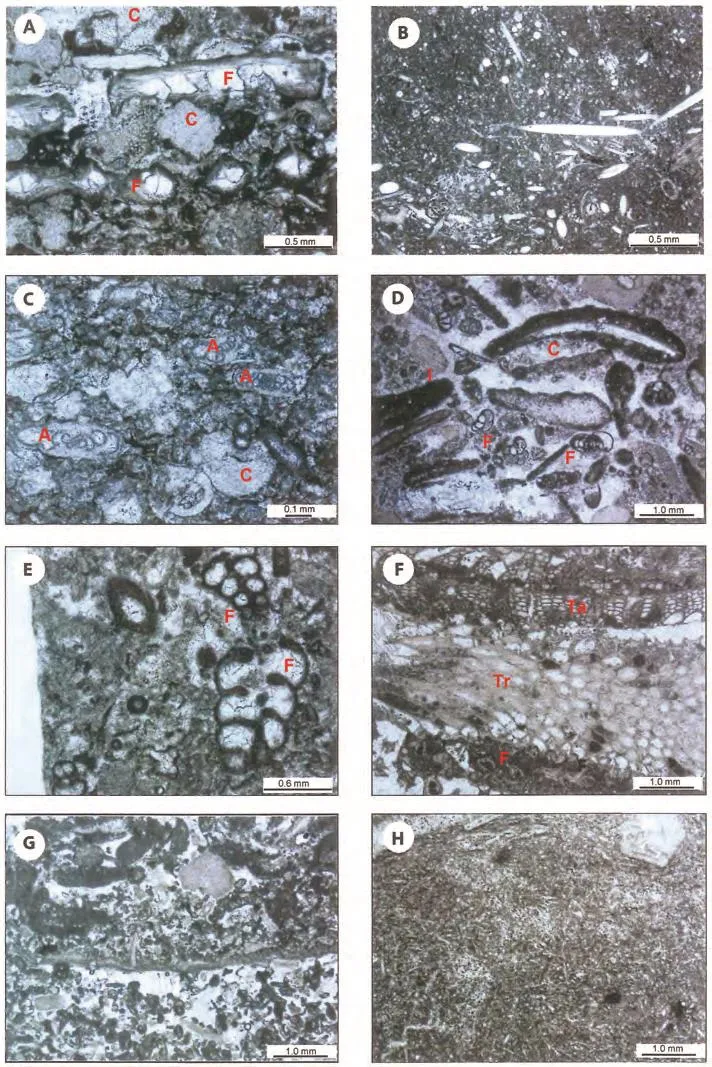

Figure 6 Photomicrographs of carbonate microfacies (all in plane polarized light) of late Tournaisian and early Viséan limestones. A-Skeletal grainstone with crinoids (C) and brachiopods (B) in sparry calcite cement, Moathill Formation, Esker Borehole(GSI-12-01), 300.2 m; B-Spiculitic wackestone, with monaxin and hexactin calcitic spicules in lime mud matrix, Waulsortian equivalent, Corancarton Borehole (GSI-11-315), 440.9 m; C-Skeletal wackestone with fenestellid bryozoans (F), sponge spicules (S),trilobites (T) and ostracods (O) in lime mud matrix, Waulsortian equivalent, Corancarton Borehole, 440.9 m; D-Skeletal wackestone with kamaenids and ostracods in lime mud matrix, Kilbryan Limestone Formation, Corancarton Borehole (GSI-11-315), 379.2 m; ESkeletal peloidal intraclastic grainstone with moderately well-sorted micritized bioclasts in sparry calcite cement, Oakport Limestone Formation, Corancarton Borehole (GSI-11-315), 290.1 m; F-Skeletal grainstone with abundant tubular problematicum Luteotubulus in sparry calcite cement, Oakport Limestone Formation, Fartamore Borehole (GSI-12-02), 177.1 m; G-Skeletal intraclastic packstone with dasyclad alga Koninckopora (K) sp. (monolaminar) and foraminifers (F) in sparry calcite cement, Oakport Limestone Formation,Fartamore Borehole (GSI-12-02), 144.5 m; H-Skeletal packstone with abundant foraminifers and calcispheres in sparry calcite cement and lime mud, Oakport Limestone Formation, Esker Borehole (GSI-12-01), 64 m.

Microfacies: The characteristic lithology of the Waulsortian equivalent is wackestone with crinoids, fenestrate bryozoans, sponge spicules, trilobites, brachiopods and molluscs (Figure 6B, 6C). In the lime mudstone of the mud-mounds, large spar-filled cavity structures (stromatactis), ranging up to many centimetres across, are commonly developed (Lees, 1964, 1994; Lees and Miller,1985, 1995; Somerville, 2003), and foraminifers are rare.

Depositional setting: The mud mounds characteristic of this formation developed in a deep-water distal ramp setting below storm wave-base. Low-energy conditions prevailed during the formation of the massive limestones and their laterally equivalent bedded limestones dominated by crinoids, sponges and bryozoans.

Age:The Waulsortian Limestone is late Tournaisian in age based on very limited foraminiferal and conodont data(Sevastopulo, 1982; Prachtet al.,2004).

2.5 Kilbryan Limestone Formation

The Kilbryan Limestone Formation (Caldwell, 1959;Morriset al., 2003) consists of dark-grey, fine-grained argillaceous bioclastic limestone alternating with minor mudstone and some chert nodules. The lower part of the formation shows a nodular bedding, bioturbation,geopetals and dewatering structures. It also contains two thin green clay bands in GSI-12-02 (at 262.7 m and 267.2 m) in GSI-12-01 (at 202.6 m and 223 m) and in GSI-11-315(at 365.0 m and 389.5 m) (Figures 3, 4). One of these may possibly correlate to the clay band in HS-4 (atc.75 m;Figure 3) and the one in MGR.82.35 (atc.33 m; Figure 4). These clay bands have been interpreted elsewhere as decomposed volcanic ashes (tuffs) (Philcox, 1984; Morriset al., 2003). The upper boundary to the overlying Oakport Limestone Formation is transitional, with light-grey limestone increasing in proportion to argillaceous limestone for tens of metres. The Formation is 108 m thick in GSI-12-01 compared toc.185 m in MGR.82.35. Further west near Headford (Longet al., 2004), the Kilbryan Limestone Formation is laterally correlated to the Oughterard Limestone Formation of the Lough Corrib succession and is 166 m in HS-4 (Figure 3, Table 1). The macrofauna comprises rare large solitary rugose corals (Amplexus coralloides) and tabulates (Syringopora).

Microfacies: Typically moderate to well-sorted skeletal wackestone (commonly with microsparite matrix)and poorly sorted skeletal packstone. The main skeletal components are crinoids, fenestellid bryozoans, sponge spicules, algae (Kamaena)(Figure 6D), foraminifers, cyanobacteria coating shells, trilobites and calcispheres.

Depositional setting: The formation was deposited in a moderately deep-water shelf/mid ramp, below storm wave-base, in which both fine-grained clastic mud and carbonate mud accumulated. Low-energy conditions prevailed during the deposition of the fine-grained muddy limestones. The benthic biota is quite rich and diverse and locally kamaenid algae and ostracods can be abundant.

Age:The Kilbryan Limestone Formation lacks diagnostic microfossils. Based on its stratigraphic position between the older Tournaisian-aged Ballysteen Formation(or Waulsortian Limestone Formation) and the overlying lower Viséan Oakport Limestone Formation, it is late Tournaisian to earliest Viséan in age.

2.6 Oakport Limestone Formation

The Oakport Limestone Formation (Caldwell, 1959;Morriset al., 2003) consists of light-grey, massive, coarsegrained bioclastic limestone with occasional intervals of dark-grey fine-grained fenestral lime mudstone; rare black shales and very rare green clay bands occur in the lower part. Chert nodules and bioturbation are occasionally developed. Large solitary rugose corals, tabulate corals, gastropods, brachiopods and crinoids are the main macrofaunal elements. Identified coral taxa include: Siphonophyllia cylindrica, Michelinia megastoma,andClisiophyllumsp.

The base of the Formation has been placed at the first appearance of light-grey bioclastic limestone above the underlying Kilbryan Limestone Formation. The top, also gradational, is placed at the incoming of argillaceous lithologies. The thickest interval of Oakport Limestone(140 m) is recorded in GSI-11-01 and GSI-12-01, similar to that in the Slieve Dart Borehole (02-3471-01; 137 m)(Figures 2, 3, 4; Morriset al., 2003). The Formation notably thickens and becomes more argillaceous from west(GSI-12-02) to east (GSI-12-01) (Figure 3). The Oakport Limestone Formation is laterally correlated to the Cregg Limestone and Oldchapel Limestone Formations in the Lough Corrib succession (Figure 3, Table 1). In HS-4,only the lower 28 m of Oakport Limestone Formation was drilled. In the central region near Tuam, the Oakport Limestone Formation thins to 110 m (GSI-11-315; Figure 4) but was not intersected in boreholes further to the south.

Microfacies: Typically moderate to well-sorted, intraclastic, skeletal peloidal wackestone and packstone with occasional intraclastic skeletal grainstone (Figure 6E) and rare ooids in the upper beds. The main skeletal compo-nents are locally abundant problematica (Luteotubulus,Figure 6F), dasycladacaean algae (Koninckopora(Figure 6G) andKamaena), endothyroid foraminifers (rich and diverse in the lower beds, Figure 6H), cyanobacteria coating shells, calcispheres, crinoids and micritized bioclasts.

Depositional setting: The Oakport Limestone Formation was deposited in a shallow-water shelf setting above fairweather wave-base. The presence of rounded intraclasts, ooids, micritized bioclasts and peloids in wellsorted coarse-grained limestones attests to high-energy conditions. However, the formation also contains fenestral and burrowed lime mudstones, which indicate deposition in low-energy intertidal lagoonal environments protected by ooid and skeletal grainstone shoals. The biota is rich and diverse with abundant crinoids, foraminifers and dasycladacean algae, the latter suggesting growth in a shallow photic zone.

Age: The Oakport Limestone Formation is early Viséan(Chadian) in age, based on the presence of the key foraminifers:Eoparastaffella simplex,Pseuodolituotubella,Brunsia, Pseudoammodiscus,Eblanaia michoti, Eostaffella(an assemblage characteristic of MFZ 9),as well asthe algaKoninckoporasp.(monolaminar wall)and abundantLuteotubulus.

2.7 Ballymore Limestone Formation

The Ballymore Limestone Formation (Caldwell, 1959;Morriset al., 2003) attains its greatest thickness (225 m)in GSI-11-315 (Figure 4), which is thicker than in the type section (c.170 m) at Ballymore House near Boyle(Caldwell, 1959). It consists predominantly of dark-grey well-bedded and nodular fine-grained argillaceous limestone showing common bioturbation, with occasional intervals of massive, light-grey, coarse-grained limestone.The middle of the formation includes thicker calcareous shale intervals. Chert nodules are commonly developed.Large solitary rugose corals, fasciculate rugose and tabulate coral colonies, bellerophontid gastropods, brachiopods and sparse crinoids are the main macrofaunal elements. Identified taxa include: Siphonophyllia garwoodi,Michelinia megastoma, Siphonodendron martini, S. sociale, Palaeosmilia murchisoni,andAmplexus coralloides.The Ballymore Limestone Formation is laterally correlated to the Ardnasillagh Formation in the Lough Corrib succession and differs mainly in having less chert (Table 1). It is succeeded conformably by the Croghan Limestone Formation.

Microfacies: Comprises poorly sorted intraclastic skeletal wackestone/packstone/grainstone (Figure 7A, 7D),moderate to well-sorted skeletal peloidal packstone/grainstone, and spiculitic wackestone (Figure 7B). The main skeletal components include: crinoids, fenestellid bryozoans, sponge spicules, sparse dasycladacaean algae (monolaminar and bilaminarKoninckoporaandKamaena),mostly sparse foraminifers, although small archaediscids can be locally abundant (Figure 7C), rare red algae (aoujgaliids), calcispheres, problematica (salebrids) and very rare ooids/coated bioclasts.

Depositional setting: The Ballymore Limestone Formation was deposited in a moderately deep-water shelf below fairweather wave-base but above storm wave-base. Also,the formation comprises mainly fine-grained limestones interbedded with thick mudstone intervals which would have accumulated in a low-energy shelf setting. The biota is rich and diverse with crinoids, fenestellid bryozoans and sponge spicules, suggesting mainly quiet water, low-energy conditions. However, the development of occasional coral biostromes and sparse dasyclad green and red algae implies more turbulent conditions in a shallower photic zone.

Age: The Ballymore Limestone Formation is early Viséan (Arundian) in age, based on the presence of the key foraminifers:Uralodiscus,Paraarchaediscusatinvolutusstage,Glomodiscus, Valvulinella,andForschia(typical of MFZ 10-11), as well as the dasyclad algaKoninckopora tenuiramosa,and species ofthe rugose coralSiphonodendron.At its type locality, the age of the Ballymore Limestone Formation is Arundian to Holkerian (Morriset al.,2003).

2.8 Croghan Limestone Formation

The Croghan Limestone Formation (Caldwell, 1959;Morriset al., 2003) is thickest in Gort Na Garrow Borehole (>77 m) (GSI-07-06), near Dunmore and is also present in GSI-11-315 (Figure 4) in the north of the region.In the type section at Cavetown Lough near Boylec.107 m are recorded (Caldwell, 1959; Morriset al., 2003). The formation comprises dark-grey, well-bedded, fine-grained argillaceous limestone showing frequent bioturbation, with occasional intervals of massive, light-grey, coarse-grained limestone. Chert nodules are commonly developed. The main macrofaunal elements are large solitary rugose corals, fasciculate rugose and tabulate coral colonies, bellerophontid gastropods, brachiopods and sparse crinoids.Identified taxa include: Siphonophyllia garwoodi, Micheliniasp.,Siphonodendron martini,andCraveniasp.The Croghan Limestone Formation is laterally correlated to the Corranellistrum Formation in the Lough Corrib suc-cession and succeeded conformably by the Burren Formation (Table 1).

Figure 7 Photomicrographs of carbonate microfacies (all in plane polarized light) of early to late Viséan limestones. A-Skeletal packstone with closely packed bioclasts, mostly fenestellid bryozoans (F) and crinoids (C) in sparry calcite cement, Ballymore Limestone Formation, Corancarton Borehole (GSI-11-315), 256.5 m; B-Spiculitic wackestone, with monaxon calcitic spicules and ostracods in lime mud matrix, Ballymore Limestone Formation, Corancarton Borehole (GSI-11-315), 208.6 m; C-Skeletal packstone with crinoids (C) and archaediscid foraminifers (A) in sparry calcite cement, Ballymore Limestone Formation, Lisna Borehole (GSI-11-01),2.5 m; D-Intraclastic-skeletal grainstone with intraclasts (I), foraminifers (F) and cyanobacterial coating on shells in sparry calcite cement, Ardnasillagh Limestone (Ballymore Limestone) Formation, Fartamore Borehole (GSI-12-02), 133.1 m; E-Skeletal packstone/grainstone with bilaminar palaeotextulariid foraminifers (F) in sparry calcite cement, Burren Formation, Keekil Borehole (GSI-10-03),99.7 m; F-Bryozoan-rich boundstone with trepostomes (Tr), encrusting tabuliporids (Ta) and fenestellids (F) in lime mud matrix with patches of sparry calcite cement, Burren Formation, Keekil Borehole (GSI-10-03), 129.75 m; G-Poorly sorted skeletal, intraclastic grainstone with crinoids, brachiopods, micritized bioclasts and peloids in sparry calcite cement, Tubber Formation, Killsolan Borehole(GSI-10-01), 109.8 m; H-Fine-grained spiculitic wackestone, with dense nework of spicules in lime mud matrix, Lucan Formation,Monivea Borehole (GSI-06-387), 152.5 m.

Microfacies: Comprises poorly sorted skeletal wackestone and packstone (with microspar matrix), and rare skeletal grainstone. The main skeletal components are crinoids, fenestellid bryozoans, sponge spicules, trilobites,rare red algae (aoujgaliids), foraminifers, (small archaediscids can be locally abundant), calcispheres, problematica (Draffaniaand salebrids) and kamaenids.

Depositional setting: The Croghan Limestone Formation was deposited in a moderately deep-water shelf setting, similar to that of the Ballymore Limestone. Also,the formation comprises mainly fine-grained argillaceous limestones which would have accumulated in a low-energy shelf. The biota is rich and diverse with crinoids, fenestellid bryozoans, sponge spicules, solitary corals, algae and foraminifers.

Age: The Croghan Limestone Formation is middle Viséan (Holkerian) in age, based on the presence of the key foraminifers:Paraarchaediscusatconcavusstage,Eostaffella, Valvulinella, Forschia(MFZ 12),the dasyclad algaKoninckopora tenuiramosa,andDraffania biloba. At its type locality the age of the Ballymore Limestone Formation is Holkerian to Asbian (Morriset al.,2003).

2.9 Burren Formation

The Burren Formation (Prachtet al.,2004; Gallagheret al., 2006) is present in boreholes GSI-10-03, GSI-10-04,GSI-10-05, GSI-07-05, GSI-07-06 and GSI-07-179 with its greatest thickness (>244 m) in Castlequarter Borehole (GSI-08-239). The formation occupies most of the low-lying ground north of Galway city towards Tuam.It was formerly quarried around Angliham and Menlough on the southern shores of Lough Corrib, and is currently well exposed in the working quarries at Two Mile Ditch (GR 132870/229237), Harrington’s Quarry (GR 138281/240201), Mortimer’s Quarry (GR 137553/248535)and Esker Readymix Quarry (GR 153450/224105) (Figure 2). As a result of the recent drilling programme, it is now recognized that the Burren Formation, although in places more argillaceous than in its type locality in the Burren region in Co. Clare, can be extended northwards into south and central Co. Galway (Pracht and McConnell, 2012).Furthermore, it is also recognized that the Two Mile Ditch Member, representing the upper part of the Burren Formation, with a type section in Two Mile Ditch Quarry, is laterally equivalent to the Aillwee Member of the Burren region (Prachtet al.,2004; Gallagheret al., 2006). In the type section, the Burren Formation isc.400 m thick and the Aillwee Member isc.150 m thick (Gallagher, 1992).The Burren Formation was previously referred to as the Knockma Formation (Longet al.,2004), but is here incorporated in the Burren Formation. In the type area and much of south Co. Galway (e.g.Kiltullagh Borehole GSI-06-02;Figure 5) the Burren Formation succeeds the Tubber Formation (Prachtet al.,2004; Gallagheret al., 2006), but over much of north Co. Galway it rests conformably on the Croghan Limestone Formation (as in GSI-07-06, Figure 4). However, in the southeast of the region it interfingers with and succeeds the basinal facies of the Lucan Formation, as in Monivea Borehole (GSI-06-387) (Figure 5; see Table 1). The top of the Burren Formation and its contact with the overlying Slievenaglasha Formation are not present in the study area.

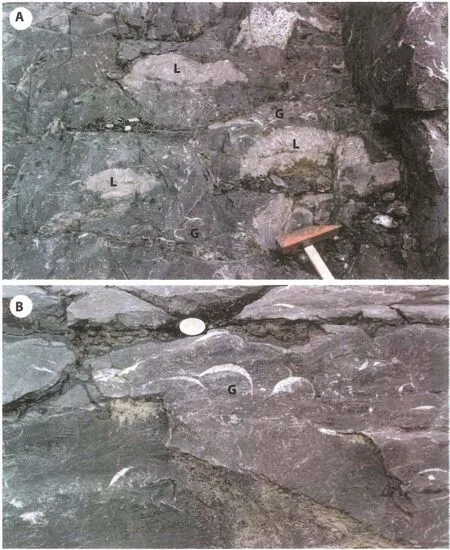

Typically, the limestones of the Burren Formation are pale grey and thickly-bedded to massive, but there are also intervals that are darker grey, medium-bedded and cherty.The Formation also comprises black calcareous shales interbedded with bioclastic limestone in the lower part. In the Two Mile Ditch Member, there are a number of clay bands that can be observed in quarry sections resting often on an irregular palaeokarstic surface (Figure 8A, 8B).In two boreholes (GSI-07-05 and GSI-10-03, Figure 2)mud-mound facies lithologies >35 m thick have been encountered, but these mounds are not exposed at outcrop.The macrofauna in the Burren Formation is dominated by numerous coral colonies ofSiphonodendron sociale,S. pauciradialeandLithostrotionvorticale(Figure 9A),with crinoids and large gigantoproductid brachiopods often concentrated in bands at the base and near the top of beds. These brachiopods often occur in a convex-upward orientation, especially near the top of beds (Figure 9B).

Microfacies: The bedded limestones comprise skeletal wackestone, packstone and grainstone (Figure 7E). The mud-mounds are composed of fine-grained wackestone and have stromatactid cavities with radiaxial fibrous calcite (RFC) cement and peloidal mud. Locally the mounds are rich in trepostome (Leioclema), fistuliporid (Tabulipora) and fenestellid bryozoans and form boundstone fabrics (Figure 7F). The main skeletal components in the non-mound facies are crinoids, dasycladacean green algae(Koninckopora), red algae (aoujgaliids and ungdarellids),fenestellid bryozoans, foraminifers (palaeotextulariids(Figure 7E) and small archaediscids can be locally abundant), sponge spicules, calcispheres, problematica (Draffaniaand salebrids) and kamaenids.

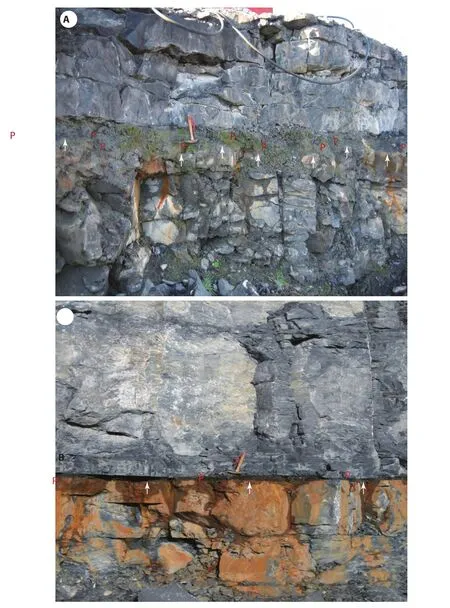

Figure 8 Well-bedded grey limestones of the Asbian Burren Formation (Two Mile Ditch Member) showing: A-An irregular palaeokarstic horizon (arrowed) with green clay wayboard (palaeosol, P) above infilling the topography; B-The palaeokarstic horizon is horizontal (arrowed) with conspicuous orange staining of limestones below the clay band (palaeosol, P). Two Mile Ditch Quarry.Scale: hammer is 40 cm long.

Figure 9 A-Right way up and inverted colonies of Lithostrotion vorticale (L) with overturned convex-up gigantoproductid brachiopods (G); B-Band of overturned convex-up gigantoproductid brachiopods (G). Burren Formation (Harrington’s Quarry). Scale:hammer head is 20 cm long; coin is 2.5 cm in diameter.

Depositional setting: The Burren Formation was deposited in a shallow-water shelf setting, mainly between fairweather- and storm wave-base, but with periodic shallowing events leading to temporary subaerial exposure. The latter is indicated by the developments of palaeokarstic surfaces and palaeosols, particularly in the upper part of the formation. The rich concentration of large brachiopods near the top and base of beds implies more turbulent higher energy conditions, especially when overturned in the hydrodynamically stable position. Abundant coral colonies suggest relatively shallow water within the photic zone, confirmed by the abundance of dasyclad algae and large robust thick-walled foraminifers. The occasional development of bryozoan-rich mud-mounds (buildups) suggests a quieter deeper water setting on the shelf.

Age:The Burren Formation is late Viséan (Asbian) in age (MFZ 13-14), and the Two Mile Ditch Member is late Asbian in age (MFZ 14) based on the presence of the diagnostic foraminifers:Paraarchaediscusatangulatusstage,Koskinotextularia cribriformis, Cribrostomum lecomptei,Palaeotextularia longiseptata,Lituotubella,Vissariotaxis,Pseudoendothyraand the red algaUngdarella uralica.At its type locality the age of the Burren Formation is Asbian and is succeeded conformably by the Brigantian Slievena-glasha Formation (Gallagheret al., 2006).

2.10 Tubber Formation

The Tubber Formation (Gallagher, 1996; Prachtet al.,2004), attains a maximum thickness of >292 m in Killasolan Borehole (GSI-10-01) in the east of the region near Mount Bellew Bridge (Figure 1), and isc.102 m thick near Craughwell (2099-2) in the south (Figure 4). It extends from the top of the Ballysteen Formation (or Waulsortian Limestone Formation if present) up to the base of the Burren Formation. It is well exposed in the type area around Tubber (c.8 km SSW of Gort) where it isc.300 m thick (Prachtet al.,2004). It represents most of the Viséan Burren-Gort succession below the Burren Formation and occurs mostly in the central and southern part of the region, south of Harrington’s Quarry. Further north it is probably laterally equivalent to the combined Oakport to Croghan Limestone Formations of the Dunmore-Ballymoe succession (Table 1).

The Tubber Formation is characterized by mediumgrey, crinoidal-rich limestone, with shaly partings at some levels and several chert horizons. Fasciculate colonies ofSiphonodendronare abundant in the upper part of the Tubber Formation (Prachtet al.,2004).

Microfacies: The Tubber Formation consists mostly of fine- to medium-grained, moderately well-sorted, skeletal and peloidal packstone and grainstone (Figure 7G) with some coarse-grained bioclastic grainstone intervals. The main skeletal components are crinoids, brachiopods, rare red algae (aoujgaliids), foraminifers, (small archaediscids can be locally abundant), calcispheres, problematica(Draffaniaand salebrids) and kamaenids.

Depositional setting: The Tubber Formation was deposited in a moderately shallow-water shelf, below fairweather wave-base but above storm wave-base. The presence of coarser-grained limestones with intraclasts and rounded bioclasts implies higher energy conditions. The biota is rich and diverse with abundant crinoids and common foraminifers, and elsewhere in the upper part of the formation are recorded coral biostromes.

Age: The Tubber Formation ranges in age from latest Tournaisian? to late Viséan (Chadian to Asbian substages).In the lower part of the formation the presence ofKoninckoporasp. (monolaminar alga) andEotextularia diversasuggests alatest Courceyan to Chadian age (MFZ 8-9). Higher in the formation the presence ofEoparastaffella simplex,Pseuodolituotubella,Brunsia, Pseudoammodiscus, Eostaffellaand absence of archaediscidsimply a Chadian age (MFZ 9). Important foraminiferal taxa recorded in boreholes GSI-09-381, GSI-96-51, GSI-05-152 and GSI-10-01 includeParaarchaediscusatinvolutusstage,Uralodiscus rotundus,U. settlensis,Glomodiscus,PlanoarchaediscusandParaarchaediscusatconcavusstage, which establish a late Arundian to Holkerian age(MFZ 10-12). In the highest beds of the formation below the Burren Formation in boreholes GSI-06-02, GSI-07-179 and GSI-08-239, the presence ofParaarchaediscusatangulatusstage,Paraarchaediscusatconcavusstage, andNodosoarchaediscus,as well asKoskinotextularia, Lituotubellaand theproblematicumDraffania bilobaimply a Holkerian to early Asbian age (MFZ 12-13).

2.11 Lucan Formation

The Lucan Formation represents rocks of basinal facies that are recorded in boreholes in the southeast of the region (GSI-06-02, GSI-06-387, GSI-07-01, GSI-07-03,GSI-95-113, 2099-2 and 01-1798-1). The greatest thickness (>733 m) is recorded in 01-1798-1. In Kiltullagh Borehole (GSI-06-02) 195 m of the Lucan Formation is recorded with rocks of the Tubber Formation above and below (Figure 5). In the Monivea Borehole (GSI-06-387),>200 m of the Lucan Formation is recorded below the Burren Formation. The Lucan Formation consists mainly of well-bedded, fine-grained, weakly laminated and bioturbated argillaceous limestone alternating with dark grey to black calcareous mudstone. Some limestone beds contain siliceous bands and pyrite is common. Rare slumped intervals are present.

Microfacies: Limestones comprise mainly wackestone and packstone with rare thin beds of grainstone. The main skeletal components are spicules (Figure 7H) and calcispheres, with crinoids, fenestellid bryozoans, ostracods and rare foraminifers, with an absence of algae, apart from kamaenids.

Depositional setting: The Lucan Formation was deposited in a deep-water, low-energy basinal setting. The presence of fine-grained limestones with abundant spicules and calcispheres, sparse foraminifers and absence of dasyclad algae confirms a depositional setting below the photic zone in quiet water, low-energy conditions. The presence of detrital quartz and feldspar indicate a terrigenous input,and pyrite suggests dysphotic to anaerobic conditions on the basin floor. Much of the skeletal material has likely been derived from a neighbouring shelf.

Age: The Lucan Formation ranges in age from Arundian to Asbian. In GSI-07-01 a suite of archaediscid foraminifers of Arundian age (MFZ 11) was recorded includingParaarchaediscusatinvolutusstage,PlanoarchaediscusandUralodiscus. In GSI-07-03 foraminifers of Asbian age(MFZ 13-14) are recorded, characterized by small archaediscids ofParaarchaediscusatangulatusstage.

3 Evolution of the depositional setting of Mississippian limestones in western Ireland

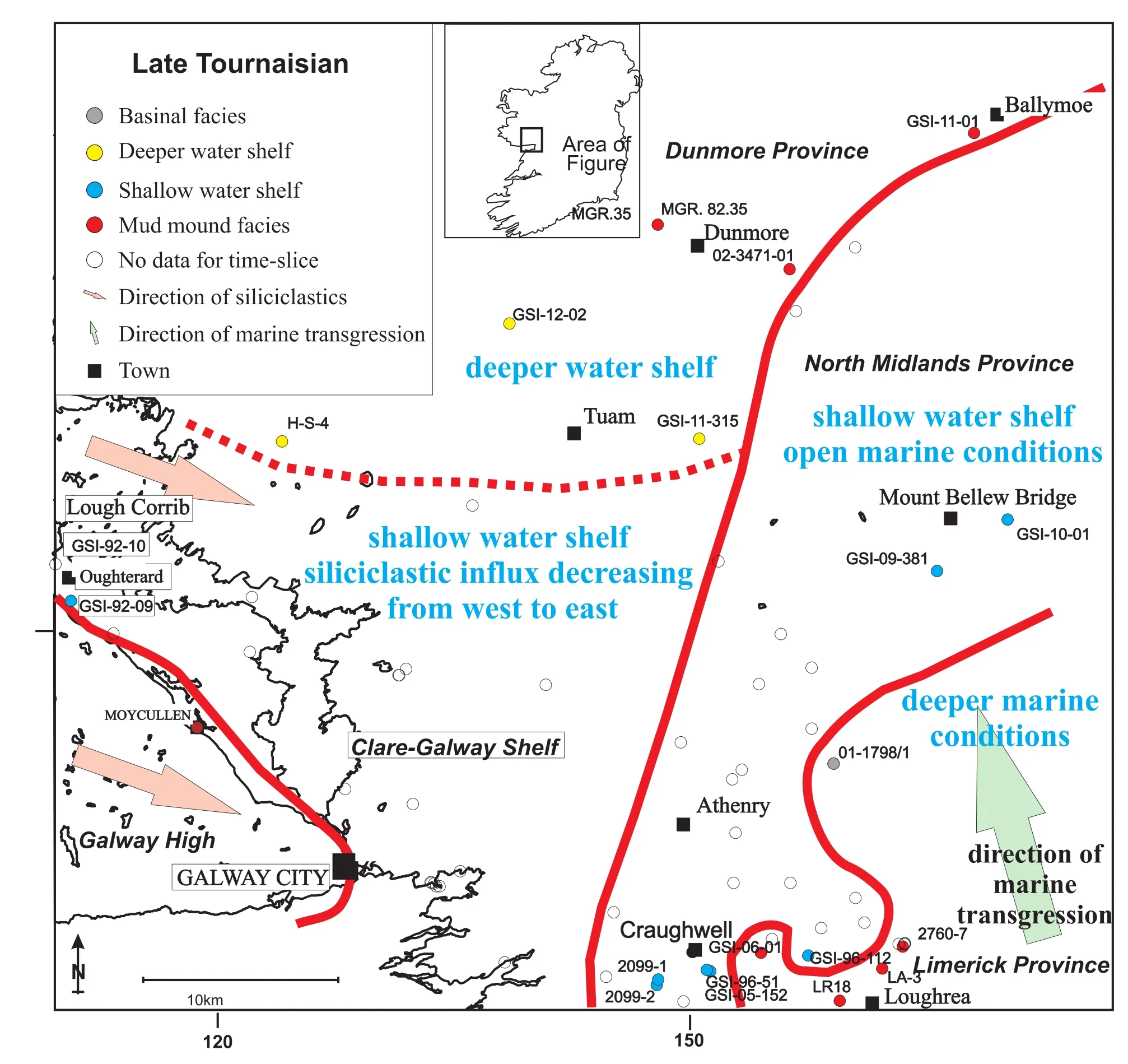

The oldest Mississippian marine rocks in the study area are known from boreholes in southern Co. Galway, the Burren and Loughrea in southeastern Galway. The Gort Borehole (G-1) and boreholes around Loughrea contain a transitional succession of sandstone, limestone and shale(Lower Limestone Shale Group) identified as belonging to the Limerick Province — a province recognized throughout most of Munster (Philcox, 1984; Somerville and Jones, 1985; Sleeman and Pracht, 1999). It marks a marine transgression which advanced northwards across the region during the Courceyan (Prachtet al.,2004; Sevastopulo and Wyse Jackson, 2009; Somerville and Waters,2011; Somervilleet al.,2011). The succeeding Ballysteen Formation represents widespread, uniform, limestone sedimentation with a rich and diverse open-marine fauna in the late Tournaisian, that developed as far north as Ballymoe (Figure 2). The area around Dunmore was designated by Philcox (1984) as a separate Tournaisian province(Dunmore Province), distinct from the Limerick Province to the south, but similar to the North Midlands Province to the east (Figure 10), although forming a much thinner succession.

The Ballysteen Formation is followed in the later Tournaisian by localized development of deeper water Waulsortian mud-mounds, which typically can be around 200-300 m thick in local complexes, surrounded by bedded cherty limestone (Lees, 1964, 1994; Lees and Miller, 1985, 1995;Devuyst and Lees, 2001; Somerville, 2003). However,in the Ballinasloe area in eastern Galway (Figure 1), the complexes amalgamated to form an interval >700 m thick(Gatleyet al.,2005). In the north of the region, around the Slieve Dart Inlier and Mount Bellew Bridge (Figure 2),thinner developments of Waulsortian mud-mound facies occur (Morriset al.,2003). These interfinger with rocks of the Kilbryan Limestone Formation. The latter formation is characterized by the presence of thin decomposed volcanic ash bands (tuffs) which form regional isochronous marker horizons between boreholes. In western Galway,around Lough Corrib, the laterally equivalent Oughterard Limestone Formation contains much siliciclastic detritus derived from the local basal clastics and the exposed Oughterard granite. It also contains a tuff band which may correlate with one in the Kilbryan Limestone Formation farther east. Microfossil data in the Oughterard Limestone suggest that the tuff band lies close to the chronostratigraphic Tournaisian-Viséan boundary (Sevastopulo and Wyse Jackson, 2009).

In the early Viséan (Chadian) there was the initiation of shallow-water platform sedimentation with bioclastic limestones, oolites and fenestral limestones (Oakport Limestone Formation). This was followed in the Arundian by more argillaceous bioclastic limestones rich in crinoids and fenestellid bryozoans with abundant colonies ofSiphonodendron(Ballymore Limestone Formation).Further to the south, bioclastic limestones of the laterally equivalent Tubber Formation developed, which have occasional oolitic grainstone intervals. In the southeast of the region, deep-water basinal facies were deposited (Lucan Formation) and over 700 m of mainly fine-grained,spiculitic, laminated limestone and mudstone, devoid of algae, accumulated during the Arundian to Asbian. East of Athenry there are rapid changes in thickness and facies changes recorded in the boreholes to suggest that syn-sedimentary faulting on the NE-trending Athenry Fault and ENE-trending Craughwell Fault (Figure 1) was probably partly controlling carbonate sedimentation (Figure 5).

Shallow-water limestone sedimentation continued over most of the region (Croghan Limestone and Tubber Limestone Formations) during the Holkerian, and in the Asbian,a uniform carbonate facies up to 400 m thick was developed throughout much of the region (Burren Formation).It is characterized by rich faunal bands of brachiopods and corals and abundant dasycladacean green alage. Most coral colonies are in situ but some are overturned. Many horizons of brachiopod contain concentrations of overturnedGigantoproductusimplying periodic strong storm currents sweeping across the shallow water shelf. The upper part of the formation (Two Mile Ditch Member) is also distinctive, as it contains clay wayboards, interpreted as palaeosols, which rest on irregular limestone surfaces considered to be palaeokarsts and comparable to those well-exposed in the Burren region in the Aillwee Member (Prachtet al.,2004; Gallagheret al.,2006). This unit shows a glacioeustatically controlled shallowing-upward cyclicity leading to subaerial emergence and karstification of exposed limestones, with terrestrial accumulation of soils. These features are typical of many late Asbian successions in southern Ireland (Gallagher, 1996; Gallagher and Somerville, 1997, 2003; Cózar and Somerville, 2005; Waterset al., 2011). Locally, the Burren Formation contains mud-mounds, over 35 m thick, which are only recognized in boreholes. They are like the older, larger Waulsortian mudmounds, which contain cavities with peloidal mud and radiaxial fibrous marine cements. However, locally, the Asbian mounds contain a boundstone framework provided by bryozoans. These are similar to bryozoan-rich mounds(buildups) described from coeval rocks in North Wales(Bancroftet al.,1988; Wyse Jacksonet al.,1991) in which the trepostomeLeioclemaandTabuliporawere important framework components of the buildup. Nevertheless, the absence of light-requiring algae and a sparse foraminiferal content suggest a quieter and probably deeper water shelf setting than most limestones of the Burren Formation.

The youngest Mississipian limestone rocks exposed in the Burren type section (Slievenaglasha Formation of Brigantian age) are not developed in the Galway area, and if ever deposited were subsequently eroded.

4 Palaeogeographic reconstructions

4.1 Tournaisian

The Lower Paleozoic and Precambrian rocks which lie to the west and northwest of Galway city would have formed a prominent high (Galway High) during the early Tournaisian, with lowland continental sedimentation occuring in the Oughterard area (Copeet al.,1992; Figure 10). This facies is recognized in boreholes, where red-bed sediments rest unconformably on the Oughterard granite.The Oughterard area forms part of the Connemara Massif(Figure 1), which was the source of much of the siliciclastic detritus brought into the west of the region, although its contribution diminished east of Lough Corrib (Figure 10).In the southeast of the region, however, marine sedimentation occurred, associated with a trangression that moved northwards across Co. Galway during the early Tournaisian (Ivorian) (Sevastopulo and Wyse Jackson, 2009; Figure 10).

The transitional limestone, shale and sandstone succession of the Lower Limestone Shale Group, comprises cross-bedded sandstones, oolitic and skeletal grainstones and mudstones with desiccation cracks (Somerville and Jones, 1985). These indicate an alternation of intervals of sedimentation during low- and high-energy conditions with periodic exposure. They represent a marginal marine to shallow-water open shelf succession that developed on the Clare-Galway Shelf which extended south into the Limerick Province (Sevastopulo and Wyse Jackson,2009). It was succeeded by a predominantly limestonerich deeper water shelf succession of the Ballysteen Group(Somerville and Waters, 2011). The latter, including the Ballymartin and Ballysteen Formations, represents more open-marine conditions with a richer and more diverse fauna. It is recognized as far north as the Dunmore-Ballymoe area. In the late Tournaisian, the deepest water facies was developed in the Loughrea area in the southeast (Figure 10), where thick accumulations of Waulsortian Limestone are recorded (Lees and Miller, 1995). These would have formed prominent mud-mounds with substantial topographic sea-floor relief of several hundred metres, most of which was below the photic zone, as dasycladacean algae are absent (Lees and Miller, 1995; Somerville, 2003).Low-energy sedimentation continued, in part coevally,with the deposition of the Kilbryan Limestone Formation in the northern part of the region, although probably in shallower water, with an abundance of sponge spicules,fenestellid bryozoans and ostracods, with occasional corals. This formation is also characterized by rare thin green clay bands considered to be decomposed volcanic ash bands (tuffs), which can act as isochronous surfaces. Similar horizons are recorded in the Oughterard Limestone in the west and the equivalent Argillaceous Limestone in Co.Longford, east of the River Shannon (Morriset al.,2003),marking a distinct episode of volcanicity throughout central Ireland in the latest Tournaisian.

4.2 Early-Middle Viséan

In the early Viséan (Chadian), a marked shallowing event occurred which led to the development of a widespread shallow-water platform in the northern part of the region. This was the initiation of the Galway-Roscommon Shelf (Figure 11), which is known to extend as far north as Boyle and Carrick-on-Shannon (Morriset al.,2003;Sevastopulo and Wyse Jackson, 2009; Figure 1). It represents the accumulation of high-energy bioclastic and oolitic grainstones rich in dasycladacean algae, alternating with low-energy lagoonal fenestral micrites of the Oakport Limestone Formation. In the Arundian, slightly deeper water shelf facies developed (Ballymore Limestone Formation) with more argillaceous bioclastic limestones and coral biostromes. This facies is known throughout the northern part of Co. Galway, but is laterally equivalent to the more variable Tubber Formation, which is known from the Craughwell area in the south and contains oolites, developed on the Clare-Galway Shelf (Figure 11). In the east of the region, east of Athenry, deep-water basinal conditions are recorded with the deposition of the Lucan Formation in the Athenry Basin (Figure 11). This facies is known to extend farther east and probably forms the western margin of the Tynagh Basin (Sevastopulo and Wyse Jackson,2009) which lies south of Ballinasloe (Gatleyet al.,2005;Figure 1). The initiation of these subsiding basins in the early Viséan (Chadian) where substantial thicknesses of sediment accumulated, was probably related to a phase of extensional tectonics which is known throughout the region (e.g.Tynagh; Philcox, 1984) and the Curlew Fault,north of the Curlew Mountains (Figure 1; Philcox, 1989;Philcoxet al., 1992), and eastwards into the Dublin Basin(Nolan, 1989; Strogenet al.,1996).

Figure 10 Palaeogeographic reconstruction of Co. Galway region for the late Tournaisian (based on Cope et al., 1992).

4.3 Late Viséan

In the late Viséan, shallow-water shelf facies is welldeveloped in the south and southwest of the region with the deposition of the Burren Formation on the Clare-Galway Shelf (Figures 1, 11). This limestone facies has a rich and diverse fauna and flora with abundant foraminifers and red and green algae. Coral biostromes are also well developed,as well as concentrations of large brachiopod bands. The presence of palaeokarstic surfaces and overlying palaeosols is an indication of periodic subaerial exposure of the carbonates. A similar shallow-water carbonate shelf is developed in the northeast of the region near Mount Bellew Bridge. However, the two shelves are separated by deeper water basinal facies of the Athenry Basin marking a continuation of the Lucan Formation (Figure 11). In some instances, though, there is clear evidence in long borehole sections (GSI-06-387, GSI-06-02) to demonstrate that the two facies interfinger.

Figure 11 Palaeogeographic reconstruction of Co. Galway region for the Viséan (Chadian-Asbian) (based on Cope et al., 1992).

South of Galway City and around Lough Corrib, rare bryozoan-rich mud-mounds occur within the bedded limestones of the Burren Formation (Figure 11). These buildups probably represent a slightly deeper water shelf setting but are surrounded by algal-rich bioclastic limestones that clearly formed in shallow water. These mounds are similar to the Waulsortian-type mounds in possessing stromatactis cavities with radiaxial fibrous marine cements, that are known west of Lough Ree at Lecarrow (30 km northeast of Mount Bellew Bridge) (Morriset al.,2003) close to the northwestern margin of the Dublin Basin between Athenry, Ballinasloe and Athlone (Figure 1). They are also similar to the Asbian mounds of Co. Sligo (Somerville, 2003;Somervilleet al.,2009). They have affinity with shelf margin mounds described from the northern margin of the Dublin Basin near Loughshinny (Somervilleet al.,1992;Somerville, 2003) which have locally developed boundstone frameworks.

5 Conclusions

1) Analysis of new borehole data integrated with older borehole records and combined with outcrop study has enabled a more detailed comprehensive geological map and lithostratigraphy to be constructed for the Mississippian rocks of Co. Galway in western Ireland.

2) Micropalaeontological investigations using foraminifers and microfacies analysis of the limestones has enabled them to be precisely dated and their components,textures and fabrics documented. In addition, palaeogeographic map reconstructions have been achieved for the late Tournaisian, and early to late Viséan intervals in the region.

3) In the southeast of the region the oldest marine Mississippian deposits are associated with a transgression that moved northwards across Co. Galway. These Tournaisian rocks belong to the Limerick Province, and are represented by the Lower Limestone Shale and Ballysteen Groups followed by Waulsortian Limestone Formation, as part of an overall deepening-upward trend. In the northwest and north of the region, marine Tournaisian rocks are much thinner with a shoreline located northwest of Galway City (Galway High).

4) The central region of Co. Galway has a standard Viséan succession that can be directly correlated with the Carrick-on-Shannon succession in counties Roscommon and Leitrim to the northeast and east as far as the River Shannon. It is dominated by shallow-water limestones(Oakport, Ballymore and Croghan Limestone Formations)that formed the Galway-Roscommon Shelf. This succession is laterally equivalent to the Tubber Formation to the south. In the southeast of the region basinal facies of the Lucan Formation accumulated in the Athenry Basin, which was probably connected to the Tynagh Basin to the east(Figure 1) and persisted throughout most of the Viséan.

5) In the late Viséan, shallow-water limestones of the Burren Formation extended across much of the southern part of the region on the Clare-Galway Shelf. These limestones exhibit distinctive palaeokarstic surfaces overlain by terrestrial accumulations of palaeosols which formed during prolonged regressive conditions of glacio-eustatically controlled cyclicity. They also are characterized by the presence of rich concentrations of large brachiopod shells and colonial coral horizons which developed in predominantly high-energy conditions, along with abundant foraminifers and calcareous algae. Locally, bryozoan-rich mud-mounds developed in slightly deeper water, lower energy conditions on the shelf.

Acknowledgements

Markus Pracht publishes with permission provided by the Director of the Geological Survey of Ireland. Brian McConnell is thanked for his insightful comments on an earlier draft of the paper. The reviewers Markus Aretz,Tadeusz Peryt and Colin Waters, and the Editor-in-Chief,Prof. Zeng-Zhao Feng are thanked for their constructive comments which helped improve the final version.

Journal of Palaeogeography2015年1期

Journal of Palaeogeography2015年1期

- Journal of Palaeogeography的其它文章

- Provenance and drainage system of the Early Cretaceous volcanic detritus in the Himalaya as constrained by detrital zircon geochronology

- 3D palaeogeographic reconstructions of the Phanerozoic versus sea-level and Sr-ratio variations

- Modern Black Sea oceanography applied to the end-Permian extinction event

- Nonmarine time-stratigraphy in a rift setting: An example from the Mid-Permian lower Quanzijie low-order cycle, Bogda Mountains, NW China

- General regulations about submitting manuscripts to Journal of Palaeogeography

- 2nd International Palaeogeography Conference October 10?13, 2015